The Artemis 2 Astronauts Will Observe Parts of the Moon Humans Have Never Laid Eyes On

5 min read

As NASA’s X-59 quiet supersonic research aircraft continues a series of flight tests over the California high desert in 2026, its pilot will be flying with a buddy closely looking out for his safety.

That colleague will be another test pilot in a separate chase aircraft. His job as chase pilot: keep a careful watch on things as he tracks the X-59 through the sky, providing an extra set of eyes to help ensure the flight tests are as safe as possible.

Having a chase pilot watch to make sure operations are going smoothly is an essential task when an experimental aircraft is exercising its capabilities for the first time. The chase pilot also takes on tasks like monitoring local weather and supplementing communications between the X-59 and air traffic control.

“All this helps reduce the test pilot’s workload so he can concentrate on the actual test mission,” said Jim “Clue” Less, a NASA research pilot since 2010 and 21-year veteran U.S. Air Force flyer.

Less served as chase pilot in a NASA F/A-18 research jet when NASA test pilot Nils Larson made the X-59’s first flight on Oct. 28. Going forward, Less and Larson will take turns flying as X-59 test pilot or chase pilot.

So how close does a chase aircraft fly to the X-59?

“We fly as close as we need to,” Less said. “But no closer than we need to.”

The distance depends on where the chase aircraft needs to be to best ensure the success of the test flight. Chase pilots, however, never get so close as to jeopardize safety.

Jim "clue" LESS

NASA Test Pilot

For example, during the X-59’s first flight the chase aircraft moved to within a wingspan of the experimental aircraft. At that proximity, the airspeed and altitude indicators inside both aircraft could be compared, allowing the X-59 team to calibrate their instruments.

Generally, the chase aircraft will remain about 500 and 1,000 feet away—or about 5-10 times the length of the X-59 itself—as the two aircraft cruise together.

“Of course, the chase pilot can move in closer if I need to look over something on the aircraft,” Less said. “We would come in as close as needed, but for the most part the goal is to stay out of the way.”

The up-close-and-personal vantage point of the chase aircraft also affords the opportunity to capture photos and video of the test aircraft.

For the initial X-59 flight, a NASA photographer—fully trained and certified to fly in a high-performance jet—sat in the chase aircraft’s rear seat to record images and transmit high-definition video down to the ground.

“We really have the best views,” Less said. “The top focus of the test team always is a safe flight and landing. But if we get some great shots in the process, it’s an added bonus.”

Chase aircraft can also carry sensors that gather data during the flight that would be impossible to obtain from the ground. In a future phase of X-59 flights, the chase aircraft will carry a probe to measure the X-59’s supersonic shock waves and help validate that the airplane is producing a quieter sonic “thump,” rather than a loud sonic boom to people on the ground.

The instrumentation was successfully tested using a pair of NASA F-15 research jets earlier this year.

As part of NASA’s Quesst mission, the data could help open the way for commercial faster-than-sound air travel over land.

Chase aircraft have served as a staple of civilian and military flight tests for decades, with NASA and its predecessor—the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics—employing aircraft of all types for the job.

Today, at NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California, two different types of research aircraft are available to serve as chase for X-59 flights: NASA-operated F/A-18 Hornets and F-15 Eagles.

While both types are qualified as chase aircraft for the X-59, each has characteristics that make them appropriate for certain tasks.

The F/A-18 is a little more agile flying at lower speeds. One of NASA’s F/A-18s has a two-seat cockpit, and the optical quality and field of view of its canopy makes it the preferred aircraft for Armstrong’s in-flight photographers.

At the same time, the F-15 is more capable of keeping pace with the X-59 during supersonic test flights and carries the instrumentation that will measure the X-59’s shock waves.

“The choice for which chase aircraft we will use for any given X-59 test flight could go either way depending on other mission needs and if any scheduled maintenance requires the airplane to be grounded for a while,” Less said.

Jim Banke is a veteran aviation and aerospace communicator with more than 40 years of experience as a writer, producer, consultant, and project manager based at Cape Canaveral, Florida. He is part of NASA Aeronautics' Strategic Communications Team and is Managing Editor for the Aeronautics topic on the NASA website.

