Reading view

Digital Forensics: AnyDesk – Favorite Tool of APTs

Welcome back, aspiring digital forensics investigators!

AnyDesk first appeared around 2014 and very quickly became one of the most popular tools for legitimate remote support and system administration across the world. It is lightweight, fast, easy to deploy. Unfortunately, those same qualities also made it extremely attractive to cybercriminals and advanced persistent threat groups. Over the last several years, AnyDesk has become one of the preferred tools used by attackers to maintain persistent access to compromised systems.

Attackers abuse AnyDesk in a few different ways. Sometimes they install it directly and configure a password for unattended access. Other times, they rely on the fact that many organizations already have AnyDesk installed legitimately. All the attacker needs to do is gain access to the endpoint, change the AnyDesk password or configure a new access profile, and they now have quiet, persistent access. Because remote access tools are so commonly used by administrators, this kind of persistence often goes unnoticed for days, weeks, or even months. During that time the attacker can come and go as they please. Many organizations do not monitor this activity closely, even when they have mature security monitoring in place. We have seen companies with large infrastructures and centralized logging completely ignore AnyDesk connections. This has allowed attackers to maintain footholds across geographically distributed networks until they were ready to launch ransomware operations. When the encryption finally hits critical assets and the cryptography is strong, the damage is often permanent, unless you have the key.

We also see attackers modifying registry settings so that the accessibility button at the Windows login screen opens a command prompt with the highest privileges. This allows them to trigger privileged shells tied in with their AnyDesk session while minimizing local event log traces of normal login activity. We demonstrated similar registry hijacking concepts previously in “PowerShell for Hackers – Basics.” If you want a sense of how widespread this abuse is, look at recent cyberwarfare reporting involving Russia.

Kaspersky has documented numerous incidents where AnyDesk was routinely used by hacktivists and financially motivated groups during post-compromise operations. In the ICS-CERT reporting for Q4 2024, for example, the “Crypt Ghouls” threat actor relied on tools like Mimikatz, PingCastle, Resocks, AnyDesk, and PsExec. In Q3 2024, the “BlackJack” group made heavy use of AnyDesk, Radmin, PuTTY and tunneling with ngrok to maintain persistence across Russian government, telecom, and industrial environments. And that’s just a glimpse of it.

Although AnyDesk is not the only remote access tool available, it stands out because of its polished graphical interface and ease of use. Many system administrators genuinely like it. That means you will regularly encounter it during investigations, whether it was installed for legitimate reasons or abused by an attacker.

With that in mind, let’s look at how to perform digital forensics on a workstation that has been compromised through AnyDesk.

Investigating AnyDesk Activity During an Incident

Today we are going to focus on the types of log files that can help you determine whether there has been unauthorized access through AnyDesk. These logs can reveal the attacker’s AnyDesk ID, their chosen display name, the operating system they used, and in some cases even their IP address. Interestingly, inexperienced attackers sometimes do not realize that AnyDesk transmits the local username as the connection name, which means their personal environment name may suddenly appear on the victim system. The logs can also help you understand whether there may have been file transfers or data exfiltration.

For many incident response cases, this level of insight is already extremely valuable. On top of that, collecting these logs and ingesting them into your SIEM can help you generate alerts on suspicious activity patterns such as unexpected night-time access. Hackers prefer to work when users are asleep, so after-hours access from a remote tool should always trigger your curiosity.

Here are the log files and full paths that you will need for this analysis:

C:\Users\%username%\AppData\Roaming\AnyDesk\ad.trace

C:\Users\%username%\AppData\Roaming\AnyDesk\connection_trace.txt

C:\ProgramData\AnyDesk\ad_svc.trace

C:\ProgramData\AnyDesk\connection_trace.txtAnyDesk can be used in two distinct ways. The first is as a portable executable. In that case, the user runs the program directly without installing it. When used this way, the logs are stored under the user’s AppData directory. The second way is to install AnyDesk as a service. Once installed, it can be configured for unattended access, meaning the attacker can log in at any time using only a password, without the local user needing to confirm the session. When AnyDesk runs as a service, you should also examine the ProgramData directory as it will contain its own trace files. The AppData folder will still hold the ad.trace file, and together these files form the basis for your investigation.

With this background in place, let’s begin our analysis.

Connection Log Timestamps

The connection_trace.txt logs are relatively readable and give you a straightforward record of successful AnyDesk connections. Here is an example with a randomized AnyDesk ID:

Incoming 2025–07–25, 12:10 User 568936153 568936153

The real AnyDesk ID has been redacted. What matters is that the log clearly shows there was a successful inbound connection on 2025–07–25 at 12:10 UTC from the AnyDesk ID listed at the end. This already confirms that remote access occurred, but we can dig deeper using the other logs.

Gathering Information About the Intruder

Now we move into the part of the investigation where we begin to understand who our attacker might be. Although names, IDs, and even operating systems can be changed by the attacker at any time, patterns still emerge. Most attackers do not constantly change their display name unless they are extremely paranoid. Even then, the timestamps do not lie. Remote logins occurring repeatedly in the middle of the night are usually a strong indicator of unauthorized access.

We will work primarily with the ad.trace and ad_svc.trace files. These logs can be noisy, as they include a lot of error messages unrelated to the successful session. A practical way to cut through the noise is to search for specific keywords. In PowerShell, that might look like this:

PS > get-content .\ad.trace | select-string -list 'Remote OS', 'Incoming session', 'app.prepare_task', 'anynet.relay', 'anynet.any_socket', 'files', 'text offers' | tee adtrace.log

PS > get-content .\ad_svc.trace | select-string -list 'Remote OS', 'Incoming session', 'app.prepare_task', 'anynet.relay', 'anynet.any_socket', 'files', 'text offers' | tee adsvc.log

These commands filter out only the most interesting lines and save them into new files called adtrace.log and adsvc.log, while still letting you see the results in the console. The tee command behaves this way both in Windows and Linux. This small step makes the following analysis more efficient.

IP Address

In many cases, the ad_svc.trace log contains the external IP address from which the attacker connected. You will often see it recorded as “Logged in from,” alongside the AnyDesk ID listed as “Accepting from.” For the sake of privacy, these values were redacted in the screenshot we worked from, but they can be viewed easily inside the adsvc.log file you created earlier.

Once you have the IP address, you can enrich it further inside your SIEM. Geolocation, ASN information, and historical lookups may help you understand whether the attacker used a VPN, a hosting provider, a compromised endpoint, or even their home ISP.

Name & OS Information

Inside ad.trace you will generally find the attacker’s display name in lines referring to “Incoming session request.” Right next to that field you will see the corresponding AnyDesk ID. You may also see references to the attacker’s operating system.

In the example we examined, the attacker was connecting from a Linux machine and had set their display name to “IT Dep” in an attempt to appear legitimate. As you can imagine, users do not always question a remote session labeled as IT support, especially if the attacker acts confidently.

Data Exfiltration

AnyDesk does not only provide screen control. It also supports file transfer both ways. That means attackers can upload malware or exfiltrate sensitive company data directly through the session. In the ad.trace logs you will sometimes see references such as “Preparing files in …” which indicate file operations are occurring.

This line alone does not always tell you what exact files were transferred, especially if the attacker worked out of temporary directories. However, correlating those timestamps with standard Windows forensic artifacts, such as recent files, shellbags, jump lists, or server access logs, often reveals exactly what the attacker viewed or copied. If they accessed remote file servers during the session, those server logs combined with your AnyDesk timestamps can paint a very clear picture of what happened.

In our case, the attacker posing as the “IT Dep” accessed and exfiltrated files stored in the Documents folder of the manager who used that workstation.

Summary

Given how widespread AnyDesk is in both legitimate IT environments and malicious campaigns, you should always consider it a high-priority artifact in your digital forensics and incident response workflows. Make sure the relevant AnyDesk log files are consistently collected and ingested into your SIEM so that suspicious activity does not go unnoticed, especially outside business hours. Understanding how to interpret these logs shows the attacker’s behavior that otherwise feels invisible.

Our team strongly encourages you to remain aware of AnyDesk abuse patterns and to include them explicitly in your investigation playbooks. If you need any support building monitoring, tuning alerts, or analyzing remote access traces during an active case, we are always happy to help you strengthen your security posture.

Why your organization needs a Cisco Talos Incident Response Retainer

How we trained an ML model to detect DLL hijacking

DLL hijacking is a common technique in which attackers replace a library called by a legitimate process with a malicious one. It is used by both creators of mass-impact malware, like stealers and banking Trojans, and by APT and cybercrime groups behind targeted attacks. In recent years, the number of DLL hijacking attacks has grown significantly.

Trend in the number of DLL hijacking attacks. 2023 data is taken as 100% (download)

We have observed this technique and its variations, like DLL sideloading, in targeted attacks on organizations in Russia, Africa, South Korea, and other countries and regions. Lumma, one of 2025’s most active stealers, uses this method for distribution. Threat actors trying to profit from popular applications, such as DeepSeek, also resort to DLL hijacking.

Detecting a DLL substitution attack is not easy because the library executes within the trusted address space of a legitimate process. So, to a security solution, this activity may look like a trusted process. Directing excessive attention to trusted processes can compromise overall system performance, so you have to strike a delicate balance between a sufficient level of security and sufficient convenience.

Detecting DLL hijacking with a machine-learning model

Artificial intelligence can help where simple detection algorithms fall short. Kaspersky has been using machine learning for 20 years to identify malicious activity at various stages. The AI expertise center researches the capabilities of different models in threat detection, then trains and implements them. Our colleagues at the threat intelligence center approached us with a question of whether machine learning could be used to detect DLL hijacking, and more importantly, whether it would help improve detection accuracy.

Preparation

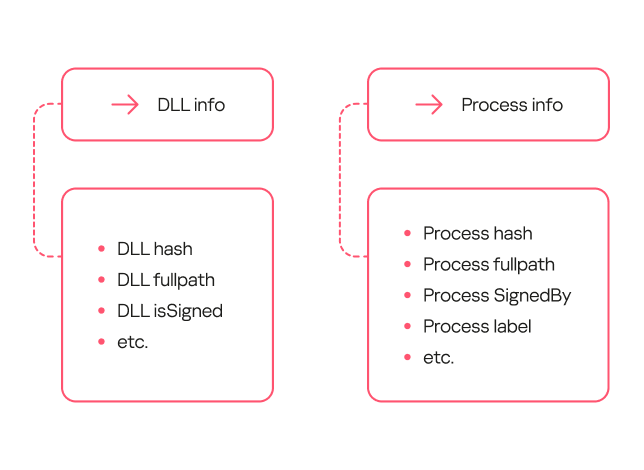

To determine if we could train a model to distinguish between malicious and legitimate library loads, we first needed to define a set of features highly indicative of DLL hijacking. We identified the following key features:

- Wrong library location. Many standard libraries reside in standard directories, while a malicious DLL is often found in an unusual location, such as the same folder as the executable that calls it.

- Wrong executable location. Attackers often save executables in non-standard paths, like temporary directories or user folders, instead of %Program Files%.

- Renamed executable. To avoid detection, attackers frequently save legitimate applications under arbitrary names.

- Library size has changed, and it is no longer signed.

- Modified library structure.

Training sample and labeling

For the training sample, we used dynamic library load data provided by our internal automatic processing systems, which handle millions of files every day, and anonymized telemetry, such as that voluntarily provided by Kaspersky users through Kaspersky Security Network.

The training sample was labeled in three iterations. Initially, we could not automatically pull event labeling from our analysts that indicated whether an event was a DLL hijacking attack. So, we used data from our databases containing only file reputation, and labeled the rest of the data manually. We labeled as DLL hijacking those library-call events where the process was definitively legitimate but the DLL was definitively malicious. However, this labeling was not enough because some processes, like “svchost”, are designed mainly to load various libraries. As a result, the model we trained on this data had a high rate of false positives and was not practical for real-world use.

In the next iteration, we additionally filtered malicious libraries by family, keeping only those which were known to exhibit DLL-hijacking behavior. The model trained on this refined data showed significantly better accuracy and essentially confirmed our hypothesis that we could use machine learning to detect this type of attacks.

At this stage, our training dataset had tens of millions of objects. This included about 20 million clean files and around 50,000 definitively malicious ones.

| Status | Total | Unique files |

| Unknown | ~ 18M | ~ 6M |

| Malicious | ~ 50K | ~ 1,000 |

| Clean | ~ 20M | ~ 250K |

We then trained subsequent models on the results of their predecessors, which had been verified and further labeled by analysts. This process significantly increased the efficiency of our training.

Loading DLLs: what does normal look like?

So, we had a labeled sample with a large number of library loading events from various processes. How can we describe a “clean” library? Using a process name + library name combination does not account for renamed processes. Besides, a legitimate user, not just an attacker, can rename a process. If we used the process hash instead of the name, we would solve the renaming problem, but then every version of the same library would be treated as a separate library. We ultimately settled on using a library name + process signature combination. While this approach considers all identically named libraries from a single vendor as one, it generally produces a more or less realistic picture.

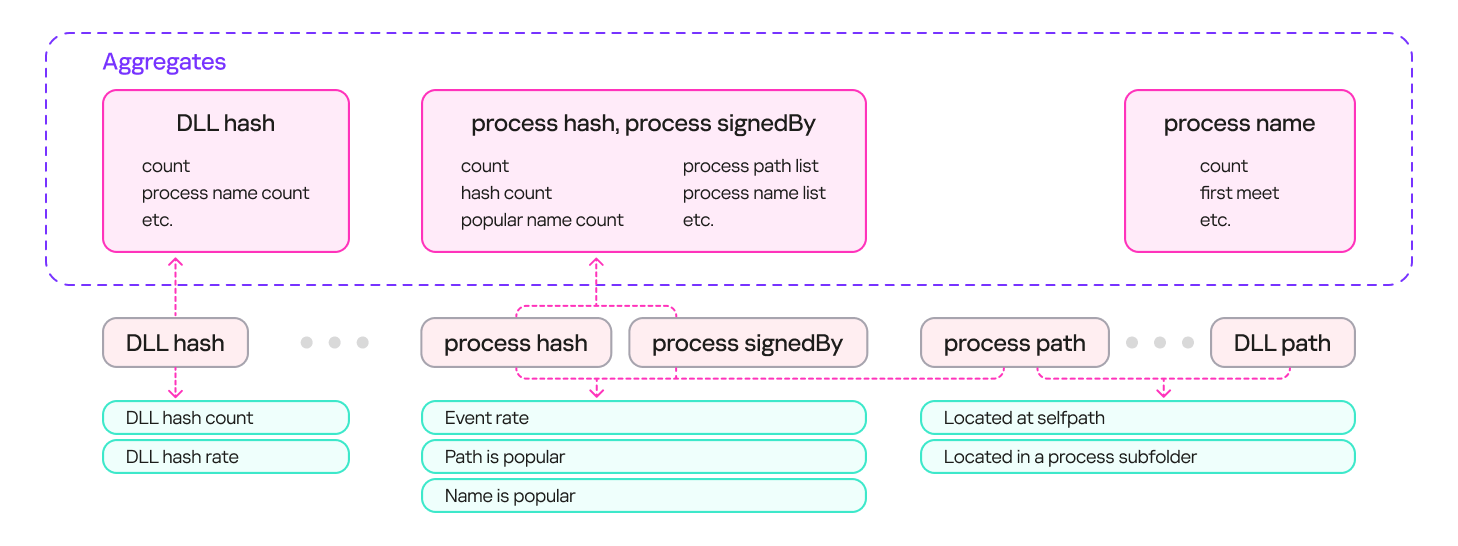

To describe safe library loading events, we used a set of counters that included information about the processes (the frequency of a specific process name for a file with a given hash, the frequency of a specific file path for a file with that hash, and so on), information about the libraries (the frequency of a specific path for that library, the percentage of legitimate launches, and so on), and event properties (that is, whether the library is in the same directory as the file that calls it).

