Dissecting and Exploiting TCP/IP RCE Vulnerability “EvilESP”

September’s Patch Tuesday unveiled a critical remote vulnerability in tcpip.sys, CVE-2022-34718. The advisory from Microsoft reads: “An unauthenticated attacker could send a specially crafted IPv6 packet to a Windows node where IPsec is enabled, which could enable a remote code execution exploitation on that machine.”

Pure remote vulnerabilities usually yield a lot of interest, but even over a month after the patch, no additional information outside of Microsoft’s advisory had been publicly published. From my side, it had been a long time since I attempted to do a binary patch diff analysis, so I thought this would be a good bug to do root cause analysis and craft a proof-of-concept (PoC) for a blog post.

On October 21 of last year, I posted an exploit demo and root cause analysis of the bug. Shortly thereafter a blog post and PoC was published by Numen Cyber Labs on the vulnerability, using a different exploitation method than I used in my demo.

In this blog — my follow-up article to my exploit video — I include an in-depth explanation of the reverse engineering of the bug and correct some inaccuracies I found in the Numen Cyber Labs blog.

In the following sections, I cover reverse engineering the patch for CVE-2022-34718, the affected protocols, identifying the bug, and reproducing it. I’ll outline setting up a test environment and write an exploit to trigger the bug and cause a Denial of Service (DoS). Finally, I’ll look at exploit primitives and outline the next steps to turn the primitives into remote code execution (RCE).

Patch Diffing

Microsoft’s advisory does not contain any specific details of the vulnerability except that it is contained in the TCP/IP driver and requires IPsec to be enabled. In order to identify the specific cause of the vulnerability, we’ll compare the patched binary to the pre-patch binary and try to extract the “diff”(erence) using a tool called BinDiff.

I used Winbindex to obtain two versions of tcpip.sys: one right before the patch and one right after, both for the same version of Windows. Getting sequential versions of the binaries is important, as even using versions a few updates apart can introduce noise from differences that are not related to the patch, and cause you to waste time while doing your analysis. Winbindex has made patch analysis easier than ever, as you can obtain any Windows binary beginning from Windows 10. I loaded both of the files in Ghidra, applied the Program Database (pdb) files, and ran auto analysis (checking aggressive instruction finder works best). Afterward, the files can be exported into a BinExport format using the extension BinExport for Ghidra. The files can then be loaded into BinDiff to create a diff and start analyzing their differences:

BinDiff summary comparing the pre- and post-patch binaries

BinDiff works by matching functions in the binaries being compared using various algorithms. In this case there, we have applied function symbol information from Microsoft, so all the functions can be matched by name.

List of matched functions sorted by similarity

Above we see there are only two functions that have a similarity less than 100%. The two functions that were changed by the patch are IppReceiveEsp and Ipv6pReassembleDatagram.

Vulnerability Root Cause Analysis

Previous research shows the Ipv6pReassembleDatagram function handles reassembling Ipv6 fragmented packets.

The function name IppReceiveEsp seems to indicate this function handles the receiving of IPsec ESP packets.

Before diving into the patch, I’ll briefly cover Ipv6 fragmentation and IPsec. Having a general understanding of these packet structures will help when attempting to reverse engineer the patch.

IPv6 Fragmentation:

An IPv6 packet can be divided into fragments with each fragment sent as a separate packet. Once all of the fragments reach the destination, the receiver reassembles them to form the original packet.

The diagram below illustrates the fragmentation:

Illustration of Ipv6 fragmentation

According to the RFC, fragmentation is implemented via an Extension Header called the Fragment header, which has the following format:

Ipv6 Fragment Header format

Where the Next Header field is the type of header present in the fragmented data.

IPsec (ESP):

IPsec is a group of protocols that are used together to set up encrypted connections. It’s often used to set up Virtual Private Networks (VPNs). From the first part of patch analysis, we know the bug is related to the processing of ESP packets, so we’ll focus on the Encapsulating Security Payload (ESP) protocol.