Manus is adding app publishing that aims to turn a described app into an installable mobile build, handling packaging while you finish distribution in Google Play Console or App Store Connect and TestFlight.

The post You can publish apps from Manus without Xcode or Android Studio appeared first on Digital Trends.

KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, Florida—Preparations for the first human spaceflight to the Moon in more than 50 years took a big step forward this weekend with the rollout of the Artemis II rocket to its launch pad.

The rocket reached a top speed of just 1 mph on the four-mile, 12-hour journey from the Vehicle Assembly Building to Launch Complex 39B at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. At the end of its nearly 10-day tour through cislunar space, the Orion capsule on top of the rocket will exceed 25,000 mph as it plunges into the atmosphere to bring its four-person crew back to Earth.

"This is the start of a very long journey," said NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman. "We ended our last human exploration of the moon on Apollo 17."

© Stephen Clark/Ars Technica

KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, Florida—The rocket NASA is preparing for sending four astronauts on a trip around the Moon will emerge from its assembly building on Florida's Space Coast early Saturday for a slow crawl to its seaside launch pad.

Riding atop one of NASA's diesel-powered crawler transporters, the Space Launch System rocket and its mobile launch platform will exit the Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy Space Center around 7:00 am EST (11:00 UTC). The massive tracked transporter, certified by Guinness as the world's heaviest self-propelled vehicle, is expected to cover the four miles between the assembly building and Launch Complex 39B in about eight to 10 hours.

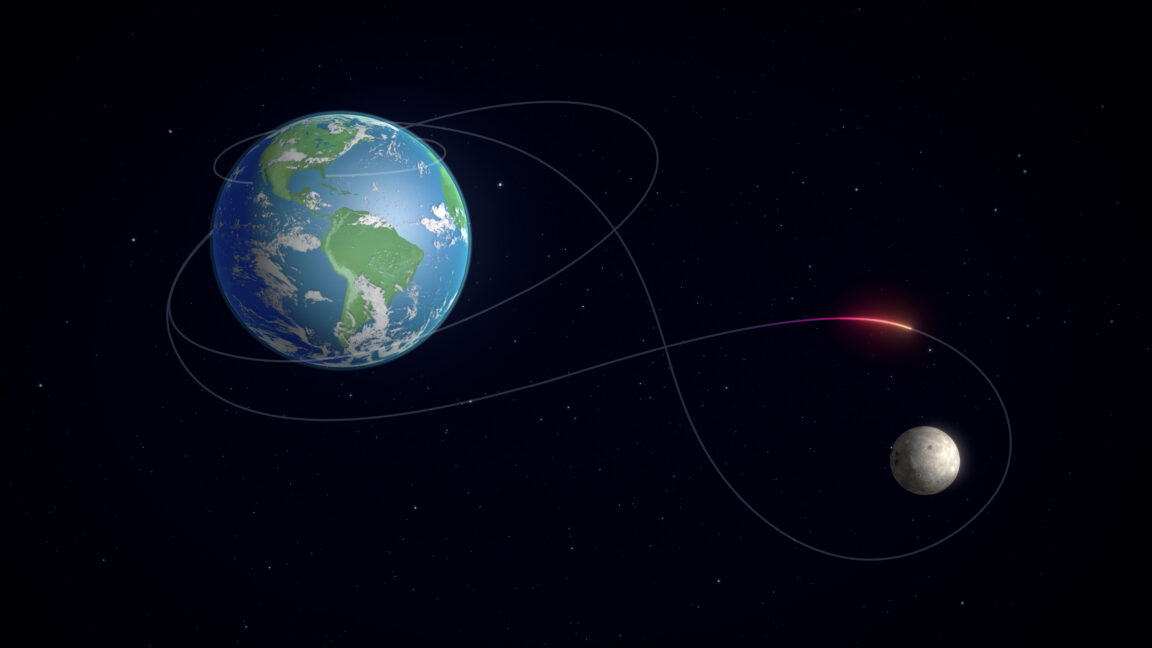

The rollout marks a major step for NASA's Artemis II mission, the first human voyage to the vicinity of the Moon since the last Apollo lunar landing in December 1972. Artemis II will not land. Instead, a crew of four astronauts will travel around the far side of the Moon at a distance of several thousand miles, setting the record for the farthest humans have ever ventured from Earth.

