Photographic Revision vs Reality

Last month, one of my PTSD (People Tech Support Duties) requests led me down a deep path related to AI-alterations inside images. It began with a plea to help photograph a minor skin irritation. But this merged with another request concerning automated AI alterations, provenance, and detection. Honestly, it looks like this rush to embrace "AI in everything" is resulting in some really bad manufacturer decisions.

What started with a request to photograph a minor skin rash ended up spiraling into a month-long investigation into how AI quietly rewrites what we see.

This sounds simple enough. Take out the camera, hold out the arm, take a photo, and then upload it to the doctor. Right?

Here's the problem: Her camera kept automatically applying filters to make the picture look better. Visually, the arm clearly had a rash. But through the camera, the picture just showed regular skin. It was like one of those haunted house scenes where the mirror shows something different. The camera wasn't capturing reality.

These days, smart cameras often automatically soften wrinkles and remove skin blemishes -- because who wants a picture of a smiling face with wrinkles and acne? But in this case, she really did want a photo showing the skin blemishes. No matter what she did, her camera wouldn't capture the rash. Keep in mind, to a human seeing it in real life, it was obvious: a red and pink spotted rash over light skin tone. We tried a couple of things:

This irritating experience was just a scratch of a much larger issue that kept recurring over the month. Specifically, how modern cameras' AI processing is quietly rewriting reality.

Following the rash problem, I had multiple customer requests asking whether their pictures were real or AI. Each case concerned the same camera: The new Google Pixel 10. This is the problem that I predicted at the beginning of last month. Specifically, every picture from the new Google Pixel 10 is tagged by Google as being processed by AI. This is not something that can be turned off. Even if you do nothing more than bring up the camera app and take a photo, the picture is tagged with the label:

In other words, this is a composite image. And while it may not be created using a generative AI system ("and/or"), it was definitely combined using some kind of AI-based system.

In industries that are sensitive to fraud, including banking, insurance, know-your-customer (KYC), fact checking, legal evidence, and photojournalism, seeing any kind of media that is explicitly labeled as using AI is an immediate red flag. What's worse is that analysis tools that are designed to detect AI alterations, including my tools and products from other developers, are flagging Pixel 10 photos as being AI. Keep in mind: Google isn't lying -- every image is modified using AI and is properly labeled. The problem is that you can't turn it off.

One picture (that I'm not allowed to share) was part of an insurance claim. If taken at face value, it looked like the person's car had gone from 60-to-zero in 0.5 seconds (but the tree only sustained minor injuries). However, the backstory was suspicious and the photos, from a Google Pixel 10, had inconsistencies. Adding to these problems, the pictures were being flagged as being partially or entirely AI-generated.

We can see this same problem with a sample "original" Pixel 10 image that I previously used.

At FotoForensics, the Error Level Analysis (ELA) permits visualizing compression artifacts. All edges should look similar to other edges, surfaces should look like surfaces, and similar textures should look similar. With this image, we can see a horizontal split in the background, where the upper third of the picture is mostly black, while the lower two thirds shows a dark bluish tinge. The blue is due to a chrominance separation, which is usually associated with alterations. Visually, the background looks the same above and below (it's the same colors above and below), so there should not be a compression difference. The unexpected compression difference denotes an alteration.

The public FotoForensics service has limited analyzers. The commercial version also detects:

In my previous blog entry, I showed that Google labels all photos as AI and that the metadata can be altered without detection. But with these automatic alterations baked into the image, we can no longer distinguish reality from revision.

Were the pictures real? With the car photos (that I cannot include here), my professional opinion was that, ignoring the AI and visual content, the photos were being misrepresented. (But doesn't the Pixel 10 use C2PA and sign every photo? Yes it does, but it doesn't help here because the C2PA signatures don't protect the metadata.) If I ignored the metadata, I'd see the alterations and AI fingerprints, and I'd be hard-pressed to determine if the detected artifacts were human initiated (intentional) or automated (unintentional). This isn't the desired AI promise, where AI generates content that looks like it came from a human. This is the opposite: AI forcing content from a human to look like AI.

My analysis tools rely on deterministic algorithms. (That's why I call the service "FotoForensics" -- "Forensics" as in, evidence suitable for a court of law.) However, there are other online services that use AI to detect AI. Keep in mind, we don't know how well these AI systems were trained, what they actually learned, what biases they have, etc. This evaluation is not a recommendation to use any of these tools.

This inconsistency between different AI-based detection tools is one of the big reasons I don't view any of them as serious analyzers. For the Pixel 10 images, my clients had tried some of these systems and saw conflicting results. For example, using the same "original" Pixel 10 baseline image:

People use AI for lots of tasks these days. This includes helping with research, editing text, or even assisting with diagnostics. However, each of these uses still leaves the human with the final decision about what to accept, reject, or cross-validate. In contrast, the human photographer has no option to reject the AI's alterations to these digital photos.

