Your iPhone Already Has iPhone Fold Software, but Apple Won’t Let You Use It

Picture this: it’s 3 AM, and your message broker is acting up. Queue depths are climbing, consumers are dropping off, and your on-call engineer is frantically restarting pods in a Kubernetes cluster they barely understand. Sound familiar?

For years, we lived this reality with our self-hosted RabbitMQ running on EKS. Sure, we had “complete control” over our messaging infrastructure, but that control came with a hidden cost: becoming accidental RabbitMQ experts, a costly operational distraction from our core mission: accelerating the release of features that directly benefit our customers and help them keep their assets secure.

The breaking point came when we realized our message broker had become a single point of failure—not just technically, but organizationally. Only a handful of people could troubleshoot it, and with a mandatory Kubernetes upgrade looming, we knew it was time for a change.

Enter Amazon MQ: AWS’s managed RabbitMQ service that promised to abstract away the operational headaches.

But here’s the challenge: we couldn’t just flip a switch. We had over 50 services pumping business-critical messages through our queues 24/7. Payment processing, user notifications, data sync—the works. Losing a single message was unacceptable. One wrong move and we’d risk impacting our security platform’s reliability.

This is the story of how we carefully migrated our entire messaging infrastructure while maintaining zero downtime and absolute data integrity. It wasn’t simple, but the process yielded significant lessons in operational maturity.

Running your own RabbitMQ cluster feels empowering at first. You have complete control, can tweak every setting, and it’s “just another container” in your Kubernetes cluster. But that control comes with a price. When RabbitMQ starts acting up, someone on your team needs to know enough about clustering, memory management, and disk usage patterns to fix it. We found ourselves becoming accidental RabbitMQ experts when we really just wanted to send messages between services.

The bus factor was real. Only a handful of people felt comfortable diving into RabbitMQ issues. When those people were on vacation or busy with other projects, incidents would sit longer than they should. Every security patch meant carefully planning downtime windows. Every Kubernetes upgrade meant worrying about how it would affect our message broker. It was technical debt disguised as infrastructure.

The warning signs were there. Staging would occasionally have weird behavior—messages getting stuck, consumers dropping off, memory spikes that didn’t make sense. We’d restart the services and things would go back to normal, but you can only kick the can down the road for so long. When similar issues started appearing in production, even briefly, we knew we were on borrowed time.

Kubernetes doesn’t stand still, and neither should your clusters. But major version upgrades can be nerve-wracking when you have critical infrastructure running on top. The thought of our message broker potentially breaking during a Kubernetes upgrade—taking down half our platform in the process—was the final push we needed to look for alternatives.

With Amazon MQ, someone else worries about keeping RabbitMQ running. AWS handles the clustering, the backups, the failover scenarios you hope never happen but probably will. It’s still RabbitMQ under the hood, but wrapped in the kind of operational expertise that comes from running thousands of message brokers across the globe.

AWS takes care of many of the routine operational tasks, though you still need to plan maintenance windows for major upgrades. The difference is that these are less frequent and more predictable than the constant patching and troubleshooting we dealt with before. The monitoring becomes simpler too—you may still use Grafana panels, but now they pull from CloudWatch instead of requiring Prometheus exporters and custom metrics collection.

Amazon MQ isn’t serverless though, so you still need to choose the right instance size and monitor both CPU, RAM, and disk usage carefully. Since disk space is tied to your instance type, running out of space is still a real concern that requires monitoring and planning. The key difference is that you’re monitoring well-defined resources rather than debugging mysterious cluster behavior.

Security by default is always better than security by choice. Amazon MQ doesn’t give you the option to run insecure connections, which means you can’t accidentally deploy something with plaintext message traffic. It’s one less thing to worry about during security audits and one less way for sensitive data to leak.

When your message broker just works, developers can focus on the business logic that actually matters. You still get Slack alerts when things go wrong and queue configuration is still something you need to think about, but you’re no longer troubleshooting clustering issues or debugging why nodes can’t talk to each other at 2 AM. The platform shifts from something that breaks unexpectedly to something that fails predictably with proper monitoring.

Over 50 services depended on RabbitMQ:

Like many companies that have grown organically, our RabbitMQ usage had evolved into a complex web of dependencies. Fifty-plus services might not sound like a massive number in some contexts, but when each service potentially talks to multiple queues and many services interact with each other through messaging, the dependency graph becomes surprisingly intricate. Services that started simple had grown tentacles reaching into multiple queues. New features had been built on top of existing message flows. What looked like a straightforward “change the connection string” problem on paper turned into a careful choreography of moving pieces.

Messages were business-critical – downtime was not an option.

These weren’t just debug logs or nice-to-have notifications flowing through our queues. Payment processing, user notifications, data synchronization between systems—the kind of stuff that immediately breaks the user experience if it stops working. The pressure was real: migrate everything successfully or risk significant business impact.

