Skimming Satellites: On the Edge of the Atmosphere

There’s little about building spacecraft that anyone would call simple. But there’s at least one element of designing a vehicle that will operate outside the Earth’s atmosphere that’s fairly easier to handle: aerodynamics. That’s because, at the altitude that most satellites operate at, drag can essentially be ignored. Which is why most satellites look like refrigerators with solar panels and high-gain antennas attached jutting out at odd angles.

But for all the advantages that the lack of meaningful drag on a vehicle has, there’s at least one big potential downside. If a spacecraft is orbiting high enough over the Earth that the impact of atmospheric drag is negligible, then the only way that vehicle is coming back down in a reasonable amount of time is if it has the means to reduce its own velocity. Otherwise, it could be stuck in orbit for decades. At a high enough orbit, it could essentially stay up forever.

There was a time when that kind of thing wasn’t a problem. It was just enough to get into space in the first place, and little thought was given to what was going to happen in five or ten years down the road. But today, low Earth orbit is getting crowded. As the cost of launching something into space continues to drop, multiple companies are either planning or actively building their own satellite constellations comprised of thousands of individual spacecraft.

Fortunately, there may be a simple solution to this problem. By putting a satellite into what’s known as a very low Earth orbit (VLEO), a spacecraft will experience enough drag that maintaining its velocity requires constantly firing its thrusters. Naturally this presents its own technical challenges, but the upside is that such an orbit is essentially self-cleaning — should the craft’s propulsion fail, it would fall out of orbit and burn up in months or even weeks. As an added bonus, operating at a lower altitude has other practical advantages, such as allowing for lower latency communication.

VLEO satellites hold considerable promise, but successfully operating in this unique environment requires certain design considerations. The result are vehicles that look less like the flying refrigerators we’re used to, with a hybrid design that features the sort of aerodynamic considerations more commonly found on aircraft.

ESA’s Pioneering Work

This might sound like science fiction, but such craft have already been developed and successfully operated in VLEO. The best example so far is the Gravity Field and Steady-State Ocean Circulation Explorer (GOCE), launched by the European Space Agency (ESA) back in 2009.

To make its observations, GOCE operated at an altitude of 255 kilometers (158 miles), and dropped as low as just 229 km (142 mi) in the final phases of the mission. For reference the International Space Station flies at around 400 km (250 mi), and the innermost “shell” of SpaceX’s Starlink satellites are currently being moved to 480 km (298 mi).

Given the considerable drag experienced by GOCE at these altitudes, the spacecraft bore little resemblance to a traditional satellite. Rather than putting the solar panels on outstretched “wings”, they were mounted to the surface of the dart-like vehicle. To keep its orientation relative to the Earth’s surface stable, the craft featured stubby tail fins that made it look like a futuristic torpedo.

Given the considerable drag experienced by GOCE at these altitudes, the spacecraft bore little resemblance to a traditional satellite. Rather than putting the solar panels on outstretched “wings”, they were mounted to the surface of the dart-like vehicle. To keep its orientation relative to the Earth’s surface stable, the craft featured stubby tail fins that made it look like a futuristic torpedo.

Even with its streamlined design, maintaining such a low orbit required GOCE to continually fire its high-efficiency ion engine for the duration of its mission, which ended up being four and a half years.

In the case of GOCE, the end of the mission was dictated by how much propellant it carried. Once it had burned through the 40 kg (88 lb) of xenon onboard, the vehicle would begin to rapidly decelerate, and ground controllers estimated it would re-enter the atmosphere in a matter of weeks. Ultimately the engine officially shutdown on October 21st, and by November 9th, it’s orbit had already decayed to 155 km (96 mi). Two days later, the craft burned up in the atmosphere.