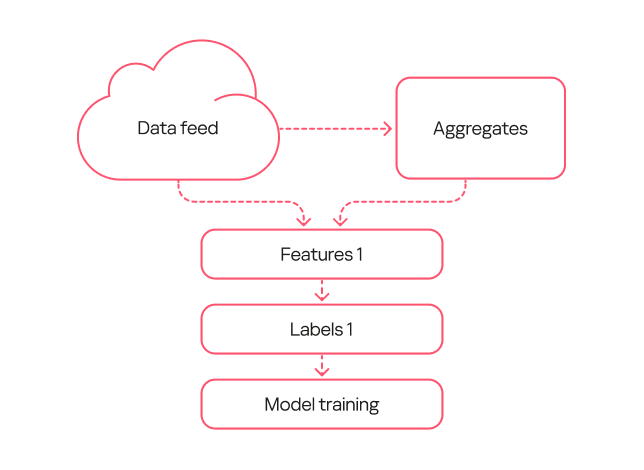

The result was a system with multiple aggregates (sets of counters and keys) that could describe an input event. These aggregates can contain a single key (e.g., a DLL’s hash sum) or multiple keys (e.g., a process’s hash sum + process signature). Based on these aggregates, we can derive a set of features that describe the library loading event. The diagram below provides examples of how these features are derived:

Loading DLLs: how to describe hijacking

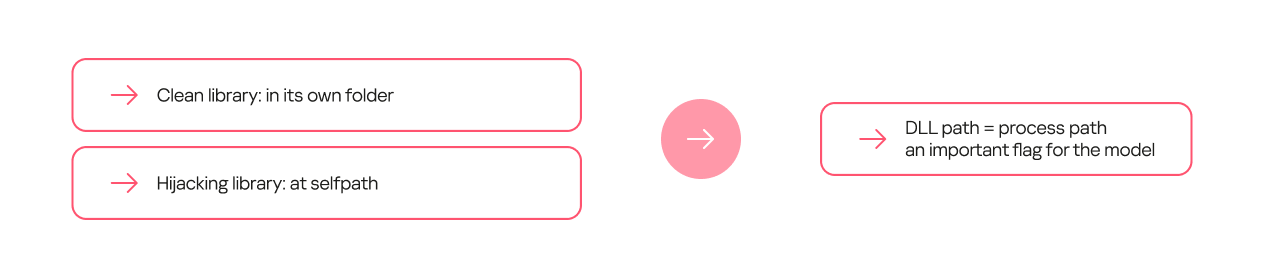

Certain feature combinations (dependencies) strongly indicate DLL hijacking. These can be simple dependencies. For some processes, the clean library they call always resides in a separate folder, while the malicious one is most often placed in the process folder.

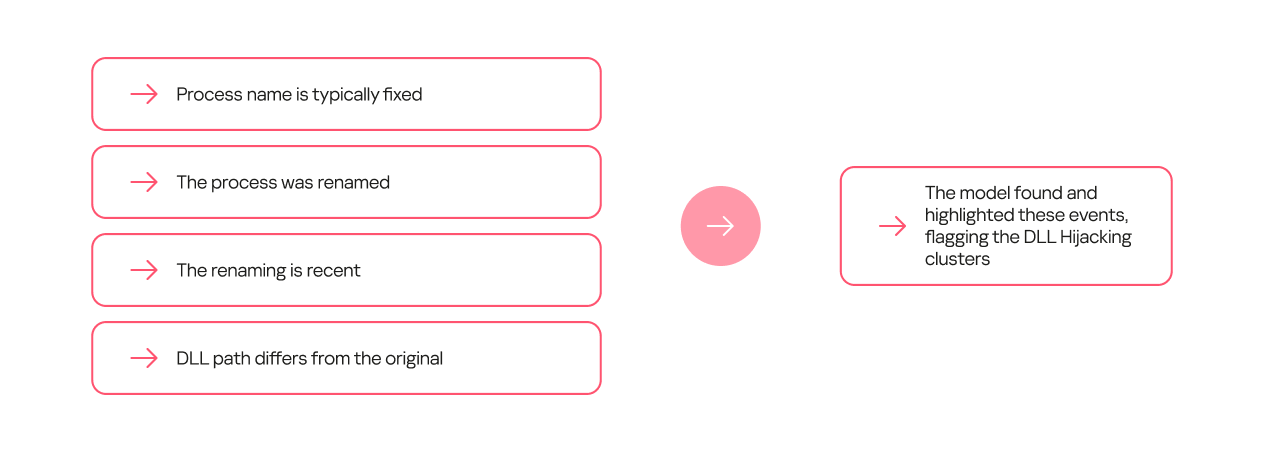

Other dependencies can be more complex and require several conditions to be met. For example, a process renaming itself does not, on its own, indicate DLL hijacking. However, if the new name appears in the data stream for the first time, and the library is located on a non-standard path, it is highly likely to be malicious.

Model evolution

Within this project, we trained several generations of models. The primary goal of the first generation was to show that machine learning could at all be applied to detecting DLL hijacking. When training this model, we used the broadest possible interpretation of the term.

The model’s workflow was as simple as possible:

- We took a data stream and extracted a frequency description for selected sets of keys.

- We took the same data stream from a different time period and obtained a set of features.

- We used type 1 labeling, where events in which a legitimate process loaded a malicious library from a specified set of families were marked as DLL hijacking.

- We trained the model on the resulting data.

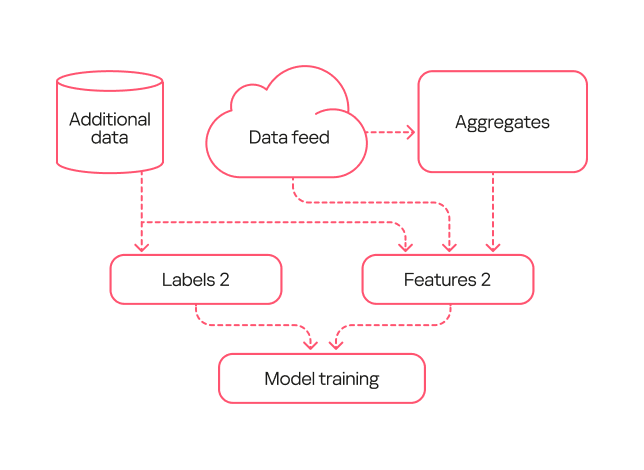

The second-generation model was trained on data that had been processed by the first-generation model and verified by analysts (labeling type 2). Consequently, the labeling was more precise than during the training of the first model. Additionally, we added more features to describe the library structure and slightly complicated the workflow for describing library loads.

Based on the results from this second-generation model, we were able to identify several common types of false positives. For example, the training sample included potentially unwanted applications. These can, in certain contexts, exhibit behavior similar to DLL hijacking, but they are not malicious and rarely belong to this attack type.

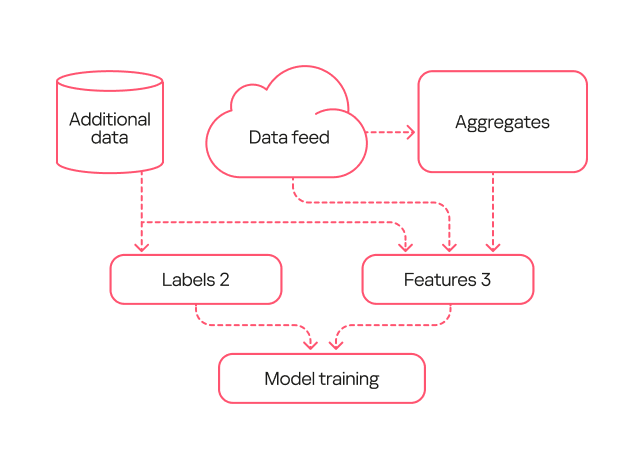

We fixed these errors in the third-generation model. First, with the help of analysts, we flagged the potentially unwanted applications in the training sample so the model would not detect them. Second, in this new version, we used an expanded labeling that included useful detections from both the first and second generations. Additionally, we expanded the feature description through one-hot encoding — a technique for converting categorical features into a binary format — for certain fields. Also, since the volume of events processed by the model increased over time, this version added normalization of all features based on the data flow size.

Comparison of the models

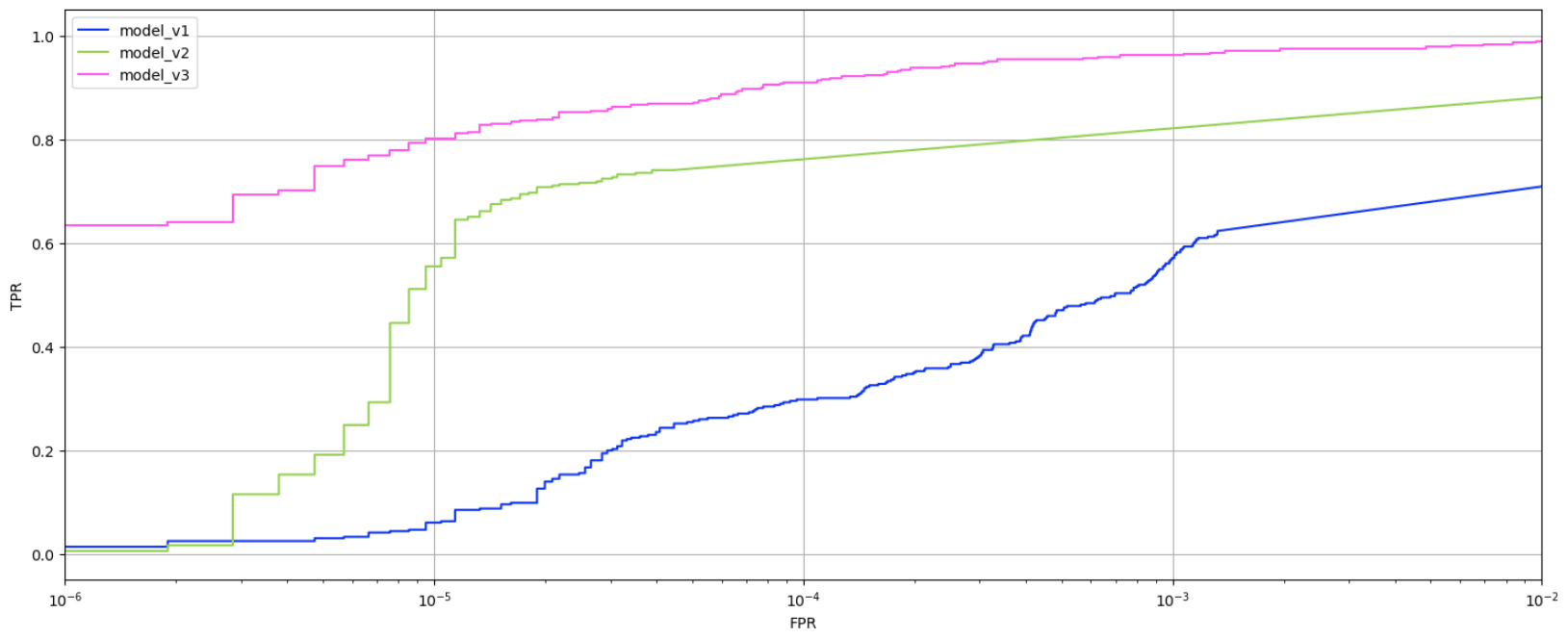

To evaluate the evolution of our models, we applied them to a test data set none of them had worked with before. The graph below shows the ratio of true positive to false positive verdicts for each model.

As the models evolved, the percentage of true positives grew. While the first-generation model achieved a relatively good result (0.6 or higher) only with a very high false positive rate (10⁻³ or more), the second-generation model reached this at 10⁻⁵. The third-generation model, at the same low false positive rate, produced 0.8 true positives, which is considered a good result.

Evaluating the models on the data stream at a fixed score shows that the absolute number of new events labeled as DLL Hijacking increased from one generation to the next. That said, evaluating the models by their false verdict rate also helps track progress: the first model has a fairly high error rate, while the second and third generations have significantly lower ones.

False positives rate among model outputs, July 2024 – August 2025 (download)

Practical application of the models

All three model generations are used in our internal systems to detect likely cases of DLL hijacking within telemetry data streams. We receive 6.5 million security events daily, linked to 800,000 unique files. Aggregates are built from this sample at a specified interval, enriched, and then fed into the models. The output data is then ranked by model and by the probability of DLL hijacking assigned to the event, and then sent to our analysts. For instance, if the third-generation model flags an event as DLL hijacking with high confidence, it should be investigated first, whereas a less definitive verdict from the first-generation model can be checked last.

Simultaneously, the models are tested on a separate data stream they have not seen before. This is done to assess their effectiveness over time, as a model’s detection performance can degrade. The graph below shows that the percentage of correct detections varies slightly over time, but on average, the models detect 70–80% of DLL hijacking cases.

DLL hijacking detection trends for all three models, October 2024 – September 2025 (download)

Additionally, we recently deployed a DLL hijacking detection model into the Kaspersky SIEM, but first we tested the model in the Kaspersky MDR service. During the pilot phase, the model helped to detect and prevent a number of DLL hijacking incidents in our clients’ systems. We have written a separate article about how the machine learning model for detecting targeted attacks involving DLL hijacking works in Kaspersky SIEM and the incidents it has identified.

Conclusion

Based on the training and application of the three generations of models, the experiment to detect DLL hijacking using machine learning was a success. We were able to develop a model that distinguishes events resembling DLL hijacking from other events, and refined it to a state suitable for practical use, not only in our internal systems but also in commercial products. Currently, the models operate in the cloud, scanning hundreds of thousands of unique files per month and detecting thousands of files used in DLL hijacking attacks each month. They regularly identify previously unknown variations of these attacks. The results from the models are sent to analysts who verify them and create new detection rules based on their findings.

Detecting DLL hijacking with machine learning: real-world cases

Introduction

Our colleagues from the AI expertise center recently developed a machine-learning model that detects DLL-hijacking attacks. We then integrated this model into the Kaspersky Unified Monitoring and Analysis Platform SIEM system. In a separate article, our colleagues shared how the model had been created and what success they had achieved in lab environments. Here, we focus on how it operates within Kaspersky SIEM, the preparation steps taken before its release, and some real-world incidents it has already helped us uncover.

How the model works in Kaspersky SIEM

The model’s operation generally boils down to a step-by-step check of all DLL libraries loaded by processes in the system, followed by validation in the Kaspersky Security Network (KSN) cloud. This approach allows local attributes (path, process name, and file hashes) to be combined with a global knowledge base and behavioral indicators, which significantly improves detection quality and reduces the probability of false positives.

The model can run in one of two modes: on a correlator or on a collector. A correlator is a SIEM component that performs event analysis and correlation based on predefined rules or algorithms. If detection is configured on a correlator, the model checks events that have already triggered a rule. This reduces the volume of KSN queries and the model’s response time.

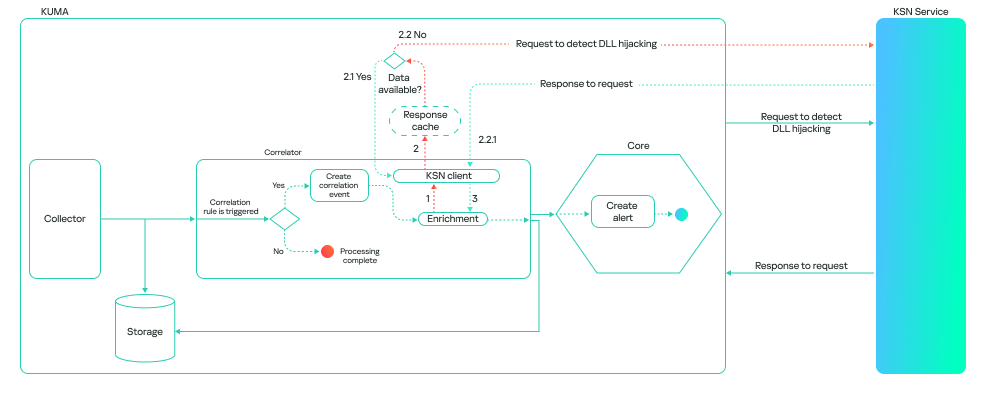

This is how it looks:

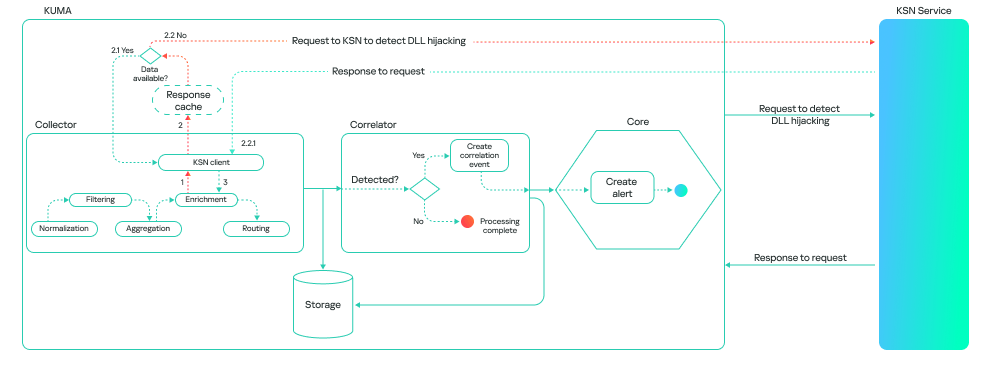

A collector is a software or hardware component of a SIEM platform that collects and normalizes events from various sources, and then delivers these events to the platform’s core. If detection is configured on a collector, the model processes all events associated with various processes loading libraries, provided these events meet the following conditions:

- The path to the process file is known.

