NASA Confident, But Some Critics Wonder if Its Orion Spacecraft is Safe to Fly

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

After moving the massive SLS rocket and Orion spacecraft to the launchpad last weekend, NASA is now eyeing the next stage of its preparations for Artemis II, the first crewed lunar mission in more than five decades. Now firmly in place at Launch Pad 39B at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, the rocket will […]

The post Key moment approaches for NASA’s crewed moon mission appeared first on Digital Trends.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

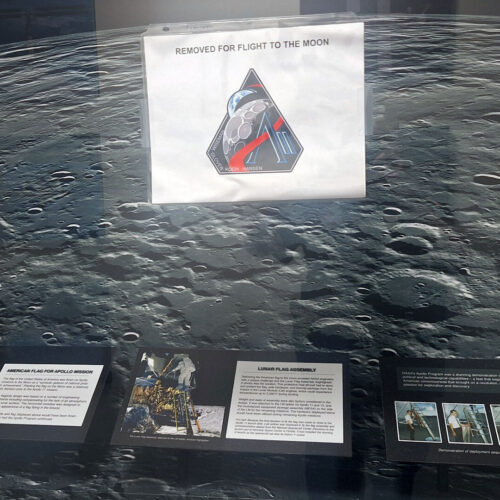

NASA's first astronauts to fly to the Moon in more than 50 years will pay tribute to the lunar and space exploration missions that preceded them, as well as aviation and American history, by taking with them artifacts and mementos representing those past accomplishments.

NASA, on Wednesday, January 21, revealed the contents of the Artemis II mission's Official Flight Kit (OFK), continuing a tradition dating back to the Apollo program of packing a duffel bag-sized pouch of symbolic and celebratory items to commemorate the flight and recognize the people behind it. The kit includes more than 2,300 items, including a handful of relics.

"This mission will bring together pieces of our earliest achievements in aviation, defining moments from human spaceflight and symbols of where we're headed next," Jared Isaacman, NASA's administrator, said in a statement. "Historical artifacts flying aboard Artemis II reflect the long arc of American exploration and the generations of innovators who made this moment possible."

© Cole Simmons via collectSPACE.com

The excitement is building as NASA works toward launching its first crewed lunar flight in more than five decades. The Artemis II mission, which will take four astronauts on a 10-day voyage around the moon, could lift off as early as February 6. NASA has just released a cinematic trailer for the highly anticipated mission. […]

The post NASA shares thrilling sneak peek at humanity’s imminent return to the moon appeared first on Digital Trends.

Nearly 14 years ago, NASA’s Curiosity rover landed on Mars for a mission to explore the red planet and discover if it had an environment capable of supporting microbial life. Over the years, the rover has also been beaming back striking images of its surroundings, including the stunner at the top of this page captured […]

The post Mars has never looked so serene in this gorgeous image from a NASA rover appeared first on Digital Trends.

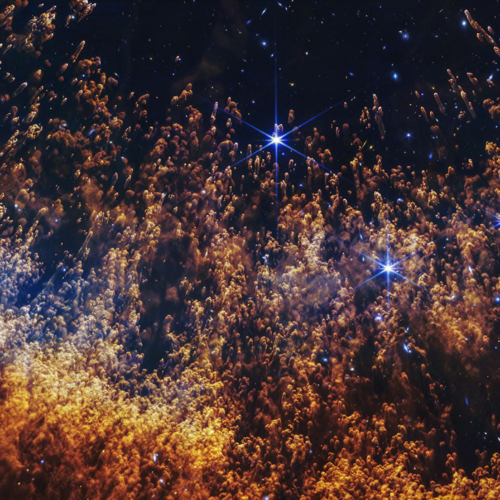

The Helix Nebula is one of the most well-known and commonly photographed planetary nebulae because it resembles the "Eye of Sauron." It is also one of the closest bright nebulae to Earth, located approximately 655 light-years from our Solar System.

You may not know what this particular nebula looks like when reading its name, but the Hubble Space Telescope has taken some iconic images of it over the years. And almost certainly, you'll recognize a photograph of the Helix Nebula, shown below.

Like many objects in astronomy, planetary nebulae have a confusing name, since they are formed not by planets but by stars like our own Sun, though a little larger. Near the end of their lives, these stars shed large amounts of gas in an expanding shell that, however briefly in cosmological time, put on a grand show.