As the name suggests, the ESP protocol encrypts (encapsulates) the contents of a packet. There are two modes: in tunnel mode, a copy of IP header is contained in the encrypted payload, and in transport mode where only the transport layer portion of the packet is encrypted. Like IPv6 fragmentation, ESP is implemented as an extension header. According to the RFC, an ESP packet is formatted as follows:

Top Level Format of an ESP Packet

Where Security Parameters Index (SPI) and Sequence Number fields comprise the ESP extension header, and the fields between and including Payload Data and Next Header are encrypted. The Next Header field describes the header contained in Payload Data.

Now with a primer of Ipv6 Fragmentation and IPsec ESP, we can continue the patch diff analysis by analyzing the two functions we found were patched.

Ipv6pReassembleDatagram

Comparing the side by side of the function graphs, we can see that a single new code block has been introduced into the patched function:

Side-by-side comparison of the pre- and post-patch function graphs of Ipv6ReassembleDatagram

Let’s take a closer look at the block:

New code block in the patched function

The new code block is doing a comparison of two unsigned integers (in registers EAX and EDX) and jumping to a block if one value is less than the other. Let’s take a look at that destination block:

The target code has an unconditional call to the function IppDeleteFromReassemblySet. Taking a guess from the name of this function, this block seems to be for error handling. We can intuit that the new code that was added is some sort of bounds check, and there has been a “goto error” line inserted into the code, if the check fails.

With this bit of insight, we can perform static analysis in a decompiler.

0vercl0ck previously published a blog post doing vulnerability analysis on a different Ipv6 vulnerability and went deep into the reverse engineering of tcpip.sys. From this work and some additional reverse engineering, I was able to fill in structure definitions for the undocumented Packet_t and Reassembly_t objects, as well as identify a couple of crucial local variable assignments.

Decompilation output of Ipv6ReassembleDatagram

In the above code snippet, the pink box surrounds the new code added by the patch. Reassembly->nextheader_offset contains the byte offset of the next_header field in the Ipv6 fragmentation header. The bounds check compares next_header_offset to the length of the header buffer. On line 29, HeaderBufferLen is used to allocate a buffer and on line 35, Reassembly->nextheder_offset is used to index and copy into the allocated buffer.

Because this check was added, we now know there was a condition that allows nextheader_offset to exceed the header buffer length. We’ll move on to the second patched function to seek more answers.

IppReceiveEsp

Looking at the function graph side by side in the BinDiff workspace, we can identify some new code blocks introduced into the patched function:

Side-by-side comparison of the pre- and post-patch function graphs of IppReceiveEsp

The image below shows the decompilation of the function IppReceiveEsp, with a pink box surrounding the new code added by the patch.

