Repair and Reverse-Engineering of Nespresso Vertuo Next Coffee Machines

Akin to the razor-and-blades model, capsule-based coffee machines are an endless grind of overpriced pods and cheaply made machines that you’re supposed to throw out and buy a new one of, just so that you don’t waste all the proprietary pods you still have at home. What this also means is a seemingly endless supply of free broken capsule coffee makers that might be repairable. This is roughly how [Mark Furneaux] got into the habit of obtaining various Nespresso VertuoLine machines for attempted repairs.

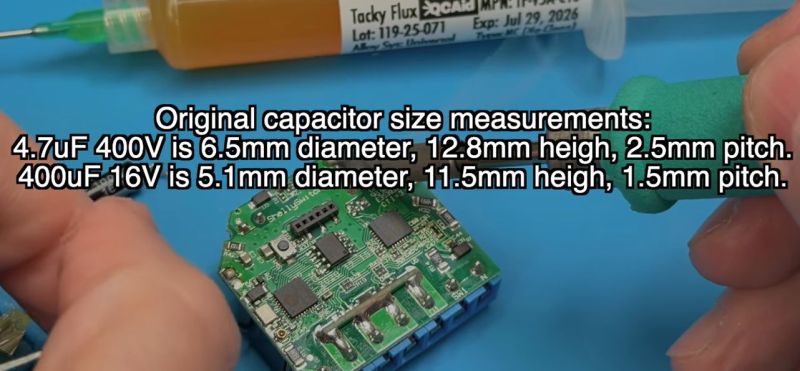

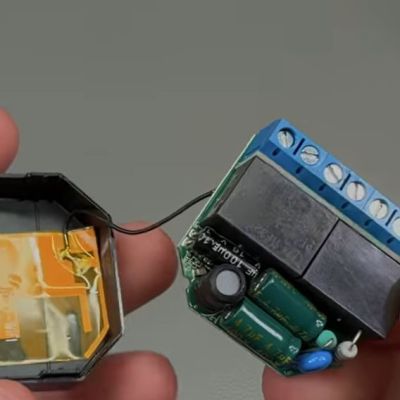

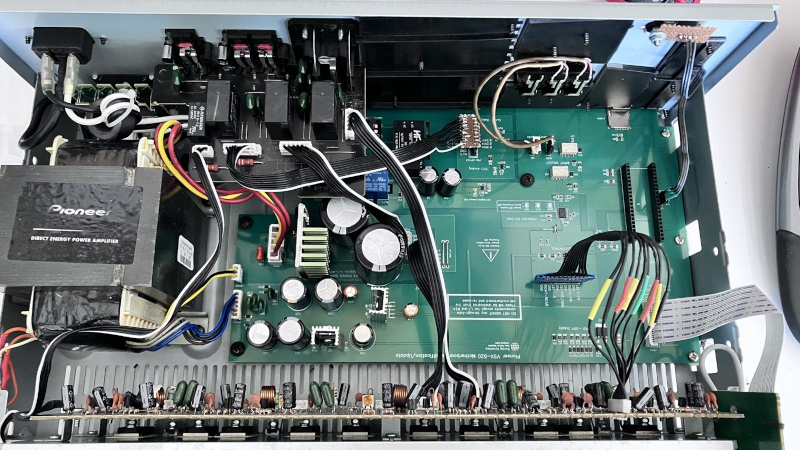

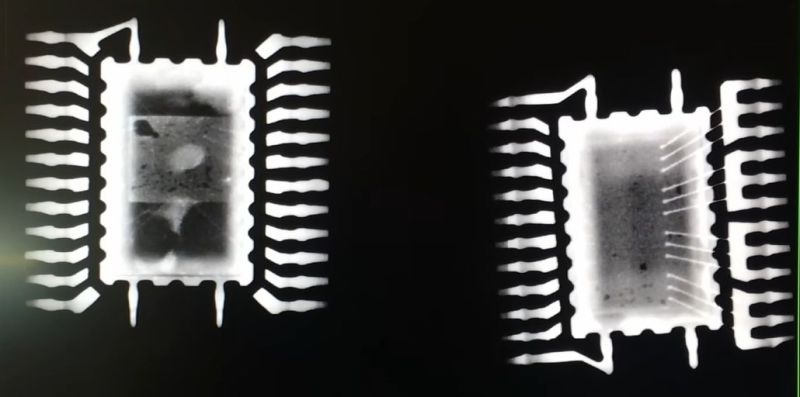

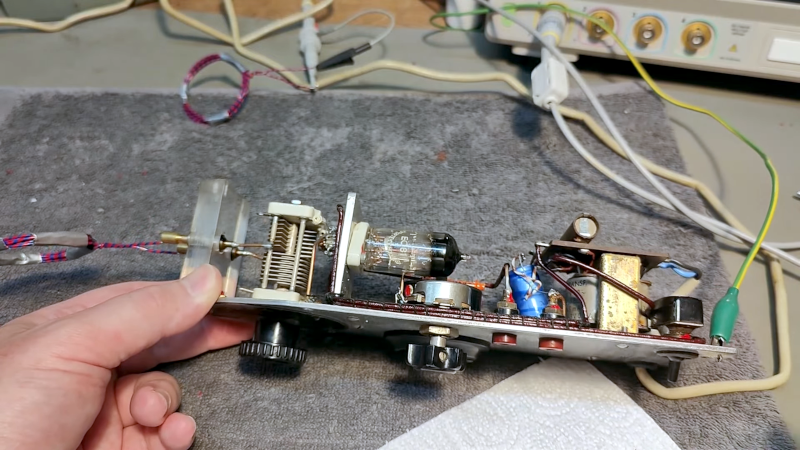

The VirtuoLine machines feature the capsule with a bar code printed on the bottom of the lip, requiring the capsule to be spun around so that it can be read by the optical reader. Upon successful reading, the code is passed to the MCU after which the brewing process is either commenced or cruelly