Assessing SIEM effectiveness

A SIEM is a complex system offering broad and flexible threat detection capabilities. Due to its complexity, its effectiveness heavily depends on how it is configured and what data sources are connected to it. A one-time SIEM setup during implementation is not enough: both the organization’s infrastructure and attackers’ techniques evolve over time. To operate effectively, the SIEM system must reflect the current state of affairs.

We provide customers with services to assess SIEM effectiveness, helping to identify issues and offering options for system optimization. In this article, we examine typical SIEM operational pitfalls and how to address them. For each case, we also include methods for independent verification.

This material is based on an assessment of Kaspersky SIEM effectiveness; therefore, all specific examples, commands, and field names are taken from that solution. However, the assessment methodology, issues we identified, and ways to enhance system effectiveness can easily be extrapolated to any other SIEM.

Methodology for assessing SIEM effectiveness

The primary audience for the effectiveness assessment report comprises the SIEM support and operation teams within an organization. The main goal is to analyze how well the usage of SIEM aligns with its objectives. Consequently, the scope of checks can vary depending on the stated goals. A standard assessment is conducted across the following areas:

- Composition and scope of connected data sources

- Coverage of data sources

- Data flows from existing sources

- Correctness of data normalization

- Detection logic operability

- Detection logic accuracy

- Detection logic coverage

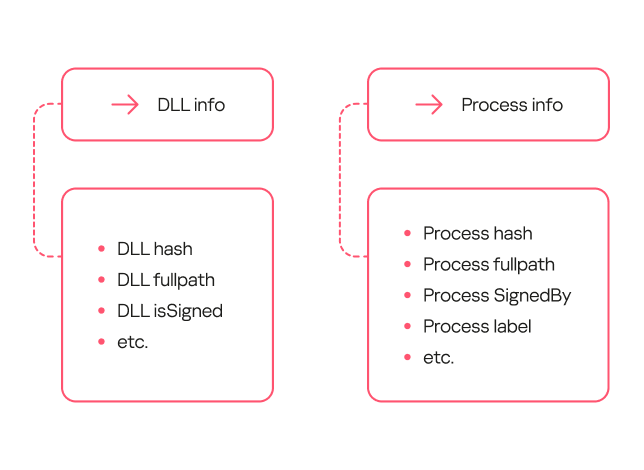

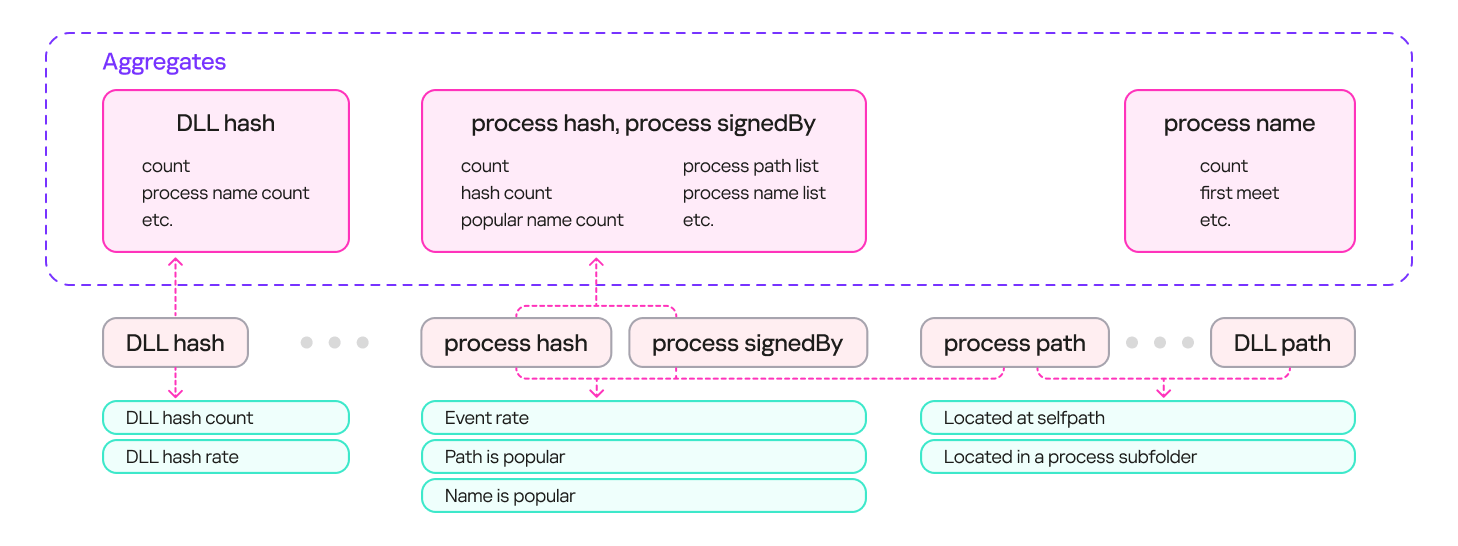

- Use of contextual data

- SIEM technical integration into SOC processes

- SOC analysts’ handling of alerts in the SIEM

- Forwarding of alerts, security event data, and incident information to other systems

- Deployment architecture and documentation

At the same time, these areas are examined not only in isolation but also in terms of their potential influence on one another. Here are a couple of examples illustrating this interdependence:

