As the U.S. looks to bolster electric vehicle (EV) adoption, a new challenge is on the horizon: cybersecurity.

Given the interconnected nature of these vehicles and their reliance on local power grids, they’re not just an alternative option for getting from Point A to Point B. They also offer a new path for network compromise that could put drivers, companies and infrastructure at risk.

To help address this issue, the Office of the National Cyber Director (ONCD) recently hosted a forum with both government leaders and private companies to assess both current and emerging EV threats. While the discussion didn’t delve into creating cybersecurity standards for these vehicles, it highlights the growing need for EV roadmaps that help reduce cyber risk.

Lighting Strikes? The State of Electric Adoption

EV sales in the United States are well ahead of expert predictions. Just five years ago, fully electric vehicles were considered niche. A great idea in theory, but lacking the functionality and reliability afforded by traditional combustion-based cars.

In 2022, however, the tide is turning. According to InsideEVs, demand now outpaces the supply of electric vehicles across the United States. With a new set of tax credits available, this demand isn’t going anywhere but up, even as manufacturers struggle to improve the pace of production.

Part of this growing interest stems from the technology itself. Battery life increases as charging times fall, and the EV market continues to diversify. While first-generation electric vehicle makers like Tesla continue to report strong sales, the offerings of more mainstream brands like Ford, Mazda and Nissan have helped spur consumer interest.

The result? The United States has now passed a critical milestone in EV sales: 5% of new cars sold are entirely electric. If the sales patterns stateside follow that of 18 other countries that have reached this mark, EVs could account for 25% of all cars sold in the country by 2025, years ahead of current forecasts.

Positive and Negative — Potential EV Issues

While EV adoption is good for vehicle manufacturers and can ease reliance on fossil fuels, cybersecurity remains a concern.

Consider that in early 2022, 19-year-old security researcher David Colombo was able to hack into 25 Teslas around the world using a third-party, open-source logging tool known as Teslamate. According to Colombo, he was able to lock and unlock doors and windows, turn on the stereo, honk the horn and view the car’s location. While he didn’t believe it was possible to take over and drive the car remotely, the compromise nonetheless showed significant vulnerability at the point where OEM technology overlaps third-party offerings. Colombo didn’t share his data immediately; instead, he contacted TelsaMate and waited until the issue was addressed. Malicious actors, meanwhile, share no such moral code and could leverage this kind of weakness to extort EV owners.

And this is just the beginning. Other possible cyber threat avenues include:

Connected vehicle systems

EV systems such as navigation and optimal route planning rely on WiFi and cellular networks to provide real-time updates. If attackers can compromise these networks, however, they may be able to access key systems and put drivers at risk. For example, if malicious actors gain control of the vehicle’s primary operating system, they could potentially disable key safety features or lock drivers out of critical commands.

Charging stations

Along with providing power to electric vehicles, charging stations may also record information about vehicle charge rates, identification numbers and information tied to drivers’ EV application profiles. As a result, vulnerable charging stations offer a potential path to exfiltrated data that could compromise driver accounts.

Local power grids

With public charging stations using local power grids to deliver fast charging when drivers aren’t at home, attackers could take aim at lateral moves to infect car systems with advanced persistent threats (APTs) that lie in wait until cars are plugged in. Then, malicious code could travel back along power grid connections to compromise local utility providers.

Powering Up Protection

With mainstream EV adoption looming, it’s a matter of when, not if, a major cyberattack occurs. Efforts such as the ONCD forum are a great starting point for discussion about EV security standards. However, well-meaning efforts are no replacement for effective cybersecurity operations.

In practice, potential protections could take several forms.

First is the use of automated security solutions to manage user logins and access. By reducing the number of touchpoints for users, it’s possible to limit the overall attack surfaces that EV ecosystems create.

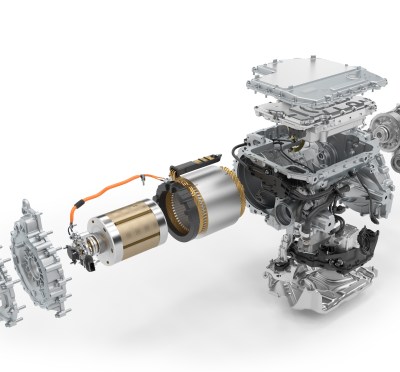

Next is the use of security by design. As noted by a recent Forbes piece, new vehicles are effectively “20 computers on wheels,” many of which are embedded in hardware systems. The result is the perfect setup for firmware failures if OEMs don’t take the time to make basic security protocols — such as usernames and passwords that aren’t simply “admin” and “password”, and the use of encrypted data — part of each EV computer.

Finally, there’s a need for transparency across all aspects of EV supply, design, development and construction. Given the sheer number of components in electric vehicles which represent a potential failure point, end-to-end visibility is critical for OEMs to ensure that top-level security measures are supported by all EV hardware and software components.

Getting from Here to There

As EVs become commonplace, a cybersecurity roadmap is critical to keep these cars on the road up to operator — and operational — safety standards.

But getting from here to there won’t happen overnight. Instead, this mapping mission requires the combined efforts of government agencies, EV OEMs and vehicle owners to help maximize automotive protection.

The post Defensive Driving: The Need for EV Cybersecurity Roadmaps appeared first on Security Intelligence.