Why LLMs are Less Intelligent than Crows

The basic concept of human intelligence entails self-awareness alongside the ability to reason and apply logic to one’s actions and daily life. Despite the very fuzzy definition of ‘human intelligence‘, and despite many aspects of said human intelligence (HI) also being observed among other animals, like crows and orcas, humans over the ages have always known that their brains are more special than those of other animals.

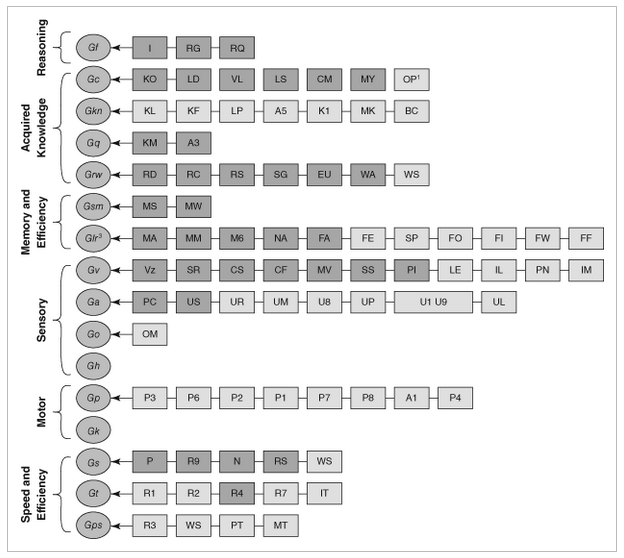

Currently the Cattell-Horn-Carroll (CHC) theory of intelligence is the most widely accepted model, defining distinct types of abilities that range from memory and processing speed to reasoning ability. While admittedly not perfect, it gives us a baseline to work with when we think of the term ‘intelligence’, whether biological or artificial.

This raises the question of how in the context of artificial intelligence (AI) the CHC model translate to the technologies which we see in use today. When can we expect to subject an artificial intelligence entity to an IQ test and have it handily outperform a human on all metrics?

Types Of Intelligence

While the basic CHC model contains ten items, the full model is even more expansive, as can be seen in the graphic below. Most important are the overarching categories and the reasoning for the individual items in them, as detailed in the 2014 paper by Flanagan and McGrew. Of these, reasoning (Gf, for fluid intelligence), acquired knowledge and memory (long and short term) are arguably the most relevant when it comes to ‘general intelligence’.

Fluid intelligence (Gf), or reasoning, entails the ability to discover the nature of the problem or construction, to use a provided context to fill in the subsequent steps, and to handle abstract concepts like mathematics. Crystallized intelligence (Gc) can be condensed to ‘basic skills’ and general knowledge, including the ability to communicate with others using a natural language.

The basic memory abilities pertain to short-term (Gsm) and long-term recall (Glr) abilities, in particular attention span, working memory and the ability to recall long-term memories and associations within these memories.

Beyond these basic types of intelligence and abilities we can see that many more are defined, but these mostly expand on these basic four, such as visual memory (Gv), various visual tasks, speed of memory operations, reaction time, reading and writing skills and various domain specific knowledge abilities. Thus it makes sense to initially limit evaluating both HI and AI within this constrained framework.

Are Humans Intelligent?

It’s generally considered a foregone conclusion that because humans as a species possesses intelligence, ergo facto every human being possesses HI. However, within the CHC model there is a lot of wriggle room to tone down this simplification. A big part of IQ tests is to test these these specific forms of intelligence and skills, after all, creating a mosaic that’s then boringly reduced to a much less meaningful number.

The main discovery over the past decades is that the human brain is far less exceptional than we had assumed. For example crows and their fellow corvids easily keep up with humans in a range of skills and abilities. As far as fluid intelligence is concerned, they clearly display inductive and sequential reasoning, as they can solve puzzles and create tools on the spot. Similarly, corvids regularly display the ability to count and estimate volumes, demonstrating quantitative reasoning. They have regularly demonstrated understanding water volume, density of objects and the relation between these.