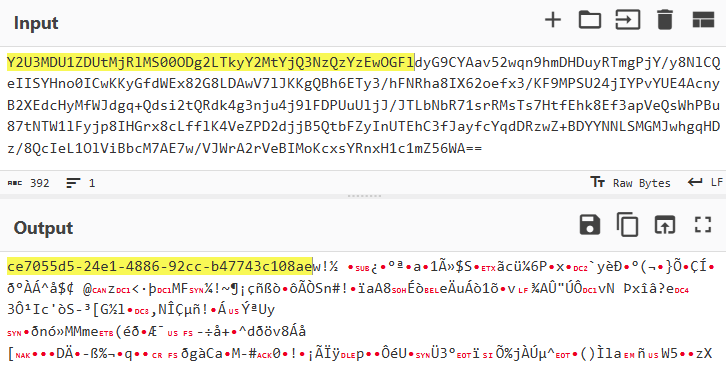

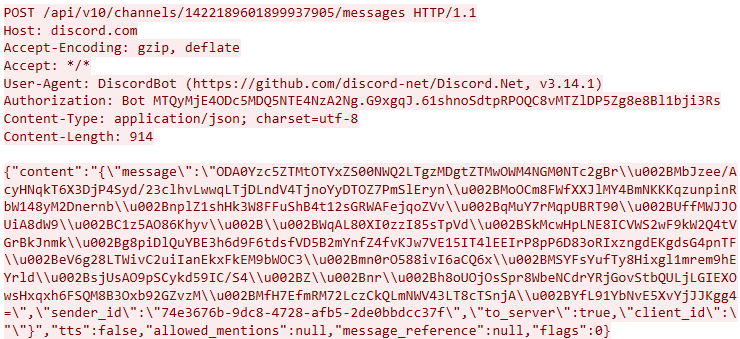

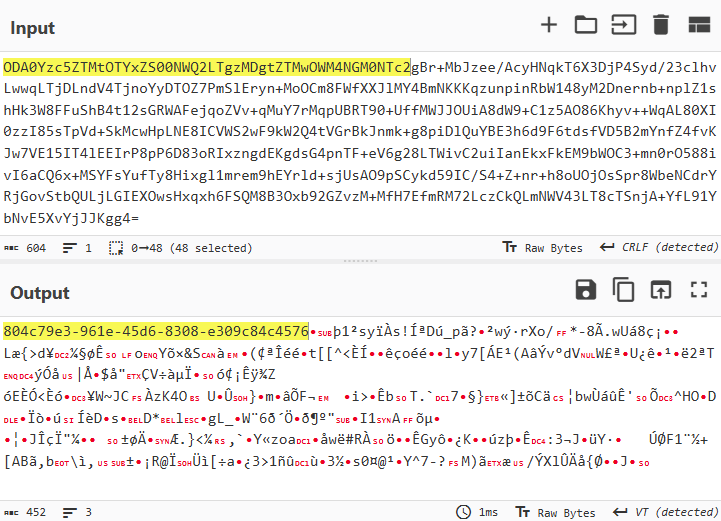

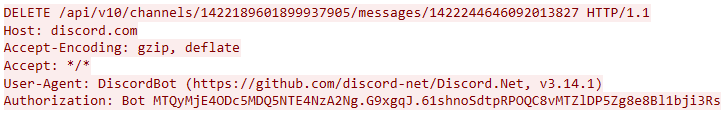

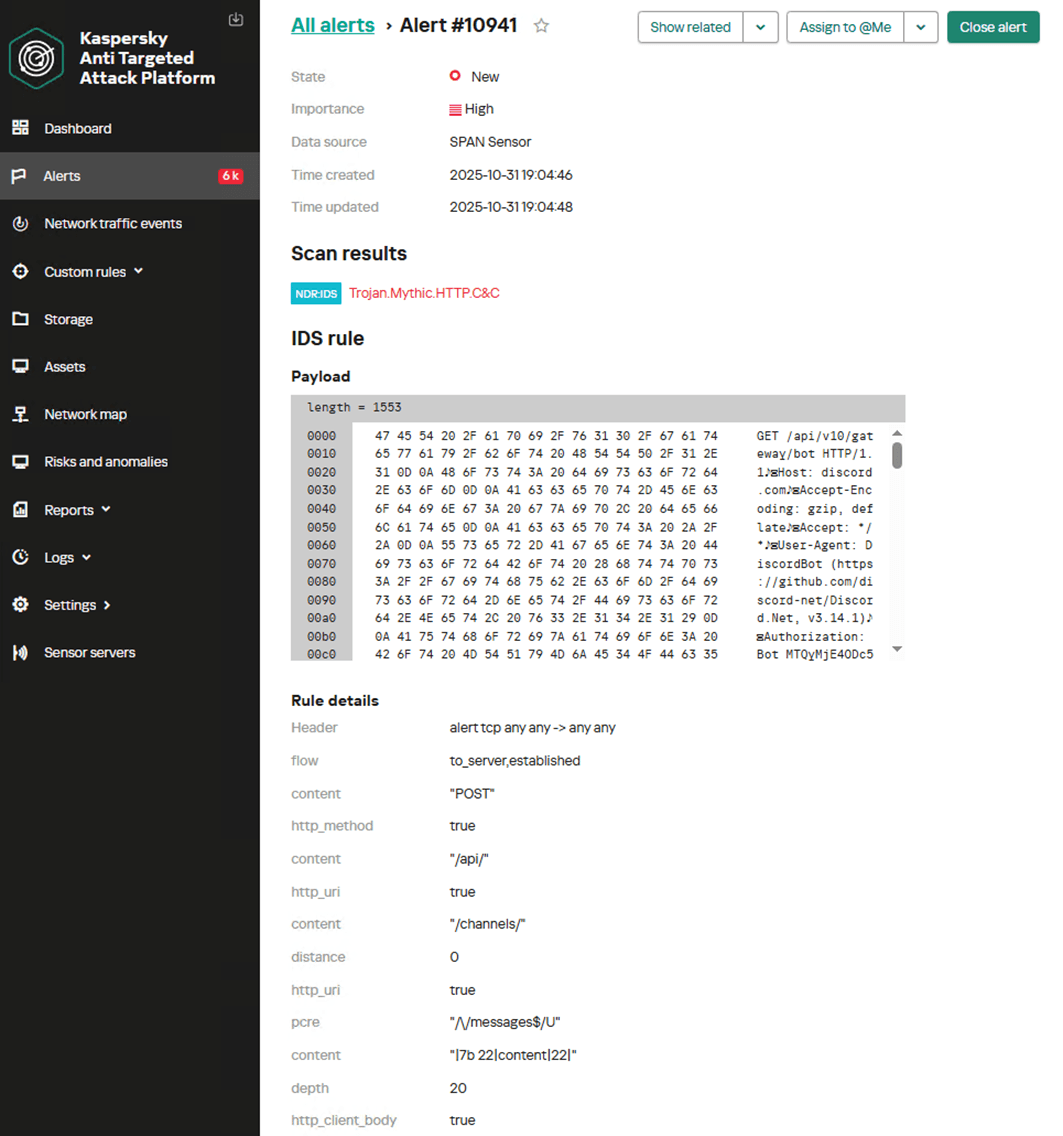

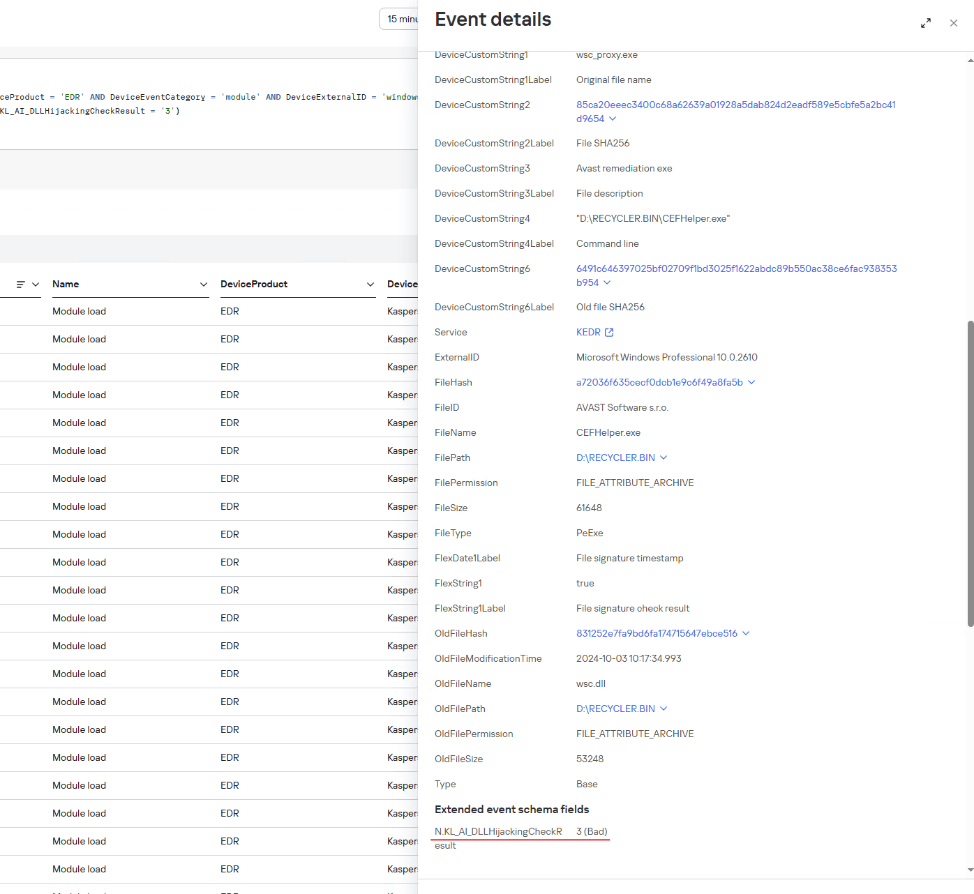

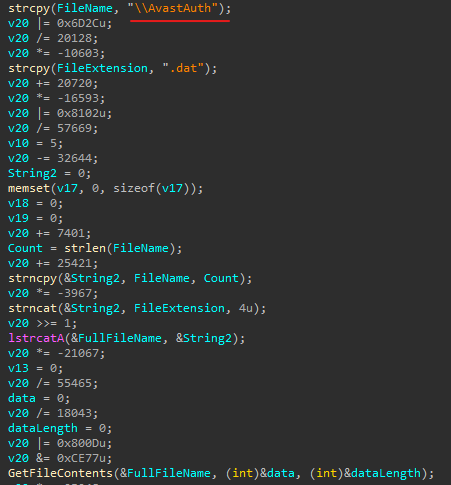

- Issues with detection logic due to incorrect data normalization. A correlation rule with the condition

deviceCustomString1 not contains <string>triggers a large number of alerts. The detection logic itself is correct: the specific event and the specific field it targets should not generate a large volume of data matching the condition. Our review revealed the issue was in the data ingested by the SIEM, where incorrect encoding caused the string targeted by the rule to be transformed into a different one. Consequently, all events matched the condition and generated alerts. - When analyzing coverage for a specific source type, we discovered that the SIEM was only monitoring 5% of all such sources deployed in the infrastructure. However, extending that coverage would increase system load and storage requirements. Therefore, besides connecting additional sources, it would be necessary to scale resources for specific modules (storage, collectors, or the correlator).

The effectiveness assessment consists of several stages:

- Collect and analyze documentation, if available. This allows assessing SIEM objectives, implementation settings (ideally, the deployment settings at the time of the assessment), associated processes, and so on.

- Interview system engineers, analysts, and administrators. This allows assessing current tasks and the most pressing issues, as well as determining exactly how the SIEM is being operated. Interviews are typically broken down into two phases: an introductory interview, conducted at project start to gather general information, and a follow-up interview, conducted mid-project to discuss questions arising from the analysis of previously collected data.

- Gather information within the SIEM and then analyze it. This is the most extensive part of the assessment, during which Kaspersky experts are granted read-only access to the system or a part of it to collect factual data on its configuration, detection logic, data flows, and so on.

The assessment produces a list of recommendations. Some of these can be implemented almost immediately, while others require more comprehensive changes driven by process optimization or a transition to a more structured approach to system use.

Issues arising from SIEM operations

The problems we identify during a SIEM effectiveness assessment can be divided into three groups:

- Performance issues, meaning operational errors in various system components. These problems are typically resolved by technical support, but to prevent them, it is worth periodically checking system health status.

