God Mode On: how we attacked a vehicle’s head unit modem

Introduction

Imagine you’re cruising down the highway in your brand-new electric car. All of a sudden, the massive multimedia display fills with Doom, the iconic 3D shooter game. It completely replaces the navigation map or the controls menu, and you realize someone is playing it remotely right now. This is not a dream or an overactive imagination – we’ve demonstrated that it’s a perfectly realistic scenario in today’s world.

The internet of things now plays a significant role in the modern world. Not only are smartphones and laptops connected to the network, but also factories, cars, trains, and even airplanes. Most of the time, connectivity is provided via 3G/4G/5G mobile data networks using modems installed in these vehicles and devices. These modems are increasingly integrated into a System-on-Chip (SoC), which uses a Communication Processor (CP) and an Application Processor (AP) to perform multiple functions simultaneously. A general-purpose operating system such as Android can run on the AP, while the CP, which handles communication with the mobile network, typically runs on a dedicated OS. The interaction between the AP, CP, and RAM within the SoC at the microarchitecture level is a “black box” known only to the manufacturer – even though the security of the entire SoC depends on it.

Bypassing 3G/LTE security mechanisms is generally considered a purely academic challenge because a secure communication channel is established when a user device (User Equipment, UE) connects to a cellular base station (Evolved Node B, eNB). Even if someone can bypass its security mechanisms, discover a vulnerability in the modem, and execute their own code on it, this is unlikely to compromise the device’s business logic. This logic (for example, user applications, browser history, calls, and SMS on a smartphone) resides on the AP and is presumably not accessible from the modem.

To find out, if that is true, we conducted a security assessment of a modern SoC, Unisoc UIS7862A, which features an integrated 2G/3G/4G modem. This SoC can be found in various mobile devices by multiple vendors or, more interestingly, in the head units of modern Chinese vehicles, which are becoming increasingly common on the roads. The head unit is one of a car’s key components, and a breach of its information security poses a threat to road safety, as well as the confidentiality of user data.

During our research, we identified several critical vulnerabilities at various levels of the Unisoc UIS7862A modem’s cellular protocol stack. This article discusses a stack-based buffer overflow vulnerability in the 3G RLC protocol implementation (CVE-2024-39432). The vulnerability can be exploited to achieve remote code execution at the early stages of connection, before any protection mechanisms are activated.

Importantly, gaining the ability to execute code on the modem is only the entry point for a complete remote compromise of the entire SoC. Our subsequent efforts were focused on gaining access to the AP. We discovered several ways to do so, including leveraging a hardware vulnerability in the form of a hidden peripheral Direct Memory Access (DMA) device to perform lateral movement within the SoC. This enabled us to install our own patch into the running Android kernel and execute arbitrary code on the AP with the highest privileges. Details are provided in the relevant sections.

Acquiring the modem firmware

The modem at the center of our research was found on the circuit board of the head unit in a Chinese car.

Description of the circuit board components:

| Number in the board photo | Component |

| 1 | Realtek RTL8761ATV 802.11b/g/n 2.4G controller with wireless LAN (WLAN) and USB interfaces (USB 1.0/1.1/2.0 standards) |

| 2 | SPRD UMW2652 BGA WiFi chip |

| 3 | 55966 TYADZ 21086 chip |

| 4 | SPRD SR3595D (Unisoc) radio frequency transceiver |

| 5 | Techpoint TP9950 video decoder |

| 6 | UNISOC UIS7862A |

| 7 | BIWIN BWSRGX32H2A-48G-X internal storage, Package200-FBGA, ROM Type – Discrete, ROM Size – LPDDR4X, 48G |

| 8 | SCY E128CYNT2ABE00 EMMC 128G/JEDEC memory card |

| 9 | SPREADTRUM UMP510G5 power controller |

| 10 | FEI.1s LE330315 USB2.0 shunt chip |

| 11 | SCT2432STER synchronous step-down DC-DC converter with internal compensation |

Using information about the modem’s hardware, we desoldered and read the embedded multimedia memory card, which contained a complete image of its operating system. We then analyzed the image obtained.