© NASA

3 min read

Two retired U.S. Air Force F-15 jets have joined the flight research fleet at NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California, transitioning from military service to a new role enabling breakthrough advancements in aerospace.

The F-15s will support supersonic flight research for NASA’s Flight Demonstrations and Capabilities project, including testing for the Quesst mission’s X-59 quiet supersonic research aircraft. One of the aircraft will return to the air as an active NASA research aircraft. The second will be used for parts to support long-term fleet sustainment.

“These two aircraft will enable successful data collection and chase plane capabilities for the X-59 through the life of the Low Boom Flight Demonstrator project” said Troy Asher, director for flight operations at NASA Armstrong. “They will also enable us to resume operations with various external partners, including the Department of War and commercial aviation companies.”

The aircraft came from the Oregon Air National Guard’s 173rd Fighter Wing at Kingsley Field. After completing their final flights with the Air Force, the two aircraft arrived at NASA Armstrong Dec. 22, 2025.

“NASA has been flying F-15s since some of the earliest models came out in the early 1970s,” Asher said. “Dozens of scientific experiments have been flown over the decades on NASA’s F-15s and have made a significant contribution to aeronautics and high-speed flight research.”

The F-15s allow NASA to operate in high-speed, high-altitude flight-testing environments. The aircraft can carry experimental hardware externally – under its wings or slung under the center – and can be modified to support flight research.

Now that these aircraft have joined NASA’s fleet, the team at Armstrong can modify their software, systems, and flight controls to suit mission needs. The F-15’s ground clearance allows researchers to install instruments and experiments that would not fit beneath many other aircraft.

NASA has already been operating two F-15s modified so their pilots can operate safely at up to 60,000 feet, the top of the flight envelop for the X-59, which will cruise at 55,000 feet. The new F-15 that will fly for NASA will receive the same modification, allowing for operations at altitudes most standard aircraft cannot reach. The combination of capability, capacity, and adaptability makes the F-15s uniquely suited for flight research at NASA Armstrong.

“The priority is for them to successfully support the X-59 through completion of that mission,” Asher said. “And over the longer term, these aircraft will help position NASA to continue supporting advanced aeronautics research and partnerships.”

Two Americans, a Japanese astronaut, and a Russian cosmonaut returned to Earth early Thursday after 167 days in orbit, cutting short their stay on the International Space Station by more than a month after one of the crew members encountered an unspecified medical issue last week.

The early homecoming culminated in an on-target splashdown in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of San Diego at 12:41 am PST (08:41 UTC) inside a SpaceX Crew Dragon spacecraft. The splashdown occurred minutes after the Dragon capsule streaked through the atmosphere along the California coastline, with sightings of Dragon's fiery trail reported from San Francisco to Los Angeles.

Four parachutes opened to slow the capsule for the final descent. Zena Cardman, NASA's commander of the Crew-11 mission, radioed SpaceX mission control moments after splashdown: "It feels good to be home, with deep gratitude to the teams who got us there and back."

© NASA/Bill Ingalls

Welcome back, aspiring cyberwarriors!

We are really glad to see you back for the second part of this series. In the first article, we explored some of the cheapest and most accessible ways to build your own hacking drone. We looked at practical deployment problems, discussed how difficult stable control can be, and even built small helper scripts to make your life easier. That was your first step into this subject where drones become independent cyber platforms instead of just flying gadgets.

We came to the conclusion that the best way to manage our drone would be via 4G. Currently, in 2026, Russia is adapting a new strategy in which it is switching to 4G to control drones. An example of this is the family of Shahed drones. These drones are generally built as long-range, loitering attack platforms that use pre-programmed navigation systems, and initially they relied only on satellite guidance to reach their targets rather than on a constant 4G data link. However, in some reported variants, cellular connectivity was used to support telemetry and control-related functionality.