- Efficiency issues – when the system functions normally but seemingly adds little value or is not used to its full potential. This is usually due to the customer using the system capabilities in a limited way, incorrectly, or not as intended by the developer.

- Detection issues – when the SIEM is operational and continuously evolving according to defined processes and approaches, but alerts are mostly false positives, and the system misses incidents. For the most part, these problems are related to the approach taken in developing detection logic.

Key observations from the assessment

Event source inventory

When building the inventory of event sources for a SIEM, we follow the principle of layered monitoring: the system should have information about all detectable stages of an attack. This principle enables the detection of attacks even if individual malicious actions have gone unnoticed, and allows for retrospective reconstruction of the full attack chain, starting from the attackers’ point of entry.

Problem: During effectiveness assessments, we frequently find that the inventory of connected source types is not updated when the infrastructure changes. In some cases, it has not been updated since the initial SIEM deployment, which limits incident detection capabilities. Consequently, certain types of sources remain completely invisible to the system.

We have also encountered non-standard cases of incomplete source inventory. For example, an infrastructure contains hosts running both Windows and Linux, but monitoring is configured for only one family of operating systems.

How to detect: To identify the problems described above, determine the list of source types connected to the SIEM and compare it against what actually exists in the infrastructure. Identifying the presence of specific systems in the infrastructure requires an audit. However, this task is one of the most critical for many areas of cybersecurity, and we recommend running it on a periodic basis.

We have compiled a reference sheet of system types commonly found in most organizations. Depending on the organization type, infrastructure, and threat model, we may rearrange priorities. However, a good starting point is as follows:

- High Priority – sources associated with:

- Remote access provision

- External services accessible from the internet

- External perimeter

- Endpoint operating systems

- Information security tools

- Medium Priority – sources associated with:

- Remote access management within the perimeter

- Internal network communication

- Infrastructure availability

- Virtualization and cloud solutions

- Low Priority – sources associated with:

- Business applications

- Internal IT services

- Applications used by various specialized teams (HR, Development, PR, IT, and so on)

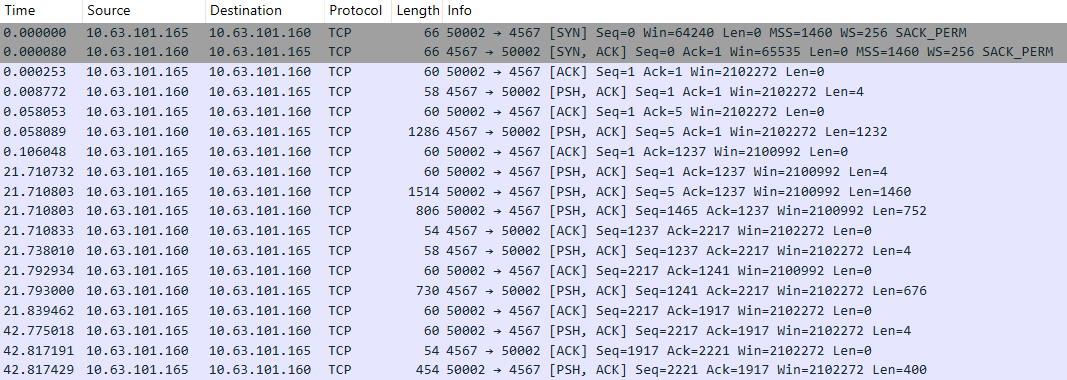

Monitoring data flow from sources

Regardless of how good the detection logic is, it cannot function without telemetry from the data sources.

