Reading view

2 Venezuelans Convicted in US for Using Malware to Hack ATMs

Dozens of Venezuelan nationals have been charged by the US for their role in ATM jackpotting attacks.

The post 2 Venezuelans Convicted in US for Using Malware to Hack ATMs appeared first on SecurityWeek.

New Reports Reinforce Cyberattack’s Role in Maduro Capture Blackout

US officials told The New York Times that cyberattacks were used to turn off the lights in Caracas and disrupt air defense radars.

The post New Reports Reinforce Cyberattack’s Role in Maduro Capture Blackout appeared first on SecurityWeek.

Mastang Panda Uses Venezuela News to Spread LOTUSLITE Malware

What U.S. – China Cooperation Means for the World

OPINION -- China was very critical of the capture of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro last week. The spokesperson for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs said the U.S. action was “blatant interference” in Venezuela and a violation of international law.

Mr. Maduro was accused of working with Columbian guerrilla groups to traffic cocaine into the U.S. as part of a “narco-terrorism” conspiracy. Of all countries, China should appreciate the need to stop Mr. Maduro from smuggling these illicit drugs into the U.S., killing tens of thousands of Americans. China experienced this in the Opium War of 1839-1842, when Great Britain forced opium on China, despite government protestations, resulting in the humiliating Treaty of Nanjing, ceding Hong Kong to Great Britain. Mr. Maduro was violating U.S. laws, in a conspiracy to aid enemies and kill innocent Americans. Fortunately, the U.S. had the political will, and military might, to quickly and effectively put an end to this assault. China should understand this and withhold criticism, despite their close relationship with Mr. Maduro and Venezuela.

The scheduled April meeting of presidents Donald Trump and Xi Jinping will hopefully ease tension related to the South China Sea and Taiwan. The meeting will also offer an opportunity of the two presidents to elaborate on those transnational issues that the U.S. and China can work together on, for the common good.

The National Security Strategy of 2025 states that deterring a conflict over Taiwan is a priority and does not support any unilateral change to the status quo in the Taiwan Strait. It also states that one-third of global shipping passes annually through the South China Sea and its implications for the U.S. economy are obvious.

The Cipher Brief brings expert-level context to national and global security stories. It’s never been more important to understand what’s happening in the world. Upgrade your access to exclusive content by becoming a subscriber.

The April meeting will permit Messrs. Trump and Xi to candidly discuss the South China Sea and Taiwan and ensure that there are guardrails to prevent conflict. Quiet and effective diplomacy is needed to address these issues, and the Trump – Xi meeting could establish the working groups and processes necessary to ensure the U.S. and China do not stumble into conflict.

Also important are the transnational issues that require the attention of the U.S. and China. This shouldn’t be too difficult, given the history of cooperation between the U.S. and China, primarily in the 1980s and 1990s.

Indeed, it was China’s Chairman Deng Xiaoping who approved cooperation with the U.S. on the collection and sharing of intelligence on the Soviet Union.

China opposed the December 1979 Soviet Union invasion of Afghanistan and worked with the U.S. to provide weapons and supplies to the resistance forces in Afghanistan – who eventually prevailed, with the Soviet Union admitting defeat and pulling out of Afghanistan in 1989. The war in Afghanistan cost the Soviet Union immense resources, lives and prestige, weakening the Soviet Union and contributing to its later dissolution.

After the 1979 normalization of relations, the U.S. and China cooperated on a few transnational issues: nuclear nonproliferation; counternarcotics, focusing on Southeast Asia’s Golden Triangle and the heroin from Burma going into China and the U.S.; counterterrorism and the sharing of intelligence on extremist networks.

In 2002, Secretary of State Colin Powell asked China to assist with the denuclearization of North Korea. The following year, China hosted the Six-Party Talks on North Korea’s nuclear program and actively assisted convincing North Korea, in the Joint Statement of September 19, 2005, to commit to complete and verifiable dismantlement of all nuclear weapons and nuclear weapons programs.

China also cooperated with the U.S. on public health issues, like SARS and the avian flu.

Cooperation on these transnational issues was issue-specific, pragmatic, and often insulated from political tensions. Indeed, even during periods of rivalry, functional cooperation persisted when interests overlapped.

Opportunities to Further Enhance Bilateral Cooperation for the Common Good

Although U.S. – China cooperation on counternarcotics is ongoing, specifically regarding the fentanyl crisis, trafficking in cocaine, heroin and methamphetamines also requires close attention. More can be done to enhance bilateral efforts on nuclear nonproliferation, starting with China agreeing to have a dialogue with the U.S. on China’s ambitious nuclear program. Extremist militant groups like ISIS continue to be active, thus requiring better cooperation on counterterrorism. Covid-19 was a wakeup call: there needs to be meaningful cooperation on pandemics. And ensuring that the space domain is used only for peaceful purposes must be a priority, while also ensuring that there are acceptable guidelines for the lawful and moral use of Artificial Intelligence.

U.S. – China cooperation today is more about preventing a catastrophe. The Belgrade Embassy bombing in 1999, when the U.S. accidentally bombed China’s embassy in Belgrade, killing three Chinese officials and the EP-3 incident of 2001, when a Chinese jet crashed into a U.S. reconnaissance plane, killing the Chinese pilot, and China detaining the U.S. crew in Hainan Island are two examples of incidents that could have spiraled out of control. Chinas initially refused to take the telephone calls from Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, both hoping to deescalate these tense developments.

Need a daily dose of reality on national and global security issues? Subscriber to The Cipher Brief’s Nightcap newsletter, delivering expert insights on today’s events – right to your inbox. Sign up for free today.

Thus, crisis management and military de-confliction should be high on the list of subjects to be discussed, with a robust discussion of nuclear risk reduction. Stability in Northeast Asia and a nuclear North Korea, aligned with Russia and viewing the U.S. and South Korea as the enemies, should also be discussed, as well as nuclear nonproliferation.

The April summit between Messrs. Trump and Xi will be an opportunity to candidly discuss Taiwan and the South China Sea, to ensure we do not stumble into conflict.

The summit is also an opportunity to message to the world that the U.S. and China are working on a myriad of transnational issues for the common good of all countries.

The author is the former associate director of national intelligence. All statements of fact, opinion or analysis expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official positions or views of the U.S. government. Nothing in the contents should be construed as asserting or implying U.S. government authentication or information or endorsement of the author’s views.

The Cipher Brief is committed to publishing a range of perspectives on national security issues submitted by deeply experienced national security professionals. Opinions expressed are those of the author and do not represent the views or opinions of The Cipher Brief.

Have a perspective to share based on your experience in the national security field? Send it to Editor@thecipherbrief.com for publication consideration.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief, because national security is everyone’s business.

Why I’m withholding certainty that “precise” US cyber-op disrupted Venezuelan electricity

The New York Times has published new details about a purported cyberattack that unnamed US officials claim plunged parts of Venezuela into darkness in the lead-up to the capture of the country’s president, Nicolás Maduro.

Key among the new details is that the cyber operation was able to turn off electricity for most residents in the capital city of Caracas for only a few minutes, though in some neighborhoods close to the military base where Maduro was seized, the outage lasted for three days. The cyber-op also targeted Venezuelan military radar defenses. The paper said the US Cyber Command was involved.

Got more details?

“Turning off the power in Caracas and interfering with radar allowed US military helicopters to move into the country undetected on their mission to capture Nicolás Maduro, the Venezuelan president who has now been brought to the United States to face drug charges,” the NYT reported.

© Getty Images

Ruling Venezuela with a 2,000 Mile Hammer is Not Likely to End Well

EXPERT OPINION — Rule by proxy just isn’t as simple as the Trump Administration wants to make it sound. While the long-term goals of the Administration in Venezuela are unclear, the tools they appear to want to use are not.

First, the Administration seems to want to dictate policy to the Delcy Rodriguez government through threats of force, which President Trump recently highlighted by suggesting that he had called off a second strike on Venezuela because the regime was cooperating.