In Japanese parks, crows have been spotted manipulating the public faucets for drinking and bathing, adjusting the flow to either a trickle or a strong flow depending on what they want. Corvids score high on the Gf part of the CHC model, though it should be said that the Japanese crow in the article did not turn the faucet back off again, which might just be because they do not care if it keeps running.

When it comes to crystallized intelligence (Gc) and the memory-related Gsm and Glr abilities, corvids score pretty high as well. They have been reported to remember human faces, to learn from other crows by observing them, and are excellent at mimicking the sounds that other birds make. There is evidence that corvids and other avian dinosaur species (‘birds’) are capable of learning to understand human language, and even communicating with humans using these learned words.

The key here is whether the animal understands the meaning of the vocalization and what vocalizing it is meant to achieve when interacting with a human. Both parrots and crows show signs of being able to learn significant vocabularies of hundreds of words and conceivably a basic understanding of their meaning, or at least what they achieve when uttered, especially when it comes to food.

Whether non-human animals are capable of complex human speech remains a highly controversial topic, of course, though we are breathlessly awaiting the day that the first crow looks up at a human and tells the hairless monkey what they really think of them and their species as a whole.

The Bears

Meanwhile there’s a veritable war of intellects going on in US National Parks between humans and bears, involving keeping the latter out of food lockers and trash bins while the humans begin to struggle the moment the bear-proof mechanism requires more than two hand motions. This sometimes escalates to the point where bears are culled when they defeat mechanisms using brute force.

Over the decades bears have learned that human food is easier to obtain and fills much better than all-natural food sources, yet humans are no longer willing to share. The result is an arms race where bears are more than happy to use any means necessary to obtain tasty food. Ergo we can put the Gf, Gc and memory-related scores for bears also at a level that suggests highly capable intellects, with a clear ability to learn, remember, and defeat obstacles through intellect. Sadly, the bear body doesn’t lend itself well to creating and using tools like a corvid can.

Despite the flaws of the CHC model and the weaknesses inherent in the associated IQ test scores, it does provide some rough idea of how these assessed capabilities are distributed across a population, leading to a distinct Bell curve for IQ scores among humans and conceivably for other species if we could test them. Effectively this means that there is likely significant overlap between the less intelligent humans and smarter non-human animals.

Although H. sapiens is undeniably an intelligent species, the reality is that it wasn’t some gods-gifted power, but rather an evolutionary quirk that it shares with many other lifeforms. This does however make it infinitely more likely that we can replicate it with a machine and/or computer system.

Making Machines Intelligent

The conclusion we have thus reached after assessing HI is that if we want to make machines intelligent, they need to acquire at least the Gf, Gc, Gsm and Glr capabilities, and at a level that puts them above that of a human toddler, or a raven if you wish.

Exactly how to do this has been the subject of much research and study the past millennia, with automatons (‘robots’) being one way to pour human intellect into a form that alleviates manual labor. Of course, this is effectively merely on par with creating tools, not an independent form of intelligence. For that we need to make machines capable of learning.

So far this has proved very difficult. What we are capable of so far is to condense existing knowledge that has been annotated by humans into a statistical model, with large language models (LLMs) as the pinnacle of the current AI hype bubble. These are effectively massively scaled up language models following the same basic architecture as those that hobbyists were playing with back in the 1980s on their home computers.

With that knowledge in mind, it’s not so surprising that LLMs do not even really register on the CHC model. In terms of Gf there’s not even a blip of reasoning, especially not inductively, but then you would not expect this from a statistical model.

As far as Gc is concerned, here the fundamental flaw of a statistical model is what it does not know. It cannot know what it doesn’t know, nor does it understand anything about what is stored in the weights of the statistical model. This is because it’s a statistical model that’s just as fixed in its functioning as an industrial robot. Chalk up another hard fail here.

Finally, although the context window of LLMs can be considered to be some kind of short-term memory, it is very limited in its functionality. Immediate recall of a series of elements may work depending on the front-end, but cognitive operations invariably fail, even very basic ones such as adding two numbers. This makes Gsm iffy at best, and more realistically a complete fail.