Risks included:

Message systems have this nasty property where small problems can cascade quickly. A consumer that falls behind can cause queues to back up. A producer that starts sending to the wrong place can create ghost traffic that’s hard to trace. During a migration, you’re essentially rewiring the nervous system of your platform while it’s still running—there’s no room for “oops, let me try that again.”

We needed a plan to untangle dependencies and migrate traffic safely.

Service Mapping and Analysis

Before touching anything, we needed to understand what we were working with. This meant going through every service, every queue, every exchange, and drawing out the connections. Some were obvious—the email service clearly produces to the email queue. Others were surprising—why was the user service consuming from the analytics queue? Documentation helped, but sometimes the only way to be sure was reading code and checking configurations.

The RabbitMQ management API proved invaluable during this phase. We used it to query all the queues, exchanges, bindings, and connection details—basically everything we needed to get a complete picture of our messaging topology. This automated approach was much more reliable than trying to piece together information from scattered documentation and service configs.

Interactive topology chart showing service dependencies and message flows

With all this data, we created visual representations using go-echarts to generate interactive charts showing message flows and dependencies. We even fed the information to Figma AI to create clean visual maps of all the connections and queue relationships. Having these visual representations made it much easier to spot unexpected dependencies and plan our migration order.

Visual map of RabbitMQ connections and dependencies

The visualizations helped us identify both hotspots where many services converged, and “low hanging fruits”—services that weren’t dependent on many other components. By targeting these first, we could remove nodes from the dependency graph, which gradually un-nested the complexity and unlocked safer migration paths for upstream services. Each successful migration simplified the overall picture and reduced the risk for subsequent moves.

Service Categorization

This categorization became our migration strategy. Consumer-only services were the easiest—we could point them at the new broker without affecting upstream systems. Producer-only services were next—as long as consumers were already moved, producers could follow safely. The Consumer+Producer services were the trickiest and needed special handling.

Migration Roadmap

Having a plan beats winging it every time. We could see which services to migrate first, which ones to save for last, and where the potential problem areas were. It also helped with communication—instead of “we’re migrating RabbitMQ sometime soon,” we could say “we’re starting with the logging services this week, then the notification system the week after.”

Safety Net Strategy

Shovels became a critical part of our strategy from day one. These plugins can copy messages from one queue to another, even across different brokers, which meant we could ensure message continuity during the migration. Instead of trying to coordinate perfect timing between when producers stop sending to the old broker and consumers start reading from the new one, shovels would bridge that gap and guarantee no messages were lost in transit.

Export Configuration

We exported the complete configuration from our old RabbitMQ cluster, including:

RabbitMQ’s export feature became our best friend. Instead of manually recreating dozens of queues and exchanges, we could dump the entire configuration from the old cluster. This wasn’t just about saving time—it was about avoiding the subtle differences that could cause weird bugs later. Queue durability settings, exchange types, binding patterns—all the little details that are easy to get wrong when doing things by hand.

Mirror the Setup

We then imported everything into Amazon MQ to create an identical setup:

The goal was to make the new broker as close to a drop-in replacement as possible. Services shouldn’t need to know they’re talking to a different broker—same queue names, same exchange routing, same user accounts. This consistency was crucial for a smooth migration and made it easier to roll back if something went wrong.

Queue Type Optimization

We made one strategic change: most queues were upgraded to quorum queues for better durability, except for one high-traffic queue where quorum caused performance issues.

Quorum queues are RabbitMQ’s answer to the classic “what happens if the broker crashes mid-message” problem. They’re more durable but use more resources. For most of our queues, the trade-off made sense. But we had one queue that handled hundreds of messages per second, and the overhead of quorum consensus was too much. Sometimes the best technical solution isn’t the right solution for your specific constraints.

Once the new broker was ready, we began moving services live. But we didn’t start with production—we had the same setup mirrored in staging, which became our testing ground. For every service migration, we’d first execute the switch in staging to validate the process, then repeat the same steps in production once we were confident everything worked smoothly.