Second, the Trump Administration has stated that it will control the oil sales “indefinitely” to, in the words of the Secretary of Energy, “drive the changes that simply must happen in Venezuela.”

Leaving aside the legality and morality of using threats of armed force to seize another country’s natural resources and dictate an unspecified set of “changes”, this sort of rule from a distance is unlikely to work out as intended.

First, attempting to work through the Venezuelan regime will drive a number of choices that the Administration does not appear to have thought through. Propping up an authoritarian regime that is deeply corrupt, violent, and wildly unpopular will over time increasingly alienate the majority of the Venezuelan people and undermine international legitimacy.

Regime leaders, and the upper echelons of their subordinates, are themselves unlikely to quietly depart power or Venezuela itself without substantial guarantees of immunity and probably wealth somewhere else. Absent that, they will have every incentive to throw sand in the works of any sort of process of political transition. Yet facilitating their escape from punishment for their crimes with some amount of their ill-gotten gains is unlikely to be acceptable to the majority of the Venezuelan people.

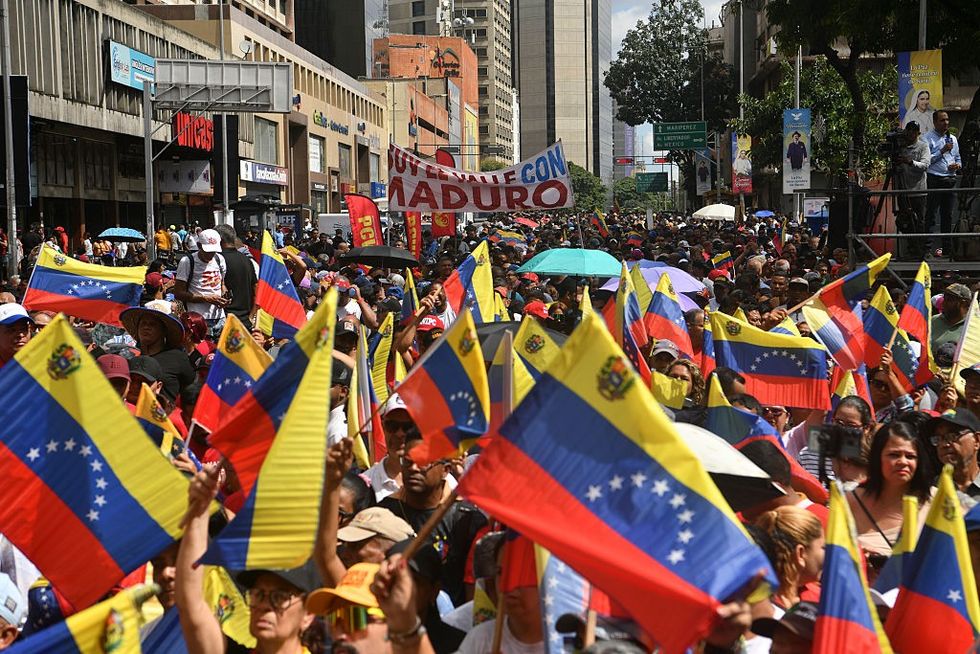

Elements of the regime have already taken steps to crack down on opposition in the streets. The Trump Administration is going to decide how much of this sort of repression is acceptable. Too much tolerance of repression will harm the already-thin legitimacy of this policy, particularly among the Venezuelan people, the rest of the hemisphere, and those allies the Administration hasn’t managed to alienate. Too little tolerance will encourage street protests and potentially anti-regime violence and threaten regime stability.

The Cipher Brief brings expert-level context to national and global security stories. It’s never been more important to understand what’s happening in the world. Upgrade your access to exclusive content by becoming a subscriber.

Opposition leader Maria Corina Machado has announced that she plans to return to Venezuela in the near future, which could highlight the choices the Administration faces. Some parts of the Rodriguez government will want to crack down on her supporters and make their lives as difficult as possible. The Trump Administration is going to have to think hard about how to react to that.

The tools of violence from a distance, or even abductions by Delta Force from over the horizon, are not well calibrated to deal with these dilemmas.

The Venezuelan regime appears to be heavily factionalized and punishing Delcy Rodriguez, which President Trump has threatened, could benefit other factions, for example, the Minister of the Interior or the Minister of Defense, both allegedly her rivals for power.

Unless the Administration can count on perfect intelligence about what faction is responsible for each disfavored action and precisely and directly respond, we are likely to see different factions, and even elements of the opposition, undertake “false flag” activity intended to cause the U.S. to strike their rivals.

Actions to punish or compel the regime also run the risk of collateral damage, in particular civilian casualties which will undermine support for U.S. policy both in Venezuela and abroad and potentially bolster support for the regime. And intelligence on the ground is not going to be perfect and airstrikes or raids will almost certainly cause collateral damage despite the incredible capabilities of the U.S. intelligence community and the U.S. military.

Need a daily dose of reality on national and global security issues? Subscriber to The Cipher Brief’s Nightcap newsletter, delivering expert insights on today’s events – right to your inbox. Sign up for free today.

Secondly, assuming that the Administration doesn’t intend to use the proceeds of sales of Venezuelan oil to build the White House ballroom, it’s unclear what mechanisms they plan to use to ensure that those proceeds benefit the Venezuelan people.

The Venezuelan regime is deeply corrupt. Utilizing the Venezuelan government to distribute proceeds from oil sales is just a way of ensuring that regime elites continue to siphon off cash or use that money to reward their followers, punish their opponents, or coopt potential rivals by buying them off.

Assuming that the U.S. could, in fact, somehow track the vast majority of the funds from oil sales and ensure that they are not misused, this would again undermine the unity and inner workings of a regime built on buying off factions and elites. That would likely encourage those factions to find other ways of extracting funds—for example, increased facilitation of drug shipments or shakedowns of local firms supporting the reconstruction of the oil sector.

Yet the U.S. is not at all likely to have a granular view of what happens to that money. The U.S. intelligence community, while capable of a great many things, cannot track where most of these funds go or who is raking off how much.

In Iraq and Afghanistan, where the U.S. had tens of thousands of soldiers, spies, advisors, and bureaucrats and was directly funding large parts of those governments, staggering levels of corruption existed and at times, helped fund warlords and faction leaders who undermined stability. We even managed to fund our adversaries at times.

In Venezuela, by contrast, we might have an embassy.

Unless the problem of how to monitor where the money goes can be solved, the U.S. will be supporting and funding a corrupt regime that feathers its own nest and undermines the transition to democracy.

Ruling from a distance, or even trying to force a political transition from a distance, drives a number of choices that the Administration clearly hasn’t thought through. And the tools the Administration is choosing to use; force from over the horizon and the control over the flow of some funds, aren’t matched well enough or sufficiently nuanced to accomplish the ends they claim to want to achieve.

Given that, it’s unlikely this will end well.

The Cipher Brief is committed to publishing a range of perspectives on national security issues submitted by deeply experienced national security professionals.

Opinions expressed are those of the author and do not represent the views or opinions of The Cipher Brief.

Have a perspective to share based on your experience in the national security field? Send it to Editor@thecipherbrief.com for publication consideration.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief, because national security is everyone’s business.

Trump’s Power Doctrine: A $1.5 Trillion Military, Greenland Ambitions, and a World Ruled by Force

OPINION — “After long and difficult negotiations with Senators, Congressmen, Secretaries, and other Political Representatives, I have determined that, for the Good of our Country, especially in these very troubled and dangerous times, our Military Budget for the year 2027 should not be $1 Trillion Dollars, but rather $1.5 Trillion Dollars. This will allow us to build the ‘Dream Military’ that we have long been entitled to and, more importantly, that will keep us SAFE and SECURE, regardless of foe.”

That was part of a Truth Social message from President Trump posted last Wednesday afternoon and illustrates the emphasis on increasing U.S. military power by him and top administration officials since the successful U.S. January 3, raid in Venezuela that captured its former-President Nicolas Maduro and his wife.