From medical photos and insurance claims to legal evidence, the line between "photo" and "AI-enhanced composite" has blurred. For fields that rely on authenticity, that's not a minor inconvenience; it's a systemic problem. Until manufacturers return real control to the photographer, sometimes the most reliable camera is the old one in the junk drawer -- like a decade-old Sony camera with no Wi-Fi, no filters, and no agenda.

P.S. Brain Dead Frogs turned this blog entry in a song for an upcoming album. Enjoy!

What started with a request to photograph a minor skin rash ended up spiraling into a month-long investigation into how AI quietly rewrites what we see.

Cameras Causing Minor Irritations

The initial query came from a friend. Her kid had a recurring rash on one arm. These days, doctor visits are cheaper and significantly faster when done online or even asynchronously over email. In this case, the doctor sent a private message over the hospital's online system. He wanted a photo of the rash.This sounds simple enough. Take out the camera, hold out the arm, take a photo, and then upload it to the doctor. Right?

Here's the problem: Her camera kept automatically applying filters to make the picture look better. Visually, the arm clearly had a rash. But through the camera, the picture just showed regular skin. It was like one of those haunted house scenes where the mirror shows something different. The camera wasn't capturing reality.

These days, smart cameras often automatically soften wrinkles and remove skin blemishes -- because who wants a picture of a smiling face with wrinkles and acne? But in this case, she really did want a photo showing the skin blemishes. No matter what she did, her camera wouldn't capture the rash. Keep in mind, to a human seeing it in real life, it was obvious: a red and pink spotted rash over light skin tone. We tried a couple of things:

- Turn off all filters. (There are some hidden menus on both Android and iOS devices that can enable filters.) On the Android, we selected the "Original" filter option. (Some Androids call this "None".) Nope, it was still smoothing the skin and automatically removing the rash.

- Try different orientations. On some devices (both Android and iOS), landscape and portrait modes apply different filters. Nope, the problem was still present.

- Try different lighting. While bright daylight bulbs (4500K) helped a little, the camera was still mitigating most of it.

- Try a different camera. My friend had both an Android phone and an Apple tablet; neither was more than 3 years old. Both were doing similar filterings.

- Use a really old digital camera. We had a 10+ year old Sony camera (not a phone; a real standalone camera). With new batteries, we could photograph the rash.

- On my older iPhone 12 mini, I was able to increase the exposure to force the rash's red tint to stand out. I also needed bright lighting to make this work. While the colors were far from natural, they did allow the doctor to see the rash's pattern and color differential.

- My laptop has a built-in camera that has almost no intelligence. (After peeling off the tape that I used to cover the camera...) We tried a picture and it worked well. Almost any desktop computer's standalone webcam, where all enhancements are expected to be performed by the application, should be able to take an unaltered image.

This irritating experience was just a scratch of a much larger issue that kept recurring over the month. Specifically, how modern cameras' AI processing is quietly rewriting reality.

AI Photos

Since the start of digital photography, nearly all cameras have included some form of algorithmic automation. Normally it is something minor, like auto-focus or auto-contrast. We usually don't think of these as being "AI", but they are definitely a type of AI. However, it wasn't until 2021 when the first camera-enabled devices with smart-erase became available. (The Google Pixel 6, Samsung Galaxy S21, and a few others. Apple didn't introduce its "Clean Up" smart erase feature until 2024.)Following the rash problem, I had multiple customer requests asking whether their pictures were real or AI. Each case concerned the same camera: The new Google Pixel 10. This is the problem that I predicted at the beginning of last month. Specifically, every picture from the new Google Pixel 10 is tagged by Google as being processed by AI. This is not something that can be turned off. Even if you do nothing more than bring up the camera app and take a photo, the picture is tagged with the label:

Digital Source Type: http://cv.iptc.org/newscodes/digitalsourcetype/computationalCaptureAccording to IPTC, this means:

The media is the result of capturing multiple frames from a real-life source using a digital camera or digital recording device, then automatically merging them into a single frame using digital signal processing techniques and/or non-generative AI. Includes High Dynamic Range (HDR) processing common in smartphone camera apps.

In other words, this is a composite image. And while it may not be created using a generative AI system ("and/or"), it was definitely combined using some kind of AI-based system.

In industries that are sensitive to fraud, including banking, insurance, know-your-customer (KYC), fact checking, legal evidence, and photojournalism, seeing any kind of media that is explicitly labeled as using AI is an immediate red flag. What's worse is that analysis tools that are designed to detect AI alterations, including my tools and products from other developers, are flagging Pixel 10 photos as being AI. Keep in mind: Google isn't lying -- every image is modified using AI and is properly labeled. The problem is that you can't turn it off.

One picture (that I'm not allowed to share) was part of an insurance claim. If taken at face value, it looked like the person's car had gone from 60-to-zero in 0.5 seconds (but the tree only sustained minor injuries). However, the backstory was suspicious and the photos, from a Google Pixel 10, had inconsistencies. Adding to these problems, the pictures were being flagged as being partially or entirely AI-generated.