© ASA, ESA, CSA, STScI; Image Processing: Alyssa Pagan (STScI)

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, Florida—Preparations for the first human spaceflight to the Moon in more than 50 years took a big step forward this weekend with the rollout of the Artemis II rocket to its launch pad.

The rocket reached a top speed of just 1 mph on the four-mile, 12-hour journey from the Vehicle Assembly Building to Launch Complex 39B at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. At the end of its nearly 10-day tour through cislunar space, the Orion capsule on top of the rocket will exceed 25,000 mph as it plunges into the atmosphere to bring its four-person crew back to Earth.

"This is the start of a very long journey," said NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman. "We ended our last human exploration of the moon on Apollo 17."

© Stephen Clark/Ars Technica

The Internet has spoiled us. You assume network packets either show up pretty quickly or they are never going to show up. Even if you are using WiFi in a crowded sports stadium or LTE on the side of a deserted highway, you probably either have no connection or a fairly robust, although perhaps intermittent, network. But it hasn’t always been that way. Radio networks, especially, used to be very hit or miss and, in some cases, still are.

Perhaps the least reliable network today is one connecting things in deep space. That’s why NASA has a keen interest in Delay Tolerant Networking (DTN). Note that this is the name of a protocol, not just a wish for a certain quality in your network. DTN has been around a while, seen real use, and is available for you to use, too.

Think about it. On Earth, a long ping time might be 400 ms, and most of that is in equipment, not physical distance. Add a geostationary orbital relay, and you get 600 ms to 800 ms. The moon? The delay is 1.3 sec. Mars? Somewhere between 3 min and 22 min, depending on how far away it is at the moment. Voyager 1? Nearly a two-day round trip. That’s latency!

So how do you network at these scales? NASA’s answer is DTN. It assumes the network will not be present, and when it is, it will be intermittent and slow to respond.

This is a big change from TCP. TCP assumes that if packets don’t show up, they are lost and does special algorithms to account for the usual cause of lost TCP packets: congestion. That means, typically, they wait longer and longer to retry. But if your packets are not going through because the receiver is behind a planet, this isn’t the right approach.

DTN nodes operate like a mesh. If you hear something, you may have to act as a relay point even if the message isn’t for you. Unlike most store-and-forward networks, though, a DTN node may store a message for hours or even days. Unlike most Earthbound network nodes, a DTN node may be moving. In fact, all of them might be moving. So you can’t depend on any given node being able to hear another node, even if they have heard each other in the past.

Is this new? Hardly. Email is store-and-forward, even if it doesn’t seem much like it these days. UUCP and Fidonet had the same basic ideas. If you are a ham radio operator with packet (AX.25) experience, you may see some similarities there, too. But DTN forms a modern and robust network for general purposes and not just a way to send particular types of messages or files.

While the underlying transport layer might use small packets — think TCP — DTN uses bundles, which are large self-contained messages with a good bit of metadata attached. Bundles don’t care if they move over TCP, UDP, or some wacky RF protocol. The metadata explains where the data is going, how urgent it is, and at what point you can just give up and discard it. The bundle’s header has other data, too, such as the length and whether the current bundle is just a fragment of a larger bundle. There are also flags forbidding the fragmentation of a bundle.

