Digital Forensics: Volatility – Memory Analysis Guide, Part 2

Hello, aspiring digital forensics investigators!

Welcome back to our guide on memory analysis!

In the first part, we covered the fundamentals, including processes, dumps, DLLs, handles, and services, using Volatility as our primary tool. We created this series to give you more clarity and help you build confidence in handling memory analysis cases. Digital forensics is a fascinating area of cybersecurity and earning a certification in it can open many doors for you. Once you grasp the key concepts, you’ll find it easier to navigate the field. Ultimately, it all comes down to mastering a core set of commands, along with persistence and curiosity. Governments, companies, law enforcement and federal agencies are all in need of skilled professionals As cyberattacks become more frequent and sophisticated, often with the help of AI, opportunities for digital forensics analysts will only continue to grow.

Now, in part two, we’re building on that to explore more areas that help uncover hidden threats. We’ll look at network info to see connections, registry keys for system changes, files in memory, and some scans like malfind and Yara rules to find malware. Plus, as promised, there are bonuses at the end for quick ways to pull out extra details

Network Information

As a beginner analyst, you’d run network commands to check for sneaky connections, like if malware is phoning home to hackers. For example, imagine investigating a company’s network after a data breach, these tools could reveal a hidden link to a foreign server stealing customer info, helping you trace the attacker.

‘Netscan‘ scans for all network artifacts, including TCP/UDP. ‘Netstat‘ lists active connections and sockets. In Vol 2, XP/2003-specific ones like ‘connscan‘ and ‘connections‘ focus on TCP, ‘sockscan‘ and ‘sockets‘ on sockets, but they’re old and not present in Vol 3.

Volatility 2:

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” ‑‑profile <profile> netscan

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” ‑‑profile <profile> netstat

XP/2003 SPECIFIC:

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” ‑‑profile <profile> connscan

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” ‑‑profile <profile> connections

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” ‑‑profile <profile> sockscan

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” ‑‑profile <profile> sockets

Volatility 3:

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” windows.netscan

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” windows.netstat

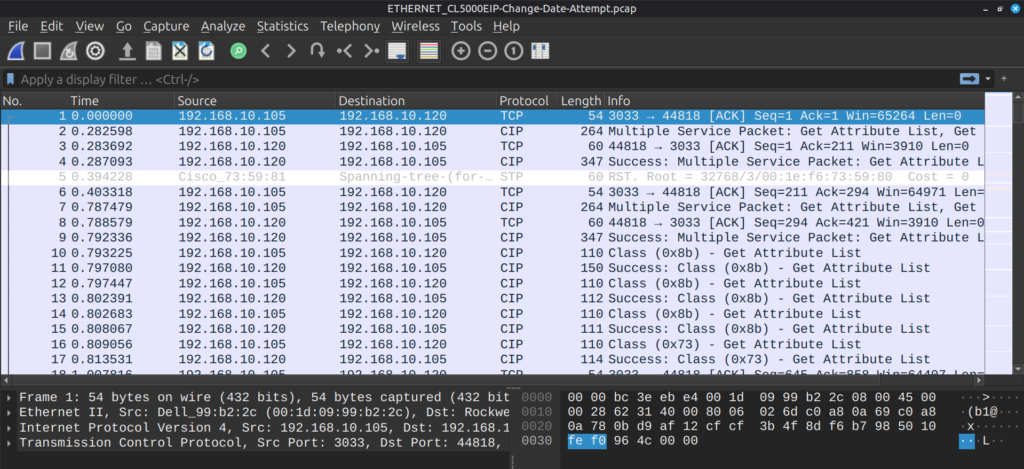

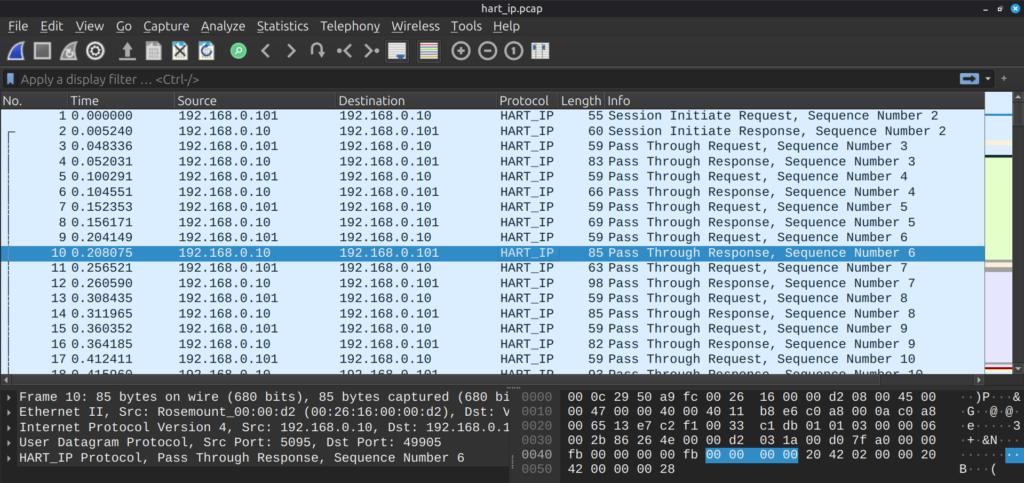

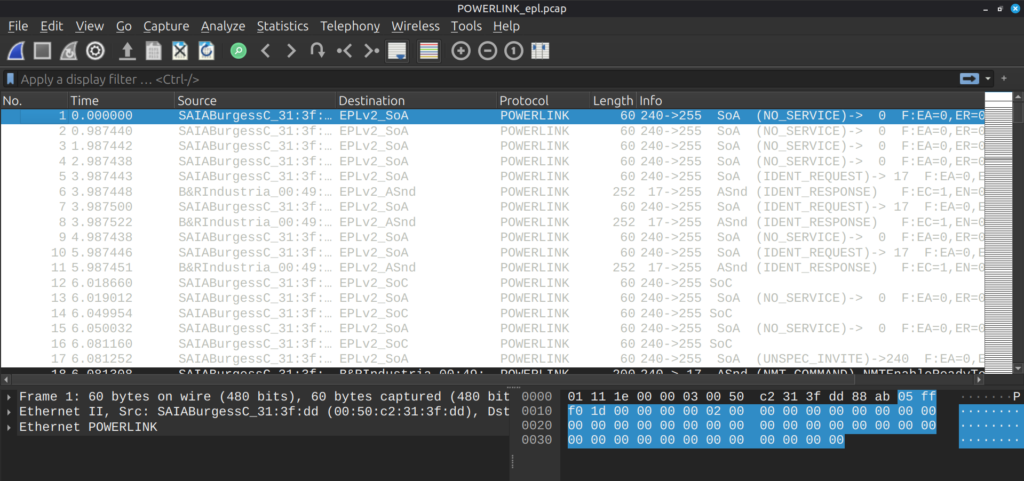

bash$ > vol -f Windows7.vmem windows.netscan

This output shows network connections with protocols, addresses, and PIDs. Perfect for spotting unusual traffic.

bash$ > vol -f Windows7.vmem windows.netstat

Here, you’ll get a list of active sockets and states, like listening or established links.

Note, the XP/2003 specific plugins are deprecated and therefore not available in Volatility 3, although are still common in the poorly financed government sector.