Remote access to the modem (CVE-2024-39431)

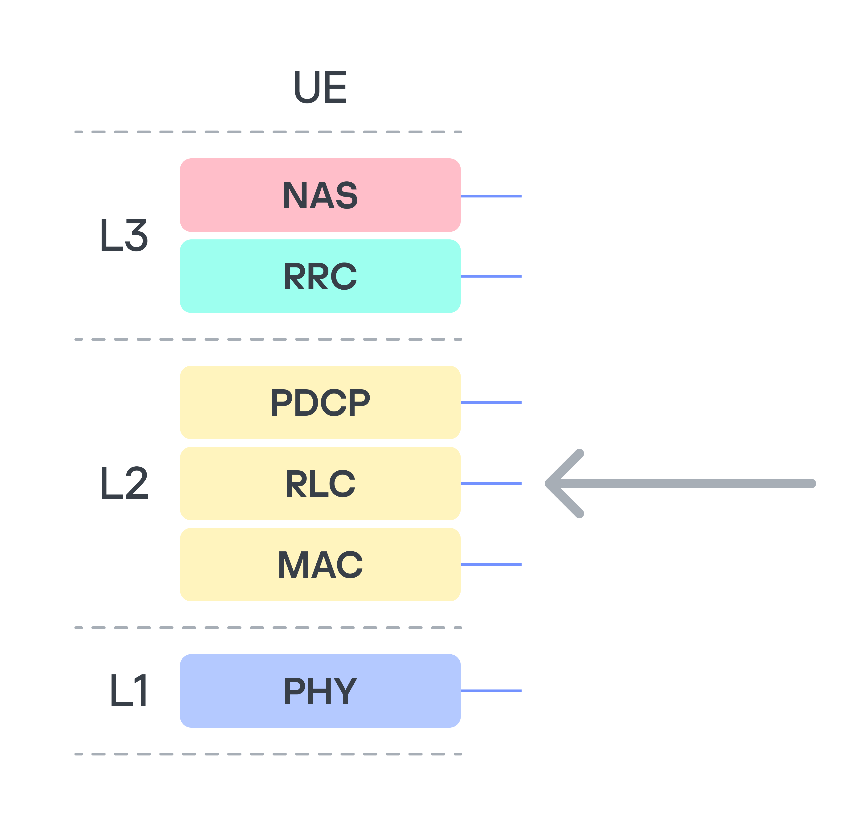

The modem under investigation, like any modern modem, implements several protocol stacks: 2G, 3G, and LTE. Clearly, the more protocols a device supports, the more potential entry points (attack vectors) it has. Moreover, the lower in the OSI network model stack a vulnerability sits, the more severe the consequences of its exploitation can be. Therefore, we decided to analyze the data packet fragmentation mechanisms at the data link layer (RLC protocol).

We focused on this protocol because it is used to establish a secure encrypted data transmission channel between the base station and the modem, and, in particular, it is used to transmit higher-layer NAS (Non-Access Stratum) protocol data. NAS represents the functional level of the 3G/UMTS protocol stack. Located between the user equipment (UE) and core network, it is responsible for signaling between them. This means that a remote code execution (RCE) vulnerability in RLC would allow an attacker to execute their own code on the modem, bypassing all existing 3G communication protection mechanisms.

The RLC protocol uses three different transmission modes: Transparent Mode (TM), Unacknowledged Mode (UM), and Acknowledged Mode (AM). We are only interested in UM, because in this mode the 3G standard allows both the segmentation of data and the concatenation of several small higher-layer data fragments (Protocol Data Units, PDU) into a single data link layer frame. This is done to maximize channel utilization. At the RLC level, packets are referred to as Service Data Units (SDU).