Decompilation output of IppReceiveESP

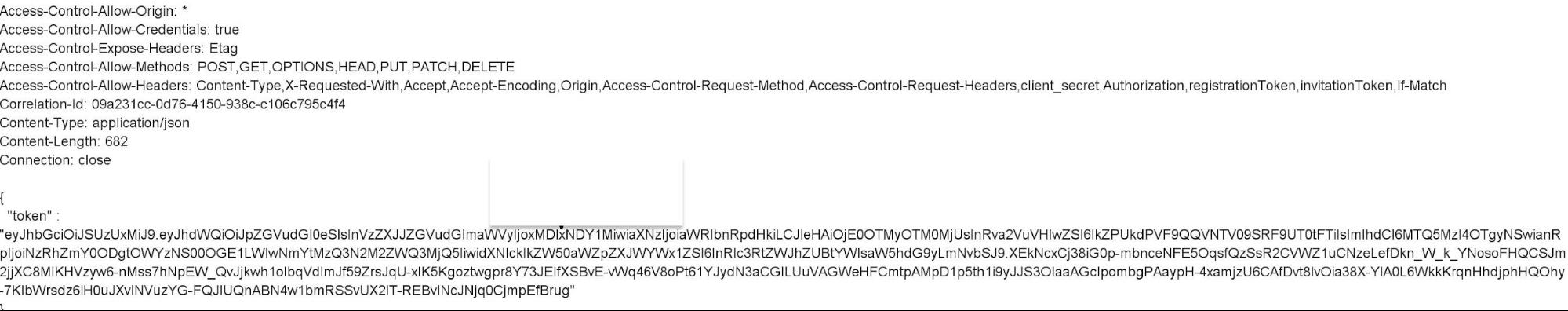

Here, a new check was added to examine the Next Header field of the ESP packet. The Next Header field identifies the header of the decrypted ESP packet. Recall that a Next Header value can correspond to an upper layer protocol (such as TCP or UDP) or an extension header (such as fragmentation header or routing header). If the value in NextHeader is 0, 0x2B, or 0x2C, IppDiscardReceivedPackets is called and the error code is set to STATUS_DATA_NOT_ACCEPTED. These values correspond to IPv6 Hop-by-Hop Option, Routing Header for Ipv6, and Fragment Header for IPv6, respectively.

Referring back to the ESP RFC it states, “In the IPv6 context, ESP is viewed as an end-to-end payload, and thus should appear after hop-by-hop, routing, and fragmentation extension headers.” Now the problem becomes clear. If a header of these types is contained within an ESP payload, it violates the RFC of the protocol, and the packet will be discarded.

Putting It All Together

Now that we have diagnosed the patches in two different functions, we can figure out how they are related. In the first function Ipv6ReassembleDatagram, we determined the fix was for a buffer overflow.

Decompilation output of Ipv6ReassembleDatagram

Recall that the size of the victim buffer is calculated as the size of the extension headers, plus the size of an Ipv6 header (Line 10 above). Now refer back to the patch that was inserted (Line 16). Reassembly->nextheader_offset refers to the offset of the Next Header value of the buffer holding the data for the fragment.

Now refer back to the structure of an ESP packet:

Top Level Format of an ESP Packet

Notice that the Next Header field comes *after* Payload Data. This means that Reassembly->nextheader_offset will include the size of the Payload Data, which is controlled by the size of the data, and can be much greater than the size of the extension headers. The expected location of the Next Header field is inside an extension header or Ipv6 header. In an ESP packet, it is not inside the header, since it is actually contained in the encrypted portion of the packet.

Illustrated root cause of CVE-2022-34718

Now refer back to line 35 of Ipv6ReassembleDatagram, this is where an out of bounds 1 byte write occurs (the size and value of NextHeader).

Reproducing the Bug

We now know the bug can be triggered by sending an IPv6 fragmented datagram via IPsec ESP packets.

The next question to answer: how will the victim be able to decrypt the ESP packets?

To answer this question, I first tried to send packets to a victim containing an ESP Header with junk data and put a breakpoint on to the vulnerable IppReceiveEsp function, to see if the function could be reached. The breakpoint was hit, but the internal function I thought did the decrypting IppReceiveEspNbl, returned an error, so the vulnerable code was never reached. I further reverse engineered IppReceiveEspNbl and worked my way through to find the point of failure. This is where I learned that in order to successfully decrypt an ESP packet, a security association must be established.

A security association consists of a shared state, primarily cryptographic keys and parameters, maintained between two endpoints to secure traffic between them. In simple terms, a security association defines how a host will encrypt/decrypt/authenticate traffic coming from/going to another host. Security associations can be established via the Internet Key Exchange (IKE) or Authenticated IP Protocol. In essence, we need a way to establish a security association with the victim, so that it knows how to decrypt the incoming data from the attacker.