As it should, public attention has been focused on Trump’s apparent desire to project force as he publicly savors the plaudits arising from not only the Venezuela operation, but also the June 2025 Operation Midnight Hammer bombing of three Iranian nuclear facilities.

Most focus this past week has been paid to remarks Trump made to New York Times reporters during their more than two hour interview last Thursday.

At that time, when asked if there are any limits on his global powers, Trump said, "Yeah, there is one thing. My own morality. My own mind. It’s the only thing that can stop me.”

Trump added, “I don’t need international law. I’m not looking to hurt people.” Asked about whether his administration needed to abide by international law, Trump said, “I do,” but added, “it depends what your definition of international law is.”

Attention is also correctly being paid to remarks Trump’s Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller made last Tuesday during an interview with CNN.

“We live in a world in which you can talk all you want about international niceties and everything else,” Miller told CNN’s Jake Tapper, “But we live in a world, in the real world … that is governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power. These are the iron laws of the world.”

It is against that Trump open-stress-on-power background that I will discuss below a few other incidents last week that could indicate future events. But first I want to explore Trump’s obsession with taking over Greenland, which was also illustrated during the Times interview.

The Cipher Brief brings expert-level context to national and global security stories. It’s never been more important to understand what’s happening in the world. Upgrade your access to exclusive content by becoming a subscriber.

In 1945, at the end of World War II fighting in Europe, the United States had 17 bases and military installations in Greenland with thousands of soldiers. Today, there is only one American base – U.S. Pituffik Space Base in northwest Greenland, formerly known as Thule Air Base.

From this base today some 200 U.S. Air Force and Space Force personnel, plus many more contractors, carry out ballistic missile early warnings, missile defense, and space surveillance missions supported by what the Space Force described as an “Upgraded Early Warning Radar weapon system.” That system includes “a phased-array radar that detects and reports attack assessments of sea-launched and intercontinental ballistic missile threats in support of [a worldwide U.S.] strategic missile warning and missile defense [system],” according to a Space Force press release.

The same radar also supports what Space Force said is “Space Domain Awareness by tracking and characterizing objects in orbit around the earth.”

Under the 1951 U.S.-Denmark defense agreement, the U.S., with Denmark’s assent, can create new “defense areas” in Greenland “necessary for the development of the defense of Greenland and the rest of the North Atlantic Treaty area, and which the Government of the Kingdom of Denmark is unable to establish and operate singlehanded.”

The agreement says further: “the Government of the United States of America, without compensation to the Government of the Kingdom of Denmark, shall be entitled within such defense area and the air spaces and waters adjacent thereto to improve and generally to fit the area for military use.”

That apparently is not enough freedom for President Trump, still a real estate man. As he explained last week to the Times reporters, “Ownership is very important, because that’s what I feel is psychologically needed for success. I think that ownership gives you a thing that you can’t do with, you’re talking about a lease or a treaty. Ownership gives you things and elements that you can’t get from just signing a document.”

This long-held Trump view that he must have Greenland was explored back in 2021. After his first term as President, Trump was interviewed by Susan Glasser and Peter Baker for the book they were writing, and they asked Trump at that time why he wanted Greenland.

Four years ago, Trump explained, “You take a look at a map. So I’m in real estate. I look at a [street] corner, I say, ‘I gotta get that store for the building that I’m building,’ et cetera. You know, it’s not that different. I love maps. And I always said, ‘Look at the size of this [Greenland], it’s massive, and that should be part of the United States.’ It’s not different from a real-estate deal. It’s just a little bit larger, to put it mildly.”

For all Trump’s repeated threats to seize Greenland militarily, it’s doubtful that will happen. Secretary of State Marco Rubio is scheduled to meet with Danish and Greenland counterparts this week, and afterwards the situation should become clearer.

Context is another test for analyzing Trump statements, and that seems to be the case when looking at his call for a $1.5 trillion fiscal 2027 defense budget.

Need a daily dose of reality on national and global security issues? Subscriber to The Cipher Brief’s Nightcap newsletter, delivering expert insights on today’s events – right to your inbox. Sign up for free today.

Last Wednesday, hours before Trump made his Truth Social FY 2027 budget statement, the White House released an Executive Order (EO) entitled, Prioritizing The Warfighter In Defense Contracting. The EO called for holding defense contractors accountable and targeted those who engaged in stock buybacks or issued dividends while “underperforming” on government contracts. According to one Washington firm, the Trump EO represented “one of the most aggressive federal interventions into corporate financial decisions in recent memory.”

The EO caused shares of defense stocks to fall. Lockheed Martin fell 4.8%, Northrop Grumman 5.5%, and General Dynamics 3.6% during that afternoon’s stock exchange trading in New York. After the stock market closed, Trump released his Truth Social message calling for the $1.5 trillion FY 2027 defense budget and the next day, January 8, defense stocks experienced a sharp rebound. Lockheed Martin rebounded with gains of around 7%; Northrop Grumman rose over 8%; and General Dynamics gained around 4%.

Trump has not spoken publicly about the $1.5 trillion for FY 2027, but in his first message, he said the added funds would come from tariffs. He wrote, “Because of tariffs and the tremendous income that they bring, amounts being generated, that would have been unthinkable in the past, we are able to easily hit the $1.5 trillion dollar number.”

If that were not enough, Trump added that the new funding would produce “an unparalleled military force, and having the ability to, at the same time, pay down debt, and likewise, pay a substantial dividend to moderate income patriots within our country!”

What can be believed?

The nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB) said the $500 billion annual increase in defense spending would be nearly twice as much as the expected yearly tariff revenue, and the spending increase would push the national debt $5.8 trillion higher over the next decade. CRFB added, “Given the $175 billion appropriated to the defense budget under the [2025] One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), there is little case for a near-term increase in military spending.”

I should point out that the FY 2026 $901 billion defense appropriations bill has yet to pass the Congress.

One more event from last week needing attention involves Venezuela.

Last Tuesday January 6, 2026, as Delcy Rodriguez, former Vice President, was sworn in as Venezuela's interim president, General Javier Marcano Tabata. the military officer closest to Maduro as his head of the presidential honor guard and director of the DGCIM, the Venezuelan military counterintelligence agency, was arrested and jailed, according to El Pais Caracas.

Marcano Tabata was labeled a traitor and accused of facilitating the kidnapping of Maduro by providing the U.S. with exactly where Maduro and First Lady Cilia Flores were sleeping, and identifying blind spots in the Cuban-Venezuelan security ring protecting them, according to El Pais Caracas.

What’s the U.S. responsibility toward Marcano Tabata if the El Pais Caracas facts are correct ?

I want to end this column with another Trump statement last week that stuck in my mind because of its implications.

It came up last Friday after Trump, in the White House East Room, started welcoming more than 20 oil and gas executives invited to discuss the situation in Venezuela.

“We have many others that were not able to get in…If we had a ballroom, we'd have over a thousand people. Everybody wanted. I never knew your industry was that big. I never knew you had that many people in your industry. But, here we are.”

Trump then paused, got up and turned to look through the glass door behind him that showed the excavation for the new ballroom saying, “I got to look at this myself. Wow. What a view…Take a look, you can see a very big foundation that's moving. We're ahead of schedule in the ballroom and under budget. It's going to be I don't think there'll be anything like it in the world, actually. I think it will be the best.”

He then said the remark I want to highlight, “The ballroom will seat many and it'll also take care of the inauguration with bulletproof glass-drone proof ceilings and everything else unfortunately that today you need.”

Who, other than Trump, would think that the next President of the United States would need to hold his inauguration indoors, inside the White House ballroom, with bullet-proof windows and a roof that protects from a drone attack?

The Cipher Brief is committed to publishing a range of perspectives on national security issues submitted by deeply experienced national security professionals. Opinions expressed are those of the author and do not represent the views or opinions of The Cipher Brief.