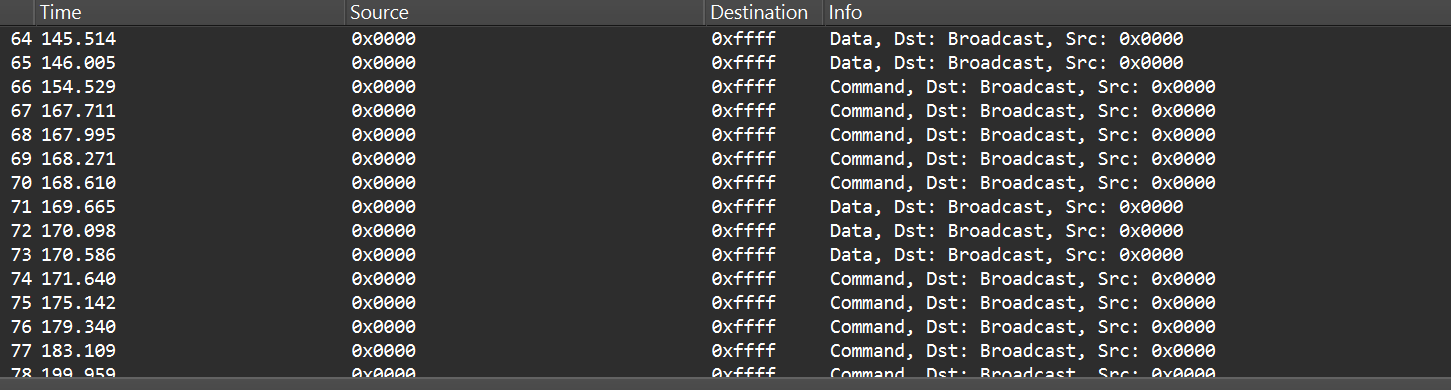

Problem: The SIEM core is not receiving events from specific sources or collectors. Based on all assessments conducted, the average proportion of collectors that are configured with sources but are not transmitting events is 38%. Correlation rules may exist for these sources, but they will, of course, never trigger. It is also important to remember that a single collector can serve hundreds of sources (such as workstations), so the loss of data flow from even one collector can mean losing monitoring visibility for a significant portion of the infrastructure.

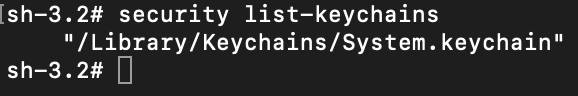

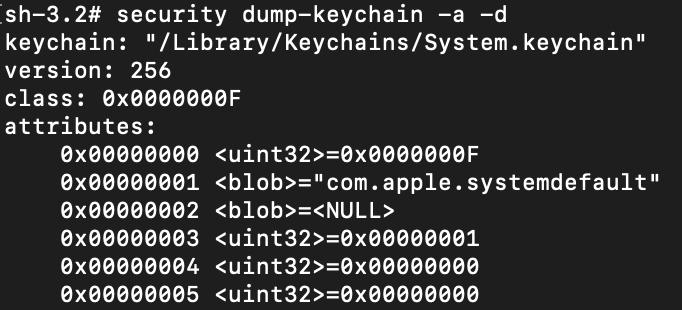

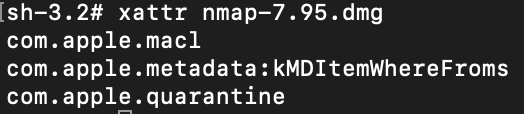

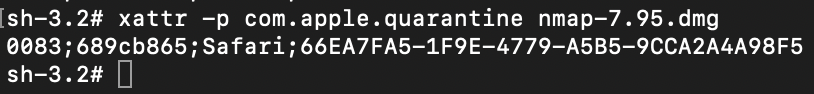

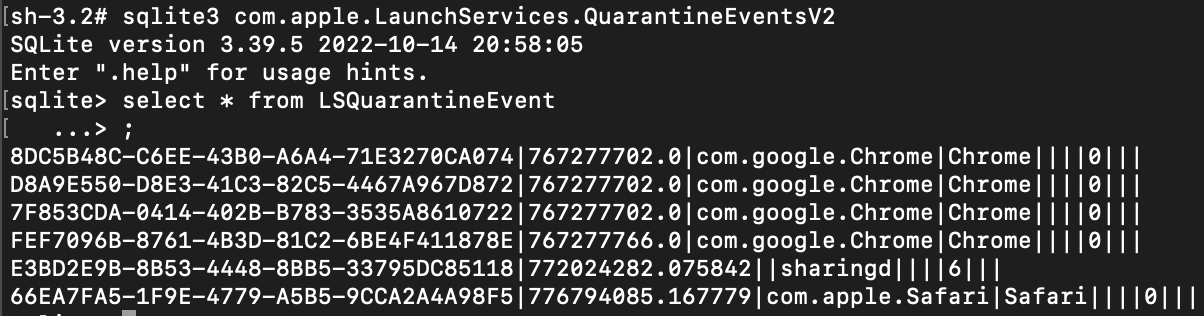

How to detect: The process of locating sources that are not transmitting data can be broken down into two components.

- Checking collector health. Find the status of collectors (see the support website for the steps to do this in Kaspersky SIEM) and identify those with a status of

Offline,Stopped,Disabled, and so on. - Checking the event flow. In Kaspersky SIEM, this can be done by gathering statistics using the following query (counting the number of events received from each collector over a specific time period):

SELECT count(ID), CollectorID, CollectorName FROM `events` GROUP BY CollectorID, CollectorName ORDER BY count(ID)It is essential to specify an optimal time range for collecting these statistics. Too large a range can increase the load on the SIEM, while too small a range may provide inaccurate information for a one-time check – especially for sources that transmit telemetry relatively infrequently, say, once a week. Therefore, it is advisable to choose a smaller time window, such as 2–4 days, but run several queries for different periods in the past.

Additionally, for a more comprehensive approach, it is recommended to use built-in functionality or custom logic implemented via correlation rules and lists to monitor event flow. This will help automate the process of detecting problems with sources.

Event source coverage

Problem: The system is not receiving events from all sources of a particular type that exist in the infrastructure. For example, the company uses workstations and servers running Windows. During SIEM deployment, workstations are immediately connected for monitoring, while the server segment is postponed for one reason or another. As a result, the SIEM receives events from Windows systems, the flow is normalized, and correlation rules work, but an incident in the unmonitored server segment would go unnoticed.

How to detect: Below are query variations that can be used to search for unconnected sources.

SELECT count(distinct, DeviceAddress), DeviceVendor, DeviceProduct FROMeventsGROUP BY DeviceVendor, DeviceProduct ORDER BY count(ID)SELECT count(distinct, DeviceHostName), DeviceVendor, DeviceProduct FROMeventsGROUP BY DeviceVendor, DeviceProduct ORDER BY count(ID)

We have split the query into two variations because, depending on the source and the DNS integration settings, some events may contain either a DeviceAddress or DeviceHostName field.

These queries will help determine the number of unique data sources sending logs of a specific type. This count must be compared against the actual number of sources of that type, obtained from the system owners.

Retaining raw data

Raw data can be useful for developing custom normalizers or for storing events not used in correlation that might be needed during incident investigation. However, careless use of this setting can cause significantly more harm than good.

Problem: Enabling the Keep raw event option effectively doubles the event size in the database, as it stores two copies: the original and the normalized version. This is particularly critical for high-volume collectors receiving events from sources like NetFlow, DNS, firewalls, and others. It is worth noting that this option is typically used for testing a normalizer but is often forgotten and left enabled after its configuration is complete.

How to detect: This option is applied at the normalizer level. Therefore, it is necessary to review all active normalizers and determine whether retaining raw data is required for their operation.