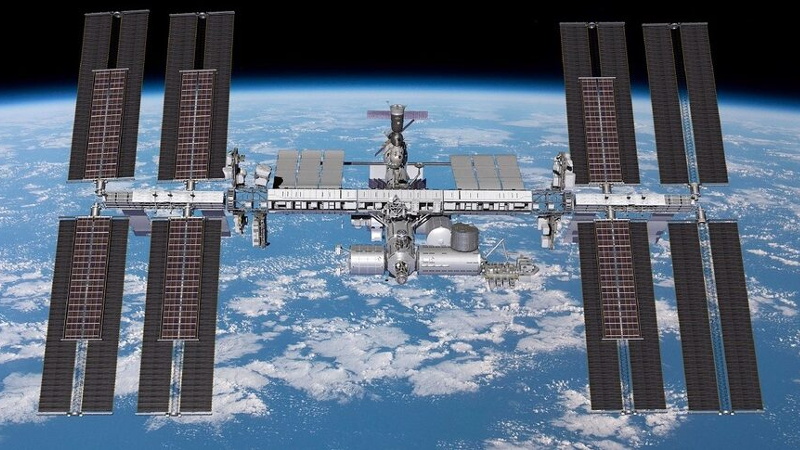

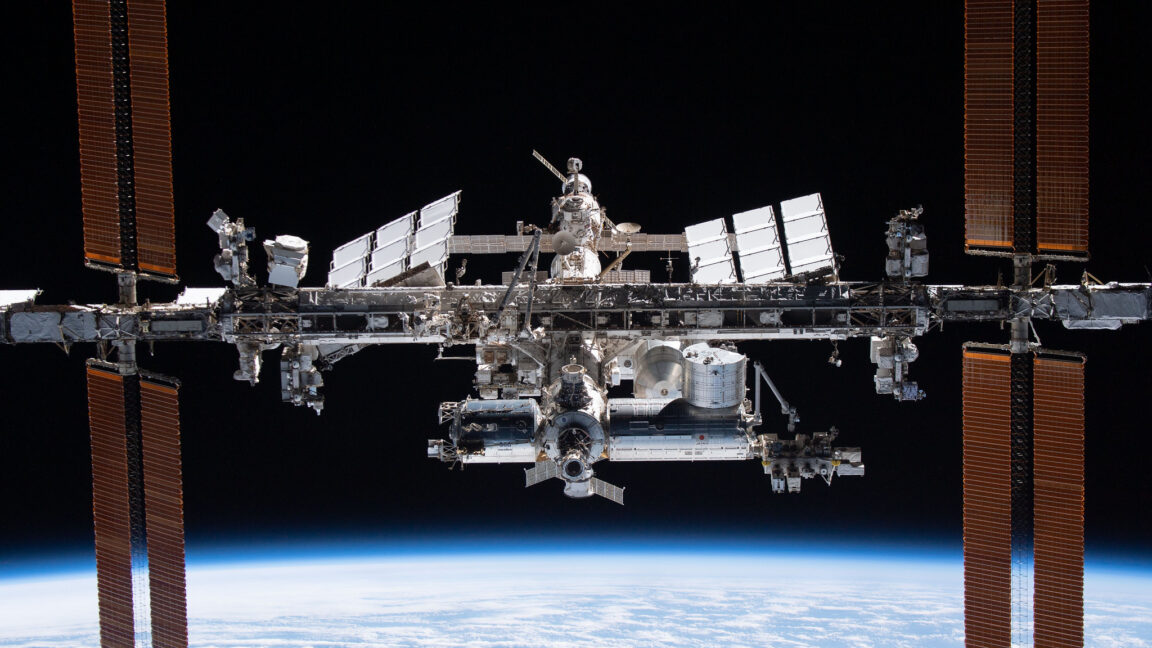

DTN isn’t just a theory. It has been used on the International Space Station and is likely to show up in future missions aimed at the moon and beyond.

But even better, DTN implementations exist and are available for anyone to use. NASA’s reference implementation is ION (Interplanetary Overlay Network), and it is made for NASA-level safety. It will, though, run on a Raspberry Pi. You can see a training video about ION and DTN in the video below.

There are some more community-minded implementations like DTN2 and DTN7. If you want to experiment, we’d suggest starting with DTN7. The video below can help you get started.

We hear you. As much as you might like to, you aren’t sending anything to Mars this week. But DTN is useful anywhere you have unreliable crummy networking. Disaster recovery? Low-power tracking transmitters that die until the sun hits their solar cells? Weak signal links in hostile terrain. All of these use cases could benefit from DTN.

We are always surprised that we don’t see more DTN in regular applications. It isn’t magic, and it doesn’t make radios defy the laws of physics. What it does is prevent your network from suffering fatally from those laws when the going gets tough.

Sure. You can do this all on your own. No NASA pun intended, but it isn’t rocket science. For specialized cases, you might even be able to do better. After all, UUCP dates back to the late 1970s and shares many of the same features. Remember UUCP schedules that determined when one machine would call another? DTN has contact plans that serve a similar purpose, except that instead of waiting for low long-distance rates, the contact plan is probably waiting for a predicted acquisition of signal time.

But otherwise? You knew UUCP wasn’t immediate. Routing decisions were often due to expectations of the future. Indefinite storage was all part of the system. Usenet, of course, rode on top of UUCP. So you could think of Usenet as almost a planetary-scale DTN network with messages instead of bundles.

A Usenet post might take days to show up at a remote site. It might arrive out of order, or twice. DTN has all of these same features. So while some would say DTN is the way of the future, at least in deep space networking, we would submit that DTN is a rediscovery of some very old techniques when networking on Earth was as tenuous as today’s space networks.