Finally, Glr should be a lot easier, as LLMs are statistical models that can compress immense amounts of data for easy recall. But this associative memory is an artefact of human annotation of training data, and is fixed at the time of training the model. After that, it does not remember outside of its context window, and its ability to associate text is limited to the previous statistical analysis of which words are most likely to occur in a sequence. This fact alone makes the entire Glr ability set a complete fail as well.

Piecemeal Abilities

Although an LLM is not intelligent by any measure and has no capacity to ever achieve intelligence, as a tool it’s still exceedingly useful. Technologies such as artificial neurons and large language models have enabled feats such as machine vision that can identify objects in a scene with an accuracy depending on the training data, and by training an LLM on very specific data sets the resulting model can be a helpful statistical tool, as it’s a statistical model.

These are all small fragments of what an intelligent creature is capable of, condensed into tool form. Much like hand tools, computers and robots, these are all tools that we humans have crafted to make certain tasks easier or possible. Like a corvid bending some wire into shape to open a lock or timing the dropping of nuts with a traffic light to safely scoop up fresh car-crushed nuts, the only intelligence so far is still found in our biological brains.

All of which may change as soon as we figure out a way to replicate abstract aspects such as reasoning and understanding, but that’s still a whole kettle of theoretical fish at this point in time, and the subject of future articles.

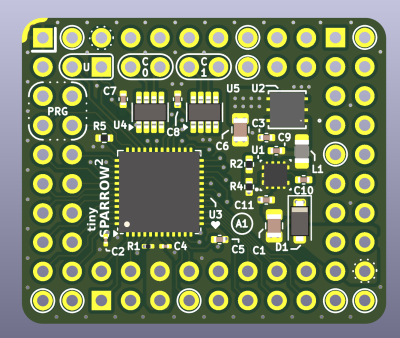

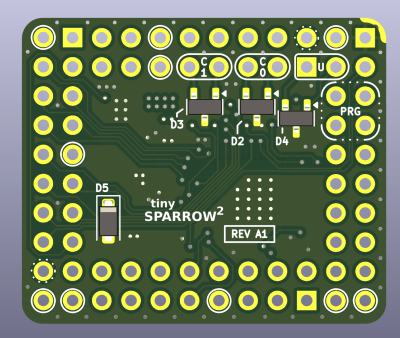

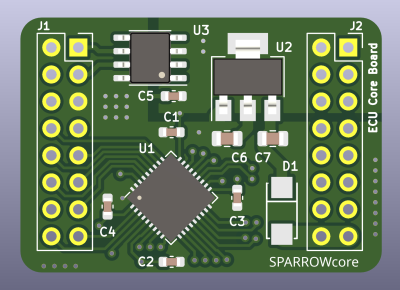

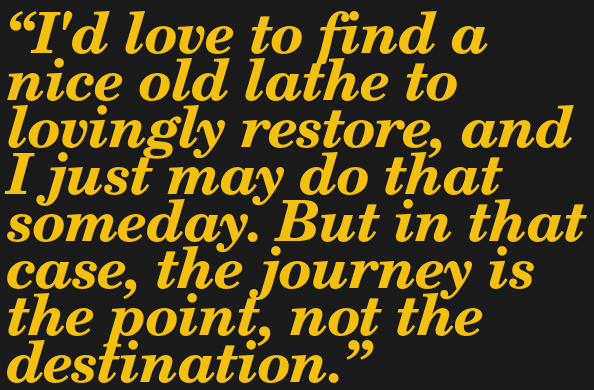

Now, I’m not going to turn this into a printer review — that’s not really the point of this article. What I want to get across is that I decided to buy a solution rather than take on a new hobby. I got the Bambu up and running in about an hour and was cranking out prototype parts for my project later that afternoon. Yes, I might have had the same experience with a returned printer at about half the price of the Bambu, but I felt like the perceived value of a new printer was worth the premium price, at least in this case.

Now, I’m not going to turn this into a printer review — that’s not really the point of this article. What I want to get across is that I decided to buy a solution rather than take on a new hobby. I got the Bambu up and running in about an hour and was cranking out prototype parts for my project later that afternoon. Yes, I might have had the same experience with a returned printer at about half the price of the Bambu, but I felt like the perceived value of a new printer was worth the premium price, at least in this case.