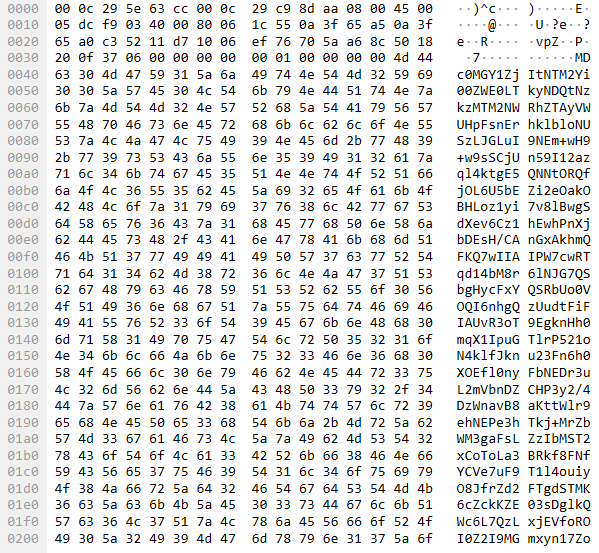

Normalization

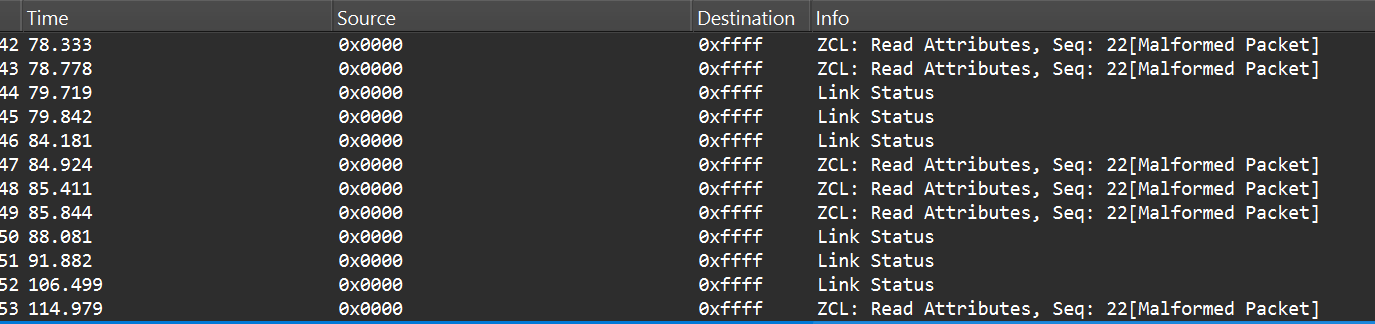

As with the absence of events from sources, normalization issues lead to detection logic failing, as this logic relies on finding specific information in a specific event field.

Problem: Several issues related to normalization can be identified:

- The event flow is not being normalized at all.

- Events are only partially normalized – this is particularly relevant for custom, non-out-of-the-box normalizers.

- The normalizer being used only parses headers, such as

syslog_headers, placing the entire event body into a single field, this field most often beingMessage. - An outdated default normalizer is being used.

How to detect: Identifying normalization issues is more challenging than spotting source problems due to the high volume of telemetry and variety of parsers. Here are several approaches to narrowing the search:

- First, check which normalizers supplied with the SIEM the organization uses and whether their versions are up to date. In our assessments, we frequently encounter auditd events being normalized by the outdated normalizer,

Linux audit and iptables syslog v2for Kaspersky SIEM. The new normalizer completely reworks and optimizes the normalization schema for events from this source. - Execute the query:

SELECT count(ID), DeviceProduct, DeviceVendor, CollectorName FROM `events` GROUP BY DeviceProduct, DeviceVendor, CollectorName ORDER BY count(ID)This query gathers statistics on events from each collector, broken down by the DeviceVendor and DeviceProduct fields. While these fields are not mandatory, they are present in almost any normalization schema. Therefore, their complete absence or empty values may indicate normalization issues. We recommend including these fields when developing custom normalizers.

To simplify the identification of normalization problems when developing custom normalizers, you can implement the following mechanism. For each successfully normalized event, add a Name field, populated from a constant or the event itself. For a final catch-all normalizer that processes all unparsed events, set the constant value: Name = unparsed event. This will later allow you to identify non-normalized events through a simple search on this field.

Detection logic coverage

Collected events alone are, in most cases, only useful for investigating an incident that has already been identified. For a SIEM to operate to its full potential, it requires detection logic to be developed to uncover probable security incidents.

Problem: The mean correlation rule coverage of sources, determined across all our assessments, is 43%. While this figure is only a ballpark figure – as different source types provide different information – to calculate it, we defined “coverage” as the presence of at least one correlation rule for a source. This means that for more than half of the connected sources, the SIEM is not actively detecting. Meanwhile, effort and SIEM resources are spent on connecting, maintaining, and configuring these sources. In some cases, this is formally justified, for instance, if logs are only needed for regulatory compliance. However, this is an exception rather than the rule.

We do not recommend solving this problem by simply not connecting sources to the SIEM. On the contrary, sources should be connected, but this should be done concurrently with the development of corresponding detection logic. Otherwise, it can be forgotten or postponed indefinitely, while the source pointlessly consumes system resources.

How to detect: This brings us back to auditing, a process that can be greatly aided by creating and maintaining a register of developed detection logic. Given that not every detection logic rule explicitly states the source type from which it expects telemetry, its description should be added to this register during the development phase.

If descriptions of the correlation rules are not available, you can refer to the following:

- The name of the detection logic. With a standardized approach to naming correlation rules, the name can indicate the associated source or at least provide a brief description of what it detects.

- The use of fields within the rules, such as

DeviceVendor,DeviceProduct(another argument for including these fields in the normalizer),Name,DeviceAction,DeviceEventCategory,DeviceEventClassID, and others. These can help identify the actual source.

Excessive alerts generated by the detection logic

One criterion for correlation rules effectiveness is a low false positive rate.

Problem: Detection logic generates an abnormally high number of alerts that are physically impossible to process, regardless of the size of the SOC team.

How to detect: First and foremost, detection logic should be tested during development and refined to achieve an acceptable false positive rate. However, even a well-tuned correlation rule can start producing excessive alerts due to changes in the event flow or connected infrastructure. To identify these rules, we recommend periodically running the following query:

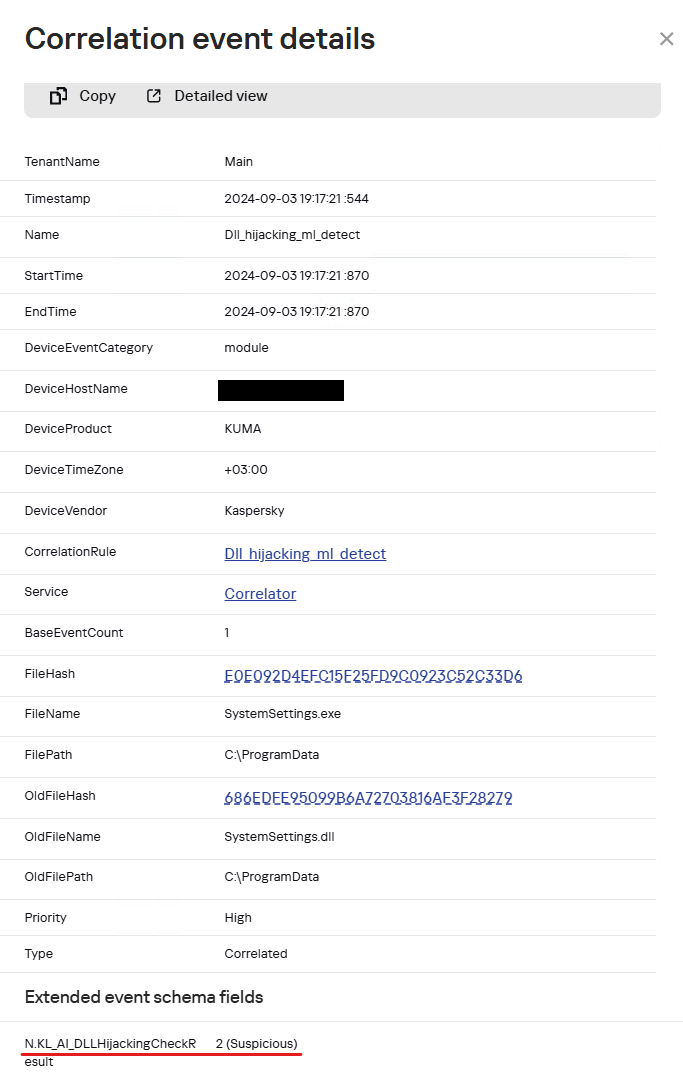

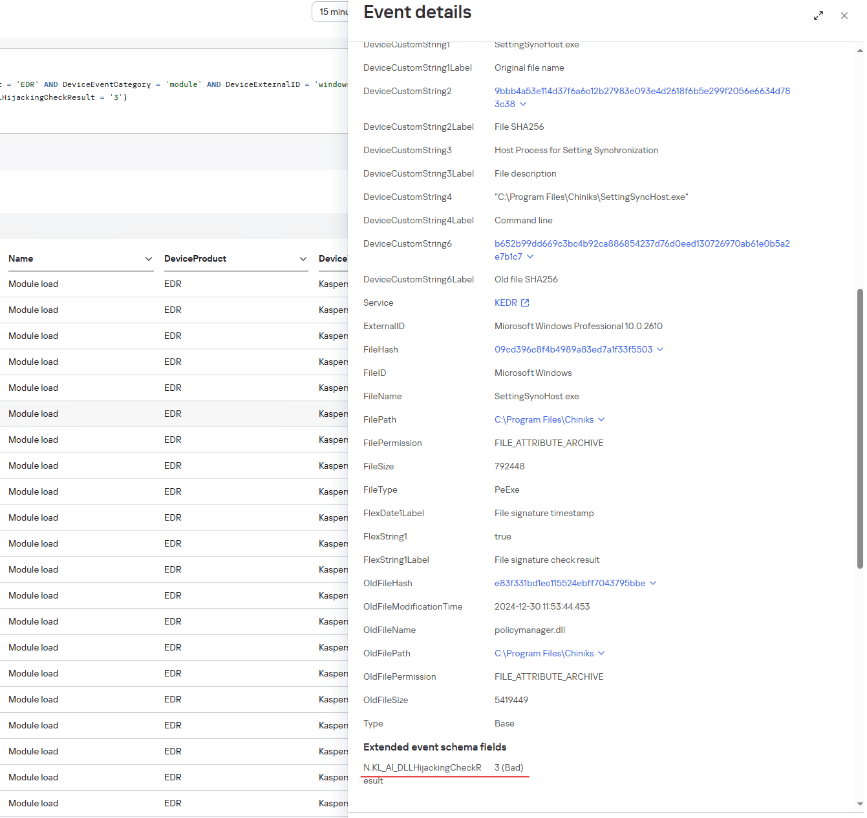

SELECT count(ID), Name FROM `events` WHERE Type = 3 GROUP BY Name ORDER BY count(ID)

In Kaspersky SIEM, a value of 3 in the Type field indicates a correlation event.

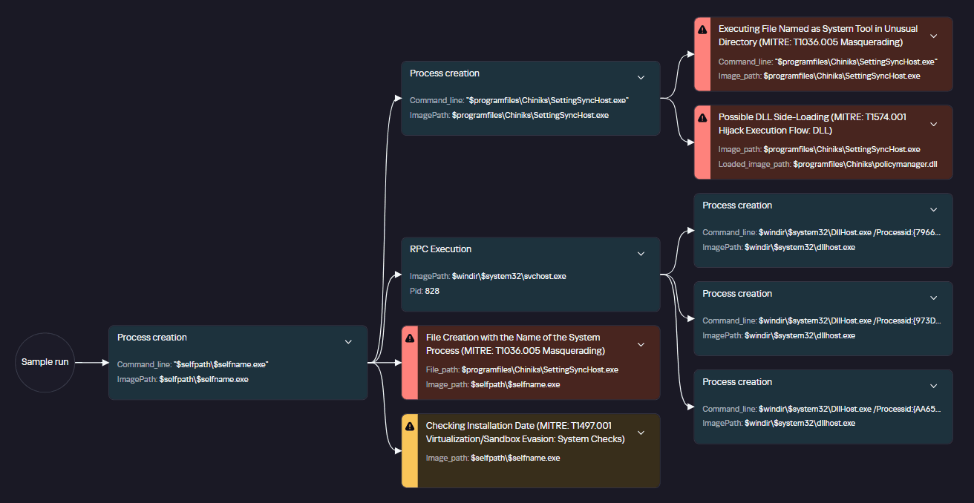

Subsequently, for each identified rule with an anomalous alert count, verify the correctness of the logic it uses and the integrity of the event stream on which it triggered.

Depending on the issue you identify, the solution may involve modifying the detection logic, adding exceptions (for example, it is often the case that 99% of the spam originates from just 1–5 specific objects, such as an IP address, a command parameter, or a URL), or adjusting event collection and normalization.

