So Long Firefox, Hello Vivaldi

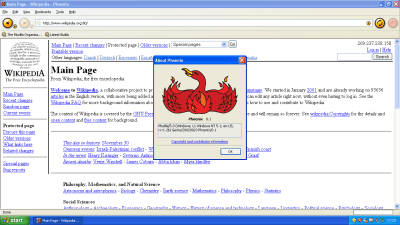

It’s been twenty-three years since the day Phoenix was released, the web browser that eventually became Firefox. I downloaded it on the first day and installed it on my trusty HP Omnibook 800 laptop, and until this year I’ve used it ever since. Yet after all this time, I’m ready to abandon it for another browser. In the previous article in this series I went into my concerns over the direction being taken by Mozilla with respect to their inclusion of AI features and my worries about privacy in Firefox, and I explained why a plurality of browser engines is important for the Web. Now it’s time to follow me on my search for a replacement, and you may be surprised by one aspect of my eventual choice.

Where Do I Go From Here?

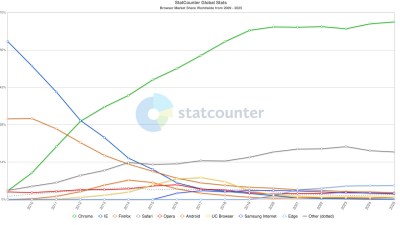

Happily for my own purposes, there are a range of Firefox alternatives which fulfill my browser needs without AI cruft and while allowing me to be a little more at peace with my data security and privacy. There’s Chromium of course even if it’s still way too close to Google for my liking, and there are a host of open-source WebKit and Blink based browsers too numerous to name here.

In the Gecko world that should be an easier jump for a Firefox escapee there are also several choices, for example LibreWolf, and Waterfox. In terms of other browser engines there’s the extremely promising but still early in development Ladybird, and the more mature Servo, which though it is available as a no-frills browser, bills itself as an embedded browser engine. I have not considered some other projects that are either lightweight browser engines, or ones not under significant active development.

Over this summer and autumn then I have tried a huge number of different browsers. Every month or so I build the latest Ladybird and Servo; while I am hugely pleased to see progress they’re both still too buggy for my purposes. Servo is lightning-fast but sometimes likes to get stuck in mobile view, while Ladybird is really showing what it’s going to be but remains for now slow-as-treacle. These are ones to watch, and support.

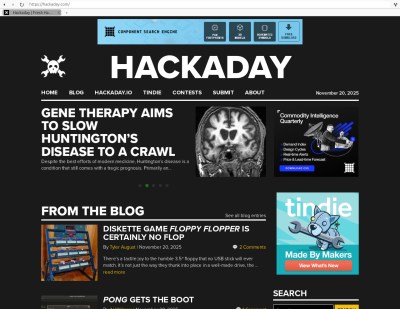

I gave LibreWolf and Waterfox the most attention over the summer, both of which after the experience I’d describe as like Firefox but with mildly annoying bugs. The inability to video conference reliably is a show-stopper in my line of work, and since my eyesight is no longer what it once was I like my browsers to remember when I have zoomed in on a tab. Meanwhile Waterfox on Android is a great mobile browser, right up until it needs to open a link in another app, and fails. I’m used to the quirks of open-source software after 30+ years experimenting with Linux, but when it comes to productivity I can’t let my software disrupt the flow of Hackaday articles.

The Unexpected Choice

It might surprise you after all this open-source enthusiasm then, to see the browser I’ve ended up comfortable with. Vivaldi may be driven by the open-source Blink engine from Chromium and Chrome, but its proprietary front end doesn’t have an open-source licence.

It’s freeware, or free-as-in-beer, and I think the only such software I use. Why, I hear you ask? It’s an effort to produce a browser like Opera used to be in the old days, it’s European which is a significant consideration when it comes to data protection law, and it has (so far) maintained a commitment to privacy while not being evil in the Google motto sense.

It’s quick, I like its interface once the garish coloured default theme has been turned off, and above all, it Just Works. I have my browser back, and I can get on with writing. Should they turn evil I can dump them without a second thought, and hope by then Ladybird has matured enough to suit my needs.

It may not be a trend many of us particularly like, but here in 2025 there’s a sense that the browser has reduced our computers almost to the status of a terminal. It’s thus perhaps the most important piece of software on the device, and in that light I hope you can understand some of the concerns levelled in this series. If you’re reading this from Firefox HQ I’d implore you to follow my advice and go back to what made Firefox so great back in the day, but for the rest of you I’d like to canvass your views on my choice of a worthy replacement. As always, the comments are waiting.