- The path to the library is known.

- The hashes of the file and the library are available.

This method consumes more resources, and the model’s response takes longer than it does on a correlator. However, it can be useful for retrospective threat hunting because it allows you to check all events logged by Kaspersky SIEM. The model’s workflow on a collector looks like this:

It is important to note that the model is not limited to a binary “malicious/non-malicious” assessment; it ranks its responses by confidence level. This allows it to be used as a flexible tool in SOC practice. Examples of possible verdicts:

- 0: data is being processed.

- 1: maliciousness not confirmed. This means the model currently does not consider the library malicious.

- 2: suspicious library.

- 3: maliciousness confirmed.

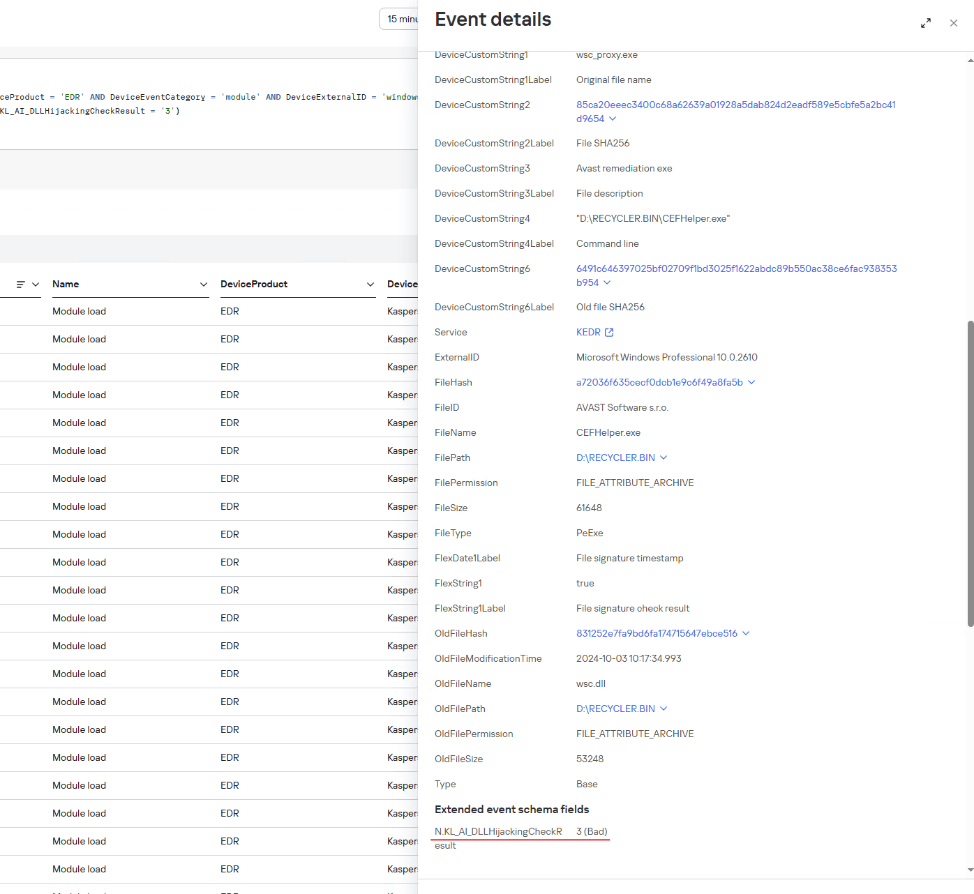

A Kaspersky SIEM rule for detecting DLL hijacking would look like this:

N.KL_AI_DLLHijackingCheckResult > 1

Embedding the model into the Kaspersky SIEM correlator automates the process of finding DLL-hijacking attacks, making it possible to detect them at scale without having to manually analyze hundreds or thousands of loaded libraries. Furthermore, when combined with correlation rules and telemetry sources, the model can be used not just as a standalone module but as part of a comprehensive defense against infrastructure attacks.

Incidents detected during the pilot testing of the model in the MDR service

Before being released, the model (as part of the Kaspersky SIEM platform) was tested in the MDR service, where it was trained to identify attacks on large datasets supplied by our telemetry. This step was necessary to ensure that detection works not only in lab settings but also in real client infrastructures.

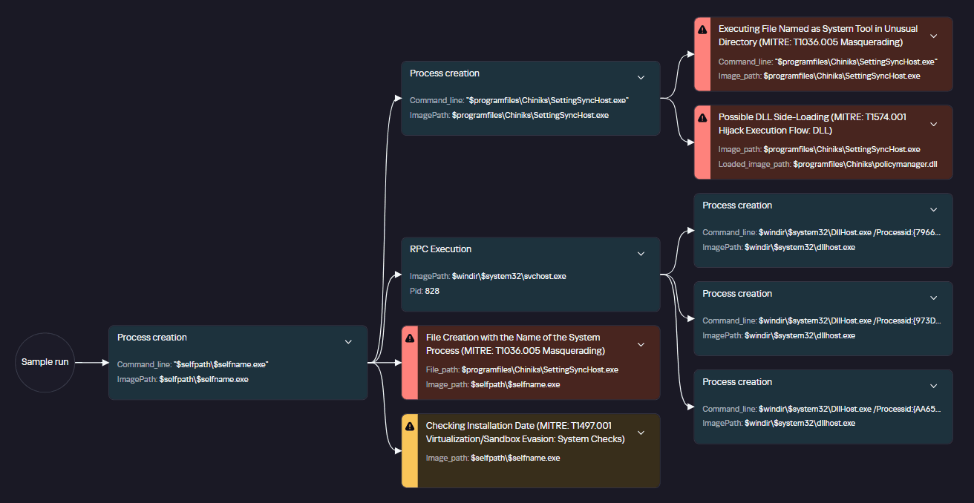

During the pilot testing, we verified the model’s resilience to false positives and its ability to correctly classify behavior even in non-typical DLL-loading scenarios. As a result, several real-world incidents were successfully detected where attackers used one type of DLL hijacking — the DLL Sideloading technique — to gain persistence and execute their code in the system.

Let us take a closer look at the three most interesting of these.

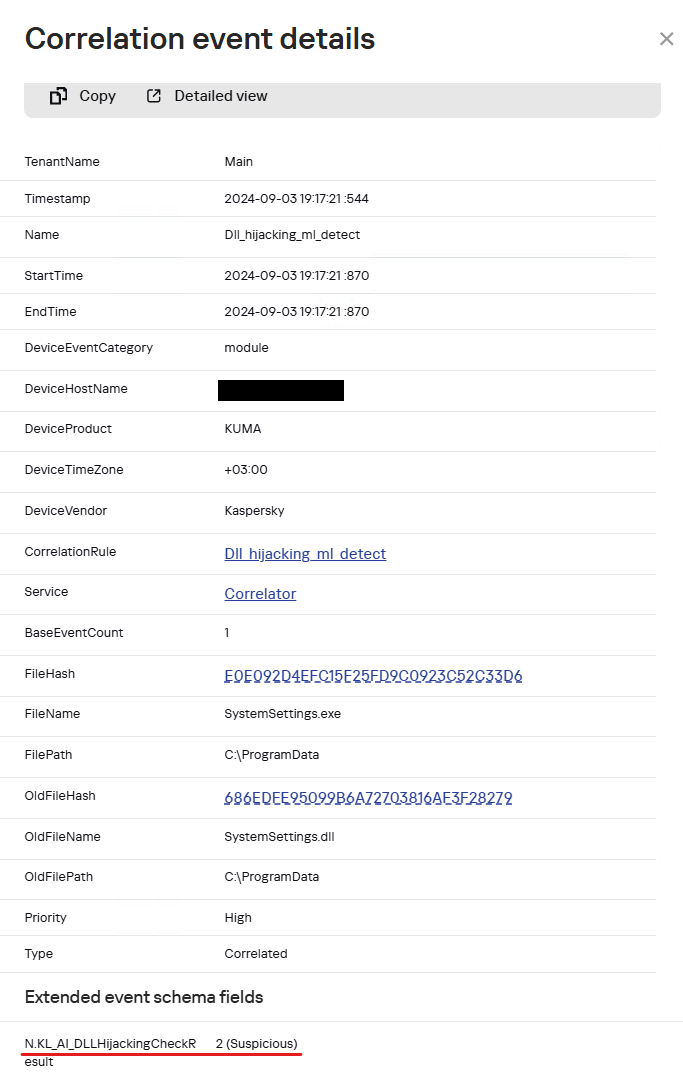

Incident 1. ToddyCat trying to launch Cobalt Strike disguised as a system library

In one incident, the attackers successfully leveraged the vulnerability CVE-2021-27076 to exploit a SharePoint service that used IIS as a web server. They ran the following command:

c:\windows\system32\inetsrv\w3wp.exe -ap "SharePoint - 80" -v "v4.0" -l "webengine4.dll" -a \\.\pipe\iisipmd32ded38-e45b-423f-804d-34471928538b -h "C:\inetpub\temp\apppools\SharePoint - 80\SharePoint - 80.config" -w "" -m 0

After the exploitation, the IIS process created files that were later used to run malicious code via the DLL sideloading technique (T1574.001 Hijack Execution Flow: DLL):

C:\ProgramData\SystemSettings.exe C:\ProgramData\SystemSettings.dll

SystemSettings.dll is the name of a library associated with the Windows Settings application (SystemSettings.exe). The original library contains code and data that the Settings application uses to manage and configure various system parameters. However, the library created by the attackers has malicious functionality and is only pretending to be a system library.

Later, to establish persistence in the system and launch a DLL sideloading attack, a scheduled task was created, disguised as a Microsoft Edge browser update. It launches a SystemSettings.exe file, which is located in the same directory as the malicious library:

Schtasks /create /ru "SYSTEM" /tn "\Microsoft\Windows\Edge\Edgeupdates" /sc DAILY /tr "C:\ProgramData\SystemSettings.exe" /F

The task is set to run daily.

When the SystemSettings.exe process is launched, it loads the malicious DLL. As this happened, the process and library data were sent to our model for analysis and detection of a potential attack.

The resulting data helped our analysts highlight a suspicious DLL and analyze it in detail. The library was found to be a Cobalt Strike implant. After loading it, the SystemSettings.exe process attempted to connect to the attackers’ command-and-control server.

DNS query: connect-microsoft[.]com DNS query type: AAAA DNS response: ::ffff:8.219.1[.]155; 8.219.1[.]155:8443

After establishing a connection, the attackers began host reconnaissance to gather various data to develop their attack.

C:\ProgramData\SystemSettings.exe whoami /priv hostname reg query HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Cryptography /v MachineGuid powershell -c $psversiontable dotnet --version systeminfo reg query "HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\VMware, Inc.\VMware Drivers" cmdkey /list REG query "HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\Terminal Server\WinStations\RDP-Tcp" /v PortNumber reg query "HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Terminal Server Client\Servers netsh wlan show profiles netsh wlan show interfaces set net localgroup administrators net user net user administrator ipconfig /all net config workstation net view arp -a route print netstat -ano tasklist schtasks /query /fo LIST /v net start net share net use netsh firewall show config netsh firewall show state net view /domain net time /domain net group "domain admins" /domain net localgroup administrators /domain net group "domain controllers" /domain net accounts /domain nltest / domain_trusts reg query HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run reg query HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\RunOnce reg query HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Policies\Explorer\Run reg query HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\Software\Wow6432Node\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run reg query HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Wow6432Node\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\RunOnce

Based on the attackers’ TTPs, such as loading Cobalt Strike as a DLL, using the DLL sideloading technique (1, 2), and exploiting SharePoint, we can say with a high degree of confidence that the ToddyCat APT group was behind the attack. Thanks to the prompt response of our model, we were able to respond in time and block this activity, preventing the attackers from causing damage to the organization.

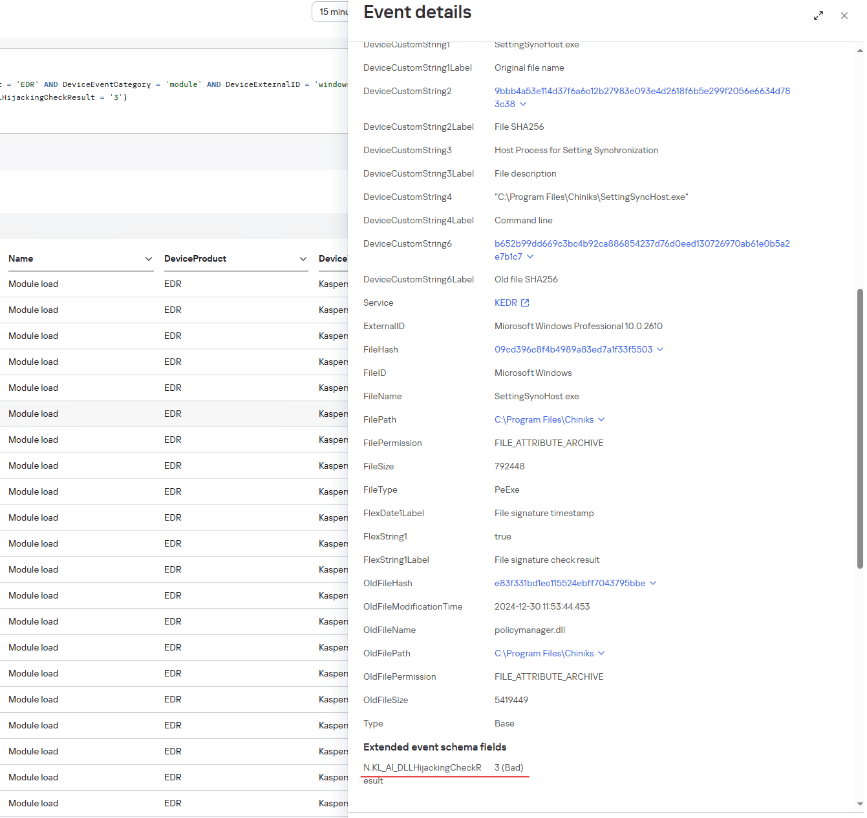

Incident 2. Infostealer masquerading as a policy manager

Another example was discovered by the model after a client was connected to MDR monitoring: a legitimate system file located in an application folder attempted to load a suspicious library that was stored next to it.

C:\Program Files\Chiniks\SettingSyncHost.exe C:\Program Files\Chiniks\policymanager.dll E83F331BD1EC115524EBFF7043795BBE

The SettingSyncHost.exe file is a system host process for synchronizing settings between one user’s different devices. Its 32-bit and 64-bit versions are usually located in C:\Windows\System32\ and C:\Windows\SysWOW64\, respectively. In this incident, the file location differed from the normal one.

Analysis of the library file loaded by this process showed that it was malware designed to steal information from browsers.

The file directly accesses browser files that contain user data.

C:\Users\<user>\AppData\Local\Google\Chrome\User Data\Local State

The library file is on the list of files used for DLL hijacking, as published in the HijackLibs project. The project contains a list of common processes and libraries employed in DLL-hijacking attacks, which can be used to detect these attacks.