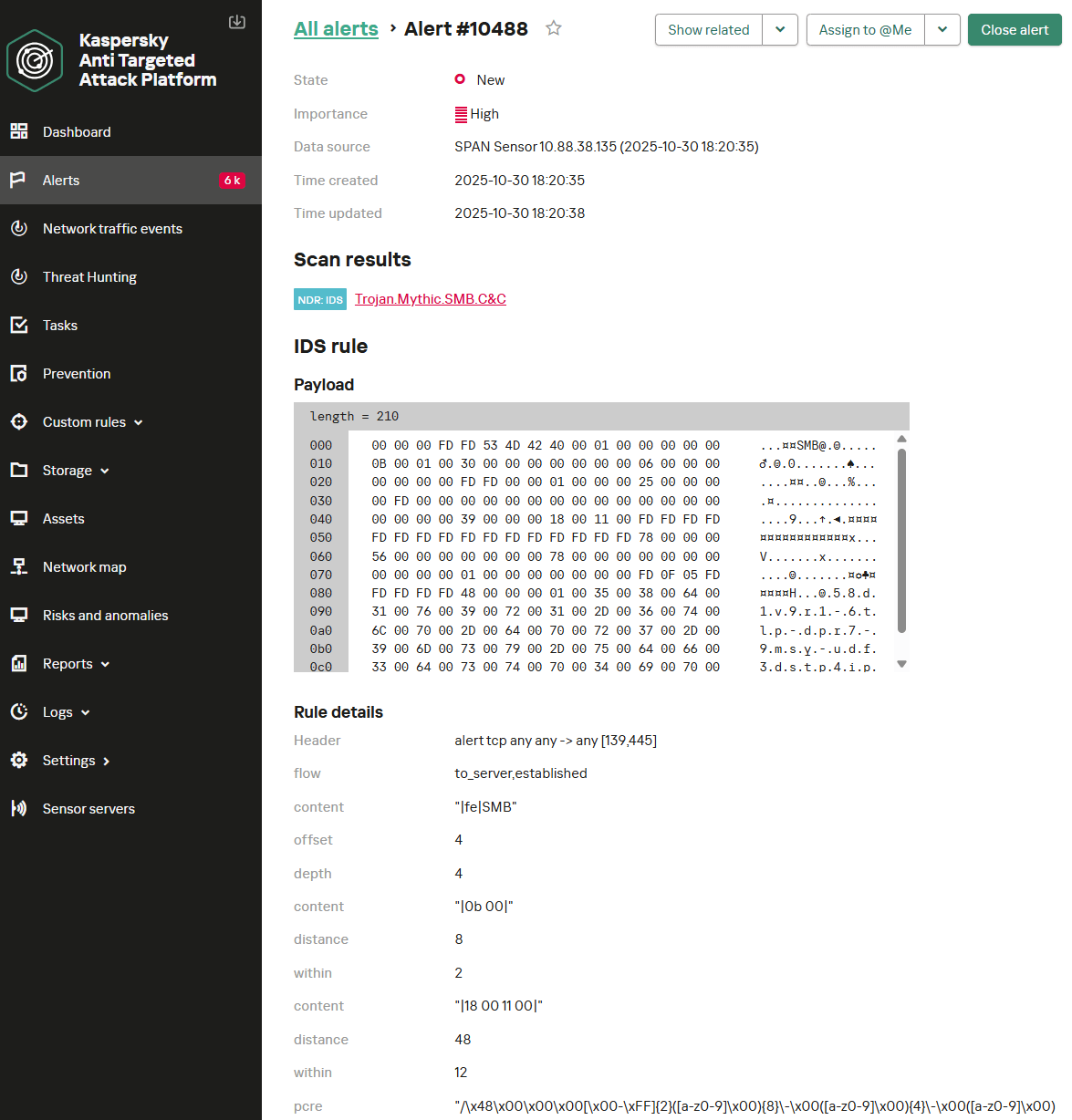

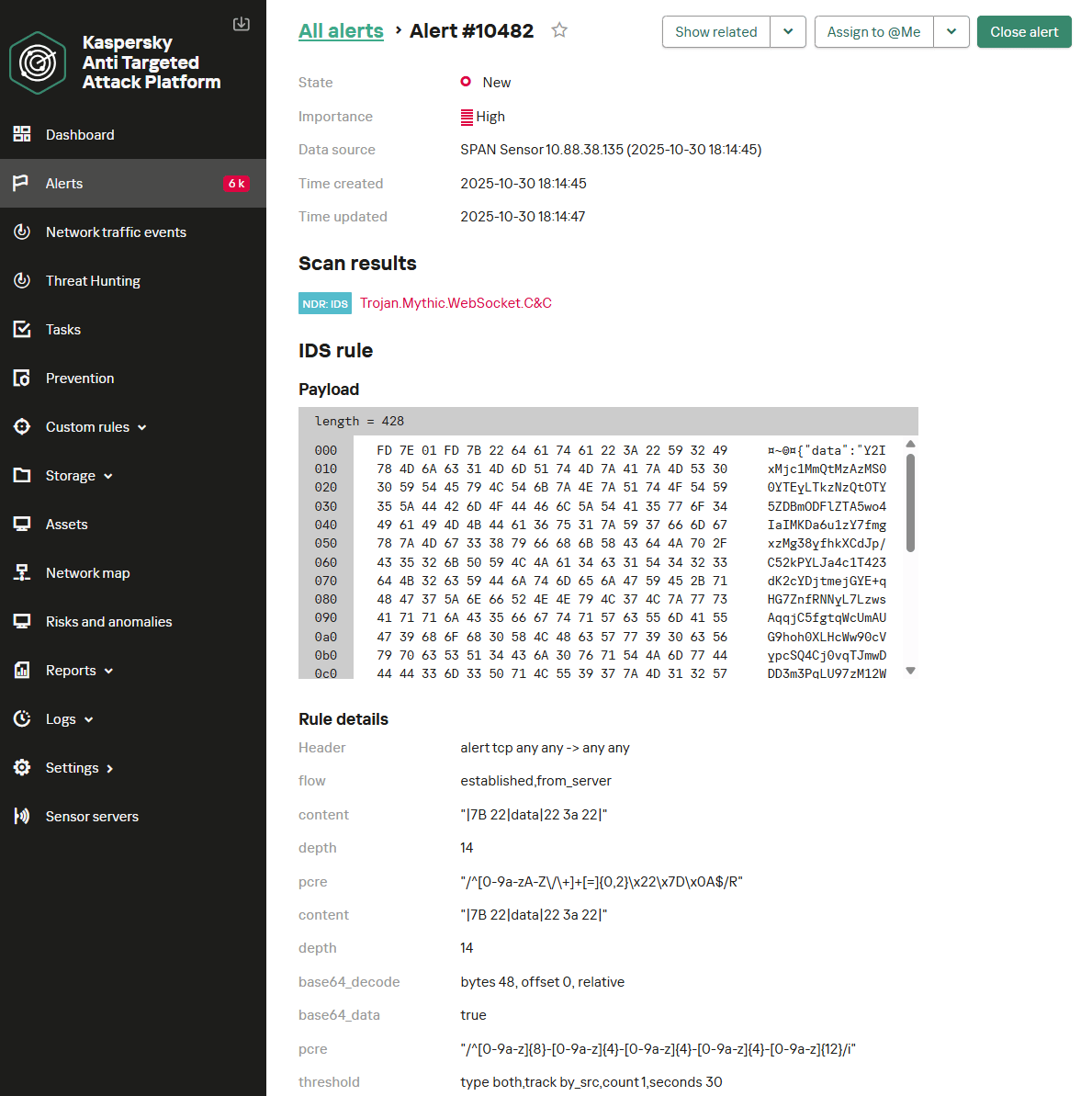

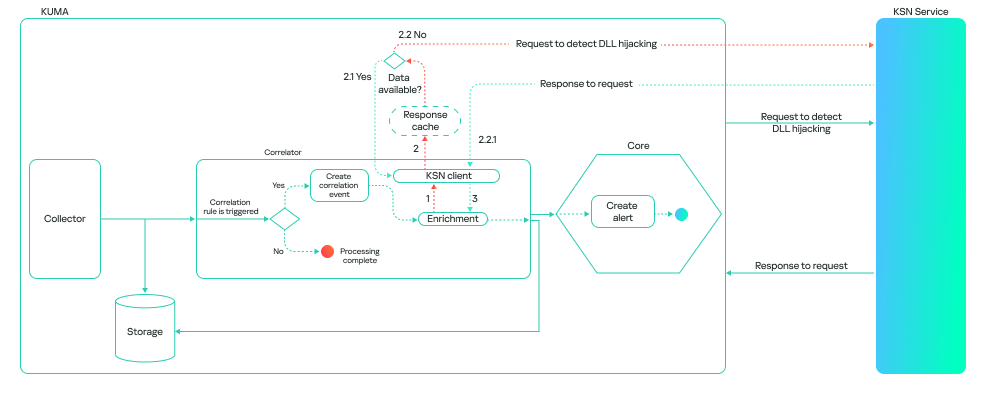

Lack of integration with indicators of compromise

SIEM integrations with other systems are generally a critical part of both event processing and alert enrichment. In at least one specific case, their presence directly impacts detection performance: integration with technical Threat Intelligence data or IoCs (indicators of compromise).

A SIEM allows conveniently checking objects against various reputation databases or blocklists. Furthermore, there are numerous sources of this data that are ready to integrate natively with a SIEM or require minimal effort to incorporate.

Problem: There is no integration with TI data.

How to detect: Generally, IoCs are integrated into a SIEM at the system configuration level during deployment or subsequent optimization. The use of TI within a SIEM can be implemented at various levels:

- At the data source level. Some sources, such as NGFWs, add this information to events involving relevant objects.