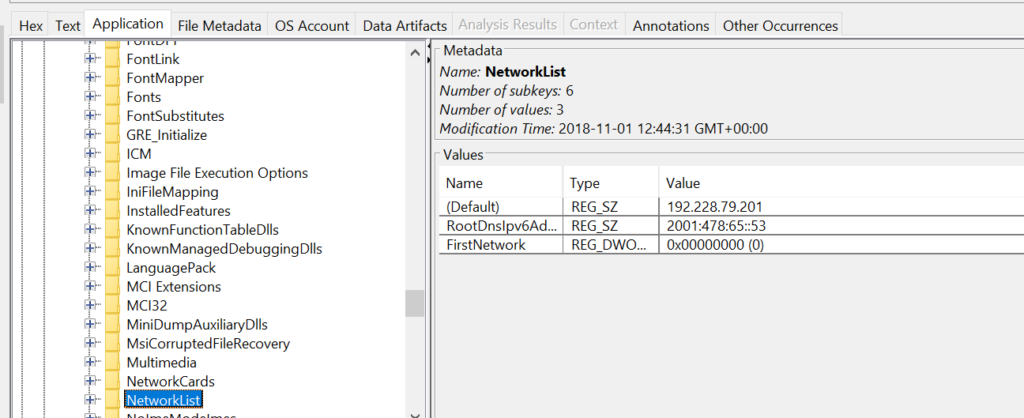

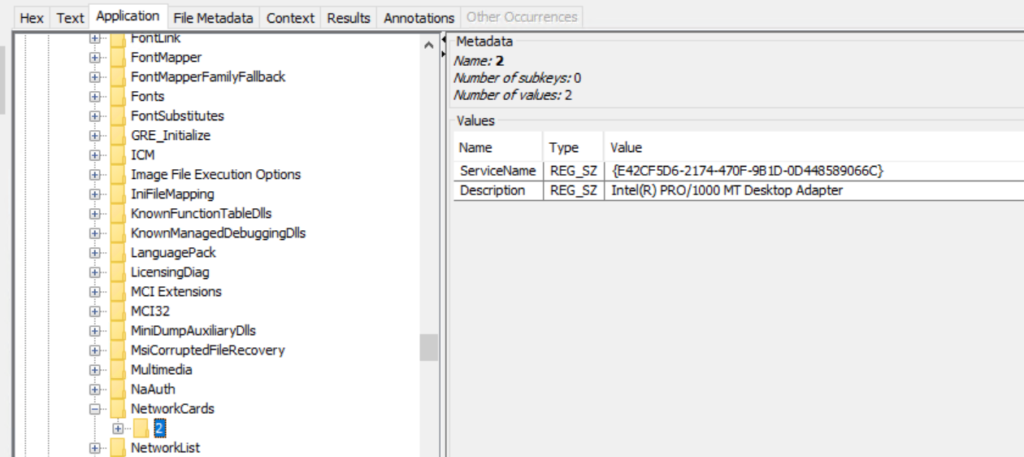

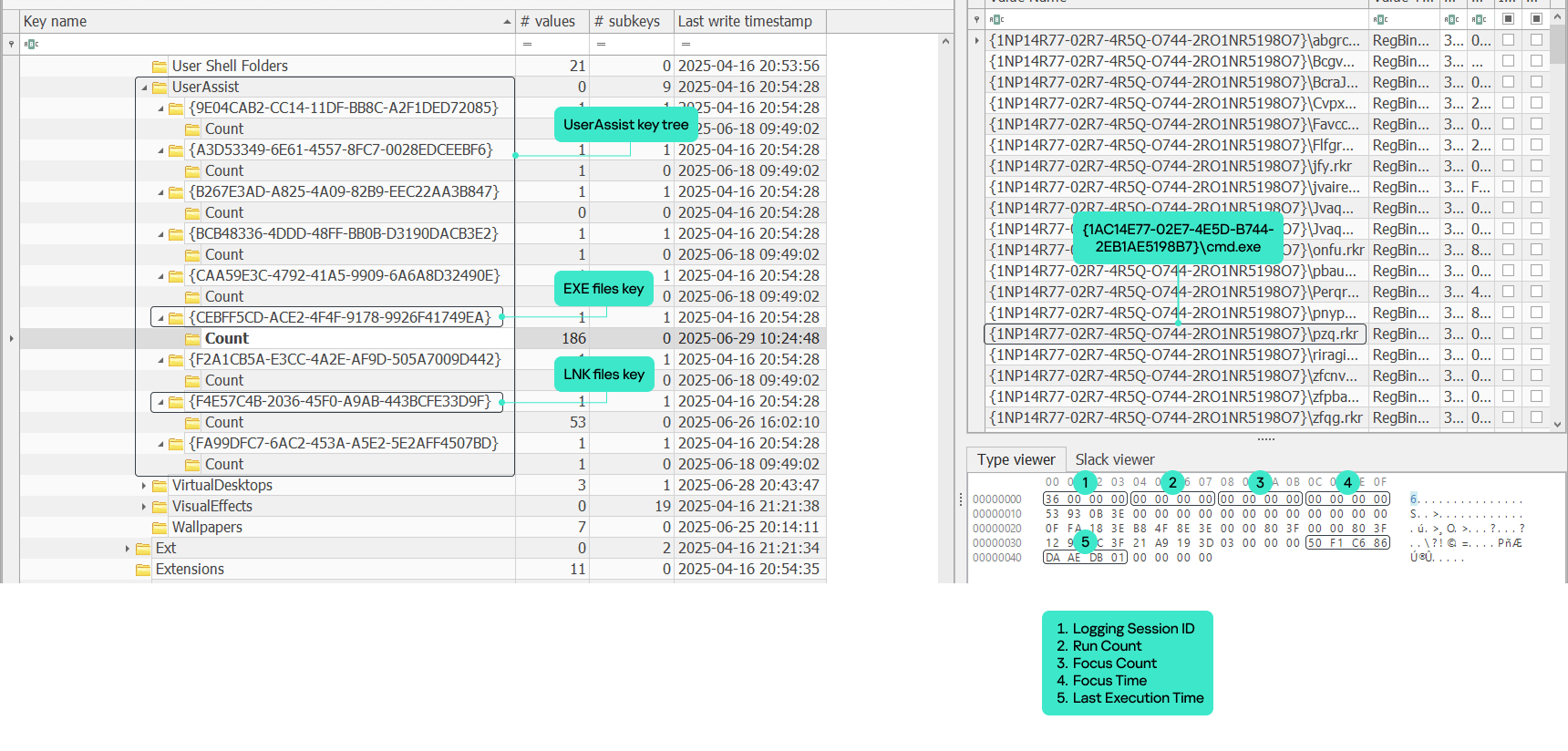

Registry

Hive List

You’d use hive list commands to find registry hives in memory, which store system settings malware often tweaks these for persistence. Say you’re checking a home computer after suspicious pop-ups. This could show changes to startup keys that launch bad software every boot.

‘hivescan‘ scans for hive structures. ‘hivelist‘ lists them with virtual and physical addresses.

Volatility 2:

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” ‑‑profile <profile> hivescan

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” ‑‑profile <profile> hivelist

Volatility 3:

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” windows.registry.hivescan

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” windows.registry.hivelist

bash$ > vol -f Windows7.vmem windows.registry.hivelist

This lists the registry hives with their paths and offsets for further digging.

bash$ > vol -f Windows7.vmem windows.registry.hivescan

The scan output highlights hive locations in memory.

Printkey

Printkey is handy for viewing specific registry keys and values, like checking for malware-added entries. For instance, in a ransomware case, you might look at keys that control file associations to see if they’ve been hijacked.

Without a key, it shows defaults, while -K or –key targets a certain path.

Volatility 2:

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” ‑‑profile <profile> printkey

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” ‑‑profile <profile> printkey -K “Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion”

Volatility 3:

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” windows.registry.printkey

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” windows.registry.printkey ‑‑key “Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion”

bash$ > vol -f Windows7.vmem windows.registry.printkey

This gives a broad view of registry keys.

bash$ > vol -f Windows7.vmem windows.registry.printkey –key “Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion”

Here, it focuses on the specified key, showing subkeys and values.