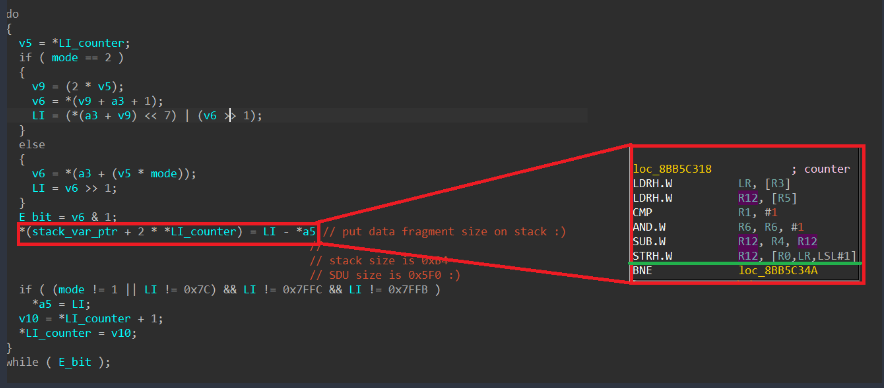

Among the approximately 75,000 different functions in the firmware, we found the function for handling an incoming SDU packet. When handling a received SDU packet, its header fields are parsed. The packet itself consists of a mandatory header, optional headers, and data. The number of optional headers is not limited. The end of the optional headers is indicated by the least significant bit (E bit) being equal to 0. The algorithm processes each header field sequentially, while their E-bits equal 1. During processing, data is written to a variable located on the stack of the calling function. The stack depth is 0xB4 bytes. The size of the packet that can be parsed (i.e., the number of headers, each header being a 2-byte entry on the stack) is limited by the SDU packet size of 0x5F0 bytes.

As a result, exploitation can be achieved using just one packet in which the number of headers exceeds the stack depth (90 headers). It is important to note that this particular function lacks a stack canary, and when the stack overflows, it is possible to overwrite the return address and some non-volatile register values in this function. However, overwriting is only possible with a value ending in one in binary (i.e., a value in which the least significant bit equals 1). Notably, execution takes place on ARM in Thumb mode, so all return addresses must have the least significant bit equal to 1. Coincidence? Perhaps.

In any case, sending the very first dummy SDU packet with the appropriate number of “correct” headers caused the device to reboot. However, at that moment, we had no way to obtain information on where and why the crash occurred (although we suspect the cause was an attempt to transfer control to the address 0xAABBCCDD, taken from our packet).

Gaining persistence in the system

The first and most important observation is that we know the pointer to the newly received SDU packet is stored in register R2. Return Oriented Programming (ROP) techniques can be used to execute our own code, but first we need to make sure it is actually possible.

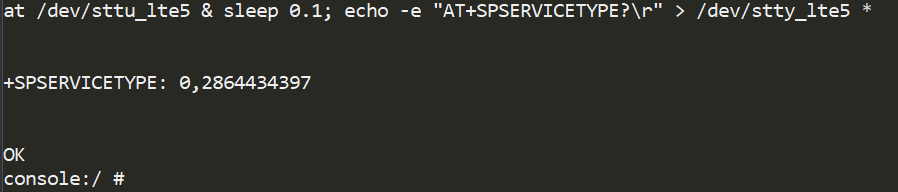

We utilized the available AT command handler to move the data to RAM areas. Among the available AT commands, we found a suitable function – SPSERVICETYPE.

Next, we used ROP gadgets to overwrite the address 0x8CE56218 without disrupting the subsequent operation of the incoming SDU packet handling algorithm. To achieve this, it was sufficient to return to the function from which the SDU packet handler was called, because it was invoked as a callback, meaning there is no data linkage on the stack. Given that this function only added 0x2C bytes to the stack, we needed to fit within this size.