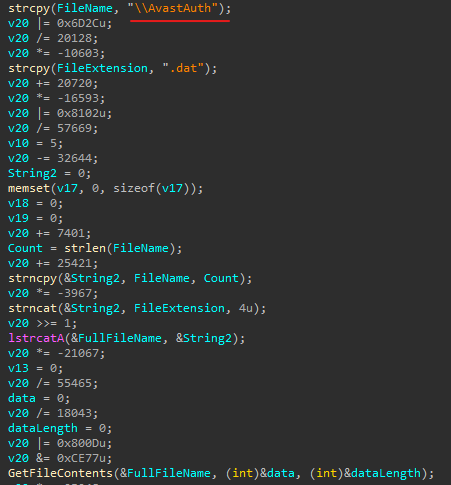

Incident 3. Malicious loader posing as a security solution

Another incident discovered by our model occurred when a user connected a removable USB drive:

Example of a Kaspersky SIEM event where a wsc.dll library was loaded from a USB drive, with a DLL Hijacking module verdict

The connected drive’s directory contained hidden folders with an identically named shortcut for each of them. The shortcuts had icons typically used for folders. Since file extensions were not shown by default on the drive, the user might have mistaken the shortcut for a folder and launched it. In turn, the shortcut opened the corresponding hidden folder and ran an executable file using the following command:

"%comspec%" /q /c "RECYCLER.BIN\1\CEFHelper.exe [$DIGITS] [$DIGITS]"

CEFHelper.exe is a legitimate Avast Antivirus executable that, through DLL sideloading, loaded the wsc.dll library, which is a malicious loader.

The loader opens a file named AvastAuth.dat, which contains an encrypted backdoor. The library reads the data from the file into memory, decrypts it, and executes it. After this, the backdoor attempts to connect to a remote command-and-control server.

The library file, which contains the malicious loader, is on the list of known libraries used for DLL sideloading, as presented on the HijackLibs project website.

Conclusion

Integrating the model into the product provided the means of early and accurate detection of DLL-hijacking attempts which previously might have gone unnoticed. Even during the pilot testing, the model proved its effectiveness by identifying several incidents using this technique. Going forward, its accuracy will only increase as data accumulates and algorithms are updated in KSN, making this mechanism a reliable element of proactive protection for corporate systems.

IoC

Legitimate files used for DLL hijacking

E0E092D4EFC15F25FD9C0923C52C33D6 loads SystemSettings.dll

09CD396C8F4B4989A83ED7A1F33F5503 loads policymanager.dll

A72036F635CECF0DCB1E9C6F49A8FA5B loads wsc.dll

Malicious files

EA2882B05F8C11A285426F90859F23C6 SystemSettings.dll

E83F331BD1EC115524EBFF7043795BBE policymanager.dll

831252E7FA9BD6FA174715647EBCE516 wsc.dll

Paths

C:\ProgramData\SystemSettings.exe

C:\ProgramData\SystemSettings.dll

C:\Program Files\Chiniks\SettingSyncHost.exe

C:\Program Files\Chiniks\policymanager.dll

D:\RECYCLER.BIN\1\CEFHelper.exe

D:\RECYCLER.BIN\1\wsc.dll

Forensic journey: hunting evil within AmCache

Introduction

When it comes to digital forensics, AmCache plays a vital role in identifying malicious activities in Windows systems. This artifact allows the identification of the execution of both benign and malicious software on a machine. It is managed by the operating system, and at the time of writing this article, there is no known way to modify or remove AmCache data. Thus, in an incident response scenario, it could be the key to identifying lost artifacts (e.g., ransomware that auto-deletes itself), allowing analysts to search for patterns left by the attacker, such as file names and paths. Furthermore, AmCache stores the SHA-1 hashes of executed files, which allows DFIR professionals to search public threat intelligence feeds — such as OpenTIP and VirusTotal — and generate rules for blocking this same file on other systems across the network.

This article presents a comprehensive analysis of the AmCache artifact, allowing readers to better understand its inner workings. In addition, we present a new tool named “AmCache-EvilHunter“, which can be used by any professional to easily parse the Amcache.hve file and extract IOCs. The tool is also able to query the aforementioned intelligence feeds to check for malicious file detections, this level of built-in automation reduces manual effort and speeds up threat detection, which is of significant value for analysts and responders.

The importance of evidence of execution

Evidence of execution is fundamentally important in digital forensics and incident response, since it helps investigators reconstruct how the system was used during an intrusion. Artifacts such as Prefetch, ShimCache, and UserAssist offer clues about what was executed. AmCache is also a robust artifact for evidencing execution, preserving metadata that indicates a file’s presence and execution, even if the file has been deleted or modified. An advantage of AmCache over other Windows artifacts is that unlike them, it stores the file hash, which is immensely useful for analysts, as it can be used to hunt malicious files across the network, increasing the likelihood of fully identifying, containing, and eradicating the threat.

Introduction to AmCache

Application Activity Cache (AmCache) was first introduced in Windows 7 and fully leveraged in Windows 8 and beyond. Its purpose is to replace the older RecentFileCache.bcf in newer systems. Unlike its predecessor, AmCache includes valuable forensic information about program execution, executed binaries and loaded drivers.

This artifact is stored as a registry hive file named Amcache.hve in the directory C:\Windows\AppCompat\Programs. The metadata stored in this file includes file paths, publisher data, compilation timestamps, file sizes, and SHA-1 hashes.

It is important to highlight that the AmCache format does not depend on the operating system version, but rather on the version of the libraries (DLLs) responsible for filling the cache. In this way, even Windows systems with different patch levels could have small differences in the structure of the AmCache files. The known libraries used for filling this cache are stored under %WinDir%\System32 with the following names:

- aecache.dll

- aeevts.dll

- aeinv.dll

- aelupsvc.dll

- aepdu.dll

- aepic.dll

It is worth noting that this artifact has its peculiarities and limitations. The AmCache computes the SHA-1 hash over only the first 31,457,280 bytes (≈31 MB) of each executable, so comparing its stored hash online can fail for files exceeding this size. Furthermore, Amcache.hve is not a true execution log: it records files in directories scanned by the Microsoft Compatibility Appraiser, executables and drivers copied during program execution, and GUI applications that required compatibility shimming. Only the last category reliably indicates actual execution. Items in the first two groups simply confirm file presence on the system, with no data on whether or when they ran.

In the same directory, we can find additional LOG files used to ensure Amcache.hve consistency and recovery operations:

- C:\Windows\AppCompat\Programs\Amcache.hve.*LOG1

- C:\Windows\AppCompat\Programs\Amcache.hve.*LOG2

The Amcache.hve file can be collected from a system for forensic analysis using tools like Aralez, Velociraptor, or Kape.

Amcache.hve structure

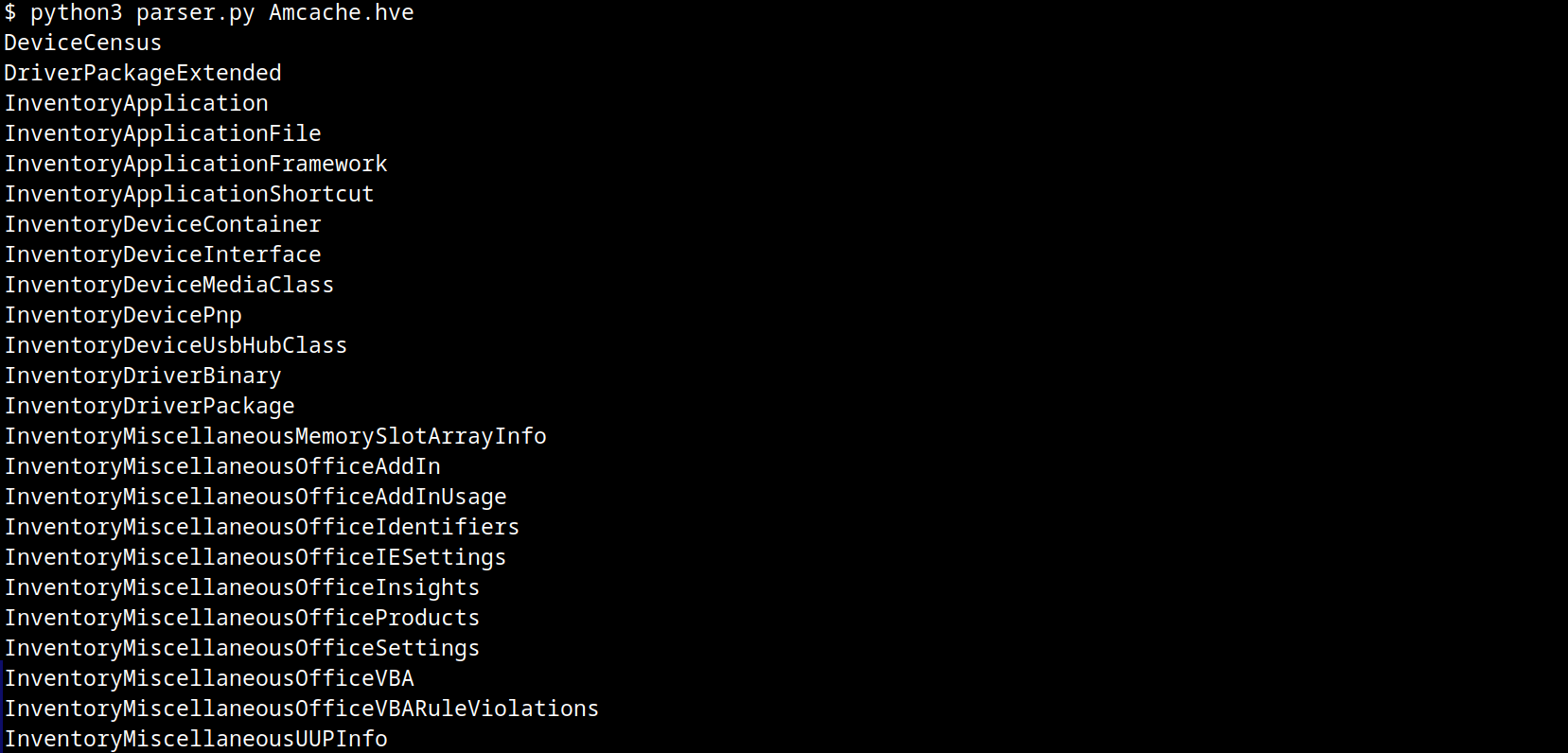

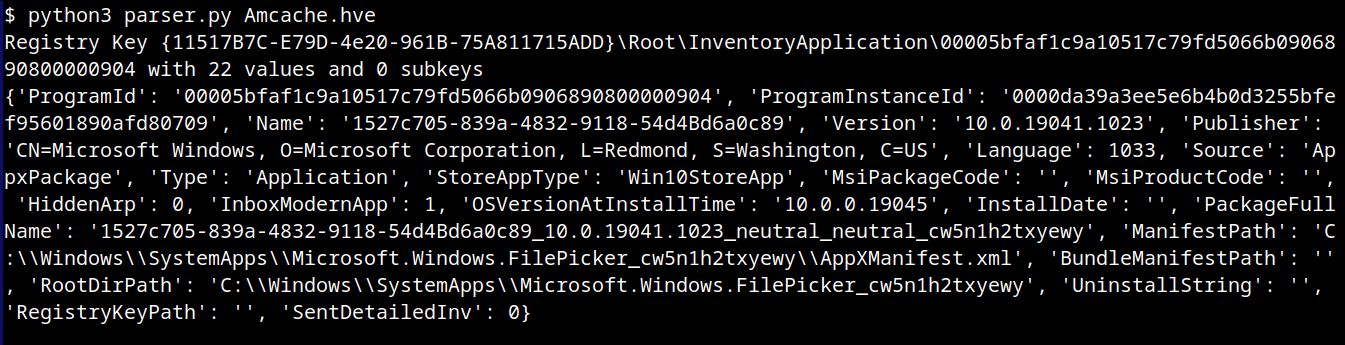

The Amcache.hve file is a Windows Registry hive in REGF format; it contains multiple subkeys that store distinct classes of data. A simple Python parser can be implemented to iterate through Amcache.hve and present its keys:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import sys

from Registry.Registry import Registry

hive = Registry(str(sys.argv[1]))

root = hive.open("Root")

for rec in root.subkeys():

print(rec.name())The result of this parser when executed is:

From a DFIR perspective, the keys that are of the most interest to us are InventoryApplicationFile, InventoryApplication, InventoryDriverBinary, and InventoryApplicationShortcut, which are described in detail in the following subsections.

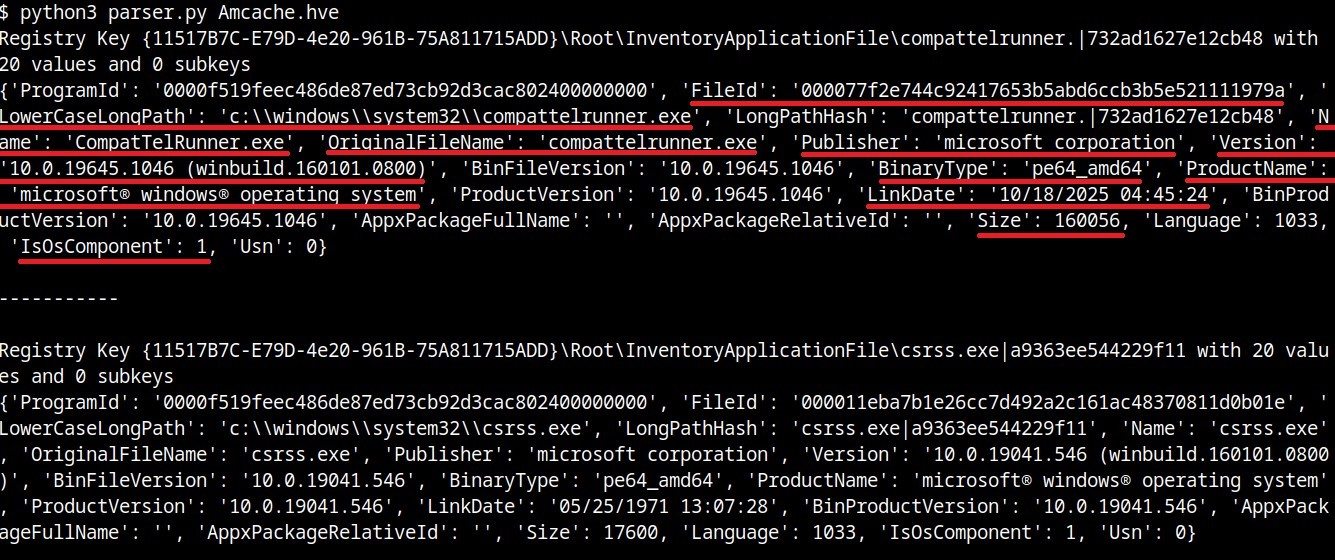

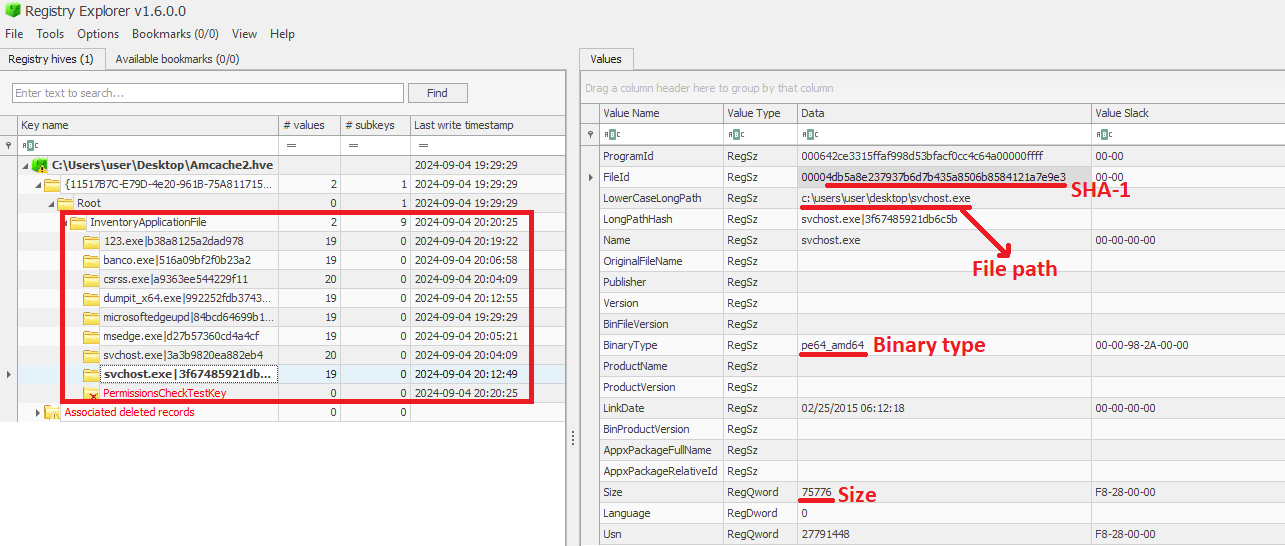

InventoryApplicationFile

The InventoryApplicationFile key is essential for tracking every executable discovered on the system. Under this key, each executable is represented by its own uniquely named subkey, which stores the following main metadata:

- ProgramId: a unique hash generated from the binary name, version, publisher, and language, with some zeroes appended to the beginning of the hash

- FileID: the SHA-1 hash of the file, with four zeroes appended to the beginning of the hash

- LowerCaseLongPath: the full lowercase path to the executable

- Name: the file base name without the path information

- OriginalFileName: the original filename as specified in the PE header’s version resource, indicating the name assigned by the developer at build time

- Publisher: often used to verify if the source of the binary is legitimate. For malware, this subkey is usually empty

- Version: the specific build or release version of the executable

- BinaryType: indicates whether the executable is a 32-bit or 64-bit binary

- ProductName: the ProductName field from the version resource, describing the broader software product or suite to which the executable belongs

- LinkDate: the compilation timestamp extracted from the PE header

- Size: the file size in bytes

- IsOsComponent: a boolean flag that specifies whether the executable is a built-in OS component or a third-party application/library

With some tweaks to our original Python parser, we can read the information stored within this key:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import sys

from Registry.Registry import Registry

hive = Registry(sys.argv[1])

root = hive.open("Root")

subs = {k.name(): k for k in root.subkeys()}

parent = subs.get("InventoryApplicationFile")

for rec in parent.subkeys():

vals = {v.name(): v.value() for v in rec.values()}

print("{}\n{}\n\n-----------\n".format(rec, vals))

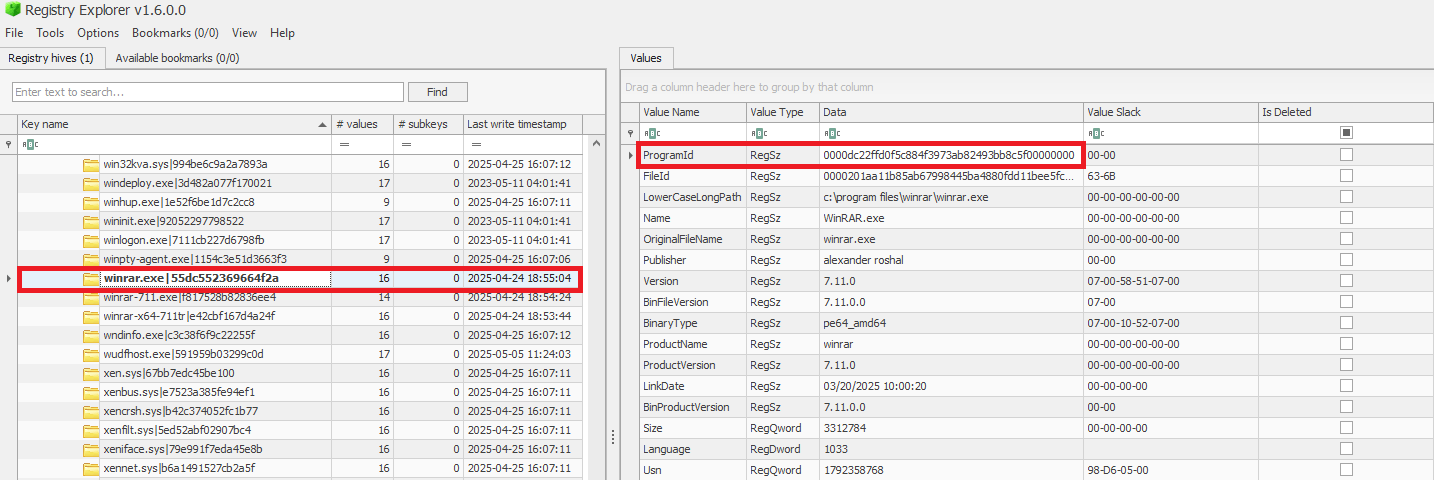

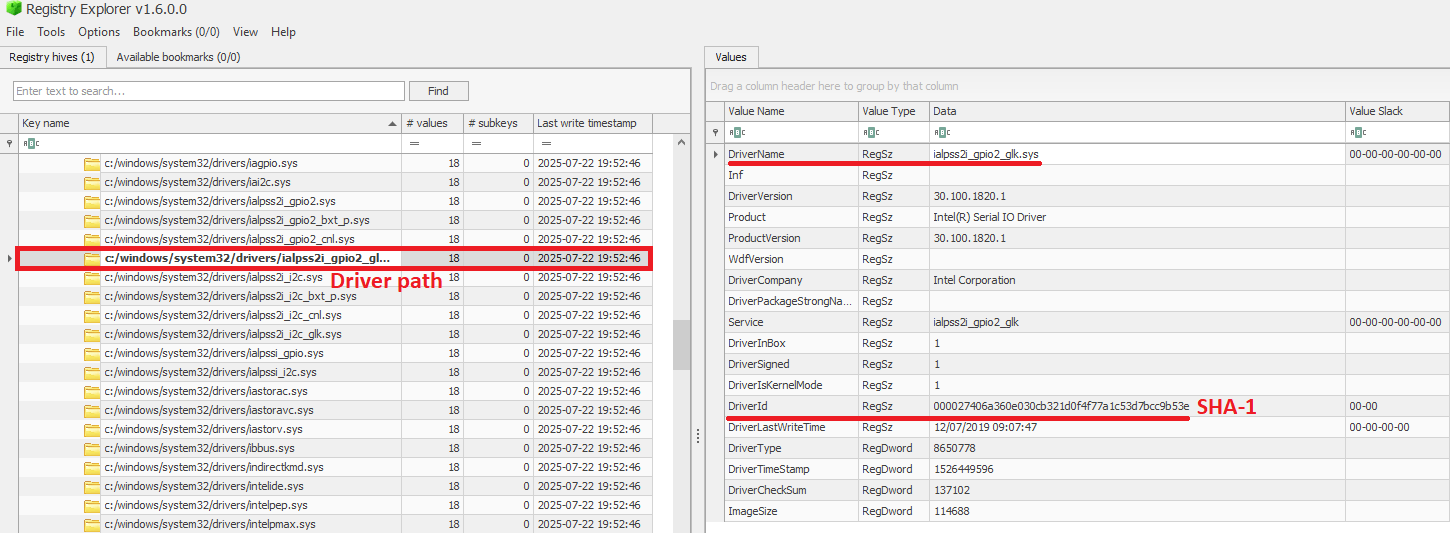

We can also use tools like Registry Explorer to see the same data in a graphical way:

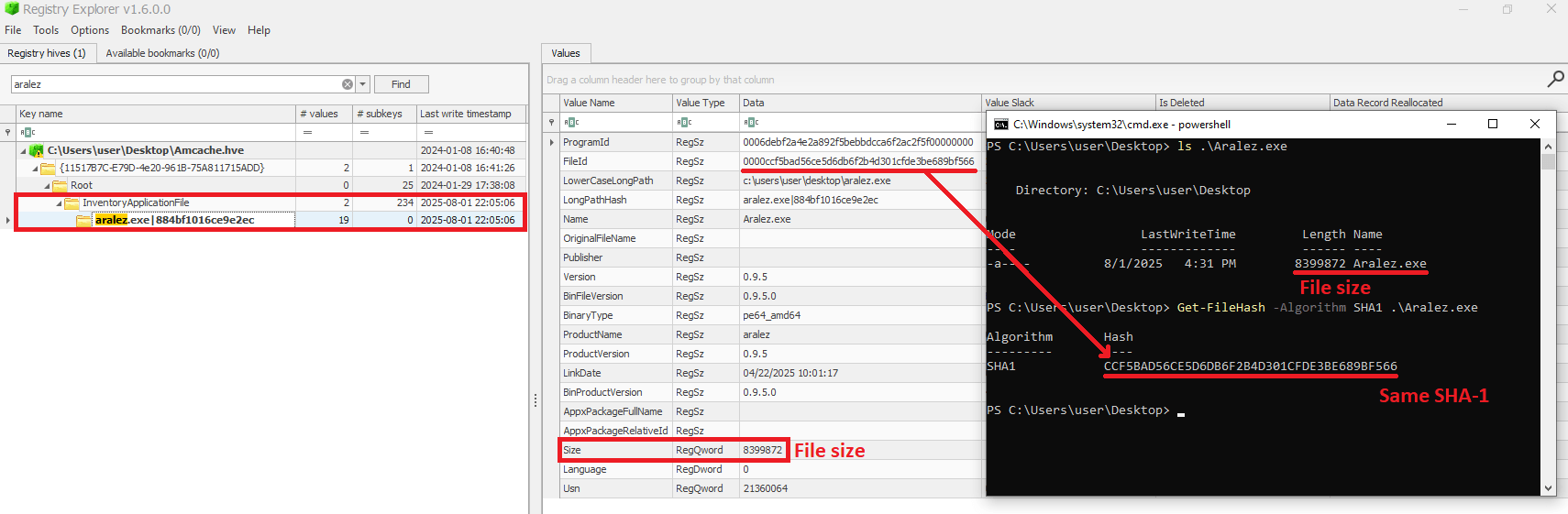

As mentioned before, AmCache computes the SHA-1 hash over only the first 31,457,280 bytes (≈31 MB). To prove this, we did a small experiment, during which we got a binary smaller than 31 MB (Aralez) and one larger than this value (a custom version of Velociraptor). For the first case, the SHA-1 hash of the entire binary was stored in AmCache.

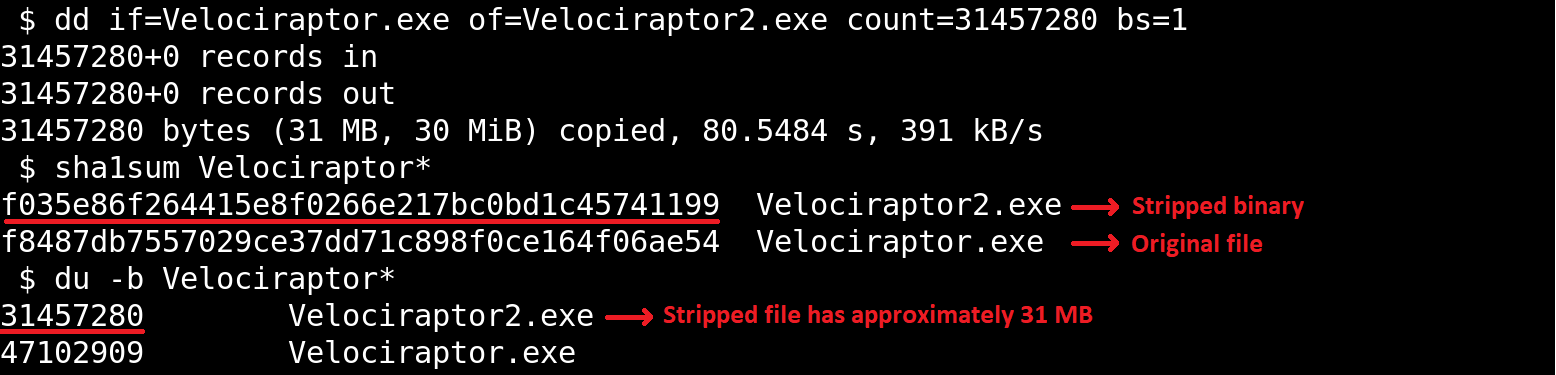

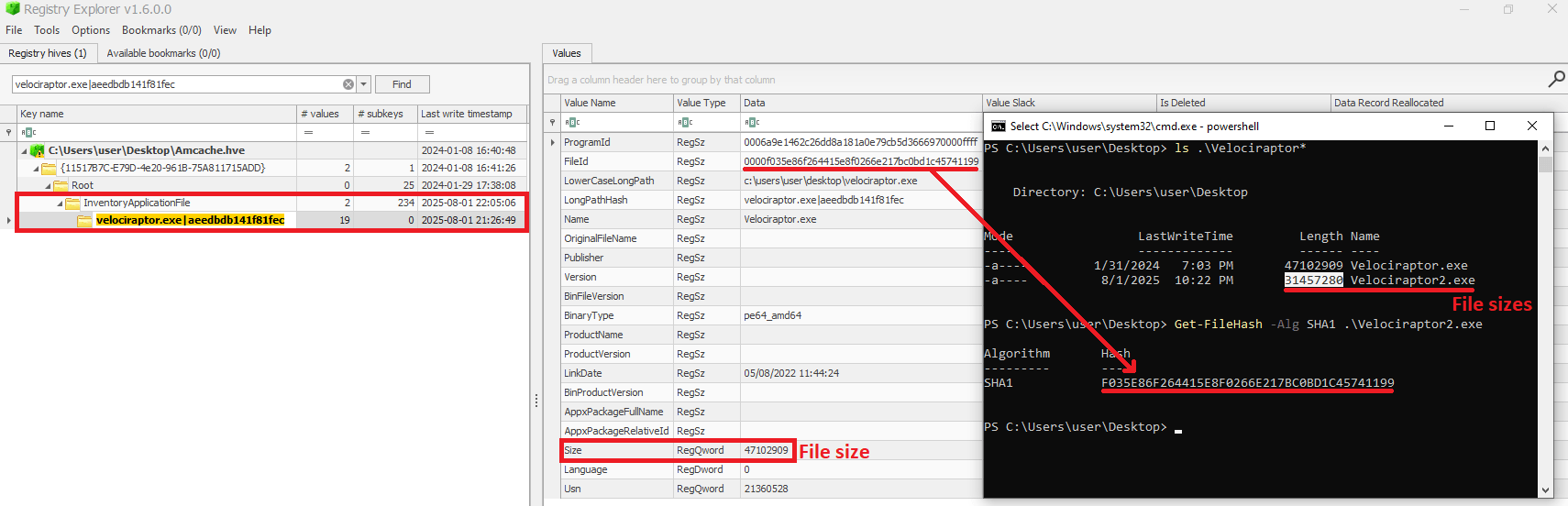

For the second scenario, we used the dd utility to extract the first 31 MB of the Velociraptor binary:

When checking the Velociraptor entry on AmCache, we found that it indeed stored the SHA-1 hash calculated only for the first 31,457,280 bytes of the binary. Interestingly enough, the Size value represented the actual size of the original file. Thus, relying only on the file hash stored on AmCache for querying threat intelligence portals may be not enough when dealing with large files. So, we need to check if the file size in the record is bigger than 31,457,280 bytes before searching threat intelligence portals.

Additionally, attackers may take advantage of this characteristic to purposely generate large malicious binaries. In this way, even if investigators find that a malware was executed/present on a Windows system, the actual SHA-1 hash of the binary will still be unknown, making it difficult to track it across the network and gathering it from public databases like VirusTotal.

InventoryApplicationFile – use case example: finding a deleted tool that was used

Let’s suppose you are searching for a possible insider threat. The user denies having run any suspicious programs, and any suspicious software was securely erased from disk. But in the InventoryApplicationFile, you find a record of winscp.exe being present in the user’s Downloads folder. Even though the file is gone, this tells you the tool was on the machine and it was likely used to transfer files before being deleted. In our incident response practice, we have seen similar cases, where this key proved useful.