We’re sure that by modern standards, UUCP had some security flaws. DTN can suffer from some security issues, too. A rogue node can accept bundles and silently kill them, for example. Or flood the network with garbage bundles.

Then again, TCP DoS or man-in-the-middle attacks are possible, too. You simply have to be careful and think through what you are doing, if it is possible someone will attack your network.

So next time your project needs a rough-and-tumble network that survives even when you aren’t connected to the gigabit LAN, maybe try DTN. It has come a long way, literally and figuratively, since 2008. Well, actually, since 1997, as you can see in the video below. Whatever you come up with, be sure to send us a tip.

NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and Orion spacecraft reached the Launch Pad 39B at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Saturday following a 4-mile, 12-hour crawl from the Vehicle Assembly Building. The rocket is being prepped for the Artemis II mission, which will carry three Americans and one Canadian on a voyage around […]

The post NASA’s mega moon rocket has arrived at the launchpad. What’s next? appeared first on Digital Trends.

Looking for a unique vacation spot? Have at least $10 million USD burning a hole in your pocket? If so, then you’re just the sort of customer the rather suspiciously named “GRU Space” is looking for. They’re currently taking non-refundable $1,000 deposits from individuals looking to stay at their currently non-existent hotel on the lunar surface. They don’t expect you’ll be able to check in until at least the early 2030s, and the $1K doesn’t actually guarantee you’ll be selected as one of the guests who will be required to cough up the final eight-figure ticket price before liftoff, but at least admission into the history books is free with your stay.

The whole idea reminds us of Mars One, which promised to send the first group of colonists to the Red Planet by 2024. They went bankrupt in 2019 after collecting ~$100 deposits from more than 4,000 applicants, and we probably don’t have to tell you that they never actually shot anyone into space. Admittedly, the Moon is a far more attainable goal, and the commercial space industry has made enormous strides in the decade since Mars One started taking applications. But we’re still not holding our breath that GRU Space will be leaving any mints on pillows at one-sixth gravity.

Speaking of something which actually does have a chance of reaching the Moon on time — on Saturday, NASA rolled out the massive Space Launch System (SLS) rocket that will carry a crew of four towards our nearest celestial neighbor during the Artemis II mission. There’s still plenty of prep work to do, including a dress rehearsal that’s set to take place in the next couple of weeks, but we’re getting very close. Artemis II won’t actually land on the Moon, instead performing a lunar flyby, but it will still be the first time we’ve sent humans beyond Low Earth Orbit (LEO) since Apollo 17 in 1972. We can’t wait for some 4K Earthrise video.

In more terrestrial matters, Verizon users are likely still seething from the widespread outages that hit them mid-week. Users from all over the US reported losing cellular service for several hours, though outage maps at the time showed the Northeast was hit particularly hard. At one point, the situation got so bad that Verizon’s own system status page crashed. In a particularly embarrassing turn of events, some of the other cellular carriers actually reached out to their customers to explain it wasn’t their fault if they couldn’t reach friends and family on Verizon’s network. Oof.

Speaking of phones, security researchers recently unveiled WhisperPair, an attack targeting Bluetooth devices that utilize Google’s Fast Pair protocol. When the feature is implemented correctly, a Bluetooth accessory should ignore pairing requests unless it’s actually in pairing mode, but the researchers found that many popular models (including Google’s own Pixel Buds Pro 2) can be tricked into accepting an unsolicited pairing request. While an attacker hijacking your Bluetooth headset might not seem like a huge deal at first, consider that it could allow them to record your conversations and track your location via Google’s Find Hub network.

Incidentally, something like WhisperPair is the kind of thing we’d traditionally leave for Jonathan Bennett to cover in his This Week in Security column, but as regular readers may know, he had to hang up his balaclava back in December. We know many of you have been missing your weekly infosec dump, but we also know it’s not the kind of thing that just anyone can take over. We generally operate under a “Write What You Know” rule around here, and that means whoever takes over the reins needs to know the field well enough to talk authoritatively about it. Luckily, we think we’ve found just the hacker for the job, so hopefully we’ll be able to start it back up in the near future.

Finally, we don’t generally promote crowdfunding campaigns due to their uncertain nature, but we’ll make an exception for the GameTank. We’ve covered the open hardware 6502 homebrew game console here in the past, and even saw it in the desert of the real (Philadelphia) at JawnCon 0x2 in October. The project really embraces the retro feel of using a console from the 1980s, even requiring you to physically swap cartridges to play different games. It’s a totally unreasonable design choice from a technical perspective, given that an SD card could hold thousands of games at once, but of course, that’s not the point. There’s a certain joy in plugging in a nice chunky cartridge that you just can’t beat.