- At the SIEM native functionality level. For example, Kaspersky SIEM integrates with CyberTrace indicators, which add object reputation information at the moment of processing an event from a source.

- At the detection logic level. Information about IoCs is stored in various active lists, and correlation rules match objects against these to enrich the event.

Furthermore, TI data does not appear in a SIEM out of thin air. It is either provided by external suppliers (commercially or in an open format) or is part of the built-in functionality of the security tools in use. For instance, various NGFW systems can additionally check the reputation of external IP addresses or domains that users are accessing. Therefore, the first step is to determine whether you are receiving information about indicators of compromise and in what form (whether external providers’ feeds have been integrated and/or the deployed security tools have this capability). It is worth noting that receiving TI data only at the security tool level does not always cover all types of IoCs.

If data is being received in some form, the next step is to verify that the SIEM is utilizing it. For TI-related events coming from security tools, the SIEM needs a correlation rule developed to generate alerts. Thus, checking integration in this case involves determining the capabilities of the security tools, searching for the corresponding events in the SIEM, and identifying whether there is detection logic associated with these events. If events from the security tools are absent, the source audit configuration should be assessed to see if the telemetry type in question is being forwarded to the SIEM at all. If normalization is the issue, you should assess parsing accuracy and reconfigure the normalizer.

If TI data comes from external providers, determine how it is processed within the organization. Is there a centralized system for aggregating and managing threat data (such as CyberTrace), or is the information stored in, say, CSV files?

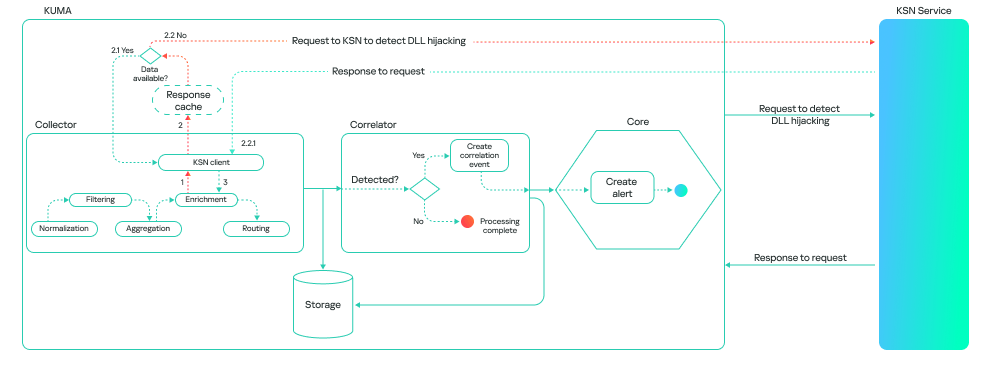

In the former case (there is a threat data aggregation and management system) you must check if it is integrated with the SIEM. For Kaspersky SIEM and CyberTrace, this integration is handled through the SIEM interface. Following this, SIEM event flows are directed to the threat data aggregation and management system, where matches are identified and alerts are generated, and then both are sent back to the SIEM. Therefore, checking the integration involves ensuring that all collectors receiving events that may contain IoCs are forwarding those events to the threat data aggregation and management system. We also recommend checking if the SIEM has a correlation rule that generates an alert based on matching detected objects with IoCs.

In the latter case (threat information is stored in files), you must confirm that the SIEM has a collector and normalizer configured to load this data into the system as events. Also, verify that logic is configured for storing this data within the SIEM for use in correlation. This is typically done with the help of lists that contain the obtained IoCs. Finally, check if a correlation rule exists that compares the event flow against these IoC lists.

As the examples illustrate, integration with TI in standard scenarios ultimately boils down to developing a final correlation rule that triggers an alert upon detecting a match with known IoCs. Given the variety of integration methods, creating and providing a universal out-of-the-box rule is difficult. Therefore, in most cases, to ensure IoCs are connected to the SIEM, you need to determine if the company has developed that rule (the existence of the rule) and if it has been correctly configured. If no correlation rule exists in the system, we recommend creating one based on the TI integration methods implemented in your infrastructure. If a rule does exist, its functionality must be verified: if there are no alerts from it, analyze its trigger conditions against the event data visible in the SIEM and adjust it accordingly.

The SIEM is not kept up to date

For a SIEM to run effectively, it must contain current data about the infrastructure it monitors and the threats it’s meant to detect. Both elements change over time: new systems and software, users, security policies, and processes are introduced into the infrastructure, while attackers develop new techniques and tools. It is safe to assume that a perfectly configured and deployed SIEM system will no longer be able to fully see the altered infrastructure or the new threats after five years of running without additional configuration. Therefore, practically all components – event collection, detection, additional integrations for contextual information, and exclusions – must be maintained and kept up to date.

Furthermore, it is important to acknowledge that it is impossible to cover 100% of all threats. Continuous research into attacks, development of detection methods, and configuration of corresponding rules are a necessity. The SOC itself also evolves. As it reaches certain maturity levels, new growth opportunities open up for the team, requiring the utilization of new capabilities.

Problem: The SIEM has not evolved since its initial deployment.

How to detect: Compare the original statement of work or other deployment documentation against the current state of the system. If there have been no changes, or only minimal ones, it is highly likely that your SIEM has areas for growth and optimization. Any infrastructure is dynamic and requires continuous adaptation.

Other issues with SIEM implementation and operation

In this article, we have outlined the primary problems we identify during SIEM effectiveness assessments, but this list is not exhaustive. We also frequently encounter:

- Mismatch between license capacity and actual SIEM load. The problem is almost always the absence of events from sources, rather than an incorrect initial assessment of the organization’s needs.

- Lack of user rights management within the system (for example, every user is assigned the administrator role).

- Poor organization of customizable SIEM resources (rules, normalizers, filters, and so on). Examples include chaotic naming conventions, non-optimal grouping, and obsolete or test content intermixed with active content. We have encountered confusing resource names like

[dev] test_Add user to admin group_final2. - Use of out-of-the-box resources without adaptation to the organization’s infrastructure. To maximize a SIEM’s value, it is essential at a minimum to populate exception lists and specify infrastructure parameters: lists of administrators and critical services and hosts.

- Disabled native integrations with external systems, such as LDAP, DNS, and GeoIP.

Generally, most issues with SIEM effectiveness stem from the natural degradation (accumulation of errors) of the processes implemented within the system. Therefore, in most cases, maintaining effectiveness involves structuring these processes, monitoring the quality of SIEM engagement at all stages (source onboarding, correlation rule development, normalization, and so on), and conducting regular reviews of all system components and resources.

Conclusion

A SIEM is a powerful tool for monitoring and detecting threats, capable of identifying attacks at various stages across nearly any point in an organization’s infrastructure. However, if improperly configured and operated, it can become ineffective or even useless while still consuming significant resources. Therefore, it is crucial to periodically audit the SIEM’s components, settings, detection rules, and data sources.

If a SOC is overloaded or otherwise unable to independently identify operational issues with its SIEM, we offer Kaspersky SIEM platform users a service to assess its operation. Following the assessment, we provide a list of recommendations to address the issues we identify. That being said, it is important to clarify that these are not strict, prescriptive instructions, but rather highlight areas that warrant attention and analysis to improve the product’s performance, enhance threat detection accuracy, and enable more efficient SIEM utilization.