In recent years, Russia has been observed modifying these drones to carry different types of payloads and weapons, including missiles and MANPADS (Man-Portable Air-Defense System) mounted onto the airframe. The same principle applies here as with other drones. Once you are no longer restricted to a short-range Wi-Fi control link and move to longer-range communication options, your main limitation becomes power. In other words, the energy source ultimately defines how long the aircraft can stay in the air.

Today, we will go further. In this part, we are going to remove the smartphone from the back of the drone to reduce weight. The free space will instead be used for chipsets and antennas.

In the previous part, you may have asked yourself why an attacker would try to remotely connect to a drone through its obvious control interfaces, such as Wi-Fi. Why not simply connect directly to the flight controller and bypass the standard communication layers altogether? In the world of consumer-ready drones, you will quickly meet the same obstacle over and over again. These drones usually run closed proprietary control protocols. Before you can talk to them directly, you first need to reverse engineer how everything works, which is neither simple nor fast.

However, there is another world of open-source drone-control platforms. These include projects such as Betaflight, iNav, and Ardupilot. The simplest of these, Betaflight, supports direct control-motor command transmission over UART. If you have ever worked with microcontrollers, UART will feel familiar. The beauty here is that once a drone listens over UART, it can be controlled by almost any small Linux single-board computer. All you need to do is connect a 4G module and configure a VPN, and suddenly you have a controllable airborne hacking robot that is reachable from anywhere with mobile coverage. Working with open systems really is a pleasure because nothing is truly hidden.

So, what does the hacker need? The first requirement is a tiny and lightweight single-board computer, paired with a compact 4G modem. A very convenient combination is the NanoPi Neo Air together with the Sim7600G module. Both are extremely small and almost the same size, which makes mounting easier.

The NanoPi communicates with the 4G modem over UART. It actually has three UART interfaces. One UART can be used exclusively for Internet connectivity, and another one can be used for controlling the drone flight controller. The pin layout looks complicated at first, but once you understand which UART maps to which pins, the wiring becomes straightforward.

After some careful soldering, the finished 4G control module will look like this:

Even very simple flight controllers usually support at least two UART ports. One of these is normally already connected to the drone’s traditional radio receiver, while the second one remains available. This second UART can be connected to the NanoPi. The wiring process is exactly the same as adding a normal RC receiver.

The advantage of this approach is flexibility. You can seamlessly switch between control modes through software settings rather than physically rewiring connectors. You attach the NanoPi and Sim7600G, connect the cable, configure the protocol, and the drone now supports 4G-based remote control.

Depending on your drone’s layout, the board can be mounted under the frame, inside the body, or even inside 3D-printed brackets. Once the hardware is complete, it is time to move into software. The NanoPi is convenient because, when powered, it exposes a USB-based console. You do not even need a monitor. Just run a terminal such as:

nanoPi > minicom -D /dev/ttyACM0 -b 9600

Then disable services that you do not need:

nanoPi > systemctl disable wpa_supplicant.service

nanoPi > systemctl disable NetworkManager.service

Enable the correct UART interfaces with:

nanoPi > armbian-config

From the System menu you go to Hardware and enable UART1 and UART2, then reboot.

Next, install your toolkit:

nanoPi > apt install minicom openvpn python3-pip cvlc

Minicom is useful for quickly checking UART traffic. For example, check modem communication like this:

minicom -D /dev/ttyS1 -b 115200

ATIf all is well, then you need to config files for the modem. The first one goes to /etc/ppp/peers/telecom. Replace “telecom” with the name of the cellular provider you are going to use to establish 4G connection.

And the second one goes to /etc/chatscripts/gprs

To activate 4G connectivity, you can run:

nanoPi > pon telecom

Once you confirm connectivity using ping, you should enable automatic startup using the interfaces file. Open /etc/network/interfaces and add these lines:

auto telecom

iface telecom inet ppp

provider telecomNow comes the logical connectivity layer. To ensure you can always reach the drone securely, connect it to a central VPN server:

nanoPi > cp your_vds.ovpn /etc/openvpn/client/vds.conf

nanoPi > systemctl enable openvpn-client@vds

This allows your drone to “phone home” every time it powers on.