Have a perspective to share based on your experience in the national security field? Send it to Editor@thecipherbrief.com for publication consideration.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief, because national security is everyone’s business.

SEC Chair: Fate of Rumored Venezuelan Bitcoin Stash ‘Remains to Be Seen’

Bitcoin Magazine

SEC Chair: Fate of Rumored Venezuelan Bitcoin Stash ‘Remains to Be Seen’

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission Chair Paul Atkins said today that it remains unclear whether the U.S. government will move to seize the widely discussed Bitcoin holdings rumored to be tied to Venezuela, an uncertainty that comes as Washington seeks to bring greater regulatory clarity to digital asset markets.

Atkins told Fox Business the question of pursuing the so‑called Venezuela Bitcoin stash — variously estimated at roughly 600,000 BTC, or about $56 billion to $67 billion at current prices — is “still to be seen” and is being handled by other parts of the administration.

“I leave that to others to deal with. That’s not my focus,” Atkins said, underscoring that the SEC is not currently prioritizing asset confiscation.

Rumors in crypto and intelligence circles have pointed to a massive “shadow reserve” of Bitcoin allegedly accumulated by the Venezuelan government through gold sales, oil deals settled in stablecoins, and other transactions dating back to 2018.

If verified and under U.S. control, such a reserve would rank among the largest Bitcoin holdings globally.

But independent blockchain analysts note that there is no verifiable on‑chain evidence yet linking wallets containing such amounts to Venezuela’s government, and publicly traceable addresses connected to state entities reflect only a tiny fraction of the rumored holdings.

BREAKING:

— Bitcoin Magazine (@BitcoinMagazine) January 12, 2026SEC Chair Paul Atkins says it "remains to be seen" if the US takes Venezuela's reported $60 billion in #Bitcoin holdings

pic.twitter.com/qeukJX6Dhm

Bitcoin and CLARITY Act update

Atkins pivoted quickly from the Venezuela question to highlight ongoing legislative efforts in Congress aimed at clarifying the regulatory framework for digital assets.

“This week is an important week because the Senate is taking up a bipartisan bill that will bring clarity and certainty to the crypto world,” he said, referring to a measure designed to delineate oversight responsibilities between the SEC and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC).

The bill — backed by members of both parties and anticipated to be marked up this week — represents the next step in positioning the U.S. as a global leader in digital asset markets, Atkins said.

He also cited the Genius Act, passed late last year, as the first statute formally recognizing crypto assets under U.S. law, and credited it with helping to bring regulatory clarity to stablecoin frameworks.

Atkins expressed optimism that with clearer rules, markets will gain much‑needed certainty around products and oversight.

He noted ongoing collaboration with the new CFTC chairman and reiterated the SEC’s commitment to enforcing future regulations once enacted.

While ethical questions around public officials and crypto business interests remain under Congressional purview, Atkins said the immediate priority is a regulatory regime that reduces market ambiguity and supports investor confidence.

This post SEC Chair: Fate of Rumored Venezuelan Bitcoin Stash ‘Remains to Be Seen’ first appeared on Bitcoin Magazine and is written by Micah Zimmerman.

Now Comes the Hard Part in Venezuela

EXPERT PERSPECTIVE — Now comes the hard part in Venezuela. Dictator Nicolas Maduro and his wife are gone but the regime is still in power. Most Venezuelans, particularly in the diaspora, are pleased and relieved. Many are also apprehensive.

The Trump administration has decided to compel the cooperation of Maduro’s Vice President, Delcy Rodriguez, now interim president. It is not at all assured that she will be a reliable partner. The U.S. decision to work with those still in control was logical even if disappointing to some in the democratic opposition which, after all, won the presidential election overwhelmingly in late July of 2024. The opposition’s base of support dwarfs that of the regime but the military, intelligence services and police are all still loyal to the regime - at least for the time being. The Trump administration believes the cooperation of these elements of the regime will be necessary for the Trump administration to implement its plans for the country without further U.S. police and military actions on the ground.

Need a daily dose of reality on national and global security issues? Subscriber to The Cipher Brief’s Nightcap newsletter, delivering expert insights on today’s events – right to your inbox. Sign up for free today.

The Trump administration has said we will be taking over the oil sector and President Trump himself has announced his intention to persuade the U.S. private sector to return to Venezuela to rebuild the sector. Oil production in Venezuela has declined by two thirds since Hugo Chavez, Maduro’s predecessor, was elected in 1998. This unprecedented decline was due to incompetent management, undercapitalization and corruption. Had Chevron not opted to stay in the country under difficult circumstances, the production numbers would look even worse. Resurrecting the oil sector will take time, money and expertise. The return of the U.S. oil companies and the infusions of cash that will be required will only happen if an appropriate level of security can be established — and that will require the cooperation of the Venezuelan armed forces and police. Many senior leaders in those sectors are believed to have been deeply complicit in both the abuses and corruption of a government the United Nations said was plausibly responsible for “crimes against humanity.” Two of the regime figures most widely believed to have been, along with Maduro himself, the architects of the Bolivarian regime’s repressive governance are still in power, Minister of the Interior Diosdado Cabello and Minister of Defense General Vladimir Portino Lopez. They will need to be watched and not permitted to undermine U.S. efforts to rehabilitate the oil sector and orchestrate a return to legitimate, popularly supported and democratic government.

The Cipher Brief brings expert-level context to national and global security stories. It’s never been more important to understand what’s happening in the world. Upgrade your access to exclusive content by becoming a subscriber.

There are several considerations that the U.S. will need to keep in mind going forward. First, more than 80 percent of Venezuelans now live below the poverty line. Their needs must be addressed . Even the shrinking number of Venezuelans who aligned with the regime are hoping to see their lives improve. Between 2013 and 2023, the country’s GDP contracted by around 70 percent, some believe it may have been as much as 75 percent. As most of Venezuela’s licit economy is essentially moribund and the U.S. will be controlling oil exports, the poor will naturally look to the United States for help. Heretofore, the regime employed food transfers to keep the populace in line. That role should move to the NGO community, the church or even elements of the democratic opposition.

Indeed, it will be important to secure the cooperation of the opposition, notwithstanding the Trump administrations to work with Delcy Rodriguez and company as the opposition represents the majority of Venezuelans inside the country as well as out. It will also be necessary to pay the military and it is not at all clear that the regime elements still in place will have the money to do so once oil receipts are being handled by the United States. If the U.S. is to avoid the mistakes that followed the fall of Saddam Hussein, attending to the needs of the populace and paying the rank and file of the military should be priorities.

The Trump administration should also move as quickly as the security situation permits to reopen the U.S. embassy in Caracas. There is reporting out of Colombia that the U.S. Charge in Bogota has already made a trip to Caracas to evaluate the situation. This is a good thing. There is no substitute for on-the-ground engagement and observation.

The Cipher Brief is committed to publishing a range of perspectives on national security issues submitted by deeply experienced national security professionals. Opinions expressed are those of the author and do not represent the views or opinions of The Cipher Brief.

Have a perspective to share based on your experience in the national security field? Send it to Editor@thecipherbrief.com for publication consideration.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief, because national security is everyone’s business.

Maduro and Noriega: Assessing the Analogies

Asked if there were any restraints on his global powers, [President Trump] answered: “Yeah, there is one thing. My own morality. My own mind. It’s the only thing that can stop me.”

“I don’t need international law."

EXPERT PERSPECTIVE — Nicholas Maduro’s fate seems sealed: he will stand trial for numerous violations of federal criminal long-arm statutes and very likely spend decades as an inmate in the Federal Bureau of Prisons.

How this U.S. military operation that resulted in his apprehension is legally characterized has and will continue to be a topic of debate and controversy. Central to this debate have been two critically significant international law issues. First, was the operation conducted to apprehend him a violation of the Charter of the United Nations? Second, did that operation trigger applicability of the law of armed conflict?