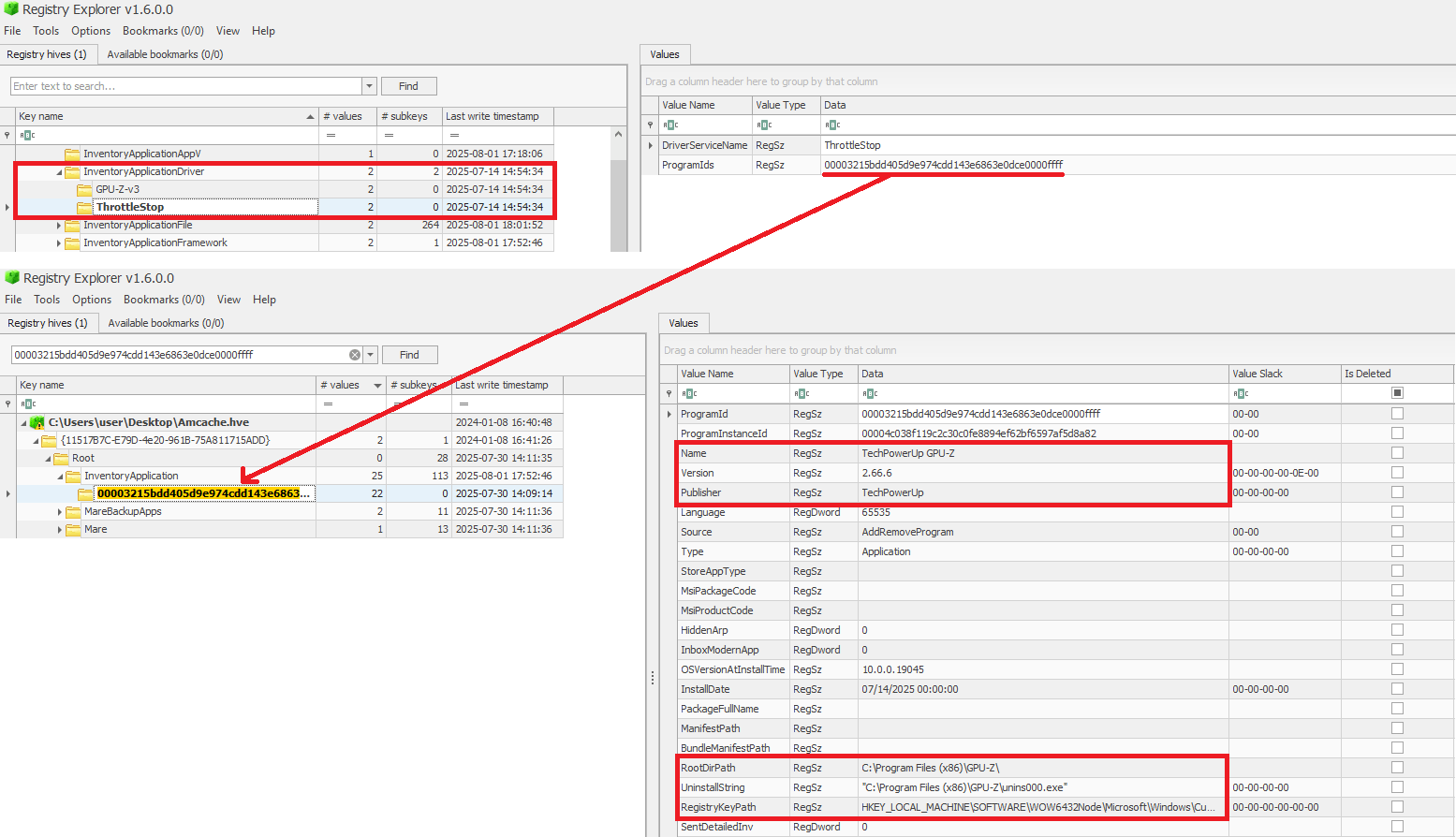

InventoryApplication

The InventoryApplication key records details about applications that were previously installed on the system. Unlike InventoryApplicationFile, which logs every executable encountered, InventoryApplication focuses on those with installation records. Each entry is named by its unique ProgramId, allowing straightforward linkage back to the corresponding InventoryApplicationFile key. Additionally, InventoryApplication has the following subkeys of interest:

- InstallDate: a date‑time string indicating when the OS first recorded or recognized the application

- MsiInstallDate: present only if installed via Windows Installer (MSI); shows the exact time the MSI package was applied, sourced directly from the MSI metadata

- UninstallString: the exact command line used to remove the application

- Language: numeric locale identifier set by the developer (LCID)

- Publisher: the name of the software publisher or vendor

- ManifestPath: the file path to the installation manifest used by UWP or AppX/MSIX apps

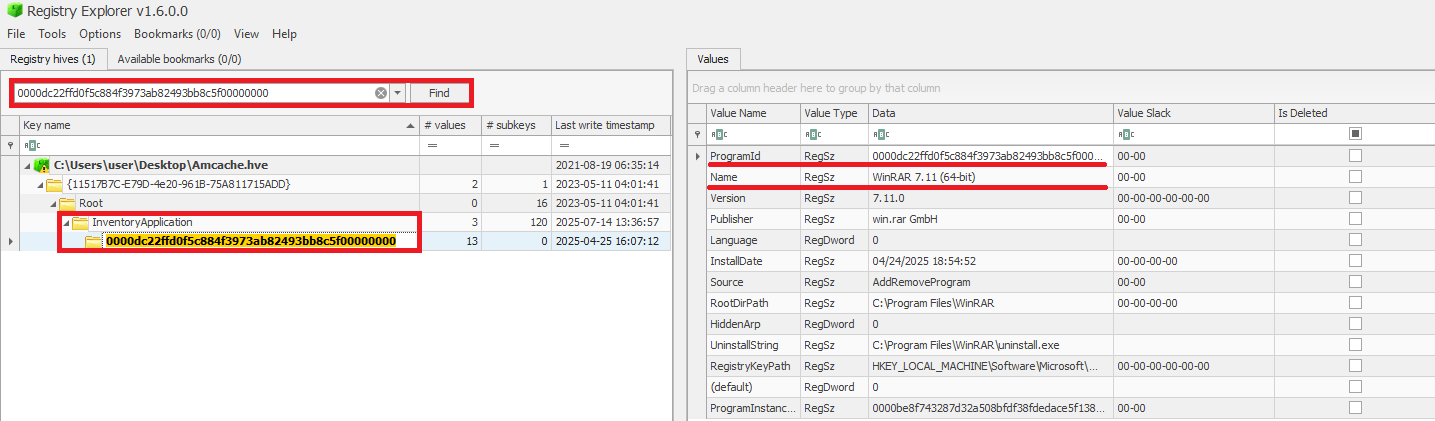

With a simple change to our parser, we can check the data contained in this key:

<...>

parent = subs.get("InventoryApplication")

<...>

When a ProgramId appears both here and under InventoryApplicationFile, it confirms that the executable is not merely present or executed, but was formally installed. This distinction helps us separate ad-hoc copies or transient executions from installed software. The following figure shows the ProgramId of the WinRAR software under InventoryApplicationFile.

When searching for the ProgramId, we find an exact match under InventoryApplication. This confirms that WinRAR was indeed installed on the system.

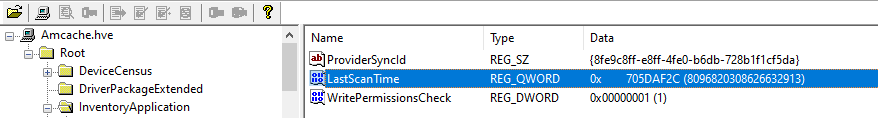

Another interesting detail about InventoryApplication is that it contains a subkey named LastScanTime, which is stored separately from ProgramIds and holds a value representing the last time the Microsoft Compatibility Appraiser ran. This is a scheduled task that launches the compattelrunner.exe binary, and the information in this key should only be updated when that task executes. As a result, software installed since the last run of the Appraiser may not appear here. The LastScanTime value is stored in Windows FileTime format.

InventoryApplication – use case example: spotting remote access software

Suppose that during an incident response engagement, you find an entry for AnyDesk in the InventoryApplication key (although the application is not installed anymore). This means that the attacker likely used it for remote access and then removed it to cover their tracks. Even if wiped from disk, this key proves it was present. We have seen this scenario in real-world cases more than once.

InventoryDriverBinary

The InventoryDriverBinary key records every kernel-mode driver that the system has loaded, providing the essential metadata needed to spot suspicious or malicious drivers. Under this key, each driver is captured in its own uniquely named subkey and includes:

- FileID: the SHA-1 hash of the driver binary, with four zeroes appended to the beginning of the hash

- LowerCaseLongPath: the full lowercase file path to the driver on disk

- DigitalSignature: the code-signing certificate details. A valid, trusted signature helps confirm the driver’s authenticity

- LastModified: the file’s last modification timestamp from the filesystem metadata, revealing when the driver binary was most recently altered on disk

Because Windows drivers run at the highest privilege level, they are frequently exploited by malware. For example, a previous study conducted by Kaspersky shows that attackers are exploiting vulnerable drivers for killing EDR processes. When dealing with a cybersecurity incident, investigators correlate each driver’s cryptographic hash, file path, signature status, and modification timestamp. That can help in verifying if the binary matches a known, signed version, detecting any tampering by spotting unexpected modification dates, and flagging unsigned or anomalously named drivers for deeper analysis. Projects like LOLDrivers help identify vulnerable drivers in use by attackers in the wild.

In addition to the InventoryDriverBinary, AmCache also provides the InventoryApplicationDriver key, which keeps track of all drivers that have been installed by specific applications. It includes two entries:

- DriverServiceName, which identifies the name of the service linked to the installed driver; and

- ProgramIds, which lists the program identifiers (corresponding to the key names under

InventoryApplication) that were responsible for installing the driver.

As shown in the figure below, the ProgramIds key can be used to track the associated program that uses this driver:

InventoryDriverBinary – use case example: catching a bad driver

If the system was compromised through the abuse of a known vulnerable or malicious driver, you can use the InventoryDriverBinary registry key to confirm its presence. Even if the driver has been removed or hidden, remnants in this key can reveal that it was once loaded, which helps identify kernel-level compromises and supporting timeline reconstruction during the investigation. This is exactly how the AV Killer malware was discovered.

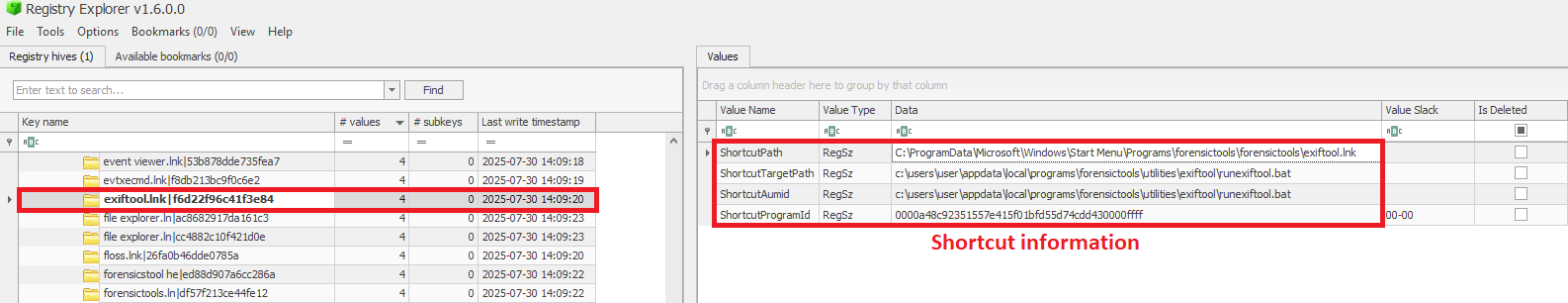

InventoryApplicationShortcut

This key contains entries for .lnk (shortcut) files that were present in folders like each user’s Start Menu or Desktop. Within each shortcut key, the ShortcutPath provides the absolute path to the LNK file at the moment of discovery. The ShortcutTargetPath shows where the shortcut pointed. We can also search for the ProgramId entry within the InventoryApplication key using the ShortcutProgramId (similar to what we did for drivers).

InventoryApplicationShortcut – use case example: confirming use of a removed app

You find that a suspicious program was deleted from the computer, but the user claims they never ran it. The InventoryApplicationShortcut key shows a shortcut to that program was on their desktop and was accessed recently. With supplementary evidence, such as that from Prefetch analysis, you can confirm the execution of the software.

AmCache key comparison

The table below summarizes the information presented in the previous subsections, highlighting the main information about each AmCache key.

| Key | Contains | Indicates execution? |

| InventoryApplicationFile | Metadata for all executables seen on the system. | Possibly (presence = likely executed) |

| InventoryApplication | Metadata about formally installed software. | No (indicates installation, not necessarily execution) |

| InventoryDriverBinary | Metadata about loaded kernel-mode drivers. | Yes (driver was loaded into memory) |

| InventoryApplicationShortcut | Information about .lnk files. | Possibly (combine with other data for confirmation) |

AmCache-EvilHunter

Undoubtedly Amcache.hve is a very important forensic artifact. However, we could not find any tool that effectively parses its contents while providing threat intelligence for the analyst. With this in mind, we developed AmCache-EvilHunter a command-line tool to parse and analyze Windows Amcache.hve registry hives, identify evidence of execution, suspicious executables, and integrate Kaspersky OpenTIP and VirusTotal lookups for enhanced threat intelligence.

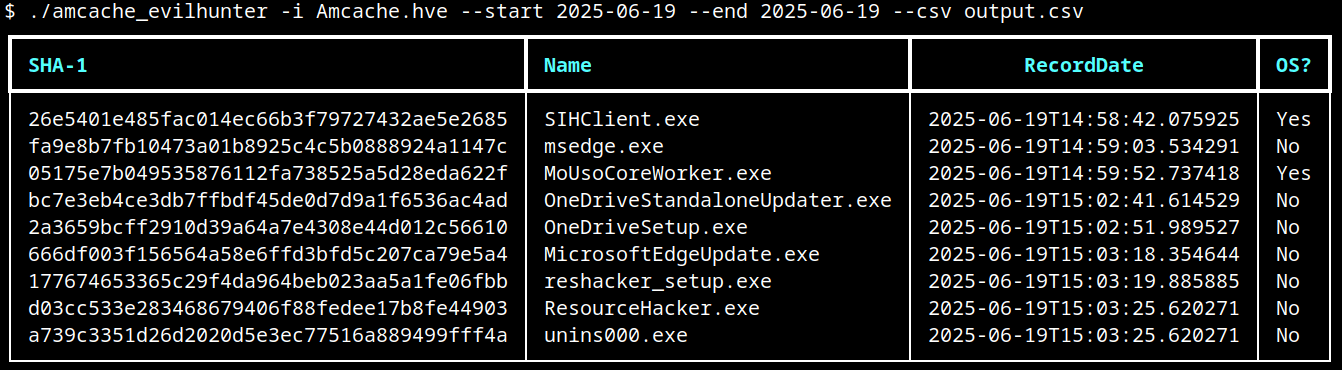

AmCache-EvilHunter is capable of processing the Amcache.hve file and filter records by date range (with the options --start and --end). It is also possible to search records using keywords (--search), which is useful for searching for known naming conventions adopted by attackers. The results can be saved in CSV (--csv) or JSON (--json) formats.

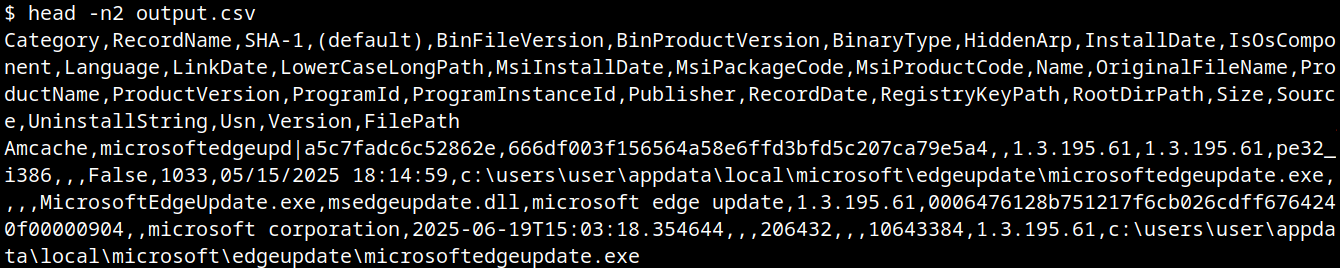

The image below shows an example of execution of AmCache-EvilHunter with these basic options, by using the following command:

amcache-evilhunter -i Amcache.hve --start 2025-06-19 --end 2025-06-19 --csv output.csv

The output contains all applications that were present on the machine on June 19, 2025. The last column contains information whether the file is an operating system component, or not.