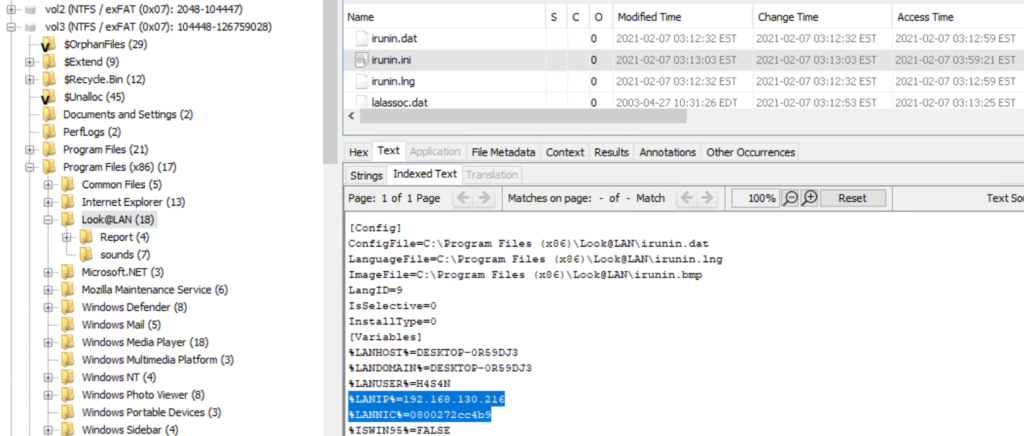

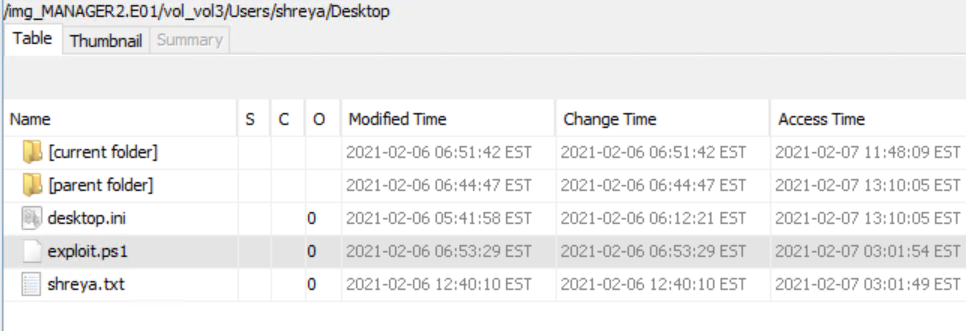

Files

File Scan

Filescan helps list files cached in memory, even deleted ones, great for finding malware files that were run but erased from disk. This can uncover temporary files from the infection.

Both versions scan for file objects in memory pools.

Volatility 2:

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” ‑‑profile <profile> filescan

Volatility 3:

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” windows.filescan

bash$ > vol -f Windows7.vmem windows.filescan

This output lists file paths, offsets, and access types.

File Dump

You’d dump files to extract them from memory for closer checks, like pulling a suspicious script. In a corporate espionage probe, dumping a hidden document could reveal leaked secrets.

Without options, it dumps all. With offsets or PID, it targets specific ones. Vol 3 uses virtual or physical addresses.

Volatility 2:

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” ‑‑profile <profile> dumpfiles ‑‑dump-dir=“/path/to/dir”

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” ‑‑profile <profile> dumpfiles ‑‑dump-dir=“/path/to/dir” -Q <offset>

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” ‑‑profile <profile> dumpfiles ‑‑dump-dir=“/path/to/dir” -p <PID>

Volatility 3:

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” -o “/path/to/dir” windows.dumpfiles

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” -o “/path/to/dir” windows.dumpfiles ‑‑virtaddr <offset>

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” -o “/path/to/dir” windows.dumpfiles ‑‑physaddr <offset>

bash$ > vol -f Windows7.vmem windows.dumpfiles

This pulls all cached files Windows has in RAM.

Miscellaneous

Malfind

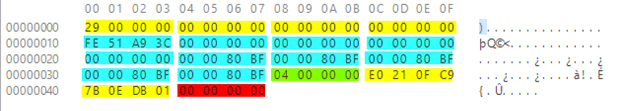

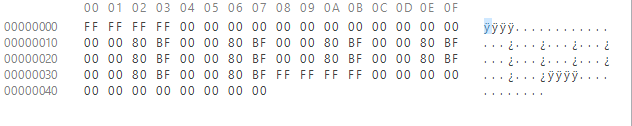

Malfind scans for injected code in processes, flagging potential malware.

Vol 2 shows basics like hexdump. Vol 3 adds more details like protection and disassembly.

Volatility 2:

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” ‑‑profile <profile> malfind

Volatility 3:

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” windows.malfind

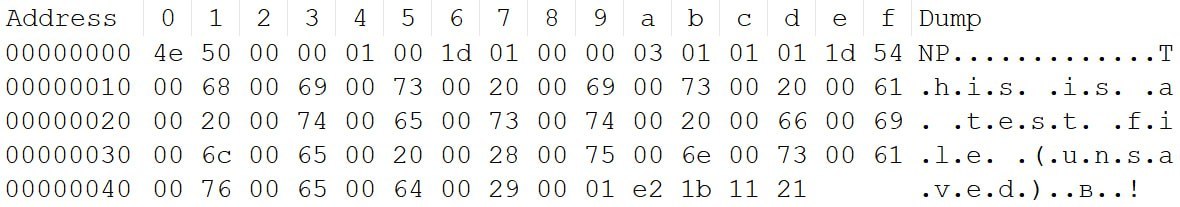

bash$ > vol -f Windows7.vmem windows.malfind

This highlights suspicious memory regions with details.