See something interesting that you think would be a good fit for our weekly Links column? Drop us a line, we’ve love to hear about it.

NASA’s massive Space Launch System rocket crept to its Florida launch pad today at a top speed of about 1 mph, marking the first step in a journey that will eventually send astronauts around the moon for the first time in more than 50 years.

The 4-mile trek to Launch Complex 39B at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center began at 7 a.m. ET (4 a.m. PT) and lasted nearly 12 hours. Because the rocket with its mobile launcher stands more than 300 feet tall and weighs millions of pounds, the trip required the use of a crawler-transporter — the same vehicle used for the Apollo and space shuttle programs, now upgraded for NASA’s Artemis moon program.

Liftoff for the Artemis 2 mission could come as early as Feb. 6, but there’s lots to be done in the weeks ahead. After today’s rollout, the mission team will conduct a thorough checkout of the Space Launch System and its Orion crew spacecraft. Then there’ll be a “wet dress rehearsal,” during which the launch team will fuel the rocket and count down to T-minus 29 seconds.

“We have, I think, zero intention of communicating an actual launch date until we get through wet dress,” NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman told reporters.

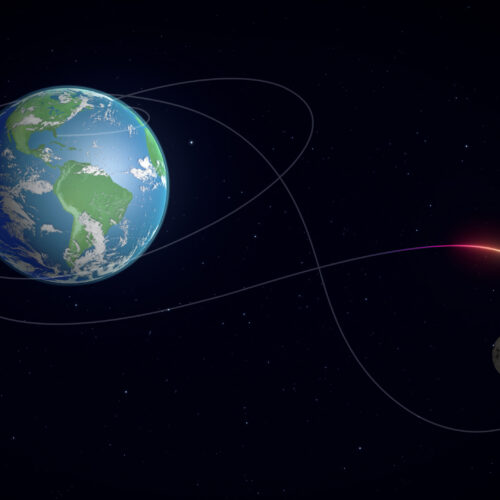

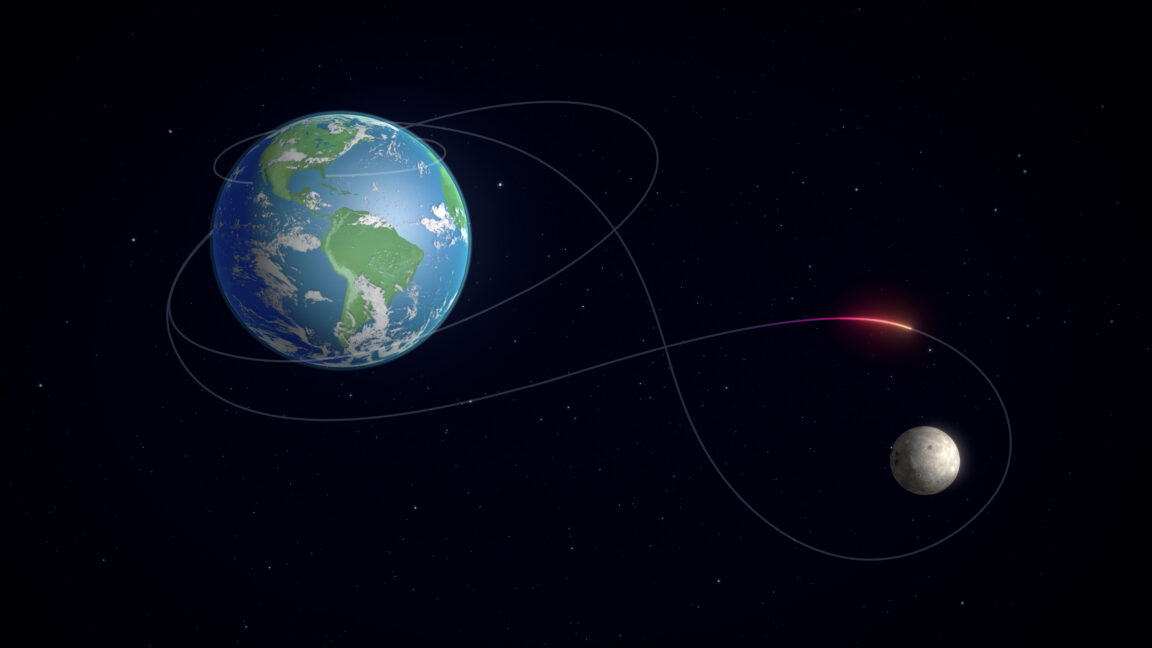

Artemis 2 is slated to send three NASA astronauts and one Canadian astronaut on a 10-day journey tracing a figure-8 route around the moon. The trip will take them as far as 4,800 miles beyond the lunar far side — farther out than any human has gone before.