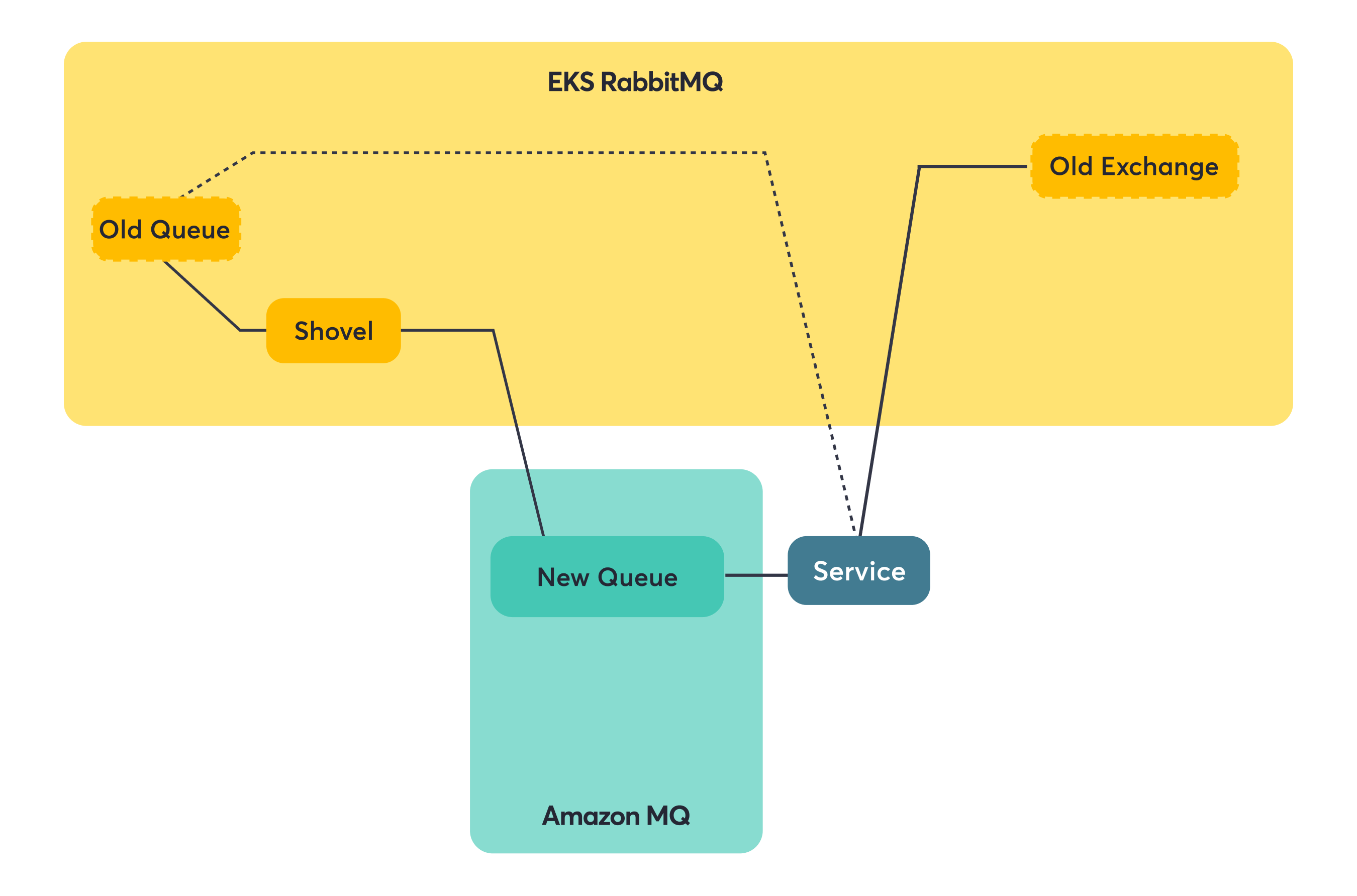

Consumer-only services were our practice round. We could move them over and if something went wrong, the blast radius was limited. The shovel plugin became our safety net—it copies messages from one queue to another, even across different brokers. This meant messages sent to the old queue while we were migrating would still reach consumers on the new broker. No lost messages, no service interruption.

