3D Printering: That New Color Printer

Color 3D printing has gone mainstream, and we expect more than one hacker will be unpacking one over the holidays. If you have, say, a color inkjet printer, the process is simple: print. Sure, maybe make sure you tick the “color” box, but that’s about it. However, 3D printers are a bit more complicated.

There are two basic phases to printing color 3D prints. First, you have to find or make a model that has different colors. Even if you don’t make your own models (although you should), you can still color prints in your slicer.

The second task is to set the printer up to deal with those multiple colors. There are several different ways to do this, and each one has its pros and cons. Of course, some of this depends on your slicer, and some depends on your printer. For the purposes of this post, I’ll assume you are using a Slic3r fork like Prusa or OrcaSlicer. Most of the lower-priced printers these days work in roughly the same way.

Current State of Color

In theory, there are plenty of ways to 3D print in color. You can mix hot plastic in the nozzle or use multiple nozzles, each loaded with a different color. But most entry-level color printers use a variation of the same technique. Essentially, they are just like single-nozzle FDM printers, but they have three extra pieces. First, there is a sensor that can tell if filament is in the hot end or not. There’s also a blade above the hot end but below the extruder that can cut the filament off cleanly on command. This usually involves having the hot end ram some actuator that pushes the spring-loaded knife through the filament.

The third piece is some unit to manage moving a bunch of filaments in and out of the hot end. Everyone calls this something else. Bambu calls it an AMS while Flashforge calls it an IFS. Prusa has an MMU. Whatever you call it, it just moves cold filament around: either pushing it into the extruder or pulling it out.

Every filament change starts with cutting the filament below the extruder. That leaves the stringy melted part down in the nozzle. Then the extruder can pull the rest up until the management unit can take over and pull it totally out of the hot end/extruder assembly. That’s why there’s a sensor. It pulls until it sees that the extruder is empty or it times out and throws an error.

Then it is simple enough to move another filament back into the extruder. Of course, the first thing it has to do is push the leftover filament out of the nozzle. Most printers move to a bin and extrude until they are sure the color has changed. However, there are other options.

Even if you push out all the old filament, you may want to print a little waste piece of the new filament before you start printing, and this is called a purge block. Slicers can also push purge material into places like your infill, for example. Some can even print objects with the purge, presumably an object that doesn’t have to look very nice. Depending on your slicer, printer, and workflow, you can opt to print without a purge block, which can work well when you have a part where each layer is a solid color. Some printers will let you skip the discharge step, too, which is often called “poop.”

One caveat, of course, is that all this switching logic takes time and generates waste. A good rule of thumb is to try to print many objects at one time if you are going to switch filament, because the changes are what take time and generate waste. Printing dozens of objects will generate essentially the same amount of waste as printing one. Of course, printing a dozen objects will take longer than a single one, but the biggest part of the time is filament changes, which doesn’t change no matter how many or few you print.

Get Ready to Print

We’ve talked before about creating your own color objects. We’ve even seen how to do it in TinkerCad. Of course, you can also load designs that already have color in them. However, there are several different ways to put color into an otherwise monochrome print.

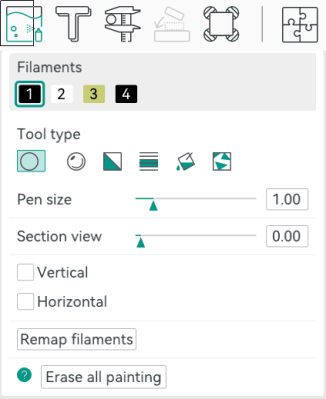

First, you can take a regular print and use your slicer’s paint function to paint areas with different colors. That works, but it is often tedious, and for complex shapes, it is error-prone. Another downside is that you can’t really control the depth easily, so you get strange filament shifts inside the object if you do it that way.

In Orca, you can select an object in the Prepare screen and then use N, or the toolbar, to bring up the paint color dialog. From there, you can pick a brush shape, pen size, and color. Then it is easy to just paint where you like by left-dragging. You can remove paint by pressing Shift while clicking or dragging. Press the little question mark at the bottom left to see other options.

Once you make a color print, the slicer will automatically place a purge block for you unless you turn it off. Assuming you use it, it is a good idea to drag it on the build plate to be closer to the print, which can shave a few minutes of travel time.

From Many, One

Possibly the easiest way, other than not printing in color, of course, is to have each part of the model that needs to be one color as a separate STL file, as we talked about in the previous post. You tell the slicer which part goes with which filament, and you are done.

In Orca, the best way to do this is to import several STL models at one time. The software will ask you: “Load these files as a single object with multiple parts?” If you agree, you get one object made of individual pieces.

In Orca, the best way to do this is to import several STL models at one time. The software will ask you: “Load these files as a single object with multiple parts?” If you agree, you get one object made of individual pieces.

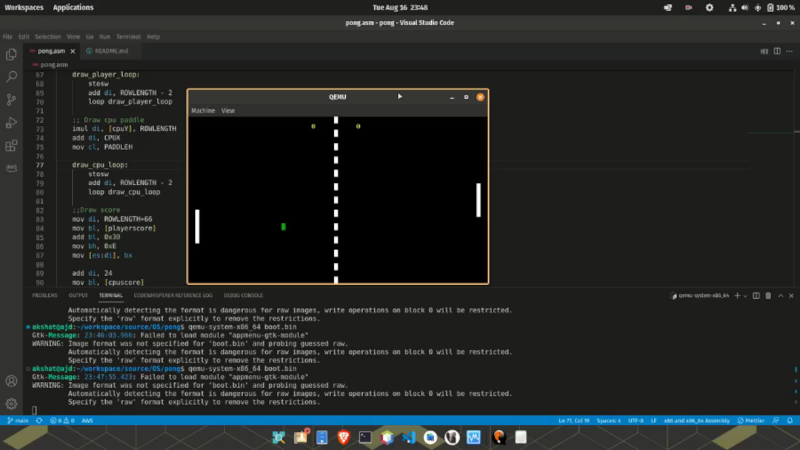

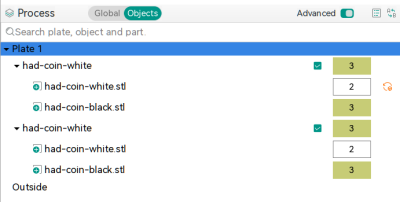

The resulting object won’t look much different until you go to “Process”, on the left-hand side of the screen, and switch from the default Global to Objects. From there, you’ll see the objects and their components. At first, each one will be set to the same color, but by clicking on the color box, you can assign different colors. In the screenshot, you’ll see two identical objects, each with two parts. Each part has a different color. The number is the extruder that holds that color.

There is another way, though. You can avoid almost all of the waste generation and extra time if your model is designed so that each layer is a single color. People have done this for years, where you put a pause in your G-code and then switch filament manually. The idea is the same but the printer can switch for you. For example, the Christmas Tree ornament uses two filament changes to print white, then green, then white again. This works great for lettering and logos and other simple setups where you simply need some contrast.

In Orca, you’ll want to slice your model once and switch to the preview tab. Using the vertical slider on the right-hand side, adjust the view until it shows you where you want the filament change. Then right-click and select “Change Filament.” This is the same way you add a pause if you want to change filament manually, for example.

If you use this method, remember to turn off the purge block. You don’t really need it.

Summary

So now, when you unwrap that shiny new multimaterial printer, you have a plan. Get a color model or color one yourself. Then you can decide if you need color changes or full-blown, and waste-prone, color printing. Either way, have fun!