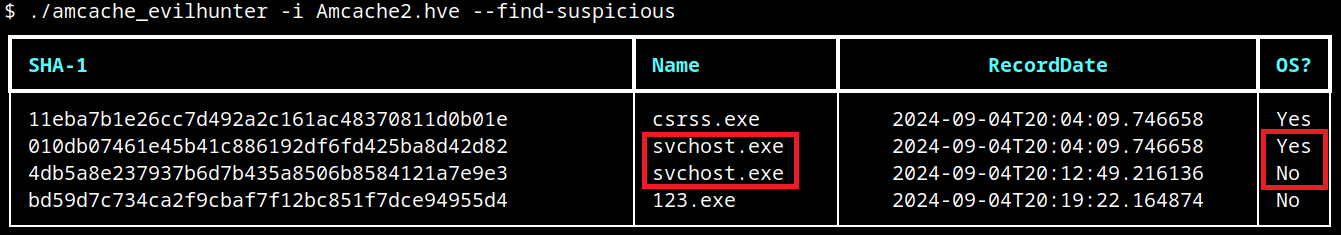

Analysts are often faced with a large volume of executables and artifacts. To narrow down the scope and reduce noise, the tool is able to search for known suspicious binaries with the --find-suspicious option. The patterns used by the tool include common malware names, Windows processes containing small typos (e.g., scvhost.exe), legitimate executables usually found in use during incidents, one-letter/one-digit file names (such as 1.exe, a.exe), or random hex strings. The figure below shows the results obtained by using this option; as highlighted, one svchost.exe file is part of the operating system and the other is not, making it a good candidate for collection and analysis if not deleted.

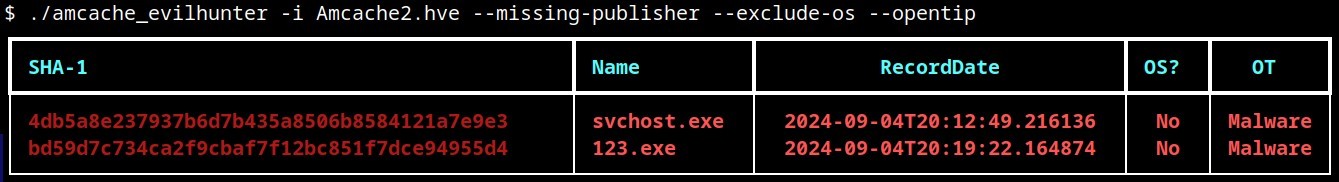

Malicious files usually do not include any publisher information and are definitely not part of the default operating system. For this reason, AmCache-EvilHunter also ships with the --missing-publisher and --exclude-os options. These parameters allow for easy filtering of suspicious binaries and also allow fast threat intelligence gathering, which is crucial during an incident.

Another important feature that distinguishes our tool from other proposed approaches is that AmCache-EvilHunter can query Kaspersky OpenTIP (--opentip ) and VirusTotal (--vt) for hashes it identifies. In this way, analysts can rapidly gain insights into samples to decide whether they are going to proceed with a full analysis of the artifact or not.

Binaries of the tool are available on our GitHub page for both Linux and Windows systems.

Conclusion

Amcache.hve is a cornerstone of Windows forensics, capturing rich metadata, such as full paths, SHA-1 hashes, compilation timestamps, publisher and version details, for every executable that appears on a system. While it does not serve as a definitive execution log, its strength lies in documenting file presence and paths, making it invaluable for spotting anomalous binaries, verifying trustworthiness via hash lookups against threat‐intelligence feeds, and correlating LinkDate values with known attack campaigns.

To extract its full investigative potential, analysts should merge AmCache data with other artifacts (e.g., Prefetch, ShimCache, and Windows event logs) to confirm actual execution and build accurate timelines. Comparing InventoryApplicationFile entries against InventoryApplication reveals whether a file was merely dropped or formally installed, and identifying unexpected driver records can expose stealthy rootkits and persistence mechanisms. Leveraging parsers like AmCache-EvilHunter and cross-referencing against VirusTotal or proprietary threat databases allows IOC generation and robust incident response, making AmCache analysis a fundamental DFIR skill.

Sentinels League: Live Rankings for the Threat Hunting World Championship

The Sentinels League is the official, week-by-week standings for the Threat Hunting World Championship – the first-of-its-kind tournament where the world’s top defenders go head-to-head across four surfaces: AI, Cloud, SIEM, and Endpoint. Thousands of blue teamers from more than 100 countries are tackling real-world attack scenarios to earn points, climb the tables, and secure their path to Las Vegas.

Bookmark this blog post to check your position, track the movement each week, and jump into the next qualifier if you’re not on the board yet.

More Than a Game | How the Sentinels League Work

Qualifiers run throughout the month of September across the four league tracks with players who finish in the top 50 in each league advancing to the Regional Finals on October 22 for the Americas, Europe, and Asia Pacific & Japan. From there, regional champions progress to the Grand Final at OneCon in Las Vegas from November 4 to 6, where the World Champion is crowned.

This is more than a game. It’s a global showdown that blends entertainment, education, and elite competition. Defenders everywhere will up-level their skills and battle for:

- $100,000 in prizes

- A championship trophy

- The prestige of being crowned World Champion

- Charitable donations made in partnership with the S Foundation on behalf of each finalist

Only one player will take home the title, but everyone gains the experience of battling in real-world scenarios that sharpen the skills cyber defenders use daily.

A Global Leaderboard in Action | Follow the League Tables Live

These games are grounded in real incidents and operational trade-offs. Players earn points for flags captured and accuracy under time limits. This means pace and precision both matter. The tables below display each player’s alias, alongside points, and the prize they would receive should they finish in that same position.

Qualifying Stages

Compete online from anywhere, or in-person at select events this month. Earn Threat Hunting Hero badges, prizes, and points that advance you up the league tables. Throughout September, players may enter once per qualifier and compete across all four tracks.

- AI Qualifier Games: Take on scenarios featuring AI attackers and AI-powered threat hunting tools.

- Cloud Qualifier Games: Track and neutralize threats across cloud-based attack surfaces.

- SIEM Qualifier Games: Assert your dominance in real-time SIEM hunting and remediation challenges.

- Endpoint Qualifier Games: Hunt down and remediate endpoint vulnerabilities in scenarios pulled straight from real-world incidents.

Regional Finals | October 22

The top 200 players from each region (Americas, Europe, Asia Pacific & Japan) will face off live in an action-packed online event. Only three regional champions will advance.

Grand Final | November 4–6 | OneCon, Las Vegas

Three finalists will earn an all-expenses-paid trip to OneCon 2025 in Las Vegas to compete live on stage for the World Championship title, the trophy, and the $100K prize pool.

Leagues Menu Quick Jump

AI Leagues

Live table for the AI League Qualifiers are as follows. Top 50 on October 2 qualify for the Regional Finals.

AI APJ League

| Rank | Alias | Score | Prize |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sean | 4800 | $2,000 + Entry |

| 2 | Gon | 4800 | $1,200 + Entry |

| 3 | Hyena | 4800 | $800 + Entry |

| 4 | 0xDariusNG | 4800 | $500 + Entry |

| 5 | PHEAKRO | 4780 | Entry |

| 6 | 0xKowloon | 4780 | Entry |

| 7 | Mingi | 4780 | $500 + Entry |

| 8 | injun | 4760 | $500 + Entry |

| 9 | cameronpaddyTL | 4740 | $500 + Entry |

| 10 | donghyeok | 4740 | $500 + Entry |

| 11 | Gowda | 4730 | Entry |

| 12 | kerostic | 4700 | Entry |

| 13 | Absol | 4700 | Entry |

| 14 | NotFound | 4700 | Entry |

| 15 | Jay | 4700 | Entry |

| 16 | Anonghost | 4700 | Entry |

| 17 | Siwoo | 4680 | Entry |

| 18 | qutypie | 4680 | Entry |

| 19 | AAA | 4680 | Entry |

| 20 | avynilite | 4680 | Entry |

| 21 | Shawn_Kwak | 4660 | Entry |

| 22 | ouoaaa | 4660 | Entry |

| 23 | N-dawg | 4660 | Entry |

| 24 | Johncena | 4660 | Entry |

| 25 | haon | 4660 | Entry |

| 26 | matrix | 4660 | Entry |

| 27 | meowfoobar | 4640 | Entry |

| 28 | bheda | 4640 | Entry |

| 29 | host | 4600 | Entry |

| 30 | weeknd | 4550 | Entry |

| 31 | davkjp | 4500 | Entry |

| 32 | ThreatAnalystX | 4500 | Entry |

| 33 | clerkofcourse | 4500 | Entry |

| 34 | Sujin | 4500 | Entry |

| 35 | heogi | 4400 | Entry |

| 36 | gwthm01 | 4400 | Entry |

| 37 | elesh27 | 4240 | Entry |

| 38 | 1-1063 | 4160 | Entry |

| 39 | mohan | 4150 | Entry |

| 40 | haysia-aml | 3980 | Entry |

| 41 | SmolAME | 3960 | Entry |

| 42 | riz_wan | 3920 | Entry |

| 43 | Ninja | 3860 | Entry |

| 44 | Paul-NZ | 3760 | Entry |

| 45 | dinnershow | 3700 | Entry |

| 46 | aaditya_khandke | 3680 | Entry |

| 47 | sanalk | 3660 | Entry |

| 48 | Gibbo | 3600 | Entry |

| 49 | Nisanak | 3520 | Entry |

| 50 | weeknd | 3460 | Entry |

AI EMEA League

| Rank | Alias | Score | Prize |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ELL | 4800 | $2,000 + Entry |

| 2 | Andy | 4800 | $1,200 + Entry |

| 3 | Krzysztof | 4800 | Entry |

| 4 | christopher | 4800 | $500 + Entry |

| 5 | HermessNRJ | 4800 | $500 + Entry |

| 6 | jodie | 4800 | $500 + Entry |

| 7 | Arnau | 4800 | $500 + Entry |

| 8 | Fenio2 | 4800 | $500 + Entry |

| 9 | imouse | 4800 | Entry |

| 10 | TristanA | 4800 | $500 + Entry |

| 11 | SSman | 4800 | Entry |

| 12 | nicpooon | 4800 | Entry |

| 13 | goksara01 | 4800 | Entry |

| 14 | TomEdwards | 4800 | Entry |

| 15 | msnaydenov | 4800 | Entry |

| 16 | mrdiSec | 4800 | Entry |

| 17 | Kurty | 4800 | Entry |

| 18 | HackNSeek | 4780 | Entry |

| 19 | SEnev | 4780 | Entry |

| 20 | Plissken | 4780 | Entry |

| 21 | mka | 4780 | Entry |

| 22 | Ptikek | 4780 | Entry |

| 23 | Chris | 4780 | Entry |

| 24 | stahl | 4780 | Entry |

| 25 | D1vy | 4780 | Entry |

| 26 | alexcohen | 4780 | Entry |

| 27 | Krxsx | 4780 | Entry |

| 28 | hemalsoni22 | 4780 | Entry |

| 29 | bytesize | 4780 | Entry |

| 30 | manthan1501 | 4780 | Entry |

| 31 | buttercup6789 | 4780 | Entry |

| 32 | CBVirus | 4780 | Entry |

| 33 | Kamil7cd | 4760 | Entry |

| 34 | Pikachu | 4760 | Entry |

| 35 | krysix | 4760 | Entry |

| 36 | gandalf | 4760 | Entry |

| 37 | Parshwa | 4760 | Entry |

| 38 | P1ckl3 | 4760 | Entry |

| 39 | DenRubai | 4740 | Entry |

| 40 | A380 | 4740 | Entry |

| 41 | alwayshungry | 4740 | Entry |

| 42 | xdoubtful | 4720 | Entry |

| 43 | Sunny59 | 4720 | Entry |

| 44 | AJ56 | 4700 | Entry |

| 45 | nobody27 | 4680 | Entry |

| 46 | bluephish | 4680 | Entry |

| 47 | Kalilee | 4660 | Entry |

| 50 | ft44k | 4380 | Entry |

AI AMERICAS League

| Rank | Alias | Score | Prize |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | eforsha | 4800 | $2,000 + Entry |

| 2 | Thomas | 4800 | $1,200 + Entry |

| 3 | 1-2-3-4 | 4800 | $800 + Entry |

| 4 | AU1 | 4800 | $500 + Entry |

| 5 | Survivor4Ever | 4800 | $500 + Entry |

| 6 | NightHammer | 4800 | $500 + Entry |

| 7 | ZachsAlt | 4800 | $500 + Entry |

| 8 | Romulus | 4800 | $500 + Entry |

| 9 | pmchale | 4800 | $500 + Entry |

| 10 | ByKroo | 4800 | Entry |

| 11 | kquirosf102 | 4800 | Entry |

| 12 | JConatus | 4800 | Entry |

| 13 | bwillhelm | 4800 | Entry |

| 14 | jasonmull | 4800 | Entry |

| 15 | ThreatSlayer | 4800 | Entry |

| 16 | james | 4800 | Entry |

| 17 | JayHole | 4800 | Entry |

| 18 | capnjack | 4800 | Entry |

| 19 | mainasara | 4800 | Entry |

| 20 | Sil3nt_gh0st | 4800 | Entry |

| 21 | RakeshN | 4800 | Entry |

| 22 | ninjacat | 4800 | Entry |

| 23 | jswiegele | 4800 | Entry |

| 24 | Max | 4780 | Entry |

| 25 | nkoester | 4780 | Entry |

| 26 | benthehen100 | 4780 | Entry |

| 27 | nok0 | 4780 | Entry |

| 28 | max | 4780 | Entry |

| 29 | Dani | 4780 | Entry |

| 30 | testuser | 4780 | Entry |

| 31 | mprof | 4780 | Entry |

| 32 | caputdraconis | 4780 | Entry |

| 33 | colsaBoys | 4780 | Entry |

| 34 | Endlaze | 4780 | Entry |

| 35 | littymac | 4780 | Entry |

| 36 | jlytle | 4780 | Entry |

| 37 | ana7z | 4780 | Entry |

| 38 | mkilp | 4780 | Entry |

| 39 | ComradePanda | 4780 | Entry |

| 40 | SHWON | 4760 | Entry |

| 41 | s-swift | 4760 | Entry |

| 42 | sickstick | 4760 | Entry |

| 43 | David_S | 4760 | Entry |

| 44 | EchoNight | 4760 | Entry |

| 45 | gg88gg99 | 4760 | Entry |

| 46 | rtovell | 4760 | Entry |

| 47 | saberwolf617 | 4745 | Entry |

| 48 | alevine | 4740 | Entry |

| 49 | enleak | 4740 | Entry |

| 50 | ahmad | 4740 | Entry |

Back to the Menu Quick Jump

Cloud Leagues

Live table for the Cloud League Qualifiers are as follows. Top 50 on October 2 qualify for the Regional Finals.