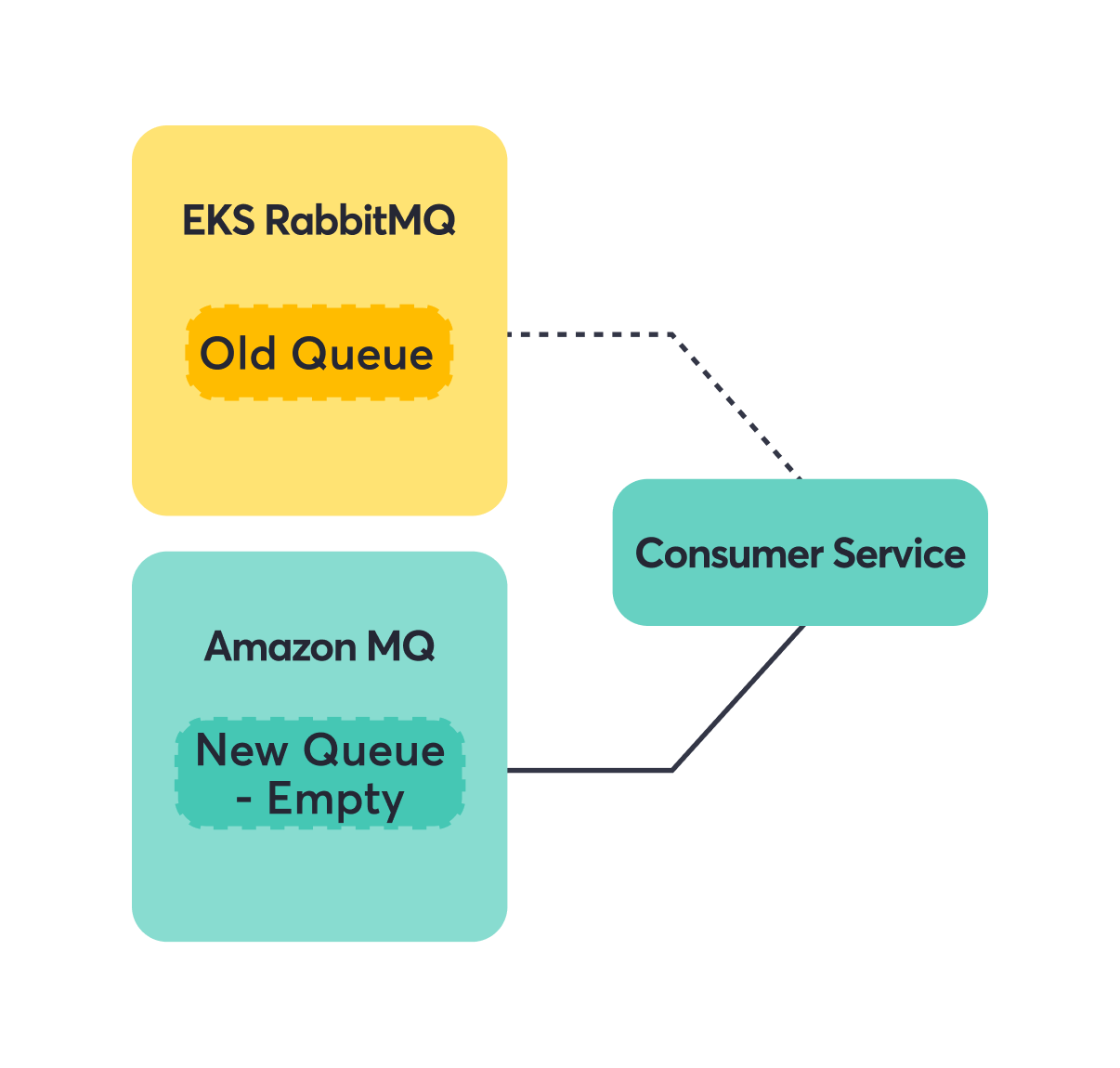

Step 1: Switch consumer to Amazon MQ.

Step 2: Add shovel to forward messages from the EKS RabbitMQ Old Queue to the Amazon MQ New Queue.

Step 3: Consumers seamlessly read from Amazon MQ.