Next, you must control the drone motors. Flight controllers speak many logical control languages, but with UART the easiest option is the MSP protocol. We install a Python library for working with it:

NanoPi > cd /opt/; git clone https://github.com/alduxvm/pyMultiWii

NanoPi > pip3 install pyserial

The protocol is quite simple, and the library itself only requires knowing the port number. The NanoPi is connected to the drone’s flight controller via UART2, which corresponds to the ttyS2 port. Once you have the port, you can start sending values for the main channels: roll, propeller RPM/throttle, and so on, as well as auxiliary channels:

Find the script on our GitHub and place the it in ~/src/ named as control.py

The NanoPi uses UART2 for drone communication, which maps to ttyS2. You send MSP commands containing throttle, pitch, roll, yaw, and auxiliary values. An important detail is that the flight controller expects constant updates. Even if the drone is idle on the ground, neutral values must continue to be transmitted. If this stops, the controller assumes communication loss. The flight controller must also be told that MSP data is coming through UART2. In Betaflight Configurator you assign UART2 to MSP mode.

We are switching the active UART for the receiver (the NanoPi is connected to UART2 on the flight controller, while the stock receiver is connected to UART1). Next we go to Connection and select MSP as the control protocol.

If configured properly, you now have a drone that you can control over unlimited distance as long as mobile coverage exists and your battery holds out. For video streaming, connect a DVP camera to the NanoPi and stream using VLC like this:

cvlc v4l2:///dev/video0:chroma=h264:width=800:height= \

--sout '#transcode{vcodec=h264,acodec=mp3,samplerate=44100}:std{access=http,mux=ffmpeg{mux=flv},dst=0.0.0.0:8080}' -vvv

The live feed becomes available at:

http://drone:8080/Here “drone” is the VPN IP address of the NanoPi.

To make piloting practical, you still need a control interface. One method is to use a real transmitter such as EdgeTX acting as a HID device. Another approach is to create a small JavaScript web app that reads keyboard or touchscreen input and sends commands via WebSockets. If you prefer Ardupilot, there are even ready-made control stacks.

By now, your drone is more than a toy. It is a remotely accessible cyber platform operating anywhere there is mobile coverage.

Previously we discussed how buildings and range limitations affect RF-based drone control. With mobile-controlled drones, cellular towers actually become allies instead of obstacles. However, drones can face anti-drone jammers. Most jammers block the 2.4 GHz band, because many consumer drones use this range. Higher end jammers also attack 800-900 MHz and 2.4 GHz used by RC systems like TBS, ELRS, and FRSKY. The most common method though is GPS jamming and spoofing. Spoofing lets an attacker broadcast fake satellite signals so the drone believes false coordinates. Since drone communication links are normally encrypted, GPS becomes the weak point. That means a cautious attacker may prefer to disable GPS completely. Luckily, on many open systems such as Betaflight drones or FPV cinewhoops, GPS is optional. Indoor drones usually do not use GPS anyway.

As for mobile-controlled drones, jamming becomes significantly more difficult. To cut the drone off completely, the defender must jam all relevant 4G, 3G, and 2G bands across multiple frequencies. If 4G is jammed, the modem falls back to 3G. If 3G goes down, it falls back to 2G. This layering makes mobile-controlled drones surprisingly resilient. Of course, extremely powerful directional RF weapons exist that wipe out all local radio communication when aimed precisely. But these tools are expensive and require high accuracy.

We transformed the drone into a fully independent device capable of long-range remote operation via mobile networks. The smartphone was replaced with a NanoPi Neo Air and a Sim7600G 4G modem, routed UART communication directly into the flight controller, and configured MSP-based command delivery. We also explored VPN connectivity, video streaming, and modern control interfaces ranging from RC transmitters to browser-based tools. Open-source flight controllers give us incredible flexibility.

In Part 3, we will build the attacking part and carry out our first wireless attack.

If you like the work we’re doing here and want to take your skills even further, we also offer a full SDR for Hackers Career Path. It’s a structured training program designed to guide you from the fundamentals of Software-Defined Radio all the way to advanced, real-world applications in cybersecurity and signals intelligence.