The Miracle of Color TV

We’ve often said that some technological advancements seemed like alien technology for their time. Sometimes we look back and think something would be easy until we realize they didn’t have the tools we have today. One of the biggest examples of this is how, in the 1950s, engineers created a color image that still plays on a black-and-white set, with the color sets also able to receive the old signals. [Electromagnetic Videos] tells the tale. The video below simulates various video artifacts, so you not only learn about the details of NTSC video, but also see some of the discussed effects in real time.

Creating a black-and-white signal was already a big deal, with the video and sync presented in an analog AM signal with the sound superimposed with FM. People had demonstrated color earlier, but it wasn’t practical for several reasons. Sending, for example, separate red, blue, and green signals would require wider channels and more complex receivers, and would be incompatible with older sets.

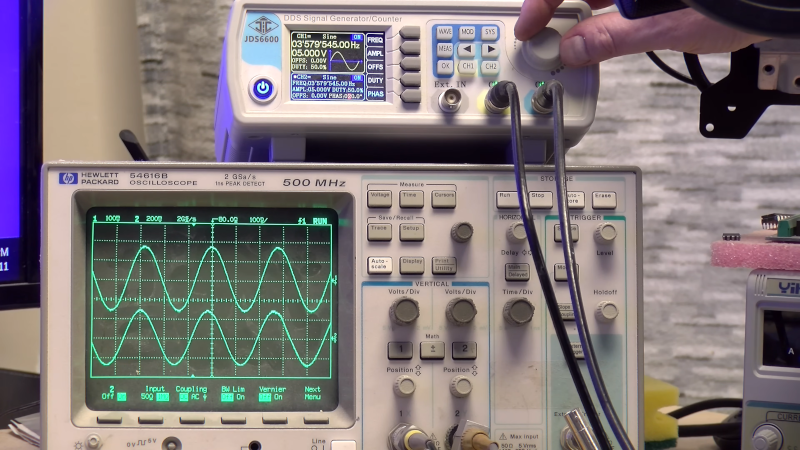

The trick, at least for the NTSC standard, was to add a roughly 3.58 MHz sine wave and use its phase to identify color. The amplitude of the sine wave gave the color’s brightness. The video explains why it is not exactly 3.58 MHz but 3.579545 MHz. This made it nearly invisible on older TVs, and new black-and-white sets incorporate a trap to filter that frequency out anyway. So you can identify any color by providing a phase angle and amplitude.

The final part of the puzzle is to filter the color signal, which makes it appear fuzzy, while retaining the sharp black-and-white image that your eye processes as a perfectly good image. If you can make the black-and-white signal line up with the color signal, you get a nice image. In older sets, this was done with a short delay line, although newer TVs used comb filters. Some TV systems, like PAL, relied on longer delays and had correspondingly beefier delay lines.

There are plenty of more details. Watch the video. We love how, back then, engineers worried about backward compatibility. Like stereo records, for example. Even though NTSC (sometimes jokingly called “never twice the same color”) has been dead for a while, we still like to look back at it.