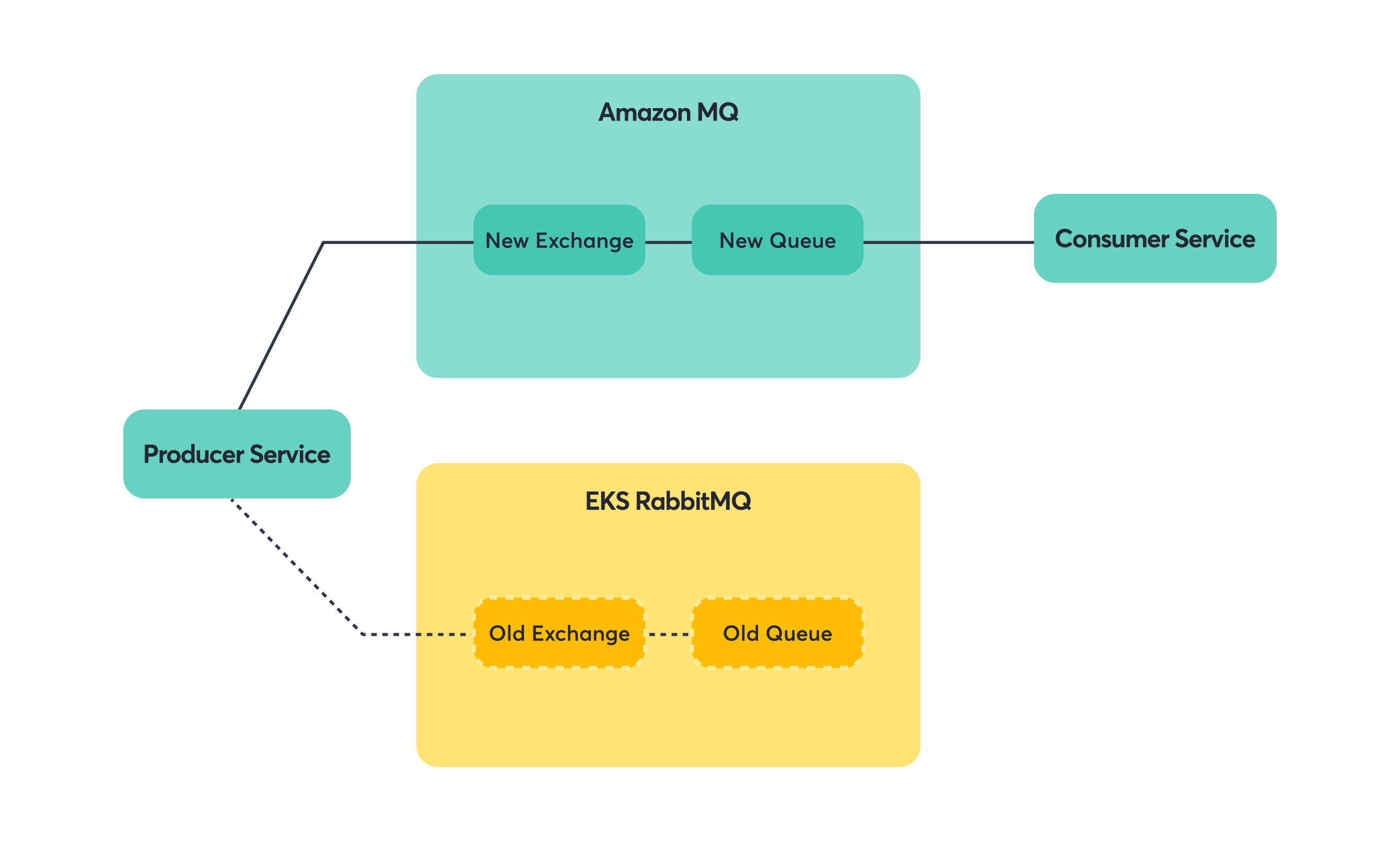

Once consumers were happily reading from Amazon MQ, we could focus on the producers. Since the queue and exchange names were identical, producers just needed a new connection string. Messages would flow into the same logical destinations, just hosted on different infrastructure.

Note: For a producer to be eligible for migration, you want all the downstream consumers to be migrated first.

Step 1: Switch producer to Amazon MQ.

Step 2: Messages flow to the same queues via the new exchange/broker.

Step 3: Remove shovel (cleanup).

Key principle: migrate downstream consumers first, then producers to avoid lost messages.

This principle saved us from a lot of potential headaches. If you move producers first, you risk having messages sent to a new broker that doesn’t have consumers yet. Move consumers first, and you can always use shovels or other mechanisms to ensure messages reach them, regardless of where producers are sending.

These services were the final boss of our migration. They couldn’t be treated as simple consumer-only or producer-only cases because they did both. Switching them all at once meant they’d start consuming from Amazon MQ before all the upstream producers had migrated, potentially missing messages. They’d also start producing to Amazon MQ before all the downstream consumers were ready.

The solution required a bit of code surgery. Instead of one RabbitMQ connection doing everything, these services needed separate connections for consuming and producing. This let us migrate the consumer and producer sides independently.

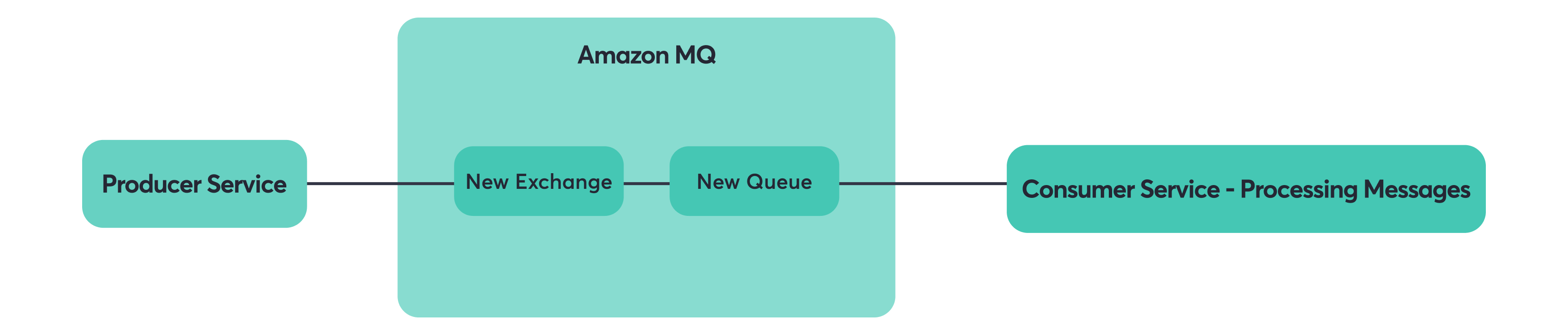

Step 1: Migrate consumer side to Amazon MQ (producer stays on old broker). The service now consumes from the new queue (via the shovel) but still produces to the old exchange.