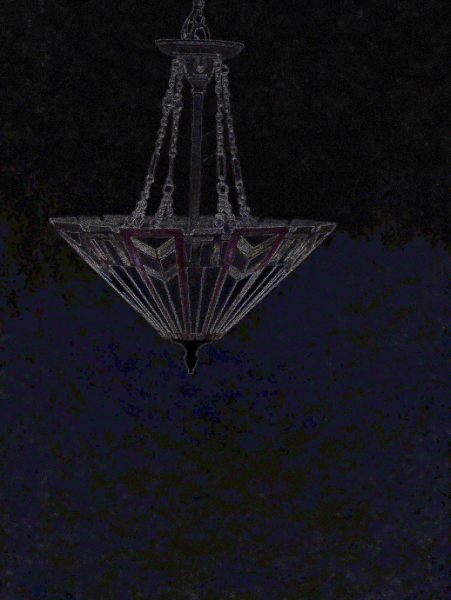

We can see this same problem with a sample "original" Pixel 10 image that I previously used.

At FotoForensics, the Error Level Analysis (ELA) permits visualizing compression artifacts. All edges should look similar to other edges, surfaces should look like surfaces, and similar textures should look similar. With this image, we can see a horizontal split in the background, where the upper third of the picture is mostly black, while the lower two thirds shows a dark bluish tinge. The blue is due to a chrominance separation, which is usually associated with alterations. Visually, the background looks the same above and below (it's the same colors above and below), so there should not be a compression difference. The unexpected compression difference denotes an alteration.

The public FotoForensics service has limited analyzers. The commercial version also detects:

- A halo around the light fixture, indicating that either the background was softened or the chandelier was added or altered. (Or all of the above.)

- The chevrons in the stained glass were digitally altered. (The Pixel 10 boosted the colors.)

- The chandelier has very strong artifacts that are associated with content from deep-learning AI systems.

In my previous blog entry, I showed that Google labels all photos as AI and that the metadata can be altered without detection. But with these automatic alterations baked into the image, we can no longer distinguish reality from revision.

Were the pictures real? With the car photos (that I cannot include here), my professional opinion was that, ignoring the AI and visual content, the photos were being misrepresented. (But doesn't the Pixel 10 use C2PA and sign every photo? Yes it does, but it doesn't help here because the C2PA signatures don't protect the metadata.) If I ignored the metadata, I'd see the alterations and AI fingerprints, and I'd be hard-pressed to determine if the detected artifacts were human initiated (intentional) or automated (unintentional). This isn't the desired AI promise, where AI generates content that looks like it came from a human. This is the opposite: AI forcing content from a human to look like AI.

Other Tools

After examining how these AI-enabled systems alter photos, the next question becomes: how well can our current tools even recognize these changes?My analysis tools rely on deterministic algorithms. (That's why I call the service "FotoForensics" -- "Forensics" as in, evidence suitable for a court of law.) However, there are other online services that use AI to detect AI. Keep in mind, we don't know how well these AI systems were trained, what they actually learned, what biases they have, etc. This evaluation is not a recommendation to use any of these tools.

This inconsistency between different AI-based detection tools is one of the big reasons I don't view any of them as serious analyzers. For the Pixel 10 images, my clients had tried some of these systems and saw conflicting results. For example, using the same "original" Pixel 10 baseline image:

- Hive Moderation trained their system to detect a wide range of specific AI systems. They claim a 0% chance that this Pixel 10 photo contains AI, because it doesn't look like any of the systems they had trained on. Since the Pixel 10 uses a different AI system, they didn't detect it.

- Undetectable AI gives no information about what they detect. They claim this picture is "99% REAL". (Does that mean it's 1% fake?)

- SightEngine decided that it was "3%" AI, with a little generative AI detected.

- Illuminarty determined that it was "14.9%" AI-generated. I don't know if that refers to 14.9% of the image, or if that is the overall confidence level.

- At the other extreme, Was It AI determined that this Google Pixel 10 picture was definitely AI. It concluded: "We are quite confident that this image, or significant part of it, was created by AI."

Fear the Future

Once upon a time, "taking a picture" meant pressing a button and capturing something that looked like reality. Today, it's more like negotiating with an algorithm about what version of reality it's willing to show you. The irony is that the more "intelligent" cameras become, the less their output can be trusted. When even a simple snapshot passes through layers of algorithmic enhancement, metadata rewriting, and AI tagging, the concept of an "original" photo starts to vanish.People use AI for lots of tasks these days. This includes helping with research, editing text, or even assisting with diagnostics. However, each of these uses still leaves the human with the final decision about what to accept, reject, or cross-validate. In contrast, the human photographer has no option to reject the AI's alterations to these digital photos.

From medical photos and insurance claims to legal evidence, the line between "photo" and "AI-enhanced composite" has blurred. For fields that rely on authenticity, that's not a minor inconvenience; it's a systemic problem. Until manufacturers return real control to the photographer, sometimes the most reliable camera is the old one in the junk drawer -- like a decade-old Sony camera with no Wi-Fi, no filters, and no agenda.

P.S. Brain Dead Frogs turned this blog entry in a song for an upcoming album. Enjoy!