The Trump administration has invoked the memory of General Manuel Noriega’s apprehension following the 1989 U.S. invasion of Panama, Operation Just Cause, in support of its assertion that the raid into Venezuela must be understood as nothing more than a law enforcement operation. But this reflects an invalid conflation between a law enforcement objective with a law enforcement operation.

Suggesting Operation Just Cause supports the assertion that this raid was anything other than an international armed conflict reflects a patently false analogy. Nonetheless, if - contrary to the President’s dismissal of international law quoted above – international law still means something for the United States - what happened in Panama and to General Noriega after his capture does have precedential value, so long as it is properly understood.

Parallels with the Noriega case?

Maduro was taken into U.S. custody 36 years to the day after General Manuel Noriega was taken into U.S. custody in Panama. Like Maduro, Noriega was the de facto leader of his nation. Like Maduro, the U.S. did not consider him the legitimate leader of his country due to his actions that led to nullifying a resounding election defeat of his hand-picked presidential candidate by an opposition candidate (in Panama’s case, Guillermo Endara).

Like Maduro, Noriega was under federal criminal indictment for narco-trafficking offenses. Like Maduro, that indictment had been pending several years. Like Maduro, Noriega was the commander of his nation’s military forces (in his case, the Panamanian Defense Forces, or PDF).

Like Maduro, his apprehension was the outcome of a U.S. military attack. Like Maduro, once he was captured, he was immediately transferred to the custody of U.S. law enforcement personnel and transported to the United States for his first appearance as a criminal defendant. And now we know that Maduro, like Noriega, immediately demanded prisoner of war status and immediate repatriation.

It is therefore unsurprising that commentators – and government officials – immediately began to offer analogies between the two to help understand both the legal basis for the raid into Venezuela and how Maduro was captured will impact his criminal case. Like how the Panama Canal itself cut that country into two, it is almost as if these two categories of analogy can be cut into valid and invalid.

Need a daily dose of reality on national and global security issues? Subscribe to The Cipher Brief’s Nightcap newsletter, delivering expert insights on today’s events – right to your inbox. Sign up for free today.

False Analogy to Operation Just Cause

Almost immediately following the news of the raid, critics – including me – began to question how the U.S. action could be credibly justified under international law?

As two of the most respected experts on use of force law – Michael Schmitt and Ryan Goodman - explained, there did not seem to be any valid legal justification for this U.S. military attack against another sovereign nation, even conceding the ends were arguably laudable.

My expectation was that the Trump administration would extend its ‘drug boat campaign’ rationale to justify its projection of military force into Venezuela proper; that self-defense justified U.S. military action to apprehend the leader of an alleged drug cartel that the Secretary of State had designated a Foreign Terrorist Organization. While I shared the view of almost all experts who have condemned this theory of legality, it seemed to be the only plausible rationale the government might offer.

It appears I may have been wrong. While no official legal opinion is yet available, statements by the Secretary of State and other officials seem to point to a different rationale: that this was not an armed attack but was instead a law enforcement apprehension operation.

And, as could be expected, Operation Just Cause – the military assault on Panama that led to General Noriega’s apprehension – is cited as precedent in support of this assertion. This effort to justify the raid is, in my view, even more implausible than even the drug boat self-defense theory.

At its core, it conflates a law enforcement objective with a law enforcement operation. Yes, it does appear that the objective of the raid was to apprehend an indicted fugitive. But the objective – or motive – for an operation does not dictate its legal characterization.

In this case, a military attack was launched to achieve that objective. Indeed, when General Caine took the podium in Mara Lago to brief the world on the operation, he emphasized how U.S. ‘targeting’ complied with principles of the law of armed conflict. Targeting, diversionary attacks, and engagement of enemy personnel leading to substantial casualties are not aspects of a law enforcement operation even if there is a law enforcement objective.

Nor does the example of Panama support this effort at slight of hand. The United States never pretended that the invasion of Panama was anything other than an armed conflict. Nor was apprehension of General Noriega an asserted legal justification for the invasion. Instead, as noted in this Government Accounting Office report,

The Department of State provided essentially three legal bases for the US. military action in Panama: the United States had exercised its legitimate right of self-defense as defined in the UN and CM charters, the United States had the right to protect and defend the Panama Canal under the Panama Canal Treaty, and U.S. actions were taken with the consent of the legitimate government of Panama

The more complicated issue in Panama was the nature of the armed conflict, with the U.S. asserting that it was ‘non-international’ due to the invitation from Guillermo Endara who the U.S. arranged to be sworn in as President on a U.S. base in Panama immediately prior to the attack. But while apprehending Noriega was almost certainly an operational objective for Just Cause, that in no way influenced the legal characterization of the operation.

International law

The assertion that a law enforcement objective provided the international legal justification for the invasion is, as noted above, contradicted by post-invasion analysis. It is also contradicted by the fact that the United States had ample opportunity to conduct a military operation to capture General Noriega during the nearly two years between the unsealing of his indictment and the invasion. This included the opportunity to provide modest military support to two coup attempts that would have certainly sealed Noriega’s fate.

With approximately 15,000 U.S. forces stationed within a few miles of his Commandancia, and his other office located on Fort Amador – a base shared with U.S. forces – had arrest been the primary U.S. objective it would have almost certainly happened much sooner and without a full scale invasion.

That invasion was justified to protect the approximate 30,000 U.S. nationals living in Panama. The interpretation of the international legal justification of self-defense to protect nationals from imminent deadly threats was consistent with longstanding U.S. practice.

Normally this would be effectuated by conducting a non-combatant evacuation operation. But evacuating such a substantial population of U.S. nationals was never a feasible option and assembling so many people in evacuation points – assuming they could get there safely – would have just facilitated PDF violence against them.

No analogous justification supported the raid into Venezuela. Criminal drug traffickers deserve no sympathy, and the harmful impact of illegal narcotics should not be diminished.

But President Bush confronted incidents of violence against U.S. nationals that appeared to be escalating rapidly and deviated from the norm of relatively non-violent harassment that had been ongoing for almost two years (I was one of the victims of that harassment, spending a long boring day in a Panamanian jail cell for the offense of wearing my uniform on my drive from Panama City to work).

With PDF infantry barracks literally a golf fairway across from U.S. family housing, it was reasonable to conclude the PDF needed to be neutered. Yet even this asserted legal basis for the invasion was widely condemned as invalid.

Noriega was ultimately apprehended and brought to justice. But that objective was never asserted as the principal legal basis for the invasion. Nor did it need to be. Operation Just Cause was, in my opinion (which concededly is influenced from my experience living in Panama for 3.5 years leading up to the invasion) a valid exercise of the inherent right of self-defense (also bolstered by the Canal Treaty right to defend the function of the Canal).

Nor was the peripheral law enforcement objective conflated with the nature of the operation. Operation Just Cause, like the raid into Venezuela, was an armed conflict. And, like the capture of Maduro, that leads to a valid aspect of analogy: Maduro’s status.

Like Noriega, at his initial appearance in federal court Maduro asserted his is a prisoner of war. And for good reason: the U.S. raid was an international armed conflict bringing into force the Third Geneva Convention, and Maduro by Venezuelan law was the military commander of their armed forces.

The U.S. government’s position on this assertion has not been fully revealed (or perhaps even formulated). But the persistent emphasis that the raid was a law enforcement operation that was merely facilitated by military action seems to be pointing towards a rejection. As in the case of General Noriega, this is both invalid and unnecessary: what matters is not what the government calls the operation, but the objective facts related to the raid.

Are you Subscribed to The Cipher Brief’s Digital Channel on YouTube? If not, you're missing out on insights so good they should require a security clearance.

Existence of an armed conflict

Almost immediately following news of the raid, the Trump administration asserted it was not a military operation, but instead a law enforcement operation supported by military action. This was the central premise of the statement made at the Security Council by Mike Waltz, the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations. Notably, Ambassador Waltz stated that, “As Secretary Rubio has said, there is no war against Venezuela or its people. We are not occupying a country. This was a law enforcement operation in furtherance of lawful indictments that have existed for decades.”