Cloud APJ League

| Rank | Alias | Score | Prize |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NotFound | 3900 | $2,000 + Entry |

| 2 | Sean | 3900 | $1,200 + Entry |

| 3 | Shawn_Kwak | 3900 | $800 + Entry |

| 4 | Absol | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 5 | Salmon-Mia | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 6 | injun | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 7 | Gon | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 8 | Hyena | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 9 | donghyeok | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 10 | Minyoung | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 11 | 1stTimer | 3900 | Entry |

| 12 | HoumanD | 3900 | Entry |

| 13 | mastoto | 3900 | Entry |

| 14 | Jim | 3900 | Entry |

| 15 | gwthm01 | 3900 | Entry |

| 16 | cyrusmehra | 3900 | Entry |

| 17 | kerostic | 3880 | Entry |

| 18 | 0xDariusNG | 3880 | Entry |

| 19 | Jay | 3880 | Entry |

| 20 | ouoaaa | 3880 | Entry |

| 21 | pgpt | 3880 | Entry |

| 22 | HNVN | 3880 | Entry |

| 23 | TI-MG | 3880 | Entry |

| 24 | weeknd | 3880 | Entry |

| 25 | Bolito687 | 3880 | Entry |

| 26 | Sujin | 3880 | Entry |

| 27 | Siwoo | 3860 | Entry |

| 28 | Johncena | 3860 | Entry |

| 29 | Nisanak | 3860 | Entry |

| 30 | 1-1063 | 3860 | Entry |

| 31 | Ketsui | 3860 | Entry |

| 32 | clerkofcourse | 3850 | Entry |

| 33 | wliu | 3840 | Entry |

| 34 | heogi | 3820 | Entry |

| 35 | usrbin | 3820 | Entry |

| 36 | SmolAME | 3810 | Entry |

| 37 | qutypie | 3800 | Entry |

| 38 | quifl | 3800 | Entry |

| 39 | avynilite | 3770 | Entry |

| 40 | sanketsalve | 3760 | Entry |

| 41 | r00t | 3750 | Entry |

| 42 | ctrlmurray | 3740 | Entry |

| 43 | Dia | 3680 | Entry |

| 44 | Gowda | 3460 | Entry |

| 45 | skkcyb3r | 3390 | Entry |

| 46 | ezhunt | 3080 | Entry |

| 47 | jeba | 2740 | Entry |

| 48 | josep | 2720 | Entry |

| 49 | pincode | 2700 | Entry |

| 50 | Shiva | 2660 | Entry |

Cloud EMEA League

| Rank | Alias | Score | Prize |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ELL | 3900 | $2,000 + Entry |

| 2 | french_taco | 3900 | $1,200 + Entry |

| 3 | jodie | 3900 | $800 + Entry |

| 4 | Revil | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 5 | EthicalPetal | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 6 | hemalsoni22 | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 7 | Krish | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 8 | Parshwa | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 9 | D1vy | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 10 | HermessNRJ | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 11 | mka | 3900 | Entry |

| 12 | ah01 | 3900 | Entry |

| 13 | tomkerswill | 3900 | Entry |

| 14 | demisto | 3900 | Entry |

| 15 | P3ngu1nB3er | 3900 | Entry |

| 16 | Arnau | 3880 | Entry |

| 17 | A380 | 3880 | Entry |

| 18 | Lennard | 3880 | Entry |

| 19 | Fenio | 3880 | Entry |

| 20 | manthan1501 | 3880 | Entry |

| 21 | imouse | 3880 | Entry |

| 22 | rado-van | 3880 | Entry |

| 23 | MrHokage | 3880 | Entry |

| 24 | guin | 3880 | Entry |

| 25 | Duall | 3880 | Entry |

| 26 | jamesthor | 3880 | Entry |

| 27 | Dhara23 | 3870 | Entry |

| 28 | christopher | 3860 | Entry |

| 29 | moon77 | 3860 | Entry |

| 30 | eniz | 3860 | Entry |

| 31 | Oscar_G | 3860 | Entry |

| 32 | dcpl | 3860 | Entry |

| 33 | htue | 3860 | Entry |

| 34 | sug4r-wr41th | 3840 | Entry |

| 35 | modeus | 3840 | Entry |

| 36 | blackhat | 3840 | Entry |

| 37 | xdoubtful | 3840 | Entry |

| 38 | CBVirus | 3840 | Entry |

| 39 | Plissken | 3840 | Entry |

| 40 | Igor | 3840 | Entry |

| 41 | StijnG | 3820 | Entry |

| 42 | RDx | 3820 | Entry |

| 43 | JohnMatrix | 3820 | Entry |

| 44 | Ptikek | 3820 | Entry |

| 45 | Kalilee | 3800 | Entry |

| 46 | canigetabeepbeep | 3780 | Entry |

| 47 | SilentPursuit | 3780 | Entry |

| 48 | nobody27 | 3780 | Entry |

| 49 | Drako | 3770 | Entry |

| 50 | desidosa | 3760 | Entry |

Cloud AMERICAS League

| Rank | Alias | Score | Prize |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Stephen | 3900 | $2,000 + Entry |

| 2 | Honu | 3900 | Entry |

| 3 | AU1 | 3900 | $800 + Entry |

| 4 | Red-Beard | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 5 | Thomas | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 6 | 1-2-3-4 | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 7 | nmkoester | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 8 | bwillhelm | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 9 | WilliamMailhot | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 10 | alevine | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 11 | eforsha | 3900 | Entry |

| 12 | GenericAll | 3900 | Entry |

| 13 | threathunting123 | 3900 | Entry |

| 14 | benthehen100 | 3900 | Entry |

| 15 | Cwallis | 3900 | Entry |

| 16 | Joshua_Knight | 3900 | Entry |

| 17 | JacobL | 3900 | Entry |

| 18 | josh_24v_15 | 3900 | Entry |

| 19 | james | 3900 | Entry |

| 20 | maverick | 3900 | Entry |

| 21 | Hunter53 | 3900 | Entry |

| 22 | tessah_k | 3900 | Entry |

| 23 | Wisdom1k | 3900 | Entry |

| 24 | riskybusiness | 3900 | Entry |

| 25 | rpatrick | 3900 | Entry |

| 26 | wizard113 | 3900 | Entry |

| 27 | Dr_Ew | 3900 | Entry |

| 28 | Survivor4Ever | 3900 | Entry |

| 29 | BGrad | 3900 | Entry |

| 30 | 0x626d | 3900 | Entry |

| 31 | _operator | 3900 | Entry |

| 32 | oj_cup | 3900 | Entry |

| 33 | ThreatSlayer | 3900 | Entry |

| 34 | Seasalt | 3900 | Entry |

| 35 | daswon | 3880 | Entry |

| 36 | dwest | 3880 | Entry |

| 37 | mprof | 3880 | Entry |

| 38 | Dani | 3880 | Entry |

| 39 | hue | 3880 | Entry |

| 40 | ZachsAlt | 3880 | Entry |

| 41 | flipyaforreal | 3880 | Entry |

| 42 | jswisher | 3880 | Entry |

| 43 | gary | 3880 | Entry |

| 44 | ana7z | 3880 | Entry |

| 45 | DefenderA | 3880 | Entry |

| 46 | Avlyssna | 3880 | Entry |

| 47 | JayHole | 3880 | Entry |

| 48 | Max | 3880 | Entry |

| 49 | TheExemplar | 3880 | Entry |

| 50 | eDak | 3880 | Entry |

Back to the Menu Quick Jump

SIEM Leagues

Live table for the SIEM League Qualifiers are as follows. Top 50 on October 2 qualify for the Regional Finals.

SIEM APJ League

| Rank | Alias | Score | Prize |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jay | 4100 | $2,000 + Entry |

| 2 | Sean | 4100 | $1,200 + Entry |

| 3 | ouoaaa | 4100 | $800 + Entry |

| 4 | injun | 4100 | $500 + Entry |

| 5 | Hyena | 4100 | $500 + Entry |

| 6 | 0xKowloon | 4100 | Entry |

| 7 | Gon | 4080 | $500 + Entry |

| 8 | NotFound | 4080 | $500 + Entry |

| 9 | drake | 3980 | $500 + Entry |

| 10 | Johncena | 3820 | $500 + Entry |

| 11 | Absol | 3800 | Entry |

| 12 | Shawn_Kwak | 3800 | Entry |

| 13 | Bolito687 | 3800 | Entry |

| 14 | heogi | 3780 | Entry |

| 15 | kerostic | 3760 | Entry |

| 16 | Mingi | 3720 | Entry |

| 17 | 1stTimer | 3680 | Entry |

| 18 | ctrlmurray | 3680 | Entry |

| 19 | avynilite | 3660 | Entry |

| 20 | Tape_Dispenser | 3600 | Entry |

| 21 | AgentMrX | 3600 | Entry |

| 22 | Duckduck | 3580 | Entry |

| 23 | SteveM | 3540 | Entry |

| 24 | Minyoung | 3500 | Entry |

| 25 | GCTDLover | 3500 | Entry |

| 26 | Salmon-Mia | 3480 | Entry |

| 27 | HYEOK | 3480 | Entry |

| 28 | Siwoo | 3440 | Entry |

| 29 | gwthm01 | 3440 | Entry |

| 30 | Sujin | 3440 | Entry |

| 31 | SmolAME | 3400 | Entry |

| 32 | 1-1063 | 3320 | Entry |

| 33 | host | 3200 | Entry |

| 34 | Ketsui | 3200 | Entry |

| 35 | 0xDariusNG | 3200 | Entry |

| 36 | tianred | 3180 | Entry |

| 37 | 1stTimer | 3180 | Entry |

| 38 | Anusthika | 3020 | Entry |

| 39 | null_faruq | 2780 | Entry |

| 40 | ace | 2760 | Entry |

| 41 | usrbin | 2680 | Entry |

| 42 | haysia-aml | 2660 | Entry |

| 43 | MooH | 2660 | Entry |

| 44 | CTF_threathunt9 | 2660 | Entry |

| 45 | clerkofcourse | 2640 | Entry |

| 46 | quifl | 2640 | Entry |

| 47 | shreyas | 2620 | Entry |

| 48 | hardikjain | 2580 | Entry |

| 49 | Genie | 2580 | Entry |

| 50 | Dastr0 | 2560 | Entry |

SIEM AMERICAS League

| Rank | Alias | Score | Prize |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Red-Beard | 4100 | $2,000 + Entry |

| 2 | Romulus | 4100 | $1,200 + Entry |

| 3 | Survivor4Ever | 4100 | $800 + Entry |

| 4 | nok0 | 4000 | $500 + Entry |

| 5 | staas | 4000 | $500 + Entry |

| 6 | Sneha | 3960 | $500 + Entry |

| 7 | ninjascout_ii | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 8 | CmdnControl | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 9 | 1-2-3-4 | 3880 | $500 + Entry |

| 10 | post | 3880 | $500 + Entry |

| 11 | ZachsAlt | 3880 | Entry |

| 12 | jqueso | 3860 | Entry |

| 13 | rzv | 3840 | Entry |

| 14 | zero_cool | 3780 | Entry |

| 15 | SHWON | 3740 | Entry |

| 16 | m4lwhere | 3700 | Entry |

| 17 | rutvij2811 | 3700 | Entry |

| 18 | spelosi | 3680 | Entry |

| 19 | mp-549228 | 3640 | Entry |

| 20 | TheExemplar | 3620 | Entry |

| 21 | Max | 3600 | Entry |

| 22 | AU1 | 3580 | Entry |

| 23 | Sil3nt_gh0st | 3580 | Entry |

| 24 | Kizzmit | 3580 | Entry |

| 25 | mprof | 3500 | Entry |

| 26 | jasonmull | 3500 | Entry |

| 27 | riskybusiness | 3480 | Entry |

| 28 | Tester123 | 3480 | Entry |

| 29 | oj_cup | 3480 | Entry |

| 30 | noobpro | 3460 | Entry |

| 31 | eforsha | 3440 | Entry |

| 32 | french_taco | 3400 | Entry |

| 33 | Hacker | 3400 | Entry |

| 34 | Linus | 3400 | Entry |

| 35 | heringfish | 3400 | Entry |

| 36 | malik | 3400 | Entry |

| 37 | cyberpanda | 3400 | Entry |

| 38 | Dani | 3380 | Entry |

| 39 | LindzerBeamz | 3340 | Entry |

| 40 | Diasum | 3300 | Entry |

| 41 | NotTotallyHere | 3300 | Entry |

| 42 | dwest | 3300 | Entry |

| 43 | alevine | 3300 | Entry |

| 44 | james | 3300 | Entry |

| 45 | pgruntkowski | 3300 | Entry |

| 46 | ninjacat | 3280 | Entry |

| 47 | 4thelulz1 | 3280 | Entry |

| 48 | eDak | 3280 | Entry |

| 49 | OptimalNaptime | 3200 | Entry |

| 50 | Tony_Willey27 | 3200 | Entry |

SIEM EMEA League

| Rank | Alias | Score | Prize |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Arnau | 3980 | $2,000 + Entry |

| 2 | acassano | 3900 | $1,200 + Entry |

| 3 | tocj | 3900 | $800 + Entry |

| 4 | JoeS | 3900 | $500 + Entry |

| 5 | carlosgomez | 3880 | $500 + Entry |

| 6 | demisto | 3880 | $500 + Entry |

| 7 | RDx | 3880 | Entry |

| 8 | jodie | 3860 | $500 + Entry |

| 9 | Pinax | 3860 | $500 + Entry |

| 10 | Chris | 3860 | $500 + Entry |

| 11 | Fenio | 3860 | Entry |

| 12 | desidosa | 3840 | Entry |

| 13 | mka | 3800 | Entry |

| 14 | Nirmit | 3800 | Entry |

| 15 | SSman | 3780 | Entry |

| 16 | karasek | 3780 | Entry |

| 17 | blackhat | 3760 | Entry |

| 18 | Kamil7cd | 3740 | Entry |

| 19 | rado-van | 3700 | Entry |

| 20 | Pst | 3700 | Entry |

| 21 | tomkerswill | 3700 | Entry |

| 22 | Mzk00 | 3680 | Entry |

| 23 | ALDX | 3620 | Entry |

| 24 | mtekbicak | 3580 | Entry |

| 25 | modeus | 3560 | Entry |

| 26 | andresitoo | 3540 | Entry |

| 27 | eniz | 3540 | Entry |

| 28 | DenRubai | 3540 | Entry |

| 29 | StijnG | 3500 | Entry |

| 30 | HackNSeek | 3500 | Entry |

| 31 | Plissken | 3480 | Entry |

| 32 | m3m3kritis | 3460 | Entry |

| 33 | trashclutch | 3460 | Entry |

| 34 | Dante | 3440 | Entry |

| 35 | DFJ | 3420 | Entry |

| 36 | __zCK | 3340 | Entry |

| 37 | alwayshungry | 3320 | Entry |

| 38 | seclingua | 3260 | Entry |

| 39 | ronald_mcdonald | 3260 | Entry |

| 40 | mara-deva | 3180 | Entry |

| 41 | ABogdan | 3160 | Entry |

| 42 | icheptrosu | 3160 | Entry |

| 43 | MrMurkl | 3160 | Entry |

| 44 | TristanA | 3040 | Entry |

| 45 | h4ckm4estro | 2920 | Entry |

| 46 | gen_kai | 2880 | Entry |

| 47 | Dani | 2860 | Entry |

| 48 | Graf | 2800 | Entry |

| 49 | hipparcos | 2760 | Entry |

| 50 | Bilal | 2740 | Entry |

Back to the Menu Quick Jump

Endpoint Leagues

Live table for the Endpoint League Qualifiers are as follows. Top 50 on October 2 qualify for the Regional Finals.

Endpoint APJ League

| Rank | Alias | Score | Prize |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Salmon-Mia | 6100 | $2,000 + Entry |

| 2 | Jay | 6100 | $1,200 + Entry |

| 3 | ouoaaa | 6100 | $800 + Entry |

| 4 | Sean | 6100 | $500 + Entry |

| 5 | INTfinityBeyond | 6100 | $500 + Entry |

| 6 | tanjiro | 6100 | $500 + Entry |

| 7 | Tape_Dispenser | 6100 | $500 + Entry |

| 8 | Duckduck | 6100 | $500 + Entry |

| 9 | GCTDLover | 6100 | $500 + Entry |

| 10 | PrincessLeia | 6100 | $500 + Entry |

| 11 | injigi | 6100 | Entry |

| 12 | Hyena | 6100 | Entry |

| 13 | heogi | 6100 | Entry |

| 14 | HYEOK | 6100 | Entry |

| 15 | NotFound | 6100 | Entry |

| 16 | ctrlmurray | 6100 | Entry |

| 17 | 0xDariusNG | 6100 | Entry |

| 18 | Minyoung | 6100 | Entry |

| 19 | v_chips | 6100 | Entry |

| 20 | Muhammed | 6100 | Entry |

| 21 | avynilite | 6080 | Entry |

| 22 | ana | 6080 | Entry |

| 23 | nilnocnil | 6080 | Entry |

| 24 | jstanINTern | 6060 | Entry |

| 25 | Johncena | 6060 | Entry |

| 26 | matrix | 6060 | Entry |

| 27 | Siwoo | 6060 | Entry |

| 28 | DemetrianTitus | 6050 | Entry |

| 29 | kerostic | 6050 | Entry |

| 30 | BobCrusader | 6040 | Entry |

| 31 | pgpt | 6000 | Entry |

| 32 | SmolAME | 6000 | Entry |

| 33 | haszayan | 5990 | Entry |

| 34 | jsil | 5990 | Entry |

| 35 | JasonPhang98 | 5930 | Entry |

| 36 | MPrin | 5920 | Entry |

| 37 | null_faruq | 5900 | Entry |

| 38 | MooH | 5870 | Entry |

| 39 | clerkofcourse | 5850 | Entry |

| 40 | Anusthika | 5810 | Entry |

| 41 | JimmyJames007 | 5780 | Entry |

| 42 | drake | 5780 | Entry |

| 43 | l3Iadk | 5670 | Entry |

| 44 | tigerkali | 5650 | Entry |

| 45 | gwthm01 | 5580 | Entry |

| 46 | Anonghost | 5560 | Entry |

| 47 | ZKAD00SH | 5550 | Entry |

| 48 | Sujin | 5540 | Entry |

| 49 | Gowda | 5510 | Entry |

| 50 | qutypie | 5360 | Entry |

Endpoint AMERICAS League

| Rank | Alias | Score | Prize |

|---|---|---|---|