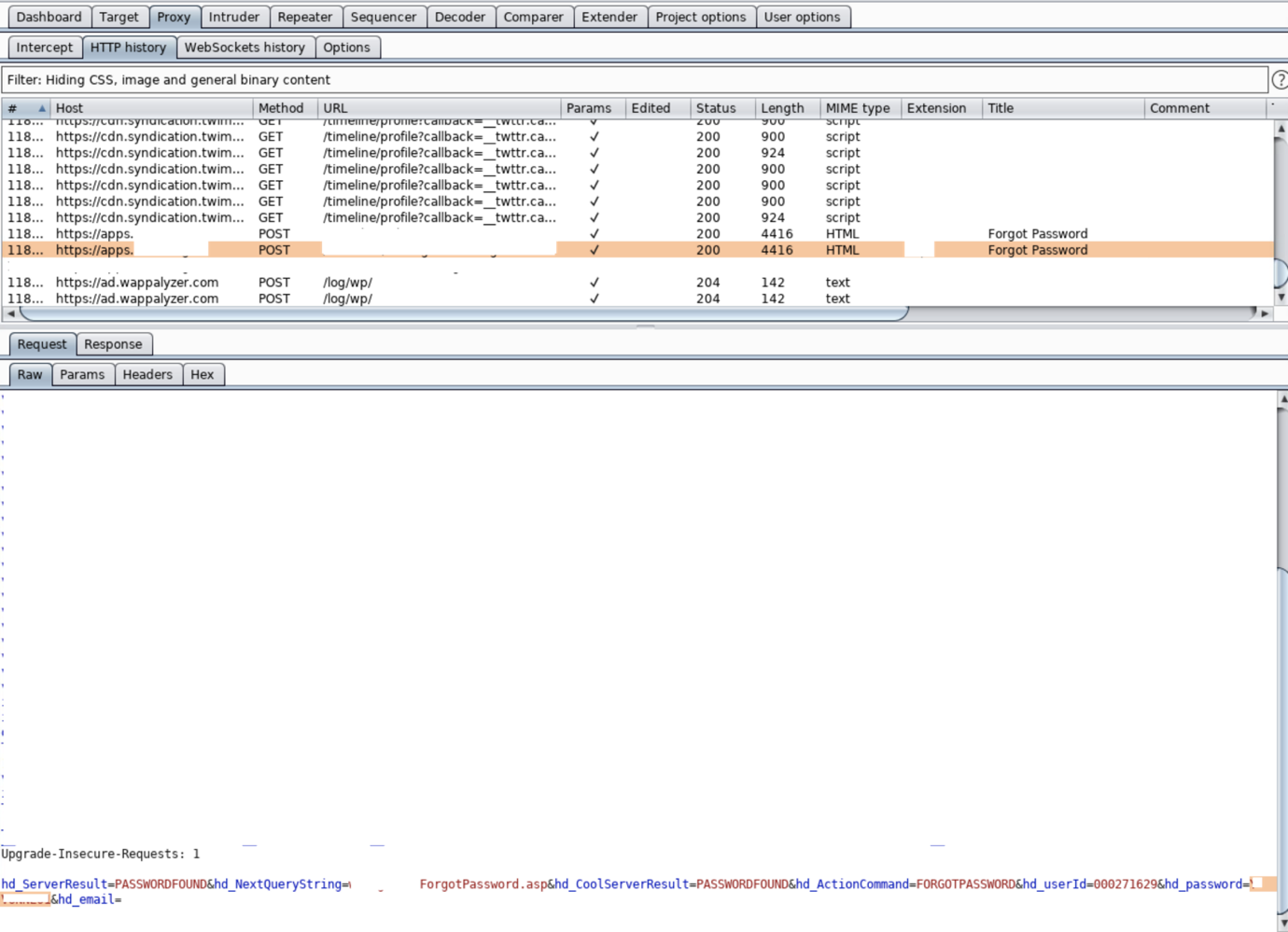

For testing purposes, instead of implementing IKE, I decided to create a security association on the victim manually. This can be done using the Windows Filtering Platform WinAPI (WFP). Numen’s blog post stated that it’s not possible to use WFP for secret key management. However, that is incorrect and by modifying sample code provided by Microsoft, it’s possible to set a symmetric key that the victim will use to decrypt ESP packets coming from the attacker IP.