One of the crew members, Christina Koch, recalled an exchange she had with Apollo 13’s Fred Haise at a commemorative event. “Before I even said, ‘Hello, sir, great to see you,’ he goes, ‘I heard you’re going to break our record,'” she said.

Mission commander Reid Wiseman said he’s already seeing the moon in a different light.

“One of the most magical things for me in this experience is, when I looked out a few mornings ago, there was a beautiful crescent in the morning sunrise, and I truly just see the far side,” he said. “You just think about all the landmarks we’ve been studying on that far side, and how amazing that will look. And seeing Earthrise, just flipping the moon over and seeing it from the other perspective, is what I think when I look out right now.”

Good morning, Moon. See you next month? pic.twitter.com/1FwBmxMEyZ

— Reid Wiseman (@astro_reid) January 15, 2026

Although Artemis 2 will be historic in its own right, the mission’s main purpose is to prepare the way for Artemis 3, which will put humans on the lunar surface for the first time since Apollo 17 in 1972. That mission is officially set for no earlier than mid-2027, but industry experts expect the schedule to slip.

During today’s news briefing, Isaacman took an even longer view. “This is the start of a very long journey,” he said. “I hope someday my kids are going to be watching, maybe decades into the future, the Artemis 100 mission.”

Isaacman, who served as the billionaire CEO of the Shift4 payment processing company before becoming NASA’s chief last month, said that America’s space effort is sending humans back to the moon “to figure out the orbital and lunar economy, for all of the science and discovery possibilities that are out there, to inspire my kids, your kids, kids all around the world, to want to grow up and contribute to this unbelievable endeavor that we’re on right now.”

Several companies with a presence in the Seattle area are already part of that lunar economy. For example, L3Harris’ facility in Redmond has been building thrusters for NASA’s Orion spacecraft. Seattle-based Interlune is planning to bring helium-3 and other lunar resources back to Earth. And Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin space venture, headquartered in Kent, is building a Blue Moon lander that’s meant to put Artemis crews on the lunar surface starting in 2030.

Blue Origin’s New Glenn rocket is expected to send an uncrewed cargo version of the Blue Moon lander to the moon sometime in the next few months. Isaacman hinted that Blue Origin could be in for a bigger role in the lunar economy as the Artemis program hits its stride.

“I will say I did meet with both Blue Origin and SpaceX on their acceleration plans. These are both very good plans,” he said. “If we are on track, we should be watching an awful lot of New Glenns and Starships launch in the years ahead.”

KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, Florida—The rocket NASA is preparing for sending four astronauts on a trip around the Moon will emerge from its assembly building on Florida's Space Coast early Saturday for a slow crawl to its seaside launch pad.

Riding atop one of NASA's diesel-powered crawler transporters, the Space Launch System rocket and its mobile launch platform will exit the Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy Space Center around 7:00 am EST (11:00 UTC). The massive tracked transporter, certified by Guinness as the world's heaviest self-propelled vehicle, is expected to cover the four miles between the assembly building and Launch Complex 39B in about eight to 10 hours.

The rollout marks a major step for NASA's Artemis II mission, the first human voyage to the vicinity of the Moon since the last Apollo lunar landing in December 1972. Artemis II will not land. Instead, a crew of four astronauts will travel around the far side of the Moon at a distance of several thousand miles, setting the record for the farthest humans have ever ventured from Earth.