Step 2: Switch producer side to Amazon MQ (full migration complete). Now both consuming and producing happen on Amazon MQ.

This gave us full control to migrate complex services step by step without downtime.

Old habits die hard, and one of those habits is checking dashboards when something feels off. We rebuilt our monitoring setup for Amazon MQ using Grafana panels that pull from CloudWatch instead of Prometheus. This simplified our metrics collection—no more custom exporters or scraping configurations. The metrics come directly from AWS, and we still get the same visual dashboards we’re used to, just with a cleaner data pipeline.

We focused on four key metrics that give us complete visibility into our message broker:

We set up a layered alerting approach focusing on the infrastructure level and service-specific monitoring:

Live migration is possible, but it’s not trivial and definitely requires careful planning.

We managed to avoid downtime during our migration, but it took some preparation and a lot of small, careful steps. The temptation is always to move fast and get it over with, but with message systems, you really can’t afford to break things. We had a few close calls where our planning saved us from potential issues.

Some approaches that made our migration smoother:

These aren’t revolutionary ideas, but they worked well in practice. The downstream-first approach felt scary at first but ended up reducing risk significantly. Having identical setups meant fewer surprises. Running both brokers in parallel gave us confidence and fallback options.

The migration went better than we expected:

The new system has been more stable, though we still get alerts and have to monitor things carefully. The main difference is that when something goes wrong, it’s usually clearer what the problem is and how to fix it. Less time spent digging through Kubernetes logs trying to figure out why rabbit are unhappy.

