Discovery Alert: ‘Baby’ Planet Photographed in a Ring around a Star for the First Time!

The (Proto) Planet:

WISPIT 2b

The Discovery:

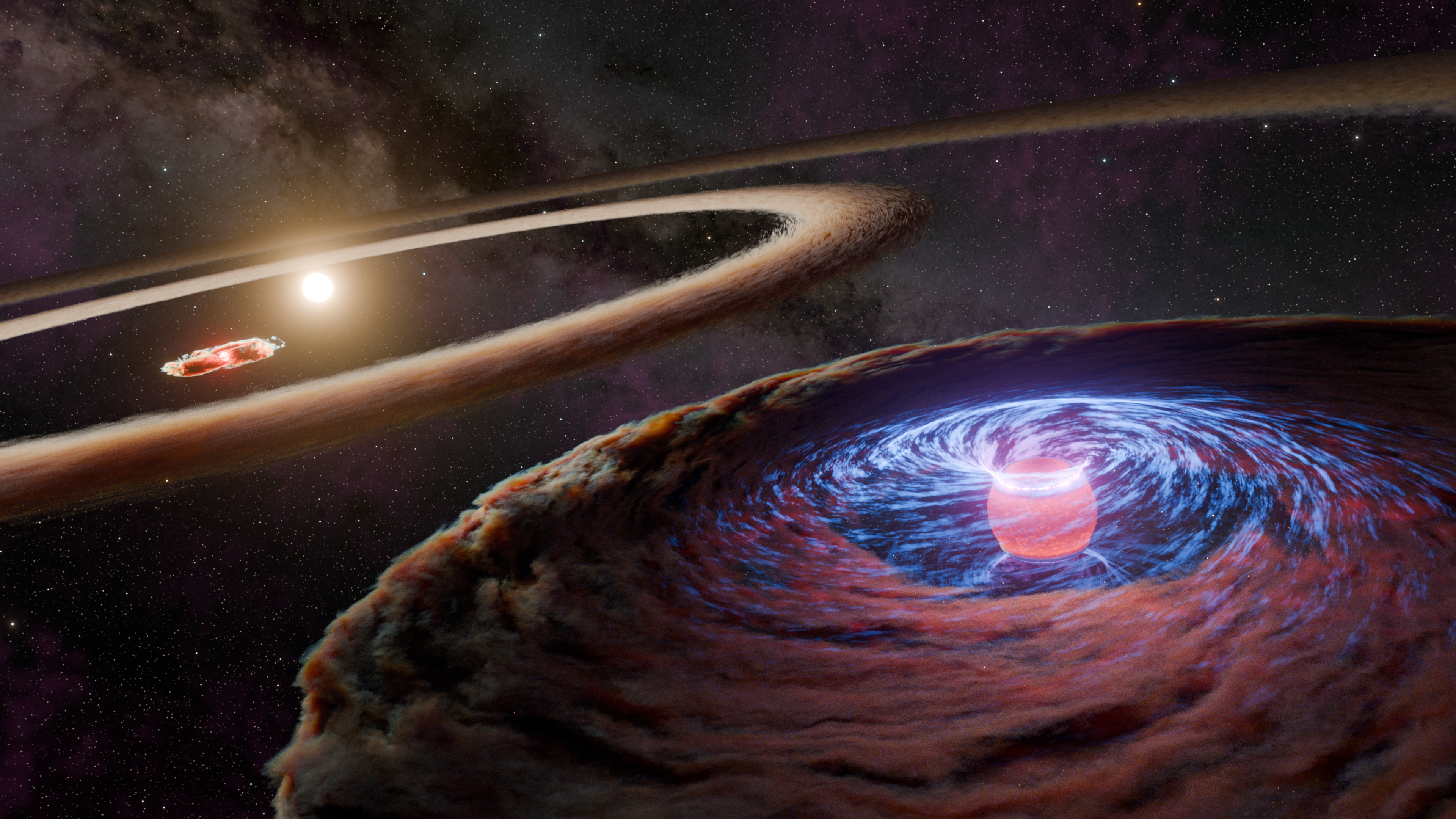

Researchers have discovered a young protoplanet called WISPIT 2b embedded in a ring-shaped gap in a disk encircling a young star. While theorists have thought that planets likely exist in these gaps (and possibly even create them), this is the first time that it has actually been observed.