JAXA Lowers the Bar

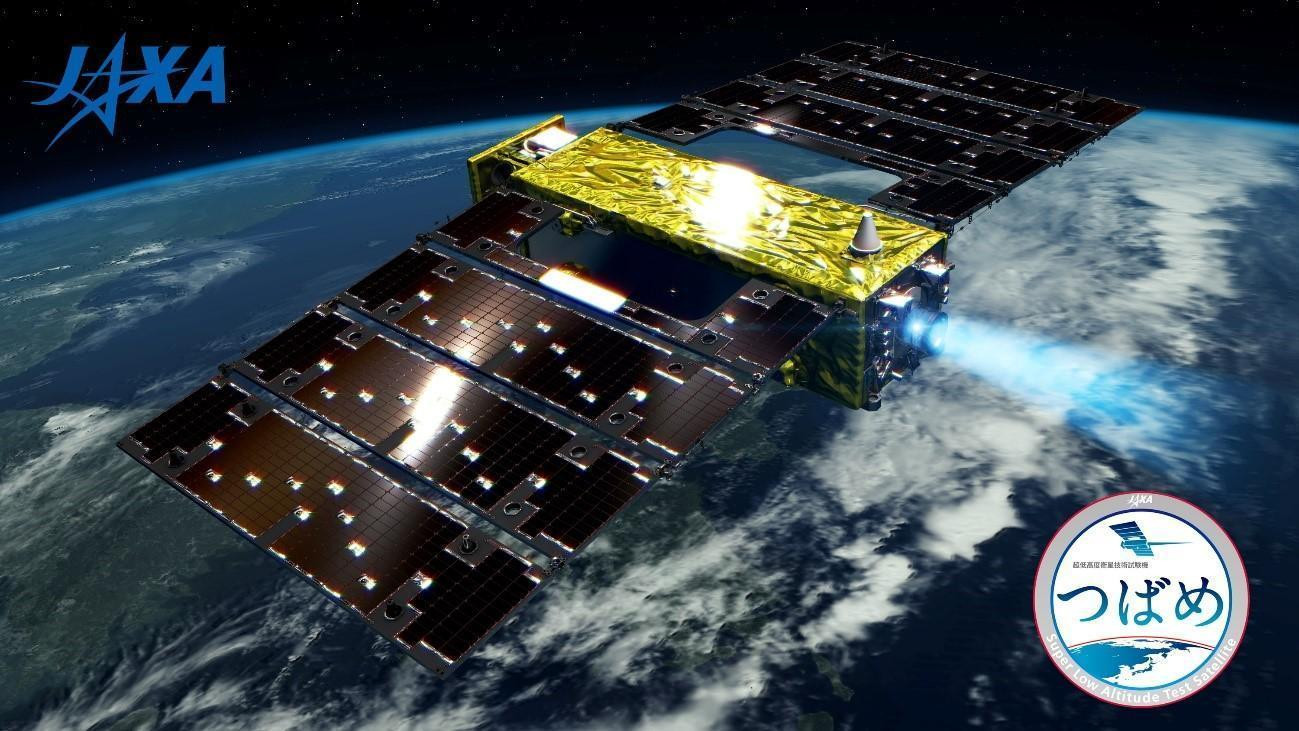

While GOCE may be the most significant VLEO mission so far from a scientific and engineering standpoint, the current record for the spacecraft with the lowest operational orbit is actually held by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA).

In December 2017 JAXA launched the Super Low Altitude Test Satellite (SLATS) into an initial orbit of 630 km (390 mi), which was steadily lowered in phases over the next several weeks until it reached 167.4 km (104 mi). Like GOCE, SLATS used a continuously operating ion engine to maintain velocity, although at the lowest altitudes, it also used chemical reaction control system (RCS) thrusters to counteract the higher drag.

SLATS was a much smaller vehicle than GOCE, coming in at roughly half the mass. It also carried just 12 kg (26 lb) of xenon propellant, which limited its operational life. It also utilized a far more conventional design than GOCE, although its rectangular shape was somewhat streamlined when compared to a traditional satellite. Its solar arrays were also mounted in parallel to the main body of the craft, giving it an airplane-like appearance.

The combination of lower altitude and higher frontal drag meant that SLATS had an even harder time maintaining velocity than GOCE. Once its propulsion system was finally switched off in October 2019, the craft re-entered the atmosphere and burned up within 24 hours. The mission has since been recognized by Guinness World Records for the lowest altitude maintained by an Earth observation satellite.

A New Breed of Satellite

As impressive as GOCE and SLATS were, their success was based more on careful planning than any particular technological breakthrough. After all, ion propulsion for satellites is not new, nor is the field of aerodynamics. The concepts were simply applied in a novel way.

But there exists the potential for a totally new type of vehicle that operates exclusively in VLEO. Such a craft would be a true hybrid, in the sense that its primarily a spacecraft, but uses an air-breathing electric propulsion (ABEP) system akin to an aircraft’s jet engine. Such a vehicle could, at least in theory, maintain an altitude as low as 90 km (56 mi) indefinitely — so long as its solar panels can produce enough power.

But there exists the potential for a totally new type of vehicle that operates exclusively in VLEO. Such a craft would be a true hybrid, in the sense that its primarily a spacecraft, but uses an air-breathing electric propulsion (ABEP) system akin to an aircraft’s jet engine. Such a vehicle could, at least in theory, maintain an altitude as low as 90 km (56 mi) indefinitely — so long as its solar panels can produce enough power.

Both the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in the United States and the ESA are currently funding several studies of ABEP vehicles, such as Redwire’s SabreSat, which have numerous military and civilian applications. Test flights are still years away, but should VLEO satellites powered by ABEP become common platforms for constellation applications, they may help alleviate orbital congestion before it becomes a serious enough problem to impact our utilization of space.