This characterization appears to be intended to disavow any assertion the operation qualified as an armed conflict within the meaning of common Article 2 of the four Geneva Conventions of 1949. That article indicates that the Conventions (and by extension the law of armed conflict generally) comes into force whenever there is an armed conflict between High Contracting Parties – which today means between any two sovereign states as these treaties have been universally adopted. It is beyond dispute that this article was intended to ensure application of the law of armed conflict would be dictated by the de facto existence of armed conflict, and not limited to de jure situations of war.

This pragmatic fact-based trigger for the law’s applicability was perhaps the most significant development of the law when the Conventions were revised between 1947 and 1949. It was intended to prevent states from disavowing applicability of the law through rhetorical ‘law-avoidance’ characterizations of such armed conflicts. While originally only impacting applicability of the four Conventions, this ‘law trigger’ evolved into a bedrock principle of international law: the law of armed conflict applies to any international armed conflict, meaning any dispute between states resulting in hostilities between armed forces, irrespective of how a state characterizes the situation.

By any objective assessment, the hostilities that occurred between U.S. and Venezuelan armed forces earlier this week qualified as an international armed conflict. Unfortunately, the U.S. position appears to be conflating a law enforcement objective with the assessment of armed conflict. And, ironically, this conflation appears to be premised on a prior armed conflict that doesn’t support the law enforcement operation assertion, but actually contradicts it: Operation Just Cause.

Judge Advocates have been taught for decades that the existence of an armed conflict is based on an objective assessment of facts; that the term was deliberately adopted to ensure the de facto situation dictated applicability of the law of armed conflict and to prevent what might best be understood as ‘creative obligation avoidance’ by using characterizations that are inconsistent with objective facts.

And when those objective facts indicate hostilities between the armed forces of two states, the armed conflict in international in nature, no matter how brief the engagement. This is all summarized in paragraph 3.4.2 of The Department of Defense Law of War Manual, which provides:

Act-Based Test for Applying Jus in Bello Rules. Jus in bello rules apply when parties are actually conducting hostilities, even if the war is not declared or if the state of war is not recognized by them. The de facto existence of an armed conflict is sufficient to trigger obligations for the conduct of hostilities. The United States has interpreted “armed conflict” in Common Article 2 of the 1949 Geneva Conventions to include “any situation in which there is hostile action between the armed forces of two parties, regardless of the duration, intensity or scope of the fighting.”

No matter what the objective of the Venezuelan raid may have been, there undeniable indication that the situation involved, “hostile action between” U.S. and Venezuelan armed forces.

This was an international armed conflict within the meaning of Common Article 2 of the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 – the definitive test for assessing when the law of armed conflict comes into force. To paraphrase Judge Hoeveler, ‘[H]owever the government wishes to label it, what occurred in [Venezuela] was clearly an "armed conflict" within the meaning of Article 2. Armed troops intervened in a conflict between two parties to the treaty.’ Labels are not controlling, facts are. We can say the sun is the moon, but it doesn’t make it so.

Prisoner of war status

So, like General Noriega, Maduro seems to have a valid claim to prisoner of war status (Venezuelan law designated him as the military commander of their armed forces authorizing him to wear the rank of a five-star general). And like the court that presided over Noriega’s case, the court presiding over Maduro’s case qualifies as a ‘competent tribunal’ within the meaning of Article 5 of the Third Convention to make that determination.

But will it really matter? The answer will be the same as it was for Noriega: not that much. Most notably, it will have no impact on the two most significant issues related to his apprehension: first, whether he is entitled to immediate repatriation because hostilities between the U.S. and Venezuela have apparently ended, and 2. Whether he is immune from prosecution for his pre-conflict alleged criminal misconduct.

Article 118 of the Third Convention indicates that, “Prisoners of war shall be released and repatriated without delay after the cessation of active hostilities.” However, this repatriation obligation is qualified. Article 85 specifically acknowledges that, “[P]risoners of war prosecuted under the laws of the Detaining Power for acts committed prior to capture . . .”

Article 119 provides, “Prisoners of war against whom criminal proceedings for an indictable offence are pending may be detained until the end of such proceedings, and, if necessary, until the completion of the punishment. The same shall apply to prisoners of war already convicted for an indictable offence.”

This means that like General Noriega, extending prisoner of war status to Maduro will in no way impede the authority of the United States to prosecute him for his pre-conflict indicted offenses. Nor would it invalidate the jurisdiction of a federal civilian court, as Article 84 also provides that,

A prisoner of war shall be tried only by a military court, unless the existing laws of the Detaining Power expressly permit the civil courts to try a member of the armed forces of the Detaining Power in respect of the particular offence alleged to have been committed by the prisoner of war.” As in General Noriega’s case, because U.S. service-members would be subject to federal civilian jurisdiction for the same offenses, Maduro is also subject to that jurisdiction.

This would obviously be different if he were charged with offenses arising out of the brief hostilities the night of the raid, in which case his status would justify a claim of combatant immunity, a customary international law concept that protects privileged belligerents from being subjected to criminal prosecution by a detaining power for lawful conduct related to the armed conflict (and implicitly implemented by Article 87 of the Third Convention). But there is no such relationship between the indicted offenses and the hostilities that resulted in Maduro’s capture.

Prisoner of war status will require extending certain rights and privileges to Maduro during his trial and, assuming his is convicted, during his incarceration. Notice to a Protecting Power, ensuring certain procedural rights, access to the International Committee of the Red Cross during incarceration, access to care packages, access to communications, and perhaps most notably segregation from the general inmate population.

Perhaps he will end up in the same facility where the government incarcerated Noriega, something I saw first-hand when I visited him in 2004. A separate building in the federal prison outside Miami was converted as his private prison; his uniform – from an Army no longer in existence – hung on the wall; the logbook showed family and ICRC visits.

Concluding thoughts

The government should learn a lesson from Noriega’s experience: concede the existence of an international armed conflict resulted in Maduro’s capture and no resist a claim of prisoner of war status. There is little reason to resist this seemingly obvious consequence of the operation.

Persisting in the assertion that the conflation of a law enforcement objective with a law enforcement operation as a way of denying the obvious – that this was an international armed conflict – jeopardizes U.S. personnel who in the future might face the unfortunate reality of being captured in a raid like this.

Indeed, it is not hard to imagine how aggressively the U.S. would be insisting on prisoner of war status had any of the intrepid forces who executed this mission been captured by Venezuela.

There is just no credible reason why aversion to acknowledging this reality should increase the risk that some unfortunate day in the future it is one of our own who is subjected to a ‘perp walk’ as a criminal by a detaining power that is emboldened to deny the protection of the Third Convention.

The Cipher Brief is committed to publishing a range of perspectives on national security issues submitted by deeply experienced national security professionals. Opinions expressed are those of the author and do not represent the views or opinions of The Cipher Brief.

Have a perspective to share based on your experience in the national security field? Send it to Editor@thecipherbrief.com for publication consideration.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief, because national security is everyone’s business.

After Maduro’s Removal, the U.S. Faces Its Hardest Test Yet in Venezuela

THE WEEKEND INTERVIEW — As Venezuela faces a moment of profound uncertainty following a dramatic U.S. operation that removed longtime strongman Nicolás Maduro from power, policymakers and intelligence professionals are grappling with what comes next for a country long plagued by authoritarian rule, with Washington signaling an unprecedented level of involvement in shaping Venezuela’s political future.