© NASA

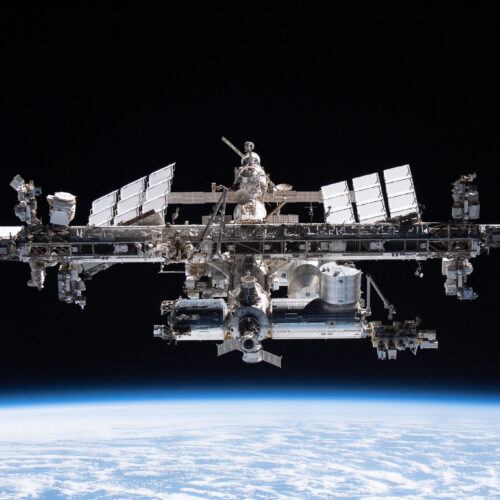

Two Americans, a Japanese astronaut, and a Russian cosmonaut returned to Earth early Thursday after 167 days in orbit, cutting short their stay on the International Space Station by more than a month after one of the crew members encountered an unspecified medical issue last week.

The early homecoming culminated in an on-target splashdown in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of San Diego at 12:41 am PST (08:41 UTC) inside a SpaceX Crew Dragon spacecraft. The splashdown occurred minutes after the Dragon capsule streaked through the atmosphere along the California coastline, with sightings of Dragon's fiery trail reported from San Francisco to Los Angeles.

Four parachutes opened to slow the capsule for the final descent. Zena Cardman, NASA's commander of the Crew-11 mission, radioed SpaceX mission control moments after splashdown: "It feels good to be home, with deep gratitude to the teams who got us there and back."

© NASA/Bill Ingalls

Over the course of its nearly 30 years in orbit, the International Space Station has played host to more “firsts” than can possibly be counted. When you’re zipping around Earth at five miles per second, even the most mundane of events takes on a novel element. Arguably, that’s the point of a crewed orbital research complex in the first place — to study how humans can live and work in an environment that’s so unimaginably hostile that something as simple as eating lunch requires special equipment and training.

Today marks another unique milestone for the ISS program, albeit a bittersweet one. Just a few hours ago, NASA successfully completed the first medical evacuation from the Station, cutting the Crew-11 mission short by at least a month. By the time this article is released, the patient will be back on terra firma and having their condition assessed in California. This leaves just three crew members on the ISS until NASA’s Crew-12 mission can launch in early February, though it’s possible that mission’s timeline will be moved up.

To respect the privacy of the individual involved, NASA has been very careful not to identify which member of the multi-nation Crew-11 mission is ill. All of the communications from the space agency have used vague language when discussing the specifics of the situation, and unless something gets leaked to the press, there’s an excellent chance that we’ll never really know what happened on the Station. But we can at least piece some of the facts together.

On January 7th, Kimiya Yui of Japan was heard over the Station’s live audio feed requesting a private medical conference (PMC) with flight surgeons before the conversation switched over to a secure channel. At the time this was not considered particularly interesting, as PMCs are not uncommon and in the past have never involved anything serious. Life aboard the Station means documenting everything, so a PMC could be called to report a routine ailment that we wouldn’t give a second thought to here on Earth.

But when NASA later announced that the extravehicular activity (EVA) scheduled for the next day was being postponed due to a “medical concern”, the press started taking notice. Unlike what we see in the movies, conducting an EVA is a bit more complex than just opening a hatch. There are many hours of preparation, tests, and strenuous work before astronauts actually leave the confines of the Station, so the idea that a previously undetected medical issue could come to light during this process makes sense. That said, Kimiya Yui was not scheduled to take part in the EVA, which was part of a long-term project of upgrading the Station’s aging solar arrays. Adding to the mystery, a representative for Japan’s Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) told Kyodo News that Yui “has no health issues.”

This has lead to speculation from armchair mission controllers that Yui could have requested to speak to the flight surgeons on behalf of one of the crew members that was preparing for the EVA — namely station commander Mike Fincke and flight engineer Zena Cardman — who may have been unable or unwilling to do so themselves.

Within 24 hours of postponing the EVA, NASA held a press conference and announced Crew-11 would be coming home ahead of schedule as teams “monitor a medical concern with a crew member”. The timing here is particularly noteworthy; the fact that such a monumental decision was made so quickly would seem to indicate the issue was serious, and yet the crew ultimately didn’t return to Earth for another week.

While the reusable rockets and spacecraft of SpaceX have made crew changes on the ISS faster and cheaper than they were during the Shuttle era, we’re still not at the point where NASA can simply hail a Dragon like they’re calling for an orbital taxi. Sending up a new vehicle to pickup the ailing astronaut, while not impossible, would have been expensive and disruptive as one of the Dragon capsules in rotation would have had to be pulled from whatever mission it was assigned to.