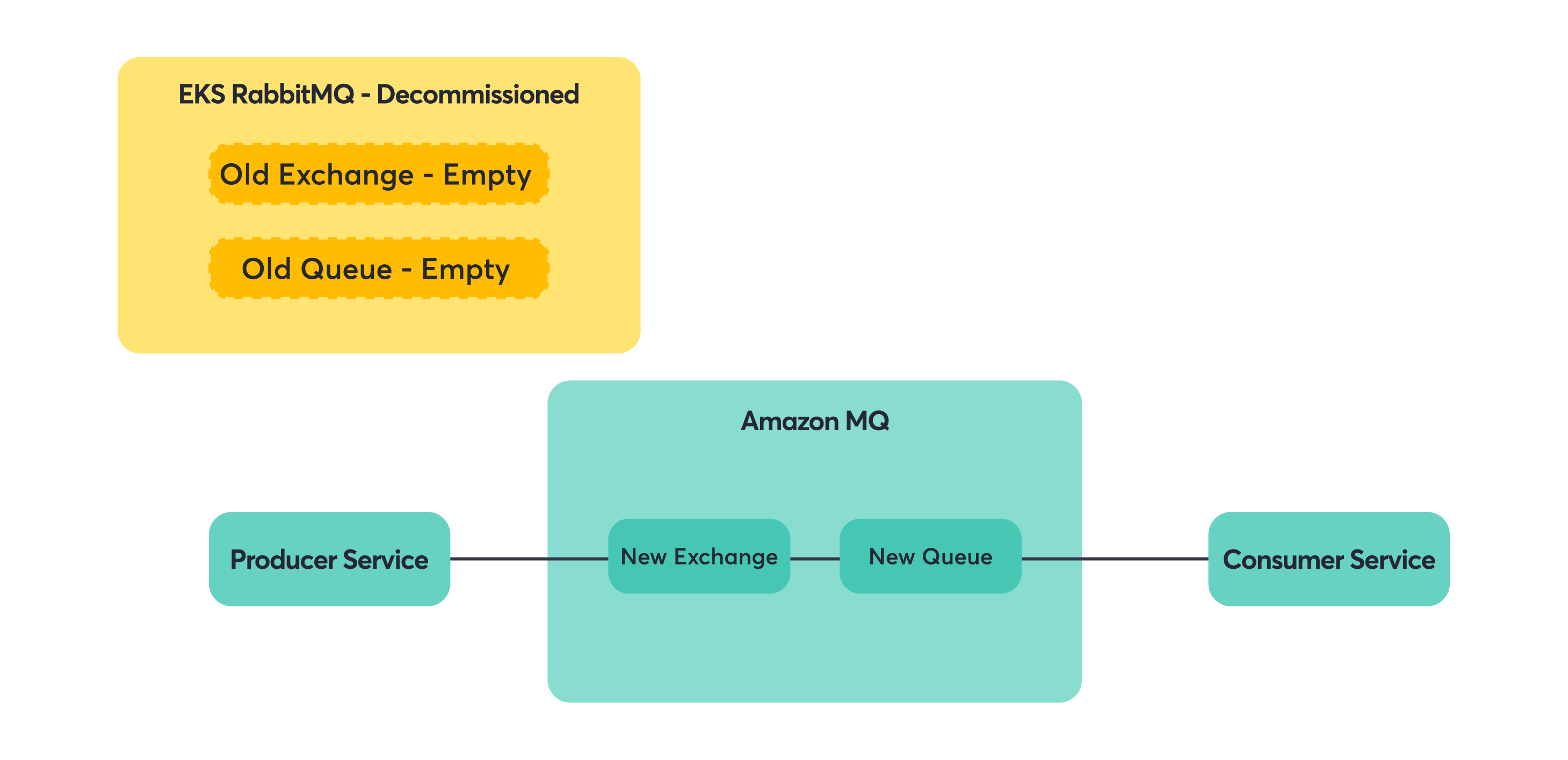

Moving from RabbitMQ on EKS to Amazon MQ turned out to be worth the effort, though it wasn’t a simple flip-the-switch operation.

The main win was reducing the operational burden on our team. We still have to monitor and maintain things, but the day-to-day firefighting around clustering issues and mysterious failures has mostly gone away.

If you’re thinking about a similar migration:

The migration itself was stressful, but the end result has been more time to focus on building features instead of babysitting infrastructure.

Looking back, the hardest part wasn’t the technical complexity—it was building confidence that we wouldn’t break anything important. But with good planning, visual dependency mapping, and a healthy respect for Murphy’s Law, it’s definitely doable.

Now when someone mentions “migrating critical infrastructure with zero downtime,” we don’t immediately think “impossible.” We think “challenging, but we’ve done it before.”

The post Migrating Critical Messaging from Self-Hosted RabbitMQ to Amazon MQ appeared first on Blog Detectify.

At Detectify, we help customers secure their attack surface. To effectively and comprehensively test their assets, we must send a very high volume of requests to their systems, which brings the potential risk of overloading their servers. Naturally, we addressed this challenge to ensure our testing delivers maximum value to our customers while being conducted safely with our rate limiter.

After introducing our engine framework and deep diving inside the tech that monitors our customers’ attack surface, this Under the Hood blog post uncovers an important piece in the puzzle: how our rate limiter service works to make all Detectify scanning safe.

In our previous post, we explained the techniques that we have in place to flatten the curve of security tests that an engine performs on our customers’ systems, avoiding spikes that could overload their servers. As we continuously add more security tests to our research inventory, and with several engines working simultaneously, one can imagine that the combined load from all tests could reach significant levels and potentially create issues for our customers.

To address this, we introduced a global rate limiter designed to limit the maximum number of requests per second directed at any given target. Sensible defaults are in place, and customers have the flexibility to configure this limit based on their needs.

The combined load of engines’ tests towards customers would increase unchecked without a rate limiter

Before jumping into the rate limiter solution, it was important to understand the requirements for our rate limiter.

As a concept, rate limiting is nothing new in software engineering, and there are many tools available for addressing rate limiting challenges. However, we needed to determine if there was anything unique about our situation that would require a custom solution, or if an off-the-shelf product would suffice.

We explored several popular open-source tools and cloud-based solutions. Unfortunately, during our analysis, we could not find any option that fit our criteria. Detectify applies the limit on an origin basis (combination of scheme, hostname and port number), and needs to allow for individual target and highly dynamic configurations. Most existing tools fell short in this area, leading us to the decision to implement our own rate limiter.

Individual target rate limiting configurations, that can change at any time

Rate limiting is a well-known concept in software engineering. Although we built our own, we did not have to start from scratch. We researched various types of rate limiting, including blocking, throttling, and shaping. We also explored the most commonly used algorithms, such as token bucket, leaky bucket, fixed window counter, and sliding window counter, among others. Additionally, we looked into different topologies that we could use.

Our goal was to keep the implementation as straightforward as possible while meeting our requirements. Ultimately, we decided to implement a blocking token bucket rate limiter. Interestingly, given our security testing needs and how “deep in the stack” some security tests are, we landed on a service admission approach rather than the more common proxy approach.

In short, a blocking rate limiter denies requests to a target when the limit is exceeded. In contrast, throttling and shaping rate limiters manage requests by slowing them down, delaying them, or lowering their priority. The token bucket algorithm works by maintaining a “bucket” for each target which gets topped up on a clock with a number of tokens equal to reaching the limit in matter. Each request consumes a token from the bucket in order to be admitted. When the bucket runs out of tokens, the request is denied until the bucket is refilled. The service admission approach means that engines that want to perform a security test towards a target first need to get admission from the global rate limiter, while the proxy approach would work as a more transparent “middleware” for the request between the engine and the target.