To help unpack what's ahead, Cipher Brief CEO Suzanne Kelly spoke with former CIA Senior Executive David Fitzgerald, a veteran intelligence officer whose career spans decades of operational, leadership, and policy roles across Latin America. Drawing on firsthand experience as a former Chief of Station and senior headquarters official overseeing the region, Fitzgerald offers a sobering assessment of Venezuela’s challenges, from rebuilding its institutions and oil sector to managing internal security threats while navigating the competing interests of China, Russia, Cuba, and Iran. The conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

David Fitzgerald

A 37-yr. CIA veteran, David Fitgerald retired in 2021 as Chief of Station in a Middle Eastern country, which hosted CIA’s largest field station. As a seven-time Chief of Station, Fitzgerald served in numerous conflict zones to include Africa, Latin America, the Middle East and South Asia. He also held senior HQS positions that included Latin America Chief of Operations and Latin America Deputy Division Chief. He also served as the senior DCIA representative at U.S. Military’s Central Command from 2017-2020, where he participated in several tier 1 operations as the intelligence advisor to the commander.

The Cipher Brief: How are you looking at Venezuela at this moment through a national security lens? What do you see as the next real challenge the U.S. is likely to face there?

Fitzgerald: As President Trump has said, the U.S. intends to run Venezuela. I'm still waiting for how the U.S. government intends to define 'running Venezuela'. I'm going to assume, and I hate to assume, but I'll assume that the goal will be to work closely with the current Venezuelan government to transition to a democracy and allow elections, something like that. So that will just be my assumption in lieu of any comments or any guidelines coming out of the White House.

The Cipher Brief: You understand the history, the politics, the culture of Venezuela better than most Americans. Where do you think some of the bumps in the road will come as the U.S. tries to figure out and define, as you put it, what running Venezuela really means?

Fitzgerald: It's a very diverse country. It's an incredibly rich resource country. People talk about the oil and the petroleum, but it's not only that. It could be one of the largest gold producers in the world. It's amazing the amount of natural resources that Venezuela has, yet 25 years after President Chávez was elected as president, it's one of the poorest countries in Latin America.

I think one of the hurdles that they're going to have is the brain drain. You don't have a strong cadre. A great example is Pedevesa, [Petróleos de Venezuela], the state run oil company. Back in the 90's, Pedevesa was considered one of the most efficient and best run oil companies in the world. Compared to even the private companies, it was a machine because they owned everything from downstream to upstream. They owned the drilling, they owned the pipelines, they owned the refineries, they owned the oil tankers, they owned the refineries in the U.S., they owned the distribution through their Citco company here. It was just an amazing company, and it was always held up as a model for state run companies. Of course, with the election of President Hugo Chávez, and then in 2002, the general strike when he just fired all of the Pedevesa members - even today, if you look around at the Chevrons, Exxons, the BPs, you'll find a large amount of former Pedevesa employees because they all migrated to the private petroleum companies because they were that good.

So, one of the biggest challenges is that Venezuela's going to need the financial means to really rebuild itself. I was last in Venezuela in 2013, and I'd been there in the early '90s, and it looked exactly the same. The infrastructure was terrible. Nothing had been modernized or built. So instead, what the Maduro and the Chavez government had done, was basically used Pedevesa as their cash cow to really distribute that money to themselves, steal the money, or distribute it to their followers. There was no effort to modernize the infrastructure or to do the necessary maintenance in the oil fields. That's why I think they're producing maybe 10% to 15% of the amount of oil they were at their peak.

So for me, that's really the key. How do you get Pedevesa up and running so it becomes a profitable company again that can actually provide the necessary resources for the country to rebuild itself?

Need a daily dose of reality on national and global security issues? Subscribe to The Cipher Brief’s Nightcap newsletter, delivering expert insights on today’s events – right to your inbox. Sign up for free today.

The Cipher Brief: If you were looking into your crystal ball, and you had to guess, will there be enough political stability with the U.S. involvement to be able to allow for this infrastructure to be rebuilt? How difficult is that political component going to be?

Fitzgerald: I think it's twofold. Not only the political component, but the security component. How do you transition from basically a dictatorship to some form of transparent democracy, which I think is the White House's goal. You do that via Delcy Rodríguez and the current Venezuelan government. As you know, the PSUV, which is the United Socialist Party of Venezuela, which is Maduro's party, they control every apparatus of government, whether it's the Supreme Court, the judicial branch, the legislative branch, the executive branch, it's owned by them. There is no transparency right now. How do you get away from that? How do you rebuild these institutions so they become functional again and in some type of democratic transparent manner? That has to be a principal goal.

Number two, the security situation. You have maybe 20% to 25% of the population supporting Maduro and the PSUV. I would argue most of these people are supporting the party because they benefit from the party. They're either on the payrolls, they have some type of sweetheart deal, or they're able to conduct their illegal activities. The security forces are not hardcore ideologues. I think with the death of Chávez in 2013, he was the last ideologue you had as far as the Bolivarian revolution. My experience working with these people is that they're just in it for their own self-enrichment. Nobody really drank the Kool-Aid and said, "I want to be a Bolivarian revolutionary." I mean, this might have happened during the earlier stages when Chávez was first elected, but through the decades, it's become just an empty suit. Nobody really believes in any type of revolution.

On the security side, getting back to that, you have a disruptive element. You have this organization called the Colectivos, which is kind of a non-official goon squad that is supported by the government, basically comprised of criminals and local bullies. During demonstrations, they're the ones who go out there and start beating people and stuff like that. But you have the security services themselves as well. The rank and file. I think if you can do something like we did maybe in the Haiti occupation and in Panama where we actually formed an interim security force — I can't talk about the Haitian National Police nowadays as an effective force — but at the time in 1994, they became an effective enough security force, which provided security to the populace. That led the whole population to believe that there was hope.

I think that's going to be key along with the political transition. Can you provide security? Can you provide faith that people will adhere to the rules and regulations? How you do that? It's a good question.

Venezuela's a little different than most Latin countries. There is no national police force, other than the National Guard, which currently, if you talk to our DEA colleagues they'd probably say it's one of the largest drug cartels on the continent right now. Like the United States, Venezuela is divided into the state and municipal police forces.

For example, Caracas has two major police forces. You have the city of Caracas Police Force, and then you have the Miranda State Police Force, which is about maybe a third of Caracas, and then the rest is by the city of Caracas. Then you go out to the different states in Venezuela. They each have their own police force, and the large cities all have their police force. Years ago, they tried to form this Bolivarian national police agency. We're trying to incorporate this. It's never really worked because these police forces are all influenced and run by the local politicians.

So, that could work to our advantage as far as being able to work independently of the government and work with these local institutions to not only enhance their capability, but kind of vet them, cleanse them.

The Cipher Brief: How do you think Russia and China are assessing what''s next in Venezuela? What are the losses here and what are the opportunities here for each of them?

Fitzgerald: Let's talk about China first because that's probably going to be the most important for Venezuela. China must be extremely careful about how they handle this because they have literally billions and billions of dollars in loans that they provided the Bolivarian government. And one of their concerns, no doubt is that if you have a new democratic government, they could come in and say, "You know something? These loans that you signed with China, we don't consider them valid. We think they're illegal, and we're going to nullify all the loans." And right now, China's getting paid back in petroleum. So, China's got to be worried.

That means that if you're China, you're going to make nice with any new government because you don't want to be in a situation where they just say, "We consider these agreements you made with former government officials as illegal, and we will no longer honor them." So I don't see China being a spoiler. I see them willing to work with any new government coming into power because they have a lot of financial stake in what happens in Venezuela.

Russia, on the other hand, has very little commerce here. Russia's main trade with Venezuela is in arms. Venezuela's never even been able to pay back the loans or the purchases they made on some of the weapons systems they bought. Iran's another one. Iran's been there for decades now. It's entrenched. They've been allowed to work pretty much without limits in Venezuela, going back to, I think it was 2012, and the assassination attempt on the Saudi Ambassador in Washington. That was all being run out of, or being facilitated by, the Iranian embassy in Caracas.

So, it's going to affect all of their relationships. Iran's been more important than they realize for their oil industry as far as providing the parts and the 'know how' to maintain the oil fields and some of their refineries. A lot of that's coming from Iran. The big thing here that people don't realize is that there's one ingredient that's important for Venezuelan petroleum and if you don't have this, you really can't produce the amount of petroleum you need. Even at today's rate, you can't produce it. So Iran's been a major provider of this substance.