So unfortunately, bringing one crew member home means everyone who rode up to the Station with them needs to leave as well. Given that each astronaut has a full schedule of experiments and maintenance tasks they are to work on while in orbit, one of them being out of commission represents a considerable hit to the Station’s operations. Losing all four of them at once is a big deal.

Granted, not everything the astronauts were scheduled to do is that critical. Tasks range form literal grade-school science projects performed as public outreach to long-term medical evaluations — some of the unfinished work will be important enough to get reassigned to another astronaut, while some tasks will likely be dropped altogether.

But the EVA that Crew-11 didn’t complete represents a fairly serious issue. The astronauts were set to do preparatory work on the outside of the Station to support the installation of upgraded roll-out solar panels during an EVA scheduled for the incoming Crew-12 to complete later on this year. It’s currently unclear if Crew-12 received the necessary training to complete this work, but even if they have, mission planners will now have to fit an unforeseen extra EVA into what’s already a packed schedule.

Having to bring the entirety of Crew-11 back because of what would appear to be a non-life-threatening medical situation with one individual not only represents a considerable logistical and monetary loss to the overall ISS program in the immediate sense, but will trigger a domino effect that delays future work. It was a difficult decision to make, but what if it didn’t have to be that way?

In other timeline, the ISS would have featured a dedicated “lifeboat” known as the Crew Return Vehicle (CRV). A sick or injured crew member could use the CRV to return to Earth, leaving the spacecraft they arrived in available for the remaining crew members. Such a capability was always intended to be part of the ISS design, with initial conceptual work for the CRV dating back to the early 1990s, back when the project was still called Space Station Freedom. Indeed, the idea that the ISS has been in continuous service since 2000 without such a failsafe in place is remarkable.

Unfortunately, despite a number of proposals for a CRV, none ever made it past the prototype stage. In practice, it’s a considerable engineering challenge. A space lifeboat needs to be cheap, since if everything goes according to plan, you’ll never actually use the thing. But at the same time, it must be reliable enough that it could remain attached to the Station for years and still be ready to go at a moment’s notice.

In practice, it was much easier to simply make sure there are never more crew members on the Station than there are seats in returning spacecraft. It does mean that there’s no backup ride to Earth in the event that one of the visiting vehicles suffers some sort of failure, but as we saw during the troubled test flight of Boeing’s CST-100 in 2024, even this issue can be resolved by modifications to the crew rotation schedule.

Everything that happens aboard the International Space Station represents an opportunity to learn something new, and this is no different. When the dust settles, you can be sure NASA will commission a report to dives into every aspect of this event and tries to determine what the agency could have done better. While the ISS itself may not be around for much longer, the information can be applied to future commercial space stations or other long-duration missions.

Was ending the Crew-11 mission the right call? Will the loses and disruptions triggered by its early termination end up being substantial enough that NASA rethinks the CRV concept for future missions? There are many questions that will need answers before it’s all said and done, and we’re eager to see what lessons NASA takes away from today.

In remarks this week to a Texas space organization, a key Senate staff member said an "extension" of the International Space Station is on the table and that NASA needs to accelerate a program to replace the aging station with commercial alternatives.

Maddy Davis, a space policy staff member for US Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, made the comments to the Texas Space Coalition during a virtual event.

Cruz is chairman of the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation and has an outsized say in space policy. As a senator from Texas, he has a parochial interest in Johnson Space Center, where the International Space Station Program is led.

© NASA

It’s turned into an unusual mission for SpaceX’s Crew-11. Instead of remaining at the International Space Station (ISS) for the full duration of their mission, the four crew members are coming home a month early due to a medical issue with one of the astronauts. Crew-11 departed the ISS on Wednesday afternoon and is due […]

The post How to watch SpaceX Crew-11 splash down a month early appeared first on Digital Trends.

Read more of this story at Slashdot.

Among other things, the James Webb Space Telescope is designed to get us closer to finding habitable worlds around faraway stars. From its perch a million miles from Earth, Webb's huge gold-coated mirror collects more light than any other telescope put into space.

The Webb telescope, launched in 2021 at a cost of more than $10 billion, has the sensitivity to peer into distant planetary systems and detect the telltale chemical fingerprints of molecules critical to or indicative of potential life, like water vapor, carbon dioxide, and methane. Webb can do this while also observing the oldest observable galaxies in the Universe and studying planets, moons, and smaller objects within our own Solar System.

Naturally, astronomers want to get the most out of their big-budget observatory. That's where NASA's Pandora mission comes in.

© Blue Canyon Technologies