Key Takeaway:

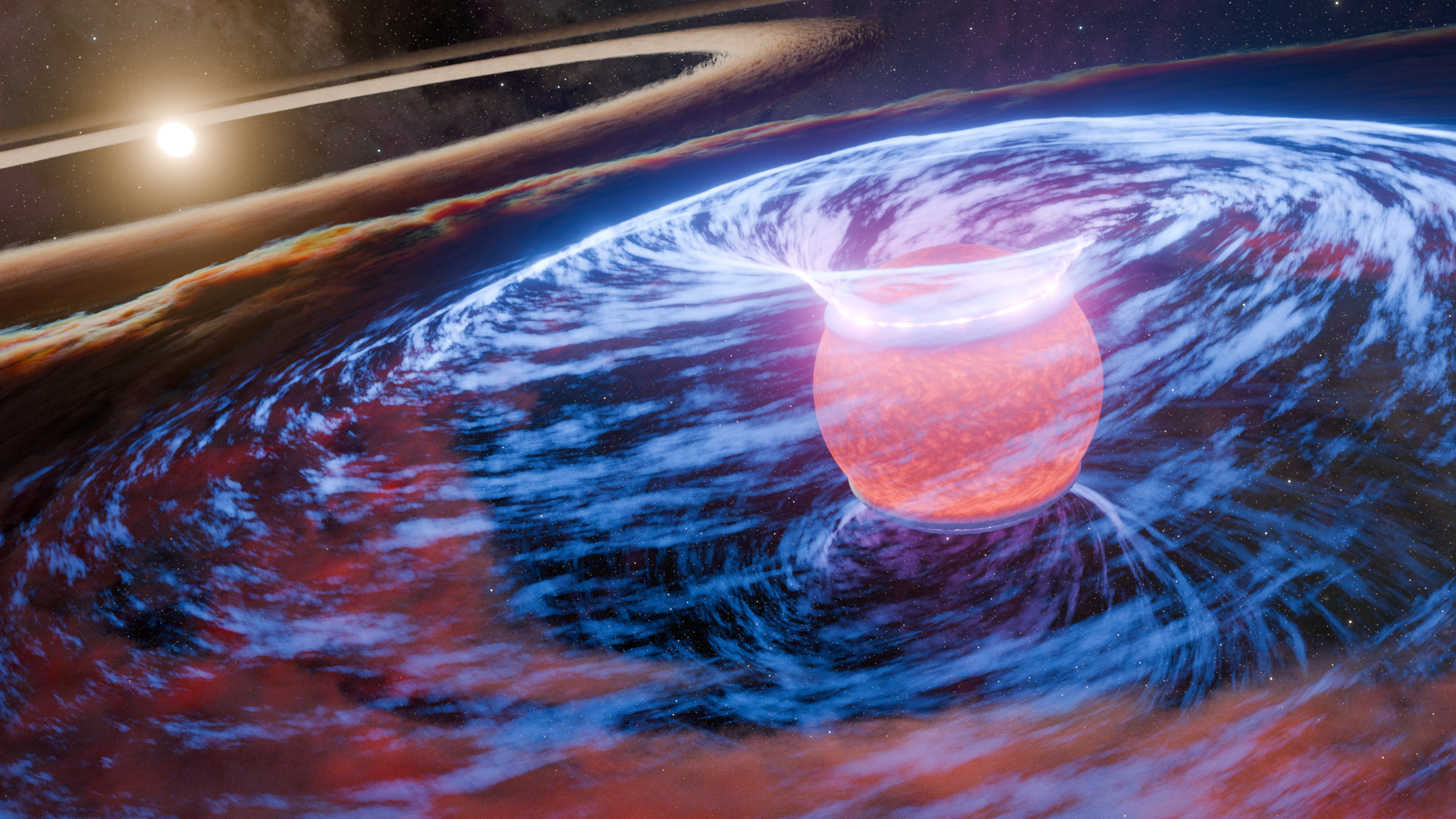

Researchers have directly detected – essentially photographed – a new planet called WISPIT 2b, labeled a protoplanet because it is an astronomical object that is accumulating material and growing into a fully-realized planet. However, even in its “proto” state, WISPIT 2b is a gas giant about 5 times as massive as Jupiter. This massive protoplanet is just about 5 million years old, or almost 1,000 times younger than the Earth, and about 437 light-years from Earth.