Token bucket algorithm

The global rate limiter as an admission service

With the algorithm and topology defined, it was time to explore the technologies that could best meet our needs. The global rate limiter needs to handle a high throughput of requests with a significant level of concurrency, all while operating with very low latency and being scalable.

We further expanded on these requirements and determined that the solution should run in memory and involve as few internal operations as possible. E.g., leveraging atomic operations and simple locks with expiration policies. In the hot concurrency spot, we opted for a single-threaded approach that would run sequentially, avoiding the overhead of concurrency controls.

After discussing our options, we concluded that the best solution was to run the global rate limiter service on long-living ECS tasks backed by a Redis sharded cluster. Since we use AWS, we found it convenient to utilize ElastiCache for creating our Redis sharded cluster.

High-level design of our global rate limiter

The global rate limiter service is rather straightforward, providing a simple API for requesting admission to a target. The more interesting aspect lies in the implementation of the token bucket algorithm between the service and Redis.

We aimed to leverage atomic operations and simple locks with expiration policies, while also running tasks sequentially in the areas of high concurrency. This sequential execution was straightforward with Redis, as it operates in a single-threaded manner. Our focus was to place the concurrency challenges onto it. The simple locks with expiration policies were convenient with Redis, as one of the areas it excels in. At this point, we just had to concentrate on designing the algorithm with as few service-Redis interactions and as atomically as possible. After some iterations, we settled on a solution that runs a Lua script on the Redis server. Redis guarantees the script’s atomic execution, which fits the bill perfectly.

Let’s have a look at the code, with detailed explanations following:

local bucket = KEYS[1] local tokens = ARGV[1] local tokensKey = bucket..":tokens" local lockKey = bucket..":lock" local tokensKeyExpirationSec = 1 local lockKeyExpirationSec = 1 local admitted = 1 local notAdmitted = 0 local refilled = 1 local notRefilled = 0 if redis.call("decr", tokensKey) >= 0 then return { admitted, notRefilled } end if redis.call("set", lockKey, "", "nx", "ex", lockKeyExpirationSec) then redis.call("set", tokensKey, tokens - 1, "ex", tokensKeyExpirationSec) return { admitted, refilled } end return { notAdmitted, notRefilled }

The script takes a few parameters: the bucket name and its limit value for the tokens. As for the time window, we are only working with 1-second time windows. Then, going into checking for admission, the first thing we do is to try and decrement a token from the bucket. If there are available tokens, we admit the request. Otherwise, we check if it’s time for refilling the bucket. To do that, we use Redis’s capability of setting the lock key if it does not exist and provide the 1-second time window as expiration time. If we manage to set the lock key, it means we have entered a new time window and can refill the bucket, which we do while returning the approval to proceed. If we didn’t have enough tokens, and we could not refill the bucket yet, we deny the request. The tokens key also has an expiration time so that we don’t have to do extra cleanups after requests towards a target haven’t happened in a while.

We have been satisfied with the performance since its inception. On average, it handles 20K requests per second, with occasional peaks of up to 40K requests per second. The p99 latency is normally lower than 4 milliseconds, and the error rate nears 0%.

One interesting challenge related to observability is determining how many requests are performed towards a single target. For those familiar with time series databases, using targets as labels would not work, leading to an explosion in cardinality. An alternative could be to rely on logs and build log-based metrics, but if one looks at the volume that we are dealing with, they can imagine it would be extremely costly in financial terms.

To tackle this challenge, we had to think creatively. After some ideation, we decided to log at the moment the buckets get refilled. While this method doesn’t provide the exact number of requests made to a target, it does indicate the maximum number of requests that could be sent to a target at various points in time. This is the essential information for us, as it allows us to monitor and ensure we do not exceed the specified limits.

Keeping our customers secure is about achieving the perfect technical balance to ensure a safe way of running security tests on their attack surfaces without causing unexpected load issues to their servers and potentially affecting their business. The implementation of our global rate limiter allowed us to safely increase the number of engines and security tests in our inventory, running more security testing without breaking their systems.

From an engineering perspective, implementing a global rate limiter presents an interesting technical challenge, and we found a solution that works well for us. If any changes arise, thanks to the extensive ideation throughout the whole process, we are ready to adapt to ensure we provide a safe and reliable experience to our customers. That said, go hack yourself!

Interested in learning more about Detectify? Start a 2-week free trial or talk to our experts.

If you are a Detectify customer already, don’t miss the What’s New page for the latest product updates, improvements, and new security tests.

The post Sending billions of daily requests without breaking things with our rate limiter appeared first on Blog Detectify.