halted if the code fails. Two of the Vertuo Next machines that [Mark] got had such capsule reading errors, leading to a full teardown of the first after the scanner board turned out to work fine.

Long story short and many hours of scrubbed footage later, one machine was apparently missing the lens assembly on top of the photo diode and IR LED, while the other simply had these lenses gunked up with spilled coffee. Of course, getting to this lens assembly still required a full machine teardown, making cleaning it an arduous task.

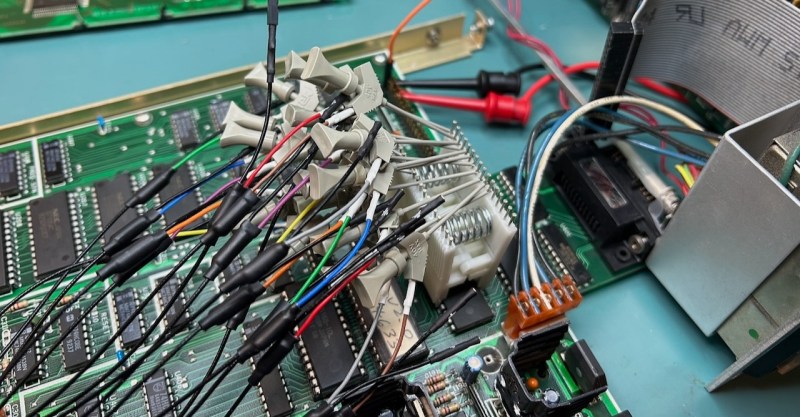

Unfortunately the machine that had the missing lens assembly turned out to have another fault which even after hours of debugging remained elusive, but at least there was one working coffee machine afterwards to make a cup of joe to make [Mark] feel slightly better about his life choices. As for why the lens assembly was missing, it’s quite possible that someone else tried to repair the original fault, didn’t find it, and reassembled the machine without the lens before passing the problem on to the next victim.