Exploitation

Now that the victim knows how to decrypt ESP traffic from us (the attacker) we can build malformed encrypted ESP packets using scapy. Using scapy we can send packets at the IP layer. The exploitation process is simple:

CVE-2022-34718 PoC

I create a set of fragmented packets from an ICMPv6 Echo request. Then for each fragment, they are encrypted into an ESP layer before sending.

Primitive

From the root cause analysis diagram pictured above, we know our primitive gives us an out of bounds write at

offset = sizeof(Payload Data) + sizeof(Padding) + sizeof(Padding Length)

The value of the write is controllable via the value of the Next Header field. I set this value on line 36 in my exploit above (0x41 😉).

Denial of Service (DoS)

Corrupting just one byte into a random offset of the NetIoProtocolHeader2 pool (where the target buffer is allocated), usually does not immediately cause a crash. We can reliably crash the target by inserting additional headers within the fragmented message to parse, or by repeatedly pinging the target after corrupting a large portion of the pool.

Limitations to Overcome For RCE

offset is attacker controlled, however according to the ESP RFC, padding is required such that the Integrity Check Value (ICV) field (if present) is aligned on a 4-byte boundary.

Because

sizeof(Padding Length) = sizeof(Next Header) = 1,

sizeof(Payload Data) + sizeof(Padding) + 2 must be 4 byte aligned.

And therefore:

offset = 4n - 1

Where n can be any positive integer, constrained by the fact the payload data and padding must fit within a single packet and is therefore limited by MTU (frame size). This is problematic because it means full pointers cannot be overwritten. This is limiting, but not necessarily prohibitive; we can still overwrite the offset of an address in an object, a size, a reference counter, etc. The possibilities available to us depend on what objects can be sprayed in the kernel pool where the victim headerBuff is allocated.

Heap Grooming Research

The affected kernel pool in WinDbg

The victim out of bounds buffer is allocated in the NetIoProtocolHeader2 pool. The first steps in heap grooming research are: examine the type of objects allocated in this pool, what is contained in them, how they are used, and how the objects are allocated/freed. This will allow us to examine how the write primitive can be used to obtain a leak or build a stronger primitive. We are not necessarily restricted to NetIoProtocolHeader2. However, because the position of the victim out-of-bounds buffer cannot be predicted, and the address of surrounding pools is randomized, targeting other pools seems challenging.

Demo

Watch the demo exploiting CVE-2022-34718 ‘EvilESP’ for DoS below:

Takeaways

When laid out like this, the bug seems pretty simple. However, it took several long days of reverse engineering and learning about various networking stacks and protocols to understand the full picture and write a DoS exploit. Many researchers will say that configuring the setup and understanding the environment is the most time-consuming and tedious part of the process, and this was no exception. I am very glad that I decided to do this short project; I understand Ipv6, IPsec, and fragmentation much better now.

To learn how IBM Security X-Force can help you with offensive security services, schedule a no-cost consult meeting here: IBM X-Force Scheduler.

If you are experiencing cybersecurity issues or an incident, contact X-Force to help: U.S. hotline 1-888-241-9812 | Global hotline (+001) 312-212-8034.

References

- https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc8200#section-4.5

- https://blog.quarkslab.com/analysis-of-a-windows-ipv6-fragmentation-vulnerability-cve-2021-24086.html

- https://doar-e.github.io/blog/2021/04/15/reverse-engineering-tcpipsys-mechanics-of-a-packet-of-the-death-cve-2021-24086/#diffing-microsoft-patches-in-2021

- https://www.iana.org/assignments/protocol-numbers/protocol-numbers.xhtml

- https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc4303

- https://msrc.microsoft.com/update-guide/en-US/vulnerability/CVE-2022-34718

The post Dissecting and Exploiting TCP/IP RCE Vulnerability “EvilESP” appeared first on Security Intelligence.