Being a giant and still-growing baby planet, WISPIT 2b is interesting to study on its own, but its location in this protoplanetary disk gap is even more fascinating. Protoplanetary disks are made of gas and dust that surround young stars and function as the birthplace for new planets.

Within these disks, gaps or clearings in the dust and gas can form, appearing as empty rings. Scientists have long suggested that these growing planets are likely responsible for clearing the material in these gaps, pushing and scattering dusty disk material outwards and greeting the ring gaps in the first place. Our own solar system was once just a protoplanetary disk, and it’s possible that Jupiter and Saturn may have cleared ring gaps like this in that disk many, many years ago.

But despite continued observation of stars with these kinds of disks, there was never any direct evidence of a growing planet found in one of these ring gaps. That is, until now. As reported in this paper, WISPIT 2b was directly observed in one of the ring gaps around its star, WISPIT 2.

Another interesting aspect of this discovery is that WISPIT 2b appears to have formed where it was found, it didn’t form elsewhere and move into the gap somehow.

Details:

The star WISPIT 2 was first observed using VLT-SPHERE (Very Large Telescope – Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet REsearch), a ground-based telescope in northern Chile operated by the European Southern Observatory. In these observations, the rings and gap around this star were first seen.

Following these observations of the system, researchers looked at WISPIT 2, and spotted the planet WISPIT 2b for the first time, using the University of Arizona’s MagAO-X extreme adaptive optics system, a high-contrast exoplanet imager at the Magellan 2 (Clay) Telescope at Las Campanas Observatory in Chile.

This technology adds another unique layer to this discovery. The MagAO-X instrument captures direct images, so it didn’t just detect WISPIT 2b, it essentially captured a photograph of the protoplanet.

The team used this technology to study the WISPIT 2 system in what is called H-alpha, or Hydrogen-alpha, light. This is a type of visible light that is emitted when hydrogen gas falls from a protoplanetary disk onto young, growing planets. This could look like a ring of super heated plasma circling the planet. This plasma emits the H-alpha light that MagAO-X is specially designed to detect (even if it is a very faint signal compared to the bright star nearby).

When looking at the system in H-alpha light, the team spotted a clear dot in one of the dark ring gaps in the disk around WISPIT 2. This dot? The planet WISPIT 2b.

In addition to observing the protoplanet’s H-alpha emission using MagAO-X, the team also studied the protoplanet in other wavelengths of infrared light using the LMIRcam detector as part of the The Large Binocular Telescope Interferometer instrument on the University of Arizona’s Large Binocular Telescope.

Fun Facts:

In addition to discovering WISPIT 2b, this team spotted a second dot in one of the other dark ring gaps even closer to the star WISPIT 2. This second dot has been identified as another candidate planet that will likely be investigated in future studies of the system.

The Discoverers:

WISPIT-2b was discovered by a team led by University of Arizona astronomer Laird Close and Richelle van Capelleveen, an astronomy graduate student at Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands. This followed the recent discovery of the WISPIT 2 disk and ring system using the VLT, which was led by van Capelleveen.

This discovery was detailed in the paper “Wide Separation Planets in Time (WISPIT): Discovery of a Gap Hα Protoplanet WISPIT 2b with MagAO-X,” published August 26, 2025 in the Astrophysical Journal Letters. A second paper led by van Capelleveen and the University of Galway published on the same day in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

This research was partially supported by a grant from the NASA eXoplanet Research Program. MagAO-X was developed in part by a grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation with support from the Heising-Simons Foundation.