Yara Scan

Yara scan uses rules to hunt for malware patterns across memory. It’s like a custom detector. For example, during a widespread attack like WannaCry, a Yara rule could quickly find infected processes.

Vol 2 uses file path. Vol 3 allows inline rules, file, or kernel-wide scan.

Volatility 2:

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” yarascan -y “/path/to/file.yar”

Volatility 3:

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” windows.vadyarascan ‑‑yara-rules <string>

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” windows.vadyarascan ‑‑yara-file “/path/to/file.yar”

vol.py -f “/path/to/file” yarascan.yarascan ‑‑yara-file “/path/to/file.yar”

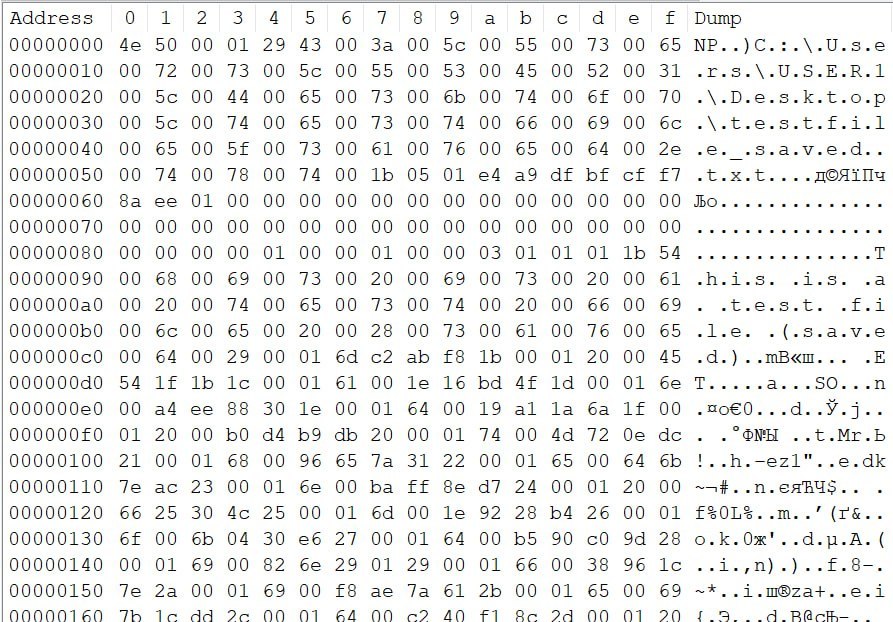

bash$ > vol -f Windows7.vmem windows.vadyarascan –yara-file yara_fules/Wannacrypt.yar

As you can see we found the malware and all related processes to it with the help of the rule

Bonus

Using the strings command, you can quickly uncover additional useful details, such as IP addresses, email addresses, and remnants from PowerShell or command prompt activities.

Emails

bash$ > strings Windows7.vmem | grep -oE "\b[A-Za-z0-9._%+-]+@[A-Za-z0-9.-]+\.[A-Za-z]{2,4}\b"

IPs

bash$ > strings Windows7.vmem | grep -oE "\b[A-Za-z0-9._%+-]+@[A-Za-z0-9.-]+\.[A-Za-z]{2,4}\b"

Powershell and CMD artifacts

bash$ > strings Windows7.vmem | grep -E "(cmd|powershell|bash)[^\s]+"

Summary

By now you should feel comfortable with all the network analysis, file dumps, hives and registries we had to go through. As you practice, your confidence will grow fast. The commands covered here will help you solve most of the cases as they are fundamental. Also, don’t forget that Volatility has a lot more different plugins that you may want to explore. Feel free to come back to this guide anytime you want. Part 1 will remind you how to approach a memory dump, while Part 2 has the commands you need. In this part, we’ve expanded your Volatility toolkit with network scans to track connections, registry tools to check settings, file commands to extract cached items, and miscellaneous scans like malfind for injections and Yara for pattern matching. Together they give you a solid set of steps.

If you want to turn this into a career, our digital forensics courses are built to get you there. Many students use this training to prepare for industry certifications and job interviews. Our focus is on the practical skills that hiring teams look for.