Having found a suitable ROP chain, we launched an SDU packet containing it as a payload. As a result, we saw the output 0xAABBCCDD in the AT command console for SPSERVICETYPE. Our code worked!

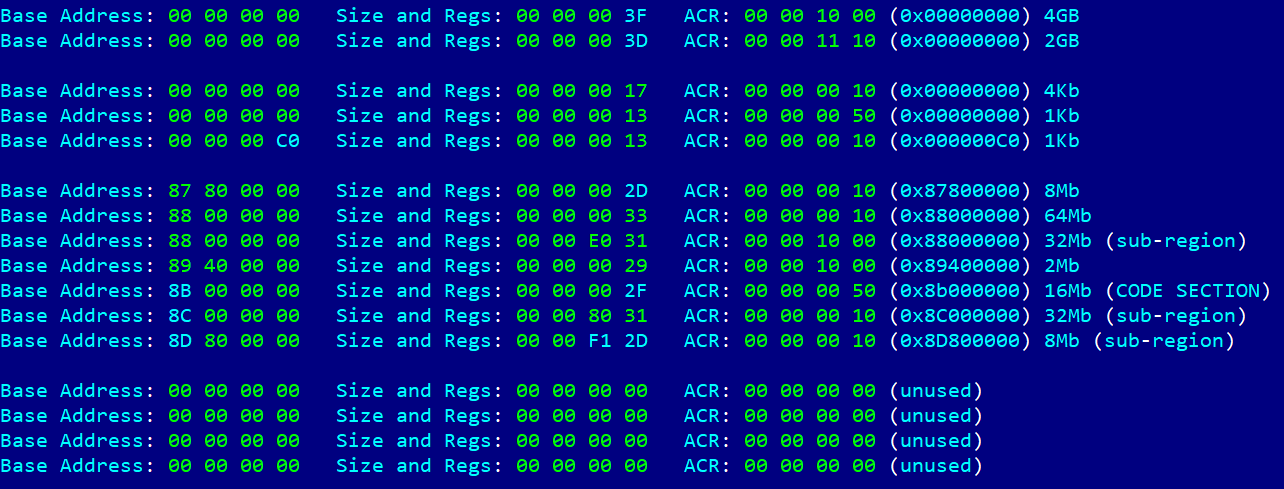

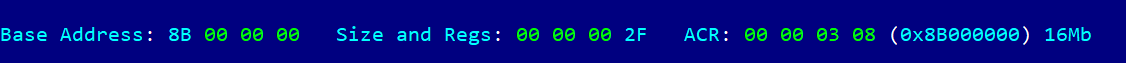

Next, by analogy, we input the address of the stack frame where our data was located, but it turned out not to be executable. We then faced the task of figuring out the MPU settings on the modem. Once again, using the ROP chain method, we generated code that read the MPU table, one DWORD at a time. After many iterations, we obtained the following table.

The table shows what we suspected – the code section is only mapped for execution. An attempt to change the configuration resulted in another ROP chain, but this same section was now mapped with write permissions in an unused slot in the table. Because of MPU programming features, specifically the presence of the overlap mechanism and the fact that a region with a higher ID has higher priority, we were able to write to this section.

All that remained was to use the pointer to our data (still stored in R2) and patch the code section that had just been unlocked for writing. The question was what exactly to patch. The simplest method was to patch the NAS protocol handler by adding our code to it. To do this, we used one of the NAS protocol commands – MM information. This allowed us to send a large amount of data at once and, in response, receive a single byte of data using the MM status command, which confirmed the patching success.

As a result, we not only successfully executed our own code on the modem side but also established full two-way communication with the modem, using the high-level NAS protocol as a means of message delivery. In this case, it was an MM Status packet with the cause field equaling 0xAA.

However, being able to execute our own code on the modem does not give us access to user data. Or does it?

The full version of the article with a detailed description of the development of an AR exploit that led to Doom being run on the head unit is available on ICS CERT website.