Are you Subscribed to The Cipher Brief’s Digital Channel on YouTube? Insights so good, they should require a security clearance.

The Cipher Brief: How are drug cartels likely looking at this? And what about Cuba?

Fitzgerald: I would love to be in Cuba right now and listen to what they're saying about this. I mean, this really must be a shocker for them. Number one, for their security service. They just had a major failure because it's very well known that all of President Maduro's inner security was being provided by the Cubans. They're the only people he trusted. To a greater extent, they're out of security. Plus all their security services were being managed by the Cuban CI officers. The Cubans don't do it for free. So Venezuela pays the tab for that, and no doubt it's a greatly enhanced bill that they were getting from the Cuban government for President Maduro's security.

On the other end, as you know, Suzanne, the petroleum is just as vital to the Cuban economy. It's not all of it, but it's a major percentage of the petroleum that Cuba uses to include refined products that are provided by Venezuela at incredibly reduced rates that Venezuela knows Cuba will never repay. So, they have billions of dollars in debts to Venezuela and although they're technically selling the petroleum to Cuba, there's pretty much an understanding that it's not going to be repaid. So that's going to be a big blow to Cuba right now.

The Cipher Brief: What are the indicators that you're going to be watching for next that give you some clue as to where things might be headed?

Fitzgerald: Well, my big indicator is what's the plan? I'm sure they're huddling together both in the IC and in the State Department and the White House trying to figure out, 'Okay, how can we transition the current government to some type of viable democratic government and allow for a free election?' And there's probably been a million plans thrown out there. They just haven't figured out which one they're going to use. So I think that's what I'm waiting for is what the administration intends to roll out as their plan and how they intend to run Venezuela.

I think one of the big things here as far as Venezuela goes, is how to actually rebuild the country. It's going to require the private sector. The U.S. government is not going to be some nation builder like we tried to do in Iraq. And the great thing is that Venezuela has the resources that are quite sought after in the world where I think you're going to get a lot of interest from the private sector.

For example, a friend of mine asked the other day about the construction that would be needed. You're going to see some of the major construction companies needed to go in there and just rebuild the cities and the streets and everything. It's just the infrastructure there that hasn't been really modernized or updated in decades. So I think there is going to be a lot of interest in that. I think that interest by the private sector will also encourage the government to become as transparent and as democratic as it can be. So look for that too. And it's just not all about oil — it's minerals, construction, and the electric grid - it's across the board.

The Cipher Brief is your place for expert-driven national security insights. Read more in The Cipher Brief because National Security is Everyone’s Business

CIA-affiliated plane spotted at Caracas airport

A CIA-linked LM-100J Super Hercules operated by Pallas Aviation landed in Caracas on January 10. The aircraft, using callsign WDE08 and tail number N96MG, departed shortly afterward and returned to Puerto Rico. The aircraft belongs to Pallas Aviation, described as a private company that performs “specialized work worldwide that most others refuse.” The company operates […]

A CIA-linked LM-100J Super Hercules operated by Pallas Aviation landed in Caracas on January 10. The aircraft, using callsign WDE08 and tail number N96MG, departed shortly afterward and returned to Puerto Rico. The aircraft belongs to Pallas Aviation, described as a private company that performs “specialized work worldwide that most others refuse.” The company operates […] U.S. Forces use Growlers to blind Venezuelan air-defense systems

United States forces used Navy EA-18G Growler electronic attack aircraft during the January 3 strike on Venezuela, employing high-power jamming to disable multiple layers of the country’s air-defense network. The action was first acknowledged through statements from Venezuelan military personnel who reported that radar systems “were blinded” minutes before precision weapons struck their sites. According […]

United States forces used Navy EA-18G Growler electronic attack aircraft during the January 3 strike on Venezuela, employing high-power jamming to disable multiple layers of the country’s air-defense network. The action was first acknowledged through statements from Venezuelan military personnel who reported that radar systems “were blinded” minutes before precision weapons struck their sites. According […] U.S. Navy launches MQ-4C Triton on Caribbean spy mission

A United States Navy MQ-4C Triton long-range intelligence aircraft conducted an extended surveillance mission over the Caribbean Sea on 8 January after departing Naval Station Mayport, according to publicly available flight-tracking data. The aircraft, identified as MQ-4C Triton number 169659 and flying under the callsign BLKCAT6, operated for roughly ten hours in international airspace north […]

A United States Navy MQ-4C Triton long-range intelligence aircraft conducted an extended surveillance mission over the Caribbean Sea on 8 January after departing Naval Station Mayport, according to publicly available flight-tracking data. The aircraft, identified as MQ-4C Triton number 169659 and flying under the callsign BLKCAT6, operated for roughly ten hours in international airspace north […] U.S. Forces use AGM-154C-1 glide bomb in Venezuela strike

United States forces conducted a strike in Venezuela on January 3 using the AGM-154C-1 Joint Stand-Off Weapon, after local authorities released images showing debris from the precision-guided glide munition at one of the impact sites. According to photographs published by Venezuelan officials, identifiable fragments of an AGM-154C-1 were found after the January 3 attack. The […]

United States forces conducted a strike in Venezuela on January 3 using the AGM-154C-1 Joint Stand-Off Weapon, after local authorities released images showing debris from the precision-guided glide munition at one of the impact sites. According to photographs published by Venezuelan officials, identifiable fragments of an AGM-154C-1 were found after the January 3 attack. The […] U.S. forces secure Russia-flagged oil tanker

U.S. European Command has confirmed that U.S. agencies, supported by the U.S. Department of War, seized the Russia-flagged crude-oil tanker Marinera — formerly Bella 1 — in the North Atlantic following a federal warrant issued for violations of U.S. sanctions. According to a statement from U.S. European Command, the operation was carried out by the […]

U.S. European Command has confirmed that U.S. agencies, supported by the U.S. Department of War, seized the Russia-flagged crude-oil tanker Marinera — formerly Bella 1 — in the North Atlantic following a federal warrant issued for violations of U.S. sanctions. According to a statement from U.S. European Command, the operation was carried out by the […] The U.S. Says it Will “Run” Venezuela. What Will That Mean?

DEEP DIVE – As audacious and complex as it was for the U.S. to extract Nicolas Maduro from Venezuela – and to do so without a single U.S. casualty – the challenges ahead may be even harder. “We’re gonna run it,” President Donald Trump said Saturday, referring to a post-Maduro Venezuela. The president gave few details and no specific time frame, saying only that the U.S. would “run the country” until a “safe, proper and judicious transition” could be arranged. U.S. oil companies would return to Venezuela, investing “billions and billions” of dollars to reboot the oil sector and the country’s economy. American “boots on the ground” might be deployed in the interim.

It was a remarkable series of statements from a president who has criticized past American nation-building projects, and it raised questions about how exactly the Trump Administration would “run” a country beset by profound challenges. Venezuela, a country twice the size of Iraq, has endured decades of authoritarian rule, corruption, drug-related violence, and economic pain. And for the moment at least, the country’s leader still pledges allegiance to Maduro.

Miguel Tinker Salas, a Venezuelan historian, Professor Emeritus at Pomona College and Fellow at the Quincy Institute, said that when Trump spoke those words – “we’re gonna run it” – he was stunned.

“Initially, my jaw dropped,” Salas told The Cipher Brief. “Even at the height of U.S. influence in Venezuela, in the 1950s, 60s and 70s, they never said they wanted to run the country. And I don't think the Trump administration comprehends the complexity that they're dealing with for a country as diverse and as big as Venezuela.”

Even those who cheered the U.S. military operation warned of the difficulties that lie ahead. Former National Security Adviser John Bolton, who pronounced himself “delighted” by Maduro’s ouster, told NewsNation the mission was “maybe step one of a much longer process. Maduro is gone but the regime is still in place.”